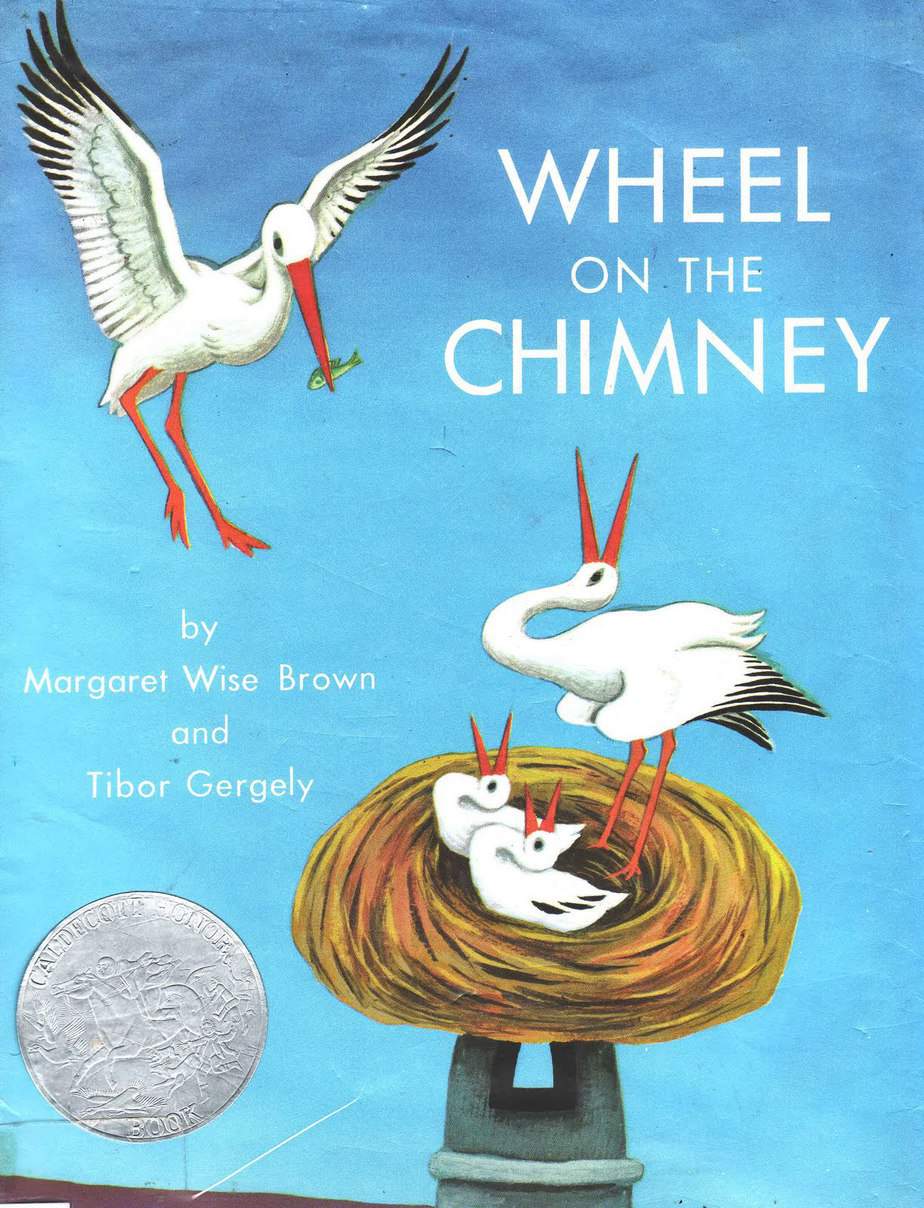

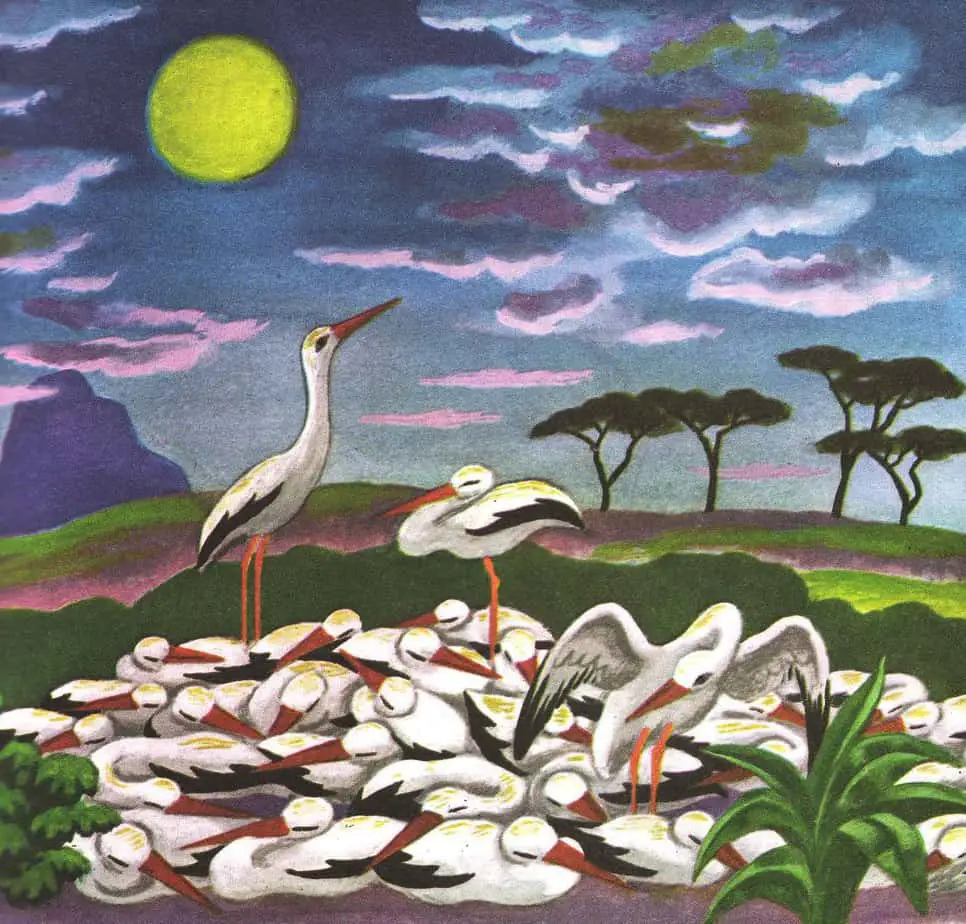

If you haven’t read Wheel On The Chimney (1954) by Margaret Wise Brown and Tibor Gergely, the Internet Archive has a video of a man reading it, against a backdrop of the most unsettling, grating, unpleasant muzak you’ve heard in your life.

Worse, this retro children’s story evinces a troubling conflation between blackness and villainy which publishers more commonly avoid in contemporary children’s books.

