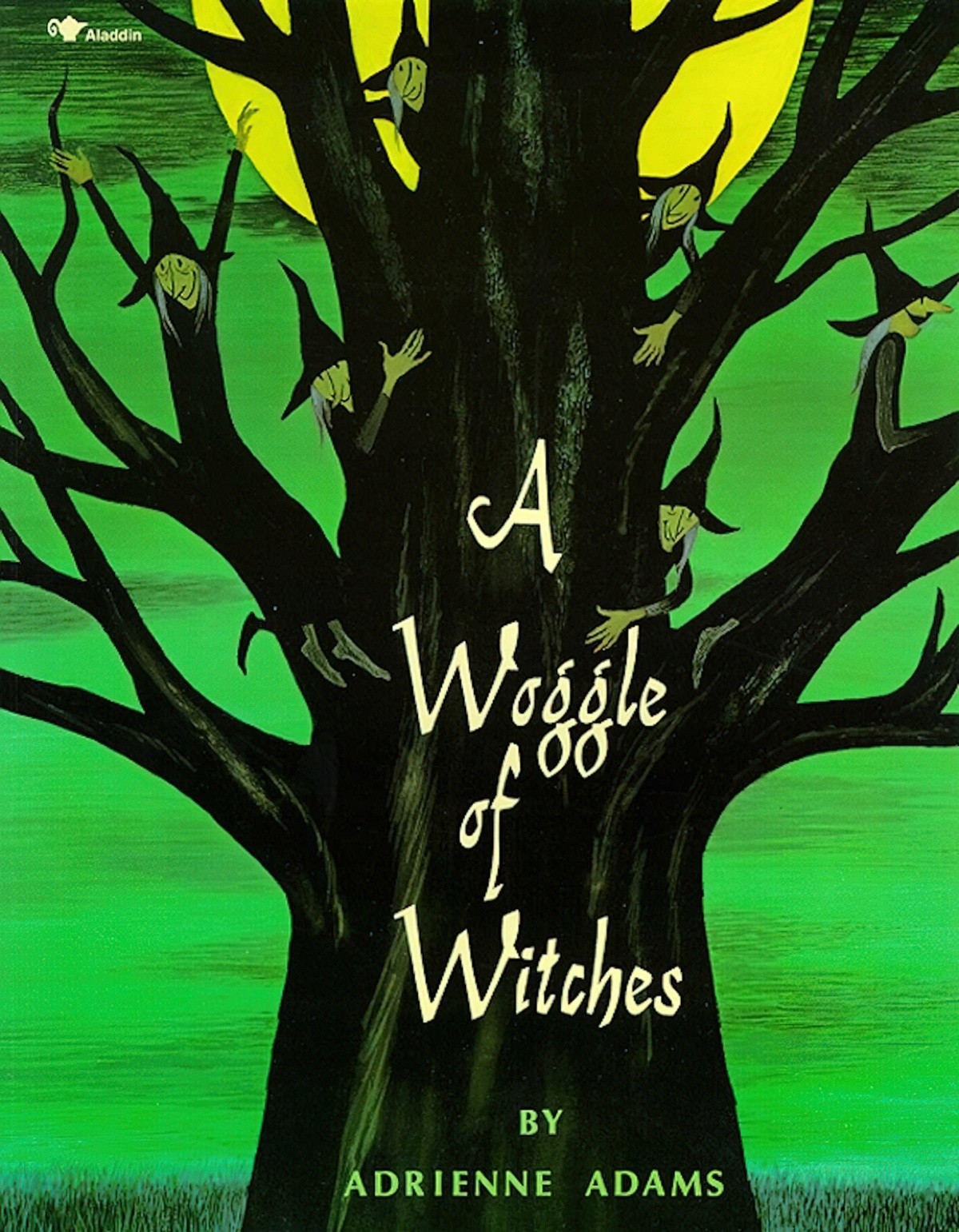

A Woggle of Witches is a picture book written and illustrated by American storyteller Adrienne (“Dean”) Adams in 1971. In total, Adams wrote six of her own books; mostly they illustrated for other writers.

Adrienne Adams was a prolific illustrator through the 1960s and beyond, and a two-time winner of a Caldecott Medal (1960 and 1962). Adams was born in Arkansas in 1906 and grew up in Oklahoma. They studied in Missouri.

Everyone called Adrienne ′′ Dean “, which makes me wonder what Adams’ gender identity would have been if they were born ~70 years later and had more options.

For a couple of years they worked as a teacher and started illustrating while teaching. They would wake before dawn, then draw until it was time to go to work. Adams moved to New York, where they enrolled in the American School of Design. They got their start illustrating all kinds of things from fabrics to greeting cards.

In 1935 Adams married John Lonzo Anderson. He was a Harvard graduate who wrote children’s books. Adams illustrated them. Adams dedicated books to him, and he dedicated books back to Adams.

