“You’re Ugly, Too” is a short story by American writer Lorrie Moore, first published in a 1989 edition of The New Yorker — Moore’s first for the New Yorker. Find it also in her short story collection Like Life (1990).

New Yorker editors pointed out to Moore several “vulgarities” of the writing process she had committed in the story. “All through the editing process, they said, ‘Oooh, we’re breaking so many rules with this.’“

Encyclopedia.com

Why did the crew at The New Yorker feel Lorrie Moore’s short story — the first of hers they’d seen/discussed seriously — broke the ‘rules’ of writing? What rules were they talking about.

I wasn’t there and can’t tell you for sure, but I’d like to consider this question.

- Zoë is a woman, but she’s not “likeable”. She’s not even likeably unlikeable. (At least, she’s not written that way, panding to readers’ desire to like their main characters).

- Zoë’s actions never fully make sense to the reader, even after re-reading. Her actions at the party, like her sense of humour, are absurd.

- Zoë is nihilist and therefore passive. A difficult character to write.

SETTING OF YOU’RE UGLY, TOO

Basically, an unmarried Midwestern history professor flies to Manhattan to spend Halloween weekend with her younger sister. It’s the mid-to-late 1980s. She is originally from Maryland, New England, and came to Illinois via another college, in Minnesota.

Some have said that the main character of “You’re Ugly, Too” is teaching in a thinly disguised Wisconsin, perhaps influenced by the fact that the author, too, taught in such a place.

The mid 1980s were an interesting time for feminism. (Isn’t it always an interesting time for feminism?) Women in academic jobs were still the token additions, and made to feel like it, via what we’d now called microaggressions.

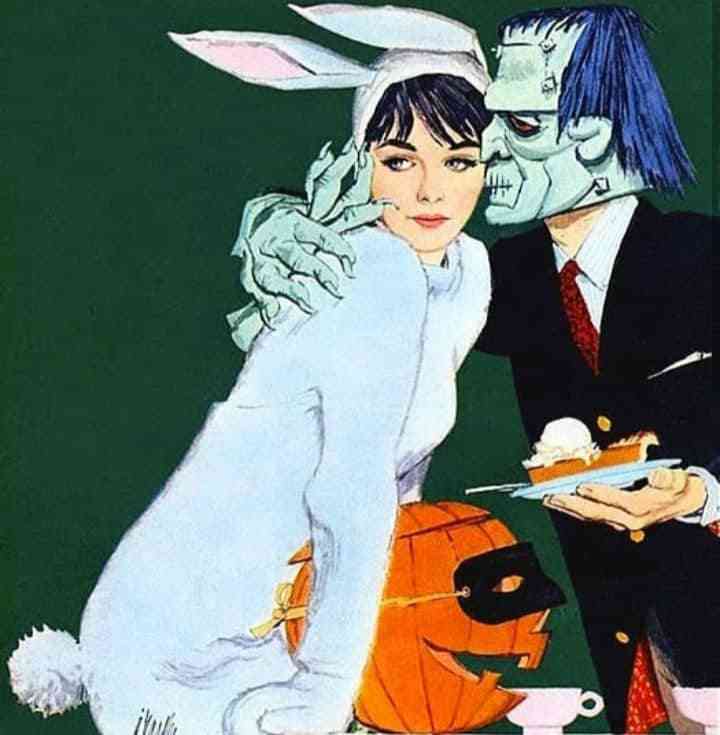

So when Zoë returns to her sister and meets a man at a Halloween party dressed in a grotesque exaggeration of a woman’s body, I’m not altogether surprised that she responds to him negatively. Black face is out of fashion. Yet it’s still okay to dress up in a comically femme body. (I am not including trans women in this particular form of grotesquerie; I most certainly am not.)

Parties are useful in fiction because characters in conflict are thrown together.

