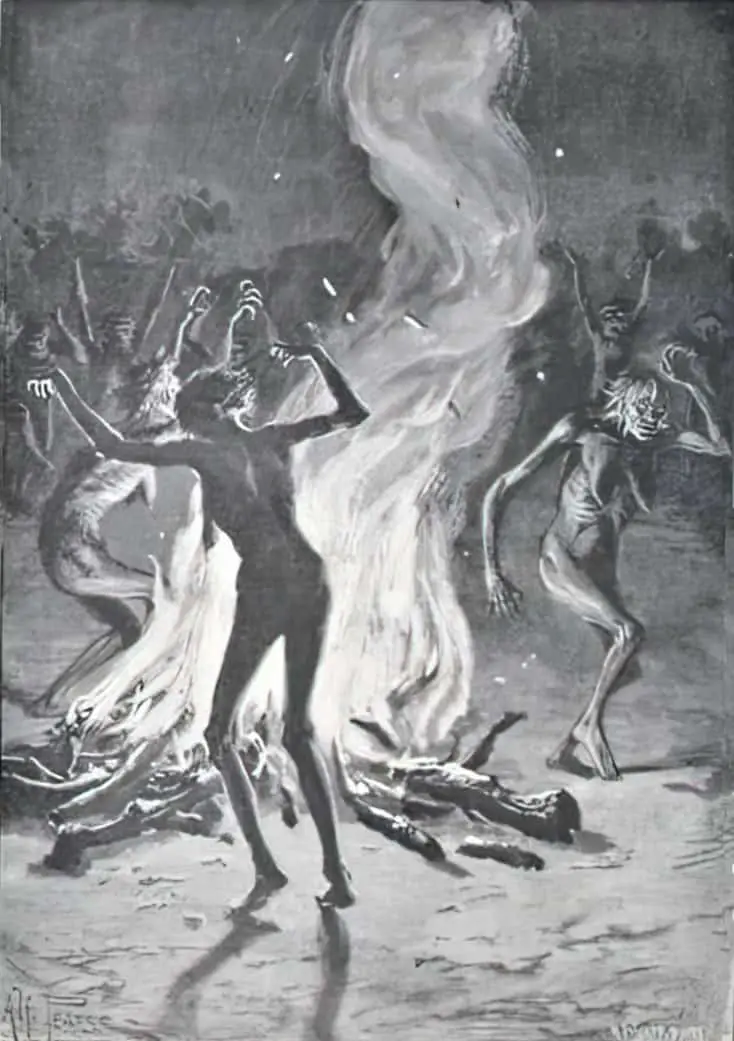

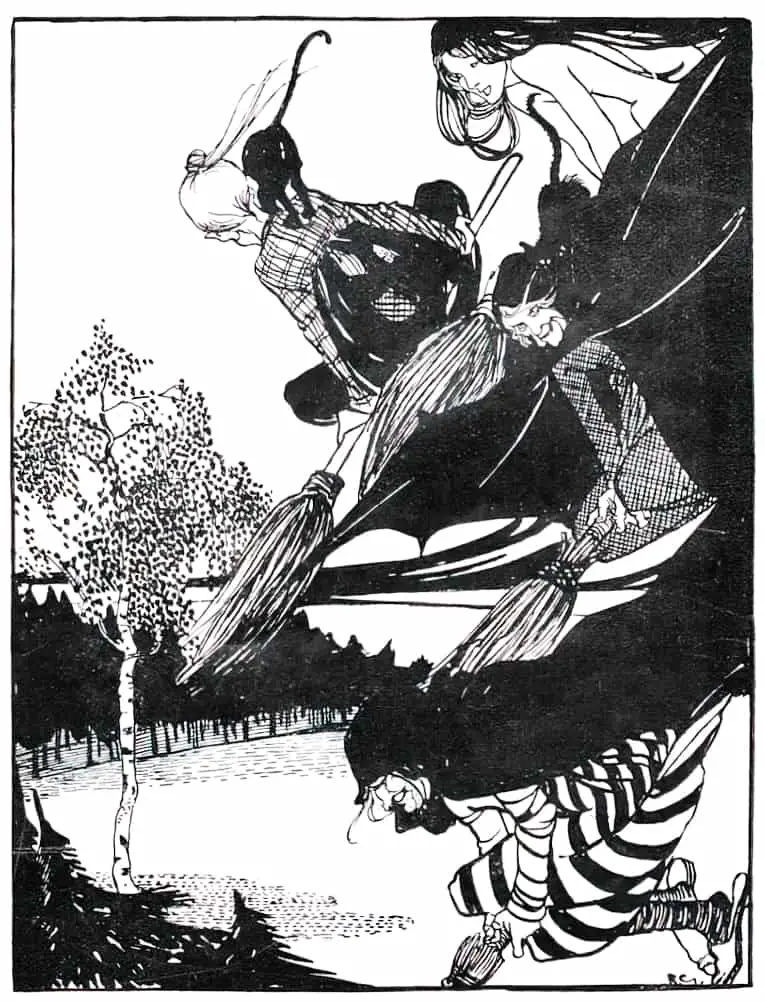

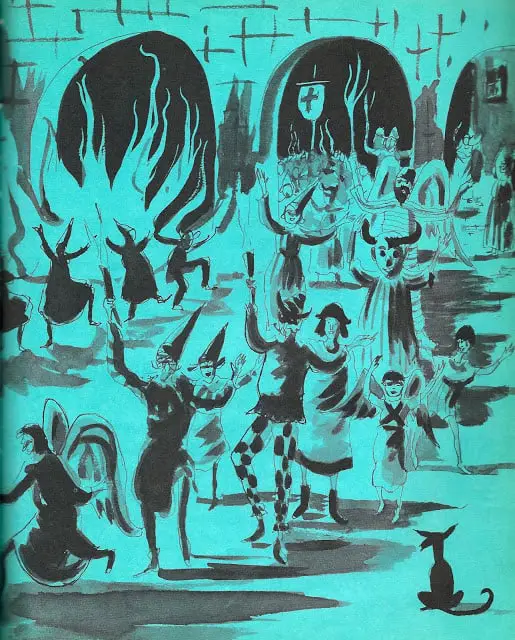

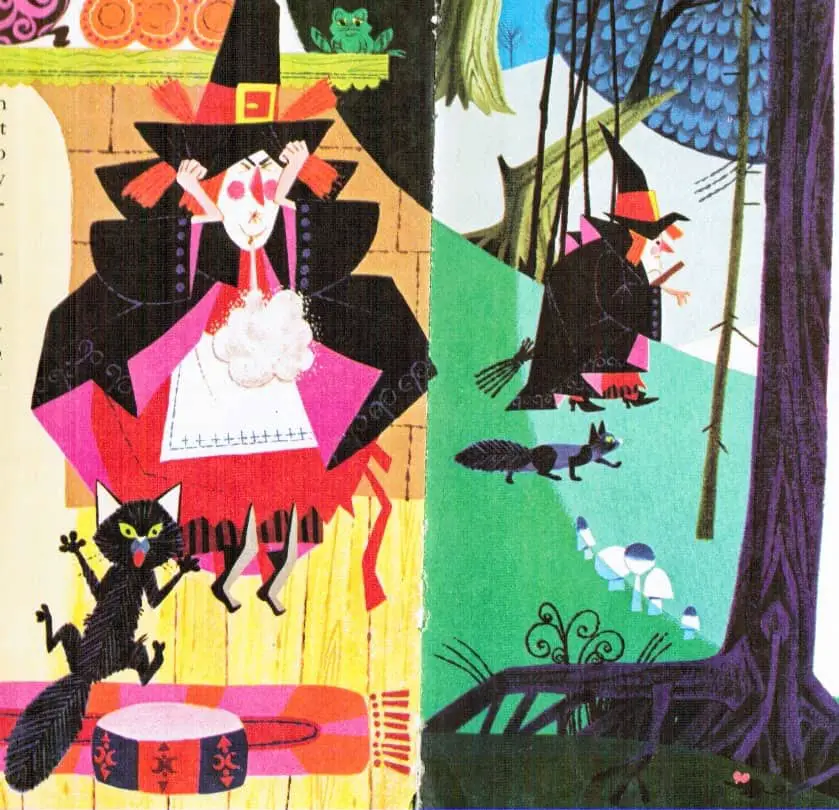

Illustrators frequently depict witches in two mutually exclusive ways: erotic and alluring, or as ugly as the dominant culture can possibly proscribe. Here are some ugly witches dancing around a fire.

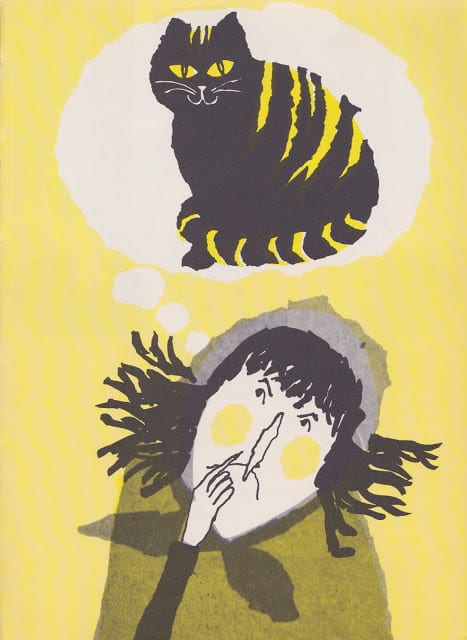

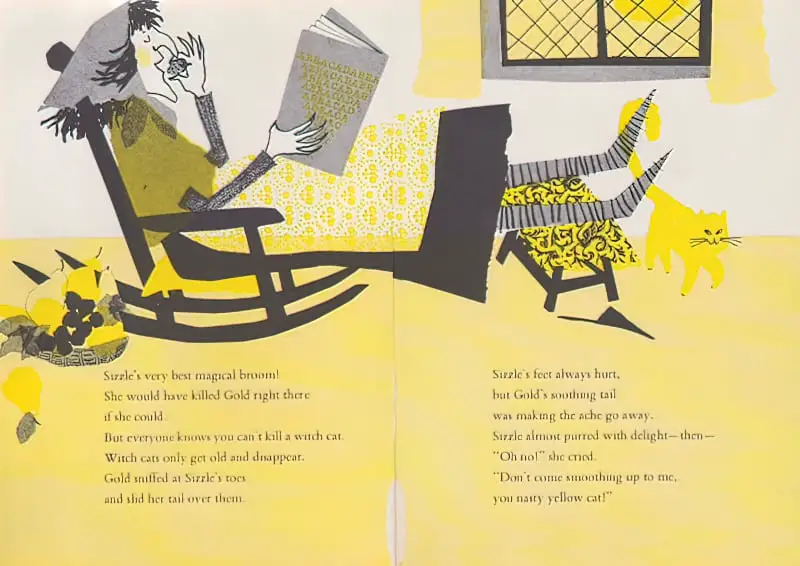

The “Crazy Cat Lady” is a modern day burlesque witch, but you know what they say about crazy ladies. In stories they’re almost always right.

