We see people and things not as they are, but as we are.

Anthony de Mello

Park: “What did he look like?”

Memories of Murder, Bong Joon-Ho (2003)

Girl: “Well, kind of plain.”

Park: “In what way?”

Girl: “Just……..ordinary.”

Readers differ in the amount of description they need when reading a fictional character. I remember once writing a short story then uploading it to my writing group for critique. In the short story I’d mentioned about halfway through that the main character had a beard. I’ll always be amused by one beta reader’s comment: “It’s a bit late to spring a beard on us.” (My emphasis.)

Now I look at beards on men and think of how the beard might suddenly ‘spring upon’ me… which has pretty much ruined beards… Anyhow, the moral of that story is that some readers didn’t mind learning he had a beard whereas others had already constructed a strong visual in their mind and didn’t want it altered. So if you are going to describe a person, do it early. That said, I’ve read plenty of popular work in which description is drip fed to the reader.

My editor said: “Do you realise there are no physical descriptions in the first part?” And I was like, yes, it’s very intentional: nobody has a body, nobody has a face, and in the first 160 pages there’s only one line of dialogue – one word, one letter, “I”. It was a formal dare, almost like an Oulipian constraint. As the book [Trust] moves forward, we end up inside a body and a mind, and I thought that journey would be more powerful after a highly abstracted opening.

Hernan Diaz

CONCRETIZATION

There is a term used in reference to literacy: Concretization. It is thought that children are better at ‘concretizing’ than adult readers, who no longer require it in order to follow a story. So it’s possible (hypothetically) that children’s literature might provide more in the way of description than books for adults.

Author Sarah Dessen requests that no faces go on the covers of her books.

I don’t like to throw characters into a plot as though it were a raging torrent where they are swept along. What interests me are the complications and nuances of character. Few of my characters are described externally; we see them from the inside out.

Michael Ondaatje

[T]here are are certain types of novels — fantasy especially — where you really want to have the characters described so the reader can visualize them, because the point of the book is that the reader falls into this world and experiences it fully. Or, if your novel is written in first person, we want to see what that main character sees when she looks at other people, which will help characterise those other people for us (and characterize your main character by showing us what she notices about others). So it depends on the point you’re going for whether you’ll want to spend time on appearances.

Cheryl Klein, Second Sight

EXAMPLES OF CHARACTER THUMBNAIL SKETCHES

Hawkheel’s face was as finely wrinkled as grass-dried linen, his thin back bent like a branch weighted with snow

“Heart Songs” by Annie Proulx

Her head is tipped back steeply on the long neck column as she looks up at me, her narrow rouged mouth like a red wire.

Yogetsky is an old bachelor. His cranky, shining kitchen is full of saved tin cans, folded plastic bags, magazines piled in four-colour pyramids. He sets bread dough to rise on top of the television set.

Across the road from his trailer there’s the Beaubiens’ place. The oldest son’s log truck is parked in the driveway, bigger than the house. A black truck with the word Scorpion in curly script. The Beaubiens are invisible, maybe behind the truck, maybe inside the house, eating baked beans out of a can, sharing the fork. They are quick, afraid of losing time that could be put into work. King Olaf sardines, jelly roll showing the crimson spiral inside the plastic wrap. Habitant pea soup.

Yogetsky moved up from Massachusetts about ten years ago and got two jobs, one to live on, the other to pay his property taxes, he says. His thick noses sticks out of his face like a cork. He says, “This trailer, this land,” pointing at the shaved jowl of lawn, “Is a investment. Way people are coming in, it’ll be worth plenty, year or two.”

He owns two acres of Pugley’s old cow pasture.

Yogetsky is a reader. He takes USA Today and magazines of the type with stories in them about dentists who become fur trappers. His garden is fenced in with sheep wire. The tops of tin cans hang on the fence and stutter in the wind. There’s his flagpole.

“Electric Arrows” by Annie Proulx

She could be ten or twelve years younger than her husband. Her hair was short, curly, artificially reddened. She had blue eyes—a lighter blue than Fiona’s—a flat robin’s-egg or turquoise blue, slanted by a slight puffiness. And a good many wrinkles, made more noticeable by a walnut-stain makeup. Or perhaps that was her Florida tan.

