“Which Is More Than I Can Say About Some People” is a mother-and-daughter road trip short story by American writer Lorrie Moore. This story was published in The New Yorker in November 1993. Also find it in Birds of America (1999) and The Collected Stories.

The title of this story comes from something the mother of this story is known to say often. This is the sort of thing that can sound affirming, but also passive-aggressive. (“By some people, do you mean me??”)

“Theda’s, of course, sweet as ever,” said her mother, “which is more than I can say about some people.”

Perhaps the daughter, Abby, has heard this her whole life, and this is partly why she is on a self-improvement journey.

The word ‘journey’ to describe a psychological path is much reviled, and I wonder if that’s partly because it’s a word mainly utilised by women. In any case, Abby goes on an actual journey (to Irish) hoping for a psychological journey, or, in the case of a fictional character, a character arc. The raison d’être of all road trip stories. Does she get one, though?

Well, yeah, kinda. But not the kind she was after. This story is about self-help spiritual journeys, subverted. When we embark upon self-improvement, sometimes we’re in for a shock. It’s about the futility of (too-)easily getting there and then going, now what? Is this all it’s cracked up to be? The Blarney Stone pilgrimage is an excellent example of the futility of tourist life, because we can pretend to ourselves that we’re visiting it for a reason. Of course the Blarney Stone does nothing for us. (I’m tempted to say pilgrimages are historically more meaningful because of the religious aspect, but then I learned that even in the middle ages, rich people would pay poor people to do their pilgrimages for them, suggesting they were never all that meaningful for the masses.)

Sometimes in satirical stories, characters themselves almost feel they’re a character in thier own story. This is a version of metafiction. Abby sees ‘storybook symbolism’ in her own experience of being a tourist:

Abby felt sick from the flight, and sitting on what should be the driver’s side but without a steering wheel suddenly seemed emblematic of something.

Later, Abby takes note of the ‘deadly maternal metaphor’ in the Celtic curlicues.

SETTING OF “WHICH IS MORE THAN I CAN SAY ABOUT SOME PEOPLE”

In this story, an American mother and daughter take a trip through Ireland. I’ve taken a similar trip myself, but instead of driving I booked a spot on a bus tour, and instead of travelling with my mother I was ‘on my own’. But there were a few mother/child combos on that same bus, sitting behind me, sitting adjacent (one from Wollongong, another from a small town on the Australian West coast which I can’t remember the name of because it’s not Perth).

When travelling as an adult with your mother it’s easy to slip into the role of ‘child’. People are different with their mothers.

I’m a child again, Abby thought. And just as when she was a child, she suddenly had to go to the bathroom.

One of the mothers on my Ireland bus tour had prepared a bunch of snacks. “Don’t eat all the chips!” said the adult-daughter to her adult brother. “They’re not all for you, you know!” People eat more than their fair share of snacks all the time but, stuck in close quarter with this threesome over the course of days, it stood out to me that the parent-child combos were behaving differently from everyone else. Put any of us in that bus without parents, and we’d behave differently, too.

- PERIOD — contemporary (1990s?)

- DURATION — a story’s length through time. Maybe it takes place over a year, cycling through each season. Maybe it takes place over 24 hours.

