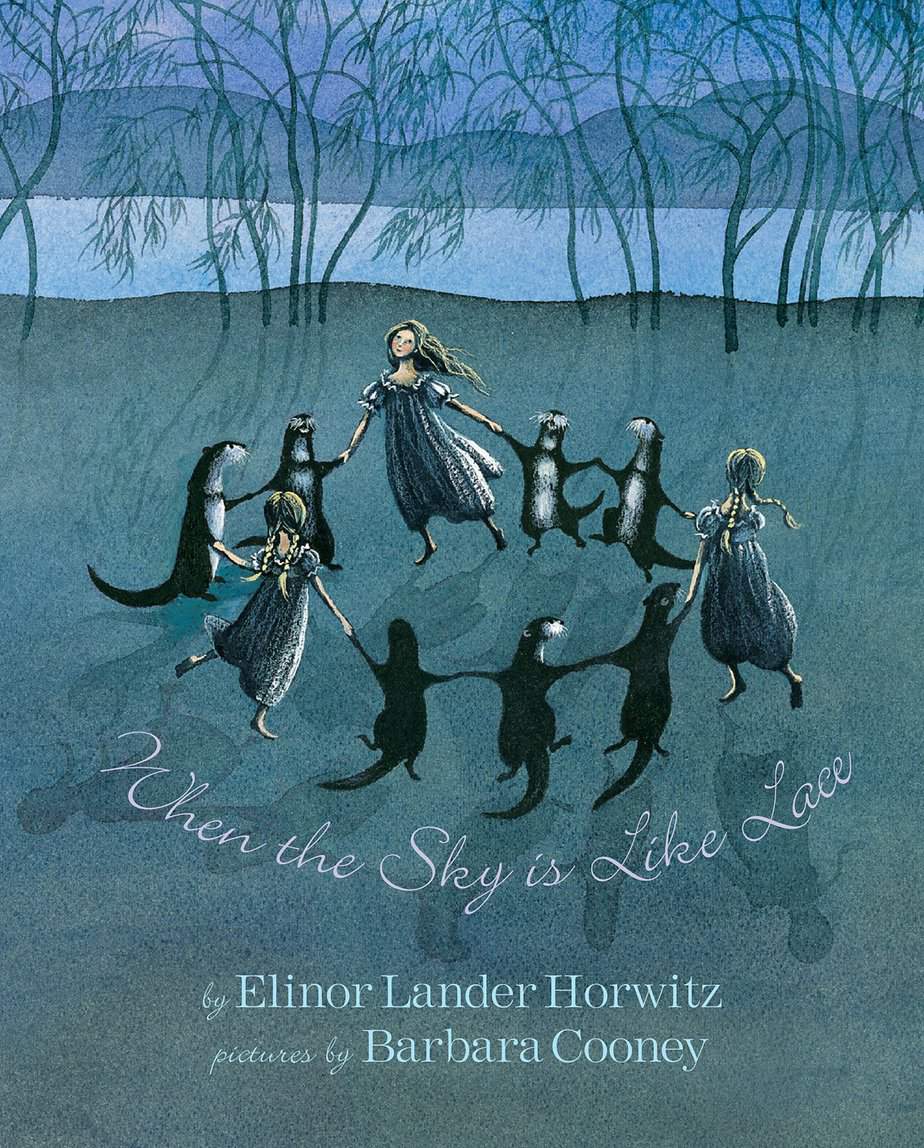

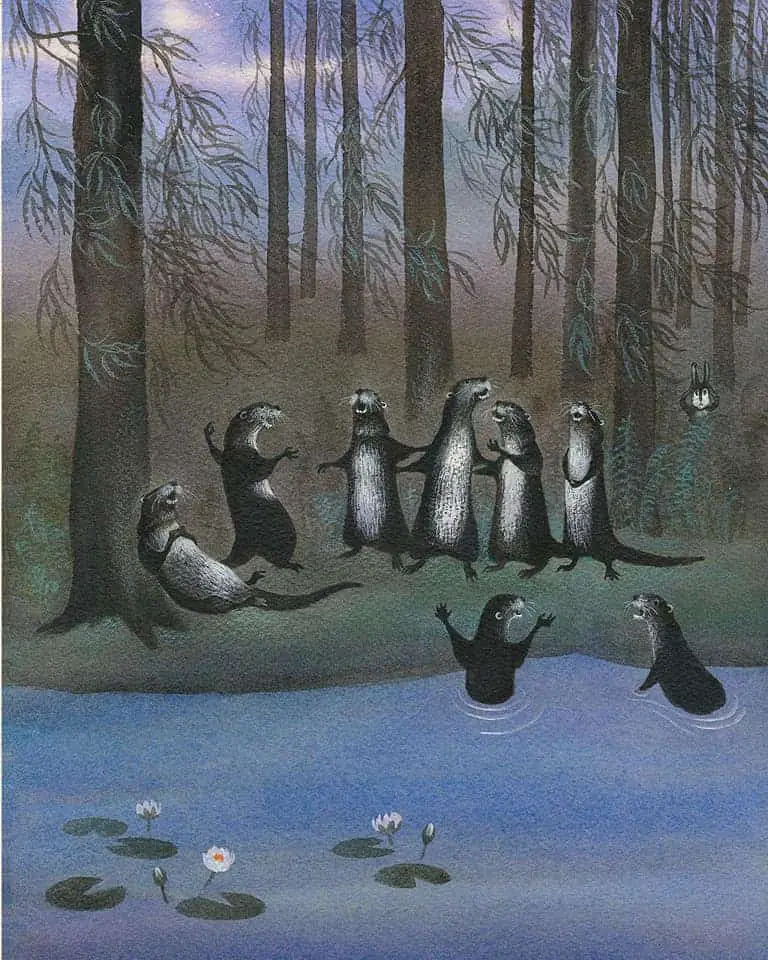

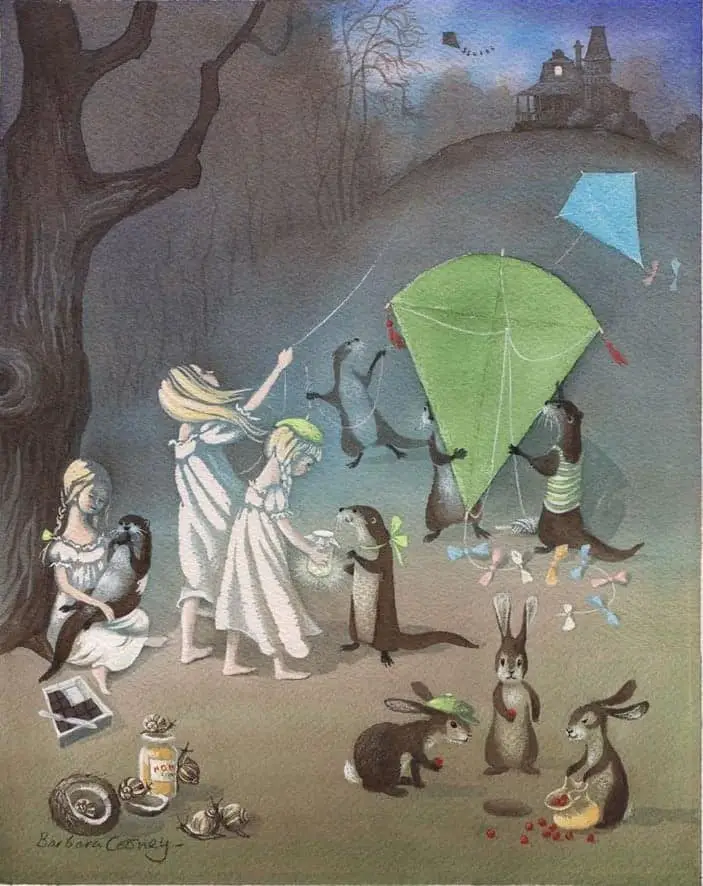

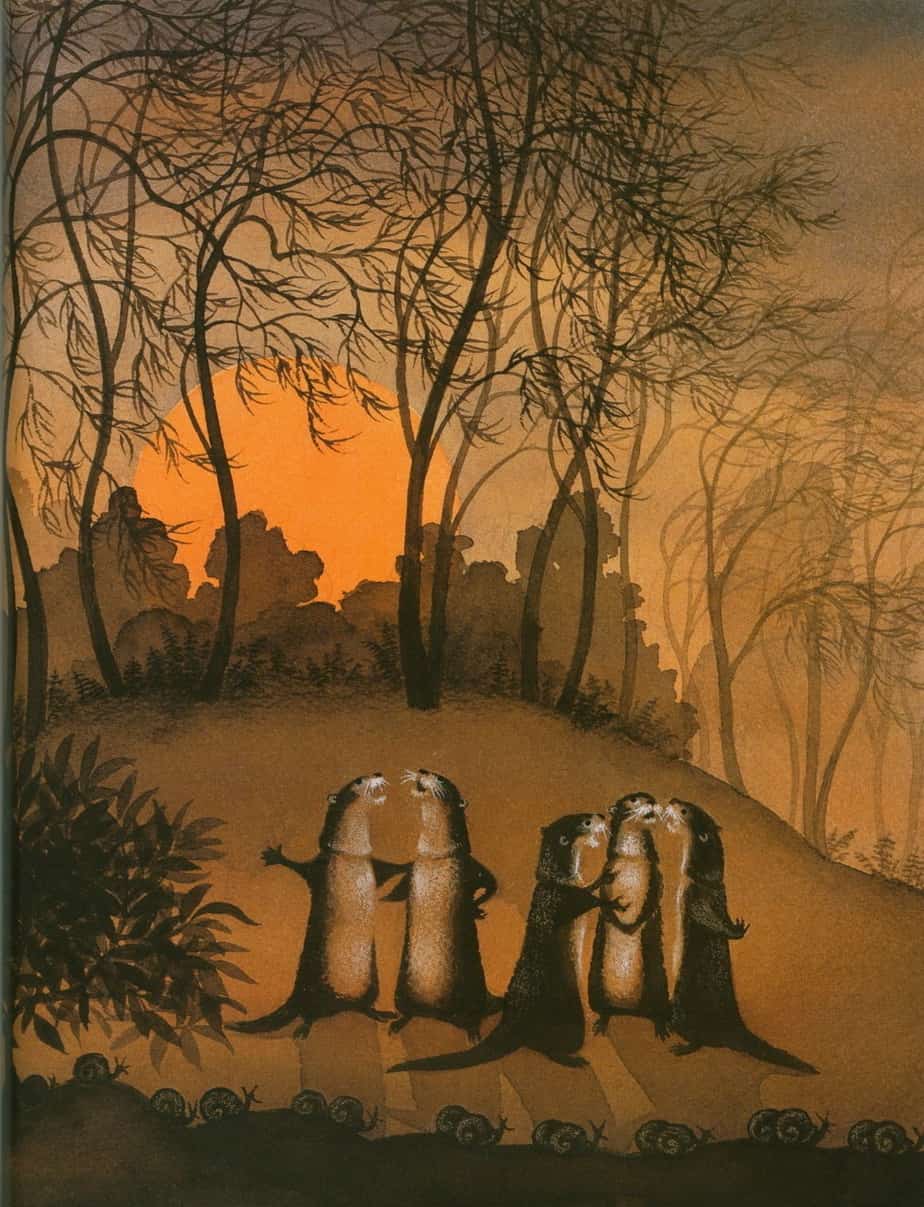

When The Sky Is Like Lace (1975) is a picture book written by Elinor Lander Horwitz and illustrated by Barbara Cooney (1917-2000). If you read Wind in the Willows and wanted more otters, this one’s for you. (I’m not familiar with otters but I think these may be river otters rather than sea otters?)

Some picture book authors have the ability to tune into a childlike way of speaking. When The Sky Is Like Lace achieves that voice magnificently. For other picture book examples of childlike speech patterns, check out the work of Chris McKimmie, e.g. Good Morning, Mr Pancakes. Books like these are often described as ‘whimsical‘.

If you liked the odd words used by Beatrix Potter and also the made-up words in “The Jabberwocky” by Lewis Carroll, you’ll love the word ‘bimulous’, the leitmotif of this picture book. What does the nonce word ‘bimulous’ mean? It means whatever you want it to mean. Something magical, for sure.

And if you enjoyed reading about Kezia in Katherine Mansfield’s most famous trilogy of short stories, notably in “Prelude“, you can find a similar sort of kid in this picture book: A girl who plays spontaneously and who looks for magic in the quotidian.

Moreover, if you’ve ever wondered what fantasy witches were like as children, this picture book provides an answer. Are they witches or fairies, though? This book encourages a blurring of those boundaries. (Are contemporary fairies sanctified witches for children?)

SETTING OF WHEN THE SKY IS LIKE LACE

There’s an atemporal fairytale setting to this story. What contributes to that atmosphere?

