What are the common features of popular works commonly described as ‘whimsical’? A long while ago I swapped a middle grade critique with someone who had used ‘whimsical’ in the title of their work, yet the story itself did not feel whimsical. I started to wonder about the unspoken rules of ‘whimsical’. But could I be wrong about ‘whimsical’? What what does whimsy mean? Is it possible to list the attributes of this aesthetic?

Here are some examples of how ‘whimsical’ is often used in the marketing copy of books:

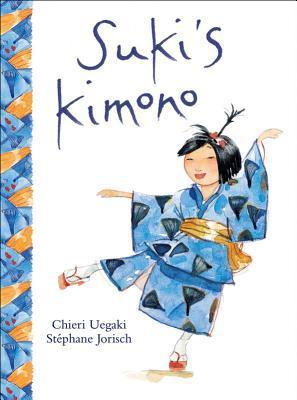

Suki’s favorite possession is her blue cotton kimono. A gift from her obachan, it holds special memories of her grandmother’s visit last summer. And Suki is going to wear it on her first day back to school — no matter what anyone says.

When it’s Suki’s turn to share with her classmates what she did during the summer, she tells them about the street festival she attended with her obachan and the circle dance that they took part in. In fact, she gets so carried away reminiscing that she’s soon humming the music and dancing away, much to the delight of her entire class!

Filled with gentle enthusiasm and a touch of whimsy, Suki’s Kimono is the joyful story of a little girl whose spirit leads her to march — and dance — to her own drumbeat.

