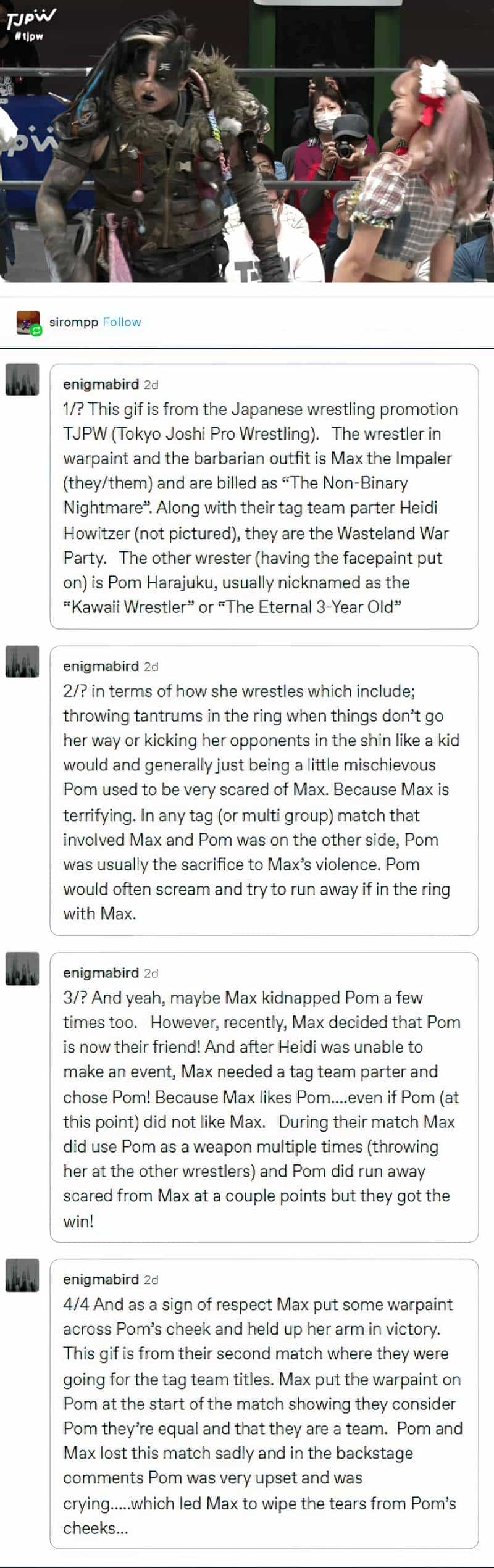

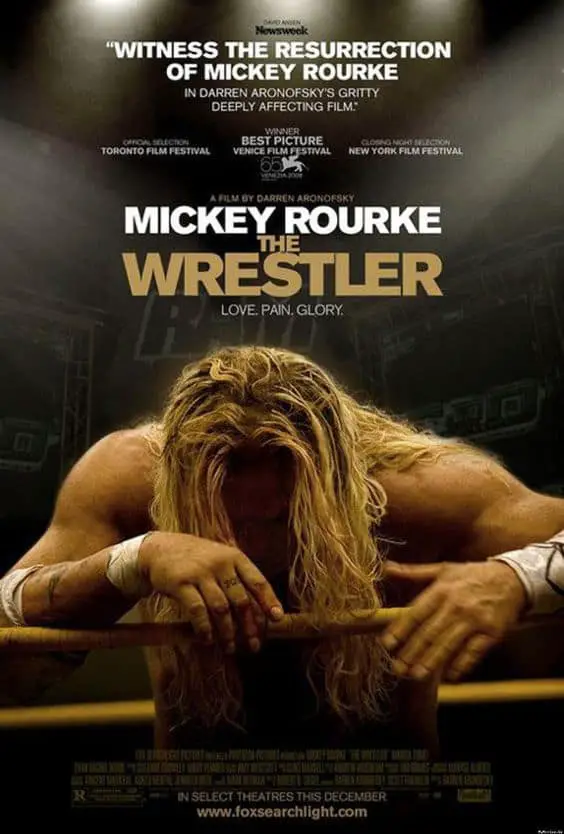

The Wrestler (2008) directed by Darren Aronofsky remains one of the best, and also one of the saddest, films I’ve seen. Australia’s Margaret and David both gave the film five out of five stars.

