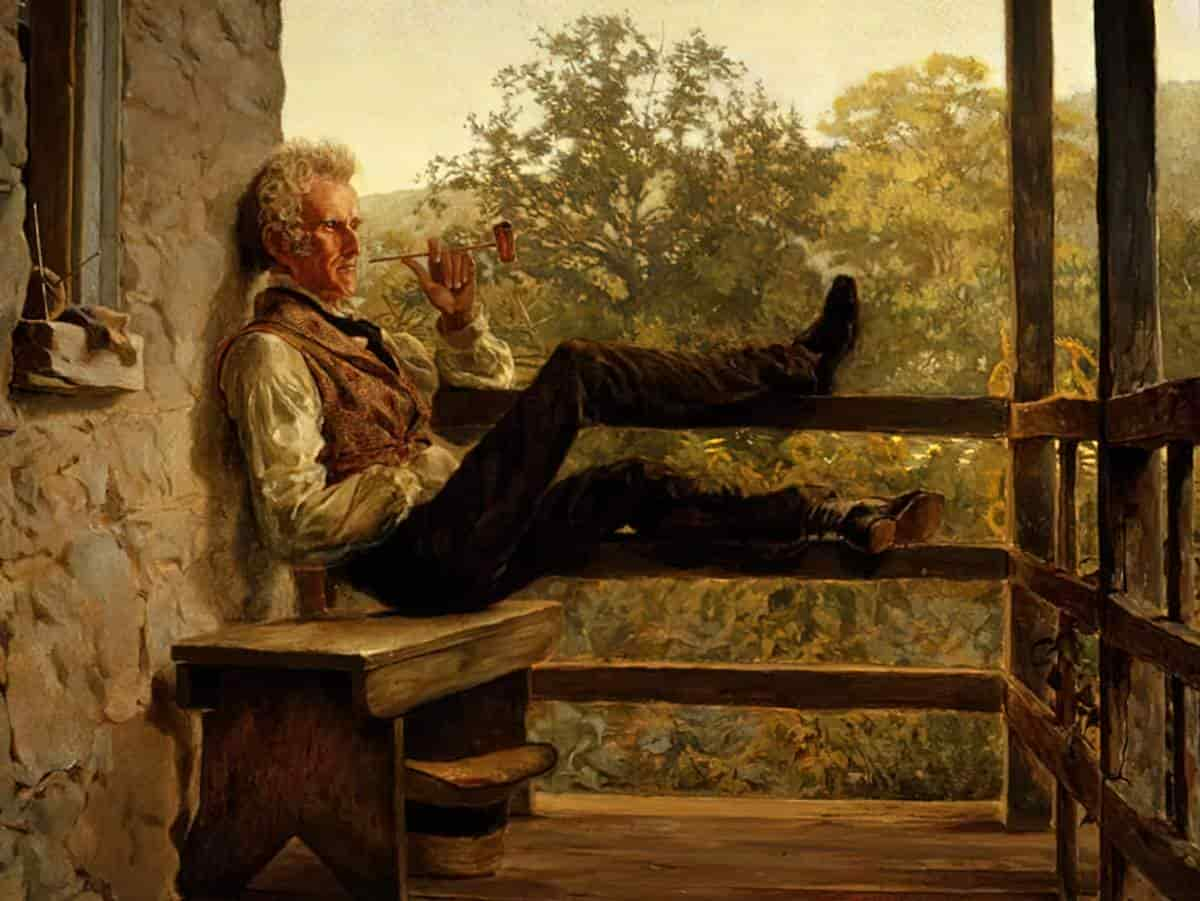

A SOUTHERN AMERICAN PORCH IN SUMMER

People took porches and porch time for granted back then. Everybody had porches; they were nothing special. An outdoor room halfway between the world of the street and the world of the home. If the porch wrapped around the house as the Abbotts’ did, there were different worlds on the front, side, and back porch. If you were laid up on the side porch the way the Ya-Yas were in the picture, you were private, comfortably cloistered. The side porch—that’s where the Ya-Yas went if their hair was in pin curls, when they didn’t want to wave and chat to passersby. This is where they sighed, this is where they dreamed. This is where they lay for hours, contemplating their navels, sweating, dozing, swatting flies, trading secrets there on the porch in a hot, humid girl soup. And in the evening when the sun went down, the fireflies would light up over by the camellias, and that little nimbus of light would lull the Ya-Yas even deeper into porch reveries. Reveries that would linger in their bodies even as they aged.

from Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood by Rebecca Wells

There isn’t much to be said about a porch itself—there’s little furniture, no wall-hangings, and little to distinguish one porch from any other—architecturally. So the author writes about all the people who inhabit the porch, and evokes an atmosphere via character memories.