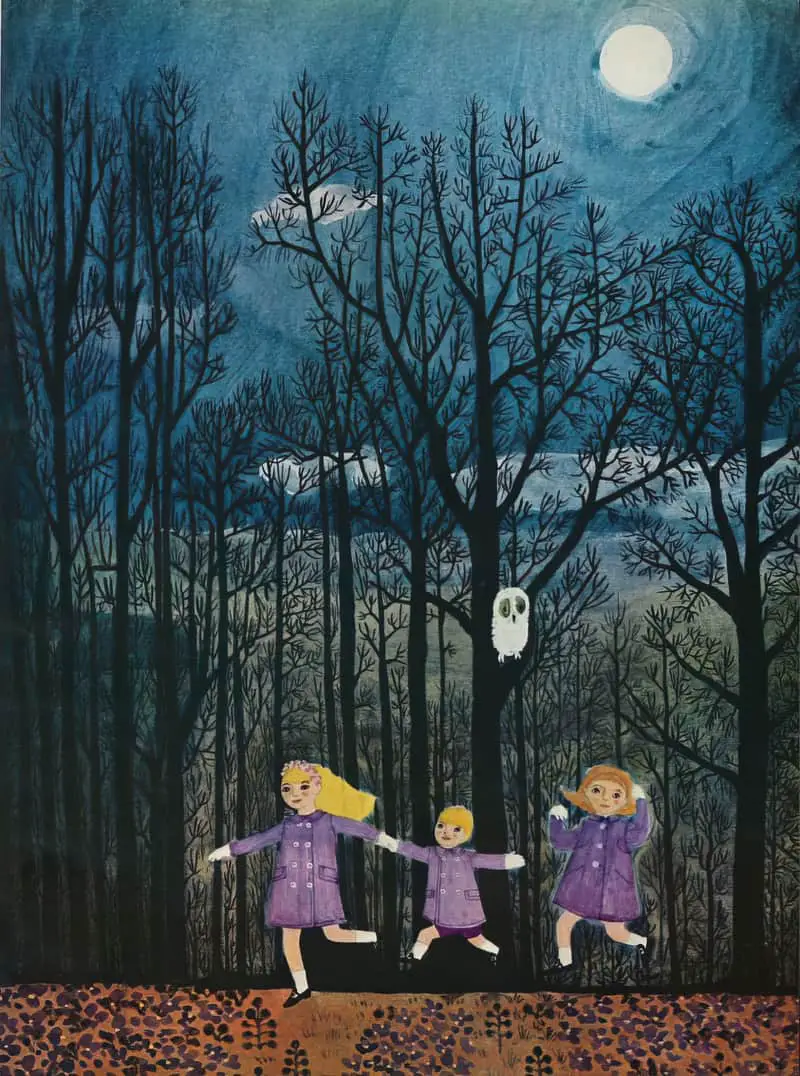

Like the Three Princesses/sisters/siblings of fairytales, this story stars three girls. (Likewise, witches tend to gad about in groups of three. Cf. Shakespeare.)

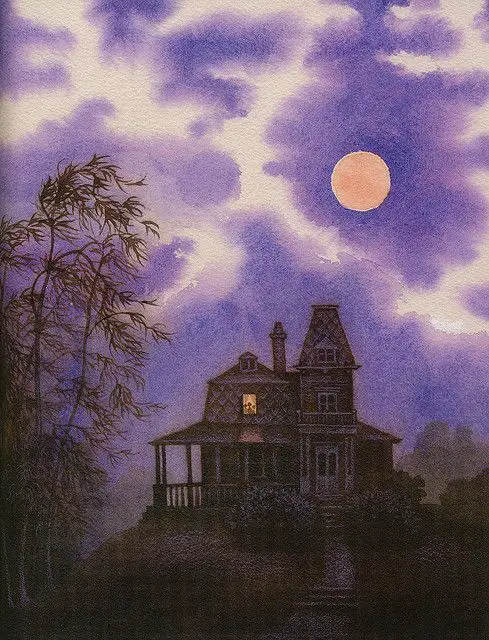

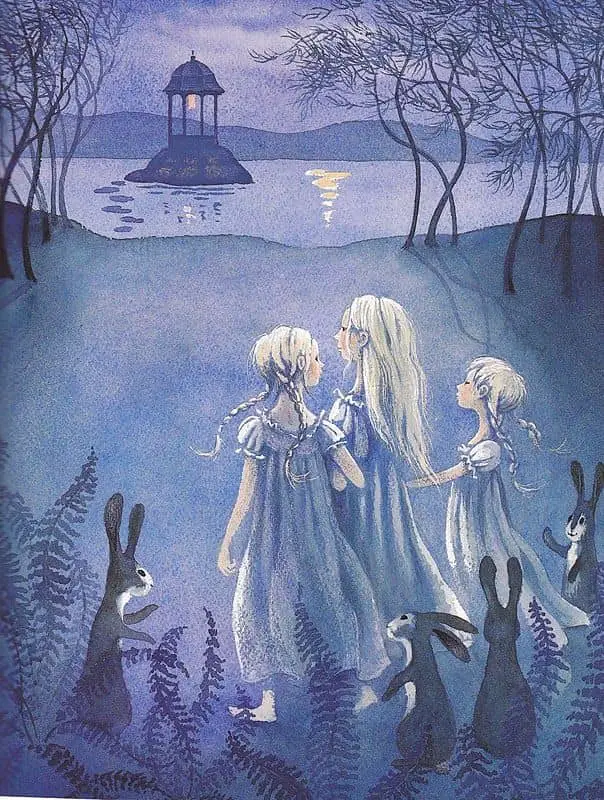

The house is a symbolic dream house and sits right next to a variety of natural features, including woods and a body of water. The night transforms the setting into someplace magical. Like many depictions of night-time in picture books, the artist, Barbara Cooney, has depicted the night scenes in high chroma. The colour of the sky changes over the course of the night.

The moon is as bright as a sun. The moon is larger than life (common in all kinds of picture books).