For more on the misogyny, ageism and also racism behind witch persecution, see this post.

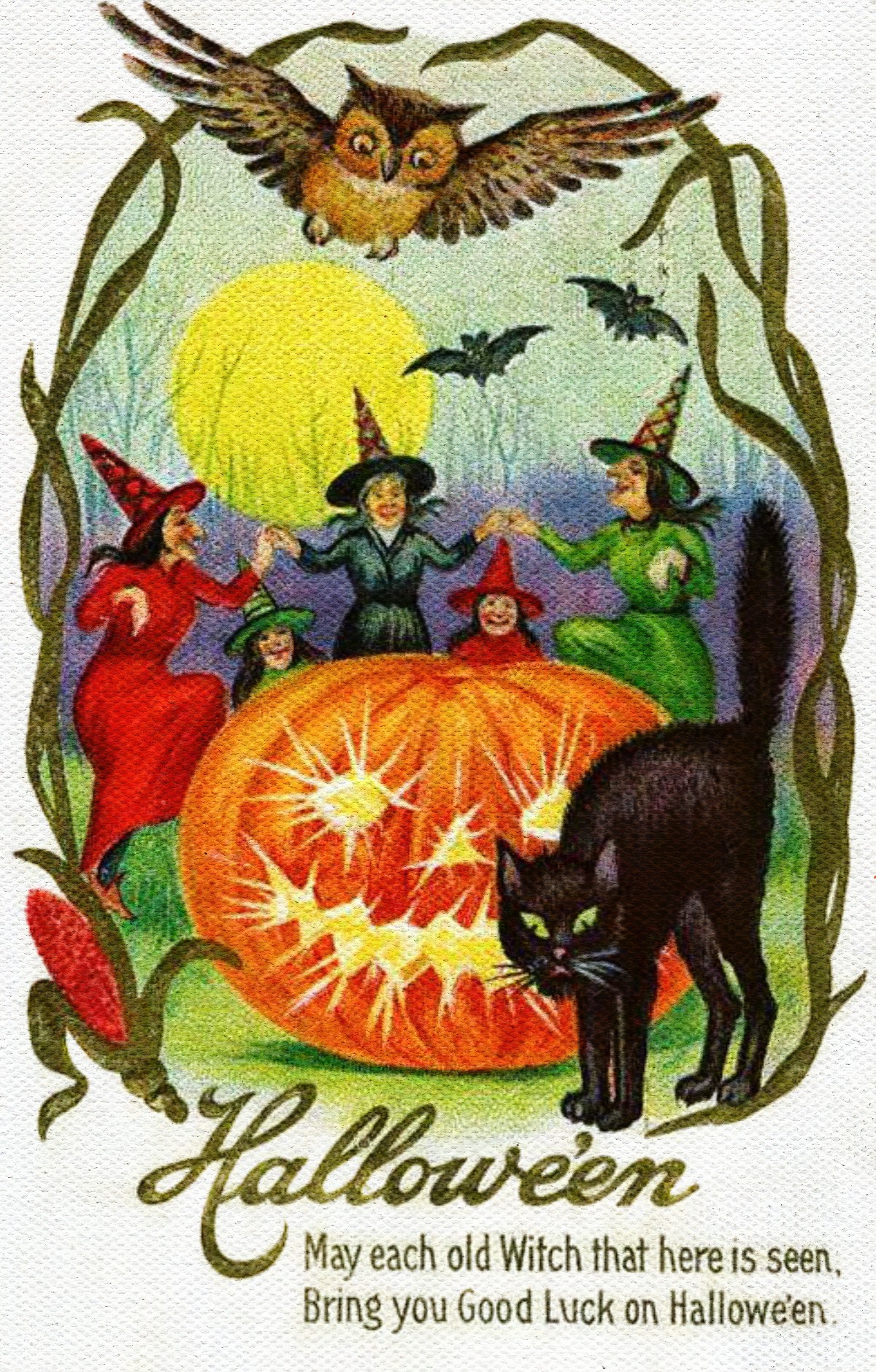

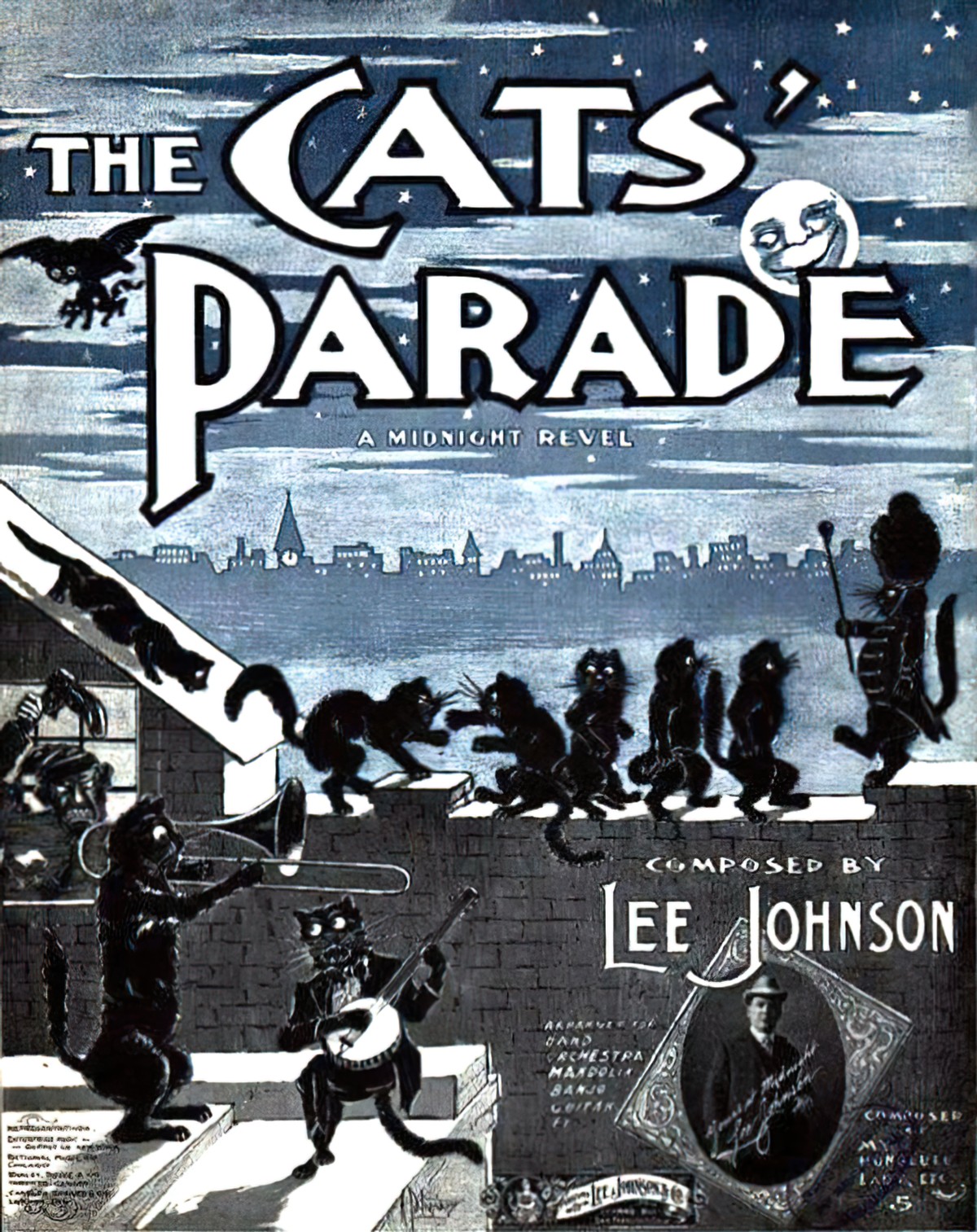

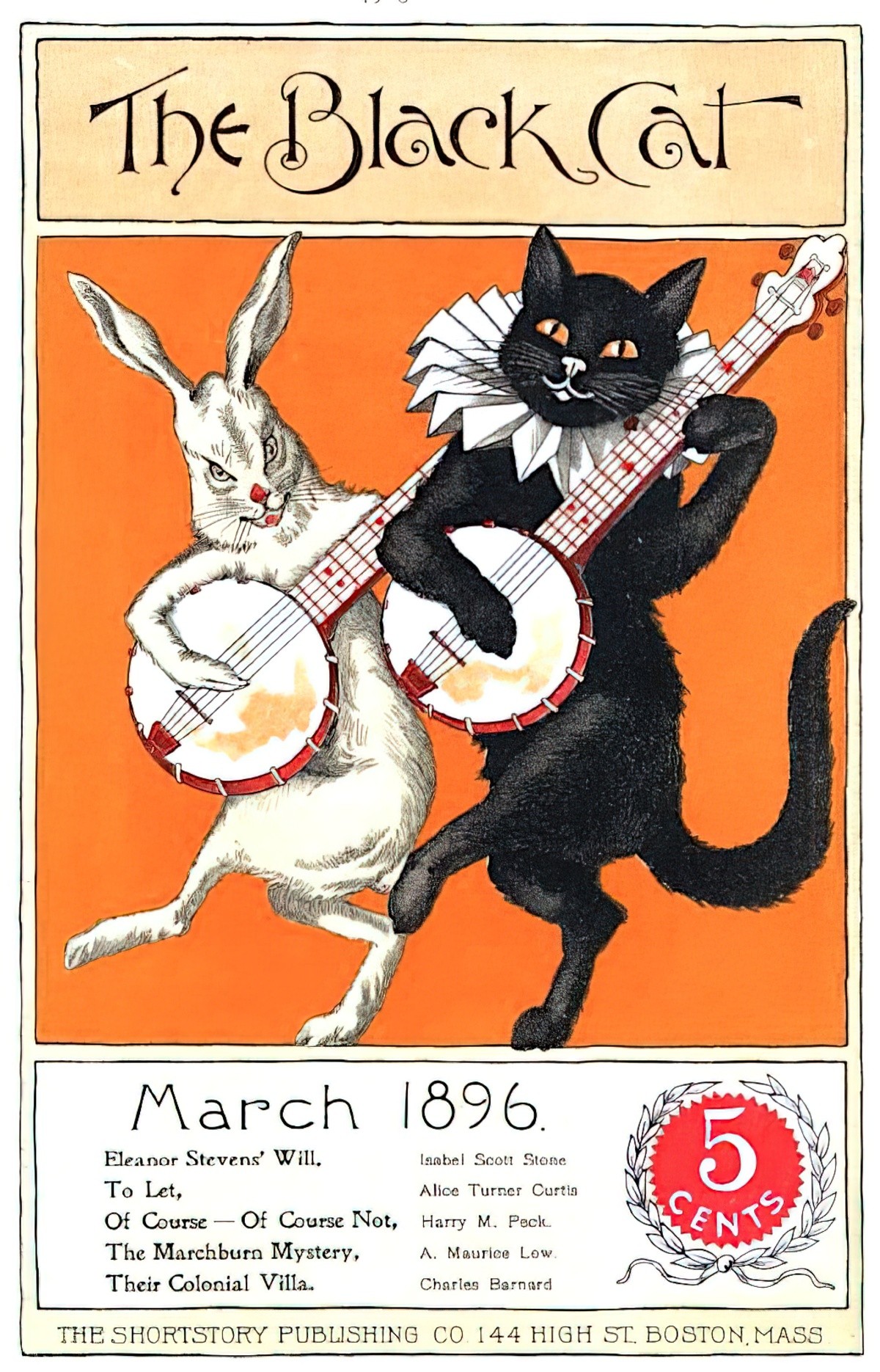

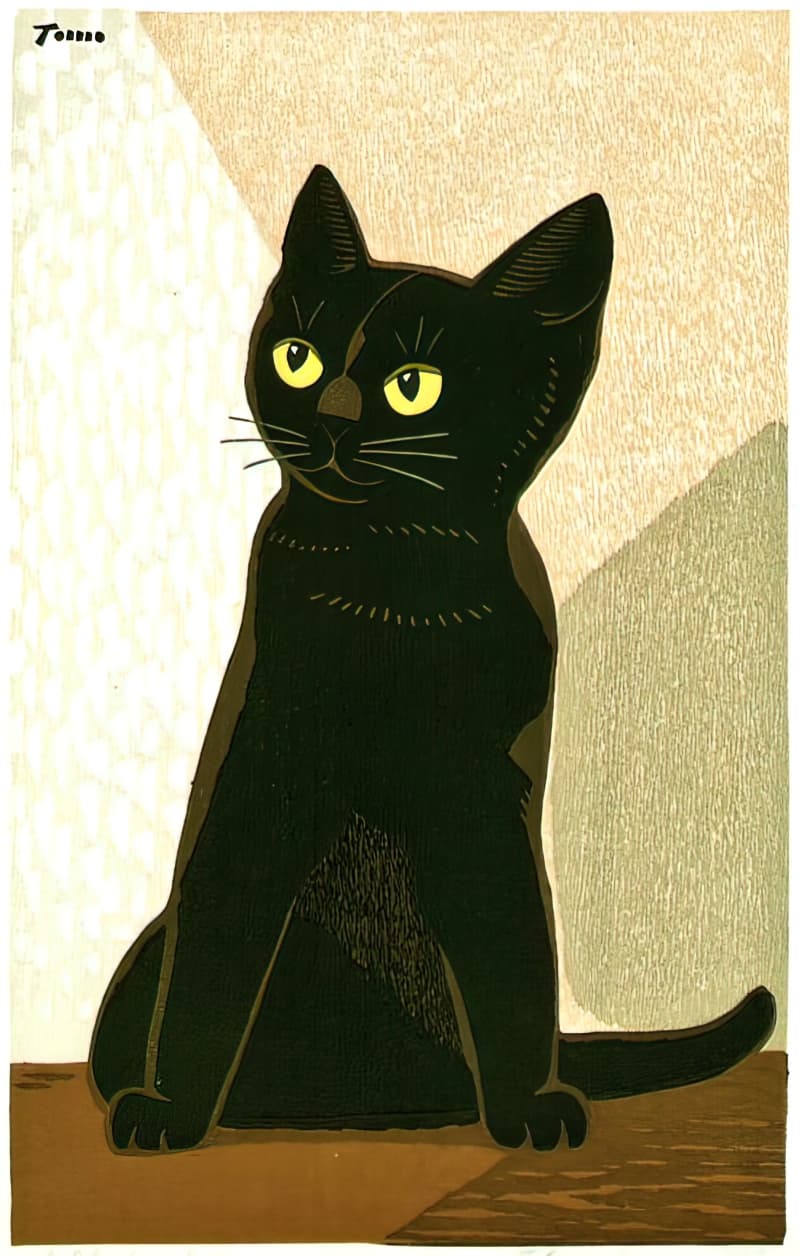

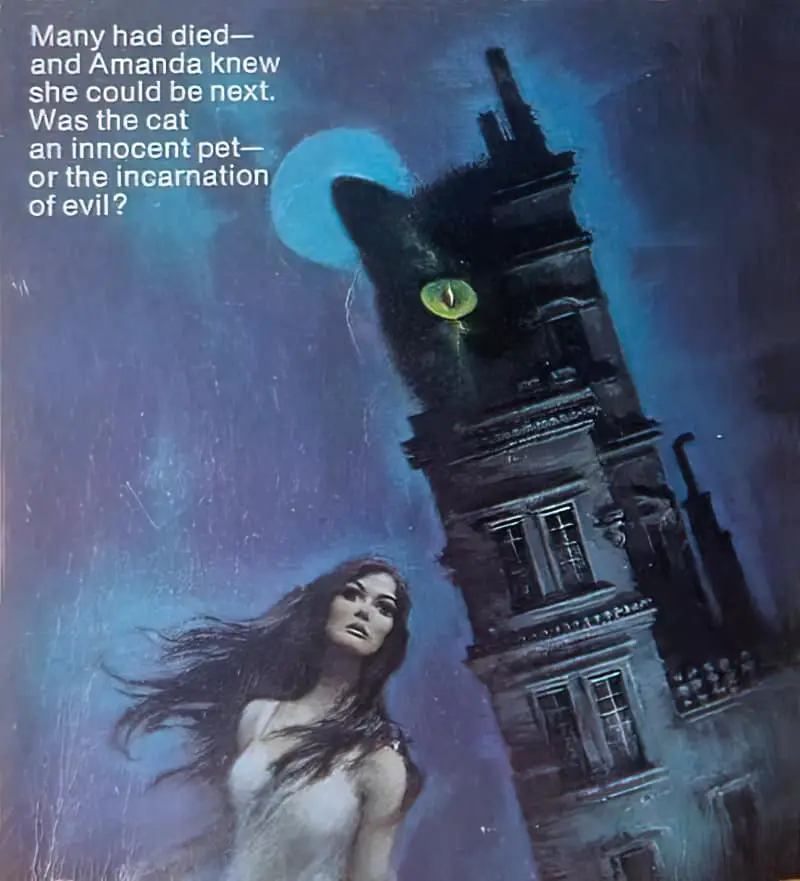

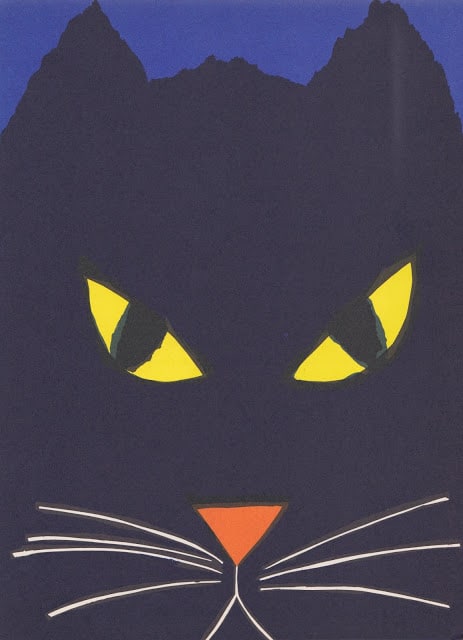

