“Whistler’s Grandmother” by Shirley Jackson was published in the May 5, 1945 edition of The New Yorker. Find it also in the collection Just An Ordinary Day (1996).

Rowan Atkinson took the comical route when referring to the painter Whistler. I have to agree, the name “Whistler” lends itself well to comedy. As you may remember, if you’ve seen Bean: The Movie (1997), Mr Bean works as a security guard at the National Gallery in London before being sent to the United States to talk about the unveiling of James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s 1871 invaluable painting “Whistler’s Mother”. As you’d expect, disaster visits upon the painting.

But what did American horror writer Shirley Jackson do with this famous painting in her WW2 era short story? (Also, does the war have anything to do with this? Does Jackson’s story have anything to do with the painting, for that matter?)

My favourite James Abbott McNeill Whistler painting is “Nocturne in Green and Gold”, which has a beautifully horror feeling to it, don’t you think?

WHAT HAPPENS IN “WHISTLER’S GRANDMOTHER”

A charming little old woman is visiting New York on the train. She hasn’t visited New York in fifteen years, she announces to passengers within earshot. She’s coming to visit her grandson, who is a returned solider. (There we go, there’s the war link.) She also intends to tell him that his wife hasn’t “played fair” while he was away fighting.

How does she know this? The pretty wife wears racy clothing. And when she came to stay with the old lady upstate, she received letters from men. How does she know the letters were from men? She knows what male handwriting looks like. (Once again, Shirley Jackson is using one of her favourite ways of creating trouble between characters: letters.)

Travel companions try to reason with the uncharitable old woman. Clearly, they don’t believe anything has happened, for sure. However, the little old lady insists.

SHOULD YOU TELL SOMEONE IF THEIR PARTNER IS CHEATING ON THEM?

This question is the regular topic of advice columns. I always like the advice of Captain Awkward (American), e.g. Should I tell my friend her boyfriend is cheating on her? She has a history of shooting the messenger. Another one is Should you tell someone if you know they’re being cheated on? at The Hook Up podcast (Australian). Basically, thoughtful people tend to agree that it really depends on the situation, partly because you may not be the best person for the job. You should to know the person well and be sure of what you know. Sometimes the receiver of bad news does shoot the messenger, but as Captain Awkward says, “one thing that makes a person jealous and insecure is CONSTANT JERKY CHEATING BY PEOPLE YOU TRUST.”

SHOULD THIS OLD LADY TELL HER GRANDSON?

Clearly, no. Shirley Jackson gives us sufficient clues to convey the reality that the old woman is wrong. But the truth of the situation is secondary to Jackson’s social commentary regarding

- What people are capable of assuming from very little information

- How people’s own attitude influences their read of a situation

- How people’s own gender influences their read of a situation

Note that good writers must be aware of cognitive biases, because storytelling relies on cognitive bias. Even at a conversational level, we never explain every single detail of a story. We are reliant upon our interlocutors putting two and two together to make four.

Therefore, when storytellers write stories which critique cognitive bias, they are generally doing something subversive and meta and Postmodern (in which there’s no such thing as the truth, only varying perspectives on it).

THE GRANDMOTHER’S EGO-CENTRIC BIAS

Egocentric bias is the tendency to rely too heavily on one’s own perspective and/or have a higher opinion of oneself than reality.

We are far more likely to think of how we are affected than how we affect others. This grandmother is salty because she wanted the grand-daughter-in-law to stay with her upstate, but (utilising a fill-in-the-gaps cognitive bias of my own), I deduce when the young woman turned down her offer, she became vengeful.