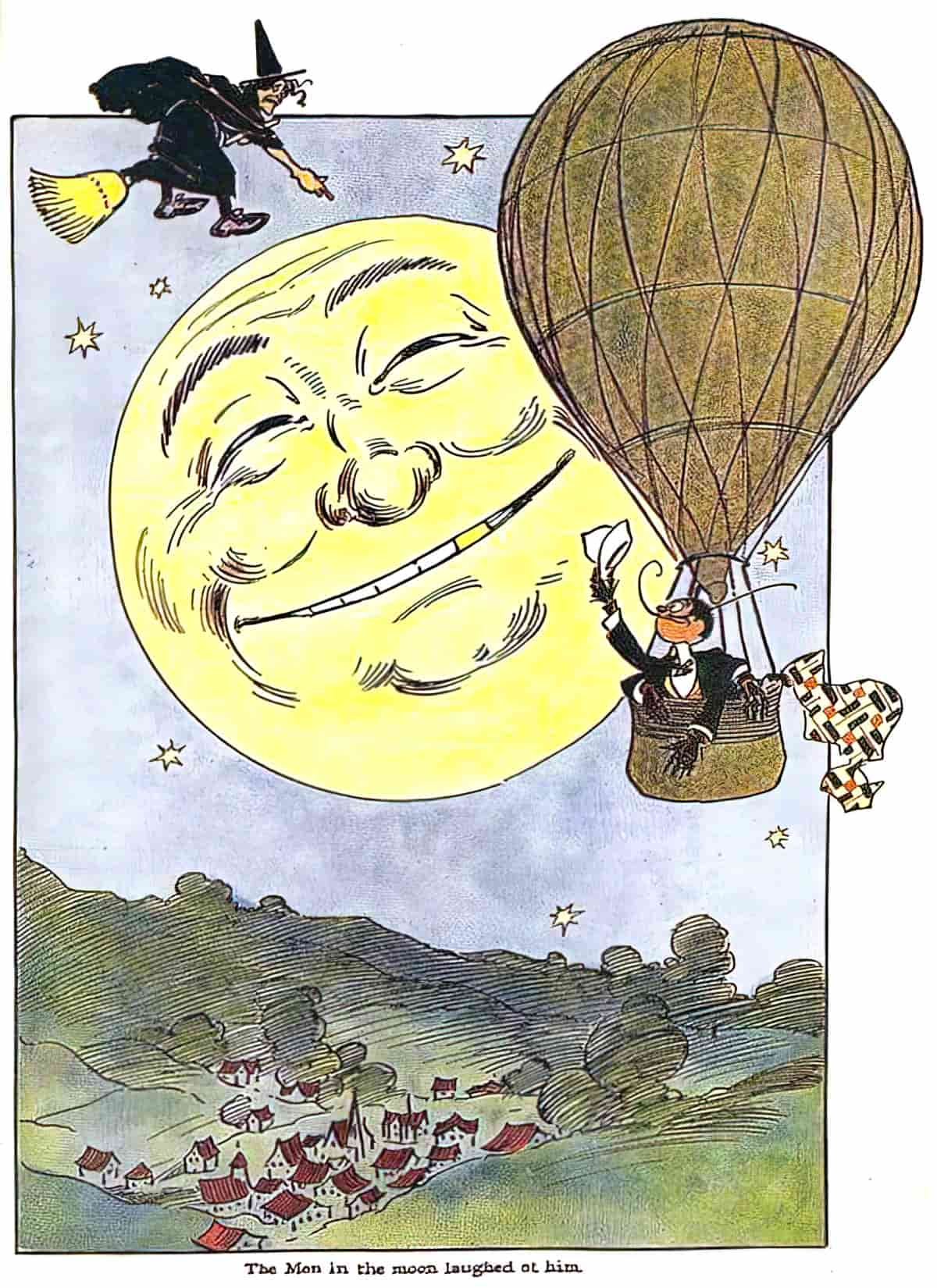

Their first collaboration was Bag of Smoke (1942), the story of the French Montgolfier brothers, who invented the first practical hot air balloon.

Anderson and Adams were a couple who collaborated on all things: Adams would make the bread, he would grind the flour. In an era where the husband normally did all the driving, they shared the driving of their Volkswagen RV.

Witches were a favourite theme for Adams. Aside from A Woggle of Witches:

- A Halloween Happening (1981) — pair with this book

- The Littlest Witch (1959) written by Jeanne Massey

- Painting the Moon (1970) written by Carl Withers

Anderson died in 1993, and Dean in 2002. They share a headstone.

SETTING OF A WOGGLE OF WITCHES

The cover of A Woggle of Witches depicts a fetching green sky. Green skies are associated with the approach of hurricane.

