In a previous post I wrote about how to make a character likeable. This is basically an expansion on that post, because when you’re writing an unlikeable character, you’re using the exact same tricks, except more of them. Then, when you’ve exhausted your toolkit, your morally repugnant character can get on with the job of being morally repugnant, and readers will follow, intrigued.

A few quick thoughts on “unlikeable characters”. Often I’ll hear people saying they got feedback their character was unlikeable, so they try to make him/her (usually a her) “nicer.” You do NOT need to make your “unlikeable” character nice! You *might* want to make them more relatable/sympathetic. Important difference. If a character is mean as a snake but has sympathetic backstory &/or relatable motivation, readers will invest in them. (Ex: Snape!) Layering an “unlikeable” character’s interiority to show vulnerability can also help us relate. Some “unlikeable” characters are merely determined/motivated in a way/place society deems inappropriate. (Ie strong girls.) In which case… My advice is usually: don’t compromise a strong girl character *just* to make her “nice” for readers. Those aren’t your readers anyway. But if your strong girl character feels unrelatable (different from “not nice!”) think about adding vulnerability or sympathetic motivation.

Ways to make “unlikeable” characters more relatable:

-Sympathetic backstory

-Vulnerability

-Relatable motivation

NOT by making them “nicer”

“Nice” characters typically annoy and/or bore me anyway as a reader. I want motivated! I want determined! Not nice. At least not in fiction.

@NaomiHughesYA

We do need to know how to write likeable characters before we can write unlikeable ones. All the writers who’ve written super popular antiheroes spent years writing likeable characters first. It’s like how you can’t be a good cartoonist until you’ve mastered life drawing.

Surround unlikeable characters with characters who love them.

A classic example of this is Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With The Wind, who for some reason, hasn’t driven everyone away. If the other characters don’t mind her, we think as readers, she must be all right deep down, and we persevere through the story.

Scarlett O’Hara, the beautiful, spoiled daughter of a well-to-do Georgia plantation owner, must use every means at her disposal to claw her way out of the poverty she finds herself in after Sherman’s March to the Sea.

If the hero is unlikeable, at least make them super competent.

A main character’s unlike-ability is almost completely cancelled out if they are very good at what they do.

Unfortunately for women in real life, this doesn’t apply to female characters quite so much. Compare and contrast Skyler and Walter White. Both are super good at what they do, but one of these characters was vilified by a bulk of the audience. The other was celebrated. I even got talking about TV in a doctor’s waiting room with a man who earnestly and passionately argued his case that Walt should’ve murdered Skyler to get rid of her early on. To him that would’ve made a better, more satisfying TV show.

From Steve Jobs, who was a petulant, entitled asshole who bullied employees and nearly destroyed his own company because of his immaturity…from his father he was taught that even the back of the cabinets – the parts people never saw – still mattered. Being a craftsman means caring about every part of what you do, not just the visible or superficial parts.

Great Lessons From Bad People

Make sure the audience understands motivation.

Okay, backtracking a little, first they have to be motivated. They have to be active, not passive. They have to have a solid desire and plan to get it. Same as all good characters.

Even heroes who are totally likeable in the beginning often begins to act immorally—to do unlikable things—as they begin to lose to the opponent. What’s really important is that audiences understand the character but not necessarily like everything they do.

This is another way of saying, make sure your audience empathises (but not sympathises) with your antihero.

When the audience understands a character’s reason for doing bad stuff, we’ll put up with a helluva lot.

Generate Twice As Much Empathy For An Antihero As For A Hero.

The pilot of Breaking Bad is a master class in how to generate empathy for a character who will soon turn out to be an antihero.

The pilot of The Sopranos works in a very similar fashion — both Tony and Walt have wives who are depicted as really annoying and unreasonable. In Tony’s case we see an awful mother and a criminal father — how could Tony have turned out any other way? We see his soft side (kind of) with the psychologist. We see him look after The Family.