Logline: A faded professional wrestler must retire, but finds his quest for a new life outside the ring a dispiriting struggle.

The Wrestler is a tale of self-destruction, but self-destruction with thematic purpose. Its raison d’être is not simple masochistic pleasure — this is a critique of entertainment industries, among other things. Most of the audience is neither a wrestler nor a sex worker. This story takes the concept of masks and work life (im)balance to create a widely relatable story.

The part of Randy the Ram was written for Mickey Rourke, inspired by the emotional arc of Mickey’s life (though we almost got stuck with Nicholas Cage). Cage agreed to the role once Rourke seemed unable to play it for obscure Hollywood reasons, but soon realised he’d never get bulky enough without resorting to steroids himself. Cage didn’t want to compromise his own health in that way. So the part went back to Mickey somehow.

Mickey Rourke didn’t write the story — that was Robert Siegel — but he did rewrite his own dialogue with the director’s permission. I’ve no doubt this is part of the film’s success. Writer Robert Siegel has also written a kids’ film about a snail (Turbo) and a baseball film starring Patton Oswald (Big Fan). The Wrestler is his standout success as a writer so far.

CONTENT NOTE

I watch this film through my fingers. If you have sensory issues around cutting, blood, needles etc. you will find the wrestling sequences of this film a challenge. But if you can watch them (and not just listen, as I did), apparently the pro wrestling is real, not just realistic. The actors are real-life wrestlers, and it turns out — happily — they can also act. This should be no surprise, since pro wrestling turns out to be a form of acting in its own right.

I also find this film so affecting that it stays with me for days. If you’re not up for that, avoid avoid avoid.

The reasons for all those details, by the way, becomes clear to me after reading something about storytelling by Celeste Ng, who read a whole lot of stories in quick succession for a project she was curating. She had this to say about the forgettable ones:

Why didn’t [many stories I read] work? Partway through a story about a couple at a party, secretly struggling with infertility and on the verge of falling apart, I realized something: the characters should have been desperately sad, but no one in the story actually seemed to feel much of anything. […] enough wasn’t said. Those stories, and that shorthand, ask the reader to do all the work—of figuring out how the characters are feeling; actually, of feeling, period. They assumed you knew what it felt like to be cheated on, or to lose a loved one—and that you’d feel the same way the characters did. The authors seemed to hope you’d project your own feelings onto the character, creating instant depth, like a 3-D movie. But what does that make the characters, and the story? A blank screen. […] The best stories—the ones I still remember, months or even years after reading them, the ones that punched holes in my heart—didn’t assume anything. They didn’t use shorthand; they spelled out those feelings with painfully sharp details, so that by the end, you did almost know what it was like.

Celeste Ng

See also: Films That Centre Characters Over 40

STORY BEHIND THE STORY OF THE WRESTLER

I imagine it went something like this:

Fictionalise Mickey Rourke’s very unusual rags-to-riches-to-rags life in the entertainment industry and then hire him to basically play himself.

I imagine it also went something like this:

Tell the tale of a pro wrestler, juxtaposed against the remarkably similar female analogue of sex work, to show that even when we know what we’re enjoying as entertainment is ‘fake’, the pain of these entertainers is real. Apart from the pain on display, there’s a lot of other human suffering within these industries that we may not have considered when dismissing our entertainment as fake and therefore completely harmless.

I also like this interpretation:

Real people are phoney wrestlers (from Wrestle Zone). Or, life itself is a wrestle — power struggles with loved ones, with bosses, with our baser desires. Sometimes you’re the winner, other times the loser and sometimes life is brutal.

