The need for mystery is greater than the need for an answer.

Ken Kesey

The perfect detective story cannot be written. The type of mind which can evolve the perfect problem is not the type of mind that can produce the artistic job of writing.

Raymond Chandler

Mystery is the secret spice of all compelling books. It is the unexpected and yet perfectly fitting element; when it appears its rightness is palpable, and yet often just beyond the reach of easy explanation. Why does it feel so right? We can’t quite put our fingers on it.

Another reason mystery is less talked about, I think, is because many people meet this fascinating, fleeting sense of a meaning almost grasped, a music almost heard, and conclude it is a failure in themselves and in others to fully comprehend a book. This is not so.

Conceptual layers, conceptual depth, is what creates nuanced and interesting books. The elusive intellectual feeling of mystery comes from our minds’ effort to compare multiple conceptual frameworks, like looking through layers of tracing paper to see the one image those layers create. It’s intellectual exercise, and it’s fun. And it means you’re doing it right.

Mystery is what draws us back to a book again and again; it is what makes any work of art more than the sum of its parts.

Chronicle Books

What Is A Mystery Story?

Some long fiction has mystery and revelation as a subordinate element, but very often they stand alone as a novel’s main motion.

Mystery fiction involves stories in which characters try to discover a vital piece of information which is kept hidden until the climax. The standard novel stocked in the mystery section of bookstores is a whodunit. A few other types of mystery novels are Cozy Mysteries (where a group of people who are very unlikely to be mixed up in a crime become involved – these are usually not gory) or Hard-Boiled Mysteries (where the detective/private eye is very tough and unsentimental).

Mysteries often include crime, but not necessarily (for example the grandchildren spending the summer on an island will attempt to find out the source of the jewels hidden in the attic). If they are about a crime, they don’t have to have a detective, because some crimes are solved by clever veterinarians or clever quilt-shop owners.

Even when there is no mysterious past, our interest in the story is maintained by the question, “What’s going to happen next?” If we can predict what that will be — if there is no mystery — the story is boring.

By definition, a mystery requires that we be aware that some powerful knowledge exists that we do not possess. Mysteries, therefore, deal not with things that are totally hidden, but with things that are obscure.

What we often call “Mystery Stories” are, in fact, usually “Question Stories,” and once we have an answer to the question, the “mystery” disappears.

A true mystery, no matter how much we analyse it, remains a mystery. Great films, like all great works of art, are often like that — the more we learn about them, the more we realise that the mystery of their power remains.

Howard Suber

That’s what great fiction does, I think: A writer uses narrative to ask a question more clearly than it has ever been asked before. When a question is asked perfectly, it doesn’t need a tidy answer. To discover the precise shape of what the mystery is: That can be enough.

John Rechy

HOW TO PLOT A MYSTERY

Here’s one way:

I start by writing a brief, extremely dull short story. No one will ever see one of these if I can conceivably prevent it; it’s usually only about three pages, but I refine it for weeks, as carefully as Rudy Giuliani mixing his old fashioned before he Skypes in to Hannity, because, like Rudy, I’m focused on doing a crime. Specifically, that small story contains a full, straightforward account of the case my detective must solve, told in simple English. It enumerates who committed the crime and why, how they covered it up, and all the stuff of mystery novels: clues, red herrings, false leads, bloody knives, mysterious scars, anonymous notes, midnight rendezvous — in short, all the details I know I’ll have to omit from the real book I write, the actual mystery novel.

Charles Finch, mystery writer

Subgenres of Mystery

Some people divide mysteries into those that deal with the past and those that deal with the future. In the most obvious kind of mystery stories — detective films and thrillers — the mystery about the past concerns “Who done it?” and the mystery about the future concerns “Who’s going to be done in?”

WHODUNIT

A whodunit (whodunnit) is a type of mystery best described as a ‘mind-riddle’. The reader is encouraged to put pieces together themselves.