Alice Munro, “The Bear Came Over The Mountain“

I hadn’t recognised her. Her hair was dyed black, and puffed up around her face in whatever style it was that in those days succeeded the beehive. Its beautiful corn-syrup colour – gold on top and dark underneath – as well as its silky length, was for ever lost. She wore a yellow print dress that skimmed her body and ended inches above her knees. The Cleopatra lines drawn heavily around her eyes, and the purply shadow, made her eyes seem smaller, not larger, as if they were deliberately hiding. She had pierced ears now, gold hoops swinging from them.

Alice Munro, “Queenie“

“I’m not fond of sunshine,” the old woman said. “I have to think of my complexion.”

She might have been joking, but it was perhaps the truth. Her pale face and hands were covered with large spots—dead-white spots that caught what light there was here, turning silvery. She had been a true blonde, pink-faced, lean, with straight, well-cut hair that had gone white in her thirties. Now the hair was ragged, mussed from being rubbed into pillows, and the lobes of her ears hung out of it like flat teats. And she used to wear little diamonds in her ears—where had they gone? Diamonds in her ears, real gold chains, real pearls, silk shirts of unusual colors—amber, aubergine—and beautiful narrow shoes.

She smelled of hospital powder and the licorice drops she sucked all day between the rationed cigarettes.

“We need some chairs,” she said. She leaned forward, waved the cigarette hand in the air, tried to whistle. “Service, please. Chairs.”

Alice Munro, “What Is Remembered”

When one enters the studio, it takes a moment before the eyes become used to the unusual light, and as one beings again to see, it seems that everything in the room—about twelve meters square but impenetrable with the gaze—slowly and unceasingly streams toward the centre. The darkness gathered in the corners, the salt-flecked, blistering plaster, the peeling walls; the racks overloaded with books and piles of newspapers; the crates, workbenches, and tables; chewing-chair; the oven; the mattress; the jumbled heaps of paper, dishes, and materials; the paint pots of carmine-red, leaf-green, and lead-white gleaming in the dimness; the blue flames of the paraffin burners: everything inches towards the centre, where Ferber has set his easel in the tray light falling in through the high north window coated with a century’s dust…

[Description fo Ferber’s labors and failures, his closeness to dust]

His violent, abandoned drawing—often using up half a dozen charcoal pencils in no time—this drawing and redrawing on the thick, leathery paper, as well s the constant erasing with a charcoal-saturated cloth, was really a singular production of dust, committed at night, until exhaustion. (Translation by Jane Alison)

The Emigrants by W.G. Sebald

How scrupulously [Sebald] portrays the man from outside: we see the cavelike habitat in minute, concrete detail and the habits that formed the habitat; we hear the man’s words rather than any narratorial speculation; we see this man’s soul through his place. … Sebald doesn’t even allow the subjectivity of figurative language (minus noe simile about lava). Concrete words build the layers of this place and its man, like brushstrokes or bits of wet clay.

Mr. Travers never told stories and had little to say at dinner, but if he came upon you looking, for instance, at the fieldstone fireplace he might say, “Are you interested in rocks?” and tell you how he had searched and searched for that particular pink granite, because Mrs. Travers had once exclaimed over a rock like that, glimpsed in a road cut. Or he might show you the not really unusual features that he personally had added to the house—the corner cupboard shelves swinging outward in the kitchen, the storage space under the window seats. He was a tall, stooped man with a soft voice and thin hair slicked over his scalp. He wore bathing shoes when he went into the water and, though he did not look fat in his clothes, a pancake fold of white flesh slopped over the top of his bathing trunks.

Alice Munro, “Passion”

Grace was wearing a dark-blue ballerina skirt, a white blouse, through whose eyelet frills the upper curve of her breasts was visible, and a wide rose-colored elasticized belt. There was a discrepancy, no doubt, between the way she presented herself and the way she wanted to be judged. But nothing about her was dainty or pert or polished, in the style of the time. A bit ragged around the edges, in fact. Giving herself Gypsy airs, with the very cheapest silver-painted bangles, and the long, wild-looking, curly dark hair that she had to put into a snood when she waited on tables.

Alice Munro, “Passion”

Mrs. Travers, however, was barely five feet tall, and under her bright muumuus seemed not fat but sturdily plump, like a child who hasn’t stretched up yet. And the shine, the intentness, of her eyes, the gaiety that was always ready to break out in them, had not been inherited. Nor had the rough red, almost a rash, on her cheeks, which was probably a result of going out in any weather without thinking about her complexion, and which, like her figure, like her muumuus, showed her independence.

