Orphans in modern literature evolved from orphans of folk and fairytales. There are many orphans in American and British children’s literature, but also in literature from around the world. Some communities have always been set up with strong social networks. Even if parents die, there are no true orphans because the extended family will care for them.

There are no orphans in traditional Hopi society. It would be culturally impossible for a child to fall right through their densely failsafe weave of family, no matter who died. If there was no father or mother, there would be an aunt; if there were no aunts or uncles, there would be a cousin; if there were no cousins, there would still be someone. But even for Hopis, the situation of abandonment seems to be a necessary one to imagine, to hug to oneself in the form of a story. It focuses a self-pity that everyone wants to feel sometimes, and that perhaps helps a child or an adolescent to think through their fundamental separateness. The situation expresses the solitude humans discover as we grow up no matter how well our kinship systems work.

The Child That Books Built

Yet stories of abandonment seem to be a universal, no matter the culture.

WELL-KNOWN LITERARY ORPHANS

American children’s literature has a particularly strong tradition of orphaned — or ‘functionally’ orphaned — child protagonists.

- The Little Match Girl by Hans Christian Andersen does have a father at home, but since she’s in charge of financing her own life, she is functionally an orphan.

- Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm

- Little Lord Fauntleroy

- Tarzan of the Apes

- The Prince and the Pauper

- The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

- Adventures of Huckleberry Finn — It’s commonly said that Jim is a surrogate father who replaces inadequate Pap. Others have said that Huck is having an oedipal crisis, and Jim and Huck are a homoerotic archetype rather than father and son archetype.

- Toby Tyler

- Hans Brinker

- The Secret Garden

- Pollyanna

- Anne of Green Gables

- Max of the Wild Things

- Peter Rabbit

- Tom from Tom’s Midnight Garden

- Stuart Little

- Weetzie Bat

- Harry Potter

- Lyra and Will from Pullman’s Northern Lights

- Dorothy who went on a mythical journey to see The Wizard Of Oz lived with her aunt and uncle in Kansas

- Kira of Gathering Blue

- Mowgli of Kipling’s Jungle Book

- Jim Hawkins of Treasure Island

- The children of Swallows and Amazons

- Brian from Hatchet

- Jerry Renault from The Chocolate War

- In modern middle grade fiction, Crow in Lauren Wolk’s Beyond The Bright Sea wants to find out who she really is, especially in relation to where she comes from. The ideology behind such stories is that you can’t possibly find out where you’re going until you find out where you’ve come from. But in the end she realises that her real family is her found family.

- Bye Bye Baby is a fairly rare example of an orphaned picture book character — perhaps quite disturbing for actual toddlers, but funny for adult co-readers who are (over-) familiar with the orphaned child sob story. This picture book ends as a found-family narrative.

ORPHANS AND REALISM

Stories in the 1960s and 1970s of the stories children themselves tell at two and three found a relationship between how ‘socially acceptable’ the actions in them were, and how much they took place in the recognisable everyday world of the child’s own experience. If they included taboo behaviour like hitting a parent or wetting yourself, or major reversals of emotional security, like having a parent die or being abandoned by parents, they were less likely to have a realistic setting (69 percent versus 94 per cent), less likely to feature the teller as a character (13 per cent versus 39 per cent), and much less likely to be told in the present tense (19 per cent versus 56 per cent.) Dangerous things were moved further away in place and in time, and were not allowed to happen even to a proxy with the same name as the child. Children a year or two older no longer varied the present tense and past tense, because they consistently told all stories in the past tense; but they used settings in the same way, moving the troubling material outward into fantasy, into the zones where a story event reflected a real event less directly… To castles pirate ships, space; to the forest. There, the terrible things you might do, and the terrible things that might happen to you — not always easy to separate — can be explored without them jostling the images you most want to guard, the precious representations of your essential security.

The Child That Books Built, Frances Spufford

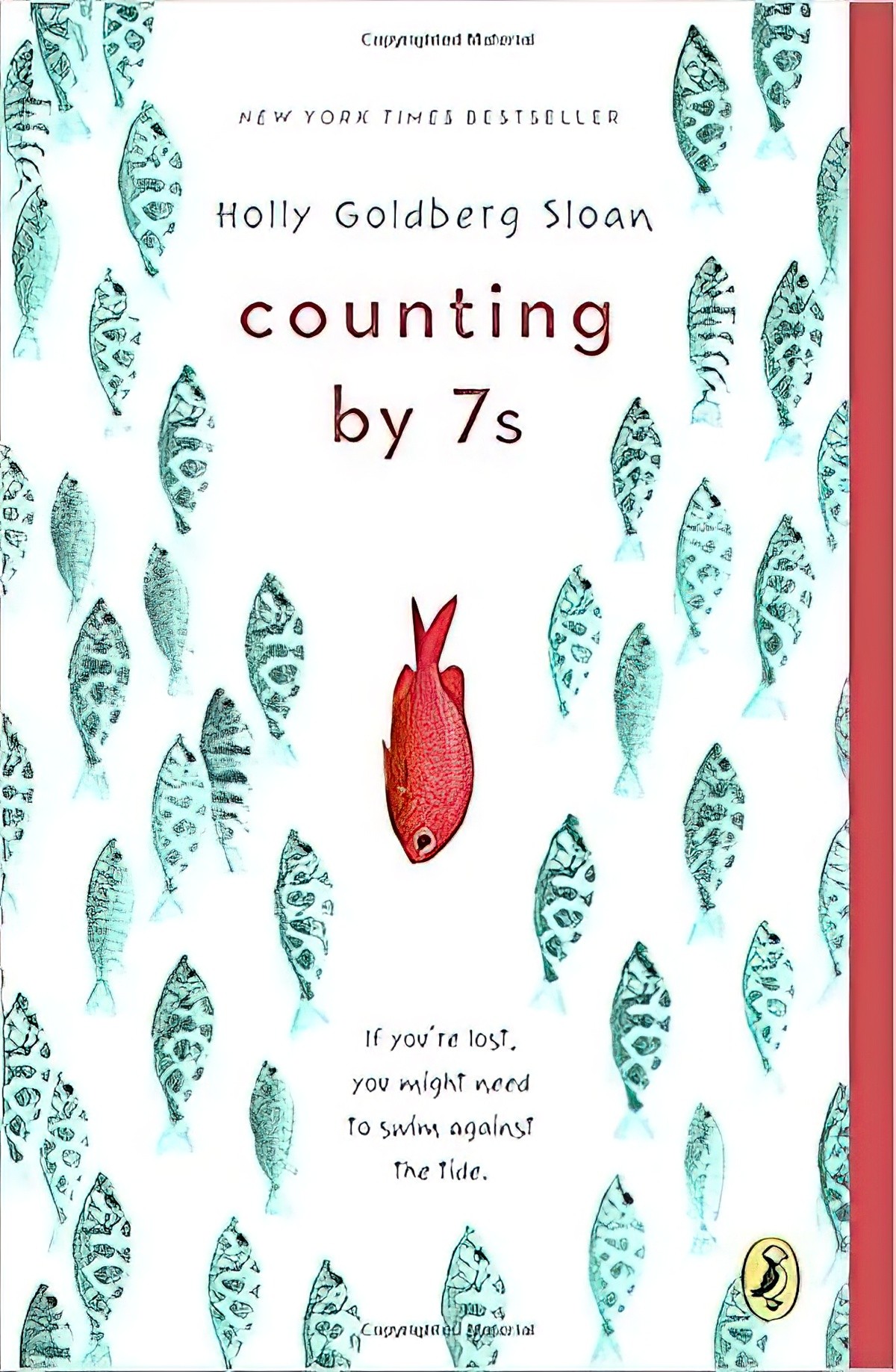

Willow Chance is a twelve-year-old genius, obsessed with nature and diagnosing medical conditions, who finds it comforting to count by 7s. It has never been easy for her to connect with anyone other than her adoptive parents, but that hasn’t kept her from leading a quietly happy life…until now.