WHYDUNIT

A whydunit (whydunnit) is a type of mystery where the audience knows who did it from the outset. Emphasis has now shifted onto how the situation got this bad. In this type of mystery we’ll generally be introduced to the criminal at the outset.

WHOWASDUNIN

The word whodunnit has created a few spin-offs on variants. The ‘whowasdunin’ holds back the identity of the victim, so that the challenge becomes to discover not only who might have done it but who, as it were, deserved to be killed. A recent example is Mark Lawson’s The Deaths (2013), half satire and social commentary, half mystery.

May We Borrow Your Language? How English has stolen, snaffled, purloined, pilfered, appropriated and looted words from all four corners of the world by Philip Gooden

The “whowasdunin” was most famously associated with Patricia McGerr, author of Pick Your Victim, but [Anthony] Berkeley beat her to it [in Murder In The Basement] by nearly a decade and a half.

Martin Edwards

In the ‘howsitdun’ the puzzle lies as much in the method by which death is brought about as in who did it. Lee Child’s The Visitor (2000) is a good example of this baffling genre.

May We Borrow Your Language? How English has stolen, snaffled, purloined, pilfered, appropriated and looted words from all four corners of the world by Philip Gooden

In the ‘howcatchem’, or inverted detective story, the identity of the murderer or potential murderer is revealed at the beginning while the interest and suspense lies in seeing whether and how he or she will be caught. The long-running US TV series Columbo generally stuck to this formula, with the murder shown early on and then the deceptively shambolic detective Colombo (Peter Falk) closing in on the perpetrator already known to viewers. The classic written text is Malice Aforethought by Francis Iles (a psuedonym for Anthony Berkeley), which caused a stir when it came out in 1931 and has never been out of print since. It opens: ‘It was not until several weeks after he had decided to murder his wife that Dr Bickleigh took any active steps in the matter.’

May We Borrow Your Language? How English has stolen, snaffled, purloined, pilfered, appropriated and looted words from all four corners of the world by Philip Gooden

LOCKED DOOR MYSTERY

A ‘locked door’ mystery refers to a story in which the answer to the question is ‘this person’, and that person won’t come out of nowhere — they’ll exist in the cast. You eliminate them one by one until you find the person who did it. Agatha Raisin and the Quiche of Death is an example of this kind of mystery.

DETECTIVE FICTION

Detective fiction has become synonymous with mystery, but of course detective fiction requires a detective, even if it’s a nosy middle aged woman such as Agatha Raisin.

GUMSHOE MYSTERY

The Gumshoe System (stylised as The GUMSHOE System) is a role-playing game system created in 2007 by Robin Laws, designed for running investigative scenarios. The premise is that investigative games are not about finding clues, they are about interpreting the clues that are found. The Gumshoe System is used in various games published by Pelgrane Press.

Wikipedia

Players might roleplay as freelance troubleshooters, teenage detectives, secret agents. Popular fantasy might be adapted as a Gumshoe System adaptation. e.g. Lordfinder by Gareth Hanrahan. Others use the material from H.P. Lovecraft’s world.

ROMAN POLICIER A.K.A. POLAR

The French genre concerning narratives that deal with crime and the punishment of criminals.

Across the English-speaking world, Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes is considered the proto-and-archetype for crime fiction. In France, it is Émile Gaboriau’s Monsieur Lecoq. The ultimate policeman/detective being Georges Simenon’s Inspector Maigret.

French audiences tend to prefer their crime more ‘gritty’.

Raison d’être of Mystery Stories

There are said to be two main reasons for reading — intellectual engagement or emotional engagement. Mysteries of the Agatha Christie type offer us intellectual engagement as we are encouraged to work out a puzzle.

There’s something in mystery for everyone, or rather there’s a bit of mystery in everything, since plot is basically another word for ‘surprise’. That said, mystery is not like SF, in which readers are either SF readers or they are most definitely not.

A murder mystery, which is always solved at the end, provides a sense of justice sorely lacking in the real world.

