For some characters, self-reliance and a refusal to silence their inner voices strengthen their public voices. For others, art provides a metaphorical expression of voice. Often characters recognise the dialogic nature of voice: their voices exist only in dialogues with other people. … They recover their voices because they recognise the power of language. … Regarding voice and silencing, Barbara Johnson writes…that “aphasia, silence, at the loss of the ability to speak” results when the woman is reduced to playing only one role. Johnson makes much of the “distinction between speech and aphasia, between silence and the capacity to articulate one’s own voice.”

Waking Sleeping Beauty, Roberta Seelinger Trites

It’s easy to forget that women have had few opportunities to speak throughout history. This isn’t often reflected in period dramas:

For much of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, women’s parts in plays were taken by boys. Speaking on the stage was considered to be very unladylike in the early seventeenth century. Although royal and aristocratic women appeared in court masques in the early seventeenth century, there was no question of them uttering, however magnificently they might be dressed.

The Restoration saw the first possibility of a successful career on the stage for women. … Though the ratio of men’s parts to women’s was about 2:1, some companies had nearly as many actresses as actors.

Women in England 1500-1760: A social history by Anne Laurence

Popular wisdom holds that women talk incessantly; research shows that in mixed-sex discussions it’s men who do most of the talking. The pattern is consistent, and statistically robust. The settings where it has been documented include not only laboratories, but also school and university classrooms, academic conferences, committee meetings, town meetings, Parliamentary debates and the comments sections of news websites.

Language: a feminist guide

Below is a transcription of a scanned article published in an 1899 edition of The World Wide Magazine. You’ll find it over at Internet Archives. Content note: Internalised misogyny (of course).

I feel keenly after reading this that the women who ended up at that 19th century silent convent were there to escape trauma. The routines of the convent may have provided some initial relief, though as becomes apparent, the silent nunnery itself inflicted its own trauma.

If you’ve ever read The World According To Garp (1978), or seen the film adaptation (1982), you may remember the resonant detail of the Ellen Jamesians, a group of (fictional) women named after an eleven-year-old girl whose tongue was cut off by her rapists to silence her. When creating this plot, John Irving was surely cognizant of historical cults such as the Buried Alive nuns of the 1800s, in which the highest virtue a Victorian-era woman can attain is to keep quiet forever, nun or not. The novel was written during second wave feminism.

Unfortunately, this feels to me like commentary on what many conservatives considered ridiculous and self-flagellating feminist activism of the time.

As I read about the silent nuns of the Pyrenees I also thought of the sensibility of Hans Christian Andersen, especially as expressed via his story “The Little Mermaid” (1837). I have no idea if Andersen knew about this particular silent nunnery, or of any of silent commune, but that doesn’t matter. The silent nunnery aspires to one outworking of ‘perfect femininity’. (The other is ‘mother’.) This ideal was widely valorised. It affected how women were expected to behave, and it affected fiction.

The silent nuns of the article below are described as plucky, hard-working, courageous and most of all virtuous because of their silence.

There are some striking resemblances between The Silent Nuns and Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid”:

The Little Mermaid says she would trade three hundred years of life as a mermaid for one day as a human, if she can trade up for a soul and immortality. She is more interested in the life beyond death than her life on Earth. Likewise, the nuns wish for death. They embrace it when it beckons.

The silent nuns don’t have many possessions but there are two things that seem really, really important to them: A statue (not of a boy, but of Our Lady of Sorrows). The other is the natural world, which surrounds them. Remember how the Little Mermaid is into flowers?

The Little Mermaid drinks a potion which takes her away from her natal environment (the sea) to a completely different one (the land of humans). Once she grows legs, she can never return to her natal home. Likewise, entry into a nunnery means you can never go back to your original life. And even if you can technically leave the premises of your own free will, you are very quickly institutionalised under such a strict (and I’d say abusive) regime.

But what made me think of “The Little Mermaid” was — of course! — that Andersen’s heroine loses her voice. She must give her voice to the Sea Witch as payment for becoming a woman. She will be a woman, all right, but a mute one.