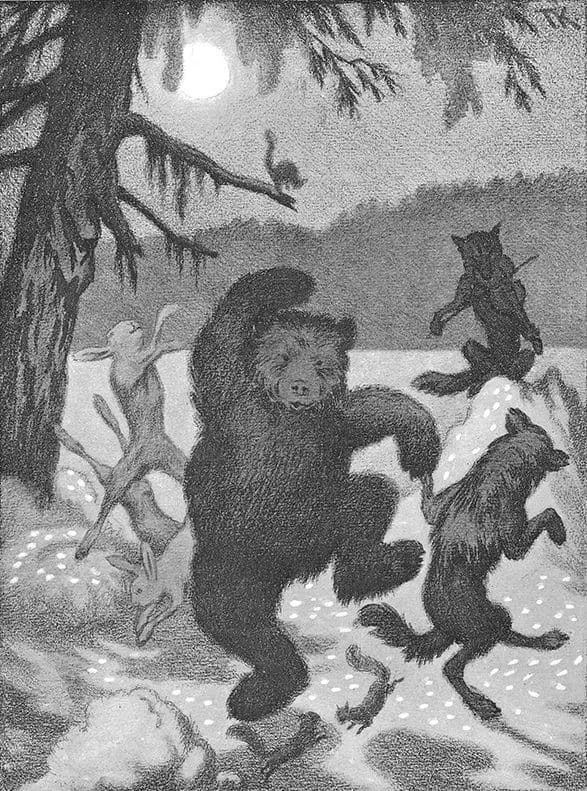

The animals become anthropomorphised as the story progresses.

Even the trees seem to dance.

The cover features characters dancing in a circle. Humans do like to hold hands in a circle. It’s a prosocial thing to do in certain situations. It’s also imbued with magic. This is how we make wishes. We feel connected to our communities and believe it has an apotropaic effect. Witches also do this, standing around in circles (9 feet in diameter).

STORY STRUCTURE OF WHEN THE SKY IS LIKE LACE

PARATEXT

What happens when it’s bimulous and the sky is like lace? Strange and splendid things! Otters sing, trees dance, and the grass is like gooseberry jam. There’s a special party that anyone can attend. Anyone, that is, who knows the rules and isn’t afraid of plum-purple shadows, can cook spaghetti and would like to teach a new song to the otters.

MARKETING COPY

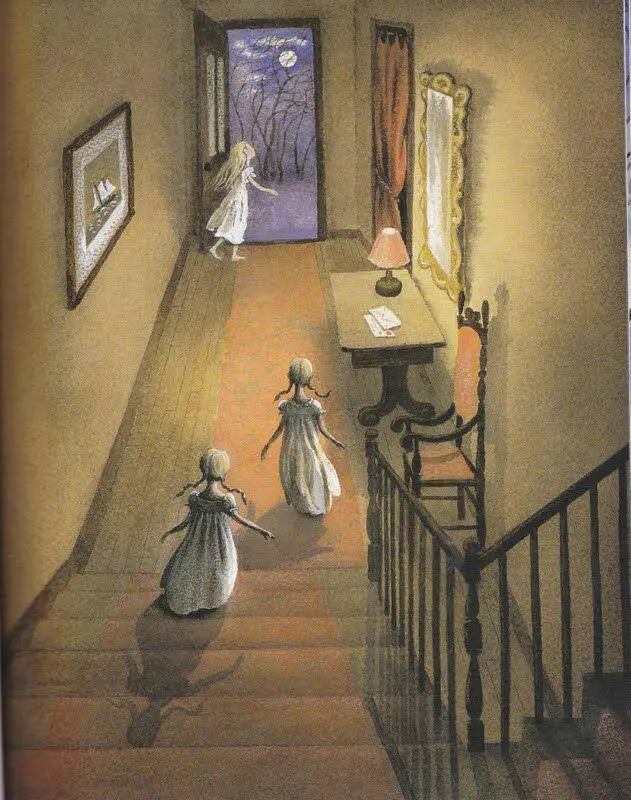

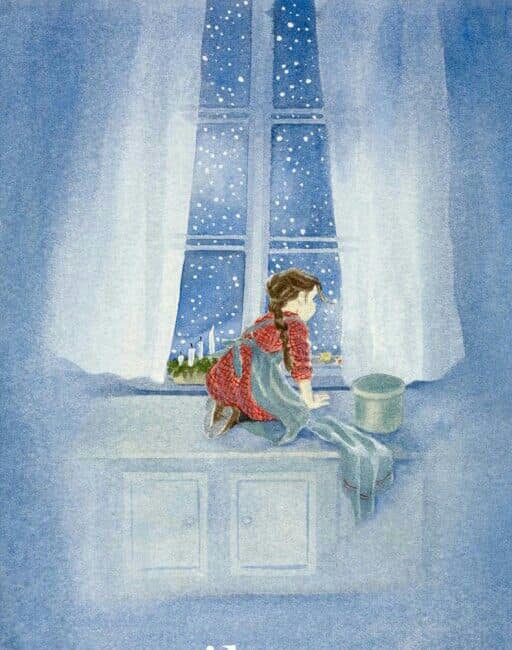

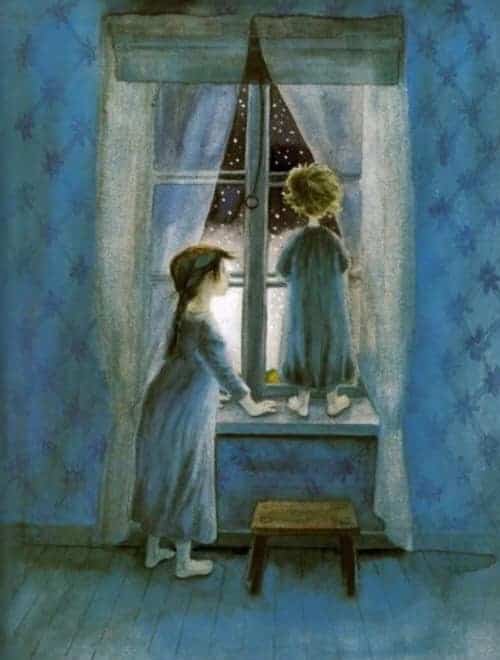

The story opens with an over-the-shoulder longshot view of three girls looking out a window. Their differing heights indicate they are sisters. They all wear the same blonde hair, the same white nightgown. Their amorphous amalgamated shadow stretches partway up the wall; we know it is night-time and that this story is going to be deliciously creepy. The wavy lines of the curtains, the pattern of the carpet, all suggest ‘lace’.

Why a back view to introduce these main characters? In many picture books, illustrators offer a static portrait so we can get a good, long look at our main character. These girls are supposed to be Every Girls. We can paste ourselves onto them if we don’t know much about them.

The next page is a long shot of the house. The girls are tiny silhouettes looking out from a second-storey window. As will be true in a number of illustrations throughout the book, the sky fills more than half of the page.

A standout feature of When The Sky Is Like Lace is the childlike lullaby language punctuated periodically by something that punches the reader out from the spell. This happens on the second page with ‘Kaboom!’ There’s a comedic quality to this; the girls have been encultured into a soft, gentle before-bedtime ritual of soft, quiet, gentle stories, yet yearn for adventure outside the house. Using the language and tradition of lullaby, the girls are creating their own excitement.