The audience will share in their frustrations and anguish. The audience won’t share their hates.

Show the audience their hopes, dreams and fears. The audience won’t share their goals.

Since everyone feels misunderstood at times, showing other characters misunderstand them is a great way to generate empathy for unlikeable characters.

You can make them morally reprehensible but don’t make them annoying.

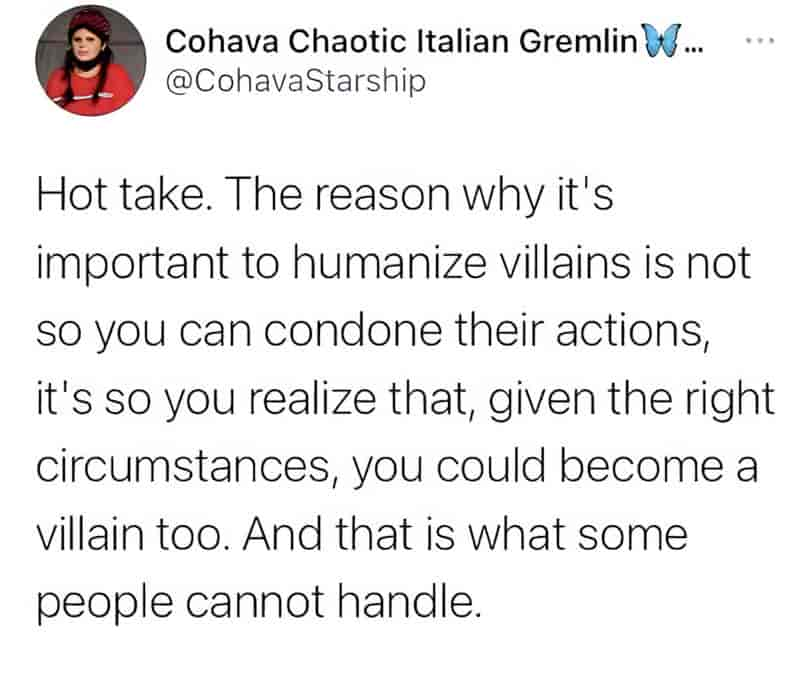

Reason being, no one wants to hang around the length of a book or a movie with an annoying character. But morally terrible people on the other hand? Well at least those people are interesting. When characters cross the line we get to see where our own lines are. That’s what these characters are for. Would we do the same in their situation? How could they have handled things differently?

USEFUL TERM

Imitative fallacy. The common trap of trying to make the narrative imitate the personality of the main character. When the novel is concerned with an unlikable or inaccessible protagonist, the narrative is also unlikable and inaccessible. Since the reader cannot figure out the main character, nor is the reader given any reason to care about the protagonist, the reader disengages. The prose must transcend the imitative fallacy. Two examples of excellence are Sinclair Lewis, Elmer Gantry (hypocritical evangelist), and Babbitt (smug placid businessman). (CSFW: David Smith)

Glossary of Terms Useful In Critiquing Science Fiction

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Watching Sympathetic Perpetrators on Italian Television: Gomorrah and Beyond

In Watching Sympathetic Perpetrators on Italian Television: Gomorrah and Beyond (Palgrave MacMillan, 2019), Dana Renga offers the first comprehensive study of recent, popular Italian television. Building on work in American television studies, audience and reception theory, and masculinity studies, her book examines how and why viewers are positioned to engage emotionally with—and root for—Italian television antiheroes. Italy’s most popular exported series feature alluring and attractive criminal antiheroes, offer fictionalized accounts of historical events or figures, and highlight the routine violence of daily life in the mafia, the police force, and the political sphere. Renga argues that Italian broadcasters have made an international name for themselves by presenting dark and violent subjects in formats that are visually pleasurable and, for many across the globe, highly addictive. Taken as a whole, this book investigates what recent Italian perpetrator television can teach us about television audiences, and our viewing habits and preferences.

New Books Network