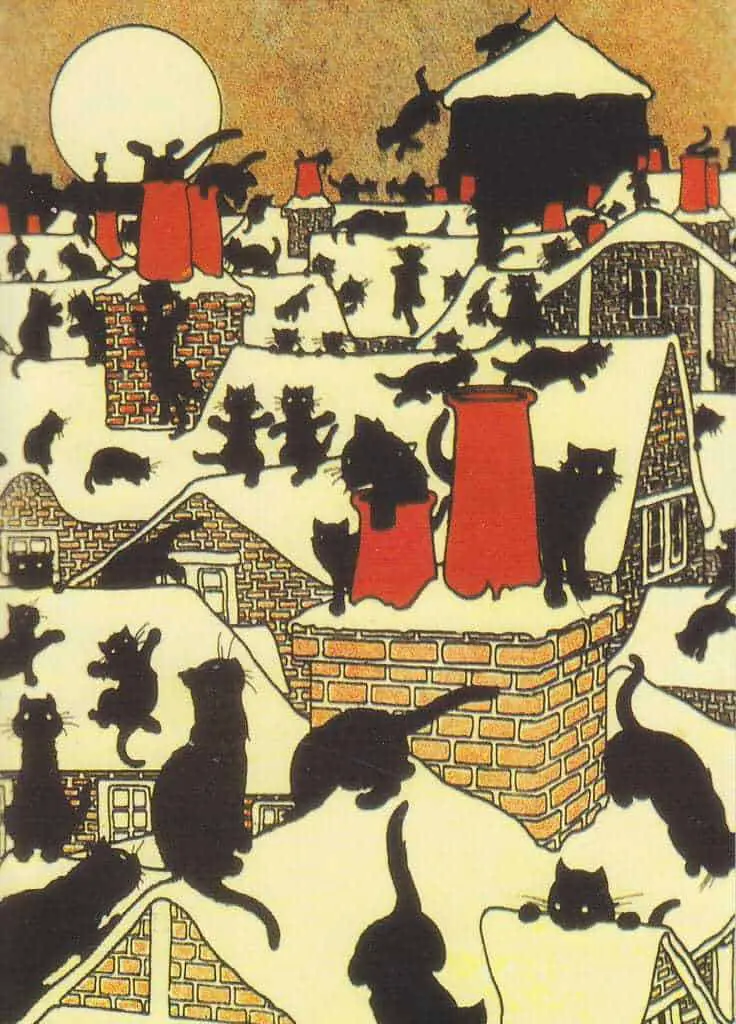

Now for some attention to the witch’s most archetypal familiar: The cat. Like witches themselves, cats can be cute as heck or unappealing as hell.

Not all black cats are witches cats, but all black cats inherit a long tradition of superstition.

A black cat crossing your path signifies that the animal is going somewhere.

