When conveying the movement of the vehicle, Lists and Repetition as Storytelling Technique may come in handy.

Now on the streetcar going to Lena’s place I couldn’t stop the stupidity. I said, “Are we still downtown?’”The high buildings had been quickly left behind but I didn’t think you could call this area residential. The same thing went on over and over again – a dry cleaner, a florist, a grocery store, a restaurant. Boxes of fruit and vegetables out on the sidewalk, signs for dentists and dressmakers and plumbing suppliers in the second-storey windows. Hardly a building higher than that, hardly a tree.

“Queenie” by Alice Munro

Mansfield creates an almost magical, fantasy London in the paragraph below, as Rosabel looks out of the window of a bus on a rainy London evening, after a day working in a hat shop, selling fancy goods to rich ladies. For now she takes some of the shine of richness home with her:

Rosabel looked out of the windows; the street was blurred and misty, but light striking on the panes turned their dullness to opal and silver, and the jewellers’ shops seen through this, were fairy palaces. Her feet were horribly wet, and she knew the bottom of her skirt and petticoat would be coated with black, greasy mud. There was a sickening smell of warm humanity—it seemed to be oozing out of everybody in the ‘bus—and everybody had the same expression, sitting so still, staring in front of them. How many times had she read these advertisements—”Sapolio Saves Time, Saves Labour”—”Heinz’s Tomato Sauce”—and the inane, annoying dialogue between doctor and judge concerning the superlative merits of “Lamplough’s Pyretic Saline.”

“The Tiredness of Rosabel” by Katherine Mansfield (Read online for free at Project Gutenberg.)

Mansfield wrote a number of train scenes in her stories. Below we have a man who is fully at home in his work, fully at home on a first-class smoker carriage, but who carries the backpack of privilege with him despite his discomfort in life. Mansfield conveys William’s ignorance about his own privilege by showing us his judgements of the people he sees on the train platform as the train starts moving. She uses a paragraph break to tell us we have left the city and entered the country around London.

Two men came in, stepped across him, and made for the farther corner. A young fellow swung his golf clubs into the rack and sat down opposite. The train gave a gentle lurch, they were off. William glanced up and saw the hot, bright station slipping away. A red-faced girl raced along by the carriages, there was something strained and almost desperate in the way she waved and called. “Hysterical!” thought William dully. Then a greasy, black-faced workman at the end of the platform grinned at the passing train. And William thought, “A filthy life!” and went back to his papers.

When he looked up again there were fields, and beasts standing for shelter under the dark trees. A wide river, with naked children splashing in the shallows, glided into sight and was gone again. The sky shone pale, and one bird drifted high like a dark fleck in a jewel.

“Marriage a la Mode” by Katherine Mansfield

and on the way back to London, gripped with further anxiety:

Fields, trees, hedges streamed by. They shook through the empty, blind-looking little town, ground up the steep pull to the station.

“Marriage a la Mode” by Katherine Mansfield

Escape

The first time—which would become legend among them—they entered in darkness. Night enfolded the sand dunes. Stars clamored around a meager slice of moon.

They would find nothing in Cabo Polonio, the cart driver said: no electricity, and no running water. The cart driver lived in a nearby village but made that trip twice a week to supply the little grocery store that served the lighthouse keeper and a few scattered fishermen. There was no road in; you had to know your way. It was lonely out there, he remarked, glancing at them sideways, smiling to bare his remaining teeth, hinting, though he stopped short of asking any questions about what they were doing, why they were traveling to this of all places, just the five of them, without a man, and it was just as well because they wouldn’t have had a decent answer. The trees gradually receded, but clumps of brush still reared their tousled heads from the smooth slopes as if just being born. The horse-drawn cart moved slowly, methodically, creaking with the weight of them, hoofs muffled in the loose sand. They were stunned by the sand dunes, the vast life of them. Each traveler became lost in her own thoughts. Their five-hour bus ride down the highway already seemed a distant memory, dislodged from this place, like a dream from which they’d now awakened. The dunes rippled out around them, a spare landscape, the landscape of another planet, as if in leaving Montevideo they’d also managed to leave Earth, like that rocket that some years ago had taken men to the moon, only they were not men, and this was not the moon, it was something else, they were something else, uncharted by astronomers. The lighthouse rose before them, with its slowly circling light. They approached the cape along a beach, the ocean to their right, shimmering in the dark, in constant conversation with the sand. The cart passed a few small, boxlike huts, fishermen’s huts, black against the black sky. They descended from the cart, paid the driver, and carried their packs stuffed with food and clothes and blankets as they wandered around, staring into the night. The ocean surrounded them on three sides of this cape, this almost-island, a thumb extending off the hand of the known world.

from the opening of Cantoras, a 2020 novel by Carolina De Robertis

June 12, 1954—The drive from Salina to Morgen was three hours, and for much of it, Emmett hadn’t said a word. For the first sixty miles or so, Warden Williams had made an effort at friendly conversation. He had told a few stories about his childhood back East and asked a few questions about Emmett’s on the farm. But this was the last they’d be together, and Emmett didn’t see much sense in going into all of that now. So when they crossed the border from Kansas into Nebraska and the warden turned on the radio, Emmett stared out the window at the prairie, keeping his thoughts to himself.

When they were five miles south of town, Emmett pointed through the windshield.

—You take that next right. It’ll be the white house about four miles down the road.

The warden slowed his car and took the turn. They drove past the McKusker place, then the Andersens’ with its matching pair of large red barns. A few minutes later they could see Emmett’s house standing beside a small grove of oak trees about thirty yards from the road. To Emmett, all the houses in this part of the country looked like they’d been dropped from the sky. The Watson house just looked like it’d had a rougher landing. The roof line sagged on either side of the chimney and the window frames were slanted just enough that half the windows wouldn’t quite open and the other half wouldn’t quite shut. In another moment, they’d be able to see how the paint had been shaken right off the clapboard. But when they got within a hundred feet of the driveway, the warden pulled to the side of the road.

—Emmett, he said, with his hands on the wheel, before we drive in there’s something I’d like to say.

the opening to The Lincoln Highway, a 2023 historical novel by Amor Towles

The night feels shredded as I leave the city, through perforated mist, a crumbling September sky. Behind me, Potrero Hill is a stretch of dead beach, all of San Francisco unconscious or oblivious. Above the cloud line, an eerie yellow sphere is rising. It’s the moon, gigantic and overstuffed, the color of lemonade. I can’t stop watching it roll higher and higher, saturated with brightness, like a wound. Or like a door lit entirely by pain.

No one is coming to save me. No one can save anyone, though once I believed differently. I believed all sorts of things, but now I see the only way forward is to begin with nothing, or whatever is less than nothing. I have myself and no one else. I have the road and the snaking mist. I have this tortured moon.

