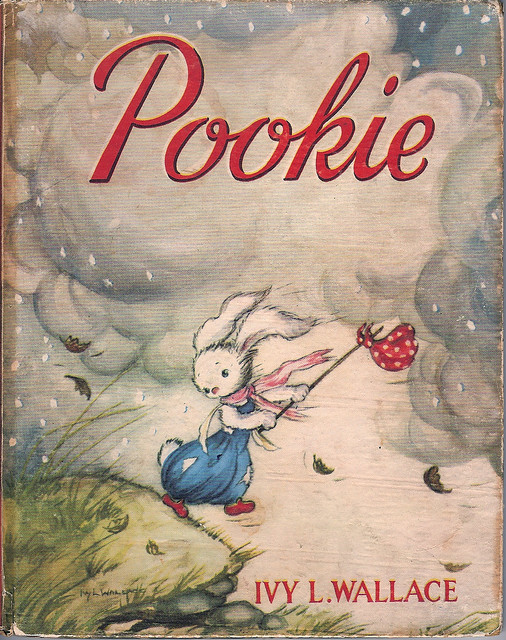

Pookie (1946) was my mother’s favourite series of picturebooks when she was very young, and she has a hardback copy held together with yellowed sticky tape. This one before me is a much later version, which has come out since in soft cover.