ESTABLISHING AUDIENCE EMPATHY FOR RANDY THE RAM

Sad stories make for good storytelling studies because they tend to be heavily character driven, and the creating team needs a good understanding of human psychology in order to affect the audience. Apart from all that, there are very clear tricks writers use when creating a story like The Wrestler. These tricks remain invisible to a general audience, but writers recognise what they are.

The more morally culpable the main character, the longer this ‘setting up empathy’ sequence needs to be. Randy is not exactly Tony Soprano. Randy the Ram is the fake, entertainment version of a Tony Soprano archetype. Both stories are set in New Jersey, but unlike Tony, the violence Randy inflicts is consensual. Still, in a story about an entertainment wrestler, who is later shown to be a deadbeat dad, a scary guy, a stroppy employee and a poor potential love interest, the writer really needs to get the audience on side before sending Randy upon his emotional journey (character arc).

CREATE SAVE THE CAT MOMENTS

Once you know what a save the cat moment is, they stand out like a sore thumb. This leads some writers to eschew them altogether. But this is a writer’s response, not a typical one.

Not one but THREE consecutive save the cat moments set Randy up as a sympathetic character:

- Randy the Ram signs for fans even though he is obviously suffering from pain after a fight.

- He is playful with local trailer park kids even though they wake him up too early the following morning.

- He brawns his favourite sex worker against some guys who are giving her grief. (Pam isn’t 100% glad to have missed out on $200, which puts some of the power back with her.)

ESTABLISH THE MAIN CHARACTER AS AN UNDERDOG

Randy is also established as an underdog character:

- He is huge in bulk, but we initially see him in a kindergarten classroom. This is never explained in the story, but I guess the wrestlers have booked a school for their event. This juxtaposition infantalises Randy and makes him appear harmless. It also makes the whole wrestling gig seem a little comical.

- While sitting on a very small chair, Randy’s manager gives him his pay, which is less than has been promised. Randy accepts it without a fight. Post-fight, he is too wasted to fight any more.

- We follow Randy home in his beat up truck and learn that his ‘home’ is a trailer park, and he sleeps in the very same truck.

- We are shown clearly how much pain he is in. We see him wince and limp and un-bandage himself. We see him mutilate himself as part of the props.

- Off stage, Randy wears glasses and a hearing aid. With these accoutrements, and the pained walk, he transforms from a formidable fighter into a vulnerable old man.

- The guy who runs the trailer park is after Randy for park fees and won’t let up even though Randy says he needs to spend his money on pain management.

- As we spend time with Randy over the following days we see why he has no money to pay his basic living costs. Regardless of how we might judge him for misusing his own pay check, he is using it to buy time with the woman he loves (Pam the sex worker). He tells her to ‘keep the change’. We have already seen he can’t afford to be so generous. He uses his pay check to buy drugs, but only drugs which will make him ‘bigger and stronger’ for his work (notably, more are offered but he reveals himself to have limits — and his own understandable logic — when he turns down cocaine and notoriously addictive painkillers). He uses his money to get foils in his hair and to rent a tanning bed. We therefore see Randy in a financial bind — the job he is employed to do requires a lot of personal outlay. There is no financial return for this weekend gig. He is addicted to the in-group prestige, and is utilised as a fighting tool by his wrestling managers, who are his pimps.

- The boss at his weekday job treats Randy like rubbish, making a snide remark about him needing more hours to buy ‘tights’. This is femme phobic of course, but mostly demonstrates how little this boss understands about the real outlays required. Tights are the least of it. Randy swallows his pride and although he has the brawn to really take this guy down, he makes an attempt to laugh at the jokey insult. Importantly, the boss is up a ladder at the time, doing some stock taking. Randy is down below. Though the viewpoint places the boss in a clearly more powerful position, it is also true that Randy could wipe out that ladder, just like that. But he doesn’t. We side with characters who have the means to wield power but keep it in check despite trying circumstances. When they finally do break out, we understand how frustrated they are.

