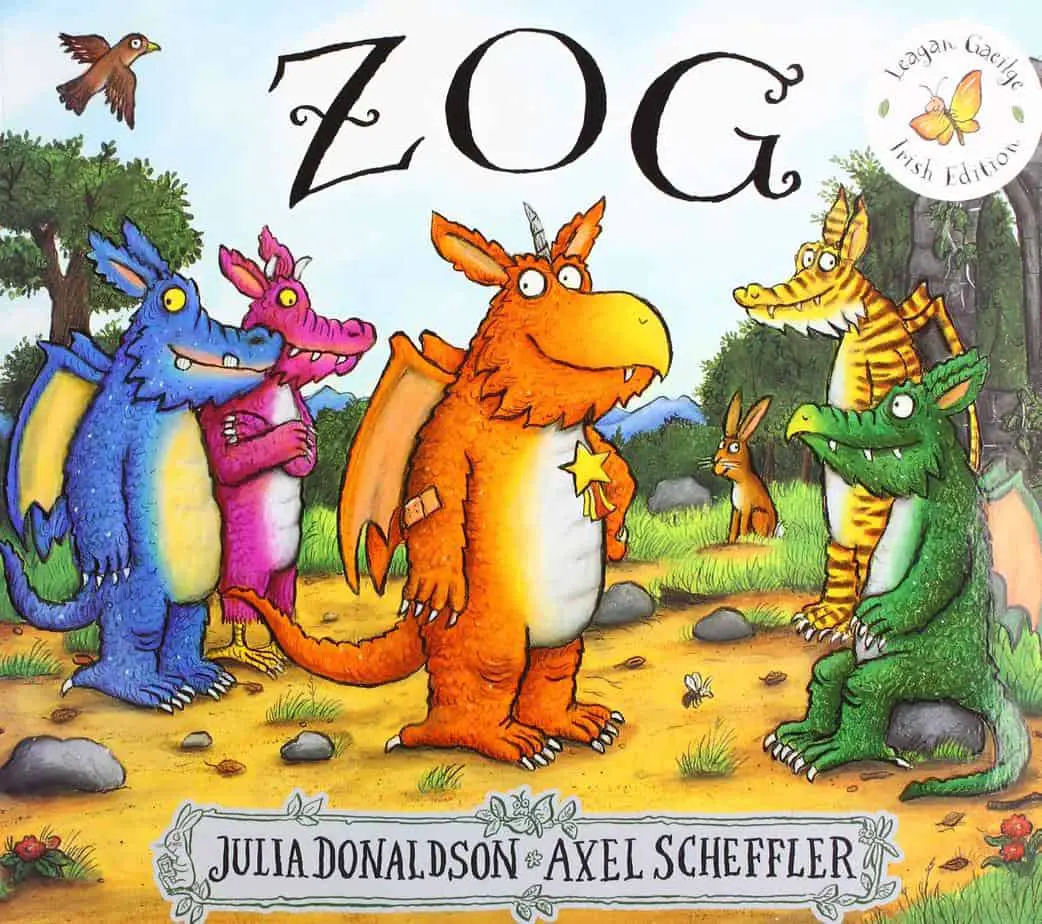

Zog (2010) is a picture book by best-selling British team Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler. Zog is regularly held up as a great feminist story for young readers. Zog interests me as an excellent example of a children’s story which looks feminist at first glance. As I often say: Inversion does not equal subversion. Dig a little deeper, and Zog is pretty far from a feminist text, unless by ‘feminist’ we mean ‘a successful subversion of essentialist masculinity’. It’s something, all right. But let’s raise the bar. A story which challenges prescribed rules about masculinity while simultaneously reinforcing essentialist ideas about femininity cannot count as a successful feminist text.

Pearl is the hero and saviour, but also the more mature and sensible helper. She is a blow-in saviour trope, coming to the rescue whenever masculo-coded Zog injures himself in his stereotypically masculine quest to become a fearsome dragon. The story is a spoof on the classic ‘girl princess saved by a knight from the scary dragon’ story which is why, at first glance, it looks like a feminist triumph. However, a closer look positions the girl character in the same old, same old gendered stereotype of girl as mature little arbitrator (read: pre-mother).

Donaldson has railed against what she calls “books as medicine” – children’s publishing’s tendency towards books with an obvious social message, such as feminism or the climate crisis. “I think now people are doing these terribly message-y books,” Donaldson told me. “I’m just as feminist as anyone else, but you know there are now lots of books to show that girls can be feisty.” She balks at the idea of picture books as activism. “Even if its message was something I really care about, like saving the planet, I probably wouldn’t do it unless I had a really juicy idea.”