A LARGE 1950s ENGLISH COUNTRY MANSION WITH ITS BEST TIMES BEHIND IT

I had in the meantime more opportunity to observe the house; it was taller than it was broad, comprising four floors, with ivy covering much of the front right up to the gables. I could see from its windows, however, that at least half of it was dust-sheeted.

Kazuo Ishiguro, The Remains of the Day

A HOUSE IN MONTANA ON DUSK

The novel opens via the viewpoint character of a wolf, who starts in the forest then happens upon a house, taking the reader into civilisation. Wolves would not be able to describe a house in the following way, but a few details suggest a wolfish, and therefore forbidding, lens.

Notice too how Sparks takes the ‘camera’ from the porch to the inside, led by the cry of the baby, through the veil of curtains.

[The small ranch house] had been built on elevated ground above the bend of a creek whose bends bristled with willow and chokecherry. There were barns to one side and white-fenced corals. The house itself was a clapboard, freshly painted a deep oxblood. Along its southern side ran a porch that now, as the sun elbowed into the mountains, was bathed in a last glow of golden light. The windows along the porch had been opened wide and net curtains stirred in what passed for a breeze.

From somewhere inside floated the babble of a radio and maybe it was this that made it hard for whoever was at home to hear the crying of the baby. The dark blue buggy on the porch rocked a little and a pair of pink arms stretched craving for attention from its rim. But no one came. And at last, distracted by the play of sunlight on his hands and forearms, the baby gave up and began to coo instead.

The only one who heard was the wolf.