With Randy the Ram clearly established as an underdog character who ‘saves the cat’ multiple times, the writers pull out the big gun: they give Randy a heart attack. Vince Gilligan does exactly the same thing in the pilot of Breaking Bad (but it’s lung cancer). It’s not the first heart event Randy’s had — that would be a bit too convenient and make it seem more like a contrived narrative and less like the reality show feel they’re going for. But this heart event is the worst one yet.

Now, with our sympathy firmly with Randy the Ram, the writer is free to show the audience how this character has contributed to his own situation. And we will forgive him his trespasses, as we most always do in real life when we have a fuller picture of someone.

It is definitely possible to go too far with that and turn the story into either inadvertent melodrama (specifically, a sob story) or a narrative too much to bear.

In places, it’s almost too excruciating to watch and not just for the chairs-over-the-head, staple-gun-in-the-chest horrors of the wrestling scenes; it’s the sheer, awful hopelessness of Randy’s life

The Guardian review of The Wrestler

THE CRITIQUE OF HYPER MASCULINITY AND LACK OF EMOTIONAL LABOUR

After he has a heart attack Randy makes an effort to make the personal connections he’s neglected thus far in life, while working in this hyper-masculine industry where personal connections with women come last.

So he embarks upon his plan to improve his personal relationships. First he asks his sex worker woman to go out with him, outside the club. She advises him to go to see his family. That’s what family is for.

So he goes to see his daughter. I imagine women might respond to this scene with Stephanie (Rachel Evan Wood) differently from men, in the same way middle aged women responded completely differently to Helen Garner’s novel The Room, about a woman forced to care for her friend, who is dying of cancer. I feel a lot of empathy for the daughter, who sees immediately what the situation is, and she is right, of course. Randy does need someone, a woman, to look after him. And he has very little emotional labour of his own in the bank.

When rejected so harshly by his daughter, Randy decides he will pretend his heart attack didn’t happen. He goes back to work as a wrestler. He’ll just keep fighting until he doesn’t get back up again. But watching the other old men behind the desk, the camera focuses in on their various injuries and he has his first genuine anagnorisis — he really is too old for this. The job really is going to kill him.

This is when Randy’s biggest shortcoming — his complete lack of real emotional intimacy — begins to be truly tested.

He secures a new role at the department store, but this time working with customers at the deli. Working with customers is itself taxing for someone who isn’t used to doing emotional labour. The deli is not only a customer service role but a highly symbolic job where he is serving the public by selling (actual) meat. We see him cutting meat up as we have already seen him cut his own skin with the bandaged blade.

The parallel plot line is that Randy is trying desperately to hook up with a sex worker who is not interested in him, and who is also planning to move away.

In this story, women come out better off. Randy is perfectly capable of emotional astuteness, but his lack of maturity is revealed when Pam turns him down after he asks her a second time. Because the audience has been prepped to empathise with Randy, it’s easy to forget: Randy has been told no and he’s just not taking no for an answer. This is a huge, problematic character flaw. When a younger, good looking woman turns him down, he becomes aggressive. This is left to speak to Randy’s long history with women, and explains why he has ended alone. In stories with a set up like this, it is dangerous to forget this fact.

Conditioned by society to expect care and attention from women, Randy is unable to take no for an answer. He is also a victim of this specific misogyny. He goes on a drug-fuelled bender with the first woman who shows interest in him as a wrestler (though not in him). The bleach blonde woman in the bar has fallen for Randy the Ram, not for Randy the person. He wakes the next morning to find himself in an unfamiliar bedroom plastered in posters of equally buff men. Men, as well as women, can be used sexually. On this particular night, he was little different from a sex worker. But unlike Pam, he isn’t making active choices about what he’s doing with his body.

And unlike Pam, he fails to show up for his child. This has devastating consequences.