MARKETING COPY

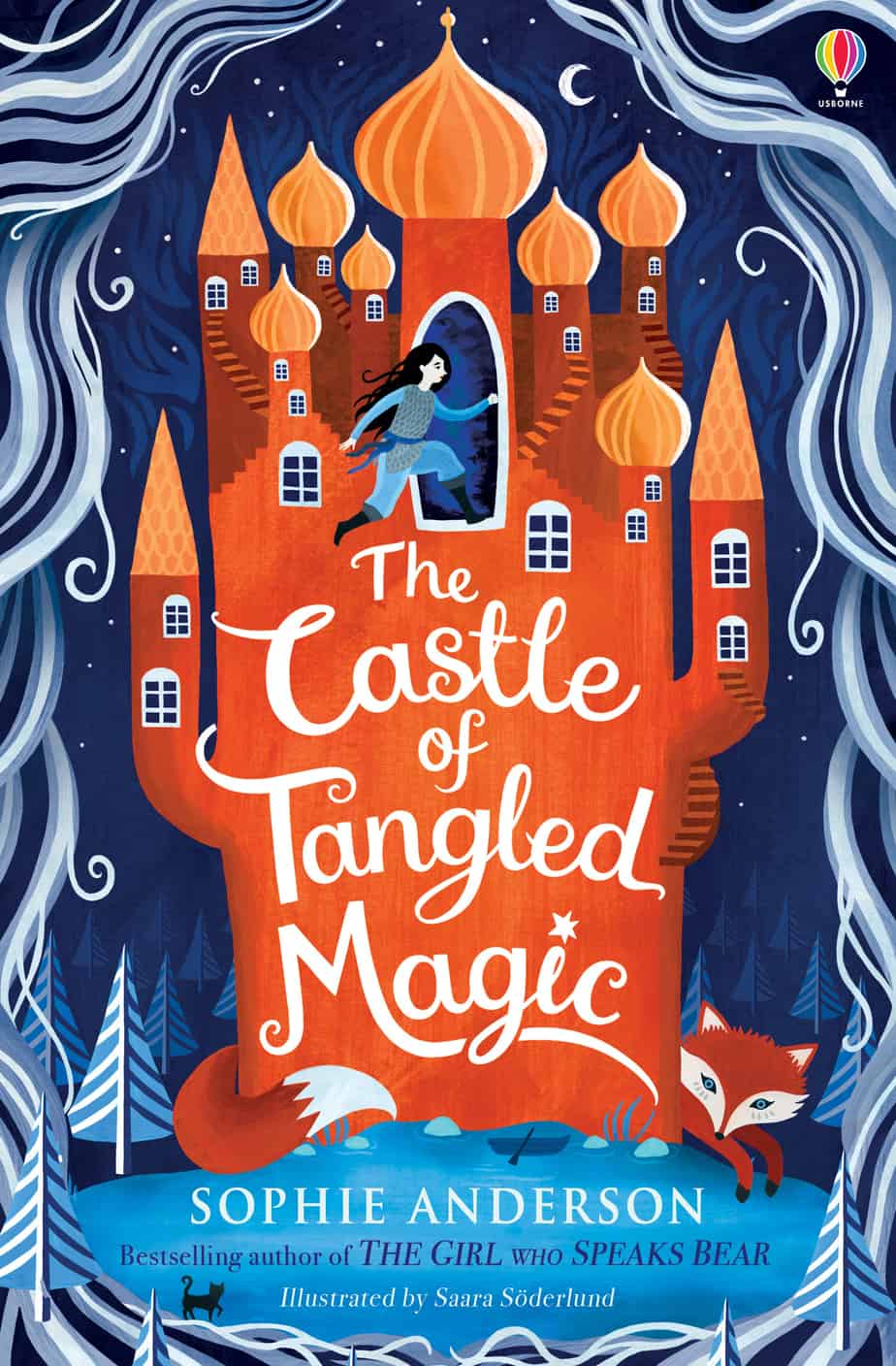

Magic and whimsy meet in this Howl’s Moving Castle for a new generation from the critically adored Sophie Anderson, author of The House with Chicken Legs.

Twelve-year-old Olia knows a thing or two about secrets. Her parents are the caretakers of Castle Mila, a soaring palace with golden domes, lush gardens, and countless room. Literally countless rooms. There are rooms that appear and disappear, and rooms that have been hiding themselves for centuries. The only person who can access them is Olia. She has a special bond with the castle, and it seems to trust her with its secrets.

But then a violent storm rolls in . . . a storm that skips over the village and surrounds the castle, threatening to tear it apart. While taking cover in a rarely-used room, Olia stumbles down a secret passage that leads to a part of Castle Mila she’s never seen before. A strange network of rooms that hide the secret to the castle’s past . . . and the truth about who’s trying to destroy it.