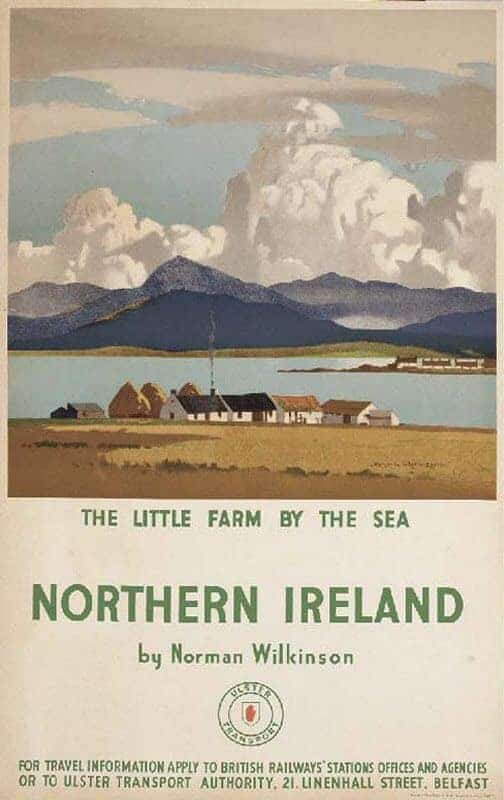

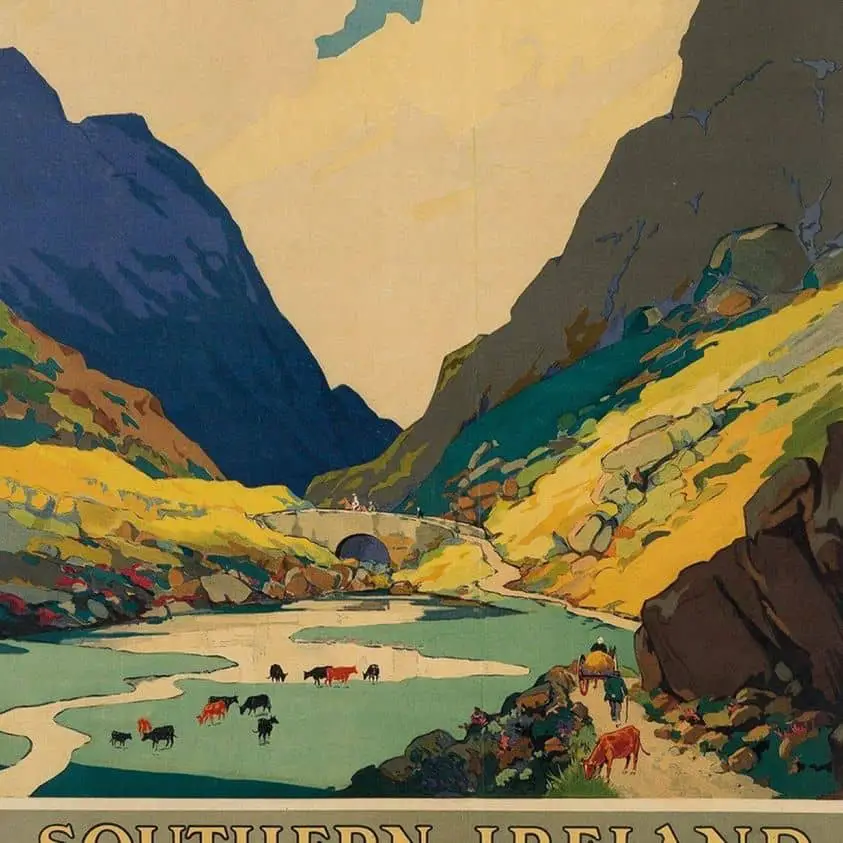

- LOCATION — Starts off in the American Midwest, jumps to the tourist route of Ireland. The American self-help culture travels with our main character to Ireland.

- ARENA — Both sides of the Atlantic

- MANMADE SPACES — Much of the action takes place inside: inside the rental car, inside the rented rooms. Is the Blarney Stone a natural object or a manmade space? Before I visited it myself, I had a completely different imaginative picture of what the Blarney Stone would be: I imagined a rocky outcrop on a beautiful coast. People who visited told me “it was actually pretty scary because you have to get right down and under it” but I hadn’t absorbed the part of the story which says you first walk through a gift shop and then line up at what looks, apart from the orderly line and the old man up top, primary school play equipment. The Blarney Stone is definitely a manmade space.

- NATURAL SETTINGS — Ireland is richly packed with rivers, mountains, forests and beaches, though in this particular story I don’t see geographical ‘fairytale’ symbolism utilised. It soon becomes clear why this is. Moore is subverting the reader expectation that something big and revelatory will happen on this journey, so her landmarks, often symbolic to people on (successful psychological) journeys, are deliberately devoid of deeper meaning.