Suddenly Willow’s world is tragically changed when her parents both die in a car crash, leaving her alone in a baffling world. The triumph of this book is that it is not a tragedy. This extraordinarily odd, but extraordinarily endearing, girl manages to push through her grief. Her journey to find a fascinatingly diverse and fully believable surrogate family is a joy and a revelation to read.

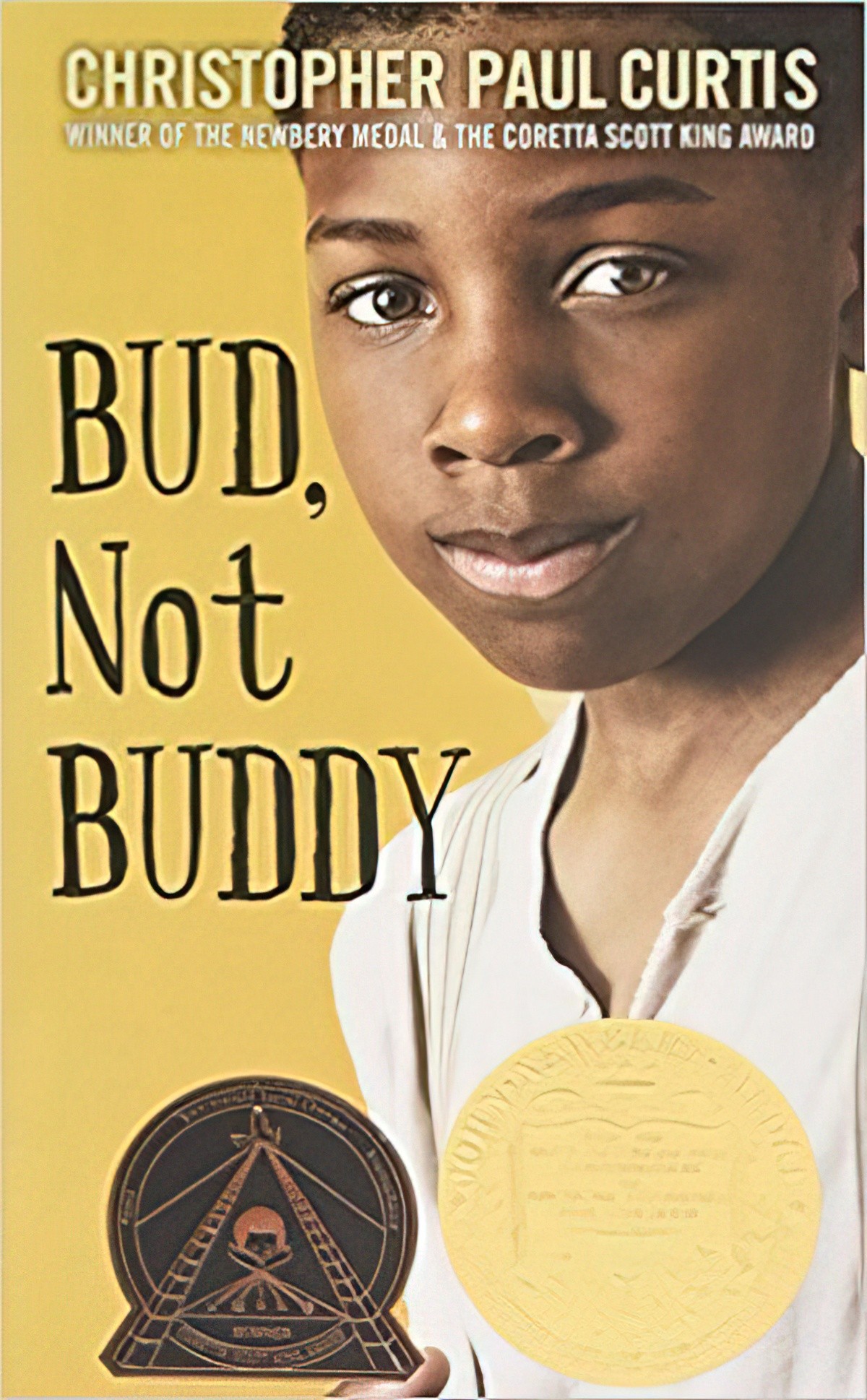

It’s 1936, in Flint, Michigan. Times may be hard, and ten-year-old Bud may be a motherless boy on the run, but Bud’s got a few things going for him:

He has his own suitcase full of special things.

He’s the author of Bud Caldwell’s Rules and Things for Having a Funner Life and Making a Better Liar Out of Yourself.

His momma never told him who his father was, but she left a clue: flyers advertising Herman E. Calloway and his famous band, the Dusky Devastators of the Depression!!!!!!

Bud’s got an idea that those flyers will lead him to his father. Once he decides to hit the road and find this mystery man, nothing can stop him–not hunger, not fear, not vampires, not even Herman E. Calloway himself.