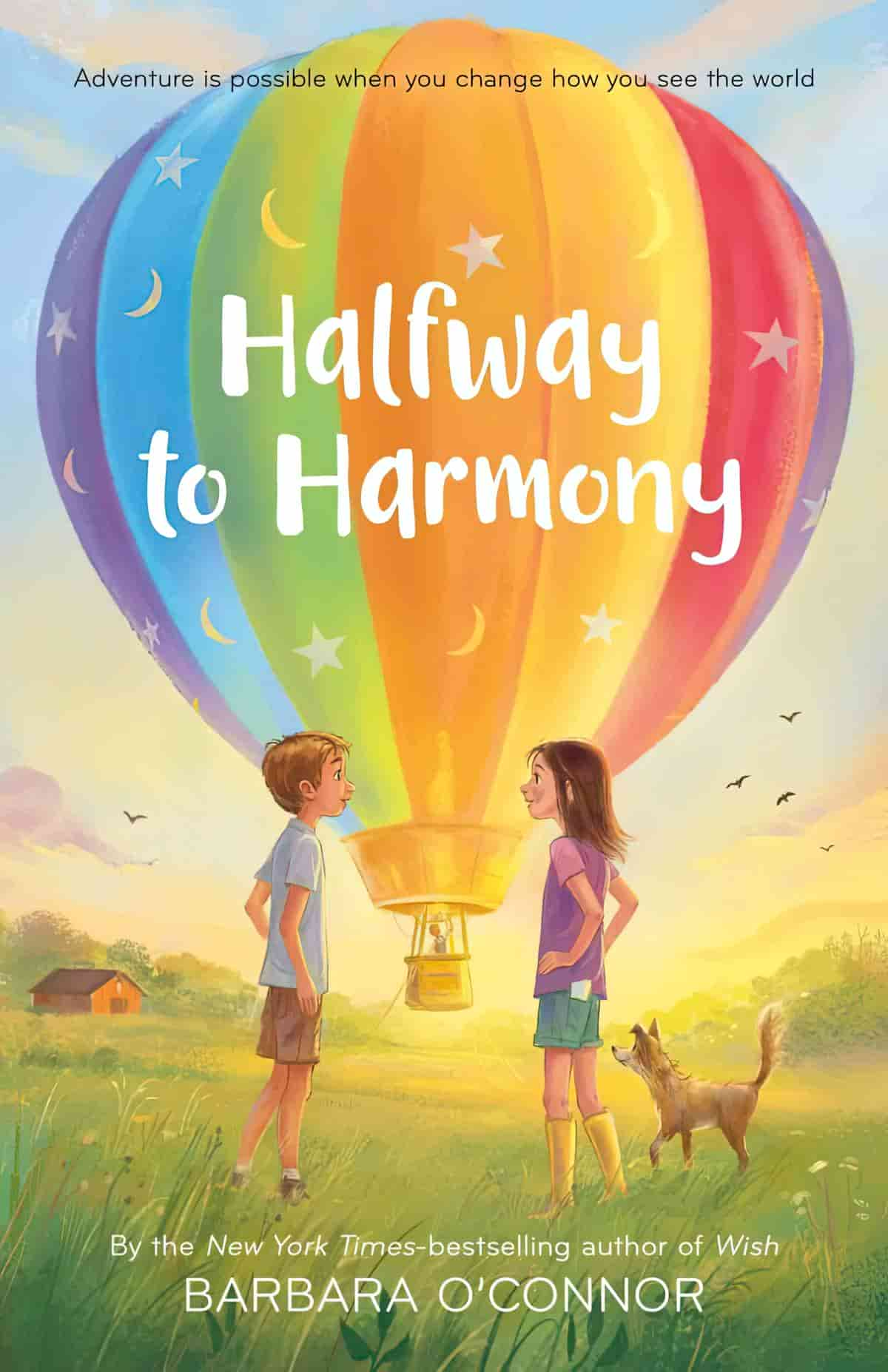

A heartfelt middle-grade novel from New York Times bestselling author Barbara O’Connor about a boy whose life is upended after the loss of his older brother–timeless, classic, and whimsical.

Walter Tipple is looking for adventure. He keeps having a dream that his big brother, Tank, appears before him and says, “Let’s you and me go see my world, little man.” But Tank went to the army and never came home, and Walter doesn’t know how to see the world without him.

Then he meets Posey, the brash new girl from next door, and an eccentric man named Banjo, who’s off on a bodacious adventure of his own. What follows is a summer of taking chances, becoming braver, and making friends–and maybe Walter can learn who he wants to be without the brother he always wanted to be like.

Halfway to Harmony is an utterly charming story about change and growing up.

This French book by Camille Jourdy is part of a series described as ‘whimsical’ in French about a girl who goes into the forest and encounters fantastic creatures called Les Vermeilles.

DICTIONARY DEFINITION OF WHIMSICAL

1a: resulting from or characterized by whim or caprice especially: lightly fanciful whimsical decorations b: subject to erratic behavior or unpredictable change

2: full of, actuated by, or exhibiting whims

In modern English, ‘whim’ is a sudden desire or change of mind, especially one that is unusual or unexplained. Although ‘whimsical’ tends to describe a person, I suspect when talking about story structure, ‘whimsical’ refers not so much to the attributes of the main character but to the type of surprise in the plot. A ‘whimsical’ plot probably relates specifically to the plans characters make in response to events: While all good stories contain elements of surprise, ‘whimsical’ plots take readers in completely unexpected directions when main characters make completely unexpected decisions.