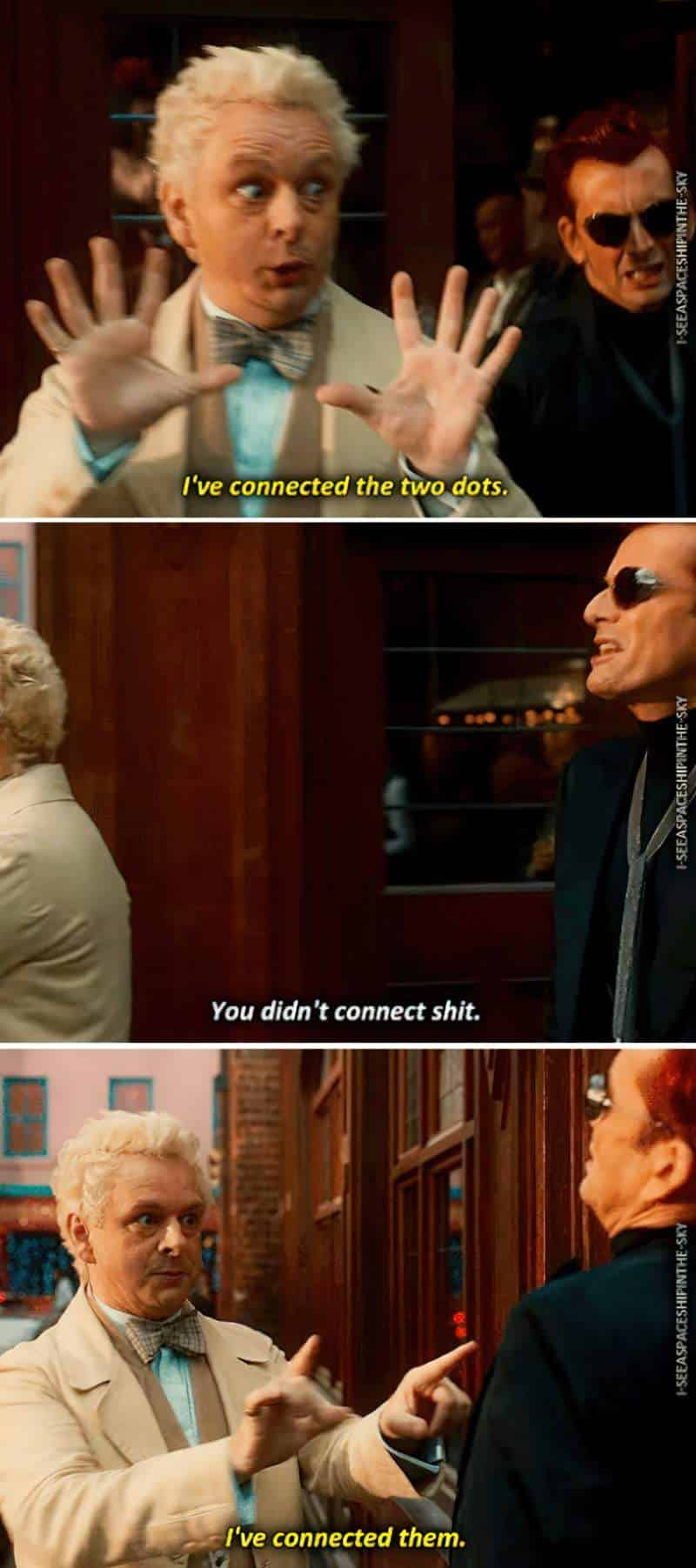

I very much doubt this elderly woman has the self-insight to connect the dots between her own disappointment and loneliness and her interpretation of cheating. She has connected the dots (probably incorrectly) for the younger daughter, but does not connect the dots when it comes to herself.

When I say ‘connect the dots’ I’m talking about Gestalt Theory, in which our brains rearrange things so that they make sense.

IN-GROUP BIAS

Notice how quick the solider believes the grandmother’s take on the situation. He clearly positions himself in the shoes of the husband:

That’s not very nice of her,” one of the soldiers said.

“Whistler’s Grandmother” by Shirley Jackson

It’s not until the young woman speaks up that the soldiers also start to doubt the veracity of the story. Note also, that although the young woman is the passenger to start the men doubting, the men aren’t really letting her speak. They’re clearly hearing her without knowing they’re hearing her:

“Maybe you’re mistaken about her,” the younger woman said. “It’s so easy to make a mistake about people.”

“True is true,” the old lady said. “My grandson’s wife, she stayed with me awhile upstate. She used to get letters from men.”

The younger woman started to say something and then stopped, and the man said, “How do you know?”

“Whistler’s Grandmother” by Shirley Jackson

Today, now that women have entered the workforce in large numbers, women talk about gendered experience in meetings, about saying something only to be ignored. A man then says exactly the same thing and people respond to him. Meanwhile, the man who repeats what he hears from the woman doesn’t seem to realise the voice didn’t originate from inside his very own brain.

Women first start experiencing this phenomenon in childhood, in fact, especially if girls go to co-ed schools. This situation may resonate: A girl will crack a joke; everyone ignores her. A boy repeats the girl’s joke (often in a louder voice) and this time everyone laughs. Importantly, for this to work, a large proportion of the other girls must have learned to prioritise male contributions. By high school, this will have happened.