“What is it with you?” complained her mother. From there, they visited a neolithic passage grave, its floor plan like a birth in reverse, its narrow stone corridor spilling into a high, round room. They took off their sunglasses and studied the Celtic curlicues. “Older than the pyramids,” announced the guide, though he failed to address its most important feature, Abby felt: its deadly maternal metaphor.

Abby does enter the woods (the symbolic subconscious) but it’s only in her memory (not in Ireland) and she goes in there for a comically pedestrian reason, ending in disappointment. Abby’s childhood venture into the woods ends in nothing rather than something:

On one of the family road trips thirty years ago, when she and Theda had had to go to the bathroom, their father had stopped the car and told them to “go to the bathroom in the woods.” They had wandered through the woods for twenty minutes, looking for the bathroom, before they came back out to tell him that they hadn’t been able to find it. Her father had looked perplexed, then amused, and then angry — his usual pattern.

This passage is followed by one that takes us into the present story. Abby, in Ireland, has to go back to the car to retrieve the guidebook — exactly the same sort of mundane detail that downgrade spiritual pilgrimages into logistical exercises of ‘one damn thing after the other’.

Later, Abby looks for significance in the mountains, as we are inclined to do on spiritual journeys. But when she says “Wasn’t that the truth?” has she really happened upon something signficant? (The truth about what?) Is this truth so ineffable that it’s unable to be articulated? This is almost a spoof on depth of experience and spirituality:

There was silence again between them now as the countryside once more unfolded its quilt of greens, the old roads triggering memories as if this were a land she had traveled long ago, its mix of luck and unluck like her own past; it seemed stuck in time, like a daydream or a book. Up close the mountains were craggy, scabby with rock and green, like a buck’s antlers trying to lose their fuzz. But distance filled the gaps with moss. Wasn’t that the truth?

This ineffability, or rather, the spoof thereof, can be seen elsewhere:

They ate a late supper of toddies and a soda bread their hostess called “Curranty Dick.”

“Don’t I know it,” said Mrs. Mallon. Which depressed Abby, like a tacky fixture in a room, and so she excused herself and went upstairs, to bed.

(What does Mrs Mallon ‘know’ when she hears the name of the bread? Like the opening impossible cloze exercise, the reader will never know. This is a character inside her own thought-loops, although Abby seems to get the gist, as she knows the statement is at least a sad one.)

- WEATHER — I understand Abby and Mrs Mallon are visiting Ireland at a pleasant time of year. Weather is no great impediment. Still, the weather is too useful not to mention, as a storyteller: “Out the window, there was a breeze, but she couldn’t hear the faintest rustle of it. She could only see it silently moving the dangling branches of the sun-sequined spruce, just slightly, like objects hanging from a rearview mirror in someone else’s car.” The weather grows a bit more challenging as the trip itself grows more challenging: “Rain mizzled the windshield.” When Mrs Mallon is on the rope bridge, the wind starts to gust.

- TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — The rental car system, whereby tourists can drive from place to place, take a look, move on easily — the drama of this road trip story is not the difficulty in reaching a destination. I do remember when manual transmissions were significantly cheaper (to buy and to rent) than automatic transmissions, though that gap is no longer there. Automatic vehicles have improved a lot.

