In the short story “Who’s-Dead McCarthy“, Irish short story writer Kevin Barry takes someone’s darkly morbid fascination with death and exaggerates it in a story-length character sketch — a man who talks about death so incessantly that people cross the road to avoid him. It’s wonderful.

I think humour only ever exists in something that sets out to be serious. Anything that sets out to be humorous is doomed.

Common Faults In Short Stories

Do you know anyone who takes a keen interest in death? My mother is a longterm resident of the area where I grew up. She’s worked in various fields and knows a hell of a lot of people. She’s also very good at remembering names and faces. So every morning, first thing she does when reading the paper is open to the funerals page at the back. Every now and then — more and more often more lately — she will say, “Oh no, Such-and-such has died.” Sometimes this is whispered in a mournful tone — sometimes stated matter-of-fact.

As a teenager living at home, I found this aspect of my mother’s morning routine comically morbid. I couldn’t imagine ever taking such an interest in the death pages myself.

Read the full text of “Who’s-Dead McCarthy” at The Irish Times.

STORYWORLD OF “WHO’S-DEAD MCCARTHY”

My second cousin, who is a Northern Irish New Zealander, swore he saw the Grim Reaper jumping over the back fence the evening before his father died. With this as the sum total of evidence, I have a feeling that the story of the Grim Reaper is quite popular in Ireland.

[McCarthy’s] role as our messenger of death along the length of O’Connell Street and back seemed to be of a tradition. Such a figure has perhaps always walked the long plain mile of the street and spoken the necessary words, a grim but vital player in the life of a small city.

Ireland is a Western culture of course, and compared to various non-Western cultures the West is reticent about death, preferring to deal with it mainly via metaphor, folklore and symbolism.

This story is a case in point, and opens with a description of Limerick in winter. Winter is the perfect symbolic season for a story entirely about death. There’s no summery ironic juxtaposition here.

Con McCarthy himself is depicted as a part of the landscape, setting him up as a supernatural figure, at one with nature (nature including death):

The main drag was the daily parade for his morbidity. Limerick, in the bone evil of its winter, and here came Con McCarthy, haunted-looking, in his enormous, suffering overcoat. The way he sidled in, with the long, pale face, and the hot, emotional eyes.

The city of Limerick contains the River Shannon, which plays on an age-old fear of rivers as places of death. They literally were, before modern plumbing. When I traced my own family history I discovered an ancestor had been killed while crossing a river on horseback. You’d probably find the same. The death records in England show that in the early modern period, drownings were quite common with toddlers — they could drown in ditches, in brooks, or in tubs of wort, the liquid extracted from the mashing process during the brewing of beer or whisky. Girls were more likely to die falling into buckets and wells than rivers because they stayed closer to home. Anyway, it’s no surprise that we historically fear water.

The symbolic river running through Limerick in “Who’s-Dead McCarthy” is a proxy for The River Styx in Greek mythology — the body of water which supposedly takes us from the world of the living to whatever lies beyond.

NARRATIVE VOICE OF “WHO’S DEAD MCCARTHY”

I was once in a writing group with an Irish fellow and felt a little envious of his distinctive, comedic voice. He had a way of writing which felt like he only had to transcribe his natural speaking voice onto the page and whatever he said would come out funny.

Of course, that was a vast under-appreciation of what it takes to write funny stories in a strong, distinctive voice. I was forgetting that I, too, come from a country where my regional accent is naturally comedic to outsiders. Flight of the Conchords is testament to this phenomenon, in which Brett and Jemaine ham up the Kiwi for laughs.

This is why I’m somewhat sympathetic to the commenter who had this to say about Kevin Barry’s story at the Irish Times:

How much of this is selling stock country types to city audiences? Also the romantic fallacy that there is wisdom in the primitive and misses the point that our man Con is really a groupie since what he is obsessed with is the star move everyone in the country can make — dying is the one thing that will get you in the paper and on radio, make you star of the show in the big house with the cross on it, in the same-sized box, with the same priest saying the same mass, going to the same limo in the sky where you’ll be the same as everyone else. It’s the small — or dull-man’s — revenge.

The great danger in writing with non-dominant dialects for laughs is that some readers will feel you’re lampooning the underdogs. And that is never a nice feeling. Those who speak with naturally ‘funny’ accents are at an advantage when aiming for comedy, but the flip side is, we also have trouble being taken seriously. Though I am not Irish, I understand this quandary first hand due to living outside New Zealand while speaking (for a while, at least) with a hilarious Kiwi accent.

STORY STRUCTURE OF WHO’S-DEAD MCCARTHY

“Who’s-Dead McCarthy” begins as a comical character sketch of one character (Con McCarthy), as told through the eyes of the ‘straight man’ narrator. We know nothing of this narrator except that he is ‘normal’ whereas Con McCarthy is not normal — unduly obsessed with death.