Although she can’t speak or sing (or perhaps because of it), the former mermaid’s beauty is remarkable. This is from the article below, but might also be straight out of “The Little Mermaid”:

The nun turned at once towards them and threw back her hood, showing the most exquisite face of a girl of eighteen. A murmur of admiration and pity escaped from everyone.

A silent woman is a beautiful woman. When Sally Rooney’s Normal People was adapted for TV, a number of readers complained that the actress cast to play Marianne wasn’t ugly, whereas in the book she is described as ‘the ugliest girl in school’. What does ugly mean to the boys at Marianne and Connell’s school? Marianne speaks too much. She was in fact cast accurately.

Back to “The Little Mermaid”. Andersen’s Little Mermaid never finds her voice and endures a tragic ending. Her beloved husband has fallen for someone else, who is perversely and tragically the Little Mermaid herself. (He sounds like a dick. Love the one you’re with, dude.)

Disney knew their main audience was kids, so they changed the ending when they adapted it for film in 1989. Stories like this now felt maudlin. Andersen never meant his stories to be maudlin. To him, a story ending in death was happy. It meant you were now reunited with your dead loved ones and could live happily for eternity. He did the same thing in “The Little Match Girl.” Dead and in Heaven? With Grandma? Yasss!

1980s audiences no longer believed that death is a, ah, happy ending. In the Disney adaptation a helpful seagull intervenes near the end. Ariel gets her voice back. Ariel lives with her prince happily ever after right here on Earth.

The Silent Nuns of the Pyrenees never got their voices back. They never spoke to anyone, except to pray. They never looked up from the ground. Then they died in middle age, their own deaths welcomed, Hans Christian Andersen style, ill-health hastened by malnutrition. The lack of social interaction couldn’t have helped their will to live.

The silent nuns of the Pyrenees were the real life Little Mermaids.

“Where Women Never Speak” by Mrs. Herbert Vivian

Being a description of a remarkable community — a nunnery whose members are under a vow never to speak. Small wonder that they die young after so unnatural a life. In Italy they are known as “Sepolte Vive” (the Buried Alive)

WHERE ARE THE ‘BURIED ALIVE’?

Far down in the south-western corner of France, on the borders of Spain and under the shadow of the Pyrenees, there dwells the strangest and most austere order of nuns in the world.

THE RULES

These are the Bernadines of Anglet, sisters of Saint Bernard, the almost incredible severity of whose rule most resembles that of the famous Trappist monks. Indeed, they appear even more meritorious when one remembers that weak women cannot bear the same hardships or sufferings that men can.

These devoted nuns abandon themselves to a life of solitude and take a vow of perpetual silence, which everyone must allow is far more praiseworthy in a woman than in one of the sterner sex. When I was staying at Biarritz recently I heard so much about these nuns, and such interesting tales about their lives, that I determined to go over to the nunnery of Anglet, and visit them in their hermitage among the beautiful pine forests.

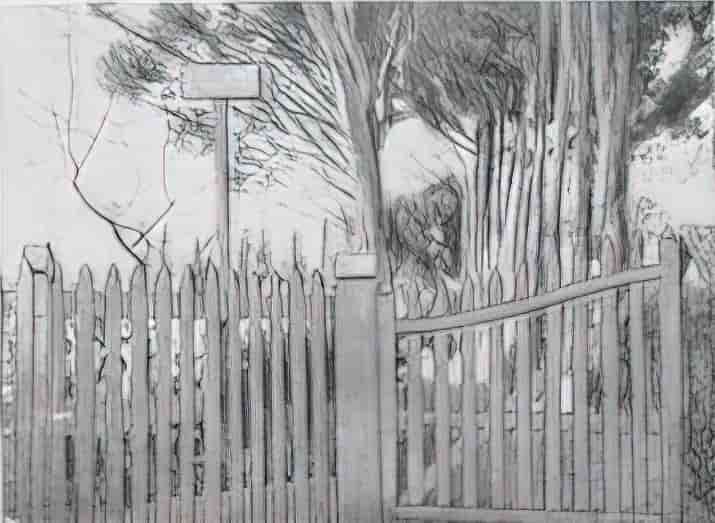

I drove through sandy dunes and pine woods, and at last found myself before a wicket-gate, opening upon a long avenue of pine and poplar trees.