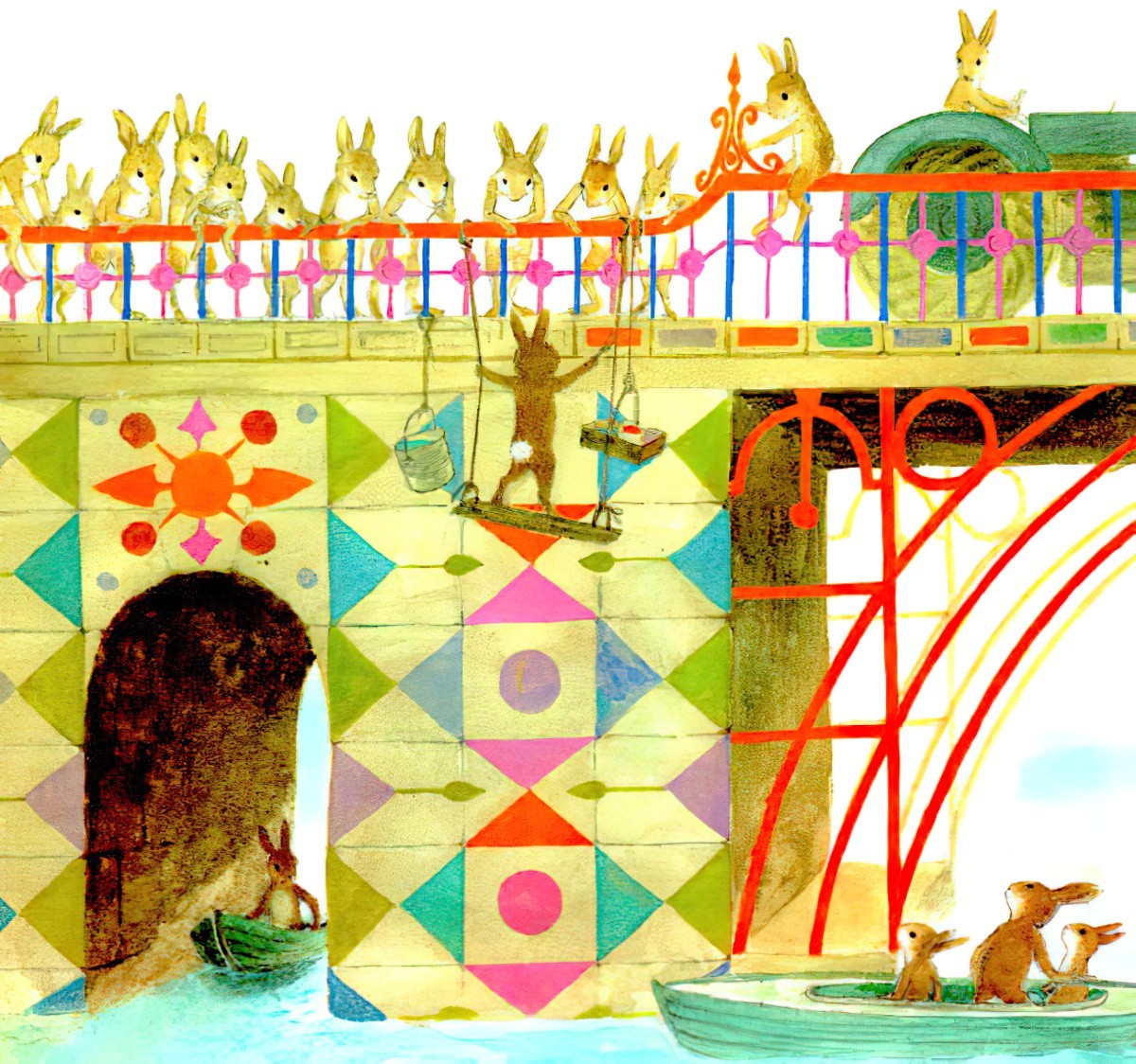

Otherwise, this is basically a cosy fairytale world, but with the addition of contemporary children entering the story near the end.