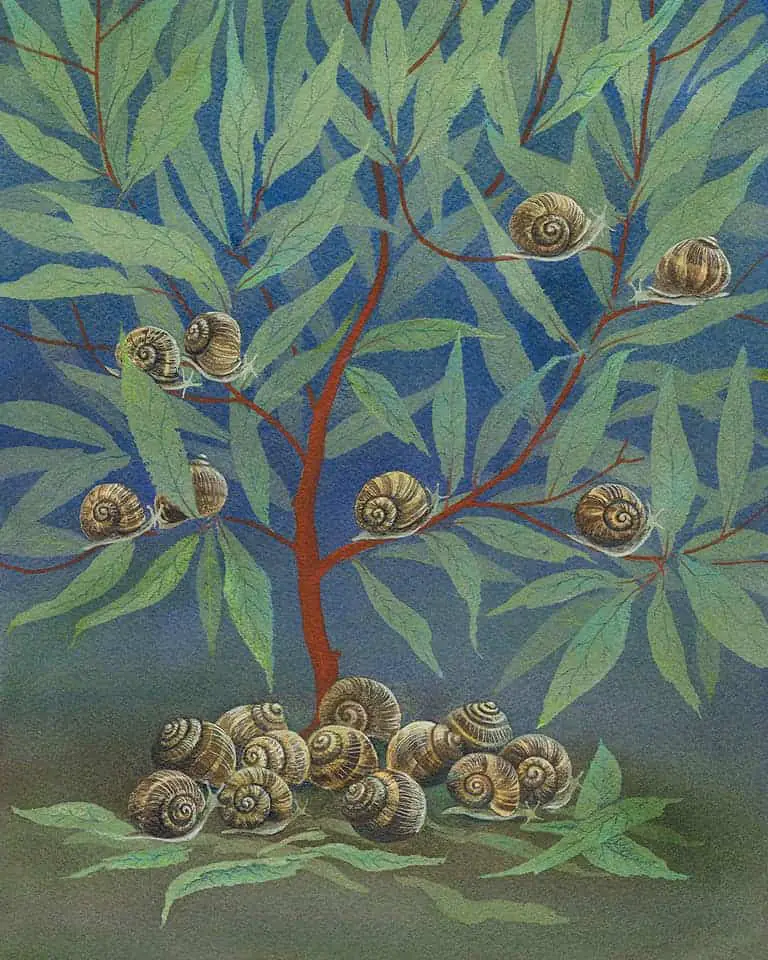

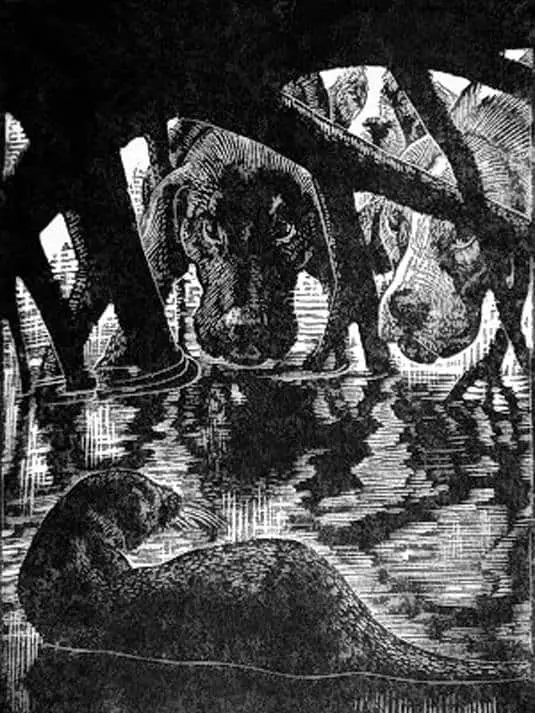

The narrative camera shifts from the three Every Girls to the otters, and then to the snails. This hypodiegetic narrative about how the otters offend snails by insisting they all look alike is precisely the sort of diversion which gets a story labelled ‘whimsical’ or ‘quirky’.

Now the story takes readers further into the carnivalesque. The girls are away from the civilisation and safety of the home, plunged into the woods where animals do human things in the night.

It’s interesting that the otters sing ‘nasty’ songs. There’s a hint of danger to these woods. The girls aren’t necessarily going to be looked after.

The otters are singing their nasty song about snails, who they say look just like each other. Children are wonderfully observant and this sequence may well encourage young readers to look more closely at snails in future.

“Couldn’t Tell Mrs From Mr”

When The Sky Is Like Lace evinces a typically mid-1970s understanding of sex, gender and… snails. For an excellent breakdown of the history of the word ‘gender’, see A Brief History of Gender at language: a feminist guide.

Picture books are full of anthropomorphised creatures. There are many storytelling reasons for this. However, sometimes anthropomorphism can tip over into, well, binarist and weird.

At this point I will clarify my own stance towards the politics of picture books: Implicit ideology is the most powerful ideology of all. Children are sponges and very smart. They’re learning machines. Therefore, picture books are some of the most powerful tools of thought-control in existence. That’s why I dedicate so much time writing about them and analysing them at a granular level.