Today I will take a look at several whimsical examples of children’s books, as described by both consumer reviewers and marketing copy: mostly Furthermore by Tahereh Mafi (2016) — a middle grade novel and occasionally How To Make Friends With A Ghost by Rebecca Green (2017) — a picture book which I have analysed separately for its story structure.

WHIMSICAL CHARACTERISATION

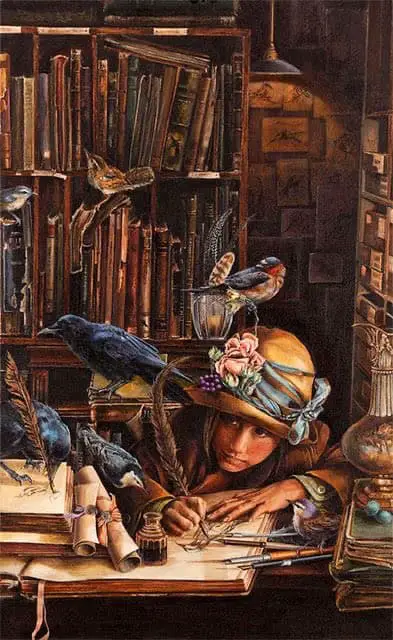

In graphic art, a whimsical aesthetic tends to include: girls and young women (and anything associated with the feminine ie. birds); a shabby and cluttered but warm environment, suggesting a character who doesn’t care too much about appearances and housework; and an eccentric and individualised sense of style. ‘Whimsical’ and ‘quirky’ go hand-in-hand.

THE NAMING OF WHIMSICAL CHARACTERS

First of all, the names. In Furthermore we have amalgamated names:

- Alice Alexis Queensmeadow (Queens + Meadow)

- Oliver Newbanks (New + Banks)

In whimsical fiction, the names of the characters are oftentimes recognisable words put together to form new combinations. Queens + Meadow, New + Banks. This is in contrast to high fantasy, where the names are new combinations of phonemes, not amalgamations, blends and portmanteau words.

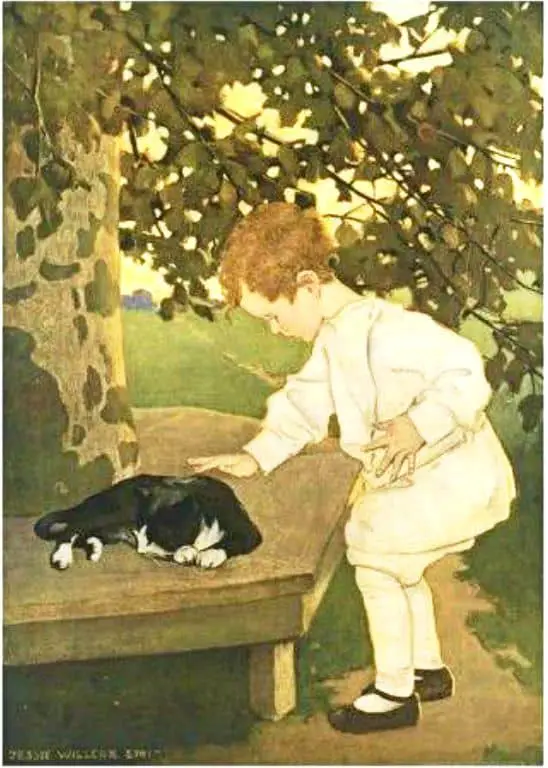

Whimsical main characters tend to be:

- Positive even in dire circumstances

- Main characters tend to be female and full of childlike wonder.

- Whimsical characters have a special affinity with animals and nature in general.

- They are caring and exhibit kindness.

Characters In Furthermore

- Alice of Furthermore somehow thinks that ‘ being quiet meant being invisible’.