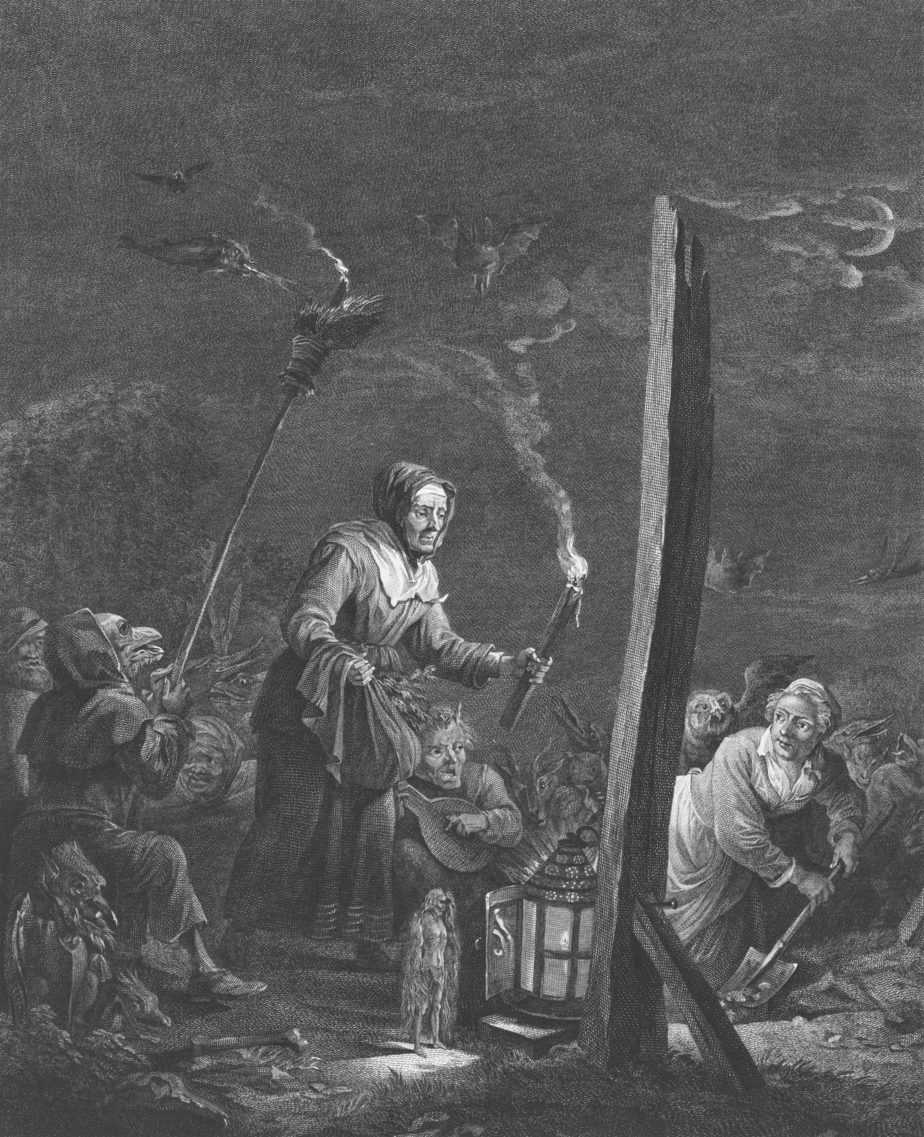

Witch stories for children have at their base a terrifying story of persecution. Below is a drawing of another witch on a broom. Here’s the harrowing difference: This one was drawn during the witch craze, and women who really looked like this (ie. older women, women with breasts which have fed and nurtured) were oftentimes suspected of witchcraft in a social climate where people really truly believed witches lived among them.

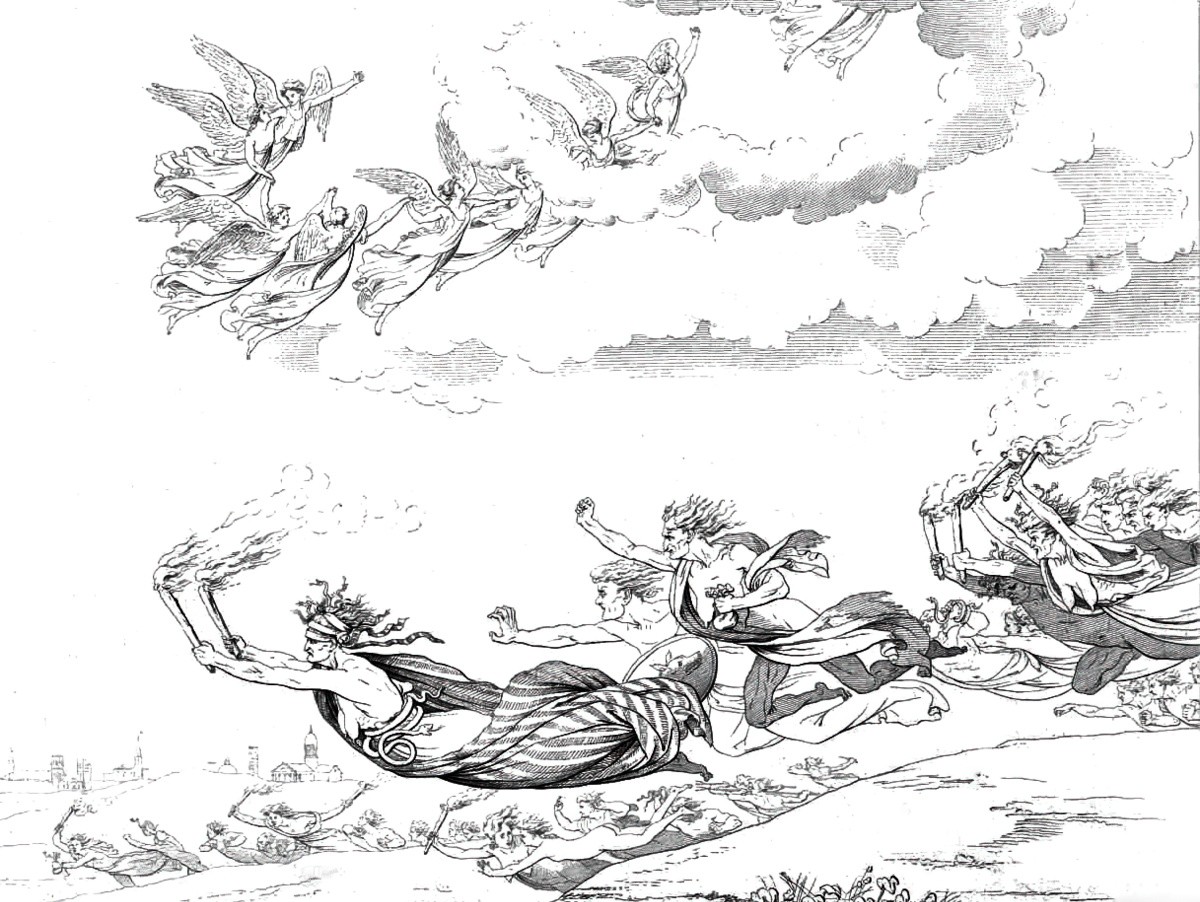

Belief in witches lasted for centuries. The example below is from 1808. Many still believed in witches at this point.