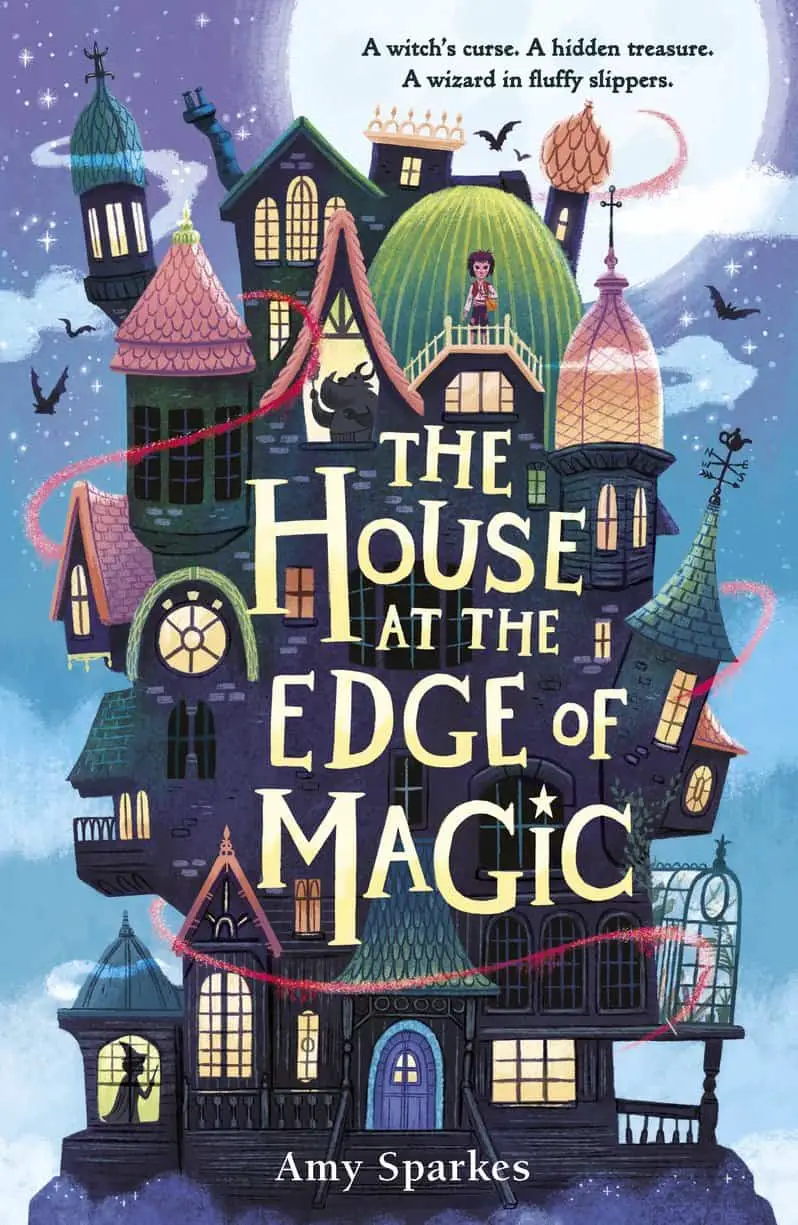

Nine is an orphan pickpocket determined to escape her life in the Nest of a Thousand Treasures. When she steals a house-shaped ornament from a mysterious woman’s purse, she knocks on its tiny door and watches it grow into a huge, higgledy-piggeldy house. Inside she finds a host of magical and brilliantly funny characters, including Flabberghast – a young wizard who’s particularly competitive at hopscotch – and a hideous troll housekeeper who’s emotionally attached to his feather duster. They have been placed under an extraordinary spell, which they are desperate for Nine to break. If she can, maybe they can offer her a new life in return…

WHAT ACCOUNTS FOR ALL THESE ORPHANS?

This is almost too obvious to mention, but in earlier times there were, literally, a lot more orphans. People died younger. Women frequently died in childbirth.

So, why do so many mothers die in fairytales and other stories? I could be wrong, but I have pondered it, and had even before I was asked the question.

If stories are told and re-told because they contain survival information, as I and others have argued, then why so many stories with deceased moms?

Because, I think, for most of human history this was not an uncommon occurrence. Mothers did die, often in childbirth. But children need to know that life goes on and that they can survive even this ordeal. In Bruno Bettelheim’s* book on the subject of fairytales, The Uses of Enchantment, he points out that often there is fairy godmother or some such figure that is a kind of ghost of the mother looking after her child even after death.

Why Don’t People Ask Why?

*Bettelheim was an asshole who probably set psychology back a couple of decades. Look up his theories on the causes of autism. (tl;dr: Refrigerator Mothers)

Less obvious to modern readers are social customs which meant children were quite frequently without their mothers even if the mothers hadn’t died. When women and children are treated as chattels, the importance of the woman, even as mother, is not necessarily honoured. A woman’s place was especially tenuous before the custom of the eldest son inheriting everything. (Problematic as that was in its own right.)

The chronicles of the Anglo-Saxon and Merovingian dynasties, before the establishment of primogeniture, are bespattered with the blood of possible herbs, done away with by consorts ambitious for their own progeny — the true wicked stepmothers of history, who become embedded in stories as eternal truths. Moreover, children whose fathers had died often stayed in the paternal house, to be raised by their grandparents or uncles and their wives. Their mothers were made to return to their natal homes, and to forge another, advantageous alliance for their own parents’ future. Widows remarried less frequently than widowers.

From The Beast to the Blonde by Marina Warner

In other words, children belonged to the household (their father), and the women were required as vessels, but after that, frequently disposed of.

Apart from the culture of primogeniture, there was also:

- general patrilineage (in which children belong to the father)

- dotal obligations (ie. the customs around dowries, in which the woman’s family is required to give resources to the man’s family in exchange for ostensibly looking after here. There are many knock-on effects from these customs, which is why it has been banned in countries such as India.)

- female exogamy (in which women are required to marry outside their own social group, often moving far away with no more support from her natal family or childhood friends. In this case, if the marriage breaks up, the woman is sent far from her children.)

- polygamy (in which fathers had more than one wife, each competing for scarce resources, and in which sister wives shared the childcare, inheriting children if one of them dies)

ORPHANS IN CONTEMPORARY STORIES

Why is there still a disproportionate number of kids without parents, even in contemporary literature?

First, an unexpected answer. Alison Lurie has noticed that authors of classic children’s literature may have been disproportionately orphaned themselves:

The classic makers of children’s literature are not usually men and women who had consistently happy childhoods — or consistently unhappy ones. Rather they are those whose early happiness ended suddenly and often disastrously. Characteristically, they lost one or both parents early. They were abruptly shunted from one home to another, like Louisa May Alcott, Kenneth Grahame, and Mark Twain — or even, like Frances Hodgson Burnett, E. Nesbit, and J.R.R. Tolkien, from one continent to another. L. Frank Baum and Lewis Carroll were sent away to harsh and bullying schools; Rudyard Kipling was taken from India to England by his affectionate but ill-advised parents and left in the care of stupid and brutal strangers. Cheated of their full share of childhood, these men and women later re-created, and transfigured, their lost worlds. Though she was primarily an artist rather than a writer, Kate Greenaway belongs in this category.

Alison Lurie: Don’t Tell The Grown-ups: The power of subversive children’s literature

In Audacious Kids, Jerry Griswold puts the large numbers of orphans in children’s literature down (partly) to intertextuality — in other words, authors were borrowing from each other, and this led to a whole bunch of orphans.

Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer (1876), for example, clearly inspired the story of Rebecca Sawyer when Kate Douglas Wiggin decided to write about a tomboy in Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1903). In the same way, the subplot of Laurie and his grandfather in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1868) seems to me to have been enlarged and become the story of Cedric and his grandfather in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Little Lord Fauntleroy (1885) — a novel that served, in turn, as the basis for Eleanor Porter’s Pollyanna (1913).

But perhaps this is the most important reason for the prevalence of orphans throughout children’s literature: It gets adults out of the way, allows for psychological growth and ‘an equally exciting and disturbing idea’:

The prevalence of orphans in children’s fiction seems to relate to a central concern adults have with children’s independence and security. Orphans are of necessity independent, free to have adventures without the constraints of protective adults. At the same time, they automatically are faced with the danger and discomfort of lack of parental love. Childhood is usually understood as that time of life when one needs parental love and control. As a result, it seems, adults tend to believe that the possibility of being orphaned—of having the independence one wants and yet having to do without the love one needs—is an exciting and disturbing idea for children who are not in fact orphans, and a matter of immediate interest for those who are. In depicting orphans, writers can focus on children’s desire for independence, or on their fear of loss of security. In some cases, they offer interesting combinations of the two, as in Wolff’s Make Lemonade: one young girl teachers another independence by offering comfort and security. In doing so, she herself must learn, first, to compromise her own desire for independence and then, eventually, to give up the comfort of the relationship and become independent again.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature by Reimer and Nodelman

(There are other ways of getting adults out of the way of child heroes in children’s stories. It’s not entirely necessary to kill the mother off.)