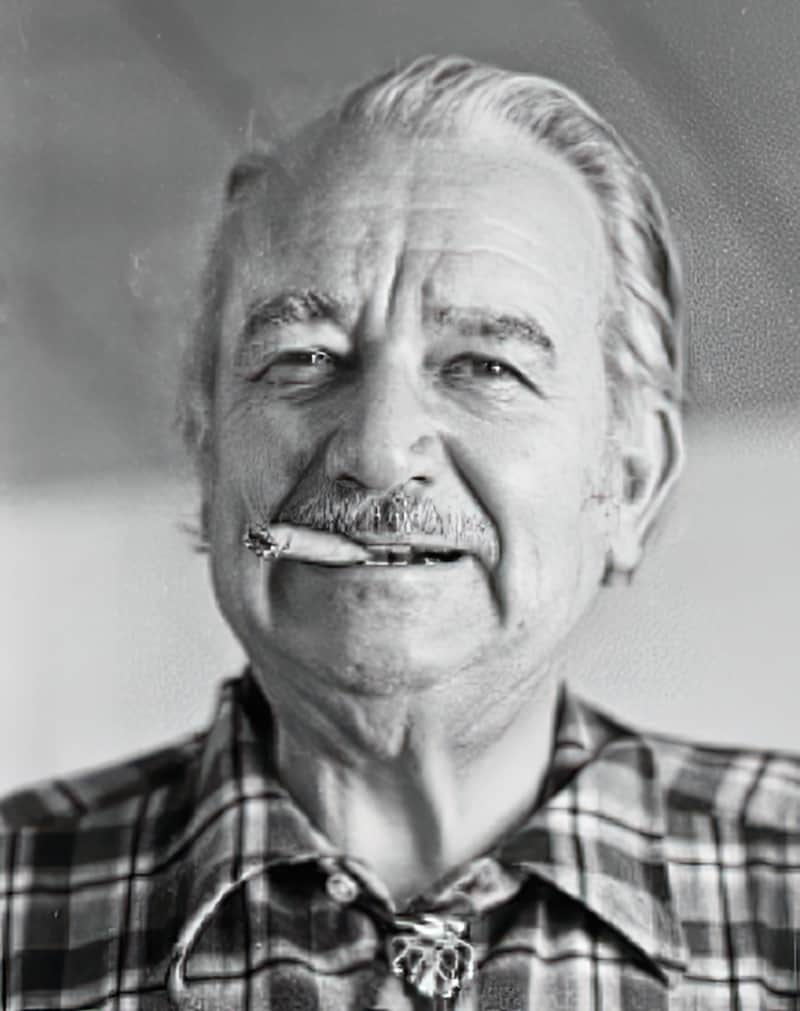

Groucho Marx

In #JapaneseFolklore there are many tales of Cat Witches. These are not witches as we know them in the west, but rather bakeneko (supernatural #yokai cats) that take the form of women in an attempt to lure their victims. Full stories here: https://t.co/LV5HKCMGea#Caturday

In #JapaneseFolklore there are many tales of Cat Witches. These are not witches as we know them in the west, but rather bakeneko (supernatural #yokai cats) that take the form of women in an attempt to lure their victims. Full stories here: https://t.co/LV5HKCMGea#Caturday

To take just one example, on the Scottish Isle of Lewis, witches were infamous for raising storms. One particular wife would disappear each and every night. Eventually her husband decided to follow her. He witnessed her transmogrify into a cat. She then set sail with seven other cats.

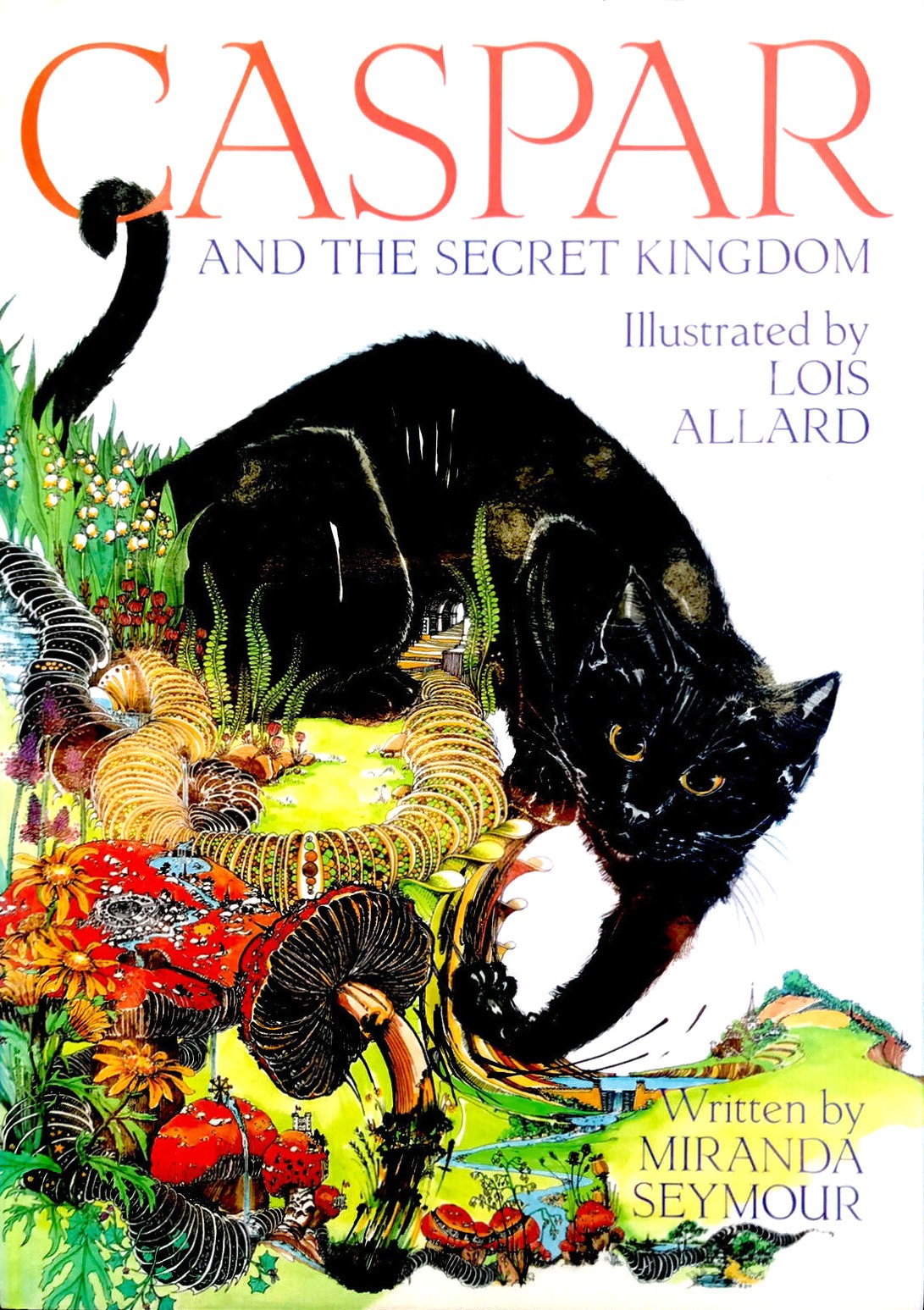

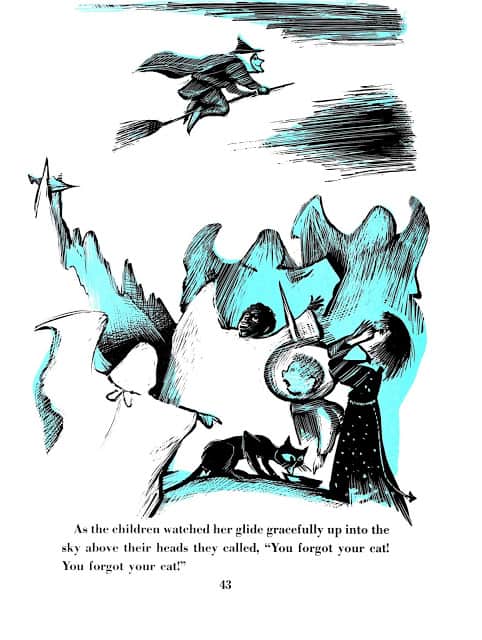

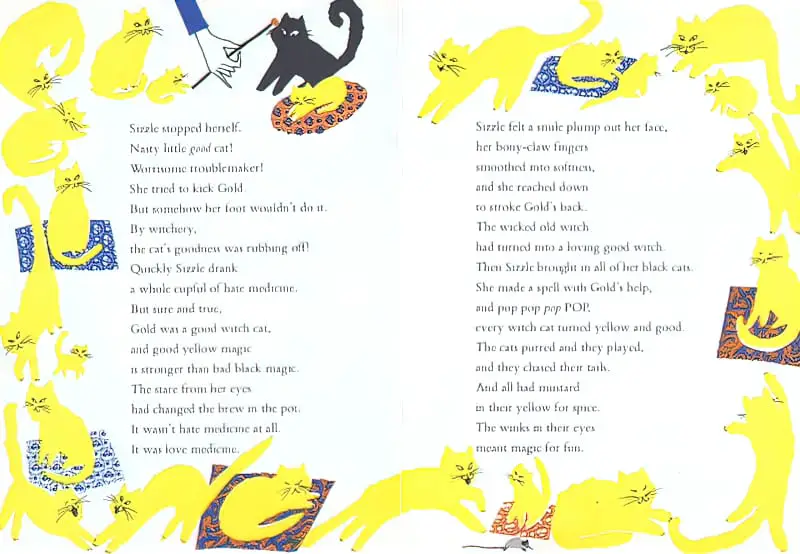

SOME WITCHES’ CATS FROM CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

In the 1959 picture book Space Witch, written and illustrated by Don Freeman, a witch decides to make a space ship and fly to Mars with her cat. (There’s a similar Wallace and Gromit movie, except the pair of them fly to the moon.)

Unfortunately for the cat, once they get to the Milky Way, there’s no actual milk. The cat must go without. The ‘Martians’ on this fictional Mars are identical to human children from America. (Reminds me of the pilot to the original Twilight Zone.)

This witch and her cat try to give the Martians a jump scare, but it doesn’t work. It happens to be Halloween on Mars when they get there.

Fortunately for the cat, someone on Mars gives it cream.

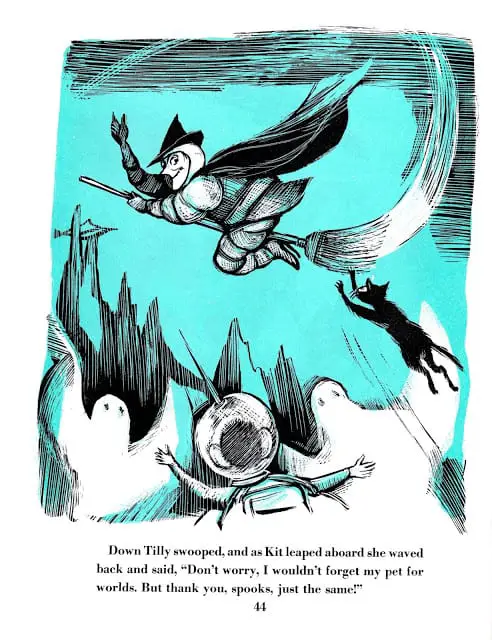

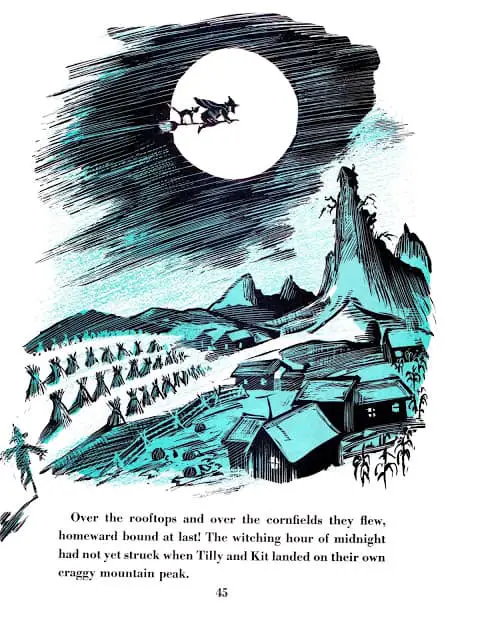

When it’s time to leave the carnivalesque Halloween hi-jinks on Mars, this witch almost forgets her cat. They’ve had enough of rockets and whatnot, so fly back to Earth on her broom.