- She likes to dance with abandon (in fact this is what she considers to be her special skill). She exaggerates, and doesn’t seem to have a good sense of time and distance. ‘They walked for days. Weeks. Months and years. “Don’t be so dramatic,” Oliver said. “It’s only been fifteen minutes.”

- She is curious to a dangerous degree, unaware of the dangers of her new world.

- She doesn’t have much self-control — acting on the spur of the moment: ‘He’d touched her arm, so, really, she had no choice but to punch him.’

- Alice runs home to mother with dishevelled skirts and grass in her hair.

- Alice is capricious: ‘She would win the Surrender and she would show Mother she could make her own way in the world and she would never need a pair of stockings again. She would be an explorer! An inventor! No—a painter! She would capture the world with a few broad strokes!’ At the beginning of the story she doesn’t know who she is. This is a mythical journey with a coming-of-age arc.

- In Furthermore the gender binary is less enforced than in other works. Alice is approaching a non-binary characterisation. Likewise, Oliver could just as easily be a girl. Alice’s love interest has ‘very short shorts’ and is beautiful in an androgynous way. Sexuality is not at the fore in whimsical fiction, though crushes and attraction may be there.

- Alice never speaks unkindly to anyone, even if she does sometimes succumb to benign violence. There is zero swearing in a whimsical book, and an almost grandmotherly quality: ‘Oh, she would be sleeping with the pigs tonight.’ ‘If this wasn’t an emergency Alice was a dill pickle.’ ‘You wear arrogant and unkind and a horrible, raging skyhole.’

- Alice is upbeat: ‘The pigs weren’t so bad. They were warm and shared their straw and made little pig noises that helped Alice relax.’

- Alice only eats flowers and has an affinity with the pigs she is required to sleep with. If she eats eggs, she makes a swap with the chickens, likewise cows for milk. There is quite a strong vegan message in it, underscored when she enters a less kind world where the characters eat animals.

THE CHARACTER OF HOW TO MAKE FRIENDS WITH A GHOST

The main character of How To Make Friends With A Ghost remains unnamed. She is clearly a motherly figure who is told by an unseen expert how to look after a cute ghost. The history of gendered toys in itself shows how we tend to spend more time teaching girls how to be kind than we do teaching boys. Take tea sets, a gift often given to girls and rarely to boys. Serving tea to dolls and teddies is fun, and also serves the social purpose of teaching young children to serve others in kindness.

No surprise, then, that stories mainly about kindness and friendship so often feature girls. And no surprise, either, that stories described as whimsical are also often about girls.

THE BAKED-IN FEMININITY OF WHIMSICAL STORIES

Returning now to the dictionary definition of ‘whimsical’, there’s a good dose of capriciousness baked into the concept, in which a character seems to frequently change their mind. I say ‘seems to’, because we shouldn’t make the mistake of thinking that simply because we didn’t anticipate someone changing their mind, doesn’t mean their motivations are mysterious. All that means is that we weren’t able to anticipate them, probably because we aren’t sufficiently acquainted with their shortcomings, desires and plans, possibly because we are of a different background and demographic ourselves. Or perhaps we’ve pai them no mind at all, because we don’t consider them worthy of our time and attention.

Now to that old chestnut: It’s a woman’s right to change her mind.

This phrase has been used (mainly by men) as a criticism (sometimes mild, sometimes a rebuke), and has also been used by women to remind male partners that, yes, women are allowed to change their mind, at any stage, and be respected for her reasons even if those reasons are not understood.

I push back against the idea that, in the real world, women change minds more often than men change their minds. But what of fictional characterisations?

If we take the ‘Plan‘ stage of any story, it tends to go like this:

Based on their own psychological and moral shortcomings, guided by their desire to achieve a certain story-worthy goal, the main character of a story make plans. The opposition rises up to stop the main character from carrying out their plans. Main character must now change plans. The longer the story, the more often this happens. In a feature-length film, it’ll typically happen three or four times as the opponent reacts and ups the ante on their part.