I drive until I stop seeing familiar landmarks, stop looking in my rearview to see if someone is following me.

the opening to When the Stars Go Dark, a 2022 novel by Paula McLain

Lyle asked how the hell we were going to fit in that and she said, Oh yeah. So there we were, cruising around in a yellow car with a green stripe that ran up the hood and a weird door, the dash lights all burned out and windows poorly tinted and not even a rearview or a driver’s-side mirror for Lyle to see if a cop was behind us. I sat in the back seat with June, the two of us crunched in together, thigh to thigh, which had been part of my foolproof plan. June was leaning away from me, and I had one arm along the back of the seat and was leaning toward her, just enough that I could see out the windshield. We went down Main, the string of yellow lights that ran along the edges of the marquee of the old theatre still lit up. We hit the end of downtown and turned and crossed the tracks and it was clear that whoever could afford to live where they wanted did not live on this side of town. There were fewer street lights or maybe there was more distance between the lights because the blocks were longer, I don’t know, and there were more cars parked on the streets than where Lyle and Cindy lived, which was across town and up the hill.

Everything good is always up on the hill. Down below things get crowded. This

from The New Yorker short story “False Star” by Sterling Hollywhitemountain, March 30, 2023.

is where I’d live if I lived here, June said. Typical indin, Lyle said. I had never been drunk after buying a car so I told June she looked beautiful and she smiled and I was so surprised by this that I could not say anything more. For years after that I thought about why she had smiled and eventually concluded what many people do about such matters, which is that most things are not worth dwelling on.

At half-past ten a bus goes through the town, not slowing much; we see it go by at the end of our street. It is the same bus I used to take when I came home from college, and I remember coming into Jubilee on some warm night, seeing the earth bare around the massive roots of the trees, the dirnking fountain surrounded by little puddles of water on the main street, the soft scrawls of blue and red and orange light that said BILLIARDS and CAFE; feeling as I recognized these signs a queer kind of oppression and release, as I exchanged the whole holiday world of school, of friends and, later on, of love, for the dim world of continuing disaster, of home.

“The Peace of Utrecht” by Alice Munro (1968)

A SMALL ITALIAN TOURIST TOWN OFF THE BEATEN TRACK

As we rounded the bend and descended from the plateau, he gestured toward Valetto, at his unlikely birthplace barnacled to a spur of rock in the middle of a valley of canyons. From a distance, the town is a faint, medieval silhouette atop a pinnacle, set against the haze of distant hill towns, their fields and slopes and church spires arranged around the edges of a blue bowl. But then, as you get closer, the colours come into relief—the pale umber walls, the surrounding moonscape of chalk-white canyons and escarpments, the fringe of chestnut and olive groves at the base of its cliffs. Still closer, it becomes a diorama of windows and terracotta roof tiles. In my mind, the twelfth-century campanile of the church—towering high above the other rooflines—has always resembled an obelisk of some ancient civilization, a primitive, tapering monument to fickle and vengeful gods. The skyline is beautiful but also desolate and otherworldly. It comes at you by degrees, as you descend the hill, and then suddenly you’re a diver coming upon the hulk of some ravaged galleon at the bottom of the sea.