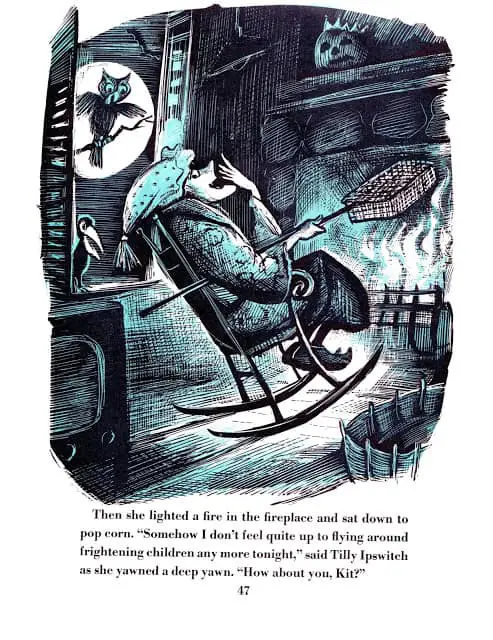

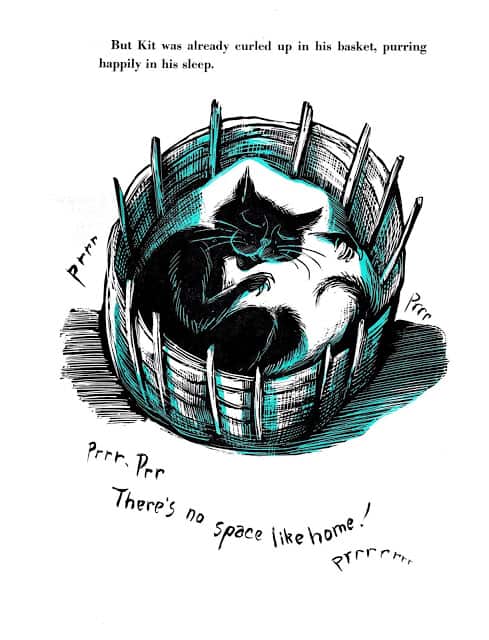

Home-away-home stories for children end with the child character in bed. In this case, the witch sits in front of the hygge hearth, and it is the cat who we see in bed, as child stand-in.

Anthony Meeuwissen, [Cat Falling Off a Broomstick], illustration for The Witch’s Hat, 1973

![Anthony Meeuwissen, [Cat Falling Off a Broomstick], illustration for The Witch's Hat, 1973](https://www.slaphappylarry.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Anthony-Meeuwissen-Cat-Falling-Off-a-Broomstick-illustration-for-The-Witchs-Hat-1973.jpg)

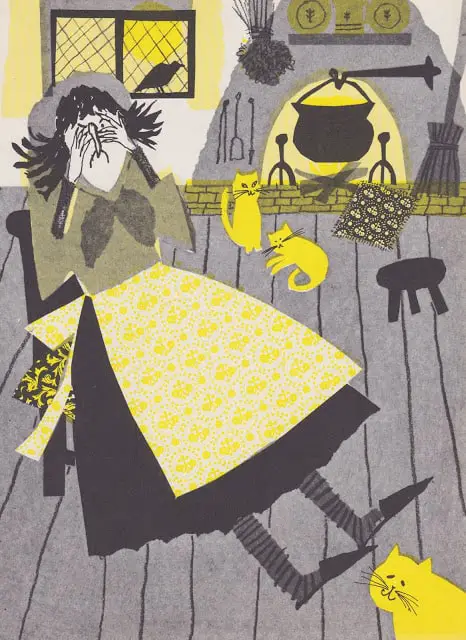

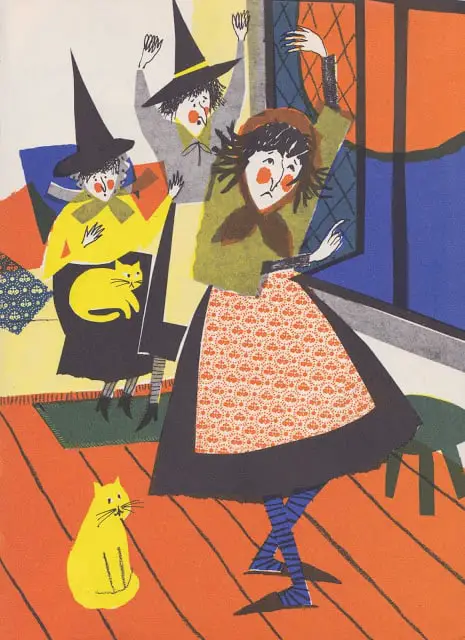

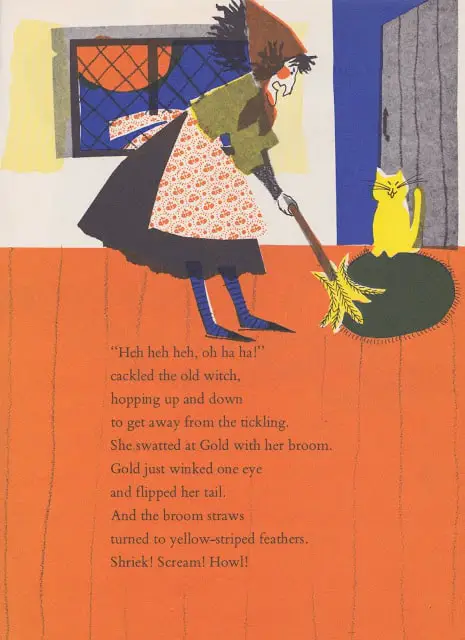

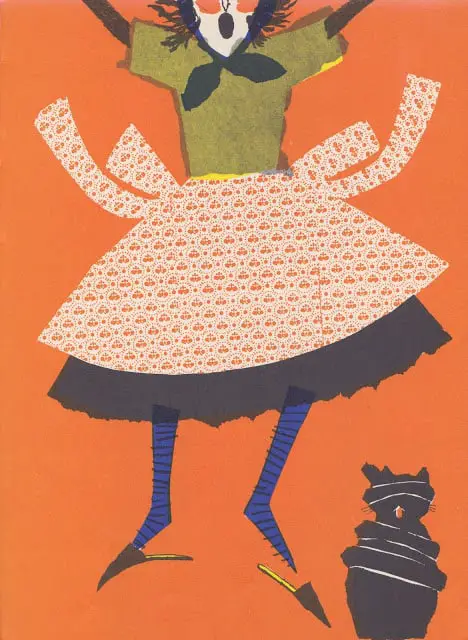

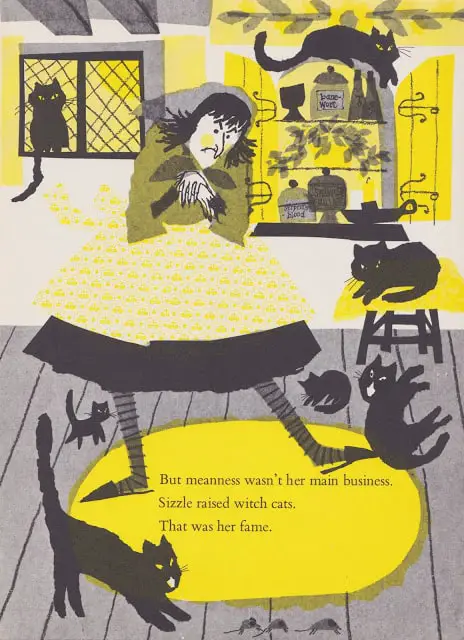

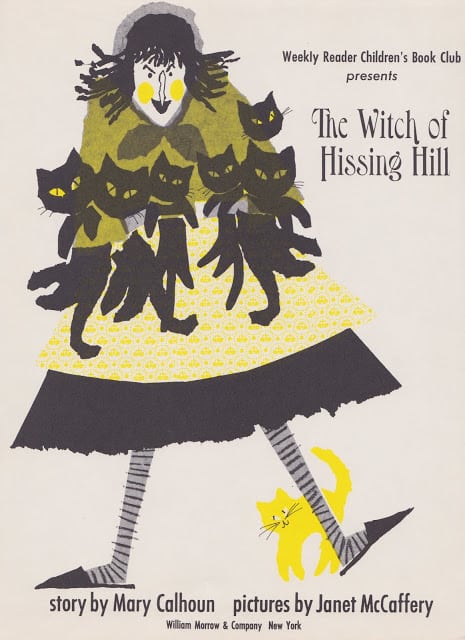

The Witch of Hissing Hill by Mary Calhoun, illustrated by Janet McCaffery (1964)

Halloween A Holiday Book by Lillie Patterson, illustrated by Gil Miret (1963)