Randy’s relationship with the two major women in his life (daughter Stephanie and sex worker Pam) are combative. The power hierarchy swings back and forth, emulating a fight in the ring, except Randy is out of control in real life. He can only cope with pro wrestling, which is staged. He can’t cope with the emotional ‘wrestling’ of real life.

Stephanie initially agrees to rekindling something with her absent ‘fuck up’ father, but when he fails to show after his drug fuelled bender all is lost for them both.

I knew Randy the Ram would botch it with his daughter. I just KNEW IT. I knew it because I know wrestlers. The business ALWAYS comes first. You can NEVER switch it off.

Wrestle Zone

The scene where Randy and Stephanie argue is highly reminiscent of mother and daughter fighting in Thirteen, and I guess that’s partly how Evan Rachel Wood was chosen for this role. (Child yells at parent, parent is culpable for leading both to this point, they both end up slumped on the floor.) But unlike the more hopeful Thirteen, this parent-child relationship has no happy ending, subverting the expectation (or the hope) that The Wrestler is going to be a redemption arc. (This counts as ‘subversion’ because the redemption story has a long, strong history in America and we’ve been primed to expect it. Even the movie poster primes us to expect it, but this is a redemption opportunity for Mickey Rourke, not for Randy the Ram.)

Randy is the loser in his real life. And when Pam comes to Randy to apologise and explain her position he takes off in his van without waiting around to hear it. Her face lets us know that she is distraught. But Randy is off to a safe, staged fight. He needs to leave this real life relationship while he has the upper hand. To him, at this moment, Pam is the loser. She does follow him to his fight, but can’t bear to watch him getting beat up.

APPEARANCE VS REALITY

Pro wrestling is a fake sport, right? Yes, but as an activity, it’s pretty real. […] It’s scripted that the villain sneaks up on the hero, who pretends not to see him, and pushes him over the ropes and out of the ring. Fake. But when the hero hits the floor, how fake is that? “Those guys learn how to fall,” people tell me. Want to sign up for the lessons?

Roger Ebert

Pretty much everything I love is all about the difference between appearance versus reality:

- Looking like an average couple in 1980s America while serving as Russian spies

- Living successfully as a guy called Don Draper, who was actually killed in the war

- Living as a high school chemistry teacher while raking in the big bucks cooking meth in Albuquerque

- Living in the snail under the leaf setting of New Jersey suburbia while working as the head of the local mafia

- Living in Utah suburbia while practising a fundamental version of accepted LDS faith which has been outlawed.

You could argue that every single narrative is about the difference between appearance vs. reality, and the very point of story itself is to let us in on another reality which is normally hidden to us — another person’s interiority — their most private of selves. But as listed above, some stories are very much about this dichotomy, and The Wrestler is another one.

DOUBLE NAMES

One significant way writers create a duality in a character is to give them another name, whether that’s a nickname, a pseudonym, a work name, or in this case, a stage name and a hooker name. (Other examples: Elizabeth and Phillip Jennings, Nadezhda and Mikhail; Don Draper, Dick Whitman; Walter White, Heisenberg; etc.)

Randy (“The Ram”) Robinson’s real name is Robin Ramzinski. The character backstory is probably that he ditched Robin because it’s a unisex name and therefore too feminine for such a hyper-masculine world. While ‘Ramzinski’ is too foreign to be memorable in an Anglo dominant culture, the Ram is perfect for its masculine aggression. Even outside his wrestling milieu, Robin hates his birth name. He has learned to feel uncomfortable with it. The industry has shaped who he really is. He has become the wrestler.

‘Pam’ is the real name of Randy’s sex worker love interest. Unlike Randy, Pam is still Pam when she’s not Cassidy at work. She feels Pam is her real name, and uses the distinction to keep her private life as a mother separate from her sex work. She will only let Randy use ‘Pam’ in certain circumstances, when he’s not with her as her client.