NARRATION OF YOU’RE UGLY, TOO

The focal character is Zoë, and the story is told by a third person narrator on the consonant end of the spectrum. Meaning: The voice of the narrator is basically Zoë’s own mordant, sardonic and sarcastic voice. The sense of humour conveyed by the narrator matches exactly the sense of humour conveyed via Zoë’s dialogue. Consonant and Dissonant narration are terms Dorrit Cohn came up with. Cohn actually invented them to describe ‘psycho narration’, which has been superseded by ‘close third person’ in modern storytelling, but I still think there’s a continuum within the ‘close’ part of close third person. Sometimes the ‘camera’ is right inside a character’s head; other times hovering behind, or just above.

CONSONANT NARRATION: The narrator remains close to the consciousness they narrate. Also known as figural (figurative) narration. The narrator is effaced (basically invisible). The reader can’t easily tell the difference between the narrator’s voice and the consciousness of the character being described. We learn nothing about the consonant narrator’s position/opinions because they’re barely visible. We get no impression of them as a separate character.

Psycho Narration

The narration of a story affects its content. (The medium is the message.)

Consonant narrators concentrate on showing rather than telling, like the cinema verite documentary makers who avoid showing their own faces on screen, or making use of voiceover. “I’ve shown you what’s happening — now make up your own mind.”

I’m paraphrasing here, but critics such as John E. Aldridge have said of Lorrie Moore that she is excellent at character sketches but writes her characters as if they exist ‘totally apart from society’.

Writers are often told: Character is an outworking of setting. Characters are shaped by their story worlds/milieu. Unless we make a clear link between character and setting, we fail to ‘give meaningful relevance to a general human condition or dilemma’. (I’m still using Aldridge’s words here.)

Perhaps Lorrie’s choice of narration, sans the editorial asides, creates this uneasy feeling for the reader, who never really knows Zoë completely. Perhaps this is why some readers feel she is not an outworking of her setting, at least not in the way we have come to expect in modern depictions of fictional characters.

STORY STRUCTURE OF YOU’RE UGLY, TOO

“You’re Ugly, Too” is a much more character-driven story than it is a plot-driven one.

Encyclopedia.com

“You’re Ugly, Too” is basically a character study. The earnest Midwestern setting (and its people) serves as ironic counterpoint to the sarcastic vibe emitted by Zoë, who feels she is very much Not From There.

There’s a lot of seamless time travelling. No one can write dialogue blocks like Lorrie Moore can write dialogue blocks, with a conversation starting on one page, then picking up again after a big chunk of backstory, with the reader reintroduced perfectly back into the conversation, knowing exactly who’s speaking and what they were talking about before the long diversion.

PARATEXT

“You’re Ugly, Too” tells the story of Zoë Hendricks, an unmarried history professor who lives alone in the small Midwestern town of Paris, Illinois, and teaches in the local liberal arts college; the story examines her relationships with men, her students, her sister and, in general, her life. With a sparse plot, Moore’s story relies on Hendricks’s character and the running gags and jokes she relentlessly throws at anyone within listening distance to sustain it.

Encyclopedia.com

SHORTCOMING

Zoë’S LIKEABILITY SCORE

Femme-coded people must work harder before being considered ‘likeable’ and this applies equally to femme-coded characters in fiction. Zoë is not written to be a likeable character in the way the heroine of a romance novel is written to be a likeable character. However, certain readers are going to like her. She’s probably pretty divisive, and reminds me of Lorelai Gilmore. (Fans love Lorelai; another large portion of a potential audience won’t watch more than a quarter episode.) Whether readers like her or not will depend on:

- Whether we think she’s perceptive. ‘Prickly’ characters can work very effectively in stories, sometimes because they say what we all would like to say, and what we sometimes suggest we did say when recounting (and embellishing) a frustrating social interaction to allies afterwards. Doc Martin is one example of a satisfying prickly character. Zoë is a little different because I can’t imagine many of us would imagine saying the absurd things she comes out with. She loses me when she says, “Tell me, Earl. Does the word fag mean anything to you?” (To right-minded people, that word was as offensive in the mid 1980s as it is today.)