- LEVEL OF CONFLICT — The Wikipedia article on “The Troubles” is divided up by decade. It was in 1991 that the IRA attempted to assassinate prime minister John Major. The rest of the decade is marked by attempted ceasefires and bombings and murders. As for these American tourists, America is in the full-throes of ‘Self-Improvement’ culture. I also remember 1990s bookstores in New Zealand (this was an Anglo-sphere thing, at least) with shelves and shelves of self-improvement books which extended into the ‘diet’ section, of course, with the cholesterol lowering, fruit-eating trends. American publishing was about to enter the age of the ‘yoga memoir’:

It was with joy/frustration/hilarity that I read, then, Judith Warner’s piece in the New York Times about the rise of the yoga memoir. And how it ties into the death of feminist political action, because all anyone wants to do anymore is “find themselves.” These days that means in the yoga studio, in the bedroom, in their home, rather than in their community, their job, their consciousness raising group. I read a list yesterday of the whatever 11 resolutions all women need to make for 2011, and of course it was nurture your soul, find time for yourself, not let’s go out and rally for real political change, or let’s protest our banks’ behavior by taking our money out, or let’s establish a community garden so that we make sure our children, regardless of financial situation, are getting nutritious, fresh food. No, let’s light a scented candle and talk to our inner child.

Bookslut

Fast forward to 2020 and the bookshelves are still full of self-improvement titles, except the reading public has grown weary and wary of ‘self-improvement’ as a genre, so now we have titles such as The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck by Mark Manson.

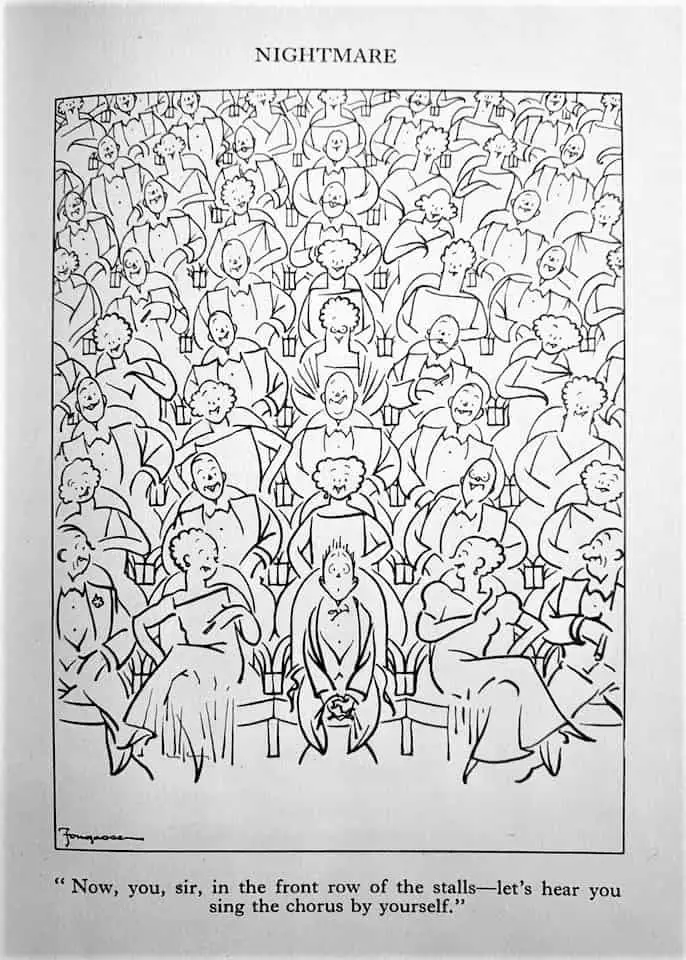

- THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — The main character feels ill-equipped for her promotion at work because it will require public speaking, so with the leave she is granted between positions she decides to kiss the Blarney Stone, fabled to give everyone who kisses it the gift of the gab. She is mistaken because she thinks this will help. She probably doesn’t really believe in the magic of the Blarney Stone, but is hoping for some kind of placebo effect.

CHARACTERS OF WHICH IS MORE THAN I CAN SAY ABOUT SOME PEOPLE

Abby Mallon

Has a job at American Scholastic Tests. We know from the first paragraph that she is one of life’s eccentrics: Lorrie Moores sets this up so deftly. Part of Abby’s job is making cloze exercises. We’re given two examples. The first is sort of solvable. The second is definitely not, showing us that Abby is on her very own wavelength.