How these characters use their names says a lot about how they self-identify. Cassidy IS Pam, whereas Randy IS Randy. This small detail is part of the network of clues which lead us to the inevitable tragic ending; Randy can never escape because wrestling has utterly absorbed him.

DIEGETIC MUSIC

Apart from symbolic cheering and clapping at non-wrestling moments, The Wrestler makes use of a diegetic soundtrack, which gives it a documentary feel. Randy listens to 80s hair metal in his van. This music ends abruptly whenever he turns off the ignition, replaced next by silence. This abrupt switch between noisy music and silence underscores the stark distinction between two different worlds. (The 1980s soundtrack also takes us back to an earlier era, when Randy was in his prime — contrast upon contrast.)

THE PRO WRESTLING—SEX WORK ANALOGUE

Whereas one of these industries has been heavily regulated (and criminalised) throughout history, the other has not. This is part of a benevolently (and not so benevolently) sexist attitude that women (and men) need to be protected from the vice of recreational paid sex. Sex work has its very own politics.

But in many ways, pro wrestling is the perfect masculine analogue for sex work. Both industries involve penetrating the envelope of the physical body in a way no other industry requires of its workers. Both are all consuming as jobs. Both require the worker to either maintain another self or to fully incorporate their entertainment selves into their mundane-world identities. There seems to be no in between, as there is with other jobs, where we might put on a uniform (or work clothes) and change a little when entering the work arena, but not entirely. Most of us keep our names, and our inner bodies, for ourselves.

Pam is more aware of these issues than is Randy. As mentioned above, she is therefore at a huge maturity advantage, and we can see her achieving the very good life she is working towards. During the lap dance scene she asks Randy if wrestling is ‘fake’. Randy won’t admit to ‘fake’. He shows Pam his big struggle scars, sustained doing a staged but very real job.

Though we see less of Pam, Pam’s story is also a complete arc. When Randy tells his daughter Stephanie he used to pretend she didn’t exist, he is mirroring Pam, who doesn’t tell her customers she has a son (because “it’s not exactly a turn on”). Pam has her own minor story arc. At one point the camera even lets us see the world through Pam’s point of view. While this story is not The Story of a woman, the woman romantic interest is far better drawn here than in similar sports films such as Million Dollar Baby (which is deceptive, since the title suggests that film is about the female character).

THE VIDEO GAME SCENE

In one scene of The Wrestler we see Randy playing a computer game with a neighbourhood kid. The kid is unimpressed but gentle. This is an old game played on an ancient console. He is humoring Randy, who is reliving his heyday. Back in the 1980s, Randy’s avatar starred in a computer game. Now, only Randy himself remembers this retro arcade game.

Apart from highlighting the superstar backstory of this down-and-out wrestler, the computer game scene serves three main purposes:

- Randy is, in later life, keen to spend time with a child. Part of this is undoubtedly selfish — he’s reliving his heyday as a superstar. But when we see him with his daughter, we understand he is also reliving his lost fatherhood. The emotion evoked here is massive regret. Once kids are grown, there’s no second chance at parenthood. I find the song Cat’s In The Cradle excruciating in this regard, and so is this scene, in the exact same way.

- The computer game of wrestling is the ultimate fake world, existing behind a literal screen.

- Randy wants to spend more time with the neighbour kid than vice versa, emphasising Randy’s loneliness and underscoring his underdog status.

THE DOUBLE AUDIENCE

The first story reveal establishes a distinction between the film’s audience and the diegetic audience. We see the wrestlers discuss how they are going to set up the fights. In case we ever wondered, they’re staging this entirely. When they get into the ring they have to pretend they want to kill each other. Back stage, their homosocial camaraderie is apparent. They admire each other a lot. To make light of this homo-erotically charged atmosphere, Randy jokes at one point, “Now let’s all take a shower together.” (Femme phobic environs are always homophobic and vice versa, though Randy himself proves liberal and astute when it comes to his daughter’s lesbian-ness.)