Return to Valetto by Dominic Smith

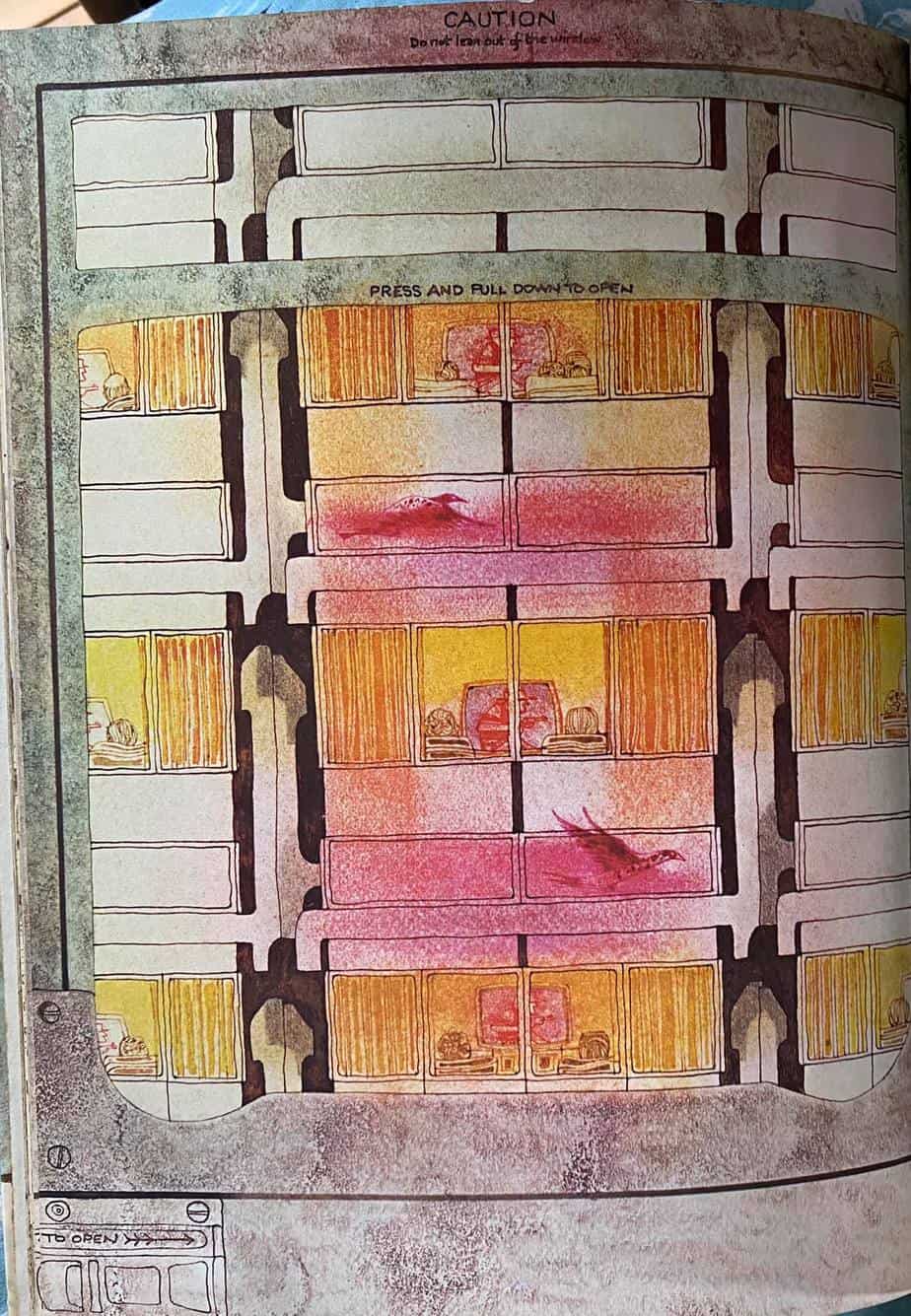

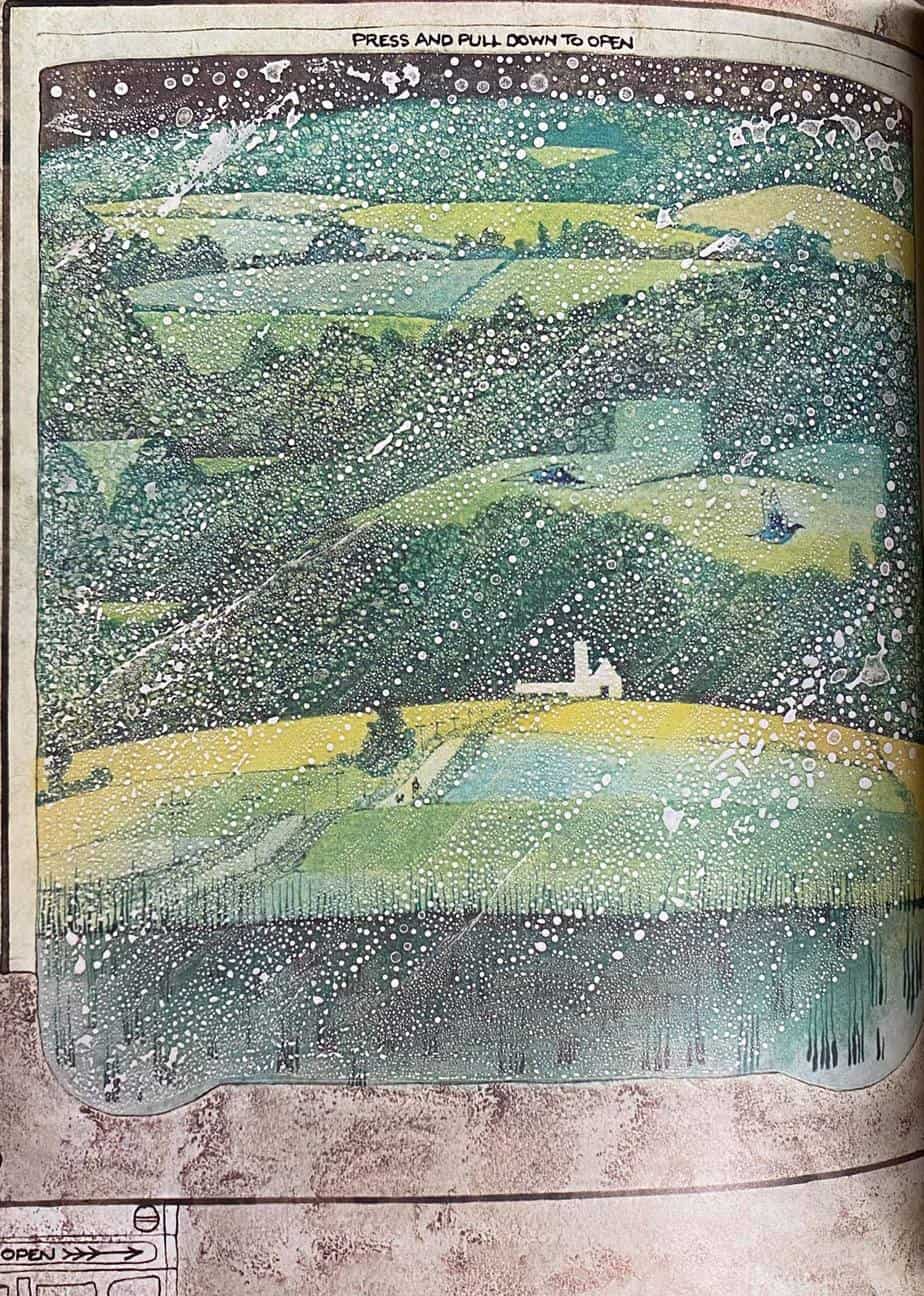

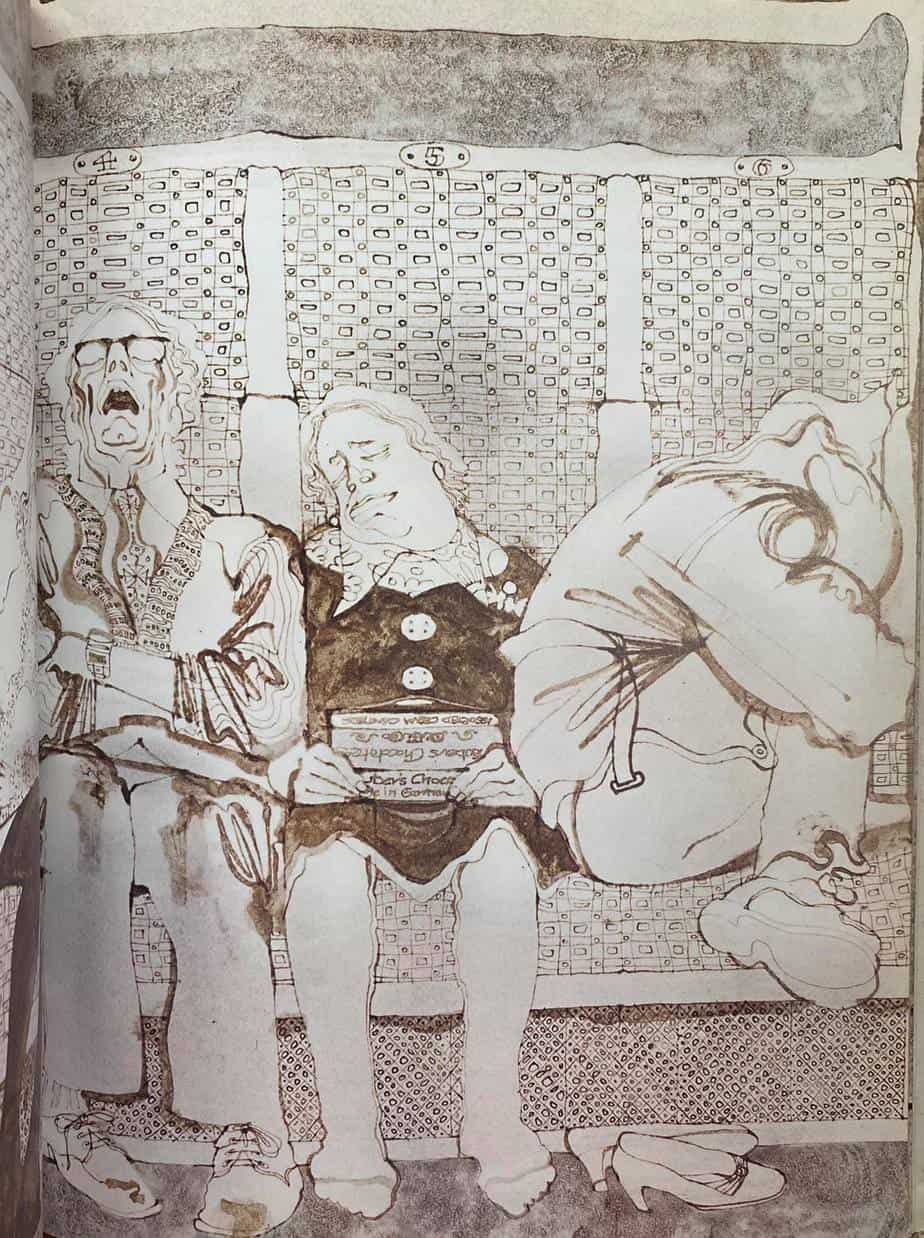

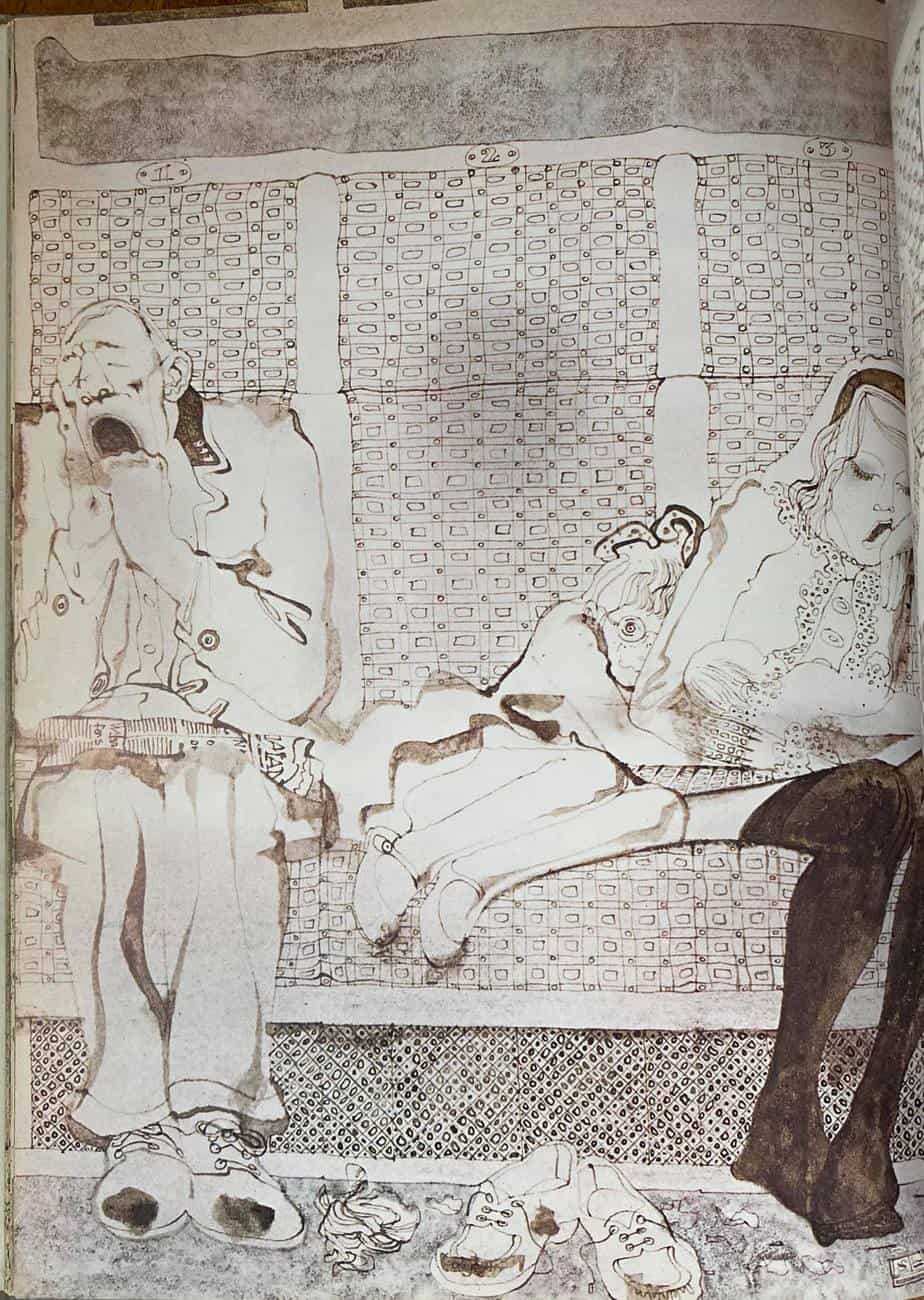

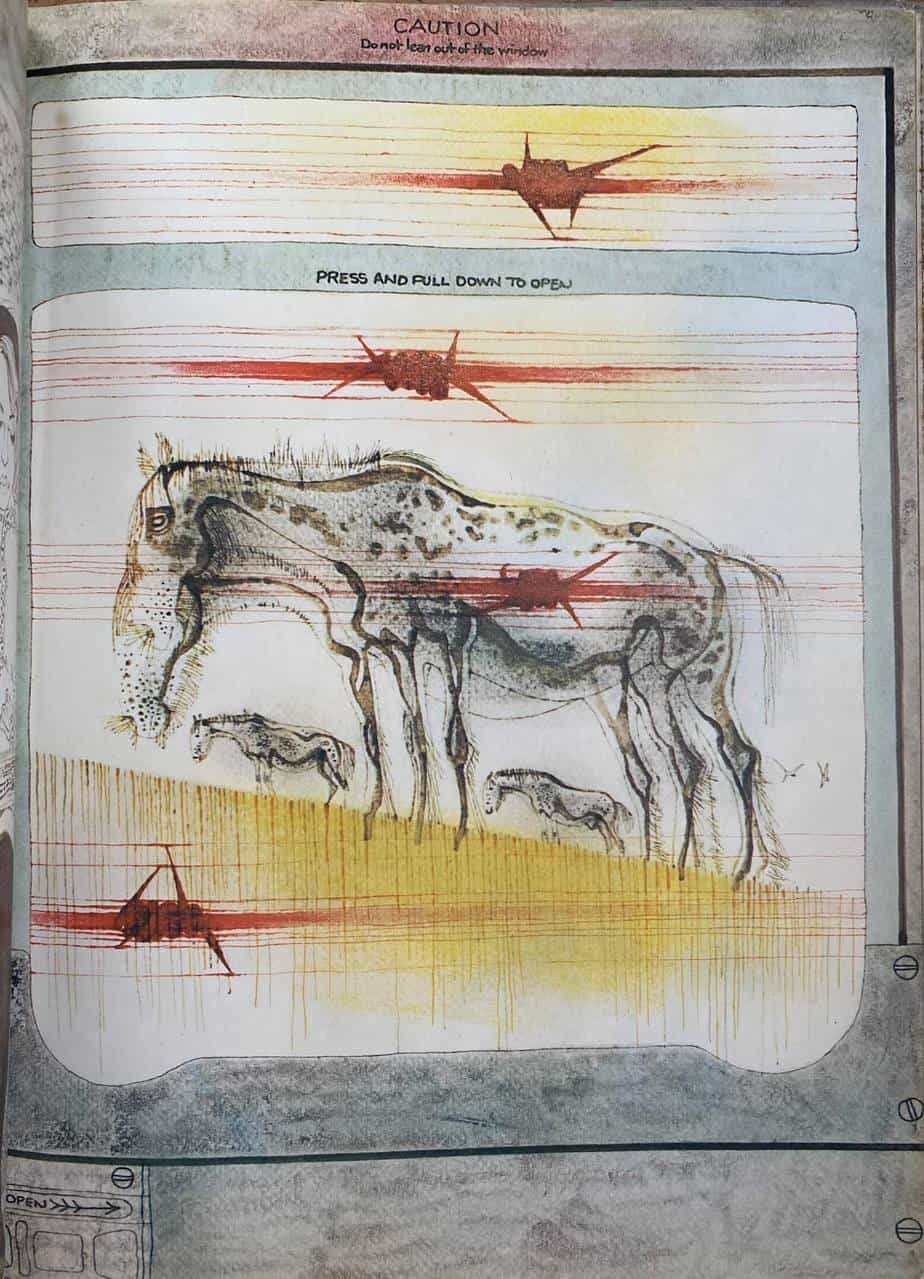

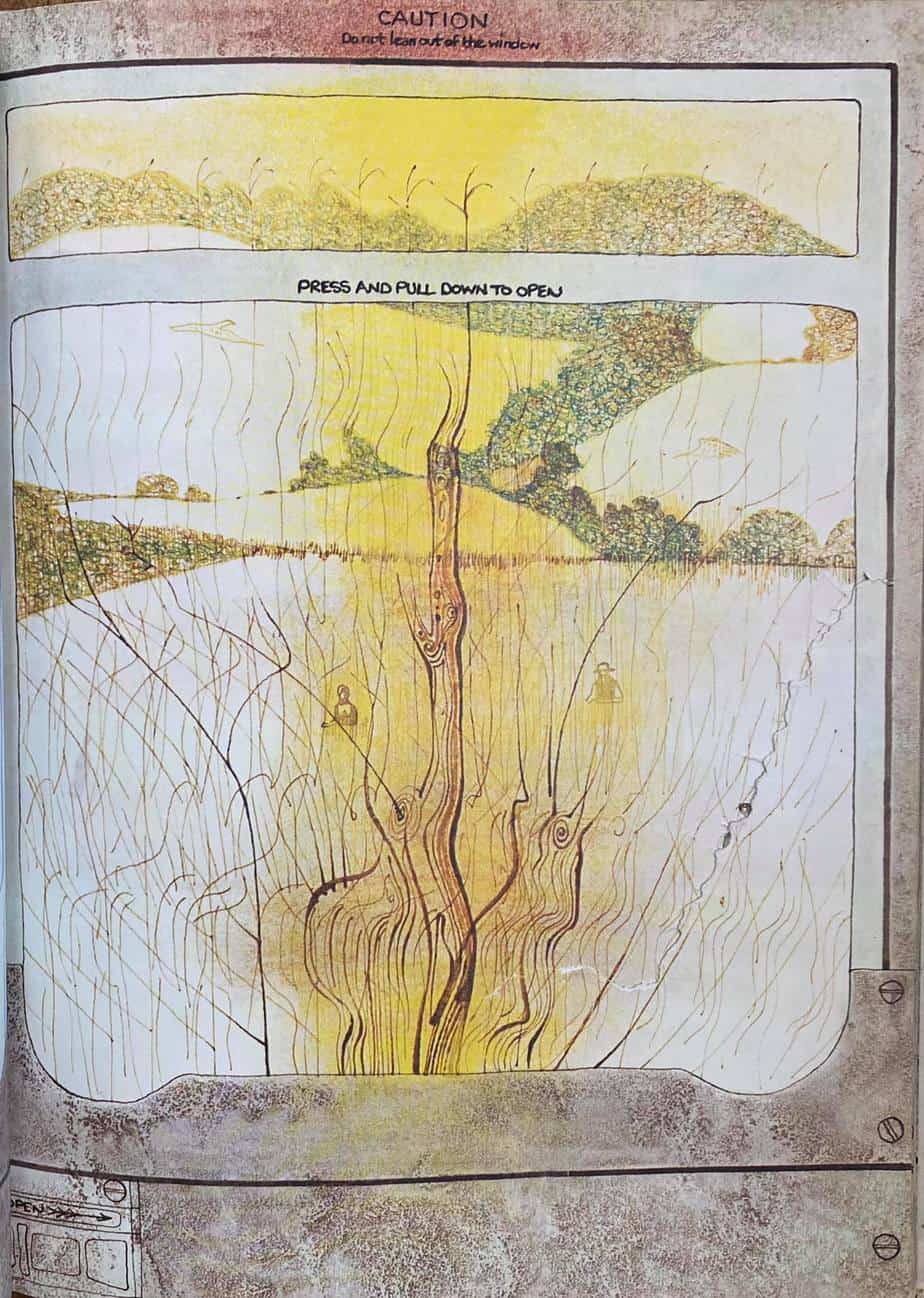

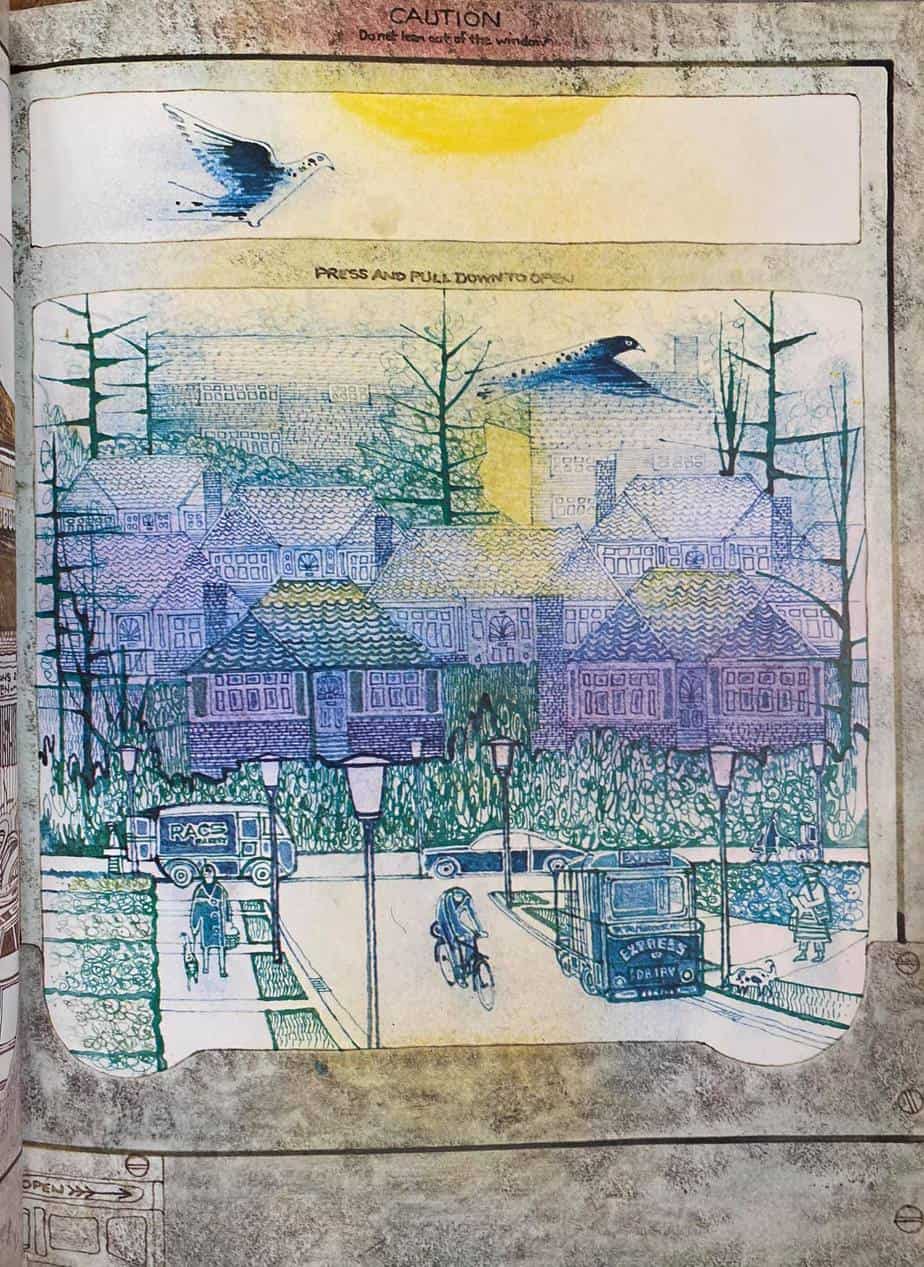

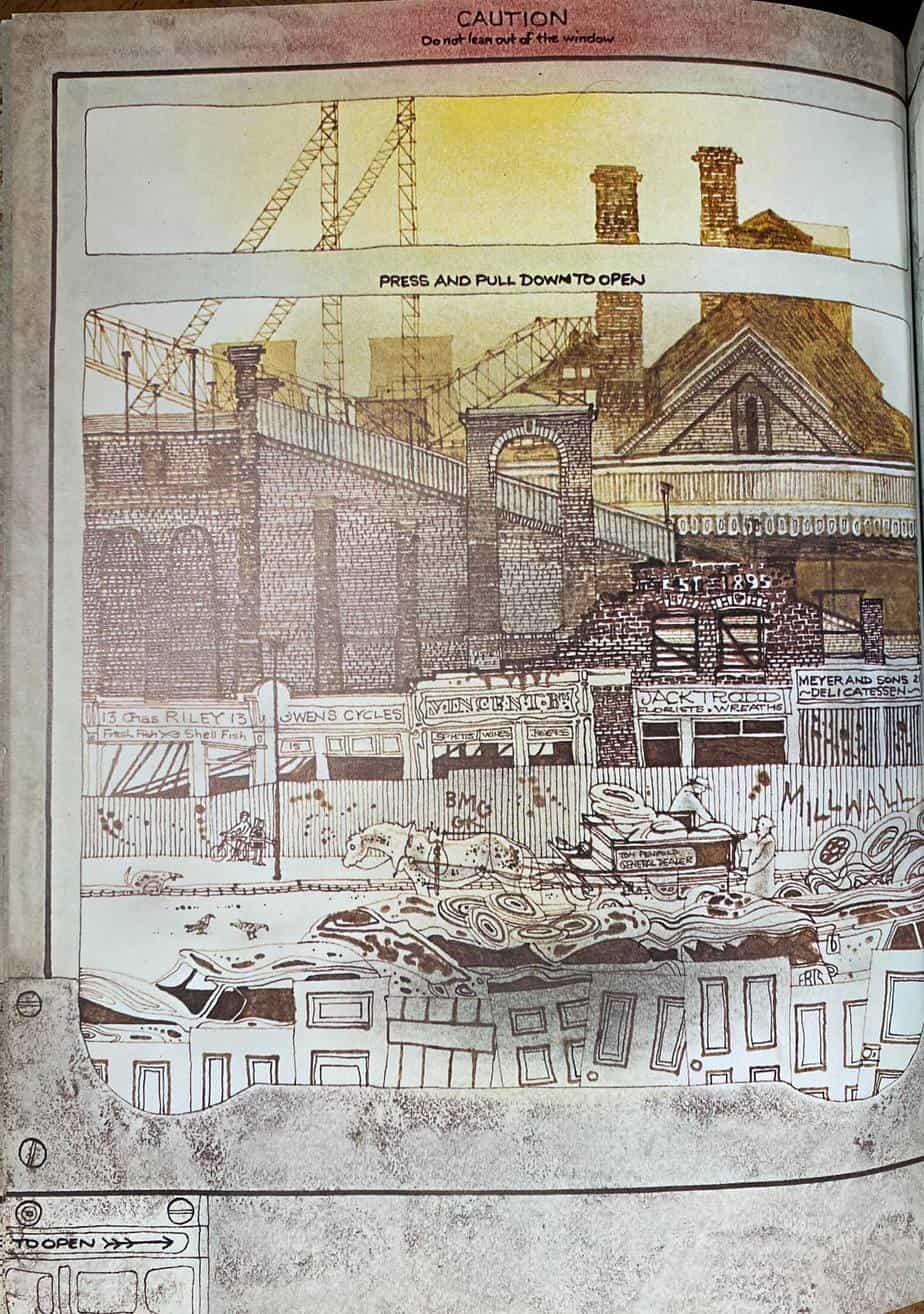

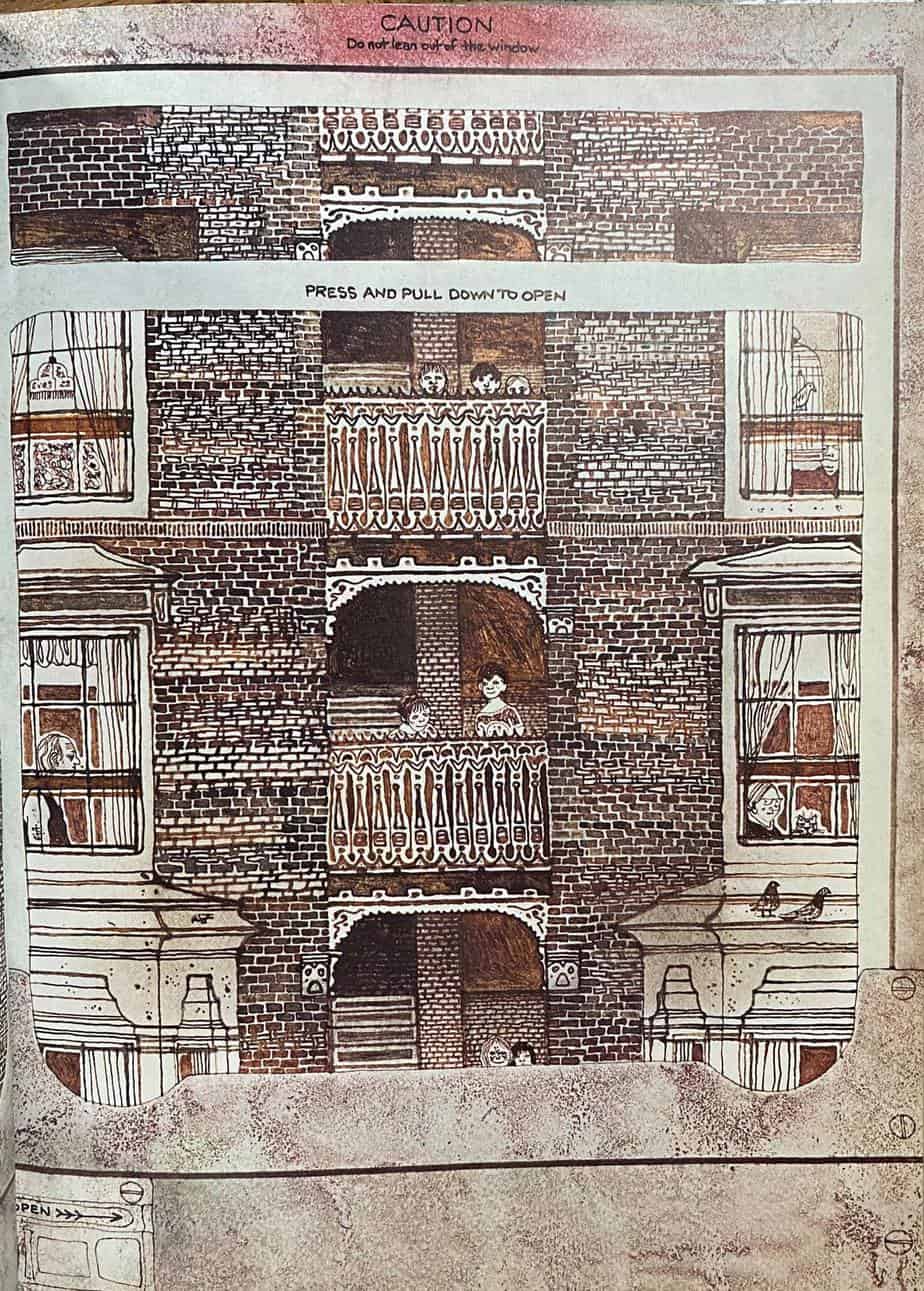