Here the sense of monastic seclusion came over me at once, for on a sign-board near the gate I read the words, “Prière de parler à voix basse.”

As the Bernadines themselves may never speak or even look at anyone, it was no use addressing myself to them, but I soon espied a kind, cheerful-looking Sœur de Marie [Sister of Mary], belonging to an adjoining convent, reading some holy book beside a little shrine. She put the work aside at once, and volunteered in a whisper to take me over the Bernadine quarter. She led me through a high wooden gateway, and then I found myself in a garden shut in on every side by low white buildings.

WHAT THE SILENT NUNS LOOK LIKE

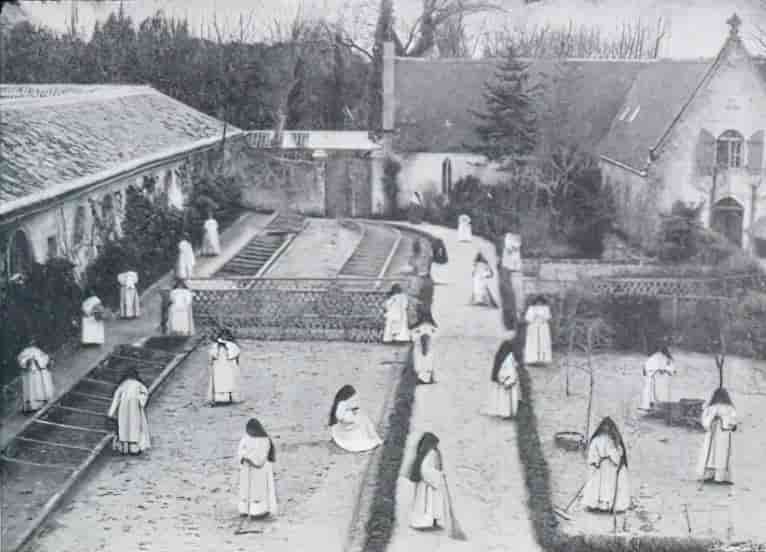

Here were a number of white figures not unlike bales of coarse flannel. Over their heads, and arranged so as almost to conceal their faces, were long black woollen hoods, which were rendered the more striking by the great white crosses that were affixed to the backs. Each nun wore rough wooden sabots [peasant shoes, hollowed out wooden shapes shaped like clogs], and round her neck a chain, to which was attached a large cross. There was little of the appearance of the ordinary nun about their attire, which contrasted strikingly with the flowing dark blue robes and snow-white coifs [a woman’s close-fitting cap worn under a veil by nuns] of the The Sœurs de Marie.

WHAT THE SILENT NUNS DO WITH THEIR DAYS

All the silent Bernadines seemed very busy — raking, hoeing and weeding; and I noticed that none of them lifted their eyes from the ground, or seemed aware of our presence. My companion told me that, according to the rules, all curiosity of the eyes must be mortified.

A VISIT FROM THE FRENCH EMPEROR

When the Emperor of the French visited the convent in 1854, he asked to be allowed to see the interior of a cell. The Abbé Cestae, founder of the monastery, threw open the door of one, disclosing a nun seated on a wooden stool at needle-work, her back turned to the door. She did not move, but went on working quietly.

“May we not see her face?” asked the Emperor.

“My child,” said the Abbé, “the Emperor and Empress are at the door of your cell and wish to see you.”

The nun turned at once towards them and threw back her hood, showing the most exquisite face of a girl of eighteen. A murmur of admiration and pity escaped from everyone. The Bernadine, however, remained absolutely unconcerned, with her hands crossed on her breast and her eyes cast on the ground. She did not seem to be aware of their presence.

“Your Majesty sees,” said the courtly Abbé, “how implicitly the Bernadines obey their rules. Not even for the privilege of beholding an Emperor will they raise their eyes from the ground.”

THE GROUNDS

Scattered about in the garden are various shrines, containing images of the Virgin and the Saints, and on summer days the Sisters come and sit near these with their needle-work. The Bernadines, by the way, are famous for their exquisite sewing. They make a great many trousseaux, and I was shown a large stock of fairy-like embroideries for church linen, and handkerchiefs which must have taken many weeks or months to make.