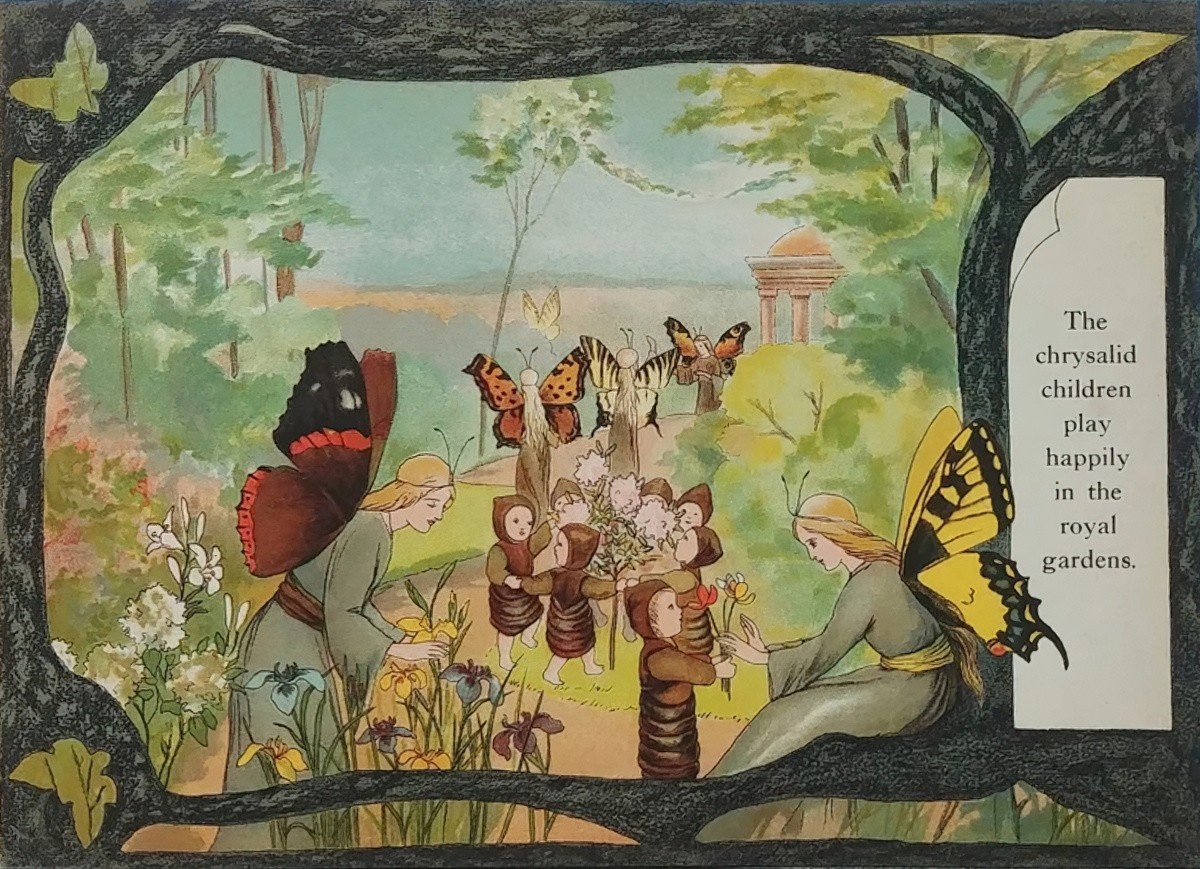

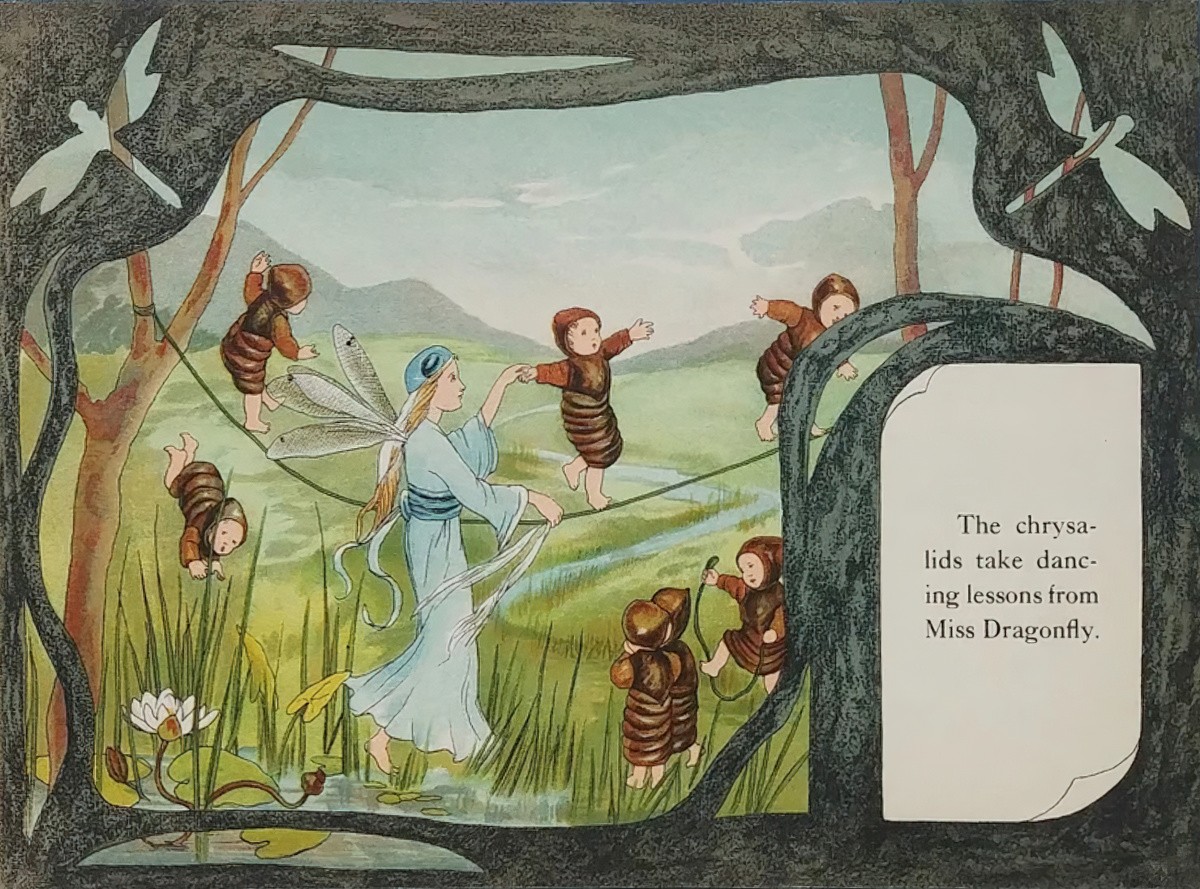