- Sometimes we don’t so much ‘like’ a character as admire them. Is Zoë admirable? She doesn’t seem competent. She’s doing an increasingly poor job as history professor. She’s not even connecting with her students let alone teaching them anything useful. On the other hand, Zoë’s sardonic take on the world is somewhat adaptive: She pacifies herself on plane rides by telling herself there’s nothing much to live for anyway, which is one way of coping with life.

- Whether we think she’s relatable. I do find Zoë somewhat relatable, though Moore has taken that relatability and stretched it beyond my powers of empathy. Zoë takes a year of heavy revising before submitting an academic paper, and I can identify with ‘publishing anxiety’. (I think many people can, and we’re all publishers now due to social media.)

- Whether we understand how she came to be. Moore gives us some backstory about Zoë and Evan’s childhood speech difficulties. I’m no longer believing everything Zoë tells Earl by the point in the party conversation but Zoë tells Earl that her sense of humour is defensive, and a way of adapting to her speech issues as a kid. She knows certain one-liners and is able to practise those, and so one-liners became her thing. (I’m not sure this is how it really works?)

- Whether we think she is funny

Is Zoë ironic or is she sarcastic?

Irony: A meaningful gap between expectation and outcome. The natural world contains plenty of irony. Humans don’t have to manufacture any, though sometimes choose to, to make a certain point.

Sarcasm: A mode of communication in which the speaker says something other than what they mean, expecting the other person to know they don’t mean that at all. (When this kind of sarcasm makes statements about race/gender/disability this mode of sarcasm is known as ‘hipster irony’, further confusing the distinction between ‘irony’ and ‘sarcasm’.

People who make use of sarcastic modes of communication are often thought to be using it unkindly. What about Zoë? Is she an unkind person?

Lorrie Moore’s dialogue is wonderfully multi-layered, and open to many reader responses. When someone asks Zoë “What is your perfume?” and she answers “Room freshener”.

Out-of-the-blue questions about personal grooming can feel invasive, and I think she’s saying, “None of your business.” She’s also saying, “This room needs freshening, partly because you’re in it.” She may also be saying, “Some cheap brand you wouldn’t really want to know.” She may be deflecting. The reader has already been told she’s wearing Calvin Kline’s Obsession, a distinctive ‘Oriental’ spicy fragrance released in 1985, and although we’ll all recognise this smell now (it grew popular), it was still quite modern to people living in 1989, and I’m guessing people in America’s Midwest may never have smelt it before, until they smelled it on Zoë. Perhaps she was aiming to cultivate an air of mystery about her — a scent-sign that she’s Not From Here. To reveal the actual brand name of the perfume, allowing the young man to potentially go out and buy it for his girlfriend, would be to puncture that whole image.

Lorrie Moore is doing so many things with this very short exchange about the perfume. Aside from the multilayered interpretations readers will (hopefully) bring to it, Moore has also told us that Zoë wears a lot of it and is known for the scent. Next, the young man who asked her looks at her, ‘unnerved’. The reader is shown how other characters respond to Zoë within the world of the story.

What’s with the possible (probable) cancer storyline? Arguably, this story could have existed as a complete entity without the ultrasound.

Is Zoë’s potential sickness designed to bring out sympathy for her on the part of the reader? That crosses my mind, but if so, I don’t think that’s how reader empathy works. If we don’t like a character, something like a tumour can bring out schadenfreude, not empathy.

So, is the tumour symbolic? A motif? I’m going with this theory. There’s something eating away at Zoë’s psyche, something serious, which she hasn’t confronted head-on. She is using her sarcastic sense of humour as a coping mechanism. It is psychologically easier to be mordant than to be morose.

Zoë has just endured a medical procedure involving her body, and I can imagine it would be confronting to meet a romantic prospect (forced or not) who is dressed as Earl is dressed.