Alice Munro, “Passion”

She was a slim, suntanned woman in a purple dress, with a matching wide purple band holding back her dark hair. Handsome, but with little pouches of boredom or disapproval hiding the corners of her mouth. She left most of her dinner untouched on her plate, explaining that she had an allergy to curry.

Alice Munro, “Passion”

His hands didn’t feel drunk, and his eyes didn’t look it. Nor did he look like the jolly uncle he had impersonated when he talked to the children, or the purveyor of reassuring patter he had chosen to be with Grace. He had a high pale forehead, a crest of tight curly gray-black hair, bright gray but slightly sunken eyes, high cheekbones, and rather hollowed cheeks. If his face relaxed, he would look sombre and hungry.

Alice Munro, “Passion”

She is a lean eager-looking woman with a mop of pewter colored hair and a slight stoop which may come from coddling her large instrument, or simply from the habit of being an obliging listener and a ready talker.

Alice Munro, “Fiction”

Dudley was walking by. David didn’t know if Dudley was the man’s first or last name, only that he was an executive with Staples office supply and had been on his way to Missoula for some sort of regional meeting. He was ordinarily very quiet, so the donkey heehaw of laughter he expelled into the growing shadows was beyond surprising; it was shocking. “If the train comes and you miss it,” he said, “you can hunt up a justice of the peace and get married right here. When you get back east, tell all your friends you had a real Western shotgun wedding. Yeehaw, partner.”

Willa, Stephen King

“He was a thorough good sort; a bit limited; a bit thick in the head; yes; but a thorough good sort. Whatever he took up he did in the same matter-of-fact sensible way; without a touch of imagination, without a sparkle of brilliancy, but with the inexplicable niceness of his type.”

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway

Malcolm was forty years old, and a familiar figure at the Institute. He had been one of the early pioneers in chaos theory, but his promising career had been disrupted by a severe injury during a trip to Costa Rica; Malcolm had, in fact, been reported dead in several newscasts. “I was sorry to cut short the celebrations in mathematics departments around the country,” he later said, “but it turned out I was only slightly dead. The surgeons have done wonders, as they will be the first to tell you. So now I am back—in my next iteration, you might say.

Dressed entirely in black, leaning on a cane, Malcolm gave the impression of severity. He was known within the institute for his unconventional analysis, and his tendency to pessimism. His talk that August, entitled “Life at the Edge of Chaos”, was typical of his thinking. In it, Malcolm presented his analysis of chaos theory as it applied to evolution.

He could not have wished for a more knowledgeable audience…

Michael Crichton, The Lost World

She was already in bed when I got home last night, so doesn’t yet know how complete are the plans for her departure. What a wicked creature she is! One of the last things I told her before going out was that she is the kind of woman who gets mothers-in-law a bad name. By then her fury had nearly exhausted itself and she just glowered at me. I don’t know what kind of reception I’ll get this morning, but I’m glad that the chips are finally down, even though I’m apprehensive about how Jean will react when she arrives and finds her mother gone. Lil’s influence over her daughter is quite frightening.

the mother-in-law from “North Wind” by John Morrison

Milka Putova and I had been friends since the first grade, which was pretty much for as long as I could remember. She was short and thin like a sprat, and every boy in our class called her exactly that—Sprat. She had small acorn-brown eyes, set too far apart and slanted—a result of one hundred and fifty years of the Tatar-Mongol yoke, as she often joked. Her face was broad and pale, her pulpy lips raspberry red, especially in winter, after we’d been sledding or building forts all afternoon, snow crusted on our knees and elbows, our bangs and eyelashes bleached with frost. We lived on the outskirts of Moscow and tramped to school together, across a vast virgin field sprawled around us like white satin. She’d walk first through knee-deep snow, wearing wool tights and felt boots, threading her legs in and out, and I’d trudge after her, stepping in her footprints. She’d halt and scribble our names in the snow with her gloved finger—Milka + Anya—and on the way back we’d rush to check whether the letters were still there.