To put that another way, fictional characters in all kinds of work are frequently changing their minds. To change one’s mind is to change one’s plan. It is only when the plan seems incomprehensible (to us) that it also seems ‘whimsical’.

Are the whimsical characters of whimsical stories behaving any differently from the multitudes of main characters constantly forced to change and modify their plans? I argue that it’s not the frequency of the change-of-plan that makes a character feel whimsical, nor is it the unexpectedness: It’s the quirkiness of the plan.

As mentioned above, ‘quirky’ is a very similar word to ‘whimsical’, and once again skews female.

Both words describe the unexpected. When a story doesn’t pan out as ‘expected’, that’s probably because the storyteller is working with something other than the linear masculine mythic form which has dominated for the last 3000 years of human history. The storyteller may be working with the much more recent Female Mythic form, in which case expectations for a face-to-face battle will be subverted as the main character (of any gender) thinks their way through a problem rather than fighting against the Minotaur. The whimsical story tends to be about friendship, kindess and co-operation instead of individualism, heroism and conflict. Hence, the Female Myth is more likely to be coded as whimsical.

Along with Female Myths, other experimental forms are likely to earn the description of ‘whimsical’. How To Make Friends With A Ghost is a good example of that.

WHIMSICAL SUBJECT MATTER

- Royalty (Queens, Princesses, Kings)

- Natural settings

- Flowers (Alice of Furthermore eats them.) Come to think of it, anything strongly associated with fairies tends to feel whimsical.

- Meaningful Skies (Clouds are certain shapes, and can be sat upon; shooting stars are linked to wishes)

- Related to the clouds is the moon. The moon is probably significant in your main character’s life somehow — indicating excitement and that something’s about to change, and probably associated with magic.

There’s a synesthesic quality to Furthermore, where magic and colour are very much one and the same. Other examples:

Her bangles mimicked the rain, simple melodies colliding in the space between elbows and wrists. She closed her eyes. She knew this dance the way she knew her own name; its syllables found her, rolled off her hips with an intimacy that could not be taught.

He wore boots so shiny Alice swore she heard them glitter.

When Alice closes her eyes, this signals that she is using other senses. It’s important when writing anything not to rely solely on the sense of sight, but in whimsical writing you can really stretch this, combining metaphor with various senses to create an image the reader can’t quite put their finger on, but evocative all the same.

WHIMSICAL SETTING

TV Tropes lists a category called ‘Wackyland‘, which is sort of like Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland, where nothing makes sense (absurdism). To create the absurd is one way of working towards a whimsical setting. No coincidence that the main character in Furthermore is also called Alice. The reader never really understand how the magic in this world works. It just does. The magic system itself is capricious.

The whimsical story is perfectly suited to the inbetween (liminal) seasons, especially autumn. Winter is also great, so long as the characters can cosy up somewhere in their sweaters and rugs, drinking hot cocoa. The whimsical storyworld is quite often a celebration of hygge.

The whimsical setting is quite often atemporal and without an exact geolocation, same as the fairytale landscape. Even when set in the real world, it will likely include fantasy elements (fabulism/magic realism).

WHIMSICAL VOICE

Furthermore is told to us by an off-the-page, third person narrator. This narrator addresses the reader directly and has a personality of their own. For a description of ‘dissonant’ and ‘consonant’ narrators, see What Is Psycho Narration?

The dissonant narrator of Furthermore has no sense of time and draws attention to the fact that some parts of the story are boring, so those parts will simply be skipped, and to the fact that at times they’re not a particularly good storyteller, and don’t know what to call the chapters.

- ‘(I’ll explain why later)’

- Alice’s and Oliver’s stories are already familiar to you, so I won’t bother relating them all again

- Dear reader: I do hope you enjoy a happy ending.