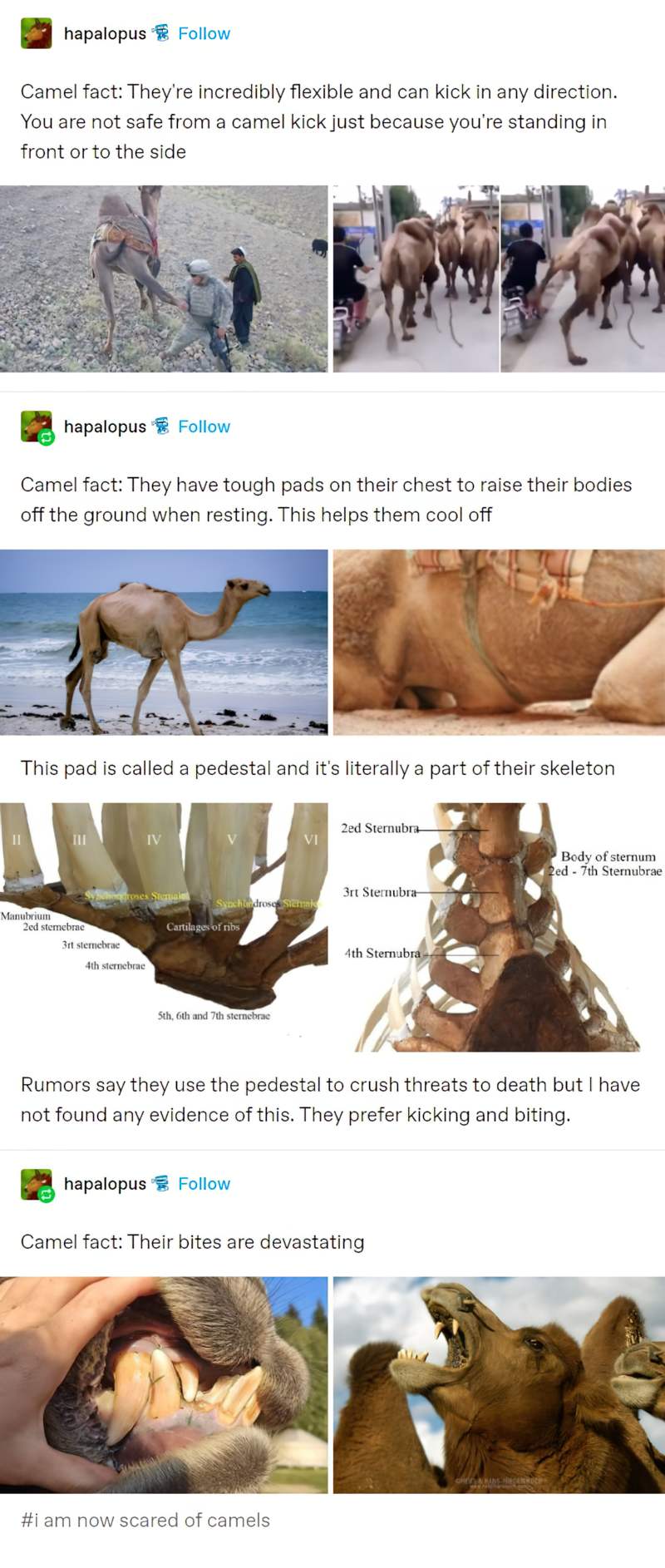

There’s a line regarding snails with comical intent. The otters can’t “tell Mrs from Mr”. This is classic example of humans pushing a human gender binary onto a creature which not only doesn’t have a gender but onto a creature frequently held up as a prime example of how human sex binary pushed onto the animal kingdom simply doesn’t work.

Snails are hermaphrodites. This means each snail can produce both sperm and eggs. The binary labels of “Mrs and Mr” could never apply to snails.

“But it’s just a story,” you might say. Well, leaving snails aside, human sex is not binary, either. Human sex is bimodal.

Sex characteristics tend to be bimodal, meaning there are clusters of characteristics that tend to be associated with people that we call “female” or “male.”

The Gender Spectrum: A Scientist Explains Why Gender Isn’t Binary

When stories for children anthropomorphise animals in this specific way, there is an implicit ideology behind it: “Gender and sex are binary, and binary is the norm all across the animal kingdom. Ergo, it’s only natural that human sex is binary, too.”

If you’ve ever encountered a binarist adult who holds up animals as ‘evidence’ for binary sex (and gender) in humans, you can safely conclude they’ve been fed a steady diet of books just like this one at a formative age.

If reading this book to a modern child, the snail example is a good opportunity to delve into the reality of snails, even if you don’t touch the concepts of ‘binary’ and ‘bimodal’. Kids need to know how snails work. This will come in very handy for them later when you’re teaching them about how trans, non-binary and intersex people exist.

The overall message about the individuality of snails in When The Sky Is Like Lace is a very good one: “Each snail believes himself to be quite different from all the other snails. Very much himself.” This ideology segues smoothly into the exact message contemporary picture books such as My Shadow Is Pink.

The Girls Leave The House

The high angle perspective from the top of the stairs suggests the reader is the fourth sibling, following behind like a ghost. This will be an exciting adventure.

Outside, the grass is “like gooseberry jam” but “not really squooshy like jam”. What wonderful use of onomatopoeia. Technically, “squooshy” is an example of mimesis rather than onomatopoeia, because rather than describing the sound jam makes, it describes the feel of it.

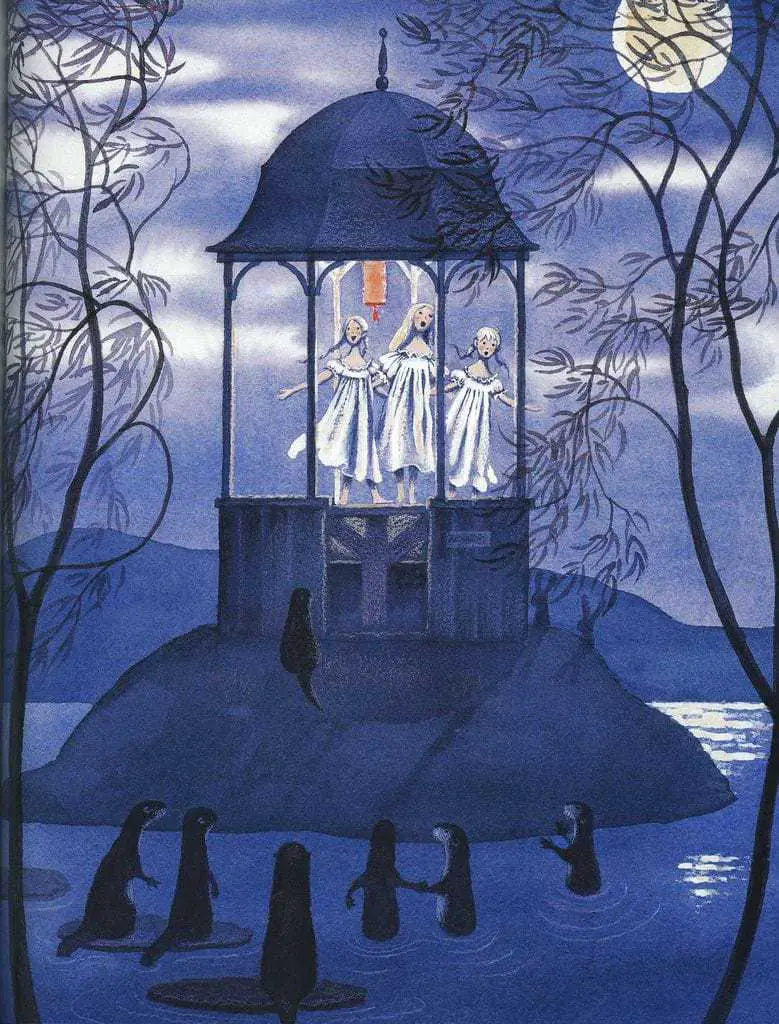

They Reach The Pagoda

Notice the four rabbits, not mentioned in the text. Each girl, plus the young reader, has a rabbit as a spirit animal.