THE SURPRISING COMFORT OF DEAD MOTHERS

Far fewer modern children have lost their mothers, though many are estranged from a parent or a grandparent. Still others fear losing their mother. Marina Warner makes the case that a dead mother in a story is, paradoxically, a comfort to a child:

[Dead mother fantasy] can also comfort bereaved children, who, however irrationally, feel themselves abandoned by their dead mothers, and even guilty for their disappearance. One English Cinderella story, called ‘Tattercoats’, perceptively focusses on this type of grief: the king figure mistreats his granddaughter ‘because at her birth, his favourite daughter died’. In this case, her ragged, starving, neglected state reflects his excess of mourning and her anguished guilt, and neither of them can be healed of the wound — the story has an unhappy ending.

FromThe Beast to the Blonde by Marina Warner

Warner also points out how the Grimms had a huge influence on storytelling for children, and they had their own reasons for getting rid of mothers:

Paradoxically, the best possible intentions can also contribute to the absence of mothers from the tales. In the case of ‘Schneewittchen’ (Snow White), for instance, the Grimm altered the earlier versions they had taken down in which Snow White’s own mother suffered murderous jealousy of her and persecuted her. The 1819 edition is the first to introduce a stepmother in her place; the manuscript and the editions of 1810 and 1812 place Snow White’s natural mother at the pivot of the violent plot. But it was altered so that a mother should not be seen to torment a daughter. […]

Wilhelm [Grimm] in particular [infused] the new editions [of the Grimm fairy tales] with his Christian fervour, emboldening the moral strokes of the plot, meting out penalties to the wicked and rewards to the just, to conform with prevailing Christian and social values. They also softened the harshness — especially in family dramas. They could not make it disappear altogether, but in ‘Hansel and Gretel’, for example, they added the father’s miserable reluctance to an earlier version in which both parents had proposed the abandonment of their children, and turned the mother into wicked stepmother. On the whole, they tended towards sparing the father’s villainy, and substituting another wife for the natural mother, who had figured as the villain in the versions they had been told: they felt obliged to deal less harshly with mothers than the female storytellers whose material they were setting down.

The disappearance here of the original mothers forms a response to the harshness of the material: in their romantic idealism, the Grimms literally could not bear a maternal presence to be equivocal, or dangerous, and preferred to banish her altogether.r Fro them, the bad mother had to disappear in order for the ideal to survive and allow Mother to flourish as symbol of the eternal feminine, the motherland, and the family itself as the highest social desideratum.

From The Beast to the Blonde by Marina Warner

THE ORPHAN UR-STORY STRUCTURE

Writing about American children’s literature, Griswold explains what turns up again and again in the ‘basic plot’, or the ‘ur-story’ of the orphaned child:

- A child is born to parents who married despite the objections of others.

- For a time, the family is well-to-do, members of the nobility or otherwise happy and prosperous.

- Then the child’s parents die/The child is separated from its parents and effectively orphaned.

- Without their protection, the child suffers from poverty and neglect and (if nobly born) dispossessed.

- The hero/ine makes a journey to another place and is adopted into a second family.

- In these new circumstances the child is treated harshly by an adult guardian of the same sex but sometimes has help from an adult of the opposite sex.

- Eventually, however, the child triumphs over its antagonist and is acknowledged.

- Finally, some accommodation is reached between the two discordant phases of the child’s past: life in the original or biological family and life in the second or adoptive family.

Maria Nikolajeva has also outlined these points and attributes the pattern to the fairytale family of Cinderella.

Maria Nikolajeva also makes a distinction between sad death and emotionless death when writing about the orphans in The Secret Garden. Death of the parents is sometimes just a plot device rather than something that leads to psychological growth:

A great number of fairy tales begin with the death of one or both parents, which sets in motion all the further events and complications of the plot. […] Just as we do not feel sorry for the death of the fairy-tale hero’s parents, because it is an indispensable part of the plot, we do not feel sorry for the death of Mary [Lennox’s] parents or Colin’s mother (especially since we do not feel much empathy with either of the children on the whole). Neither do the children grieve their dead, for different reasons. Colin has never met his mother, and the servants are forbidden to speak of her (ritual taboo!). […] while death certainly has a ritual function in the novel, it is not the kind of death that brings about the characters’ insight about their own mortality. On the contrary, the most important part of Colin’s development implies the change from his firm belief that he will soon die to an equally firm belief that he will not die at all, from “No one believes I shall live to grow up to “I shall live forever and ever and ever!”

Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature

Marina Warner makes the same point but uses Beauty and the Beast as an example:

The absence of the mother from the tale is often declared at the start, without explanation, as if none were required; Beauty appears before us, in the opening paragraph of the earliest written version of ‘Beauty and the Beast’ with that title, in 1740, as a daughter to her father, a sister to her six elders, a biblical seventh child, the cadette, the favourite: nothing is spoken about her father’s wife. Later, it will turn out that Beauty is a foundling, and was left by the fairies, after her fairy mother was disgraced by union with a mortal — not the father Beauty knows, but another, higher in rank, more powerful.