In this story, it’s not clear that the woman has been cut off by a man. It seems she has simply stopped speaking, perhaps thinking better than to interfere. But after a lifetime of being interrupted, women start to self-censor. Women stop talking so confidently, subconsciously handing the more direct communications over to men, who are then perceived as smarter, more direct, more assertive and more capable.

Once you notice this phenomenon, you see it everywhere. If you don’t, you don’t. It’s always interesting to see it depicted in older fiction, which shows this dynamic is old as the hills, and that women have been noticing it all along. It would seem Shirley Jackson understood gendered social dynamics very well, as did other woman writers such as Katherine Mansfield (evinced in “A Dill Pickle,” for instance.)

Note that gender of the individual does not predict misogyny. The elderly woman is a misogynist through-and-through. Importantly, Shirley Jackson has dressed her in a black coat, not because she’s attending a funeral, but because she disapproves of showy clothing. And by showy, she simply means 1940s fashion. The woman in question wears a flowery dress. More significantly, she is ‘pretty’. No matter what a young woman wears, she will be sexualised. (Sexualisation is different from sexuality.)

In her third book, Sexed Up, Julia Serano focuses her brilliant mind on sexualization, “when a person is non-consensually reduced to their real or imagined sexual attributes,” and how this process results from what she identifies as five mindsets that binarize how we perceive and interpret people.

Advocate

In reality, a woman doesn’t even have to be pretty to be sexualised. As Serano writes in her book, in order for sexualisation to happen, a person only need be read as femme (or queer) and young. (As femmes get older, invisibilization and desexualisation kicks in.) Hence the divide between the ages of these fictional women created by Shirley Jackson to illuminate the dynamic. It’s highly likely this elderly woman on the train (“Whistler’s Grandmother”) experienced sexualisation when she was a young woman herself. So what gives? Why are some old women like this?

I can make up a backstory for Jackson’s old woman because there’s nothing original or unexpected about it: We recognise these people. In the 1940s, they would have proliferated. This old woman believes women are the gatekeepers of sex while men take what they can, whenever they can. (Serano also talks about this in Sexed Up, as have many others, though Serano refines the vocabulary a little, introducing the concepts of marked versus unmarked people. Marked people are “public spectacles”.) By this way of thinking, it is a woman’s job to desexualise herself and protect herself from “predatory men”. Hence the reason Jackson has dressed this old woman in a black coat. But even a coat isn’t enough to save you. This old woman expects the younger one to have nothing to do with unrelated men, living in a completely gender-segregated world. If asked, the old woman might grudgingly agree that women are needed in factories and whatnot during the war, but she would advise women return to the home as soon as the soldiers return. Men need their jobs back, and women are safest there.

Importantly, the old woman has not visited New York in fifteen years, despite living just upstate, and despite having a grandson who she might visit. This suggests she, herself, keeps her life very small. It would explain why she craves the company of another woman in the house.

The detail about not having visited in fifteen years is significant in that we can also deduce she does not know her grandson at all. He is a stranger to her. To underscore this detail, Jackson shows us that the grandmother has no idea where he’s stationed. She contrasts that with the older man on the train, who knows exactly where his sons are stationed when queried by the soldiers.

WHAT’S WITH THE “WHISTLER” REFERENCE OF THE TITLE?

Why Whistler’s Grandmother? Is there a link to the painting?

Well, let’s take a look at Anna McNeill Whistler, who also wears a black coat and an old lady’s hat. Clearly, Shirley Jackson would like us to imagine an even older, almost ghost-like version of Whistler’s Mother — a woman who cannot/will not move with the times: An era of increasing freedom for women, who during the wars were permitted (required) to leave the domestic sphere and intermingle with a wider community of people.

The old woman in Whistler’s famous painting looks as if she’s sitting primly on a train. Imagine the framed picture as window. The train setting is symbolic: When people are on a train, there’s a fatalistic vibe to a story. Jackson writes of how the train ‘plunges’ into a tunnel. We know at this point that the old lady is not about to change her mind, and can extrapolate that the situation with her grandson is about to get very dark.

Importantly, Anna Whistler blends into the background. Whistler’s radical method of modulating tones of single colours was influential.

The significance for Jackson’s story: Like old ladies everywhere, this little old lady is in danger of becoming invisibilized (that is, unless she makes her presence known by interfering in her grandson’s business, and talking loudly to all and sundry on a commuter train).