The Loop, Nicholas Evans

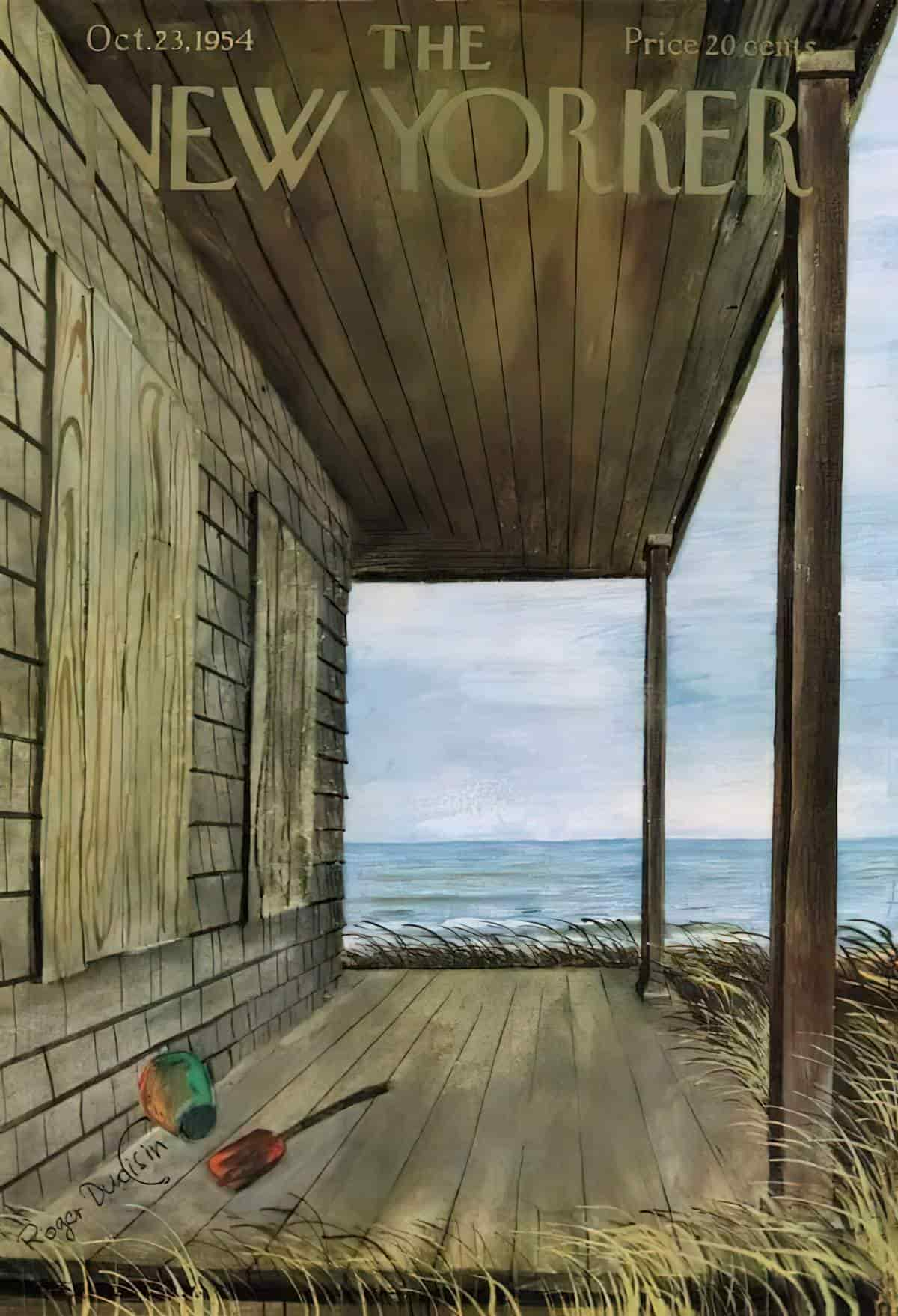

A RUSTIC CAPE COD COMPOUND IN SUMMER

Notice how the following opens with a list, fragments of memory, leading into a more solid description of a house, a porch, the natural surrounds. This order—from tiny detail to long shot—is the inverse of what we usually see in film and storytelling (‘establishing shot’ zooming in on closer and closer detail):

Today. August 1, the Back Woods.

6:30 a.m.

Things come from nowhere. The mind is empty and then, inside the frame, a pear. Perfect, green, the stem atilt, a single leaf. It sits in a white ironstone bowl, nestled among the limes, in the center of a weathered picnic table, on an old screen porch, at the edge of a pond, deep in the woods, beside the sea. Next to the bowl is a brass candlestick covered in drips of cold wax and the ingrained dust of a long winter left on an open shelf. Half-eaten plates of pasta, an unfolded linen napkin, dregs of claret in a wine bottle, a breadboard, handmade, rough-hewn, the bread torn not sliced. A mildewed book of poetry lies open on the table. “To a Skylark,” soaring into the blue-painful, thrilling-replays in my mind as I stare at the still life of last night’s dinner. “The world should listen then, as I am listening now.” He read it so beautifully. “For Anna.” And we all sat there, spellbound, remembering her. I could look at him and nothing else for eternity and be happy. I could listen to him, my eyes closed, feel his breath and his words wash over me, time and time and time again. It is all I want.Beyond the edge of the table, the light dims as it passes through the screens before brightening over the dappled trees, the pure blue of the pond, the deep-black shadows of the tupelos at the water’s edge where the reach of the sun falters this early in the day. I ponder a quarter-inch of thick, stale espresso in a dirty cup and consider drinking it. The air is raw. I shiver under the faded lavender bathrobe-my mother’s-that I put on every summer when we return to the camp. It smells of her, and of dormancy tinged with mouse droppings. This is my favorite hour in the Back Woods. Early morning on the pond before anyone else is awake. The sunlight clear, flinty, the water bracing, the whippoorwills finally quiet.

Outside the porch door, on the small wooden deck, sand has built up between the slats-it needs to be swept. A broom leans against the screen, indenting it, but I ignore it and head down the little path that leads to our beach. Behind me, the door hinges shriek in resistance.