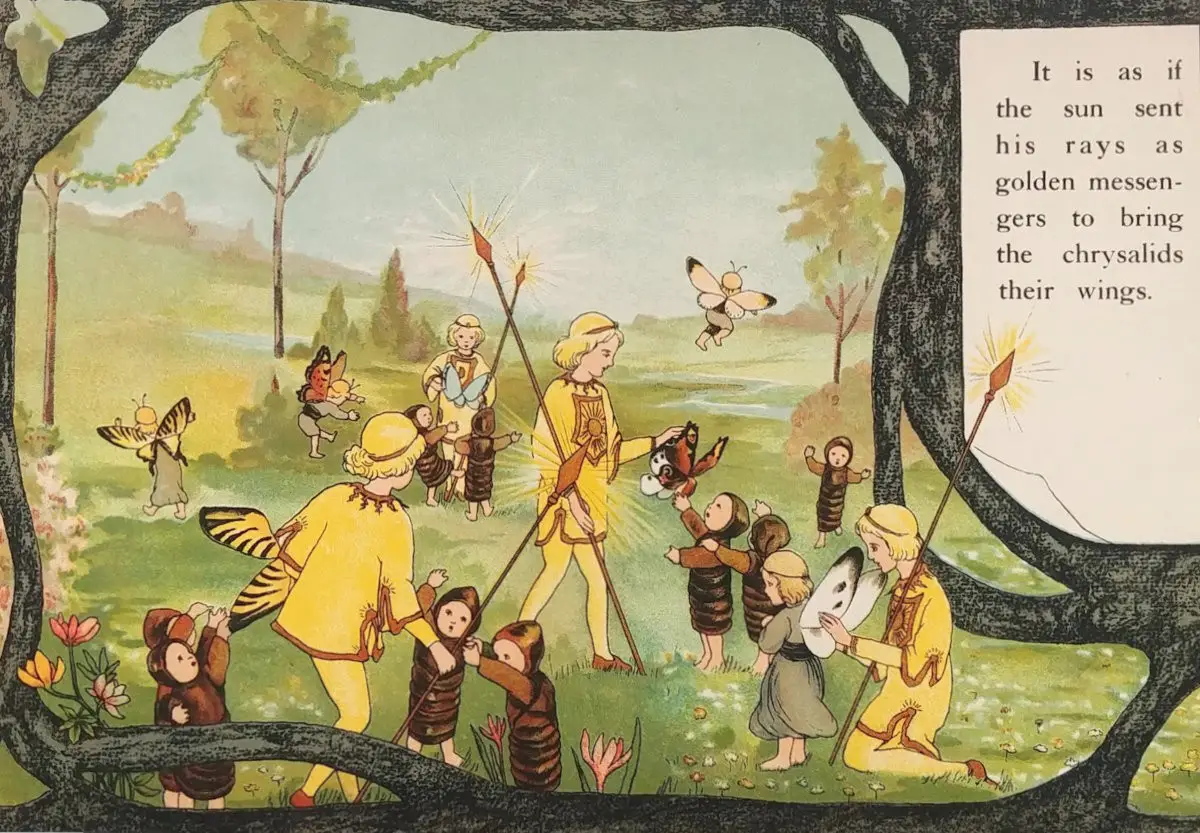

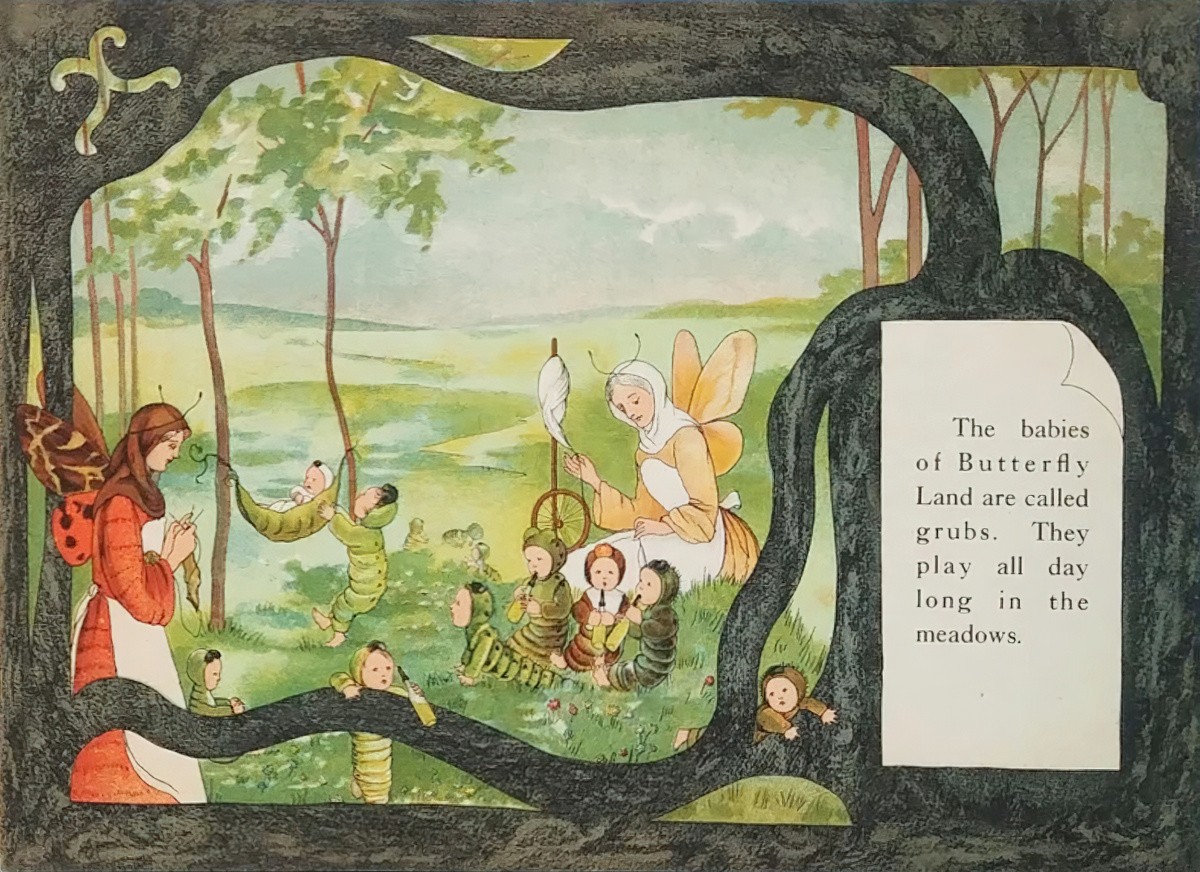