But then the story shifts — gradually rather than suddenly — and the story is now about the narrator’s response to death. The story morphs into an introspective, reflective meditation about the narrator, and about all of us, and how Con McCarthy has been instrumental in the narrator’s own perspectival shift.

So who is the ‘main’ character of such a story? They both are, equally, but for purposes of analysis, the ‘main character’ is the one who changes the most over the course of the narrative. So in this case it is the narrator. (Don’t fall into the trap of thinking that ‘change in circumstance’ equals ‘change in perspective’. If we were going for ‘change in circumstance’ then Con would win out, since he goes from living to dead.)

SHORTCOMING

The audience is fully encouraged to enjoy Con McCarthy as a figure of fun, alongside the narrator. This is our shared moral shortcoming. We prefer to laugh at people who embrace death rather than accept it head on. The narrator’s moral shortcoming is that he treats Con with contempt, not thinking for a minute that he might learn something from the old man. (Until he does.)

DESIRE

The narrator deals with Con by turning him into a figure of fun, but his deeper psychological shortcoming is that he finds death terrifying. Better not to think about it.

‘Not thinking about it’ is in line with what the surrounding (Western) culture expects in regards to death. Talking about death when the deceased is not directly related to oneself equals ‘revelling in it’. There’s the line between appropriate and inappropriate smalltalk. Con crosses it, failing to heed any negative social cues.

OPPONENT

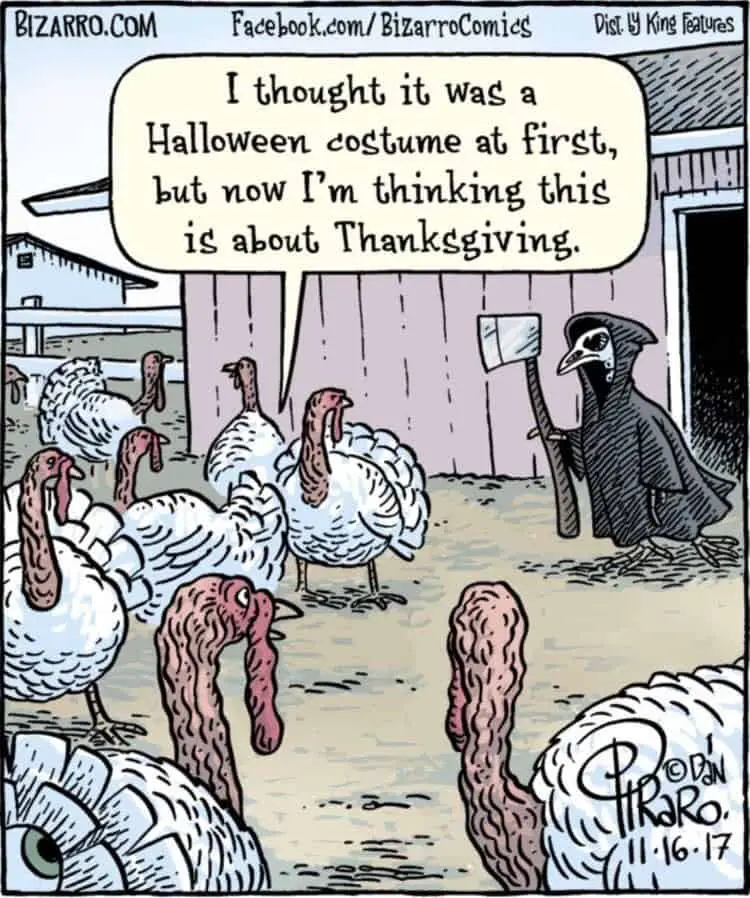

Since the narrator does not want to think too much about death, and since Con won’t shut up about it, the two are in opposition to each other. Of course, Con McCarthy is the comical real-world equivalent of the supernatural figure of the Grim Reaper. It’s not Con who is the main opposition — the real opponent is death itself.

MYTHOLOGY OF THE GRIM REAPER

Death has long been personified in fairytale and folklore. The Grim Reaper plot was a popular one for the medieval writers of jests and fables:

Death promised a man that he would not take him without first sending messengers. The man’s youth soon passed and he became miserable. One day Death arrived, but the man refused to follow him, because the promised messengers had not yet appeared. Death responded: “Have you not been sick? Have you not experienced dizziness, ringing in your ears, toothache, and blurred vision? These were my messengers.” The man, at last recognizing the truth, quietly yielded and went away.

Retold from Death’s Messengers, Grimm, no. 177, type 335.

The Grim Reaper is most often a terrifying figure, but Kevin Barry has inverted the terror here and made him into a figure of fun.