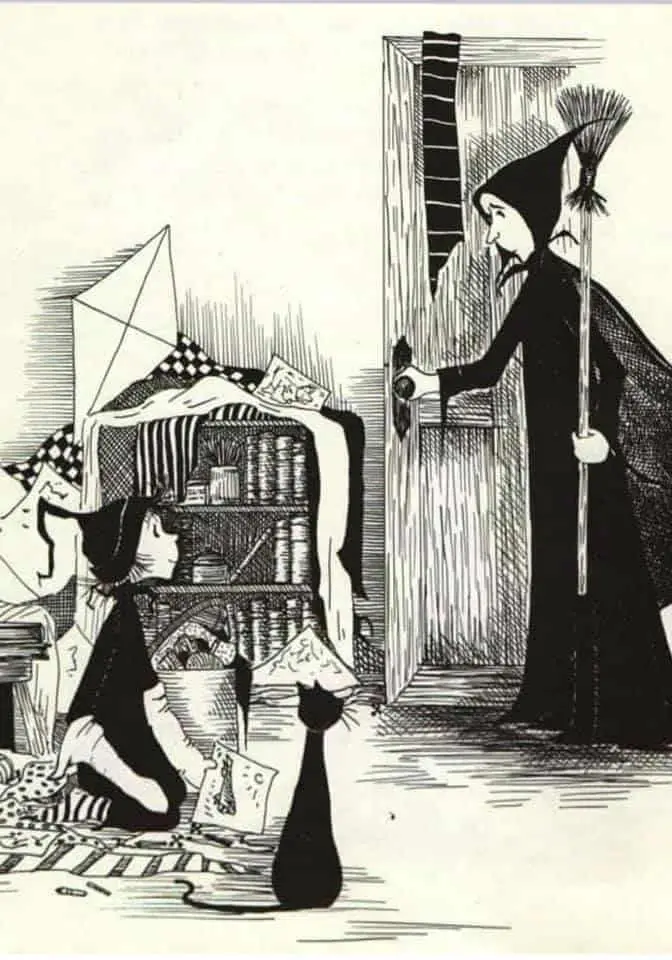

Dorrie the Little Witch by Patricia Coombs

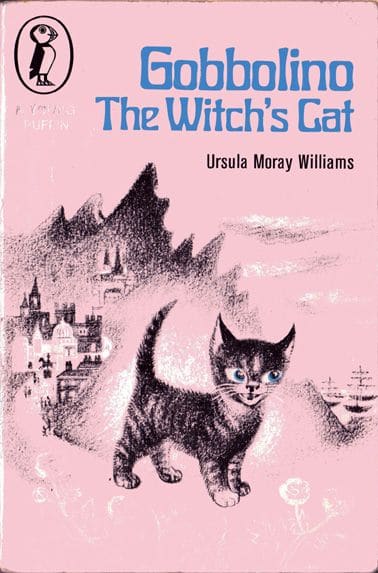

Why was I ever born a witch’s kitten? Why – oh, why? With his bright blue eyes and sparky magic whiskers, no one could mistake Gobbolino for a kitchen cat, but that’s just what he longs to be. So, while his sister Sootica learns how to ride a broomstick and turn mice into toads, Gobbolino sets off to find a nice warm fire and a family to care for him. He has many adventures along the way and makes many friends, until he finally finds the home he dreams of. First published in 1942, Gobbolino the Witch’s Cat continues to delight children – a true modern classic.

The Witch’s Cat by Manly Wade Wellman 1939

Now for a story about an ordinary black cat who becomes a witch’s cat and saves the day.

The Witch’s Cat was first published in Weird Tales Magazine under the penname Gans T. Field. Why you’d want a penname when your real name is Manly Wade Wellman, I don’t even know.

American writer Manly Wade Wellman was born in Portuguese West Africa (now Angola) in 1903. His father was a doctor there. Manly died in 1986 at the age of 83.

OLD JAEL BETTISS, who lived in the hollow among the cypresses, was not a real witch.

It makes no difference that folk thought she was, and walked fearfully wide of her shadow. Nothing can be proved by the fact that she was as disgustingly ugly without as she was wicked within. It is quite irrelevant that evil was her study and profession and pleasure. She was no witch; she only pretended to be.

Jael Bettiss knew that all laws providing for the punishment of witches had been repealed, or at the least forgotten. As to being feared and hated, that was meat and drink to Jael Bettiss, living secretly alone in the hollow.

The house and the hollow belonged to a kindly old villager, who had been elected marshal and was too busy to lock after his property. Because he was easy-going and perhaps a little daunted, he let Jael Bettiss live there rent-free. The house was no longer snug; the back of its roof was broken in, the eaves drooped slackly. At some time or other the place had been

painted brown, before that with ivory black. Now both coats of color peeled away in huge flakes, making the clapboards seem scrofulous. The windows had been broken in every small, grubby pane, and mended with coarse brown paper, so that they were like cast and blurred eyes. Behind was the muddy, bramble-choked back yard, and behind that yawned the old quarry, now abandoned and full of black water. As for the inside—but few ever saw it.

Jael Bettiss did not like people to come into her house. She always met callers on the old cracked doorstep, draped in a cloak of shadowy black, with gray hair straggling, her nose as hooked and sharp as the beak of a buzzard, her eyes filmy and sore-looking, her wrinkle-bordered mouth always grinning and showing her yellow, chisel-shaped teeth.

The near-by village was an old-fashioned place, with stone flags instead of concrete for pavements, and the villagers were the simplest of men and women. From them Jael Bettiss made a fair living, by selling love philtres, or herbs to cure sickness? or charms to ward off bad luck. When she wanted extra money, she would wrap her old black cloak about her and, tramping along a country road, would stop at a cow-pen and ask the farmer what he would do if his cows went dry. The farmer, worried, usually came at dawn next day to her hollow and bought a good-luck charm. Occasionally the cows would go dry anyway, by accident of nature, and their owner would pay more and more, until their milk returned to them.

Now and then, when Jael Bettiss came to the door, there came with her the gaunt black eat, Gib.

Gib was not truly black, any more than Jael Bettiss was truly a witch. He had been born with white markings at muzzle, chest and forepaws, so that he looked to be in full evening dress. Left alone, he would have grown fat and fluffy. But Jael Bettiss, who wanted a fearsome pet, kept all his white spots smeared with thick soot, and underfed him to make him look rakish and lean.

On the night of the full moon, she would drive poor Gib from her door. He would wander to the village in search of food, and would wail mournfully in the yards. Awakened householders would angrily throw boots or pans or sticks of kindling. Often Gib was hit and his cries were sharpened by pain. When that happened, Jael Bettiss took care to be seen next morning with a bandage on head or wrist. Some of the simplest villagers thought that

Gib was really the old woman, magically transformed. Her reputation grew, as did Gib’s unpopularity. But Gib did not deserve mistrust—like all cats, he was a practical philosopher, who wanted to be comfortable and quiet and dignified. At bottom, he was amiable. Like all cats, too, he loved his home above all else; and the house in the hollow, be it ever so humble and often cruel, was home. It was unthinkable to him that he might live elsewhere.

In the village he had two friends—black-eyed John Frey, the storekeeper’s son, who brought the mail to and from the county seat, and Ivy Hill, pretty blond daughter of the town marshal, the same town marshal who owned the hollow and let Jael Bettiss live in the old house. John Frey and Ivy Hill were so much in love with each other that they loved everything else, even black-stained, hungry Gib. He was grateful; if he had been able, Jie would have loved them in return. But his little heart had room for one devotion only, and that was given to the house in the hollow.

ONE day, Jael Bettiss slouched darkly into old Mr. Frey’s store, and up to the counter that served for postoffice. Leering, she gave John Frey a letter. It was directed to a certain little-known publisher, asking for a certain little-known book. Several days letter, she appeared again, received a parcel, and bore it to her home.

In her gloomy, secret parlor, she unwrapped her purchase. It was a small, drab volume, with no title on cover or back. Sitting at the rickety table, she began to read. All evening and most of the night she read, forgetting to give Gib his supper, though he sat hungrily at her feet.

At length, an hour before dawn, she finished. Laughing loudly and briefly, she turned her beak-nose toward the kerosene lamp on the table. From the book she read aloud two words. The lamp went out, though she had not blown at it. Jael Bettiss spoke one commanding word more, and the lamp flamed alight again.

“At last!” she cried out in shrill exultation, and grinned down at Gib. Her lips drew back from her yellow chisels of teeth. “At last!” she crowed again. “Why don’t you speak to me, you little brute? … Why don’t you, indeed?”

She asked that final question as though she had been suddenly inspired. Quickly she glanced through the back part of the book, howled with laughter over something she found there, then sprang up and scuttled like a big, filthy crab into the dark, windowless cell that was her kitchen. There she mingled salt and malt in the palm of her skinny right hand. After that, she rummaged out a bundle of dried herbs, chewed them fine and spat them into the mixture. Stirring again with her forefinger, she returned to the parlor. Scanning the book to refresh her memory, she muttered a nasty little rime. Finally she dashed the mess suddenly upon Gib.

He retreated, shaking himself, outraged and startled. In a comer he sat down, and bent his head to lick the smeared fragments of the mixture away. But they revolted his tongue and palate, and he paused in the midst of this chore, so important to cats; and meanwhile Jael Bettiss yelled,

“Speak!”

Gib crouched and blinked, feeling sick. His tongue came out and steadied his lips. Finally he said: “I want something to eat.”

His voice was small and high, like a little child’s, but entirely understandable. Jael Bettiss was so delighted that she laughed and clapped her bony knees with her hands, in self-applause.

“It worked!” she cried. “No more humbug about me, you understand? I’m a real witch at last, and not a fraud!”

Gib found himself able to understand all this, more clearly than he had ever understood human affairs before. “I want something to eat,” he said again, more definitely than before. “I didn’t have any supper, and it’s nearly—”

“Oh, stow your gab!” snapped his mistress. “This book, crammed with knowledge and strength, that made me able to do it. I’ll never be without it again, and it’ll teach me all the things I’ve only guessed at and mumbled about. I’m a real witch now, I say. And if you don’t think I’ll make those ignorant sheep of villagers realize it—”

Once more she went off into gales of wild, cracked mirth, and threw a dish at Gib. He darted away into a corner just in time and the missile crashed into blue- and-white china fragments against the wall. But Jael Bettiss read aloud from her book an impressive gibberish, and the dish reformed itself on the floor; the bits crept together and joined and the cracks disappeared, as trickling drops of water form into a pool. And finally, when the witch’s twig-like forefinger beckoned, the dish floated upward like a leaf in a breeze and set itself gently back on the table. Gib watched warily.

“That’s small to what I shall do here after,” swore Jael Bettiss.

WHEN next the mail was distributed at the general store, a dazzling stranger appeared. She wore a cloak, an old-fashioned black coat, but its drapery did not conceal the tall perfection of her form. As for her face, it would have stirred interest and admiration in larger and more sophisticated gatherings than the knot of letter-seeking villagers. Its beauty was scornful but inviting, classic but warm, with something in it of Grecian sculpture and Oriental allure. If the nose was cruel, it was straight; if 1 the lips were sullen, they were full; if the forehead was a suspicion low, it was white and smooth. Thick, thunder-black hair swept up from that forehead, and backward to a knot at the neck. The eyes glowed with strange, hot lights, and wherever they turned they pierced and captivated.

People moved away to let her have a clear, sweeping pathway forward to the counter. Until this stranger had entered. Ivy Hill was the loveliest person present; now she looked only modest and fresh and blond in her starched gingham, and worried to boot. As a matter of fact. Ivy Hill’s insides felt cold and topsy-turvy, because she saw how fascinated was the sudden attention of John Frey.

“Is there,” asked the newcomer in a deep, creamy voice, “any mail for me?”

“Wh-what name, ma’am?” asked John Frey, his brown young cheeks turning full crimson.

“Bettiss. Jael Bettiss.”

He began to fumble through the sheaf of envelopes, with hands that shook. “Are you,” he asked, “any relation to the old lady of that name, the one who lives in the hollow?”