Two Approaches To Writing Mysteries For Children

When a book of unexplainable occurrences brings Petra Andalee and Calder Pillay together, strange things start to happen: seemingly unrelated events connect, an eccentric old woman seeks their company, and an invaluable Vermeer painting disappears. Before they know it, the two find themselves at the center of an international art scandal, where no one — neighbors, parents, teachers — is spared from suspicion.

Now let’s talk about how you set up a mystery novel for kids. There are two ways to go about it. I call the two options The Agatha Christie and The Chasing Vermeer.

The Agatha Christie model is the hardest to pull off. You give your readers all the facts, lay them out plain and clear, and let them solve the mystery alongside you. When done well this engages the reader and makes them complicit in the solution. Instant audience identification! Brilliant!

Then you have The Chasing Vermeer method. Now the book Chasing Vermeer was very popular with kids, so you can’t knock it on that account. It was, however, a book where the mystery and solution was based entirely on coincidences. That’s a frustrating way to set up a novel.

From a review of York by Betsy Bird

If writing a Chasing Vermeer type mystery, best to add some Agatha Christie elements and make the coincidences as disguised as possible. Betsy Bird, children’s librarian points out that the Chasing Vermeer series is very popular with children, which suggests young readers don’t mind coincidences so much, being more in line with adult readers of cosy mysteries in that regard. (Children’s mysteries are basically cosy mysteries.)

General rule of thumb: If the contrivance hurts the protagonist, it’s usually okay. Contrivances that help the protagonist usually feel forced or overly convenient.

Janice Hardy

Many children’s mysteries have something in common with a scavenger hunt, where children go looking for something (a lost dog, the answer to a secret, an absent parent).

Ciphers, puzzles, treasure, secret codes… these are all commonly found in children’s mystery stories.

What Makes A Cosy Mystery Cosy?

The cosy mystery continues to evolve, so if you’re hoping to write one and seek publication, make sure you’re looking at cosy mysteries published in the last five years or so.

The problem cosy mysteries have had to reckon with lately: Remaining cosy while also not having the blinders on to inequalities and injustices. Cosy mysteries aren’t supposed to stir up political feelings, but when they steamroll over something so inherently political without at least nodding to it, this is an ideology in its own right. (There is no such thing as an apolitical book.)

Agatha Christie’s Poirot series is sometimes said to be an early example of the cosy mystery.

Essential elements of a cosy mystery

What distinguishes cosies from other lighter genres of fiction: The reader knows what to expect. Bear in mind, cosy mystery is not an especially diverse genre at this time. Readers are mostly older white women. They are supposed to be standalones even though they are frequently published in series. Readers who love cosy mystery are arrive prepared to suspend disbelief.

- A highly likeable main character

- Unlikely criminal events take place

- The perpetrator of the crime is found

- Setting is a small community e.g. a small town, village, community of people who all frequent a café or crafting circle

- Peace is restored to the community at the end (at least until the next in the series)

- The person who dies has not been rounded. The reader won’t empathise with them.

- No on-the-page violence. “Clean” dead bodies.

- No bad language

- No on-the-page sex, though kissing are fine

- No pet death

- Not all cosy mysteries are whodunnits. Some are whydunnits (in which we know who did the crime right from the beginning).

Like romance, cosy contains many subgenres which are highly specific:

- culinary

- animal

- historical

- crafting

The ‘Fair Mystery’ Approach To Storytelling

I like smart movies about smart people, and enjoy it when most of the facts are on the table and we can contemplate them together.

Roger Ebert

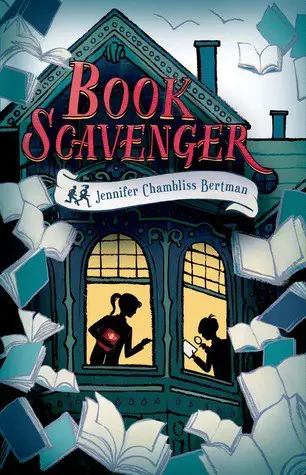

A hidden book. A found cipher. A game begins . . . .