The Guardian

SETTING OF ZOG

This is a fairytale world with influences from the contemporary real world: The dragons attend school and are taught how to breathe fire and steal princesses. (This is not a wild and innate tendency.)

STORY STRUCTURE OF ZOG

PARATEXT

Marketing copy of the story tell us that Zog is the main character. (The book is also named after Zog.) Below is a description from a book recommending feminist texts for children aged 0-14 in an appendix:

Zog is an accident prone dragon failing in his training but he gets by with help from a mysterious girl. When he has to take on the hardest task at Dragon School — capturing a princess — she’s on hand to save the day again.

The Gender Agenda: A First-Hand Account of How Girls and Boys Are Treated Differently by James Millar and Ros Ball

Even in their own summary of this feminist recommendation, the authors of The Gender Agenda don’t position the girl as the star of the story.

SHORTCOMING

So, who is the main character? This is one of those stories which uses gender inversion (This is really about the girl, not the boy!) as ‘the surprise’ at the end, shifting from a story about a boy dragon whose job is to rescue a princess, to a story about a girl who starts a minor cultural renovation.

Because the story is mostly not about Pearl, we never learn much about her, other than that she is a human-looking character who spends a lot of time wandering around wooded areas. Like the cranky dwarf in Snow White and Rose Red, she’s always there. (Maybe the woods are very small?)

I code her as a young, relatable witch archetype — relatable because she looks just like a human girl. One subcategory of witch is the healer witch. Pearl is clearly one of those, with her sticky-plasters, peppermints, bandages and consolatory words at the ready. She is able to magically fix Zog completely whenever he falls. After this she offers him her entire self, with the dragon’s goals to become a proper dragon as the main end. Of course, this isn’t the end of the story. But I’d like readers to think carefully about whether the ideology of Girls As Martyr Carers is actually subverted.

The witch healer archetype is common in feminist stories, based on the idea that before medicine was masculinised, female healers and midwives were respected members of their communities.

But we shouldn’t take this at face value.

The healer-witch archetype has been co-opted by some feminists, but Diane Purkiss critiques the archetype as ultimately unhelpful to feminism

The roles of the herbalist-midwife-witch are traditional feminine roles: nursing, healing, caring for women and children. They are roles which centre on domestic space and activity, especially activities derived from women’s traditional roles as homemakers, such as the provision of herbal remedies, flower-gardening and so forth. Many of these skills are represented as either innate or matrilineally inherited, as ‘natural’ rather than learned. The villagers say Starhawk’s witch has healing hands. These figurations of innate power essentials the witch’s art, so that healing and midwifery are presented as innately feminine skills. This subtends the notion that these qualities are somehow natural to women, especially since healer-witches are never men.

Diane Purkiss, The Witch in History: Early modern and twentieth-century representations

The essentialist view that women are innately good at helping and healing does nothing for women, and nothing for men who wish to enter the caring professions. In Zog, the Dragon School is comically relatable, and suggests that there’s nothing innate about breathing fire and stealing princesses. Donaldson successfully subverts the idea of masculine ‘fieriness’ (read: violence) and control over women. There’s no such subversion with Pearl’s storyline. We don’t know who taught Pearl to administer nursing and caring services; we conclude (wholly subconsciously, of course) that she is naturally like that.

DESIRE

Zog has the desire line, and tries to win golden stars for being good at Dragon School. He doesn’t realise he’s stuck in this restrictive system in which he is required to breathe fire and steal princesses. (We will learn this is not what he wanted to do at all.)

OPPONENT

Zog’s teacher (Madam Dragon) is Zog’s opponent. She is indocrinating her dragons into a stereotypically dragon-like life, with no thought to individual preference. When Zog breaks free of this role as fire-breathing, aggressive dragon, Donaldson successfully subverts a problematic form of masculinity.

We might say Madam Dragon is the ‘secret’ opposition. It’s a bit too subtle to function as opposition in a story for young readers. Donaldson knows this, and her on-the-page opposition is far more clear. (Any story about a knight, a princess and a dragon requires an on-the-page battle.) A knight and a dragon will end up fighting over a princess.

PLAN

Driven by the opponent/teacher, Zog is required to do dragon-y things he’s not good at. He ends up injuring himself, which leads to Pearl showing up and helping him out. We’ll learn eventually that Pearl wishes to be a doctor, so she’s probably practising on injured passersby.

Meanwhile, the knight is planning to steal/woo the beautiful princess.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Eventually there’s a showdown when worlds collide, bringing all characters together. A knight and Zog the Dragon are fighting over the princess in the tall castle. (This is all masterful plotting and storytelling, by the way.)