From The Beast To The Blonde by Marina Warner

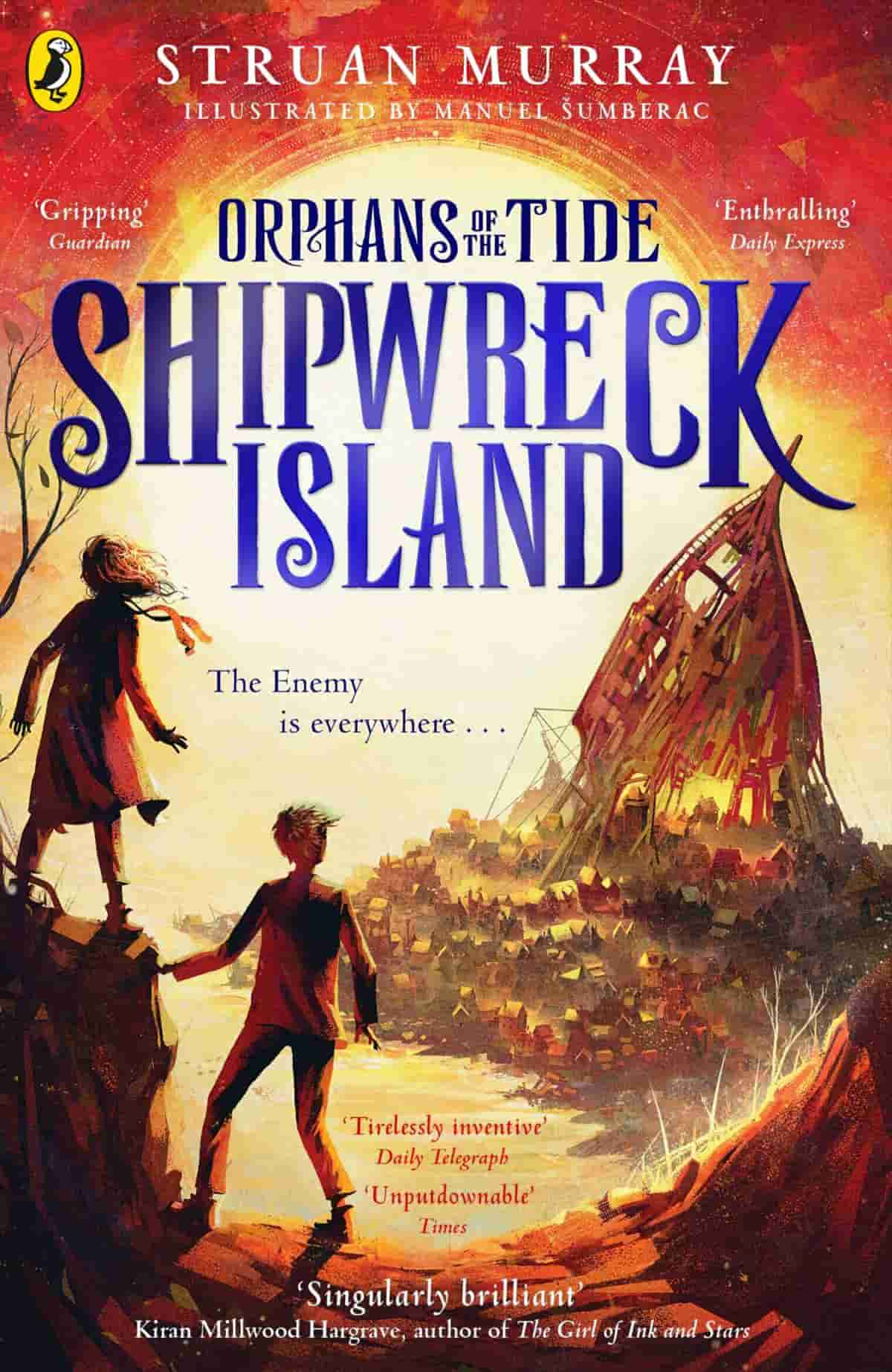

The City was built on a sharp mountain that jutted improbably from the sea, and the sea kept trying to claim it back. That grey morning, once the tide had retreated, a whale was found on a rooftop.

When a mysterious boy washes in with the tide, the citizens believe he’s the Enemy – the god who drowned the world – come again to cause untold chaos.

Only Ellie, a fearless young inventor living in a workshop crammed with curiosities, believes he’s innocent.

But the Enemy can take possession of any human body and the ruthless Inquisition are determined to destroy it forever.

To save the boy, Ellie must prove who he really is – even if that means revealing her own dangerous secret . . .

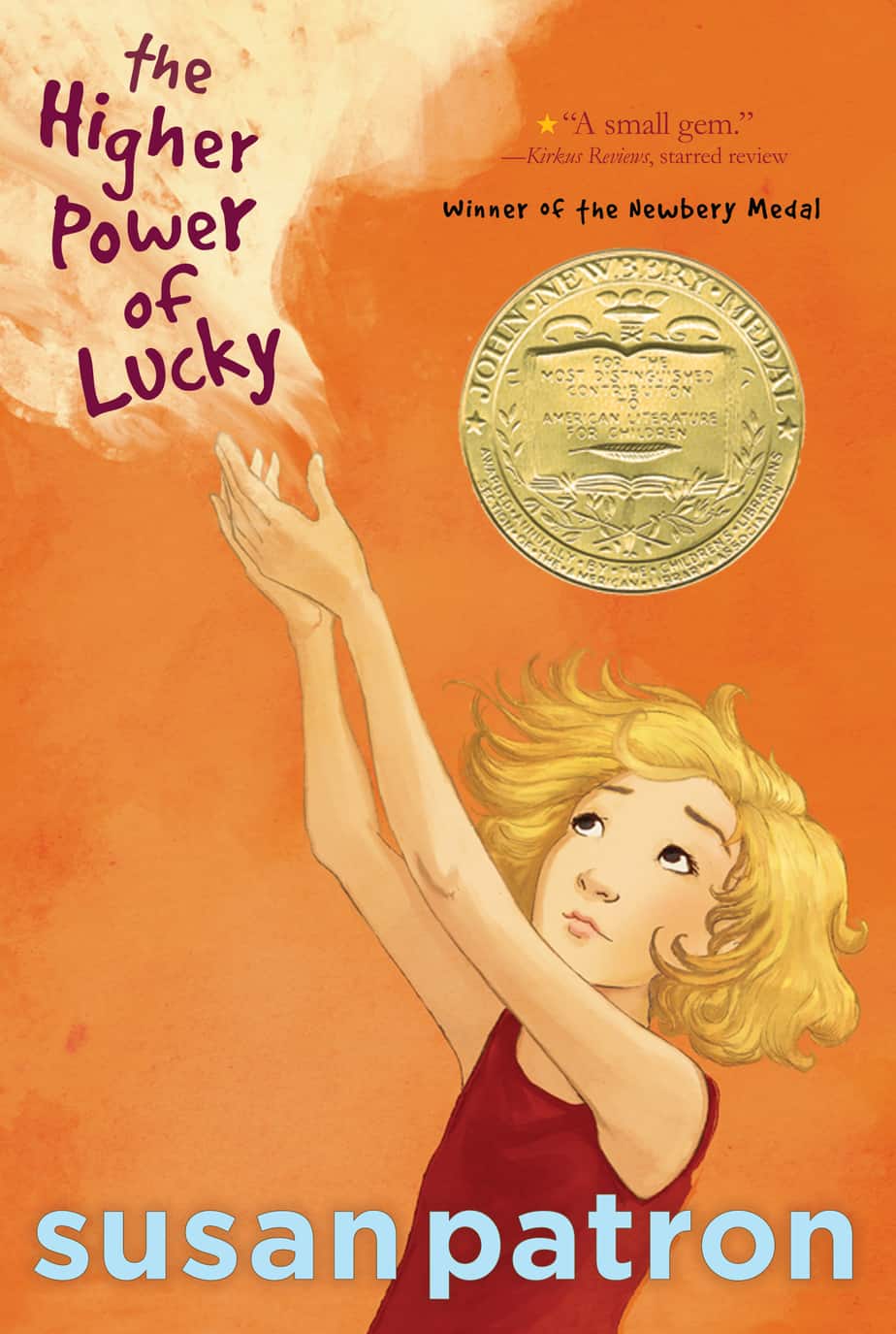

Believing that her French guardian is about to abandon her to an orphanage in the city, ten-year-old Lucky runs away from her small town with her beloved dog by her side in order to trek across the Mojave Desert in this Newbery Medal–winning novel from Susan Patron.

Lucky, age ten, can’t wait another day. The meanness gland in her heart and the crevices full of questions in her brain make running away from Hard Pan, California (population 43), the rock-bottom only choice she has.