Under a thatched shelter stands a beautiful group of Notre Dame de Pitié [Our Lady of Sorrows], which was presented by a lady who had lost everyone she loved.

Here the Bernadines often come to pray for the souls of the departed, while others saunter along the neighbouring footpaths wrapped in pious meditations, utterly oblivious of the great world outside.

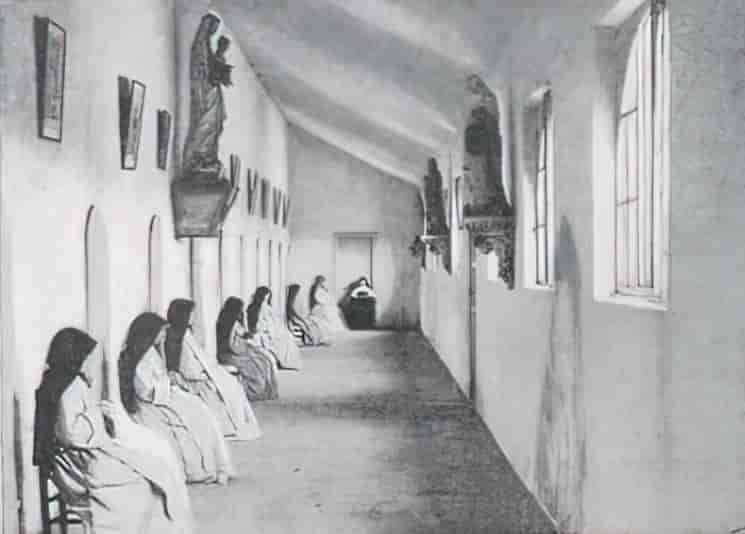

THE CHAPEL

My blue-robed guide next took me into the chapel, which serves as a place of worship for the Sœurs de Marie as well as for Bernadines themselves, who, faithful to their vow of solitude, have their portion divided off by a curtain, behind which they listen to the Mass. The only occasion on which the nuns open their lips to speak is when they join in the prayers. If it were not for this they would probably almost forget how to talk!

OUR BLESSED LADY OF SORROWS: THE STATUE

On the altar of the chapel stands an image of Our Lady of Sorrows, draped in crape, and wearing an expression of infinite sadness. In her hand she holds a crown of thorns, and on her breast is a heart pierced by seven swords. There is a strange story as to how the image came to Anglet. Many years ago, during the first Carlist war, a number of Spanish refugees took up their abode near Bayonne, and the Convent of the Bernadines was one of their favourite places of pilgrimage.

Amongst them was a lady of most distinguished appearance, who was remarked for her piety. One day, after she had been praying for many hours in the chapel, she came to the Abbé and said to him: “Father, I will send you a statue worthy of the Solitude.” Some months afterwards the image arrived, but no one knew whence it came or who was the donor.

Long afterwards, when the Abbé was in Madrid, being overtaken by a storm one day, he sought refuge in a convent. On being asked his name, he replied that he was the Abbé Cestae of Anglet. The Prioress suddenly became very much interested and welcomed him warmly, saying, “Ah, it is you then who have Our Blessed Lady of Sorrows. Shall I tell why we sent her to you?

At that time our abbess, the Royal head of the convent, was for a long while exiled in France. Suddenly she came back to us one day, but although we were in transports of joy at the sight of her, she seemed strangely sad and preoccupied. At last she said, ‘Daughters, it is true that I have been restored to you again, but alas! we have a heavy price to pay for my return. During my stay in France I made many a pilgrimage to the convent near Bayonne. One day, as I was praying, a Divine voice whispered to me, “You shall no longer be persecuted — you shall return again to your own land, but in return for this you too must make a sacrifice. You must offer up the beloved statue of Our Lady of Sorrows.”‘ The sisters were over-whelmed with grief, for our Abbess could not have demanded a greater sacrifice. However, for her sake we yielded, and you, my father, now possess our most sacred treasure.”

THE FOUNDING OF THE CONVENT AT ANGLET

It was the Abbé Cestae, a saintly priest of Bayonne, who founded the convent at Anglet in 1839. […] At first, owing to lack of funds, the nuns went through every sort of suffering, often having absolutely nothing to eat and no prospect of obtaining anything. However, by sheer pluck and hard work these courageous women overcame every difficulty, and now, although they are not rich, they can at least provide themselves with the necessaries of life. Their needs, after all, are very small.