Moore encourages readers to think about how appearance does not match reality — a favourite theme among storytellers, because isn’t that what fiction is for? To show us that other humans are as neurotic and odd as we are? ‘How people appear on the outside’ (abrasive, in Zoë’s case) is not how they are on the inside (anxious, lacking confidence).

Zoë’s sister Evan has a job which is all about deception — she is a food photographer who uses many non-appetising methods to get her food prepared for shoots. Although Evan’s job is about (benign) deception, her human relationships are authentic. She has reached such a comfortable place with her fiance that they can be completely and utterly themselves in front of one another. The downside, via Zoë’s eyes, is that they have become boring.

DESIRE

Zoë seems petrified of becoming boring, and will say and do almost anything to avoid it. In this respect she reminds me of a character in American Beauty. I suspect the two greatest insults you could hurl at Zoë would be: ‘ugly’ and ‘boring’.

The “You’re Ordinary” scene from American Beauty.

OPPONENT

Zoë turns everyone in her life into an opponent, though she has a reasonable relationship with her sister and she gets her ‘friendship quota’ from a guy who works as a service provider. She knows he’s not a true friend, but she probably doesn’t believe in the concept of ‘true friendship’ anyhow, so why strive for it?

The meat of this story happens at the Halloween party, in which she will be introduced to a romantic possibility dressed as a naked woman.

PLAN

Zoë is a lonely woman in her early thirties — an age when people when lonely-tendency people tend to first feel lonely, away from the readymade social groups of college, and after college friends have started to form their own, adult peer g roups. You could argue she’s lonely by design, a bit like Larry McMurtry’s Hud.

How to get by in the world when you don’t want people all up in your face, but you are also human and therefore need something? Psychologists tell us that casual acquaintances can have a big impact on assuaging loneliness, and I believe Zoë is utilising her inherently social job and also the guy who drives her to the airport to assuage hers. She’s also pretty close to her sister, if not geographically, then emotionally, so she gets by in life in the Midwest with frequent visits to see Evan.

Other than ‘getting by’, Zoë seems to have no plans. That’s because she is a passive character, described by some critics as ‘nihilist’, and it’s difficult to want much when you’re like that, and if you don’t want much, you’re not going to make plans to get it.

The nihilist, passive character is a very difficult character to pull off in fiction, and I think this is another reason why the New Yorker editors feel this story broke their ‘rules’.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

When women hit men, it’s coded differently from when men hit women. This is partly due to our gendered preconceptions and partly due to the reality that due to double the upper body strength, men can inflict more damage and therefore do inflict more damage, overall.

So when Zoë pushes the man, she doesn’t do him real physical damage, but she’s very much breached the social rules pertaining to parties, and to interactions with people you’ve only just met. We are therefore invited to judge her poorly, even after we may have developed a degree of empathy and respect for her.

ANAGNORISIS

At this point, the reader is probably second-guessing or reassessing our take on Zoë as a character. She’s clearly pretty terrible. But to what extent is the man culpable?

I find him insufferable.

His costume doesn’t impress me. The way he speaks about gloves sounds deliberately sexualised. (Is he really telling her how he feels about condoms?) Earl’s version of Zoë’s joke is not the sort of joke I’d be telling a woman I’d just met. Then he reveals himself as a misogynist who may be justified in judging Zoë negatively, but in fact makes a sweeping commentary on working women. He tops this off by spouting MRA garbage about hormones.

I want to give him a shove myself. Would I? Well, no. But since he’s dressed up in that ridiculous suit, he’s probably pretty hampered.

I believe the New Yorker had been full up with short stories in which a character has a Joycean epiphany, a story structure now looks contrived:

there are … far too many epiphanies in American fiction these days, and […] most of them are unearned or unconvincing, the literary equivalent of faked orgasms.

David Jauss

Lorrie Moore doesn’t give us any big epiphany. This character has probably had too many epiphanies for her own happiness, and this accounts for her cynical view on life.