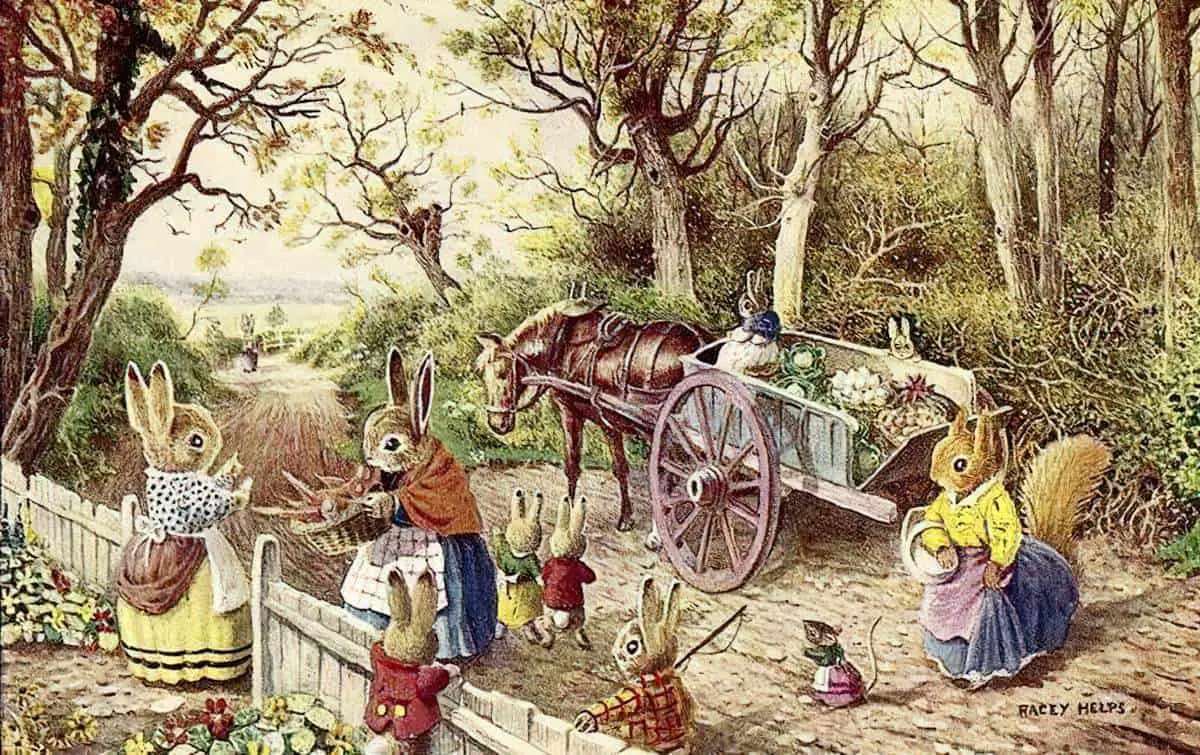

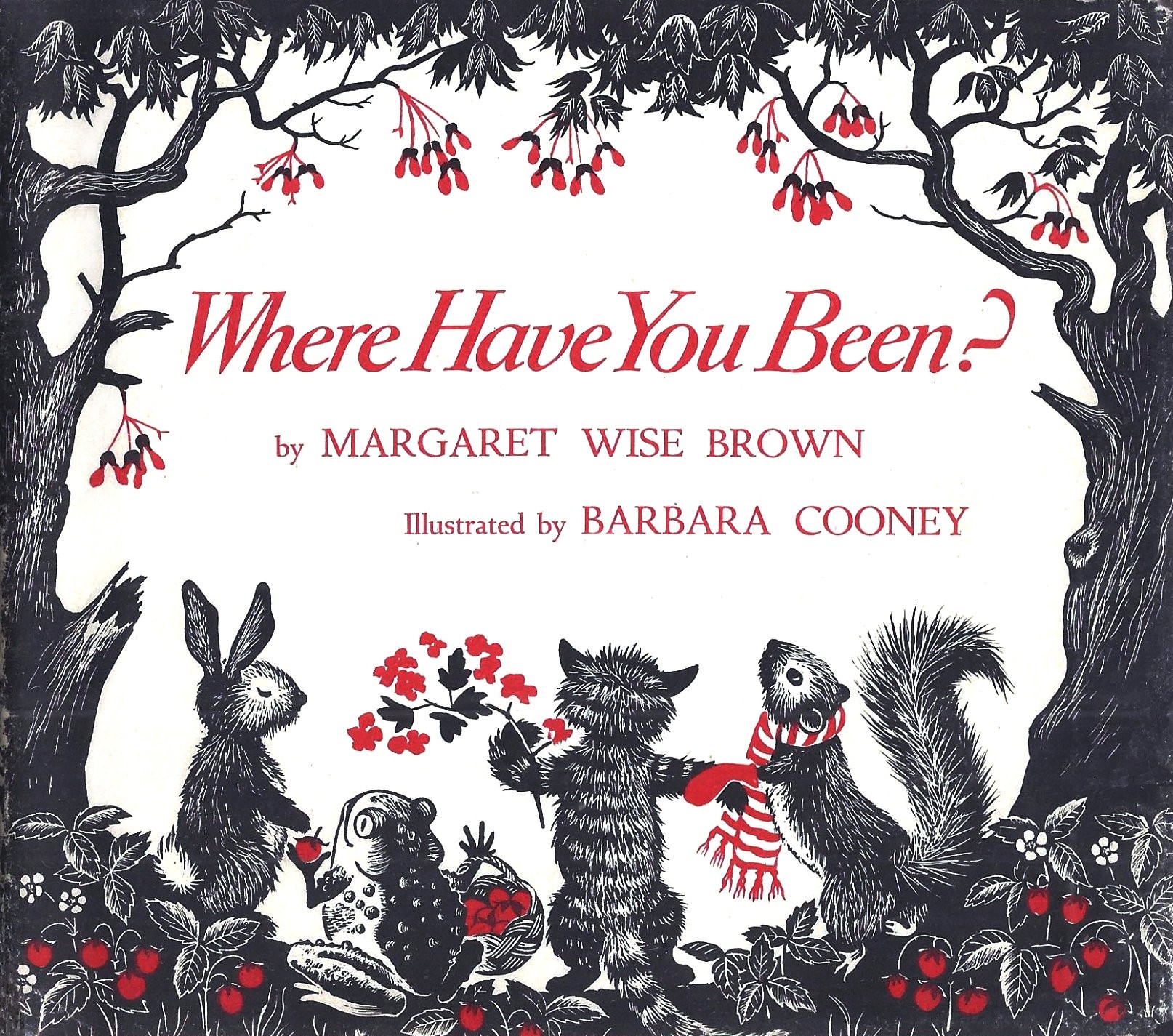

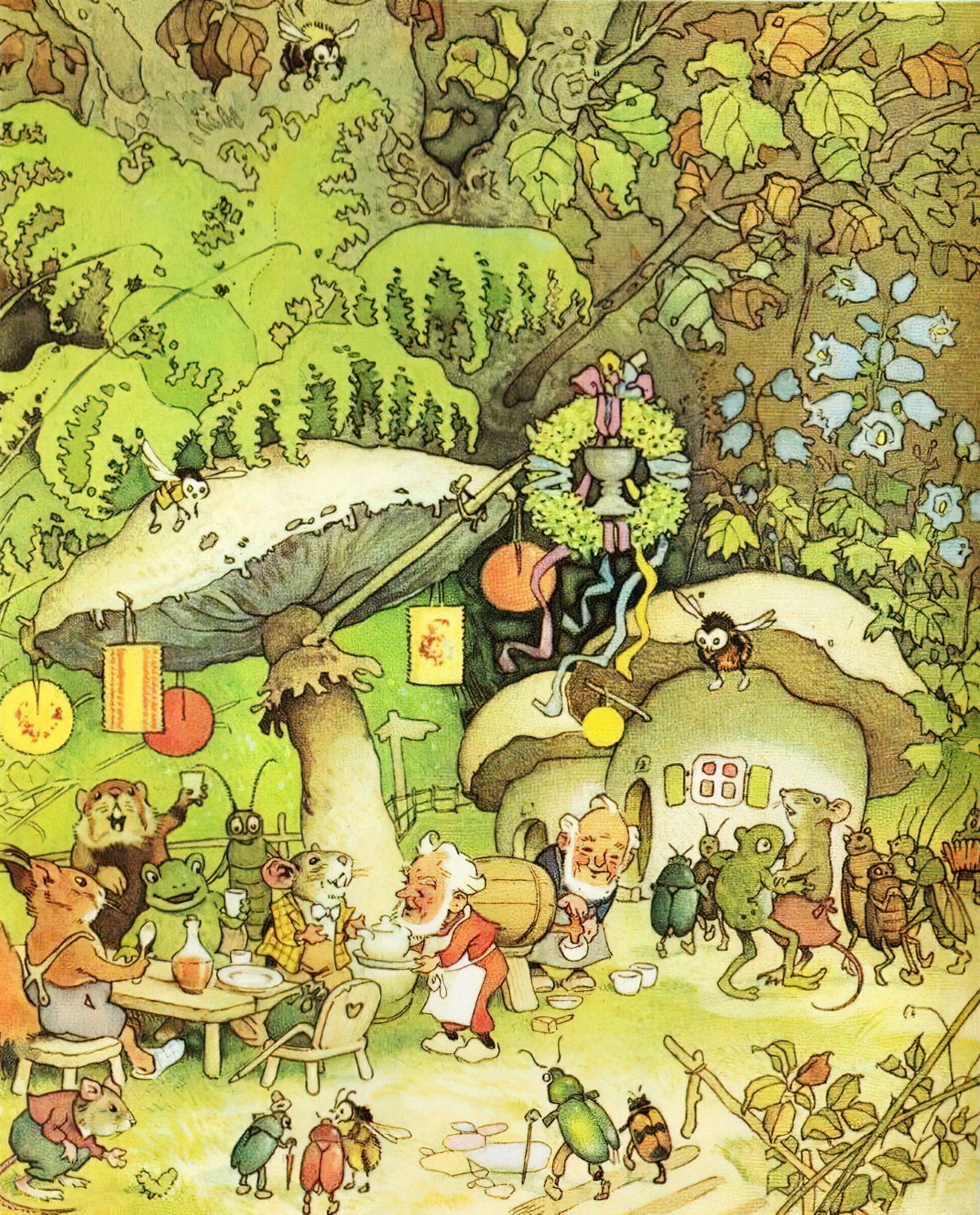