I drop my bathrobe to the ground and stand naked at the water’s edge. On the far side of the pond, beyond the break of pine and shrub oak, the ocean is furious, roaring. It must be carrying a storm in its belly from somewhere out at sea. But here, at the edge of the pond, the air is honey-still.

the opening to The Paper Palace, a 2022 novel by Miranda Cowley Heller

A COUNTRY ESTATE IN 1948 KYOTO

Prelude

Kyoto Prefecture, Japan

Summer 1948

The first real memory Nori had was pulling up to that house. For many years afterward, she would try to stretch the boundaries of her mind further, to what came before that day. Time and time again, she’d lie on her back in the stillness of the night and try to recall. Sometimes she’d catch a glimpse in her head of a tiny apartment with lurid yellow walls. But the image would disappear as quickly as it came, leaving no sense of satisfaction in its wake. And so if you asked her, Nori would say that her life had officially begun the day she laid eyes on the imposing estate that rested serenely between the crests of two green hills. It was a stunningly beautiful place—there was no denying it—and yet, despite this beauty, Nori felt her stomach clench and her gut churn at the sight of it. Her mother rarely took her anywhere, and somehow she knew that something was waiting for her there that she would not like.

The faded blue automobile skidded to a stop on the street across from the estate. It was in the traditional style, surrounded by high white walls. The first set of gates was open, allowing full view into the meticulously arranged courtyard beyond. But the inner gates to the house itself were sealed shut. There were words engraved at the top of the main gate, embossed in gold lettering for all to see. But Nori could not read them. She could read and write her name—No‑ri‑ko—but nothing else. In that moment, she wished she could read every word ever written, in every language from sea to sea. Not being able to read those letters frustrated her to an extent she didn’t understand. She turned to her mother.“Okaasan, what do those letters say?”

the opening to Fifty Words for Rain by Asha Lemmie (2021)

THE HOUSE OF YOUR DEAD MOTHER (AND LIVING SISTER) IN 1960S SMALLTOWN ONTARIO

Below we have another example of a woman pulling up outside a house.

You’ve just arrived in town after driving all the way from Toronto. The mother who always lived here is dead. Your sister, who looked after her during a long illness, is at work.

The red brick of which the house is built looked harsh and hot in the sun and was marked in two or three places by long grimacing cracks; the verandah, which always had the air of an insubstantial decoration, was visibly falling away. There was—there is—a little blind window of coloured glass beside the front door. I sat staring at it with a puzzled lack of emotional recognition. I sat and looked at the house and the window shades did not move, the door did not fly open, no one came out on the verandah; there was no one at home. This was what I expected, since Maddy works now in the office of the town clerk, yet I was surprised to see the house take on such a closed, bare, impoverished look, merely by being left empty.

“The Peace of Utrecht” by Alice Munro (1968)

Notice how what and who is not there is equally significant as who what is. When writers tell us what is not, they are slowing the pacing down to a pause. For the character, the image feels suspended in time.

A HOUSE IN RURAL AUSTRALIA

Think about how you (or your character) feels approaching the house.

The simile below tells us exactly how the main character feels approaching this house after a party invitation:

The Duncans’ house is a brutal cube of concrete set high on the grassy headland. On a sunny day the light glares off its bone-white walls but when the sky is overcast the cube looks drab, like an exposed bunker where at any moment the long grey barrel of a field gun might be wheeled out onto the terrace.

The Labyrinth by Amanda Lohrey

When Erica gets to the house, the vision changes again. This passage serves as a reminder that when describing a space, it’s often a good idea to describe the light (or lighting):

The massive double doors of the Duncan cube give the house the air of a fortress. Ten feet tall and painted a bright blue, they open into a wide courtyard with a white pebbled floor and lime-washed walls. Along the walls are huge terracotta urns with lemon trees and in the centre of the courtyard flames are leaping from a cast-iron brazier. The courtyard is full of people, mostly middle-aged, all of them lit by a strobe light that emanates from the northern wall of the courtyard, a rectangular grotto where the red bulbs have been installed in the shape of a cross that pulsates with a gory neon yellow.

The Labyrinth by Amanda Lohrey

WRITE YOUR OWN

Header illustration: Erik Blegvad (1923-2014) Dusty and the Fiddlers by Miska Miles.