It’s all Brigitte’s fault — for wanting to go back to France. Guardians are supposed to stay put and look after girls in their care! Instead Lucky is sure that she’ll be abandoned to some orphanage in Los Angeles where her beloved dog, HMS Beagle, won’t be allowed. She’ll have to lose her friends Miles, who lives on cookies, and Lincoln, future U.S. president (maybe) and member of the International Guild of Knot Tyers. Just as bad, she’ll have to give up eavesdropping on twelve-step anonymous programs where the interesting talk is all about Higher Powers. Lucky needs her own — and quick.

But she hadn’t planned on a dust storm.

Or needing to lug the world’s heaviest survival-kit backpack into the desert.

The Higher Power Of Lucky by Susan Patron is a good crossover novel. There’s a musicality in the writing and the most endearing of characters.

There was controversy around this book and it has been banned by certain libraries. The reason becomes apparent after reading the first two paragraphs which is about something overheard at an alcoholics anonymous meeting and includes the word ‘scrotum’, which is what got it banned.

We are thus planted firmly in the world of reality. This is a book peopled with true-to-life characters. Yet the writer brilliantly channels her idea and possibly her memory of a nine-year-old’s worldview. The author has achieved a highwire act in balancing the informed worldview of an adult writer but making it seem totally through the eyes of a nine-year-old.

The premise of the story is that Lucky has misunderstood something her foster/stepmother has said and thinks she’s going to be abandoned.

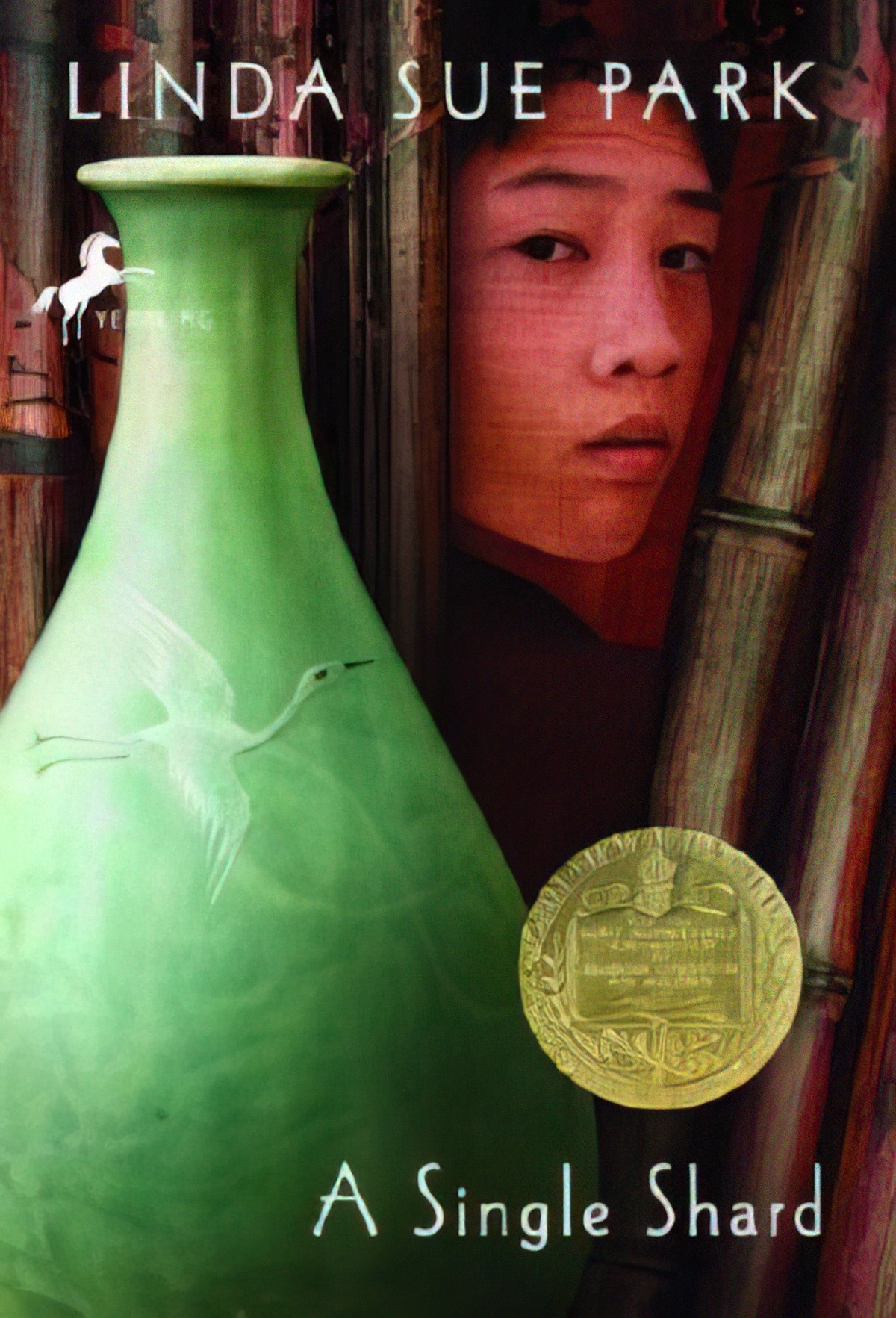

Tree-ear, an orphan, lives under a bridge in Ch’ulp’o, a potters’ village famed for delicate celadon ware. He has become fascinated with the potter’s craft; he wants nothing more than to watch master potter Min at work, and he dreams of making a pot of his own someday. When Min takes Tree-ear on as his helper, Tree-ear is elated–until he finds obstacles in his path: the backbreaking labor of digging and hauling clay, Min’s irascible temper, and his own ignorance. But Tree-ear is determined to prove himself–even if it means taking a long, solitary journey on foot to present Min’s work in the hope of a royal commission . . . even if it means arriving at the royal court with nothing to show but a single celadon shard.

TRADITIONAL VS MODERN ORPHANED CHARACTERS IN KIDS’ BOOKS

Traditional orphan stories often borrow the linear ‘Cinderella structure’ in which the hero loses his/her home, becomes a nobody, suffers trials and is helped out of a bad situation at just the right moment by a ‘helper’ archetype. In these stories, the true specialness of the hero is finally made apparent to everyone in the setting, and they live happily ever after.

A modern orphan story tends to dispense with so many of those Cinderella story beats. An example is The Great Gilly Hopkins, which has an open ending by contrast. For modern orphans, there is not necessarily a ‘happy ever after’.

There are some basic guidelines to crafting modern stories for children: One is that you must not be overtly didactic; another is that you must have the children solve any problems for themselves. That means, in short, that the teachers and parents need to stay right out of it. This is the kidlit version of deus ex machina, in which ‘god’ descends from the sky to resolve the problem for the hero. Let’s call it ‘parentis ex machina’.

What sort of setting is often used for keeping adults at bay?

1. Boarding schools: Harry Potter, Mallory Towers etc

2. Fantasy portals into adult-free realms: Narnia etc

3. Tragic real-world circumstances, in which parents have died or been posted abroad etc.

FUNCTIONAL ORPHANS

Modern children’s stories are full of compromised parents (most often busy, sometimes stupid, sometimes neglectful or drug addled) and so modern child characters are ‘functional’ orphans:

We live in a culture that refers constantly to helicopter parents, yet there are many young adult books with self-absorbed, negligent parents who can’t be bothered to attend to their children’s needs. In children’s literature you need a certain degree of parental incompetence and absence to enable the child’s “triumphant rise.” An earlier age depicted cruel, abusive parents or simply killed off the biological mother and father, but in a very different genre–fairy tales and fantasy. Is the parent problem in YA fiction symptomatic of a new hands-off attitude among parents today?