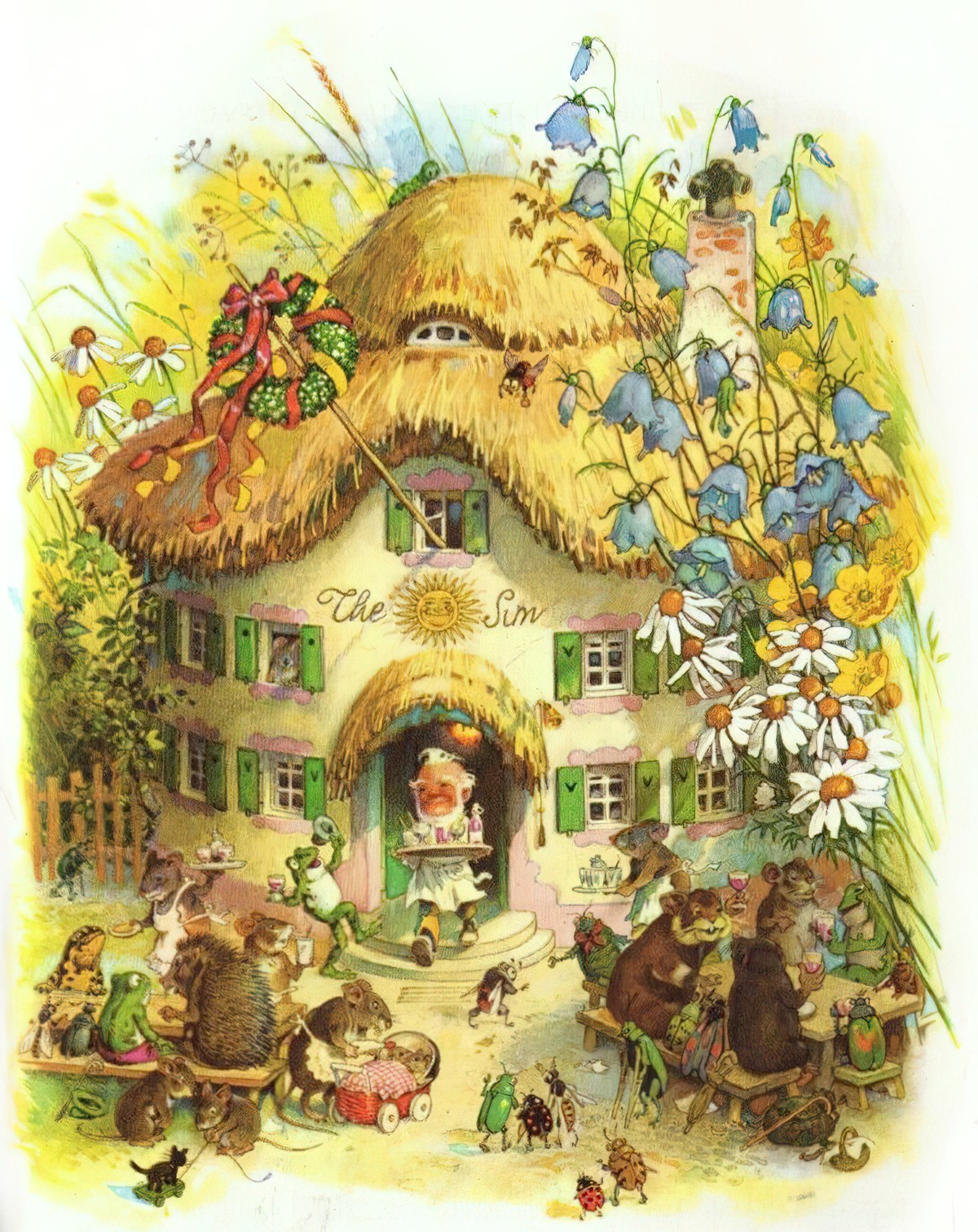

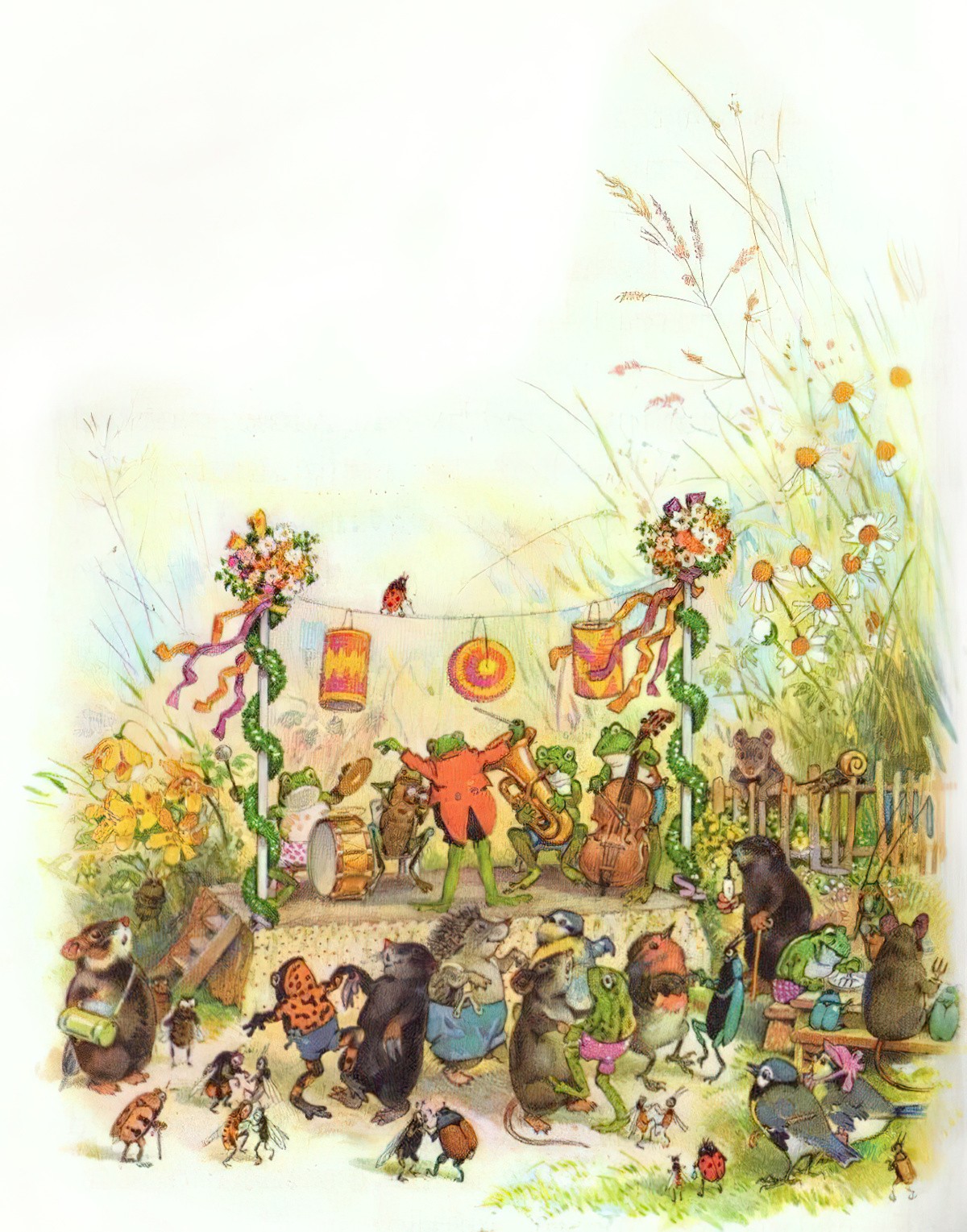