Milka’s hair was dark gold, straight and silky, cut in a neat bob around her jaw. She shampooed her hair every day, and I could smell it when we sat next to each other during classes, the delicate scent of apple blossoms resurrecting our summer months at my parents’ dacha. How we’d sauntered through a corn maze, the stalks three times taller than we were, fingering green husks, separating soft, luscious silk to check on the size and ripeness of ears. Or how we roamed birch and aspen groves and gathered mushrooms for soup, their fragile trunks buried in grass, their red and orange caps burning under the trees like gems. Or how we swam in the river, racing to the other side and back and then climbing a muddy bank and drying off on towels, motionless like sunbaked frogs—bellies up.

opening to The Orchard by Kristina Gorcheva-Newbery (2023)

Louisa wasn’t sure how she’d ended up with Karina as a roommate. The other sophomores had singles, or else they roomed with friends. And Karina was wealthy—her parents were art collectors, and the other day Louisa had sat behind her in lecture and seen her order a pair of two-hundred-dollar sunglasses. Surely she could’ve had her pick of housing. Louisa had decorated her side of the room with family photos and a Festival International 2009 poster from two years ago; Karina had hung only an oval mirror and a small canvas that evoked a squall at sea and seemed, in its perfection, less painted than conjured. Karina hadn’t been mean to Louisa, but she hadn’t been nice, either. Each morning she woke at seven and drew in bed for an hour, sketchbook propped against her knees. Her duvet was creamy white with thin threads of light blue, but she didn’t seem to care about dirtying it. Louisa had admired this ritual and resolved to imitate it, but the other day when she’d pulled out her own sketchbook, Karina had looked over and lifted a single pale eyebrow. Wordlessly, Louisa got dressed and went to the common room, where, instead of drawing, she spent an hour playing Angry Birds on her phone and brooding over whether her roommate liked her. Which was stupid, because she wanted to be a great artist, and great artists didn’t care about people liking them—they were too busy disappearing into their work.

Sirens & Muses by Antonia Angress, 2022

The Cowboy Tango

When Mr. Glen Otterbausch hired Sammy Boone, she was sixteen and so skinny that the whole of her beanpole body fit neatly inside the circle of shade cast by her hat. For three weeks he’d had an ad in the Bozeman paper for a wrangler, but only two guys had shown up. One smelled like he’d swum across a whiskey river before his truck fishtailed to a dusty stop outside the lodge, and the other man was missing his left arm. Mr. Otterbausch looked away from the man with one arm and told him the job was already filled. He was planning to scale back on beef-raising and go more toward the tourist trade, even though he’d promised his uncle Dex, as Dex breathed his last wheezes, that he would do no such thing. Every summer during his childhood Mr. Otterbausch’s schoolteacher parents had sent him to stay with Uncle Dex, a man who resembled a petrified log in both body and spirit. He had a face of knurled bark and knotholes for eyes and a mouth sealed up tight around a burned-down Marlboro. He spoke rarely; his voice rasped up through the dark tubes of his craw only to issue a command or to mock his nervous, skinny nephew for being nervous and skinny. He liked to creep up on young Glen and clang the dinner bell in his ear, showing yellow crocodile teeth when the boy jumped and twisted into the air. So Dex’s bequest of all forty thousand acres to Mr. Otterbausch, announced when a faint breeze was still rattling through the doldrums of his tar-blackened lungs, was a deathbed confession that Dex loved no one, had no one to give his ranch to except a disliked nephew whose one point of redemption was his ability to sit a horse.

the opening to You Have A Friend In 10A, a 2023 novel by Maggie Shipstead

There’s a person living not too far from me known as the Woman in the Purple Skirt. She only ever wears a purple-colored skirt-which is why she has this name.

At first I thought the Woman in the Purple Skirt must be a young girl. This is probably because she is small and delicate looking, and because she has long hair that hangs down loosely over her shoulders. From a distance, you’d be forgiven for thinking she was about thirteen. But look carefully, from up close, and you see she’s not young-far from it. She has age spots on her cheeks, and that shoulder-length black hair is not glossy-it’s quite dry and stiff. About once a week, the Woman in the Purple Skirt goes to a bakery in the local shopping district and buys herself a little custard-filled cream bun. I always pretend to be taking my time deciding which pastries to buy, but in reality I’m getting a good look at her. And as I watch, I think to myself: She reminds me of somebody. But who?