Maria Tatar

A good example of a functional orphan is The Little Match Girl, whose mother appears to be dead, but who technically has a father at home. But because she is out in the world earning a ‘living’, he’s hardly a parental figure — more of an absent threat.

The child who angrily wishes his mother to drop dead for not having gratified his needs will be traumatized greatly by the actual death of his mother — even if this event is not linked closely in time with his destructive wishes. He will always take part or the whole blame for the loss of his mother. He will always say to himself — rarely to others — “I did it, I am responsible, I was bad, therefore Mommy left me.” It is well to remember that the child will react in the same manner if he loses a parent by divorce, separation, or desertion. Death is often seen by a child as an impermanent thing and has therefore little distinction from a divorce in which he may have an opportunity to see a parent again.

On Death and Dying by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

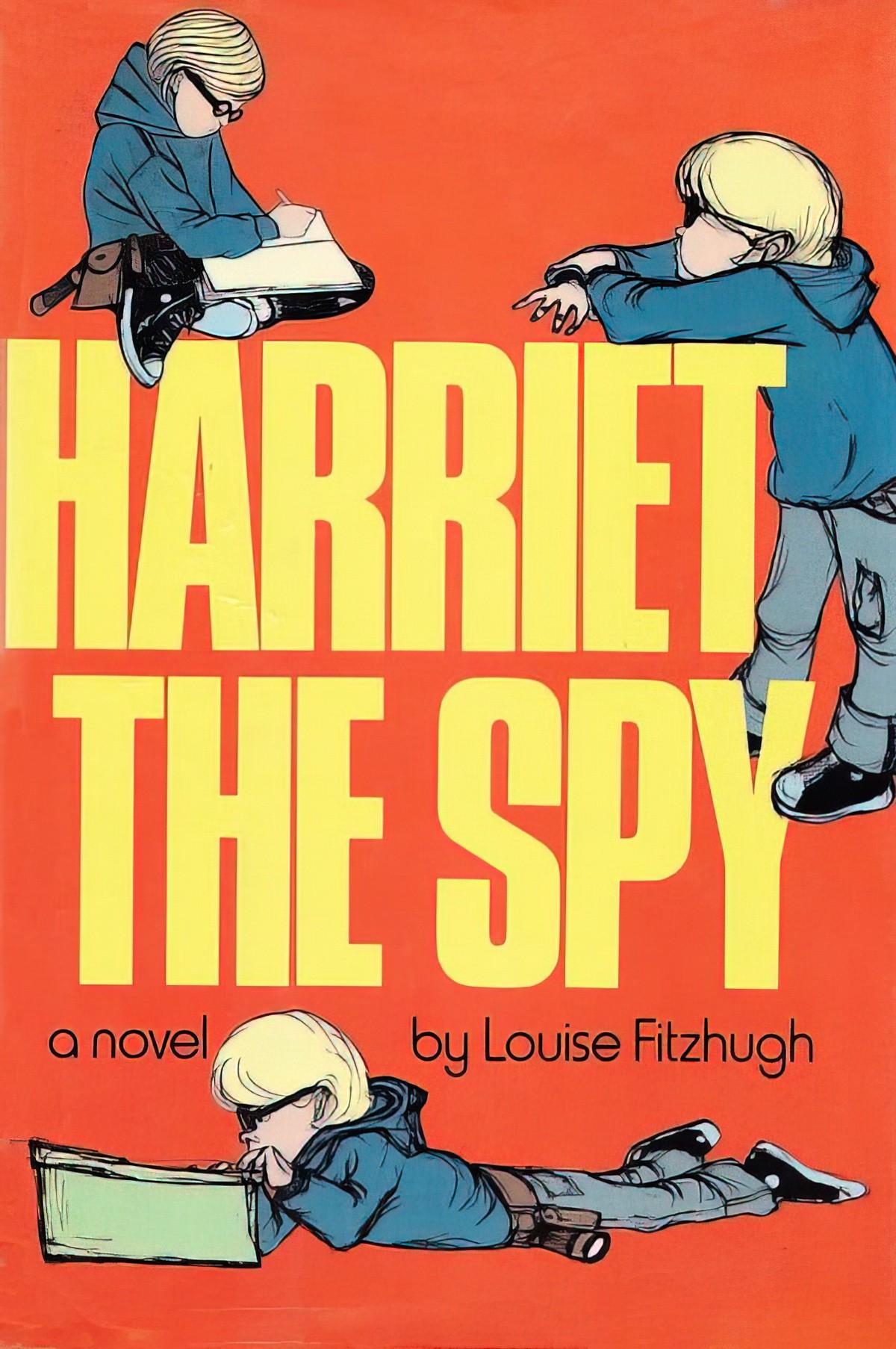

Harriet The Spy is another good example of a functional orphan.

One pleasant result of the disappearance of old assumptions about the infallibility of parents and the duty of children to toe the line has been the arrival of a number of highly-individual child characters — usually girls — whose personalities have been allowed by their authors to develop without too much regard for what constitutes a proper example. Harriet, in Harriet the Spy (1964) by Louise Fizhugh (1928-74), lives in Manhattan, is eleven, and intends to be Harriet M. Welsch the famous writer when she grows up.

John Rowe Townsend, Written For Children

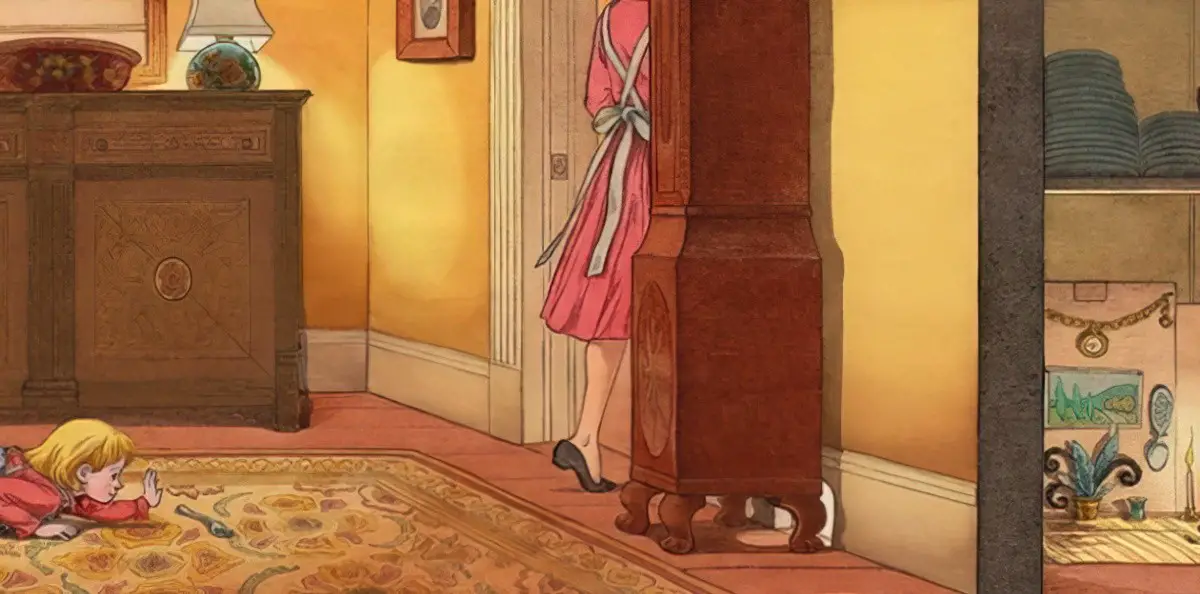

From The Mixed-up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler

…another heroine who is her own child and nobody else’s. Claudia has decided, coolly, to run away from home, returning only when everyone has learned a lesson in Claudia-appreciation. Since she believes in beauty, education, and comfort, and lives within commuting distance of New York City, where better to run away to than the Metropolitan Museum of Art?