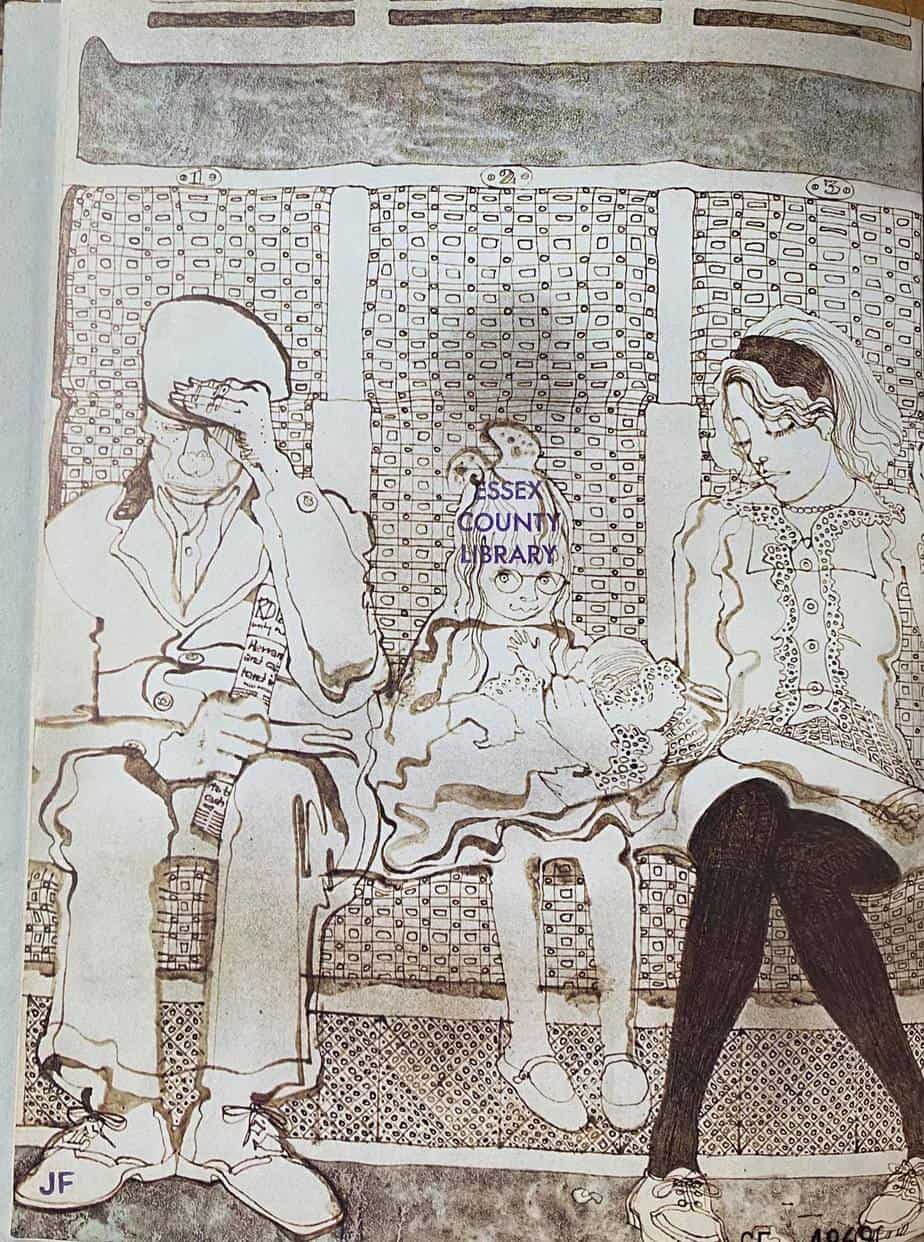

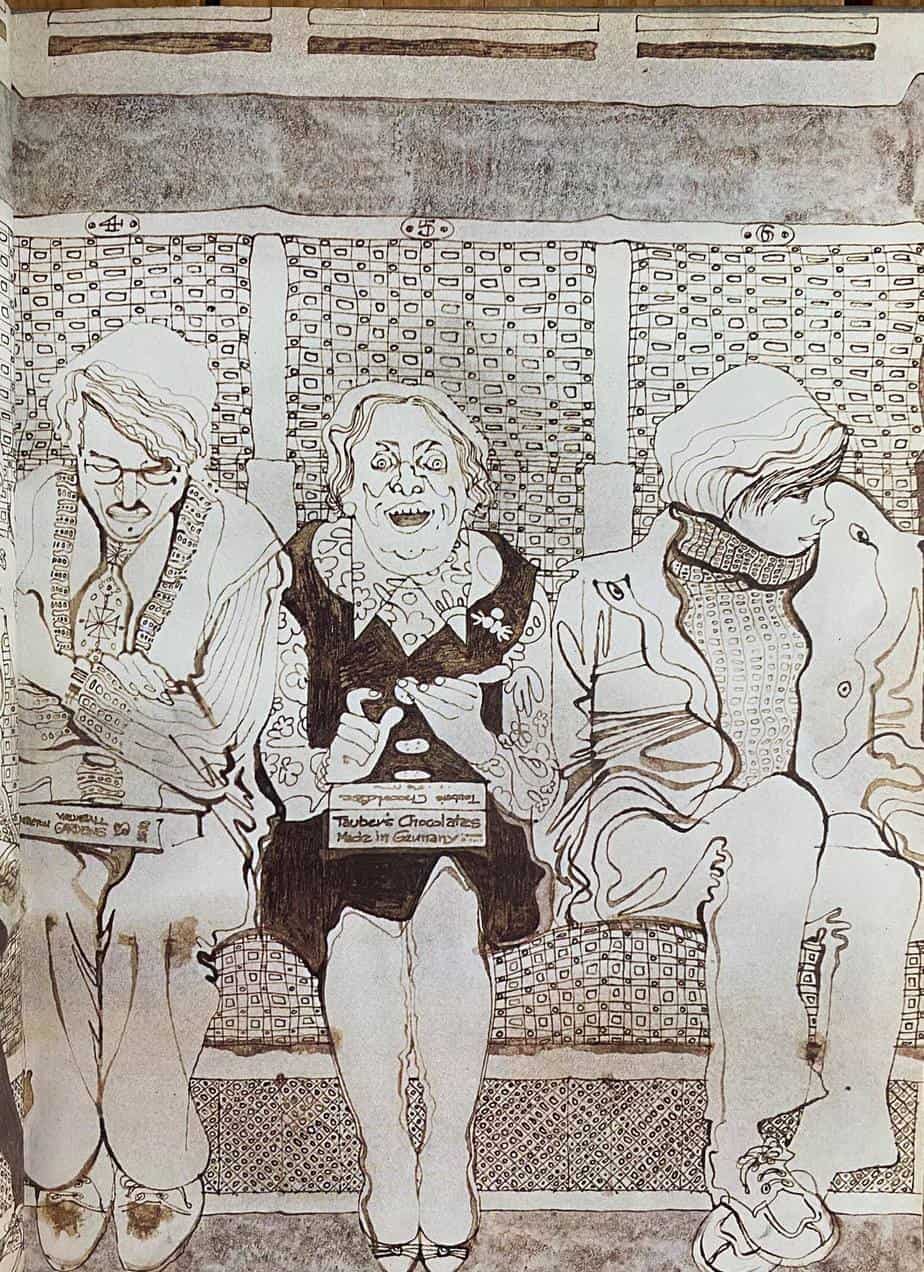

Charles Keeping : ‘Inter City’ 1977. Inter city was the name given to the train service in Britain during the 1970s. Apart from getting on/off and a few in the carriages, this picture book is framed as if your looking out of the window as the train leaves London. The train travels through the suburbs, then through the countryside.