This voice is also reminiscent of fairytale language, opening with ‘Once upon a time, a girl was born.’ But the author switches gears immediately in the second sentence, with a juxtaposition suggesting humility: ‘But it was rather uneventful.’

Words such as ‘rather’ are reminiscent of formal, stiff, upper-class English narrators, and the author very much means to draw attention to these words. The title of the book (and the name of the fantasy land) is ‘Furthermore’, a word only really used in writing or by adults. Characters are named after these words, too, such as the blue boy love interest.

Original colocation of words is also important in Furthermore, in not only creating the sense of a different world and language, but of a childlike voice. If you’ve spent much time around preschoolers, you’ll be familiar with their habit of making up their own arrangements of words until they interalise the idiosyncratic conventions of English. When fictional characters do the same thing, it makes them sound both youthful and like someone from another world:

- ‘The annual Surrender was only a single pair of days away‘ (Not ‘two days away).

- ‘Alice dropped her head, because sadness had left hinges in her bones.’

- ‘She wanted Mother to grow up—or maybe grow down—into the mther she and her brothers really needed. But Mother could not unbecome herself’

The messages in the book about how to live a good life are also of a whimsical nature:

“I don’t know, but not knowing is only temporary when we have the minds to figure it out.”

What makes this whimsical? I believe it’s the upbeat, relentlessly positive nature of the assertion.

Moving now to How To Make Friends With A Ghost, part of the whimsy derives from the narrational irony. In a cosy supernatural story, the writer has chosen the voice and style of a how-to guide. The formality of your typical how-to guide serves to highlight the capricious fun of a carnivalesque, imaginative romp in which it were indeed possible to make friends with a ghost.

WHIMSICAL SENSE OF HUMOUR

In this post I looked closely at children’s humour, using the taxonomy as described by CEO of The Onion. But none of the examples in that post go anywhere near describing the sort of humour you encounter in whimsical fiction. Take the following sentence, which is funny in a low key way:

It was hard for Alice to like Oliver — on account of she didn’t like him very much — but she wanted to find Father much more than she didn’t like Oliver, so she’d have to put up with him.

Furthermore

It’s not easy to describe why this is funny, but it has to do with:

- Juxtaposition of the formal style and subtextual wish to be nice against the childlike declaration of simply not liking someone

- The repetition

- Most of all the deliberate tautology — or the petitio principii (related to the original meaning of ‘begging the question’). “I don’t like him because I don’t like him.”

All parts of this joke convey to the reader a narrator (and main character, who may well be telling her own story about herself for all we know) who is muddle-headed, flawed but harmless and… well…. whimsical.

The following joke is similar:

She followed Oliver as he went and asked no additional questions outside of the five questions she did ask, and paused only to sneeze when her nose required it.

Furthermore

She didn’t ask any questions, except five more — a sentence contradicting itself. In the second part of the sentence it seems our whimsical main character considers her nose to have a life of its own. Both parts of this sentence emphasise youthfulness and a character not quite in control of the situation, or even of her own body.

Alice thought maybe she should scream—it seemed like the right thing to do—but it didn’t feel honest.

Furthermore

Whereas ‘screaming’ is (in certain circumstances) an involuntary act, Alice makes it sound like screaming is something you choose to do or not according to circumstance. Yet earlier she didn’t seem to be in control of her own nose or ability to stop asking questions. Because screaming often happens in stories whenever something frightening has happened, Alice’s consideration of whether she should scream or not also has a metafictive tinge to it — we are reminded once again that this is a story. If we are reminded this is a story, we are reminded that we are perfectly safe (even if our characters are not). Whimsical fiction — and humour — is ‘safe’.

Oliver had said that falling in Furthermore was too anticlimactic to be deadly.

Alice finds herself in a 2D town, herself turned to paper and her arm ripped off:

Alice had already lost a father, the length of her right arm, and an entire set of bangles, so it made sense that her voice would follow suit.

This is funny because it lists a series of terrible things (losing a parent, losing a limb) and puts something relatively inconsequential at the end (losing bangles) of the list as if it carries the same weight.