SETTING OF WHEEL ON THE CHIMNEY

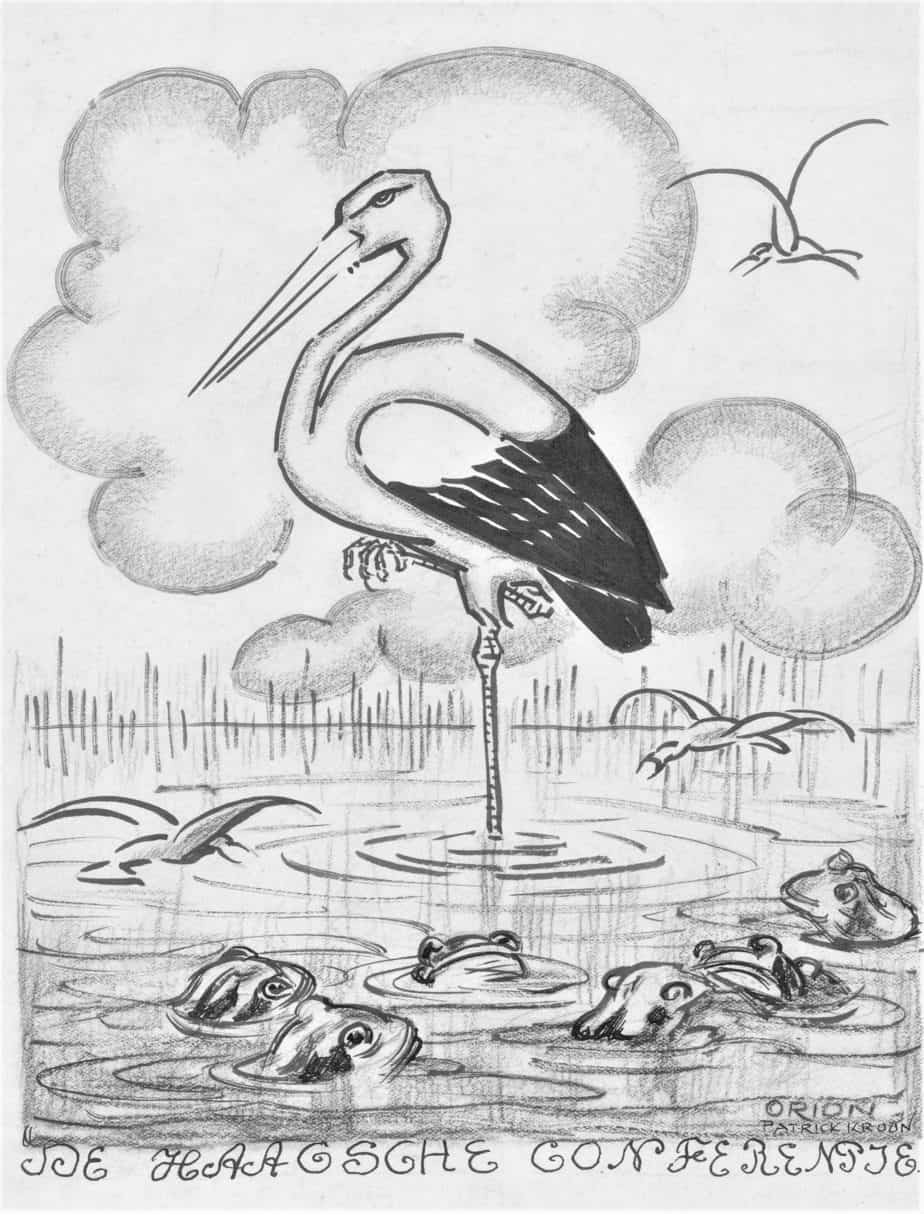

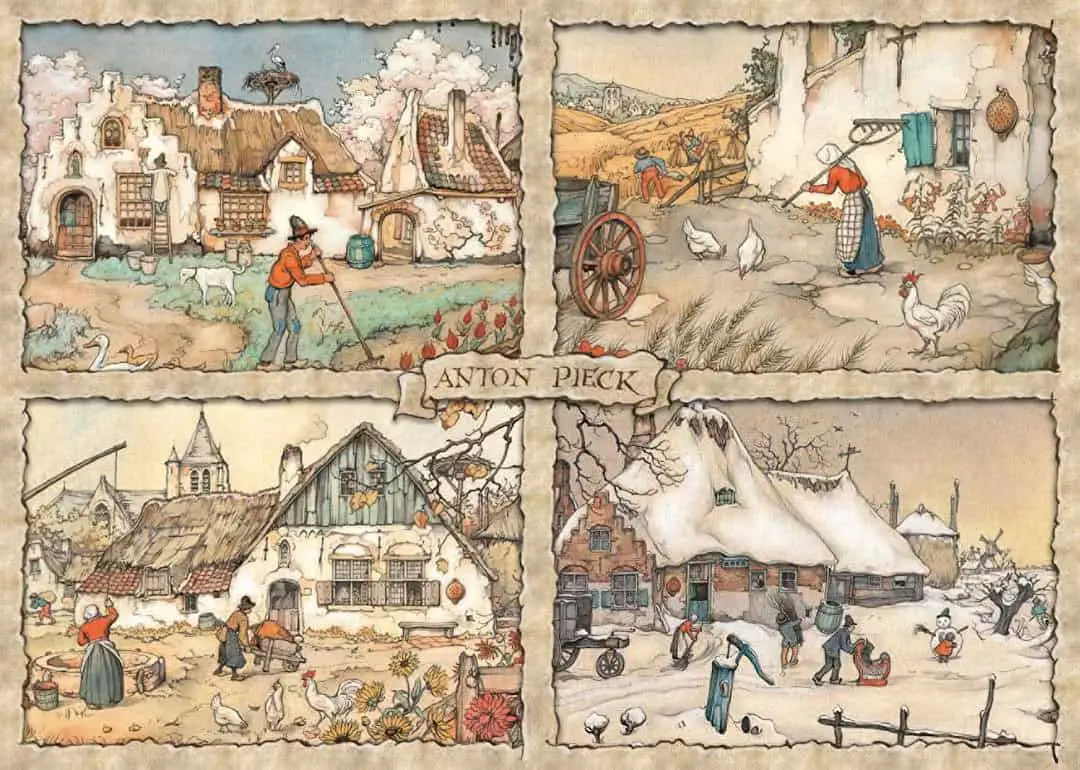

Wheel On The Chimney is a calm, bird-focused storified description of an old custom observed throughout various parts of Southern Europe. In parts of the Netherlands, for example, people attach a cartwheel to their chimneys hoping to attract nesting storks. The storks are considered very good luck to have on your roof. William Elliot Griffiths writes about this custom.