THE UNMASKING SCENE

Randy becomes Robin when he grovels after more hours, any role at the department store. He wants to know why he needs ‘Robin’ written on his deli counter name tag. “They must’ve got it off your W-40 or something. Just wear the fuckin thing, all right?” With this simple name tag, the mask of the tough guy wrestler has started to peel off. He’s even wearing a shower cap looking thing which has a feminine vibe to it even though it’s worn by people of any gender working in certain industries. The camera follows Randy close behind as if he’s being filmed entering the ring. We hear the audience cheering. Then he steps into the delicatessen.

Randy starts to get into his deli job, joking with the customers, turning himself into an entertainer. But he is used to a completely different milieu and some of his customers find him over the top. He throws the product as if it’s a football. That’s not what they’ve come for.

Outside the deli Randy is really put through his paces, dealing with his own relationship messes on top of petulant customers from work. Then comes the big emotional Battle scene, which interpolates between staged Battles inside the ring.

Someone at the deli counter recognises him from his wrestling days. The mask has now come off completely. Two mutually exclusive worlds collide. Randy fails to manage his emotions and cuts his hand on the meat slicing machine. This time the blood loss isn’t planned. He quits his deli job in a rage, breaking out into full wrestler mode. This was foreshadowed by the way he came in.

THE SYMBOLISM OF THE COAT

Coats and hats are used in stories as a kind of camouflage or as a new identity. In this story there’s a symbolic coat, a recognisable part of pro wrestling world.

Hoping to make up for many missed birthdays, Randy buys Stephanie not one but two jackets. The first is the shiny one, like worn by a wrestler when entering the ring. But the second is a real coat, that will genuinely keep her warm. The two coats symbolise the ‘shiny’ surface world of wrestling; the warm coat shows that he does have some depth and is thoughtful. Significantly, the filmmakers showed us Randy buying the shiny wrestling coat, but kept the second coat as a reveal. This is how they make this scene so affecting. It is so heartwarming and such a relief to see that Randy was able to understand, off-stage, that Stephanie would not like a wrestling jacket. She hates the wrestling-world side of her father. Wrestling stole her father from her.

HIGHLY SYMBOLIC PLACES

Randy takes Stephanie to a highly symbolic place — an abandoned theme park — a place he remembers but she doesn’t remember much. Abandoned places make such great shooting locations because they mirror the emotional wrecks of main characters.

This film has highly symbolic shooting locations in general: I’ve already mentioned the kindergarten. Below I mention the womb symbolism of the ‘ring’.

The weather is also symbolic, with much of it taking place in winter. Yet there’s a lot of upper-body nudity, more suited to warmer climes. It’s significant that where Randy and Pam are naked they are most like their fake selves. Unlike the usual symbolic meaning of ‘naked’, these two are more authentic when wrapped in multiple layers.

THE TRAGEDY OF A FAKE ANAGNORISIS

When a character does not get what they want, we call it a tragedy. What does Randy want? Real, human connection. Too late in life, and only after a health scare, he has jumped in head first. He’s opened up to Pam and apologised to his estranged daughter. He really has tried to be his real self.

And he does earn a genuine Anagnorisis. We are shown evidence of this anagnorisis back stage with Pam, who has chased him down, hoping to start something. He rejects Pam and includes her in ‘the outside world’ when he says, “no one out there gives a shit about me”.

But then Randy gets into the ring. There he makes a mock-heartfelt comeback speech.

American filmmakers love big speeches with big audiences. Normally this big speech is used to show the (real) audience (as well as the diegetic audience) that the character has had a anagnorisis, but Randy tells his setting audience that they are ‘all his family’, contradicting the self-awareness he displayed with Pam. This ‘big speech’ scene therefore subverts the storyteller’s trope of teaching the audience a thematic lesson via a self-revelatory speech.