The way Kevin Barry depicts this old man as a supernatural figure is masterful. It is achieved partly by painting him as timeless and unknowable:

He did not seem to hold down a job. (It was hard to imagine the workmates who could suffer him.) His occupation, plainly, was with the dead. It was difficult to age him. He was a man out of time somehow. The overcoat was vast and worn at all seasons and made him a figure from a Jack B Yeats painting or an old Russian novel. There was something antique in his bearing.

The rain that he drew down upon himself seemed to be an old, old rain.

THE COMEDY OF “WHO’S-DEAD MCCARTHY”

To that end, what are the exact comedy mechanisms at play?

- A lot of situational comedy relies upon expected gags which play out in almost exactly the same way time and again. In Keeping Up Appearances it’s Hyacinth being surprised by the dog in the car, and throwing herself against the hedge. It’s funny because we know it is coming. Occasionally it’s subverted. Likewise, Catherine Tate’s sketches rely heavily on audience expectation, as do the sketches in Little Britain. It doesn’t take long to set these up. Twice is enough. In “Who’s-Dead McCarthy” the author sets up a fully expected script with several repetitions of the same conversation. This becomes inverted in the final sentence. This example of common comedic set-up reaches beyond comedy, however — the key is in the flip at the end. The narrator has become the figure of fun, and is now at the mercy of death himself. Moreover, the fact that the reader ‘expects’ what’s coming mirrors how we ‘expect’ death to come to each and every one of us, but we don’t know exactly what ‘the author’ (fate) is going to do with it in our own particular sketch. We know we’re going to die. We don’t know exactly when and how. This is its own kind of comfort and delight.

- Con McCarthy is turned into a comedic character partly due to melodrama.

“Elsie Sheedy?” he’d try. “You must have known poor Elsie. With the skaw leg and the little sparrow’s chin? I suppose she hadn’t been out much this last while. She was a good age now but I mean Jesus, all the same, Elsie? Gone?”

His eyes might turn slowly upwards here, as though in trail of the ascending Elsie.

(Notice how the author repeats the melodrama in the final sentence, with the same image of the eyes slowly moving up: ‘I let my handsome eyes ascend’. Why ‘handsome’? That word pulled me up short the first time I read it. This is the narrator now viewing himself from another plane. His younger self would of course be ‘handsome’. He is also seeing himself as an actor on a stage.

- The comedy in this short story shares something in common with the comedy in many picture books; ie. the story goes as far as you think it could possibly go, but the author has the skill of taking us that one extra step further. A picture book example is Stuck by Oliver Jeffers. Just when you think nothing more ridiculous could get stuck in a tree, something does. In “Who’s-Dead McCarthy”, the ‘one more miserable thing tacked onto the end of great misery’ transforms the story-within-the-story of the bull attack from a sad story into a hilariously sad story, because it is revealed the family were watching. The added touch ‘They’ll never be right’ is the flourish that actually made me laugh. The epitome of gallows humour.

PLAN

Sometimes ‘plans’ are a matter of avoidance, eventuating in an expression borne of exasperation.

By the time the narrator confronts Con, I’m sure he’s thought of saying all those things to him many times before. Finally it’s out. But for storytelling purposes, this was the narrator’s ‘plan’.

BIG STRUGGLE

Exasperated, the narrator has confronted Con, and delivers what we all assume will be a cutting blow: Nobody wants to hear you talk, Con. We cross the road to avoid you.

Imagine being told that everyone hates you, basically. This is one of the greatest blows a human can suffer.

ANAGNORISIS

But Con does not respond as expected, by getting upset with the narrator, feeling shunned, suffering hurt. It becomes clear to the reader (and to the narrator) that Con’s fixation with death has somehow elevated him above earthly conventions like ‘fitting in by small-talking about frippery’. He has moved to a higher plane, confronted by his own old age and imminent death, where the spectre of finality causes worldly concerns to shrink permanently into insignificance.

“Can I ask you something?”

“What?”

“Why are you so drawn to it? To death? Why are you always the first with the bad news? Do you not realise, Con, that people cross the road when they see you coming? You put the hearts sideways in us. Oh Jesus Christ, here he comes, we think, here comes Who’s-Dead McCarthy. Who has he put in the ground for us today?”

“I can’t help it,” he said. “I find it very … impressive.”

“Impressive?”

“That there’s no gainsaying it. That no one has the answer to it. That we all have to face into the room with it at the end of the day and there’s not one of us can make the report after.”

NEW SITUATION

The narrator now shifts his own way of looking at the world. In a sense he becomes Con, next on the chopping block.

I BECAME MORBIDLY FASCINATED by Con McCarthy.

Whereas Con is obsessed with death, the narrator becomes obsessed with Con’s obsession with death.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Another short story in which the narrator becomes like another character originally despised is “Sucker” by Carson McCullers, written when she was seventeen. In both cases there is a verbal confrontation as Battle scene, followed by an unexpected reaction, followed by a body-swapping plot, though only in the psychological sense.

Header photo by Yomex Owo