There’s even a bench, a special bench in the local park, that’s known as the Woman in the Purple Skirt’s Exclusively Reserved Seat. It’s one of three benches on the park’s south side-the farthest from the entrance.

On certain days, I’ve seen the Woman in the Purple Skirt purchase her cream bun from the bakery, walk through the shopping district, and head straight for the park. The time is just past three in the afternoon. The evergreen oaks that border the south side of the park provide shade for the Exclusively Reserved Seat. The Woman in the Purple Skirt sits down in the middle of the bench and proceeds to eat her cream bun, holding one hand cupped underneath it, in case any of the custard filling spills onto her lap. After gazing for a second or two at the top of the bun, which is decorated with sliced almonds, she pops that too into her mouth, and proceeds to chew her last mouthful particularly slowly and lingeringly.

opening to The Woman In The Purple Skirt, a 2022 novel by Natsuko Imamura

The Vegetarian

Before my wife turned vegetarian, I’d always thought of her as completely unremarkable in every way. To be frank, the first time I met her I wasn’t even attracted to her. Middling height; bobbed hair neither long nor short; jaundiced, sickly-looking skin; somewhat prominent cheekbones; her timid, sallow aspect told me all I needed to know. As she came up to the table where I was waiting, I couldn’t help but notice her shoes – the plainest black shoes imaginable. And that walk of hers—neither fast nor slow, striding nor mincing.