We are not surprised, then, when Abby’s boss gives her a different role at work. We see what Abby possibly does not; not that she has become ‘too good’ at her work, but that she isn’t doing a good job at all.

It seems Lorrie Moore experiences at least a little fear of public speaking herself:

When The Paris Review approached Lorrie Moore about doing aWriters at Work interview, she responded with a warning (“My life is impossible to make interesting—others have tried before”) and a lament (“Alas, I am virtually incoherent speaking in person”). She then proposed that we simply begin with a written interview rather than “making our way politely toward one.” We compromised on an initial interview session to be followed by extensive questions and answers exchanged via U.S. mail and fax (but not e-mail, which she abjures). Of course, Moore turned out to be exquisitely coherent in person.

The Paris Review

ABBY’S MOTHER

The first line of dialogue we hear out of Mrs Mallon is “Oh, those,” after Abby confides that she’ll be required to deal with people (which the mother mishears as ‘peepers’, perhaps a comment on gossipers and the human tendency to be (overly) interested in other people’s business). Perhaps the mother is of similar disposition to Abby. We’re about to find out how the pair are alike and dissimilar. In a nutshell, Abby responds to situations with anxiety; Mrs Mallon brushes everything away. Mrs Mallon is blessed with the gift of not seeing what she doesn’t want to see.

And so they crossed the border into the North, past the flak-jacketed soldiers patrolling the neighborhoods and barbed wire of Newry, young men holding automatic weapons and walking backward, block after block, their partners across the street, walking forward, on the watch. Helicopters flapped above. “This is a little scary,” said Abby.

“It’s all show,” said Mrs. Mallon breezily.

How her mother became part of the trip, Abby still couldn’t exactly recall. It had something to do with a stick shift: how Abby had never learned to drive one. “In my day and age,” said her mother, “everyone learned. We all learned. Women had skills. They knew how to cook and sew. Now women have no skills.”

A wonderful example of Moore’s sense of humour, which I can relate to hugely, being the offspring of a self-identifying Scottish person and a self-identifying Irish person (despite also being a fifth generation New Zealand Pākehā):

“I’d like to see Ireland while I can. Your father, when he was alive, never wanted to. I’m Irish, you know.”

“I know. One-sixteenth.”

“That’s right. Of course, your father was Scottish, which is a totally different thing.”

Abby sighed. “It seems to me that Japanese would be a totally different thing.”

“Japanese?” hooted her mother. “Japanese is close.”

Mrs Mallon works at a flashlight company, which is of course metaphorical, and not at all subtle. Mrs Mallon is probably one of those people in life who thinks she’s doing you a great favour by volunteering (unbidden) her character sketch of you. At least, she does that to Abby, using her own self as yard stick rather than any professional psychological tools, of course, but with a ‘sort of pseudo-wisdom she donned now that she was sixty’:

“You scare too easily,” said her mother. “You always did. When you were a child, you wouldn’t go into a house unless you were reassured there were no balloons in it.”

When Abby experiences anxiety before kissing the stone, her mother tells her not to be a “ninny”.

Via Abby’s focalisation we learn that Mrs Mallon is “strong as a brick” but with a “sigh of death.”

Along their journey, mother and daughter will meet a variety of characters, some ‘mentor’ archetypes, some ‘foes’. Unlike your classic Oedipus story, a lot of these ‘people they meet along the way’ are in fact memories of characters that bubble up (largely unbidden) because time in the car with her mother is giving Abby time to think. This road trip could be taking place anywhere (except for the useful addition of The Blarney Stone).

Mrs Mallon is a bit of a Mr Magoo comedic archetype, someone who flings themselves wildly about and doesn’t seem to understand they can’t see well:

Her mother lurched out of the parking lot and headed for the nearest roundabout, crossing into the other lane only twice. “I’ll get the hang of this,” she said. She pushed her glasses farther up on her nose and Abby could see for the first time that her mother’s eyes were milky with age. Her steering was jerky and her foot jumped around on the floor, trying to find the clutch. Perhaps this had been a mistake.