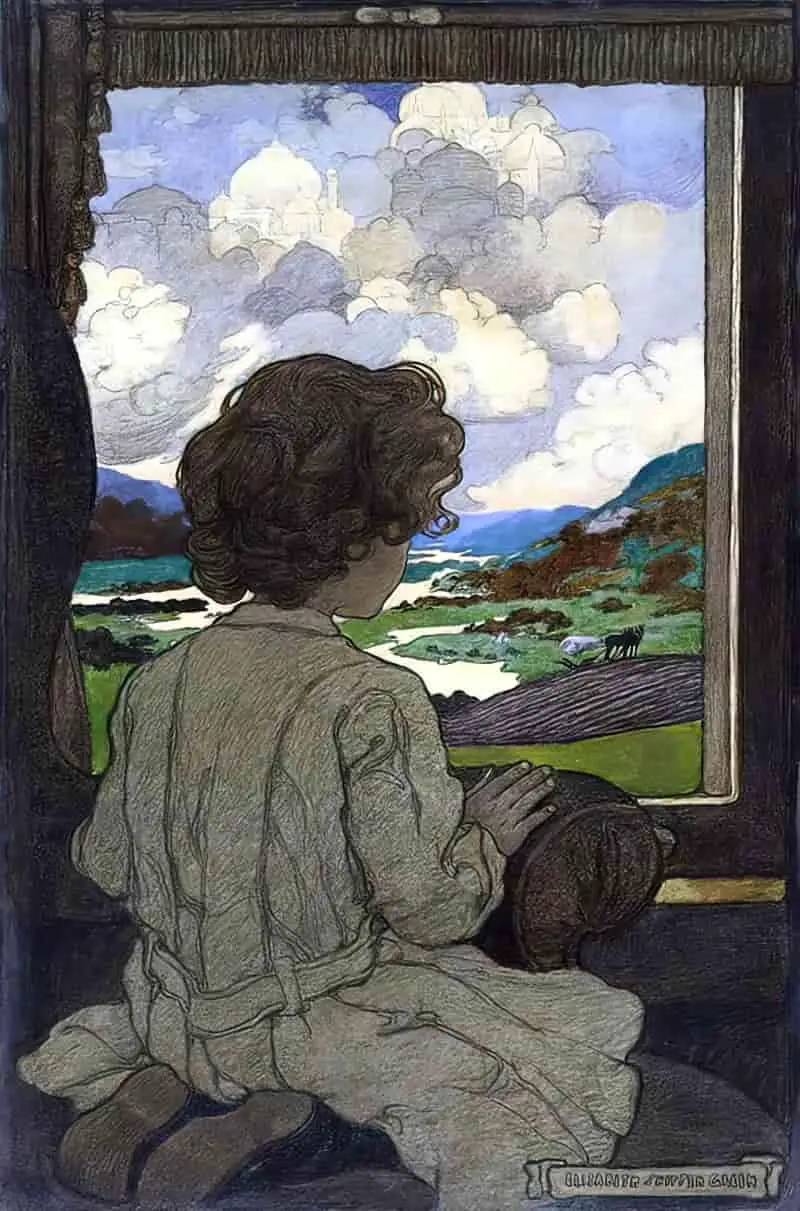

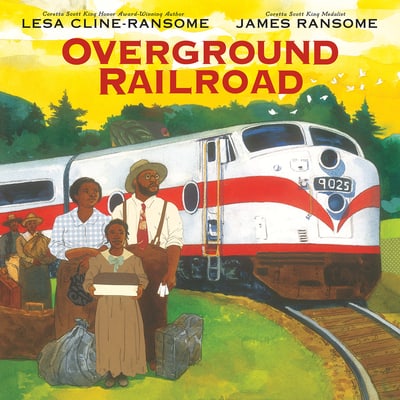

A window into a child’s experience of the Great Migration from the award-winning creators of Before She Was Harriet and Finding Langston .

As she climbs aboard the New York bound Silver Meteor train, Ruth Ellen embarks upon a journey toward a new life up North– one she can’t begin to imagine. Stop by stop, the perceptive young narrator tells her journey in poems, leaving behind the cotton fields and distant Blue Ridge mountains.

Each leg of the trip brings new revelations as scenes out the window of folks working in fields give way to the Delaware River, the curtain that separates the colored car is removed, and glimpses of the freedom and opportunity the family hopes to find come into view. As they travel, Ruth Ellen reads from Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, reflecting on how her journey mirrors her own– until finally the train arrives at its last stop, New York’s Penn Station, and the family heads out into a night filled with bright lights, glimmering stars, and new possibility.

James Ransome’s mixed-media illustrations are full of bold color and texture, bringing Ruth Ellen’s journey to life, from sprawling cotton fields to cramped train cars, the wary glances of other passengers and the dark forest through which Frederick Douglass traveled towards freedom. Overground Railroad is, as Lesa notes, a story “of people who were running from and running to at the same time,” and it’s a story that will stay with readers long after the final pages.