I get the feeling the narrator of this book is the tallest of the girls. In typical older sibling fashion, she is making up the rules of the game, inviting the younger children into the magic which she possibly doesn’t fully believe herself. But she knows the younger children will buy into it wholesale. It’s a marvellous feeling to entrance a younger child in this way.

The author does a magnificent job of mimicking the ad lib rule-making children engage in during play. “If your nose itches, don’t scratch it!”

Lullaby, Jolt

However, unlike a child ad libbing the rules, there’s a cumulative effect in this story. The narrator repeats all of the rules and observations, ending with “it’s a good idea to be prepared”. This lulls the reader as a lullaby might. Then, “you never know.” Lullaby, jolt, lullaby, jolt. That’s the rhythm of the story as a whole.

“The next thing to talk about is the eating.”

Food is immensely important in children’s literature. Night journeys frequently feature a midnight feast. The otters and the rabbits don’t worry about human table manners. The otters comically eat spaghetti with pineapple sauce — a gross out touch which might actually appeal to child readers. We are in firm carnivalesque territory now, away from the authority of adults. The girls are literally on their own island, when they’re meant to be tucked up in bed at night. This is the entire plot of The Tiger Who Came To Tea.

“You’ll have to make up the tune yourself”

The title of the song is “The Katy-did” but young readers are encouraged to make up the tune. Notice how the author adeptly draws readers into the imaginative play. Even paper books can be ‘interactive’ (a word mostly used for digital books). Interactivity isn’t about the medium, it’s all in the mode of telling.

The Importance of Flight

Like food, flight is immensely important in children’s literature. Here, characters don’t literally start flying through the air. But the author takes readers into the sky via kites and mention of fireflies (which fly, and which also look magical).

A list of intriguing items follows, including a coconut — an exotic treat to many English speakers of the 1970s. The list contributes to the lullaby effect.

Now exoticised animals enter the woods: a camel, an elephant.

Animals dancing together in the woods under moonlight are a common fantasy:

Another list follows, this time a list of verbs: all the things you might like to do if you could do anything at all.

Safe Home In Bed

We don’t see how the girls get home. There’s a pacing Gap and we see the girls tucked up safely in bed. This suggests (to me, an adult reader) that the entire story took place in bed, with one of the girls spinning the other two (plus young reader) a story. Those lacy curtains are the giveaway: The sky looks like lace because she is seeing the sky through them.

But ambiguity is maintained, because this bedroom scene is actually a flashback.

Note what the author is doing: Taking young readers on an exciting journey outside the home at night, then returning them safely once the story might get a little too scary (jungle animals frolicking in the woods).

Epilogue

The structure of this picture book is unusual. After the author and illustrator show us the girls tucked safely into bed, that’s where the vast majority of picture books end. But this book now gives young readers a list of ‘rules’. This list of rules aims to teach readers to be as imaginative as the narrator of this story, taking the bedtime story with them into the next day.

Readers are encouraged not to wear orange, “because you don’t want to miss a thing when the otters are singing, and the snails are lining up two by two and the trees are aslant at the midnight end of the garden.”

“And the sky… Look at the sky.”

The final image is of a huge moon over a lake. Next time readers see a moon like this, they will be prompted to remember this book and heed the invitation to delve deep into their imaginations. Readers are also reminded that as part of imaginative play, they can play with language:

“It’s going to be perfectly bimulous.”

OTHER OTTERS IN CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATION

I come from New Zealand and live in Australia so I’ve never seen an otter in my life. That didn’t stop me from reading a book called A Rumor of Otters when I was gifted it as a kid. The young adult novel was written by an American immigrant. The culture around New Zealand literature has since changed, with emphasis on a country’s native ecology.