FOOD

They fast constantly, and when they do eat, their food consists of vegetables, dry bread, and, three times a week, a little — a very little — meat.

THE REFECTORY

The refectory is a long, narrow, whitewashed room with a thatched roof and no artificial flooring, merely the deep sand of the dunes, which, however, provides the most comfortable of carpets. Each nun has her earthenware pitcher of water and a little drawer in the rough deal table where she keeps her wooden spoon, fork, and platter. On Fridays the Bernadines take their meals kneeling on the sand. At the appointed hour they make their way in single file to the refectory.

THE PRAYER SCHEDULE

Every hour of the day is carefully mapped out, for the rules of the Order insist that not a moment shall be wasted. There are constant prayers on every occasion. Each time the big clock of the monastery chimes the hour, every nun falls on her knees and spends a few moments in prayer. Out in the fields it is marvellous to see how well the oxen know those chimes. Directly they hear them they stop instinctively, starting on their way again the instant the Sisters rise from their knees.

NUN BUILDERS

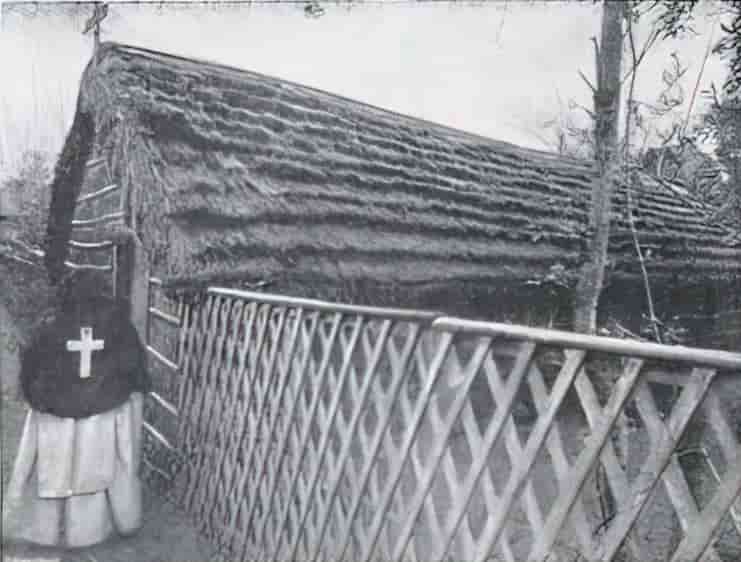

These wonderful women have actually built their own houses, workmen being only called in to put on the roof! At first these were most curious little huts, made (walls and all) entirely of thatch. They were but 7ft high by 7ft broad, and had no window. Underfoot was sand, and the furniture consisted merely of a wooden chair and a bed made of branches, on which was piled a layer of straw or dry leaves. A rough woollen coverlet and a little hard pillow completed the bedclothes.

LIFE EXPECTANCY OF SILENT NUNS

These huts were used for many years, but at last they were obliged to be discarded, as the number of deaths caused by the cold and wet was appalling. My cicerone [a guide who conducts visitors and sightseers to museums, galleries, etc.], the courteous Sœur de Marie, took me to see one of these little huts, which is still kept as a relic of the past. She told me that even now the Bernadines are but short-lived. Hardly one of them reaches middle age, and even in the prime of life they look like aged women.

THE BEDS

However, though the original plan may have been modified, the result is just the same, and the Sister impressed upon me that the beds were not a whit less hardened and uncomfortable than they used to be. […]

SEWING OBLIGATIONS

Even during recreation [the Bernadines] are not allowed to rest, but are always busy with their needles. […] there are no fires whatsoever at Anglet.

WRITING ON THE WALLS

Round the walls are a few pictures and sacred images, and everywhere one reads admonitory texts and verses, such as: “If you remember your sins, God will forget them; if you forget them, He will remember them.”

THE THATCHED CHAPEL

The thatched chapel is a very quaint little structure. The floor is, as usual, of sand, and tiny windows, set in the thatch walls, give a very dim, religious light. On the altar is a statue of the Virgin, and below it another of Our Lord, stretched on a couch.