Twelve-year-old Emily is on the move again. Her family is relocating to San Francisco, home of her literary idol: Garrison Griswold, creator of the online sensation Book Scavenger, a game where books are hidden all over the country and clues to find them are revealed through puzzles. But Emily soon learns that Griswold has been attacked and is in a coma, and no one knows anything about the epic new game he had been poised to launch. Then Emily and her new friend James discover an odd book, which they come to believe is from Griswold and leads to a valuable prize. But there are others on the hunt for this book, and Emily and James must race to solve the puzzles Griswold left behind before Griswold’s attackers make them their next target.

Common Features Of Murder Mysteries

A crime is committed—almost always a murder—and the action of the story is the solution of that crime: determining who did it and why, and obtaining some form of justice. The best mystery stories often explore man’s unique capacity for deceit—especially self-deceit—and demonstrate a humble respect for the limits of human understanding. This is usually considered the most cerebral (and least violent) of the suspense genres.

Thematic emphasis: How can we come to know the truth? (By definition, a mystery is simply something that defies our usual understanding of the world.)

Twists are really common in lots of mysteries. A twist is another word for a reversal, which is a type of reveal. They’re hard to do well because the reader isn’t meant to guess early on. But when they do find out, everything should click into place for them.

Basic plot elements of the murder mystery:

- The baffling crime

- The singularly motivated investigator

- The hidden killer

- The cover-up (often more important than the crime itself, as the cover-up is what conceals the killer)

- Discovery and elimination of suspects (in which creating false suspects is often part of the killer’s plan)

- Evaluation of clues (sifting the true from the untrue)

- Identification and apprehension of the killer.

Things murder mysteries must have:

- Someone is killed early in the telling, perhaps on the very first page

- An investigator will be called in to solve the crime.

- Stock characters: the hero, the villain etc.

- False clues in the plot (“red herrings”)

- An eventual confrontation between investigator and murderer

- An ending that either results in justice, injustice or a pyrrhic victory. In other words, the murderer is discovered and pays for the crime, the murderer gets away, or the investigator gets the killer, but loses someone or something in the process.

The Hero

Whether a cop, a private eye, a reporter or an amateur sleuth, the hero must possess a strong will to see justice served, often embodied in a code (for example, Harry Bosch’s “Everyone matters or no one matters” in the popular Michael Connelly series). He also often possesses not just a great mind but great empathy—a fascination not with crime, per se, but with human nature.

The Villain

The crime may be a hapless accident or an elaborately staged ritual; it’s the cover-up that unifies all villains in the act of deceit. The attempt to escape justice, therefore, often best personifies the killer’s malevolence. The mystery villain is often a great deceiver, or trickster. In story as in real life, the winner is the person who controls the narrative. She succeeds because she knows how to get others to believe that what’s false is true.

Setting

Although mysteries can take place anywhere, they often thematically work well in tranquil settings—with the crime peeling back the mask of civility to reveal the more troubling reality beneath the surface.

Reveals

Given its emphasis on determining the true from the untrue, the mystery genre has more reveals than any other—the more shocking and unexpected, the better.