In fiction, when characters have a visual impairment, this is often emblamatic for an inability to see other things in their lives (abstract things), though it’s the fact she doesn’t know she can’t see very well that’s key.

BOB

Abby’s ‘ghost‘, though even then, he’s subverted because he doesn’t seem to have any emotional hold on Abby in the present, precisely because he didn’t mean much to her even when they were together. Former husband. Bob feels like a generic ‘everyman’ name and we don’t learn much about him other than Abby’s attitude towards him — she makes it sound like when she was on the prowl for a husband, any old man would do. Descriptions like these lead me to the belief that Lorrie Moore often writes about (what she never names as) the Split Attraction Model ( a word from the queer community which cishet allos can also find useful).

Of all Abby’s fanciful ideas for self-improvement (the inspirational video, the breathing exercises, the hypnosis class), the Blarney Stone, with its whoring barter of eloquence for love — O GIFT OF GAB, read the T-shirts — was perhaps the most extreme. Perhaps. There had been, after all, her marriage to Bob, her boyfriend of many years, after her dog, Randolph, had died of kidney failure and marriage to Bob seemed the only way to overcome her grief. Of course, she had always admired the idea of marriage, the citizenship and public speech of it, the innocence rebestowed, and Bob was big and comforting. But he didn’t have a lot to say. He was not a verbal man. Rage gave him syntax — but it just wasn’t enough! Soon Abby had begun to keep him as a kind of pet, while she quietly looked for distractions of depth and consequence.

THE POET

This description of Abby’s flaneur-type love interest reminds me of the sort of man Katherine Mansfield liked to write about (e.g. the main character of “Je ne parle pas francais”).

She looked for words. She looked for ways with words. She worked hard to befriend a lyricist from New York — a tepid, fair-haired, violet-eyed bachelor — she and most of the doctors’ wives and arts administartors in town. He was newly arrived, owned no car, and wore the same tan blazer every day. “Water, water everywhere but not a drop to drink,” said the bachelor lyricist once, listening wanly to the female chirp of his phone messages. In his aparmtne, there were no novels or bookcases. There was one chair, as well as a large television set, the phone machine, a rhyming dictionary continuously renewed from the library, and a coffee table. Women brought him meals, professional introductions, jingle commissions, and cash grants. In return, he brought them small piebald stones from the beach, or a pretty weed from the park. He would stand behind the coffee table and recite his own songs, then step back and wait fearfully to be seduced. To be lunged at and devoured by the female form was, he believed, something akin to applause. Sometimes he would produce a rented lute and say, “Here, I’ve just composed a melody to go with my Creation verse. Sing along with me.”

THEDA

Abby’s sister. Theda has Down’s Syndrome and, like their mother, has her own oft-repeated phrase, strongly associated with her. “Look at you!” she exclaims. (My take is that she would’ve learned this from the mother.)

STORY STRUCTURE OF WHICH IS MORE THAN I CAN SAY ABOUT SOME PEOPLE

SHORTCOMING

Abby is terrified of public speaking but her new role at work will require it of her. (My read is that the supervisor knows this and is trying to push her out of the company rather than go through the paperwork and discomfort of firing her.)

She’s been avoiding people for so many years that she is no longer even thinking in the same way as most. This line reminds me of the character of Dame Slapalot in one of Enid Blyton’s Faraway Tree books — a teacher who asks impossible questions and then punishes her students for failing to answer them. In this story:

blank is to heartache as forest is to bench.

Abby has a pedantic streak, and is a linguistic prescriptivist:

She missed the plentiful U-Pump-Itt’s, where, she often said, at least they spelled pump right!

DESIRE

Abby is a quiet, passive character who wants to continue doing her quiet job which does not involve working with people.