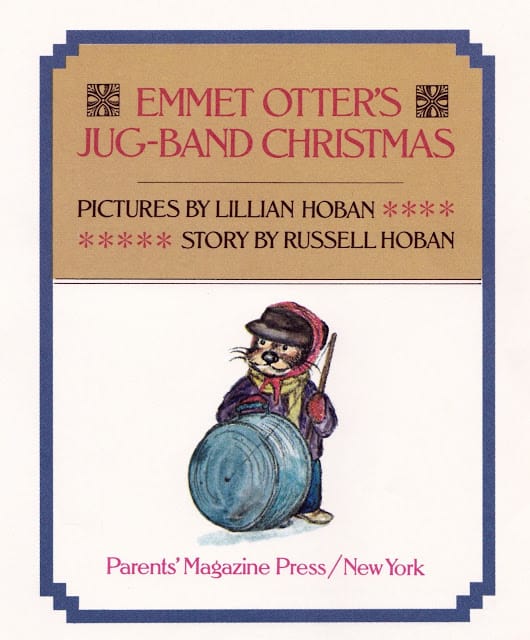

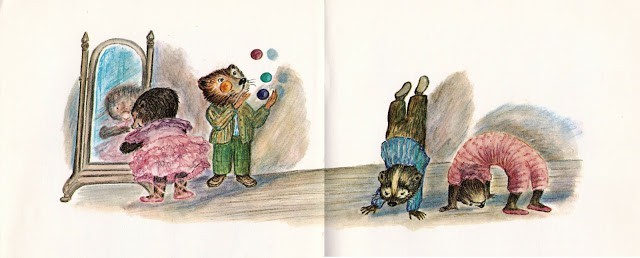

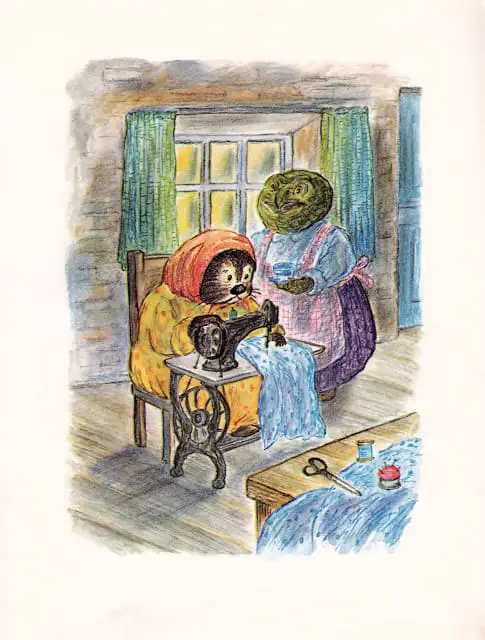

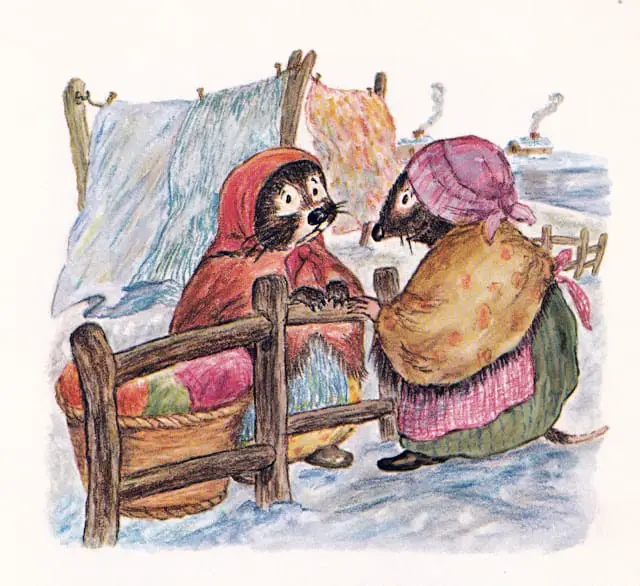

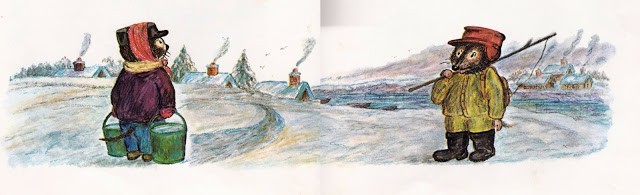

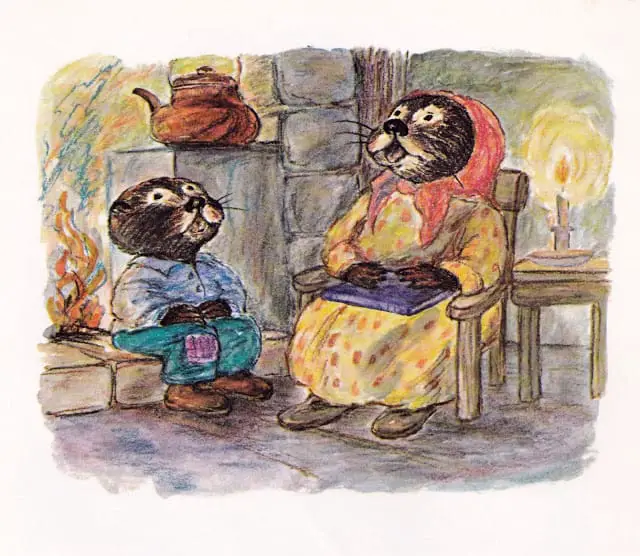

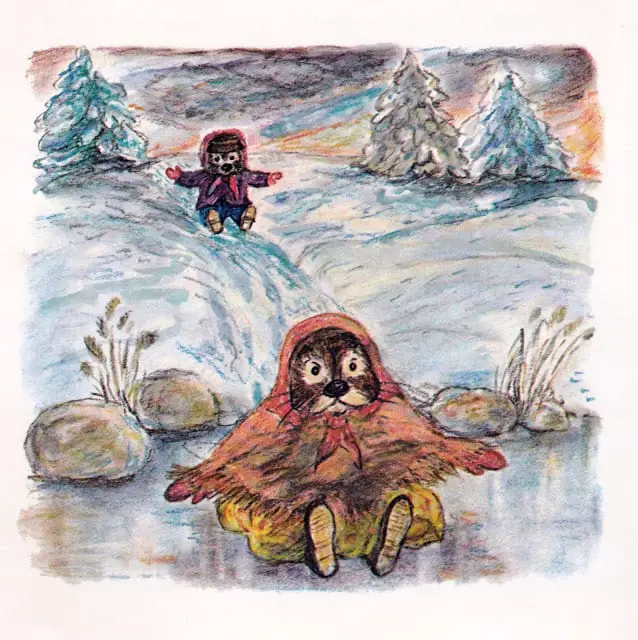

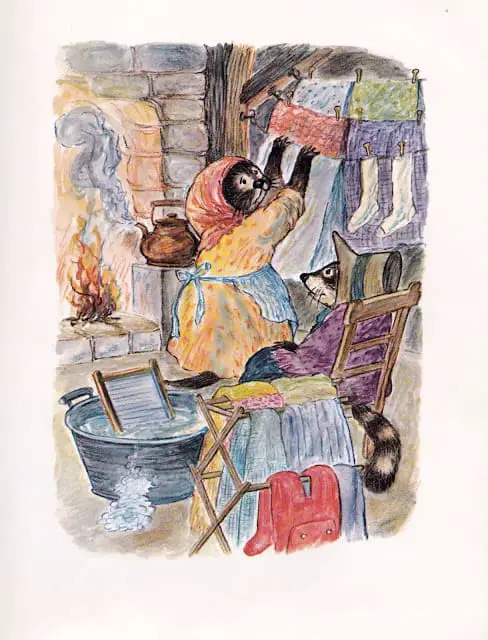

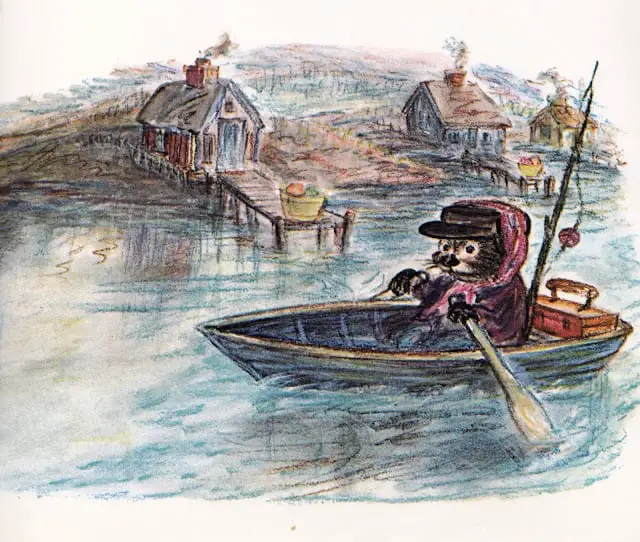

Emmet Otter’s Jug-Band Christmas by Russell Hoban, illustrated by Lillian Hoban (1971)

FURTHER READING

If you enjoyed When The Sky Is Like Lace, check out work illustrated by Ilon Wikland (born February 5, 1930).

The Twitter account In Otter News posts photographs of adorable otters.