John Rowe Townsend, Written For Children

HEADLESS WOMEN

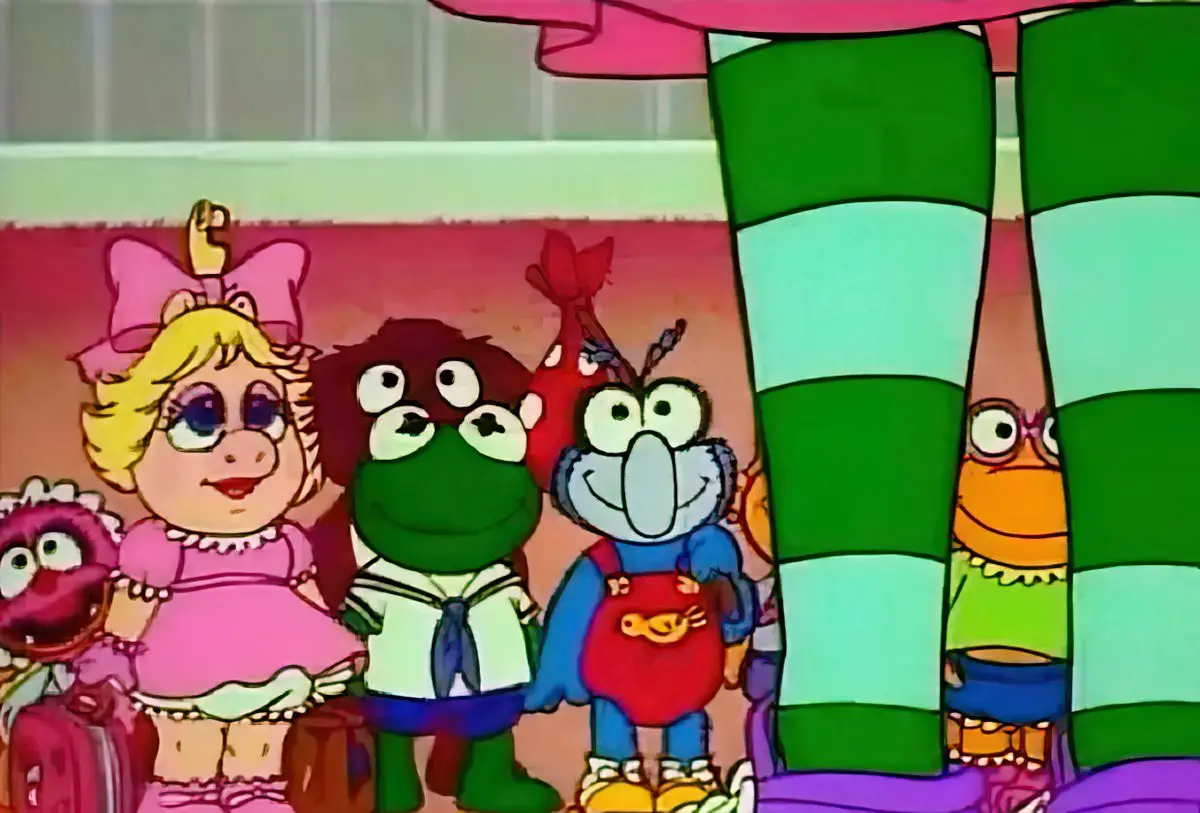

In picture books, the artist can help ‘orphan’ the child character but also offer the reassuring presence of parents by cutting off the parent’s head.

This was a trick used in the cartoon series Muppet Babies (1984—), in which we never see the nanny’s head — only her green and white striped stockings. “The caregiver is here but not important to the story.” That’s the clear message.

Naturally, this lead to a meme in which we imagine Nanny has no actual head.

IMAGINARY PARENTS

Despite all these dead parents, Roberta Seelinger Trites noticed something about orphans in young adult literature in particular: ‘the propensity of adolescents with neither actual nor effective surrogate parents to create imaginary parents against whom to rebel.’ This is apparently a Lacanian principle, for those familiar with that (not me). Trites offers the following examples of YA characters who create imaginary parents and then rebel against them:

- Judy Abbott, the main character of Daddy-Long Legs

- Junior Brown, The Planet of Junior Brown

- Gilly in The Great Gilly Hopkins, in which the mental construction of her mother is nothing like the reality

- Ellen Conford, of To All my Fans, with Love, from Sylvie

Trites coined her own term to describe these parents who are parents in name only: in logo parentis. (In loco parentis, logos.)

PARENTS IN YOUNG ADULT LITERATURE

There has been a conversation lately about something like ‘symbolic annihilation’ of parents in young adult literature.

I legit don’t understand the parents in YA convo. Why does it matter if your book has parents or not? Make it a good book. I hope I’m not alone in this. It just feels like every other month we’re debating why books need more parents or saying that parents have no place in YA

@whimsicallyours

Set in the late Middle Ages, a quick-witted orphan, abused by his grandfather, risks his life to care for a wounded knight who is on a quest but can’t remember what he is searching for. Exciting, engrossing, enchanting!

Reading Level: Ages 11-13.

Widge is an orphan with a rare talent for shorthand. His fearsome master has just one demand: steal Shakespeare’s play “Hamlet”–or else. Widge has no choice but to follow orders, so he works his way into the heart of the Globe Theatre, where Shakespeare’s players perform. As full of twists and turns as a London alleyway, this entertaining novel is rich in period details, colorful characters, villainy, and drama.”A fast-moving historical novel that introduces an important era with casual familiarity.” —School Library Journal, starred review (1998)

RELATED

List of Orphan related tropes from TV Tropes

Best Books About Orphans, a Goodreads list, in which you’ll see that the list is heavily populated with children’s literature

In this moving talk, British playwright and poet Lemn Sissay opens up about his experience of being a fostered child and child in care in the 1960s and 70s in the UK. This talk is of interest for kid-lit fans not just because Sissay has written for children (“The Emperor’s Watchmaker”), but also because he references lots of cared-for, fostered and orphaned children in children’s literature at the start of his talk.

Playing By The Book

An “elder orphan” is someone who is aging alone, without parents, a spouse, siblings, children, or grandchildren. Its population is growing—and America is terribly unprepared.

Judy Colbert

Header painting: Thomas Benjamin Kennington – Orphans