“Yes, of a sort.” She smiled a slow, conquering smile. “She’s my—aunt. Yes. Perhaps you see the family resemblance?” Wider and wider grew the smile with which she assaulted John Frey. “If there isn’t any mail,” she went on, “I would like a stamp. A one-cent stamp.”

Turning to his little metal box on the shelf behind, John Frey tore a single green stamp from the sheet. His hand shook still more as he gave it to the customer and received in exchange a copper cent.

There was really nothing exceptional about the appearance of that copper cent. It looked brown and a little worn, with Lincoln’s head on it, and a date—1917. But John Frey felt a sudden glow in the hand that took it, a glow that shot along his arm and into his heart. He gazed at the coin as if he had never seen its like before. And he put it slowly into his pocket, a different pocket from the one in which he usually kept change, and placed another coin in the till to pay for the stamp. Poor Ivy Hill’s blue eyes grew round and down right miserable. Plainly he meant to keep that copper piece as a souvenir. But John Frey gazed only at the stranger, raptly, as though he were suddenly stunned or hypnotized.

The dark, sullen beauty drew her cloak more tightly around her, and moved regally out of the store and away toward the edge of town. As she turned up the brush-hidden trail to the hollow, a change came. Not that her step was less young and free, her figure less queenly, her eyes dimmer or her beauty short of perfect. All these were as they had been; but her expression became set and grim, her body tense and her head high and truculent. It was as though, beneath that young loveliness, lurked an old and evil heart—which was precisely what did lurk there, it does not boot to conceal. But none saw except Gib, the black cat with soot-covered white spots, who sat on the doorstep ‘of the ugly cottage. Jael Bettiss thrust him aside with her foot and entered.

In the kitchen she filled a tin basin from a wooden bucket, and threw into the water a pinch of coarse green powder with an unpleasant smell. As she stirred it in with her hands, they seemed to grow skinny and harsh. Then she threw great palmfuls of the liquid into her face and over her head, and other changes came…

The woman who returned to the front door, where Gib watched with a cat’s apprehensive interest, was hideous old Jael Bettiss, whom all the village knew and avoided.

“He’s trapped,” she shrilled triumphantly. “That penny, the one I soaked for three hours in a love-philtre, trapped him the moment he touched it!” She stumped to the table, and patted the book as though it were a living, lovable thing.

“You taught me,” she crooned to it. “You’re winning me the love of John Frey!” She paused, and her voice grew harsh again. “Why not? I’m old and ugly and queer, but I can love, and John Frey is the handsomest man in the village!”

THE next day she went to the store again, in her new and dazzling person as a dark, beautiful girl. Gib, left alone in the hollow, turned over in his mind the things that he had heard. The new gift of human speech had brought with it, of necessity, a human quality of reasoning; but his viewpoint and his logic were as strongly feline as ever.

Jael Bettiss’ dark love that lured John Frey promised no good to Gib. There would be plenty of trouble, he was inclined to think, and trouble was something that all sensible cats avoided. He was wise now, but he was weak. What could he do against danger? And his desires, as they had been since kittenhood, were food and warmth and a cozy sleeping-place, and a little respectful affection. Just now he was getting none of the four.

He thought also of Ivy Hill. She liked Gib, and often had shown it. If she won John Frey despite the witch’s plan, the two would build a house all full of creature comforts—cushions, open fires, probably fish and chopped liver. Gib’s tongue caressed his soot-stained lips at the savory thought. It would be good to have a home with Ivy Hill and John Frey, if once he was quit of Jael Bettiss…

But he put the thought from him. The witch had never held his love and loyalty. That went to the house in the hollow, his home since the month that he was bom. Even magic had not taught him how to be rid of that cat-instinctive obsession for his own proper dwelling-place. The sinister, strife-sodden hovel would always call and claim him, would draw him back from the warmest fire, the softest bed, the most savory food in the world. Only John Howard Payne could have appreciated Gib’s yearnings to the full, and he died long ago, in exile from the home he loved.

When Jael Bettiss returned, she was in a fine trembling rage. Her real self shone through the glamor of her disguise, like murky fire through a thin porcelain screen.

Gib was on the doorstep again, and tried to dodge away as she came up, but her enchantments, or something else, had made Jael Bettiss too quick even for a cat. She darted out a hand and caught him by the scruff of the neck.

“Listen to me,” she said, in a voice as deadly as the trickle of poisoned water. “You understand human words. You can talk, and you can hear what I say. You can do what I say, too.” She shook him, by way of emphasis. “Can’t you do what I say?”

“Yes,” said Gib weakly, convulsed with fear.

“All right, I have a job for you. And mind you do it well, or else—” She broke off and shook him again, letting him imagine what would happen if he disobeyed.

“Yes,” said Gib again, panting for breath in her tight grip. “What’s it about?”

“It’s about that little fool, Ivy Hill. She’s not quite out of his heart… Go to the village tonight,” ordered Jael Bettiss, “and to the house of the marshal. Steal something that belongs to Ivy Hill.”

“Steal something?”

“Don’t echo me, as if you were a silly parrot.” She let go of him, and hurried back to the book that was her constant study. “Bring me something that Ivy Hill owns and touches—and be back here with it before dawn.”

Gib carried out her orders. Shortly after sundown he crept through the deepened dusk to the home of Marshal Hill. Doubly black with the soot habitually smeared upon him by Jael Bettiss, he would have been almost invisible, even had anyone been on guard against his coming. But nobody watched; the genial old man sat on the front steps, talking to his daughter.

“Say,” the father teased, “isn’t young Johnny Frey coming over here tonight, as usual?”

“I don’t know, daddy,” said Ivy Hill wretchedly.

“What’s that daughter?” The marshal sounded surprised. “Is there anything gone wrong between you two young ’uns?”

“Perhaps not, but—oh, daddy, there’s a new girl come to town—”

And Ivy Hill burst into tears, groping dolefully on the step beside her for her little wadded handkerchief. But she could not find it.

For Gib, stealing near, had caught it up in his mouth and was scampering away toward the edge of town, and beyond to the house in the hollow.

MEANWHILE, Jael Bettiss worked hard at a certain project of wax modeling. Any witch, or student of witchcraft, would have known at once why she did this.

After several tries, she achieved something quite interesting and even clever—a little female figure, that actually resembled Ivy Hill.

Jael Bettiss used the wax of three candles to give it enough substance and proportion. To make is more realistic, she got some fresh, pale-gold hemp, and of this made hair, like the wig of a blond doll, for the wax head. Drops of blue ink served for eyes, and a blob of berry-juice for the red mouth. All the while she worked, Jael Bettiss was muttering and mumbling words and phrases she had gleaned from the rearward pages of her book.

When Gib brought in the handkerchief, Jael Bettiss snatched it from his mouth, with a grunt by way of thanks. With rusty scissors and coarse white thread, she fashioned for the wax figure a little dress. It happened that the handkerchief was of gingham, and so the garment made all the more striking the puppet’s resemblance to Ivy Hill.

“You’re a fine one!” tittered the witch, propping her finished figure against the lamp. “You’d better be scared!”

For it happened that she had worked into the waxen face an expression of terror. The blue ink of the eyes made wide round blotches, a stare of agonized fear; and the berry-juice mouth seemed to tremble, to plead shakily for mercy.

Again Jael Bettiss refreshed her memory of goetic spells by poring over the back of the book, and after that she dug from the bottom of an old pasteboard box a handful of rusty pins. She chuckled over them, so that one would think triumph already hers. Laying, the puppet on its back, so that the lamplight fell full upon it, she began to recite a spell.

“I have made my wish before,” she said in measured tones. “I will make it now. And there was never a day that I did not see my wish fulfilled.” Simple, vague—but how many have died because those words were spoken in a certain way over images of them?

The witch thrust a pin into the breast of the little wax figure, and drove it all the way in, with a murderous pressure of hex thumb. Another pin she pushed into the head, another into an arm, another into a leg; and so on, until the gingham-clad pup pet was fairly studded with transfixing pins.

“Now,” she said, “we shall see what we shall see.”

Morning dawned, as dear and golden as though wickedness had never been born into the world. The mysterious new paragon of beauty—not a young man of the village but mooned over her, even though she was the reputed niece and namesake of that unsavory old vagabond, Jael Bettiss—walked into the general store to make purchases. One delicate pink ear turned to the gossip of the housewives.

Wasn’t it awful, they were agreeing, how poor little Ivy Hill was suddenly sick almost to death—she didn’t seem to know her father or her friends. Not even Doctor Melcher could find out what was the matter with her. Strange that John Frey was not interested in her troubles; but John Frey sat behind the counter, slumped on his stool like a mud idol, and his eyes lighted up only when they spied lovely young Jael Bettiss with her market basket.

When she had heard enough, the witch left the store and went straight to the town marshal’s house. There she spoke gravely and sorrowfully about how she feared for the sick girl, and was allowed to visit Ivy Hill in her bedroom. To the Father and the doctor, it seemed that the patient grew stronger and felt less pain while Jael Bettiss remained to wish her a quick recovery; but, not long after this new acquaintance departed, Ivy Hill grew worse, She fainted, and recovered only to vomit.

And she vomited—pins, rusty pins. Something like that happened in old Salem Village, and earlier still in Scotland, before the grisly cult of North Berwick was literally burned out. But Doctor Melcher, a more modern scholar, had never seen or heard of anything remotely resembling Ivy Hill’s disorder.

So it went, for three full days. Gib, too, heard the doleful gossip as he slunk around the village to hunt for food and to avoid Jael Bettiss, who did not like him near when she did magic. Ivy Hill was dying, and he mourned her, as for the boons of fish and fire and cushions and petting that might have been his. He knew, too, that he was responsible for her doom and his loss—that handkerchief that he had stolen had helped Jael Bettiss to direct her spells.

But philosophy came again to his aid. If Ivy Hill died, she died. Anyway, he had never been given the chance to live as her pensioner and pet. He was not even sure that he would have taken the chance—thinking of it, he felt strong, accustomed clamps upon his heart. The house in the hollow was his home forever. Elsewhere he’d be an exile.

Nothing would ever root it out of his feline soul.

ON THE evening of the third day, witch and cat faced each other across the table-top in the old house in the hollow.

“They’ve talked loud enough to make his dull ears hear,” grumbled the fearful old woman—with none but Gib to see her, she had washed away the disguising enchantment that, though so full of lure, seemed to be a burden upon her. “John Frey has agreed to take Ivy Hill out in his automobile. The doctor thinks that the fresh air, and John Frey’s company, will make her feel better—but it won’t. It’s too late. She’ll never return from that drive.”

She took up the pin-pierced wax image of her rival, rose and started toward the kitchen.

“What are you going to do?” Gib forced himself to ask.

“Do?” repeated Jael Bettiss, smiling murderously. “I’m going to put an end to that baby-faced chit—but why are you so curious? Get out, with your prying!”