Abby’s character arc in Ireland will take her from an upbeat place to a downbeat place. Here’s how she feels about the Irish countryside when first experiencing it. A classic tourist’s view, through rose-tinted glasses, though that final touch takes us back to a grimmer reality:

The Irish countryside opened up before them, its pastoral patchwork and stone walls and its chimney aroma of turf fires like some other century, its small stands of trees, abutting fields populated with wildflowers and sheep dung and cut sod and cows with ear tags, beautiful as women. Perhaps fairy folk lived in the trees! Abby saw immediately that to live amid the magic feel of this place would be necessarily to believe in magic. To live here would make you superstitious, warm-hearted with secrets, unrealistic. If you were literal, or practical, you would have to move — or you would have to drink.

OPPONENT

The first opponent is the unnamed, ungendered supervisor who gives Abby a new role at work.

Next, as mother and daughter travel round Ireland in a car, Abby’s opponent will be her own mother.

PLAN

Moore summarises a few self-help things Abby has done. Next, Abby decides to travel to Ireland to kiss the Blarney stone. Perhaps this will help her somehow. (We don’t know if she actually believes in its magic.)

THE BIG STRUGGLE

In the car with her mother through Ireland, Abby comes face to face with her child self (in relation to her mother), and is forced to deal with romantic opponents of the recent past — Bob, and the flaneur she might’ve left Bob for.

Ironically — beautifully, for this story — Abby’s depths into darkness happen in the car because she doesn’t want to get out and cross a precarious-looking bridge. The ‘near death’ experience does not happen to Abby on a rope bridge, but happens in recent memory:

Abby waited, now feeling the true loneliness of this trip. She realized she missed Bob and his warm, quiet confusion; how he sat on the rug in front of the fireplace, where her dog, Randolph, used to sit; sat there beneath the five Christmas cards they’d received and placed on the mantel — five, including the one from the paperboy — sat there picking at his feet, or naming all the fruits in his fruit salad, remarking life’s great variety! or asking what was wrong (in his own silent way), while poking endlessly at a smoldering log.

ANAGNORISIS

There are plenty of self-revelations in this short story. Here’s the thing, though: some of them are genuine, and others are false.

The revelation comes right after the visit to death. What does Abby realise, sitting in the car contemplating her dead dog and also about the ‘pale bachelor lyricist, how he had once come to see her, and how he hadn’t even placed enough pressure on the doorbell to make it ring’?

Notice the deliberately purple prose:

O poetry! When she invited him in, and he gave her the flower and sat down to decry the coded bloom and doom of all things, decry as well his own unearned deathlessness, how everything hurtles toward oblivion, except words, which assemble themselves in time like molecules in space, for God was an act — an act! — of language, it hadn’t seemed silly to her, not really, at least not that silly.

This sounds like a revelation, but is entirely ironic: Abby learns nothing of use from this guy. The reader can see that the man who is so timid he doesn’t place enough pressure on a doorbell to make it ring is basically the male equivalent of anxiety-ridden Abby, hiding from people, hiding from life.

Thinking of her mother on the rope bridge, she has a useful, concretised revelation:

Abby knew from AST that a surprising percentage of those taking the college entrance exams never actually applied to college. People just loved a test. Wasn’t that true? People loved to put themselves to one.

Now the reader understands (if we haven’t already) that Abby also loves a test. That’s precisely why she’s come to Ireland. However, Abby does not turn that insight back on herself. She doesn’t feel that she, herself, loves a test.

This is followed by yet another self-revelation from Abby, but note that this could be said of any fictional character embarking upon any Odyssean mythic journey:

Abby began to think that all the beauty and ugliness and turbulence one found scattered through nature, one could also find in people themselves, all collected there, all together in a single place. No matter what terror or loveliness the earth could produce — winds, seas — a person could produce the same, lived with the same, lived with all that mixed-up nature swirling inside, every bit. There was nothing as complex in the world — no flower or stone — as a single hello from a human being.