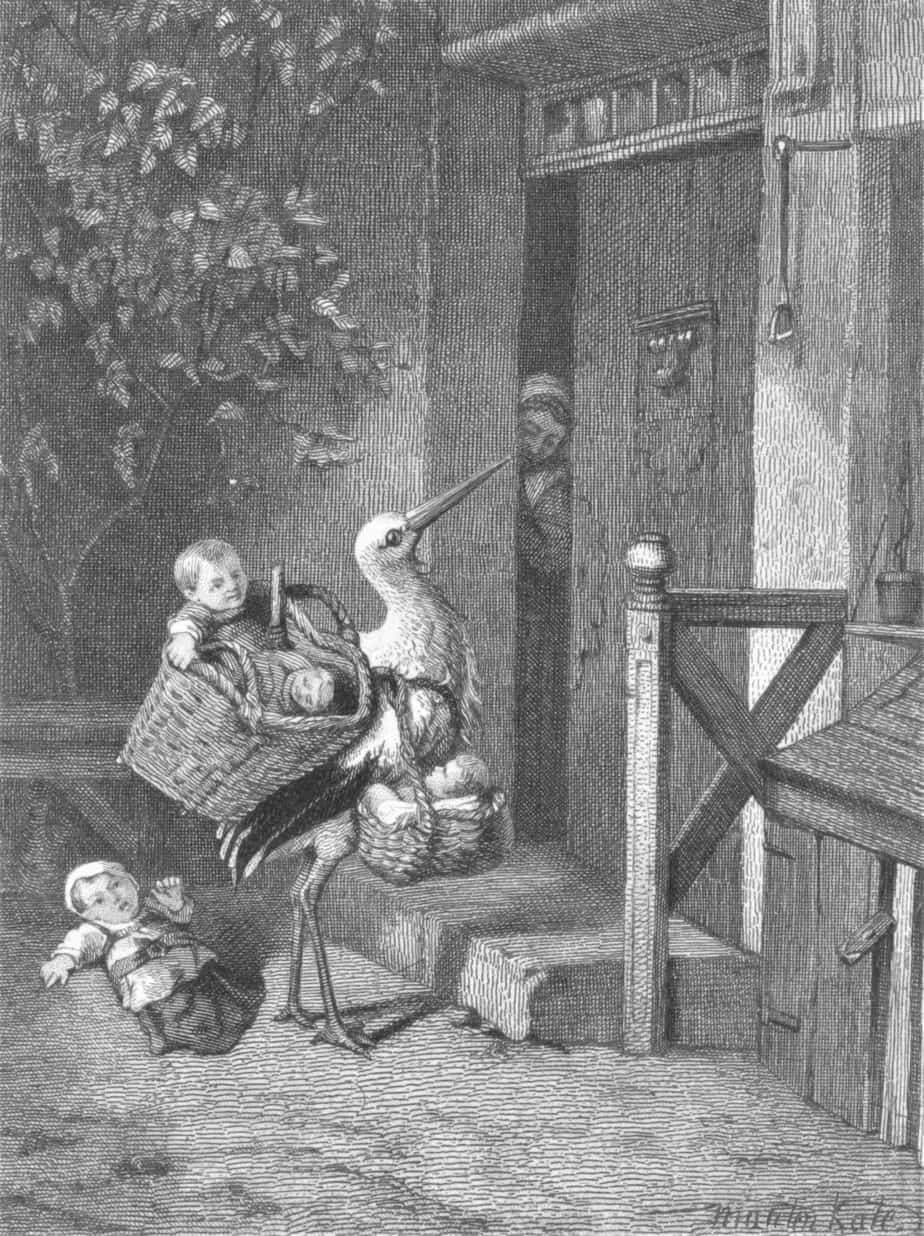

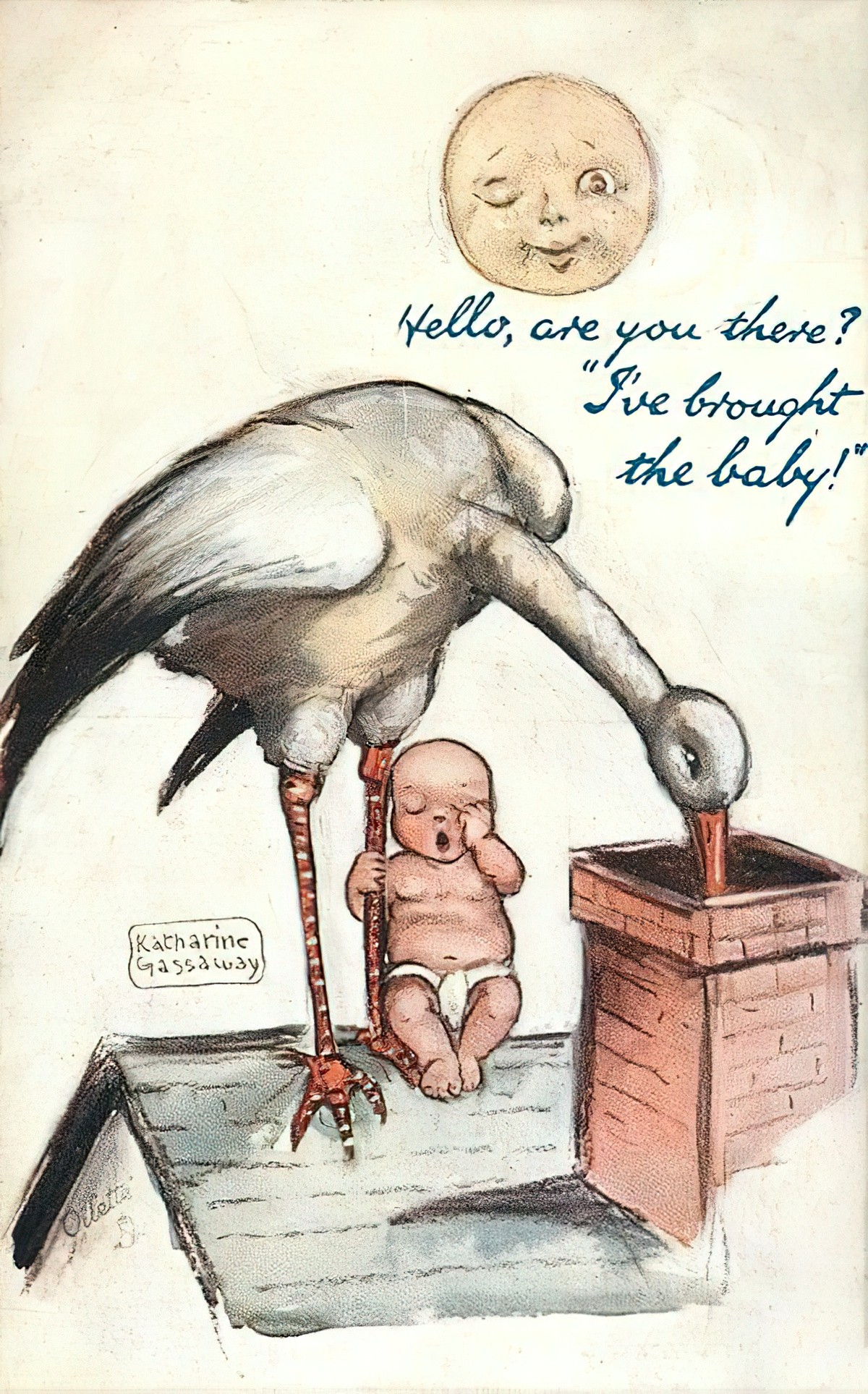

It’s interesting what people consider good luck and bad luck. In this case it’s not entirely arbitrary — new stork babies mean new life in general. Storks are commonly associated with the arrival of human babies, and many children have been euphemistically told that they were delivered by a stork, perhaps deposited down a chimney. (All sorts of things come via a chimney, not all of them good.)

THE ANCIENT CONNECTION BETWEEN STORKS AND BABIES

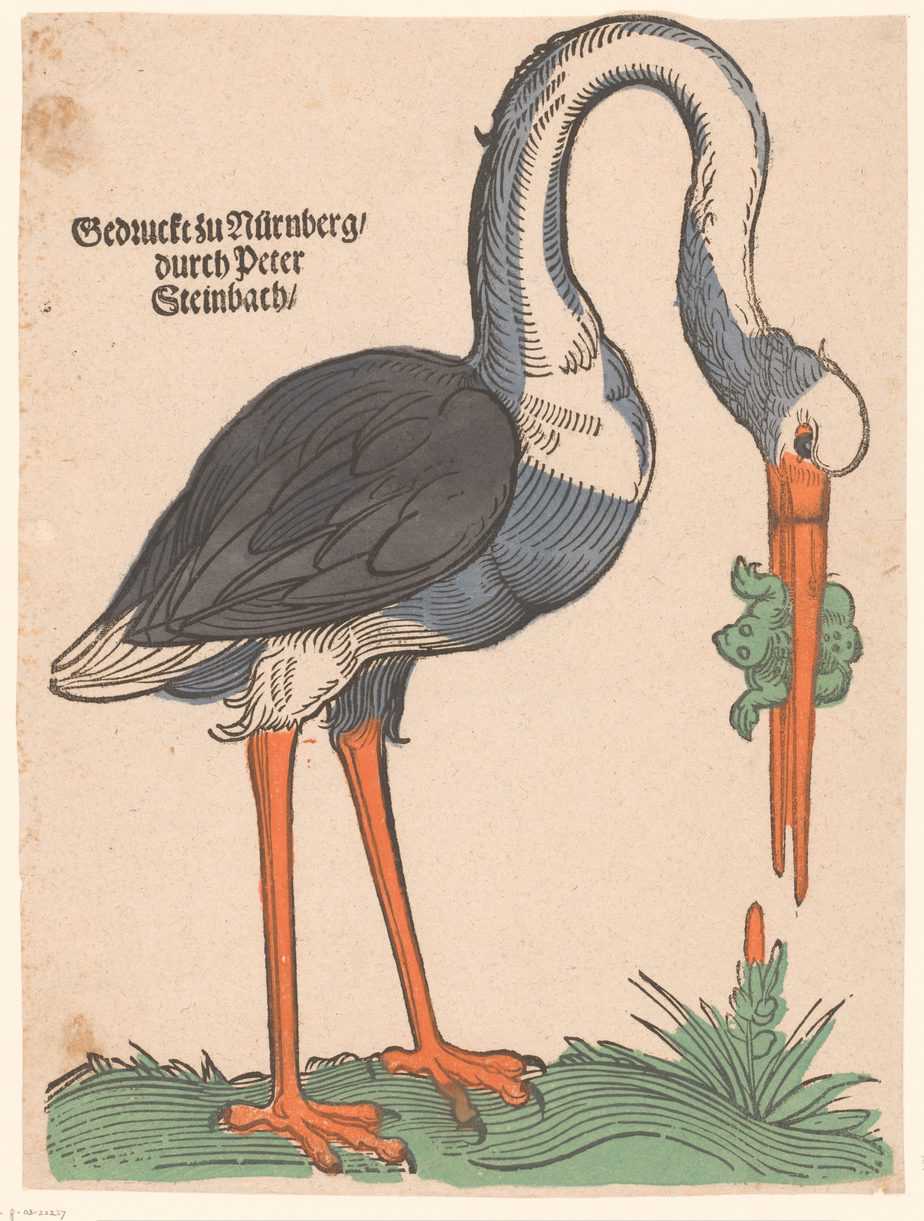

Why storks with the babies? Why not some other bird? Like many peristent narratives, it’s thought that the stork and baby story derives from the mythology of the Ancient Greeks, in this case the story of Hera, and because the Ancient Greeks were terribly misogynistic and also their gods evinced the full spectrum of human weakness, Hera grew jealous of another woman more beautiful than she was, so of course she was jealous, of course she became vengeful. (cf. Snow White etc.) Hera dealt with her jealously by turning this other woman (called Gerana or Oenoe) into a stork and stole her baby. In fact, that original myth was about a crane, not a stork, but they’re similar looking birds, so the confusion is understandable. The Ancient Greeks created imagery of Gerana flying as a stork with a baby dangling from her beak. Honestly, if you can turn another woman into an actual bird, why can’t you muster up the magic to turn your own self into a beautiful woman? I mean, make up alone works wonders; imagine what we could all do with the magic of transmogrification?