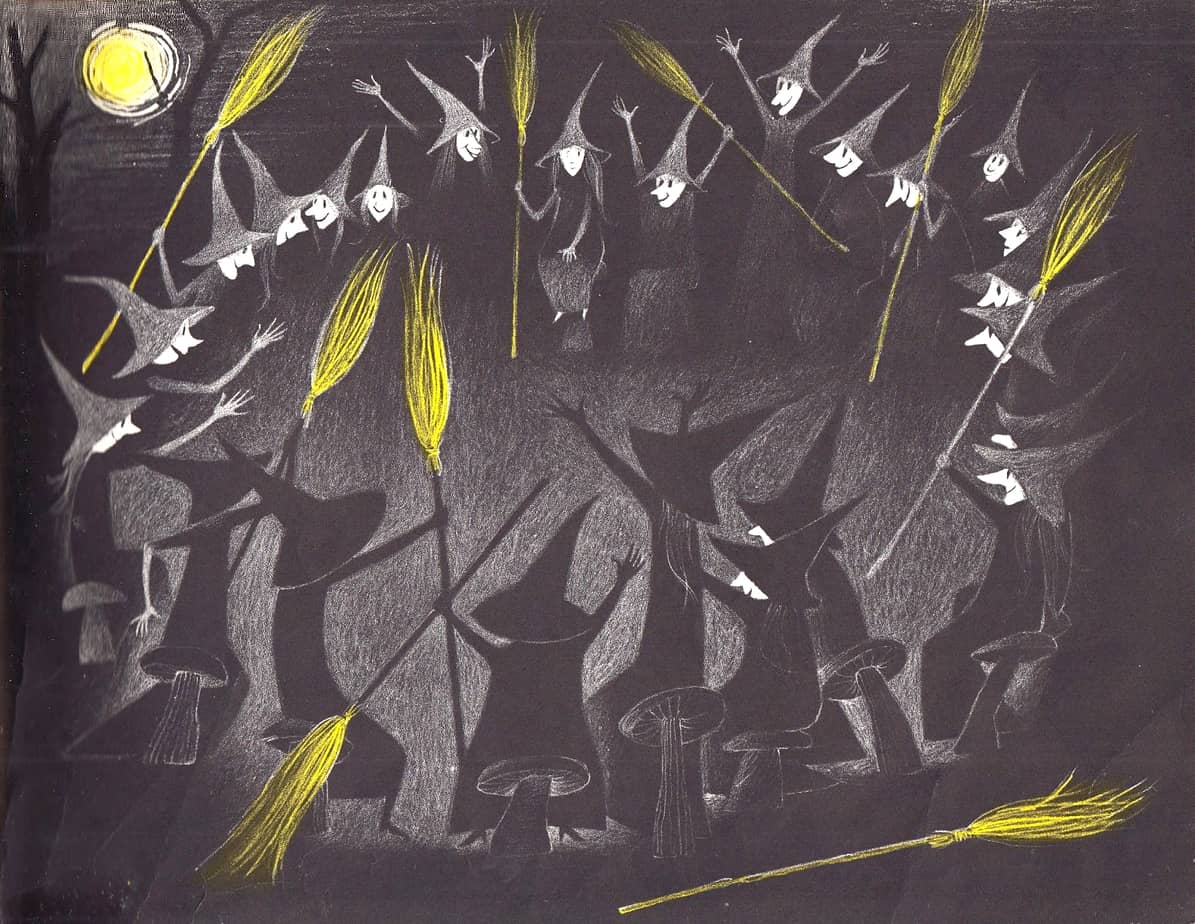

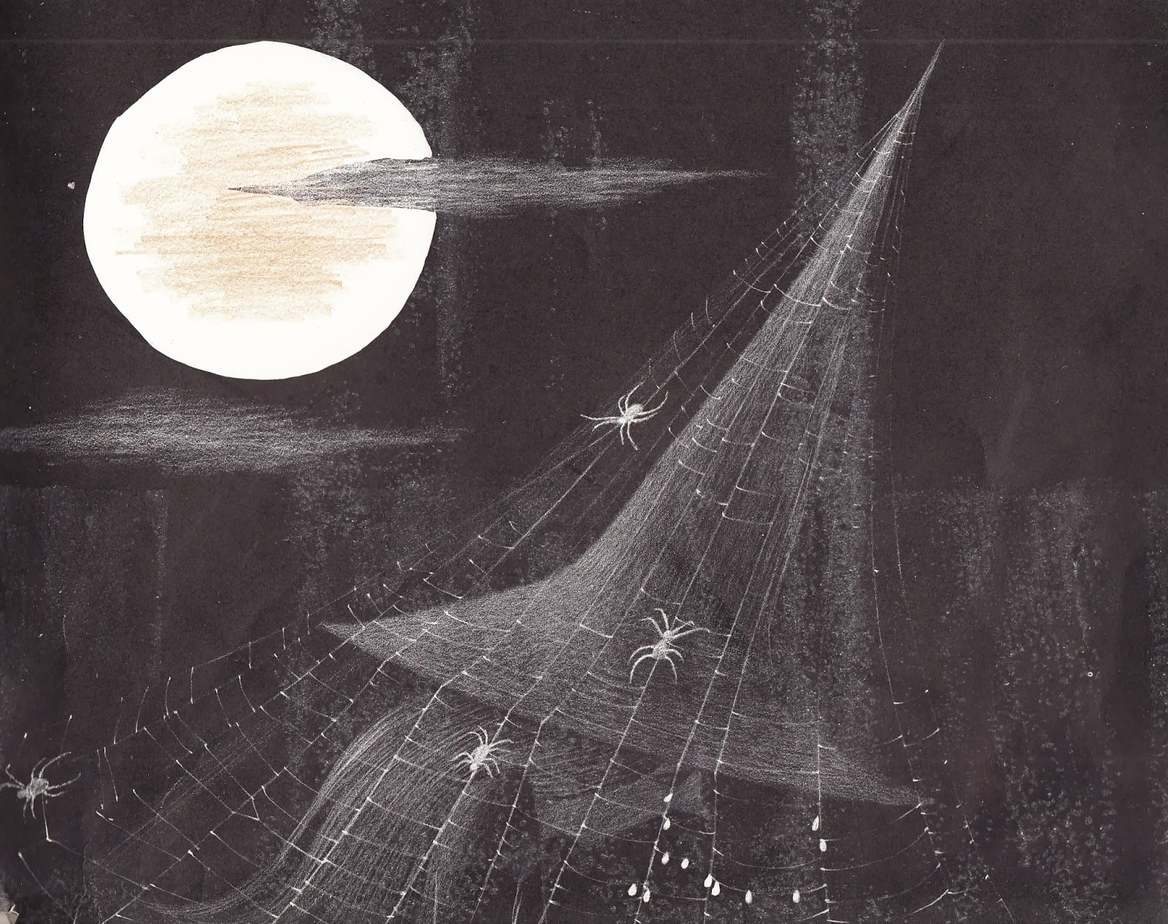

And what did people think witches got up to in the night? They imagined scenes like this one:

Or if she was young, they may have imagined this.