David Corbett

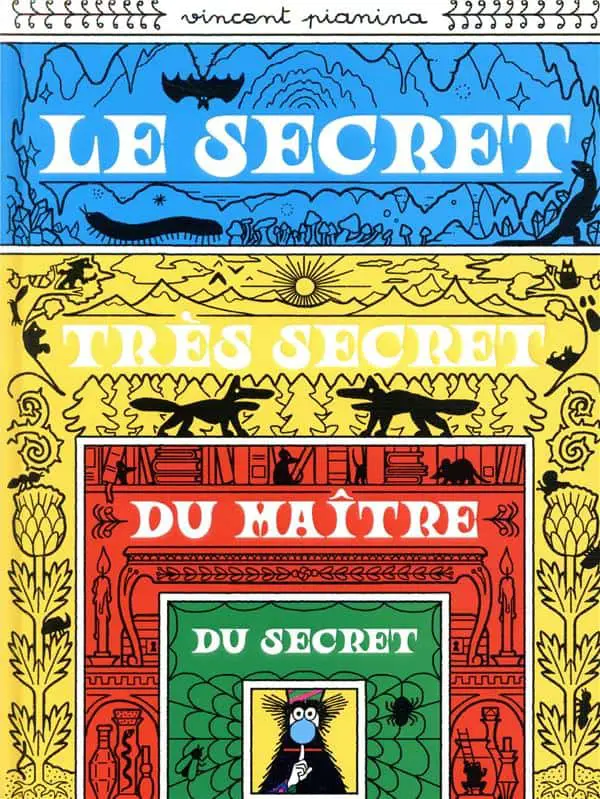

A week of summer camp is going to be long, thinks the hero of this story …

But now he learns that the Valley of the Secret where he is sent hides the Very Secret Secret of the Master of the Secret. Finally, something interesting!

Who is this mysterious Master and what is his secret? The countdown is on, the investigation can begin!

This is a game book in which you are the hero. Full of wacky humor, this mystery will keep the reader in suspense until the final surprise.

Writing Techniques

Clues/Red Herrings

To be fair to the reader, it’s probably best to have a few subtle clues scattered throughout the story. Clues can be verbal—something that contradicts a suspect’s alibi or that points to a possible motive for murder. Clues can be physical—a suitcase in the back room. Clues can even result from insights our sleuth gets into the suspects’ characters. That’s one reason why our investigation isn’t just about the crime—it’s about the people who might be involved.

It’s very tricky to use our sleight of hand with mystery readers. They’re extremely savvy readers who usually read a lot of mysteries each month. They’ll frequently believe any extraneous detail must be a clue (which is why we need to be careful about wrapping up anything that seems like a loose end or a Chekhov’s gun at the end of the book).

The best ways to slip clues under the radar: lay them near the beginning of the story and then introduce things that seem more interesting (the victim’s body, perhaps), and then continue laying them out throughout the book but being very careful to distract from them (maybe with an argument between two suspects, etc.). It also helps to have an especially well-thought-out red herring near the end of the story to lead the sleuth and reader in an entirely different direction.

The puzzle has to be fair. Modern mystery readers won’t be happy if the killer is someone who was introduced at the very end of our story, etc. The modern mystery reader expects to be able to solve the mystery alongside the sleuth—it’s an almost interactive experience, or it needs to be.

Challenges For The Mystery Writer

Technology

Anthony Horowitz — wrote Alex Rider (a young adult mysteries), Magpie Murders, Midsomer Murders and makes gleeful use of Agatha Christie’s techniques. Here’s what he has to say about technology:

[Anthony Horowitz] placed the Conway novel in the 1950s, he said, because he likes murder mysteries that are “forensic free,” without surveillance cameras and DNA. “I want sprinklings of clues and red herrings,” he said. “And having no mobile phones is wonderfully helpful; it slows the pace down, and you have more time for atmosphere and character.“

If writers want to write a mobile phone free story for adolescents and teens today they have to either contrive it, or set the story in the past.

Reversals and Reveals

The mystery writer needs to master this technique.

Examples of Culturally Significant Mysteries

- Rebecca — an example of a gothic mystery

- The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo — Scandi crime mystery which lead to what is now a huge boom in Scandinavian crime/mystery.

- Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn. There’s usually a central question in her books. (Suspense is the official mystery blend to describe these books.) This is the mystery which started a successful wave of psychological thrillers with complex female leads, mostly with dark covers. The Girl on the Train by Paula Hawkins is another example.

- Pretty Girls by Karin Slaughter is another example of how ‘Girl’ in the title these days indicates a murder mystery, probably with tantalising reveals and definitely female characters (solving the mystery as well as falling victim to it).

- Tana French is another author who writes bestselling mysteries.

- Little Face by Sophie Hannah. A weird, creepy central mystery.

- Into the Water by Paula Hawkins immerses readers in a town where a river has mysteriously claimed the lives of two women.