Margaret Wise Brown was a truly original writer, who gave the illusion — and it must be an illusion? — of writing intuitively without the nuisance of self-editing. In her picture books you’ll find all sorts of odd detail. She really did seem to channel the mind of a three-year-old. She didn’t appear to worry about pesky, well-established storytelling conventions like setting a scene before launching into story, and this was to her advantage, because the first thing a storyteller must do is create empathetic or interesting characters, especially when writing for children.

In this case, unless you are already familiar with the custom of wheels on roofs, the first thing you might think when you open this book is, What? Why is there a wheel on the chimney? And where is this so-called wheel? Is it the nest? Are we calling that nest thing a wheel, now? Tibor Gergely’s illustration doesn’t fill the knowledge gap for you either, because on the opening pages we don’t see the cartwheel poking out from beneath the storks’ nest. Only once the stork family are established as sympathetic characters are we told about that mysterious wheel on the chimney — why it is there and who put it there, and the thinking behind the custom.

… and the story starts all over again.

Wheel On The Chimney, final line

The story is a cyclical one, suggesting at the end that the entire process of migration and breeding will keep happening year after year, because although this was a story about one particular set of characters, the cycle of life goes on forever and ever. This is a reassuring thought, especially for the armageddonly-minded.

SILENCE EQUALS GOODNESS

It helps that storks are ‘a silent bird’, as underscored in Wise Brown’s text, juxtaposed against the unpleasantly noisy poultry in the barn. Noisy equals bad; silent equals noble, we deduce. Poor old chickens. This plays into an age-old ideology that the wisest creatures speak the least. Perhaps because birds vary widely in their vocalisations, we tend to use birds to hammer home this point; more commonly the owl:

There was an old owl who sat in an oak.

The more he watched; the less he spoke.

The less he spoke; the more he heard.

Why can’t we be like that wise old bird?

I suspect storks would not be so welcome on roofs were they noisy.

ANTHROPOMORPHISATION OF THE STORKS

The storks are unevenly anthropomorphised throughout the text. Writers and illustrators are entitled to anthropomorphise animals as their stories see fit, and animal characters commonly draw nearer and farther from humans across any given story. The opening sequence of Wheel On The Chimney suggests the storks will be getting the full-bird treatment, but soon you’ll notice (through your modern lens) that this is the perfect mid-20th century nuclear family, with a mother who stays home and looks after the young, a father who goes out to work and, to use another birdy idiom, a pigeon pair. Turn the page and we’re told that in fact the Daddy bird sometimes helps ‘at home’, though this is presented as a role reversal.

Now we run into ideological problems with anthropomorphising animals as humans, because the story covertly suggests that the mother ‘at home’ and the father out ‘at work’ is the natural order of things. Not so at all. Storks, along with all non-human animals, have no notion of gender and in fact stork parents divide parenting duties (ie. incubating and feeding) equally between them, but the homemaking motherly ideal of humans is imposed upon these storybook birds.

Here is a grim reality you won’t see in picture books: In the clip below, a stork mother throws one of her own baby chicks out of the nest to increase the survival chances for her other young. Evolution is inherently cruel; the stork mother is indeed practising good parenting, according to stork morality. Evolution has selected for brood reduction for a reason.

I suggest this is specifically stork morality, but brood reduction may be a grim reality of human cultures during times of extreme scarcity. The fear of it is everpresent. See popular horror such as Hansel and Gretel. When Hansel and Gretel’s mother (later softened to ‘step-mother’) sends two of her children out into the forest due to lack of food, what is that if not ‘brood reduction’ during a time of food scarcity?

In this particular story by Wise Brown, the storks continue to become more and more anthropomorphised, and it’s a subtle, covert shift. Later, one stork visits the captain of a boat and doesn’t seem to mind the captain draping his arm over his delicate back in a very human display of friendship. This stork is peak-human when we see him enjoying a feast fit for a… well, a human. The food is delivered on a tray.

GOODIES AND BADDIES

In a story built around Odyssean mythic structure (as most are), the main character will encounter a variety of other characters, some helpful, others unhelpful. The captain of the boat bound for Egypt provides sustenance and friendship, but once the stork is no longer weary from the storm, the stork moves on.