CARNIVALESQUE STORY STRUCTURE OF A WOGGLE OF WITCHES

A Woggle Of Witches has the carnivalesque story structure often seen in children’s picture books. The most popular contemporary carnivalesque stories have a strong reversal or gag at the end, but there is also room on the bookshelf for much quieter versions. This story is at the quiet end of the spectrum.

I’m noticing a gendering of carnivalesque books lately: The carnivalesque stories with the strong gags/reversals tend to feature Every Boys (sometimes with a girl companion), whereas the ‘leaving the house to observe and have fun’ before returning quietly home without incident tends to feature femme characters (in this case, witches). This is no doubt a subconscious carryover from a long tradition of adventure versus domestic stories. ‘Boy’ stories tend to involve battle scenes; ‘girl’ stories tend not to, leading to the new female mythic structure seen in stories such as Inside Out.

An Every Child is at Home

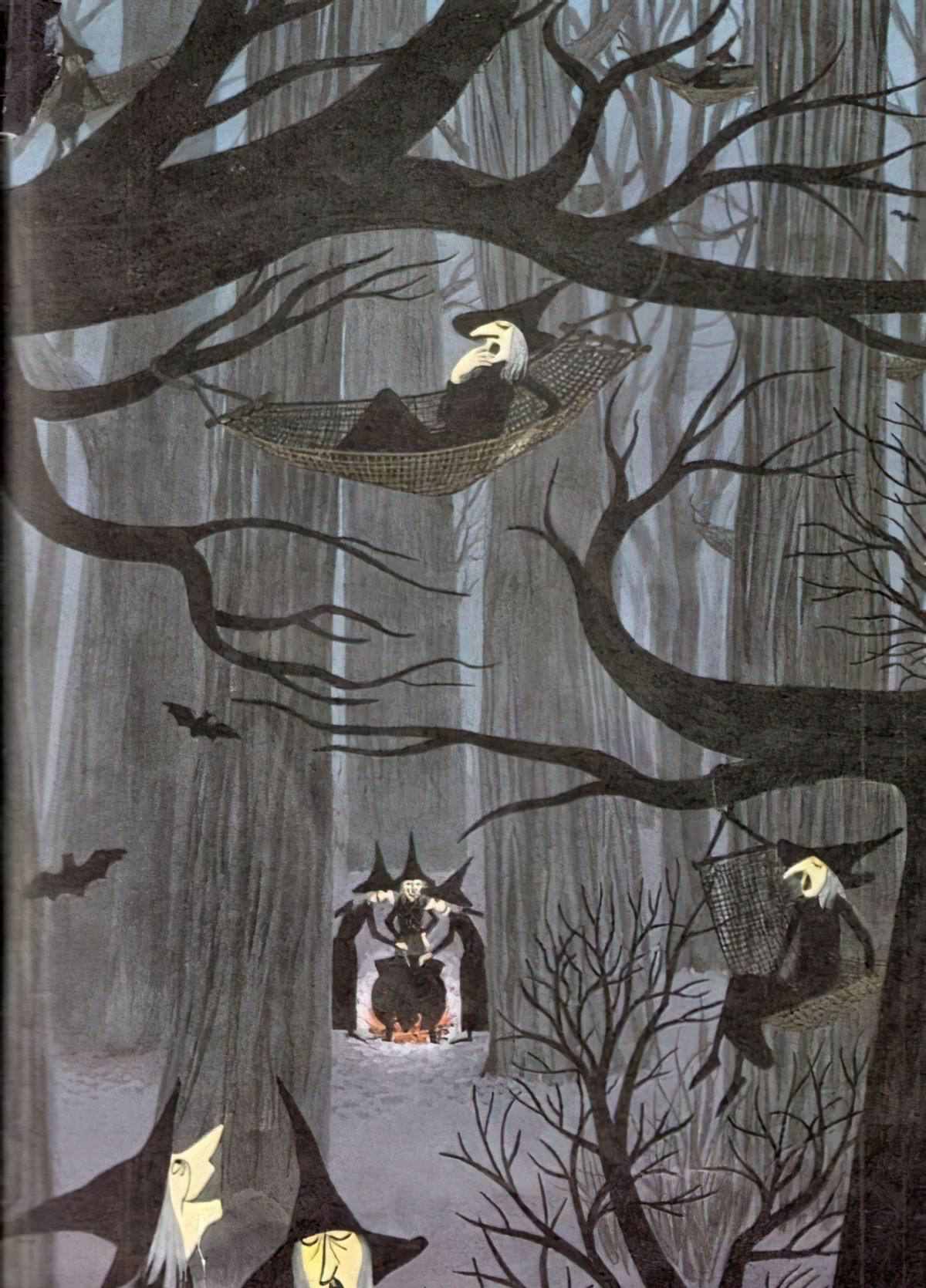

The ‘Every Child’ in this story is a witch, or rather, a whole gaggle (woggle) of unindividuated witches. ‘Home’ is in the dark trees of the forest.