In other words, Randy has had a anagnorisis but he replaces it immediately with a false one, and suppression of his real human needs will lead to his downfall. Continuing like this, he will remain unable to lead a fulfilling life. Then he will die.

DOES THE ENDING WORK FOR YOU?

The Wrestler has one of those endings that divides viewers. This is always the case when the storyteller leaves the audience to extrapolate the new situation part of the story for ourselves. Some viewers just don’t seem to be be able to do that, even after being given all necessary information. Others absolutely love it when we are given enough information to extrapolate.

We don’t see what happens to Randy when he returns to real life, because for Randy there is no ‘real life’. Any number of filmmakers would have chosen to leave us with a scene showing Randy back in his van, pumping himself with more drugs, or similar variations on that. But it’s hugely fitting that Randy ends with a wrestling scene. That’s his home (and cage) forever.

THE SLAVERY-FREEDOM ARC

In the vast majority of stories, characters begin in a state of entrapment then find their own version of freedom. (Note that main characters are ‘trapped’ by their own shortcomings rather than literally, and that is definitely the case for Randy. No one’s put handcuffs on the guy.)

The Wrestler fits in the type of story that moves from entrapment to temporary freedom to greater entrapment to death. If you want to write ‘heartbreaking’, use this arc. I find this arc even more tragic than the arc of a tragedy like Hamlet, because we had a glimpse of how Randy’s life might have looked had he made different choices. He was so close to achieving a lasting relationship with Stephanie and with Pam. If only he hadn’t blown it. If only. This arc invokes the strong emotion of regret.

The last we see in The Wrestler, Pam turns to leave, clearly disappointed. We know from her face that their budding relationship is over; we have already been shown that she has plans to move away. We know that’s what she’ll do. We have also been shown that, in many ways, these two are ‘soul mates’ — they might really understand each other if only they both opened up.

Next we see a low-angle shot of Randy as he climbs the ropes of the ring then throws himself belly first onto the platform.

The film fades to black. One interpretation is that the fall kills Randy on the spot, but that would be too tidy for a film so cinéma vérité.

I extrapolate that this is how Randy does exit life, but on another day. With a heart weakened from drug use and fighting, he will go out with a bang. This ending is his spiritual death. His literal death will probably be another iteration of this exact scenario, with Randy safely ensconced (enslaved) inside the ring as he once was in the womb, the circle (‘ring’) of life complete, surrounded by his fake ‘family’.

FURTHER RESOURCES

I really liked the discussion of “The Wrestler” at the “You Are Good” movie discussion podcast. The following observation is an insightful thing for all writers of fiction to consider. This refers to Mickey Rourke’s character walking around a dollar store hunting for cheap wrestling props:

Just like spending time watching someone live their life is, to me, something I wish we saw more of. Cos I feel like there’s such pressure to get people In A Story! immediately. I mean, I like stories. But I also just like watching some guy named Randy doing his thing.

And I also think that makes you, potentially, feel very bonded with the character over time. Like, you’re just quietly with them. It does something to your feeling of presence in their life, I think. It made me feel a lot of intimacy with this character. And I wanted things to work out differently.

“The Wrestler w. Gaby Dunn”

Also interesting in the podcast: How Randy the Ram represents America, which as a non-American went over my head a bit. They recommended a documentary called Resurrection of Jake the Snake, which is a documentary with pretty much the same storyline as this fictional one of Randy.

Resurrection of Jake the Snake Trailer from Comeback Studios on Vimeo.

They also recommend two other documentaries set within the same social milieu and American economic class:

- Heavy Metal Parking Lot — a short film shot in 1986, interviewing a variety of interesting characters who had lined up to get into a heavy metal concert. Currently available on Vimeo.

- A similar thing called American Juggalo, which you can also currently find on Vimeo: “American Juggalo is a look at the often mocked and misunderstood subculture of Juggalos, hardcore Insane Clown Posse fans who meet once a year for four days at The Gathering of the Juggalos.”