All good stories, even cosy children’s stories, need some kind of opposition as well as kind helpers, although if anyone is going to challenge that storytelling ‘rule’, it’ll be Margaret Wise Brown. Here she does nothing usefully subversive, unfortunately. I have long observed that the human construct of race and racism extends to animals. I first noticed this when I had a black labrador instead of a golden one. Golden (white) dogs are trusted more than their black siblings. When the black stork comes out of the forest in Wise Brown’s story, this is another clear example of ‘black equals sinister’, ‘white equals all things good and pure’.

This Manichean white/black divide is a very old, deeply-established, but highly damaging idea. Below, an explanation of why storks became associated with parenting in the first place:

The birds are big and white — linked to purity — and their nests are large, prominent and close to where people live. So, their good parenting behavior is highly evident.

Rachel Warren Chadd, co-author of “Birds: Myth, Lore and Legend” (Bloomsbury Natural History, 2016).

Contemporary picture book publishers are a little more mindful of conflating blackness with badness, even when the characters are ostensibly animals. When the black variety of storks fly up into the air, the very next image is of the stormy sky which sends the white storks off course. We all make use of cognitive biases when coding narrative; here, Wise Brown makes use of our human tendency to assume causality where none exists. These black birds caused the storm in the equally dark sky which sent the good and pure white birds off course. She doesn’t say that, of course. She doesn’t need to.

For more on the topic of blackness, racism and picture books, see this article at Social Justice Books. Illustrators must be mindful of conflating blackness with villiany, bad moods and monsters. Storytellers always rely on tropes, and tropes aren’t necessarily a bad thing. But some, like this one, require an urgent update.