WHIMSICAL ART AND DECORATION

- stars, curlicues

- swirls in general

- floral patterns

- any sort of folk art decoration

- rich, warm colour palettes

- the hand of the artist is often evident. with realworld media (or digital emulation of realworld media) preferred over the hyperpolished digital art look

- deliberately off-kilter perspective

- font may have a hand-lettered look, or an old typeset look

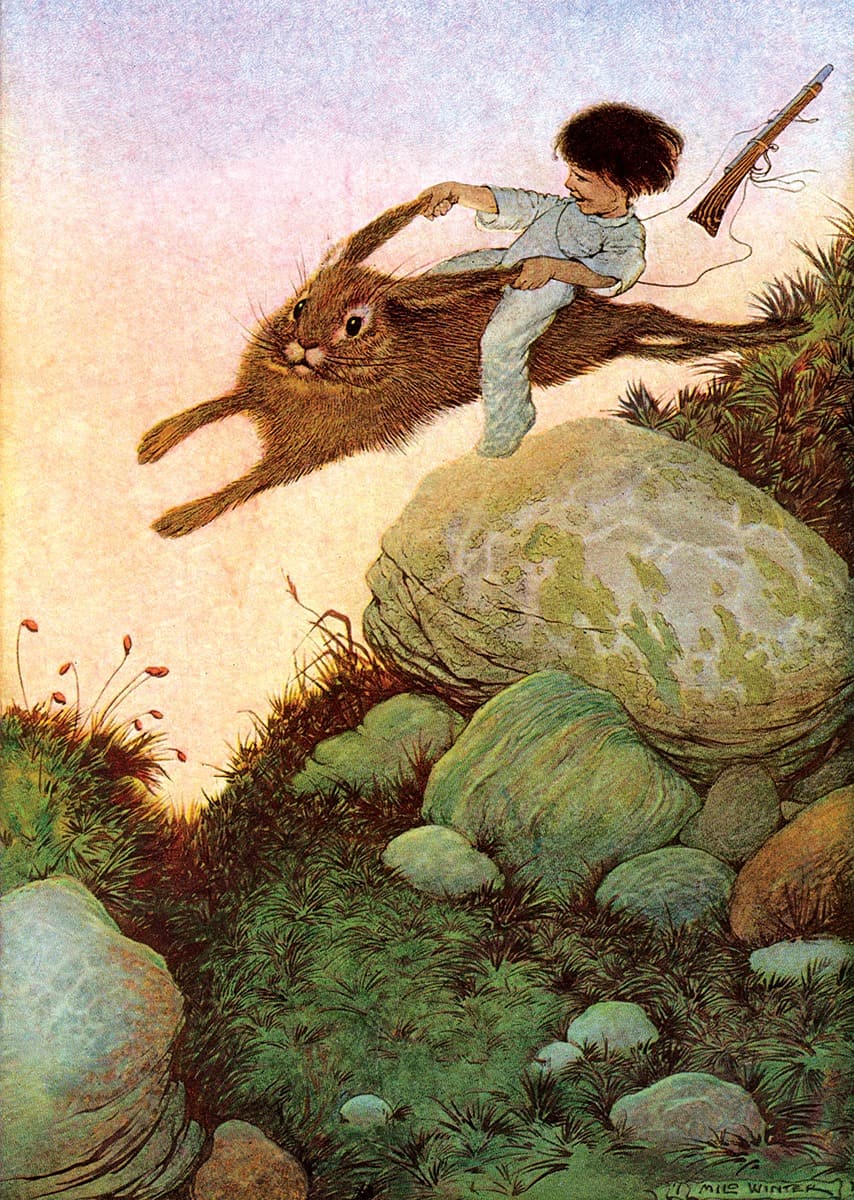

Header painting: Milo Winter (1888 – 1956), because I saw this work of art described as ‘ultimate whimsy’.