And, snarling curses and striking with her claw-like hands, she made him spring down from his chair and run out of the house. The door slammed, and he crouched in some brambles and watched. No sound, and at the half-blinded windows no movement; but, after a time, smoke began to coil upward from the chimney. Its first puffs, were dark and greasy-looking. Then it turned dull gray, then white, then blue as indigo. Finally it vanished altogether.

When Jael Bettiss opened the door and came out, she was once more in the semblance of a beautiful dark girl. Yet Gib recognized a greater terror about her than ever before.

“You be gone from here when I get back,” she said to him.

“Gone?” stammered Gib, his little heart turning cold. “What do you mean?”

She stooped above him, like a threatening bird of prey.

“You be gone,” she repeated. “If I ever see you again. I’ll kill you—or I’ll make my new husband kill you.”

He still could not believe her. He shrank back, and his eyes turned mournfully to the old house that was the only thing he loved.

“You’re the only witness to the things I’ve done,” Jael Bettiss continued. “Nobody would believe their ears if a cat started telling tales, but anyway, I don’t want any trace of you around. If you leave, they’ll forget that I used to be a witch. So run!”

She turned away. Her mutterings were now only her thoughts aloud: “If my magic works — and it always works—that car will find itself idling around through the hill road to the other side of the quarry. John Frey will stop there. And so will Ivy Hill—forever.”

Drawing her cloak around her, she stalked purposefully toward the old quarry behind the house.

LEFT by himself, Gib lowered his lids and let his yellow eyes grow dim and deep with thought. His shrewd beast’s mind pawed and probed at this final wonder and danger that faced him and John Frey and Ivy Hill.

He must run away if he would live. The witch’s house in the hollow, that had never welcomed him, now threatened him. No more basking on the doorstep, no more ambushing wood-mice among the brambles, no more dozing by the kitchen fire. Nothing for Gib henceforth but strange, forbidding wilderness, and scavenger’s food, and no shelter, not on the coldest night. The village? But his only two friends, John Frey and Ivy Hill, were being taken from him by the magic of Jael Bettiss and her book…

That book had done this. That book must undo it. There was no time to lose.

The door was not quite latched, and he nosed it open, despite the groans of its hinges. Hurrying in, he sprang up on the table.

It was gloomy in that tree-invested house, even for Gib’s sharp eyes. Therefore, in a trembling fear almost too big for his little body, he spoke a word that Jael Bettiss had spoken, on her first night of power. As had happened then, so it happened now; the dark lamp glowed alight.

Gib pawed at the closed book, and contrived to lift its cover. Pressing it open with one front foot, with the other he painstakingly turned leaves, more leaves, and more yet. Finally he came to the page he wanted.

Not that he could read; and, in any case, the characters were strange in their shapes and combinations. Yet, if one looked long enough and levelly enough—even though one were a cat, and afraid—they made sense, conveyed intelligence.

And so into the mind of Gib, beating down, his fears, there stole a phrase:

Beware of mirrors…

So that was why Jael Bettiss never kept a mirror—not even now, when she could assume such dazzling beauty.

Beware of mirrors, the book said to Gib, for they declare the truth, and truth is fatal to sorcery. Beware, also, of crosses, which defeat all spells…

That was definite inspiration. He moved back from the book, and let it snap shut. Then, pushing with head and paws, he coaxed it to the edge of the table and let it fall. Jumping down after it, he caught a corner of the book in his teeth and dragged it to the door, more like a retriever than a cat. When he got it into the yard, into a place where the earth was soft, he dug furiously until he had made a hole big enough to contain the volume. Then, thrusting it in, he covered it up.

Nor was that all his effort, so far as the book was concerned. He trotted a little way off to where lay some dry, tough twigs under the cypress trees. To the little grave he bore first one, then another of these, and laid them across each other, in the form of an X. He pressed them well into the earth, so that they would be hard to disturb. Perhaps he would keep an eye on that spot henceforth, after he had done the rest of the things in his mind, to see that the cross remained. And, though he acted thus only by chance reasoning, all the demonologists, even the Reverend Montague Summers, would have nodded approval. Is this not the way to foil the black wisdom of the Grand Albert? Did not Prospero thus inter his grimoires, in the fifth act of The Tempest?

Now back to the house once more, and into the kitchen. It was even darker than the parlor, but Gib could make out a basin on a stool by the moldy wall, and smelled an ugly pungency—Jael Bettiss had left her mixture of powdered water after last washing away her burden of false beauty.

Gib’s feline nature rebelled at a wetting; his experience of witchcraft bade him be wary, but he rose on his hind legs and with his forepaws dragged at the basin’s edge. It tipped and toppled. The noisome fluid drenched him. Wheeling, he ran back into the parlor, but paused on the doorstep. He spoke two more words that he remembered from Jael Bettiss. The lamp went out again.

And now he dashed around the house and through the brambles and to the quarry beyond.

It lay amid uninhabited wooded hills, a wide excavation from which had once been quarried all the stones for the village houses and pavements. Now it was full of water, from many thaws and torrents. Almost at its lip was parked John Frey’s touring-car, with the top down, and beside it he lolled, slack-faced and dreamy. At his side, cloak-draped and enigmatically queenly, was Jael Bettiss, her back to the quarry, never more terrible or handsome. John Frey’s eyes were fixed dreamily upon her, and her eyes were fixed commandingly on the figure in the front seat of the car—a slumped, defeated figure, hard to recognize as poor sick Ivy Hill.

“Can you think of no way to end all this pain, Miss Ivy?” the witch was asking. Though she did not stir, nor glance behind her, it was as though she had gestured toward the great quarry-pit, full to unknown depths with black, still water. The sun, at the very point of setting, made angry red lights on the surface of that stagnant pond.

“Go away,” sobbed Ivy Hill, afraid without knowing why. “Please, please!”

“I’m only trying to help,” said Jael Bettiss. “Isn’t that so, John?”

“That’s so, Ivy,” agreed John, like a little boy who is prompted to an unfamiliar recitation. “She’s only trying to help.”

Gib, moving silently as fate, crept to the back of the car. None of the three human beings, so intent upon each other, saw him.

“Get out of the car,” persisted Jael Bettiss. “Get out, and look into the water. You will forget your pain.”

“Yes, yes,” chimed in John Frey, mechanically. “You will forget your pain.”

GIB scrambled stealthily to the running-board, then over the side of the car and into the rear seat. He found what he had hoped to find. Ivy Hill’s purse—and open.

He pushed his nose into it. Tucked into a little side-pocket was a hard, flat rectangle, about the size and shape of a visiting-card. All normal girls carry mirrors in their purses—all mirrors show the truth; Gib clamped the edge with his mouth, and struggled to drag the thing free.

“Miss Ivy,” Jael Bettiss was commanding, “get out of this car, and come and look into the water of the quarry.”

No doubt what would happen if once Ivy Hill should gaze into that shiny black, abyss; but she bowed her head, in agreement or defeat, and began slowly to push aside the catch of the door.

Now or never, thought Gib. He made a little noise in his throat, and sprang up on the side of the car next to Jael Bettiss. His black-stained face and yellow eyes were not a foot from her.

She alone saw him; Ivy Hill was too sick, John Frey too dull. “What are you doing here?” she snarled, like a bigger and fiercer cat than he; but he moved closer still, holding up the oblong in his teeth. Its back was uppermost, covered with imitation leather, and hid the real nature of it. Jael Bettiss was mystified, for once in her relationship with Gib. She took the thing from him, turned it over, and saw a reflection. She screamed.

The other two looked up, horrified through their stupor. The scream that Jael Bettiss uttered was not deep and rich and young; it was the wild, cracked cry of a terrified old woman.

“I don’t look like that!” she choked out, and drew back from the car. “Not old—ugly—”

Gib sprang at her face. With all four claw-bristling feet he seized and dung to her. Again Jael Bettiss screamed, flung up her hands, and tore him away from his hold; but his soggy fur had smeared the powdered water upon her face and head.

Though he fell to earth, Gib twisted in midair and landed uptight. He had one glimpse of his enemy. Jael Bettiss, no mistake—but a Jael Bettiss with hooked beak, rheumy eyes, hideous wry mouth and yellow chisel teeth—Jael Bettiss exposed for what she was, stripped of her lying mask of beauty!

And she drew back a whole staggering step. Rocks were just behind her. Gib saw, and flung himself. Like a flash he clawed his way up her cloak, and with both forepaws ripped at the ugliness he had betrayed. He struck for his home that was forbidden him — Marco Bozzaris never strove harder for Greece, nor Stonewall Jackson for Virginia.

Jael Bettiss screamed yet again, a scream loud and full of horror. Her feet had slipped on the edge of the abyss. She flung out her arms, the cloak flapped from them like frantic wings. She fell, and Gib fell with her, still tearing and fighting.

The waters of the quarry closed over them both.

GIB thought that it was a long way back to the surface, and a longer way to shore. But he got there, and scrambled out with the help of projecting rocks. He shook his drenched body, climbed back into the car and sat upon the rear seat. At least Jael Bettiss would no longer drive him from the home he loved. He’d find food some way, and take it back there each day to eat…

With tongue and paws he began to rearrange his sodden fur.

John Frey, clear-eyed and wide awake, was leaning in and talking to Ivy Hill. As for her, she sat up straight, as though she had never known a moment of sickness.

“But just what did happen?” she was asking.

John Frey shook his head, though all the stupidity was gone from his face and manner. “I don’t quite remember. I seem to have wakened from a dream. But are you all right, darling?”

“Yes, I’m all right.” She gazed toward the quarry, and the black water that had already subsided above what it had swallowed. Her eyes were puzzled, but not frightened. “1 was dreaming, too,” she said. “Let’s not bother about it.”

She lifted her gaze, and cried out with joy. “There’s that old house that daddy owns. Isn’t it interesting?”

John Frey looked, too. “Yes. The old witch has gone away—I seem to have heard she did.”

Ivy Hill was smiling with excitement. “Then I have an inspiration. Let’s get daddy to give it to us. And we’ll paint it over and fix it up, and then—” She broke off, with a cry of delight. “I declare, there’s a cat in the car with me!”

It was the first she had known of Gib’s presence.

John Frey stared at Gib. He seemed to have wakened only the moment before.

“Yes, and isn’t he a thin one? But he’ll be pretty when he gets through cleaning himself. I think I see a white shirt-front.”

Ivy Hill put out a hand and scratched Gib behind the ear. “He’s bringing us good luck, I think. John, let’s take him to live with us when we have the house fixed up and move in.”

“Why not?” asked her lover. He was gazing at Gib. “He looks as if he was getting ready to speak.”

But Gib was not getting ready to speak. The power of speech was gone from him, along with Jael Bettiss and her enchantments. But he understood, in a measure, what was being said about him and the house in the hollow. There would be new life there, joyful and friendly this time. And he would be a part of it, forever, and of his loved home.

He could only purr to show his relief and gratitude.