EAST, WEST; NORTH, SOUTH

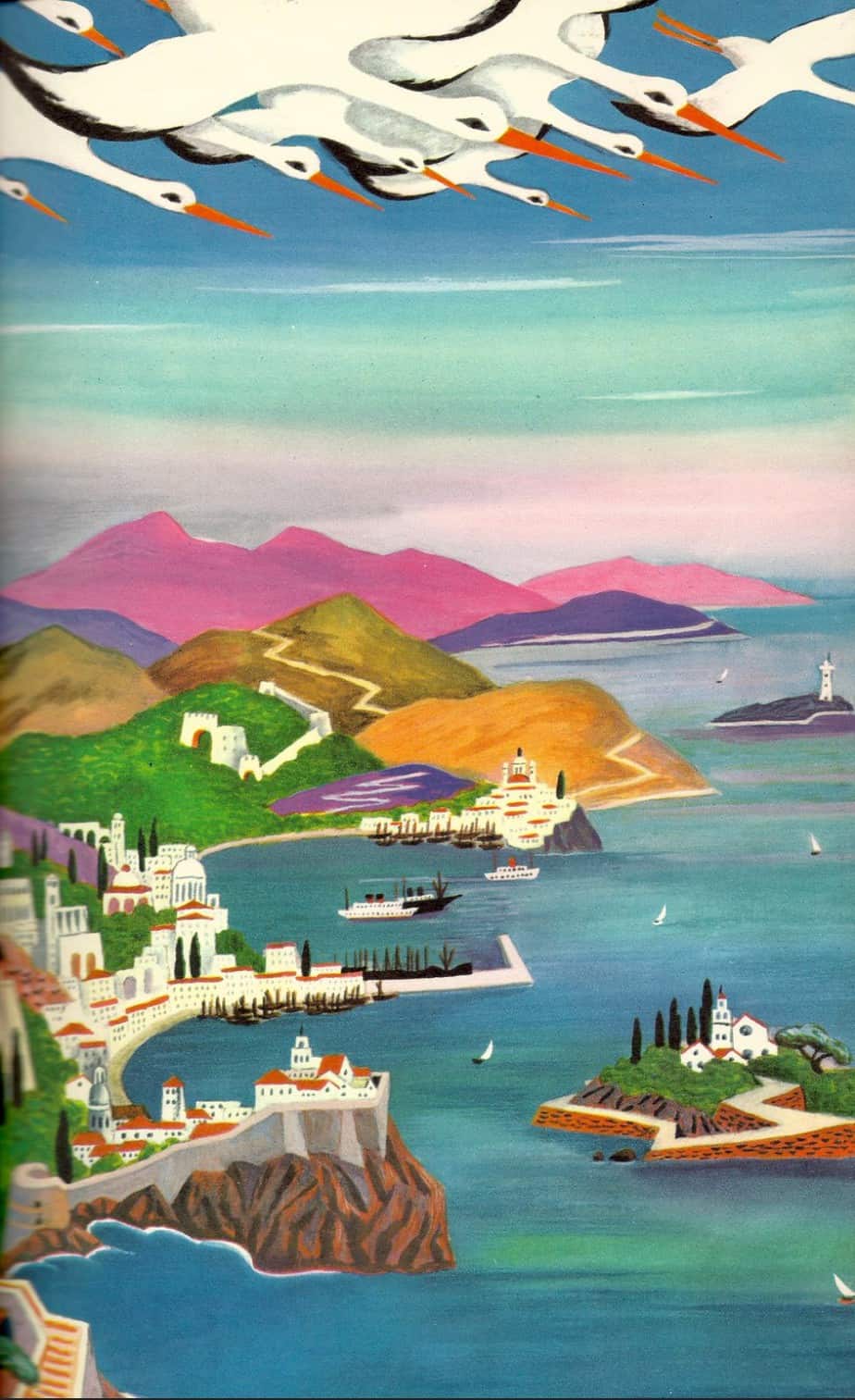

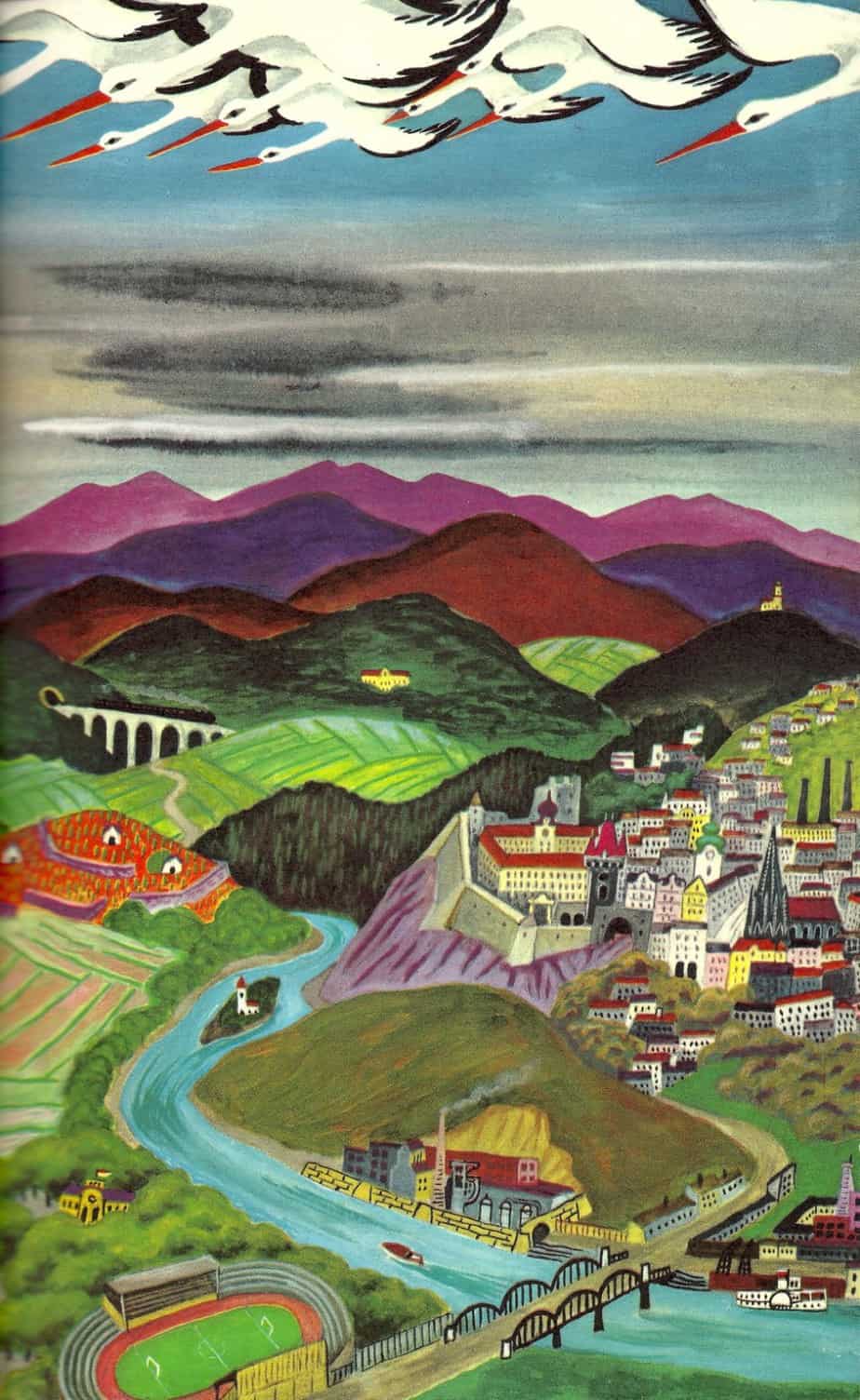

Tibor Gigely’s was himself Hungarian, where this wheel-on-the-chimney custom is observed. Gigely’s illustrations are beautiful, especially after the addition of the pink flamingoes.

The high angle scene below reminds me of Barbara Cooney’s work, with a similar palette and similarly folk art perspective.

Below, Tibor Gigely makes use of that general picture book rule in which characters move from left to right on their journey through a (Western-style) book, and only turn back when something happens to impede their journey. That stormy sky looks ominous, doesn’t it? However, Gigely also depicts the storks moving from right to left as we are told they migrate south. A book doesn’t have use of all four dimensions. When it comes to symbolism and cardinal directions, the illustrator only has use of ‘West’ (verso) and East (recto), so I find it interesting that Gigely takes the birds ‘West’ (through the book) to subtly, symbolically suggest South. We can already deduce that ‘North’ maps onto the picture book version of ‘East’ (meaning we turn the page from left to right).

THE NETHERLANDS AND STORKS