The Every Child wishes to have fun.

After eating bat stew, they decide to ‘leave the dishes’. They need to get going for an adventure clearly based on witch folklore of the witch craze and earlier; it was thought by generations of humans that witches gather at night to carry out their mischief and crime.

I feel ‘leaving the dishes’ is commentary on how these women are eschewing the gender role expected of them. The broomstick itself is a symbol of domestic servitude repurposed to represent freedom.

By the way, doesn’t ‘bat stew’ sound disgusting? I think there may be some natural aversion to eating bats because of their capacity to spread disease between species. Carnivalesque stories quite frequently include some ‘gross out‘ element.

Disappearance or backgrounding of the home authority figure

There is no home authority figure here so this step isn’t necessary. (That’s the advantage to writing child-stand-in characters who are adults.) The witches live in the symbolic forest, on the outskirts of civilised society.

Appearance of an Ally in Fun

This step, too, isn’t necessary. The witches are a swarm, each functioning as an ally in fun for the others. In Adam’s dialogue, we don’t even know which of them is speaking; it doesn’t matter.

Hierarchy is overturned. Fun ensues.

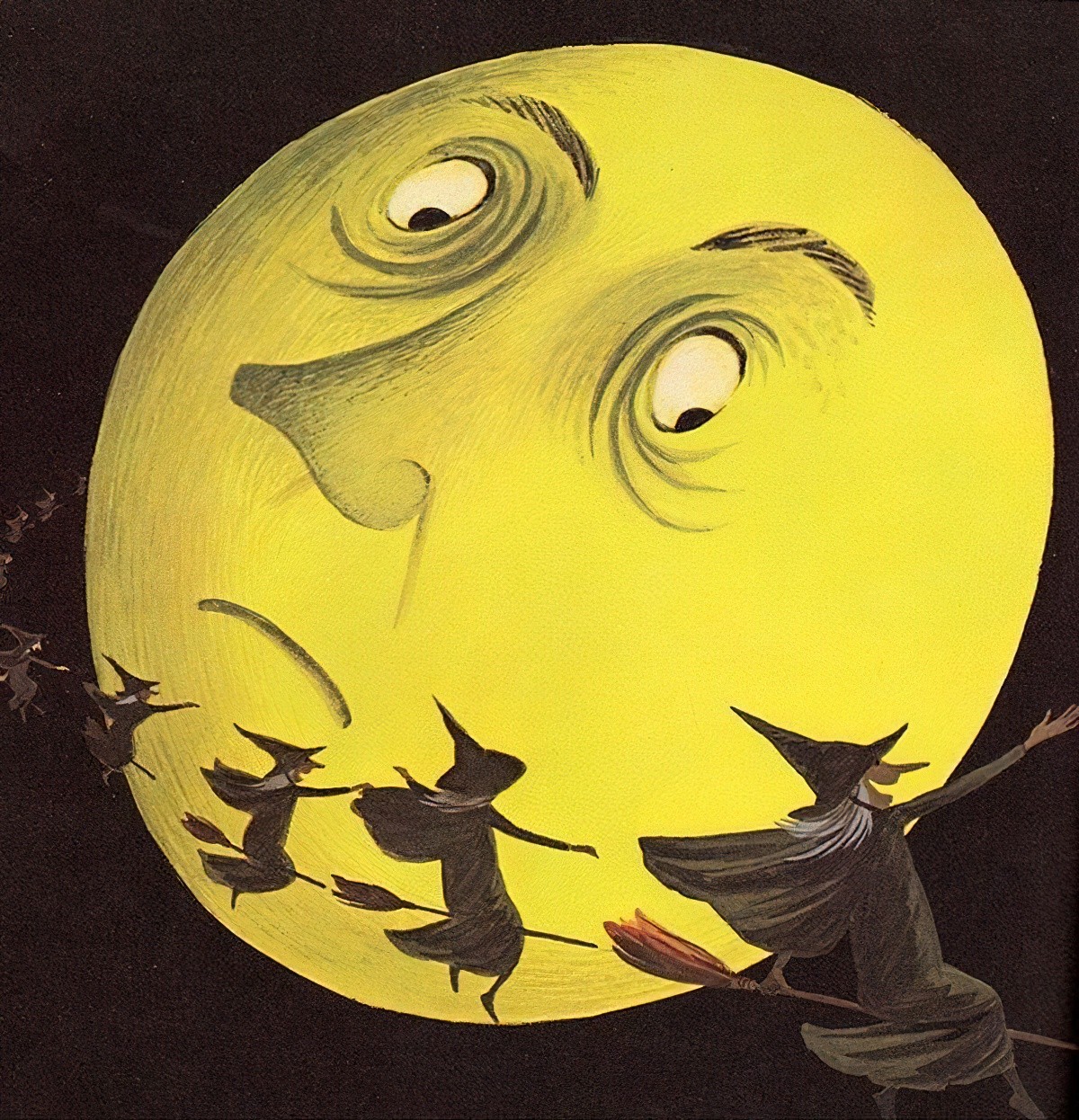

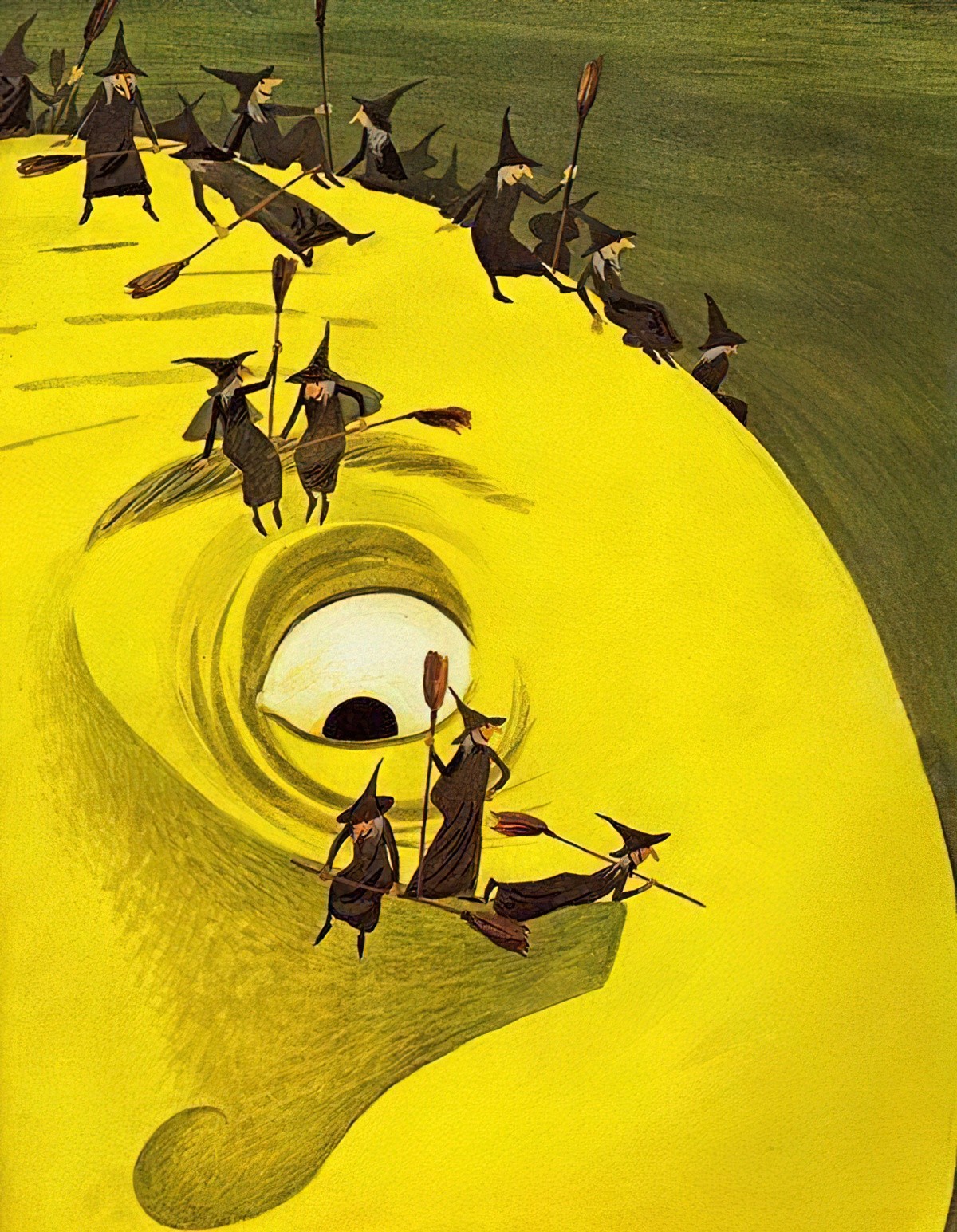

The witches fly up to the moon, which is a face in the sky about the size of a building. The witches form a circle around it, reminiscent of they way children might play in the yard. Many traditional games require standing in a circle. The circle is closely associated with witchery, too.

Fun builds!