VISITS FROM ROYALTY

An inscription at the door relates how Queen Victoria visited the chapel and prayed there, when she was staying at Biarritz in 1889. Prayers have been granted in the most miraculous way, said the Sister. The Empress Eugenie came here to beg for a son, and remained a long time, praying with much fervour. As she was leaving, the Abbé Cestae said to her, “Madam, the most Holy Virgin has vouchsafed to me the knowledge that your request will be granted. Do not fear, for assuredly your prayer has been heard.”

And, strange to say, some months later a little Prince Imperial came into the world.

THE CEMETERY

The cemetery is as austere-looking as the rest of the nunnery. The graves are the simplest little sandy mounds huddled close together in the most pathetic way, with a rude cross traced in cockle-shells upon them.

At the head of each is a little bush, while firs and gloomy cypress tress are dotted around. Here the nuns spend much of their time, praying for the souls of the dead, sometimes at the grove of the Abbé Cestac’s father, a holy man who is buried here; and sometimes in the tiny thatched chapel which they have erected. […]

THE BERNADINES AS O.G. GOTHS

The Bernadines have no fear of death. Indeed, on the contrary, they long for it. When the first Superior of their Order lay a-dying she had an interview with one of the nuns, who implored her to intercede on her behalf in Heaven that she too might die soon.

The Superior smiled, and in an inspired voice said that in a month her request should be granted. On the day of burial, just as the coffin was to be closed, the nun drew near to the body, whispered in its ear, and slipped a note into the dead hand, imploring the Superior not to forget her promise. Just a month from that date the nun, too, passed away, and so the promise was fulfilled.

SILENT NUNS THROW A PARTY

Although it seems hard to believe it, the Bernadines do sometimes have their feast days. […] All Saints Day […] in the Pyrenean provinces is counted as one of the greatest of religious festivals. An altar is erected and beautifully decorated at the end of the long avenue of poplar trees, and here the nuns assemble with banners and crosses. Even then, however, everything is so subdued and noiseless that it seems hard to believe that they can be rejoicing.

THE TRAGIC TALE OF TWO SILENT BEST FRIENDS

Perhaps the following story will illustrate better than any mere description how minutely the penitential rules of this extraordinary Order are obeyed. Two Bernadines lived side by side for five years in two adjoining cells, and so thin a partition divided them that they could even hear the sound of each other’s breathing. All this time they ate at the same table and prayed in the same chapel. At last one of them died, and, according to the rule of the Order, the dead nun was laid in the chapel, her face uncovered, and the Bernadines filed past, throwing holy water upon the remains as they went. When it came to the turn of the next-door neighbour, no sooner did she catch sight of the dead nun’s face than she gave a piercing shriek and fell back in a swoon. She had just recognised her dearest friend in the world, from whom she had parted with the deepest pain many years before to enter the convent. For five years the two friends had lived side by side without ever having seen each other’s face or heard the sound of one another’s voice.

SEE ALSO

In Female Monasticism in Medieval Ireland: An Archaeology (Cork UP, 2021), Dr. Tracy Collins writes the first archaeological investigation into female monasticism in medieval Ireland, primarily from the twelfth to sixteenth centuries. Weaving in early medieval evidence, textual sources, and examples from Britain and the continent, new considerations are given to the archaeology, architecture, and landscape through the lens of gender. Introducing her results from her recent surveys and excavation, she reveals the fluidity and diversity of female religious communities in Ireland. Debunking stereotypes such as strict enclosure and uniformity, Collins provides a glimpse into the lives of medieval female religious and their connections locally as well as within Ireland and Europe. Dr. Tracy Collins was a co-founder of Aegis Archaeology Limited and currently work as a state archaeologist with the National Monuments Service in Ireland. She is also co-editor of the upcoming Brides of Christ: Women and monasticism in medieval and early modern Ireland (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2022).

New Books Network

Listen to a podcast interview here.

The traditional view in the songbird research world is that male birds sing elaborate songs to attract a mate, while females stay silent. Now Southern Hemisphere songbird researchers, such as those in Massey University, Auckland, are challenging this.