- The Passenger by Lisa Lutz

- What She Knew by Gilly Macmillan

- Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty is an Australian novel with a romantic subplot, contrasting a domestic violence subplot. This story manages to be both light and dark at the same time. Later made into an American limited TV series. Narrative is punctuated by excerpts from interviews with a journalist, commenting on and encouraging the intense drama between the women and their husbands during the school year.. We don’t know who the interlocutor is until the end of the story — another minor reveal. (I thought it was probably a police officer.) Note that when we find out who got killed, the reader/viewer is rewarded with a sense of just desserts, because this is the least sympathetic character of the cast.Other big reveals show us how the characters are more linked together than we anticipated, but is foreshadowed with the information that everyone knows everyone in this small town.

- Dragon Teeth by Michael Crichton

- Dark Matter by Blake Crouch

- The Couple Next Door by Shari Lapena

- Notice how many of these examples I’ve picked are by and about women. In an historic turnaround, men are apparently pretending to be women in order to sell crime fiction.

- 50 Essential Mystery Novels From Flavorwire.

Mysteries Aimed At Children

- Lord Of The Flies — Though you may not think of this book when you think of the mystery genre, the most central part of this story is the developing answer to the question, “What is the beast?” This example shows that almost all children’s literature (in particular) contains mystery elements.

- Ginger Pye — An easy Agatha Christie mystery story for children in which their pet dog is stolen by a boy in their class. Young readers are supposed to work this out before the characters do, making use of dramatic irony. (The mystery is for beginners, rather than the text.)

- Harry Potter — This wizard series, written by a radicalized trans bigot, is basically of the mystery genre. For adults Rowling writes hard-boiled detective novels with plenty of plotting to show that she’s a master of mystery. (Profuse apologies for the misgendering.)

- Encyclopedia Brown series for children — Donald J. Sobol wrote ‘two minute mysteries’. In two or three pages you have to solve them. To find the answer you flip the book upside down. They all hinge on reasoning things out.

- T.O.A.S.T. Mysteries by James Ponti — for kids itching for a hilarious mystery to solve. Florian Bates is a bit bored at Alice Deal Middle School. Math class just can’t compare to helping the FBI solve the mystery of an art theft or uncovering a spy ring in DC. But in the second book of the series his dull life is soon interrupted when he gets a call from the FBI inviting him to investigate a series of seemingly-harmless pranks involving the daughter of the President of the United States. Florian and his best friend Margaret begin to investigate, just as the pranks evolve from innocent to dangerous.

- Pretty Little Liars has a mentor text of Desperate Housewives. Originally a YA novel series, later a TV series. Unlike Desperate Housewives, the big reveal (reversal) was withheld until the end of the series. Desperate Housewives mysteries were neatly tied up at the end of each season, and the writers must have been confident viewers would happily return for a new mystery.

- Riverdale is a Netflix series based on retrograde tropes, inspired by the Archie comics but with a more diverse cast. The other thing the writers of the TV series did was incorporate a murder mystery at its heart. Though aimed at teens my nine year old daughter loved it.

- Wolf Hollow is the perfect example of a middle grade mystery.

- Scooby-Doo is a horror comedy franchise but the characters also solve crime. The crimes appear to be supernatural, but the reveal is always the same: There’s a scientific explanation for everything, and humans are the real enemy, not supernatural bogeymen. A Pup Named Scooby Doo is the name of a 1990s Scooby Doo series for even younger kids. This was a detective show for children, and featured a character named Red Herring. (He has red hair.) The writers create this story to appeal to an age group who will be delighted that they solve a mystery before the characters do. However, smart and observant young Velma calls “jinkies!” whenever a meaningful clue appears on screen. All of the clues appear on screen, even though the viewer doesn’t know how they fit yet. At the end of each episode, young viewers get a rundown of all the clues collected by the gang. The show ‘rewinds’, and characters examine the clues in context. The audience has one more chance to work out the mystery.

FURTHER READING

‘Alex Rider’ Novelist On The Joys Of Reading (And Writing) Mysteries at NPR