“Whee!” This story lets the child reader enjoy the wish fulfilment fantasy of flying. (A common one.) There’s never any threat of falling; one of the witches even stands upright on her broom. They are attached to their brooms by magic.

Peak Fun!

Adams uses several double page spreads to express the fun of the witches. They seem to really enjoy sitting on the face of the moon.

Surprise! (for the reader)

Carnivalesque stories tend to close with a reversal. If not a reversal, then a gag. In this story, the ‘reversal’ is the appearance of the human children (dressed for Halloween). The witches hide from the children, clearly afraid of them. Normally it would be the children afraid of witches. There’s a beautiful frisson of excitement in this reversal as we contemplate the possibility that on the night of Halloween, witches hide in all sorts of places.

Return to the Home state

The story ends with the witches in their treetop beds. “Good night, everybody!” If the child had been scared of witches before, they should now be pacified. Sure, there may be witches hiding in the chimney, or in every nook and cranny, but witches are like spiders; more scared of you than you are of them.

RESONANCE

The children’s book witch is as popular as ever. This witch archetype is far removed from the reality of people deemed witches during the European witch craze (which later spread to America).

What is a woggle?

Adrienne Adams uses the word woggle as a collective noun for witches. Where else might we see it? Woggle: a loop or ring of leather or cord through which the ends of a Scout’s neckerchief are threaded. The word was also used by L. Frank Baum (famous for The Wonderful Wizard of Oz). Like Adams’ picture book, the Baum story illustrated by Ike Morgan in 1905 also features an oversized moon with a face, and a witch who rides on a broom nearby. I wonder if Adams had read The Woggle-Bug Book?