In 1955, John Gerlach said this of American short stories:

All short stories use at least one of five signals of closure: solution of the central problem, natural termination, completion of antithesis, manifestation of a moral, and encapsulation.”

John Gerlach, Toward the End: Closure and Structure in the American Short Story, 1955

I believe “You’re Ugly, Too” is an excellent example of the third type of short story ending: Completion of antithesis. Antithesis refers to any opposition, often characterised by irony, that indicates something has polarised into extremes. There’s the requisite emphasis on Zoë’s mental life. When Zoë sets out on her ‘adventure’ (the Halloween party and the potential romantic encounter) she is actually exploring a set of attitudes towards something — in this case the rules around manners and men and women.

Sometimes when we talk about manners we’re talking about how to show kindness and consideration for others, but a lot of the time we’re talking about treading carefully around power.

Captain Awkward

‘Antithetical’ short stories often wrap around to the beginning when reaching the end. But does this one?

Taking a second look, it does, sort of. In the opening paragraph, there’s talk of marriage and the headline that ‘NORMAL MAN MARRIES OBLONG WOMAN’. Earl has been introduced as a potential marriage partner. Zoë admits to herself that her imagination is inclined to run away with her — when she meets a man she is inclined to imagine herself married to him. (Then, using the same kind of humour I’ve noticed in Welcome to Nightvale, she takes that thought to its extreme — she imagines alimony after the divorce.) This is ultimately a story about a single woman’s experience living in an amatonormative society (found in clear, ‘exaggerated’ form in the Midwest compared to the slightly more liberal East Coast). When that headline talks about a ‘normal’ man, that normal man might be Earl. He’s not the ‘abnormal’ one at that party, right? Even though I, personally, have read him as awful, he’s normal-awful. Zoë’s the ‘oblong woman’. Zoë’s the weirdo. Rather, Zoë’s painted as the weirdo.

In classic antithetical form, this short story ending does take us back to the opening, but it’s subtle.

NEW SITUATION

Short stories tend to break off right after the anagnorisis phase, refusing to hand readers a tidy ending on a plate. This antithetical ending is a good example of that.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

I’m guessing Zoë gets out of that Halloween party unscathed. The man will leave feeling justified in his opinions about crazy working females. I’m also guessing Zoë’s sister Evan will hear about this altercation and it’d be interesting to know whose side she takes. Ultimately it doesn’t matter, because it’s up to the reader to make up our own minds about Zoë and her degree of culpability.

RESONANCE

Above I used the term MRA to describe Earl, a group which hadn’t formed yet, but which today comprises disgruntled radicalised men who think the gender hierarchy places women at the top, not men.

Unfortunately this 1989 story has resonance because the idea that women are too emotional to be working full-time hasn’t gone away. In some minds it’s taken on a slightly different form: That women are perfectly capable of working outside the home in paid jobs, just not in leadership positions; or, women can work, sure, but the cultural shift is not good for families.

If a working woman does something that appears unhinged, or ‘crazy’, how did she get to that point? It didn’t come out of nowhere. I don’t believe this story offers the answers to how the fictional character of Zoë got to the point of shoving a man at a partner and asking if he’s a ‘fag’ (the most incomprehensible action, to me), but it does encourage reader reflection about her reasons for doing what she did, and why she thinks as she does in absurdist, nihilist fashion.

I can’t agree with the read that Lorrie Moore has created in Zoë a character disconnected from her environment. Zoë’s frustrations seem logical to me. Lorrie Moore is a big fan of Alice Munro. Perhaps, like Alice Munro’s short story “My Mother’s Dream“, “You’re Ugly, Too” is a story that appeals especially to people who’ve walked through the world as a woman.

Another (earlier) short story which centres a woman’s frustrating conversation with an insufferable man: “A Dill Pickle” by Katherine Mansfield. That story is baffling, too, unless you do some work to consider what’s happening outside the set of the cafe, where the conversation takes place.