Princess Pearl stands between the dragon and the knight, breaking up their fight. This is staged as a female character between two warring male characters, telling them off for fighting. Not only are girls good little nurses (to male characters) but they’re also useful when it comes to breaking up fights (between male characters). Pearl is once again positioned as the ‘good little mother’. She is so perfect as a character there is no space for Pearl’s character arc. Ergo, Pearl is not the star of the story.

Sometimes when evaluating the feminism of a text, it can be useful to start with how often a female character gets to speak. But we can’t leave it at that. After all, Pearl gets her own monologue.

Part of me wonders if I’m being too hard on this story. There’s nothing wrong with spending your days wandering around the woods looking for people to care for, right? We need more of those people, not fewer. Another feminist stance looks like this: Why does feminism tend encourage girls becoming more like boys rather than the other way round? Can’t Pearl’s caring nature stand in as a positive form of femininity which boys can then be encouraged to emulate?

I wondered that, and the story could have led young readers in that direction. Then I got to Pearl’s monologue and understood the storytellers have no intention of conveying that particular form of feminist ideal. Pearl tells us she wants to ‘be a doctor and travel here and there’. More than half of family doctors are women these days, and may no longer be coded traditionally masculine by young readers, but the highly qualified professional who must leave home to do good work fits the 3000 year old masculine mythic structure, and is a traditionally masculine ending for this feminine character.

For those inclined to argue there’s nothing inherently masculine about leaving Home to ride a dragon as a flying doctor, we are soon offered unambiguous insight into how the storytellers feel about femme-coded activities which involve staying at Home and performing caregiving duties as unpaid but nonetheless invaluable members of their own tribes: Pearl doesn’t want to be a princess, ‘prancing around in a silly, frilly dress‘.

Clearly, clearly, these storytellers don’t believe ‘doctor’ concords with ‘femininity’ at all, otherwise they might show Pearl — or the captured princess — performing her doctor’s duties in a pretty dress. The dress itself isn’t just a dress. The dress stands metonymically for femininity. There’s nothing in this story to reassure the girl reader that it’s possible to become a doctor and enjoy feminine fripperies at once; it seems one must choose. The plot creates another false binary, when the storytellers seem to want to smash binary notions of gender.

ANAGNORISIS

When Pearl reveals that she doesn’t want to be a princess, she wants to be a doctor, Zog and the knight realise that’s what they want from life, too. Note that it is two masculo-coded characters who enjoy the self-revelation — it appears Pearl has been working towards her goal for quite some time. This remains Zog’s story. (The star of a story is the character who changes the most, as in, has the biggest self-revelation.)

Don’t mistake ‘change of plan’ for ‘change in character’. At first glance Pearl appears to change because her nursing skills have led her to the conclusion that she’d make a good doctor. I would argue she’s been working to this end her whole life. Pearl started the story as a caring, mature character and ended exactly the same way. The knight was an archetypal warrior who learned to care only after ‘the little mother’s’ speech. Zog’s was a coming-of-age story.

Zog is therefore an excellent case study of how inversion does not equal subversion . This picture book appears at first glance to challenge gender stereotyping, but (re)establishes girls as caring, mature (good little mothers) and natural arbitrators in the concerns of males, who are central.

NEW SITUATION

Pearl, the knight and the dragon fly off to perform their work as Flying Doctors.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Pearl is clearly the driver of all this change, in the way Merida is the driver of Brave.

In both Zog and in Brave, a driven, aspirational girl starts a mini-revolution within her own society. In both stories, that revolution is a shift against typical gender-stereotyping. The intent of both stories is noble, but both Brave and Zog demonstrate just how difficult it is, to subvert problematic ideologies, without inserting extra problems — as unintended consequences, I’m sure.

In Brave, Merida tries to push against the gender stereotypes and is punished for it. That’s the main problem there, if the writers were hoping to persuade girl audiences to challenge the status quo without fear.

In Zog, girl readers will be left with the impression that girls are naturally good little nurses and helpers, buried within yet another plot about the travails of boys. Boys can also see that when they hurt themselves or need some tender loving care, a girl will be there (or should be there) at the ready. There is absolutely nothing subversive about that.

Zog is good for extending life-options for boys; not actually that great for girls.

RESONANCE

As mentioned above, Zog now makes it onto lists of Feminist Stories For Children. Being a best-seller in England, Zog will probably be a regular on these lists for decades to come, alongside Roald Dahl’s Matilda. Zog has been adapted as a short animated film, finding an even wider audience.

Zog evinces a ‘feminist’ plot that’s not all that unusual: A story is mainly about a boy, and a girl who cares for him, then right at the end the girl steps in to rescue everyone. Another picture book example is Samson: the Mighty Flea! by Angela McAllister and Nathan Reed.

For more on that, see Subversion and Storytelling: How Is It Done?