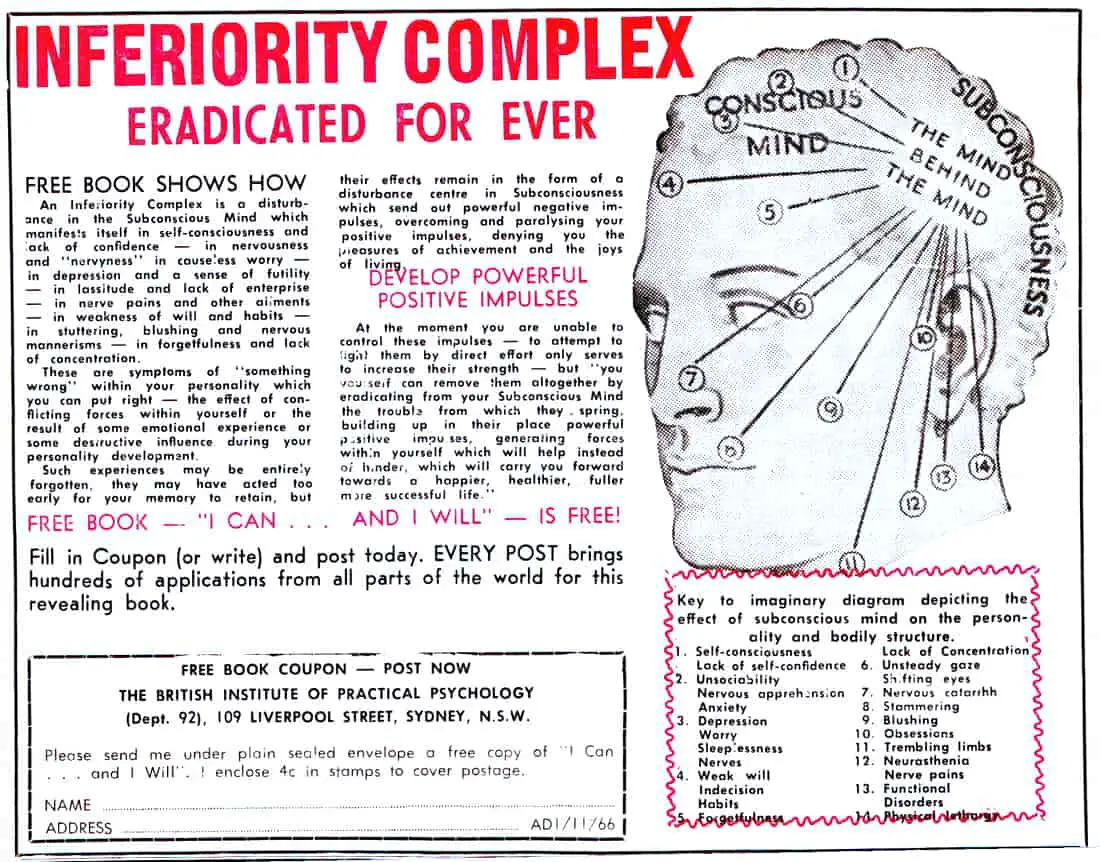

However, if there wasn’t any special attraction, nor did any particular drawbacks present themselves, and therefore there was no reason for the two of us not to get married. The passive personality of this woman in whom I could detect neither freshness nor charm, or anything especially refined, suited me down to the ground. There was no need to affect intellectual leanings in order to win her over, or to worry that she might be comparing me to the preening men who pose in fashion catalogues, and she didn’t get worked up if I happened to be late for one of our meetings. The paunch that started appearing in my mid-twenties, my skinny legs and forearms that steadfastly refused to bulk up in spite of my best efforts, the inferiority complex I used to have about the size of my penls—I could rest assured that I wouldn’t have to fret about such things on her account.

opening to The Vegetarian, a 2016 novel by Han Kang

Like most of the people who work for Marty Butler, Brian dresses neater than a deacon. No long hair or bandit mustaches for the Butler crew. No muttonchop sideburns or flared pants or elevated shoes. Definitely no paisley or tie-dye. Brian Shea dresses like someone from a decade earlier—white T-shirt under a navy blue Baracuta. (The Baracuta jacket—navy blue, tan, or occasionally brown—is a staple of Butler crew guys; they wear it even on days like today, when the mercury approaches 80 at nine a.m. They swap it out in the winter for topcoats or leather car coats with thick wool lining, but come spring they all bring the Baracutas back out of the closet on the same day.) Brian’s cheeks are shaved close, his blond hair cropped tight in a crew cut, and he wears off-white chinos and scuffed black ankle boots with zippers on the sides. Brian has eyes the color of Windex. They sparkle and glint at her with an air of mild presumption, like he knows the things she thinks she keeps hidden. And those things amuse him.

Small Mercies by Dennis Lehane 2023

Jules is tall and sinewy, with long smooth hair the color of an apple. Every inch of her is soft and feminine and waiting on a broken heart the way miners wait on black lung—she just knows it’s coming. She’s fragile, this product of Mary Pat’s womb—fragile in the eyes, fragile in her flesh, fragile in her soul. All the tough talk, the cigarettes, the ability to swear like a sailor and spit like a longshoreman, can’t fully disguise that.

Small Mercies by Dennis Lehane 2023

THE SHOWING AND TELLING COMBO

Writers are often told to ‘show not tell’ but great writers know when to show and when to just sum it up.

Showing:

‘Lockie lay on his bed getting up a sweat, or went out walking around the swampy drains behind the house. He played his Van Halen tapes and stood in front of the mirror with his tennis racquet, giving it vibrato and thrash chords and feedback to forget his troubles.

Lockie Leonard, Human Torpedo by Tim Winton

Telling:

Lockie liked to walk. He also liked music and tennis and tended to get bored.

Lockie Leonard, Human Torpedo by Tim Winton

Showing:

Nan’s view of the physical world was a deeply personal one. And when she wasn’t outside chopping wood or raking leaves, she was observing the weather. Her concern with atmospheric conditions was based on a rather pessimistic view of the frequency of natural

My Place by Sally Morgan

disasters. Even though she avidly listened to weather reports on the radio, she never put her complete faith in any meteorologist’s opinion. Nana knew their predictions weren’t as predictable as her own. Daily, she checked the sky, the clouds, the wind, and on particularly still days, the reactions of our animals. Sometimes, she would sit up half the night, checking on a movement of a particular star, or pondering the meaning of a new colour she’d seen in the sky at sunset.

Telling:

Nan was very connected to nature and took a deep interest in weather reports, animals and stars.

My Place by Sally Morgan

STORIES WHICH ARE PRETTY MUCH ENTIRELY CHARACTER SKETCHES

In New Zealand, one of the NCEA English assessments requires students to describe a character. When teaching high school English in Aotearoa I was on the hunt for short story examples. Since then I’ve found some short stories in which the plot comes secondary to character sketch.

- “Mrs Turner Cutting the Grass” by Carol Shields

- “Reunion” by John Cheever

- “I Live On Your Visits” by Dorothy Parker

FURTHER READING

Some storytellers describe a person as an animal. This is an advanced technique which suits some stories.