The non-reflective Mrs Mallon eventually does a bit of self-reflecting:

“I never had a real childhood,” she said, taking the bag and looking off into the middle distance. “Being the oldest, I was always my mother’s confidante. I always had to act grown-up and responsible. Which wasn’t my natural nature.” Abby steered her toward the door. “And then when I really was grown up, there was Theda, who needed all my time, and your father of course, with his demands. But then there was you. You I liked. You I could leave alone.”

This time, it’s Abby’s turn to shoot her mother down, and basically tell her she’s being too much. I get the feeling it’s payback:

“I bought you a smock,” Abby said again.

At the Blarney Stone, Abby learns something about her mother. The mother’s mask has come off:

Abby suddenly saw something she’d never seen before: her mother was terrified. For all her bullying and bravado, her mother was proceeding, and proceeding badly, through a great storm of terror in her brain. As her mother tried to inch herself back toward the stone, Abby, now privy to her bare face, saw that this fierce bonfire of a woman had gone twitchy and melancholic — it was a ruse, all her formidable display.

Now the reader understands that although mother and daughter were presented as opposites (anxious vs brave), both women are anxious types. They simply deal with in different ways. As it happens, Abby’s refusal to put her head in the sand may be the more adaptive model. She has been able to kiss the stone without panicking, precisely because she’s acknowledged her fears beforehand.

This difference between mother and daughter says something more broadly about the generations, I feel. This difference was highlighted in discussions around the recent #metoo movement. To generalise, of course:

Younger women: This is not okay. The culture needs to change. We shouldn’t have to put up with this silently anymore.

Older women: I had to put up with it, we all did, get over it. It’s really not so bad and we’ve come a long way.

Now that the mother’s mask has come off, with the further plot revelation that the mother panicked on the rope bridge, Abby is more gentle towards her mother:

It was really the world that was one’s brutal mother, the one that nursed and neglected you, and your own mother was only your sibling in that world.

She looks down at sees ‘a cartoon of a big-chested colleen, two shamrocks over her breasts.’ The big-chested colleen is a grotesque representation of womanhood, breasts standing in for maternity. Abby has been seeing her own mother as a groteque representation of womanhood. We saw this earlier in the memory of accidentally barging in on her mother in the toilet (which may not have been her mother, which means mother equals womanhood more universally). I initially wondered about the purpose of that scene of the mother in the toilet and now I see the symbolic significance of it — a classic example of delayed decoding.

What do you think of the epiphanies of this story? Some critics find the insights ‘overblown’:

[Moore’s] dialogue is often jarringly cute and she loads even a strong last page (‘Which Is More’) with impossibly overblown insights: ‘It was really the world that was one’s brutal mother, the one that nursed and neglected you, and your own mother was only your sibling in that world.’

Adam Mars-Jones, The Guardian

NEW SITUATION

The story ends with a beautiful moment between mother and daughter. Playing a role as they drink together in an Irish pub, Abby ‘courts’ her mother, who ‘has never been courted before’.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

The emotional valence of this story has gone from downbeat (job upheaval) to upbeat (enjoying tourist life) to downbeat (terrified by tourist life, because it reminds Abby of her public speaking weakness) and finally elicits a heartwarming feeling as a mother and daughter understand each other a little better than before.

Will this moment last? I suspect this mother-daughter relationship has been altered forever, though this won’t play out in their daily interactions with each other in a major noticeable way to outsiders. These minor revelations rarely work like that.

RESONANCE

We are in the age of the anti-journey, in which short story readers would find it difficult to accept a non-satirical story about a character who visits the Blarney Stone, kisses it, and then everything is better. Those stories belong to the age of The Miracle Story (and those were a long time ago).

For another short story example of the anti-Mythic journey, see Helen Simpson’s “Diary of an Interesting Year”, which likewise focuses on the mundane, but in a dystopian setting.

An Irish story (by an Irish writer, actually set in Wales) which reminds me of this one: Beer Trip to Llandudno by Kevin Barry. The humour, the reason for the trip, the darkly humorous character sketches and the inversion of a beautiful self-revelation are all mirrored in Barry’s story.