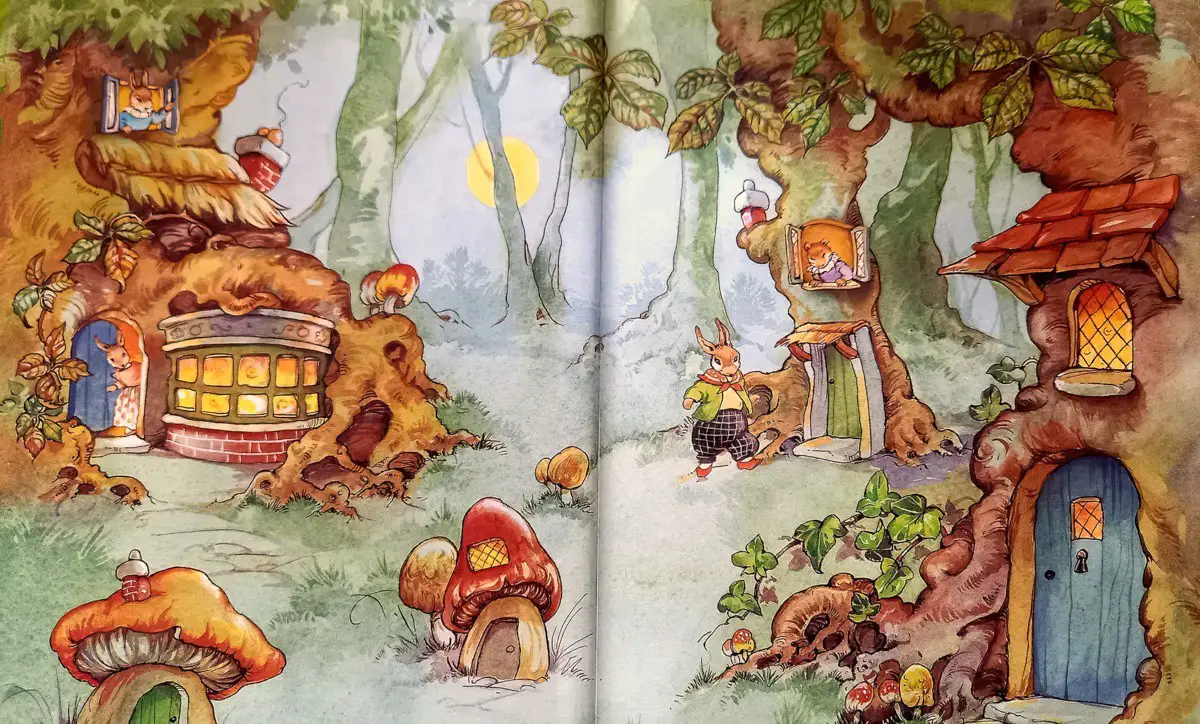

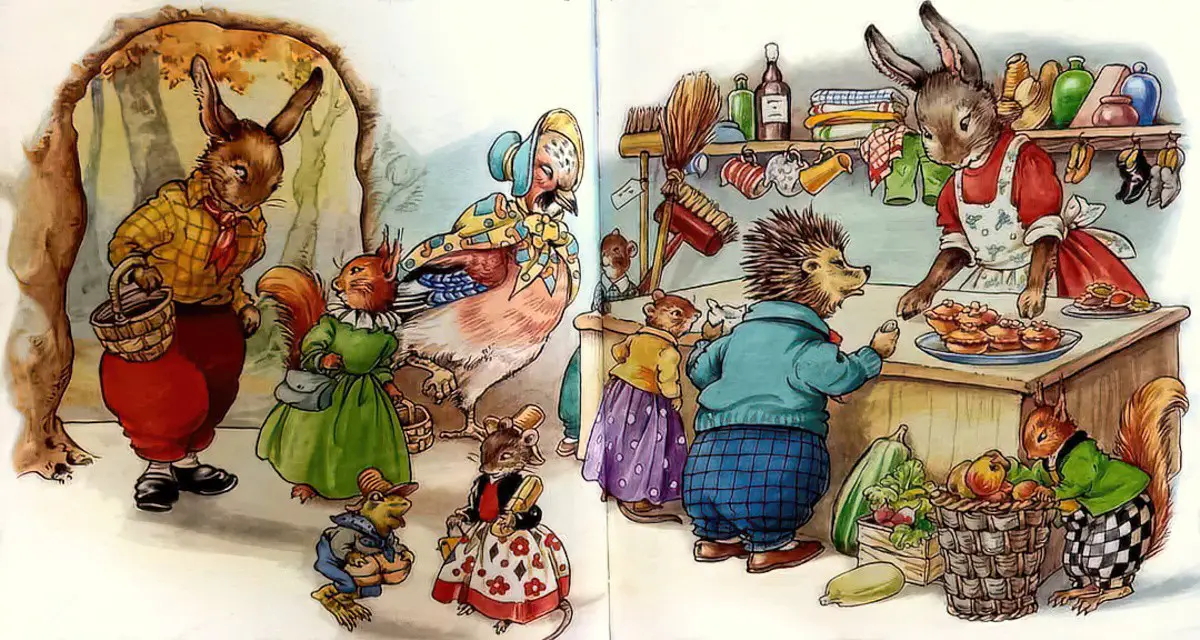

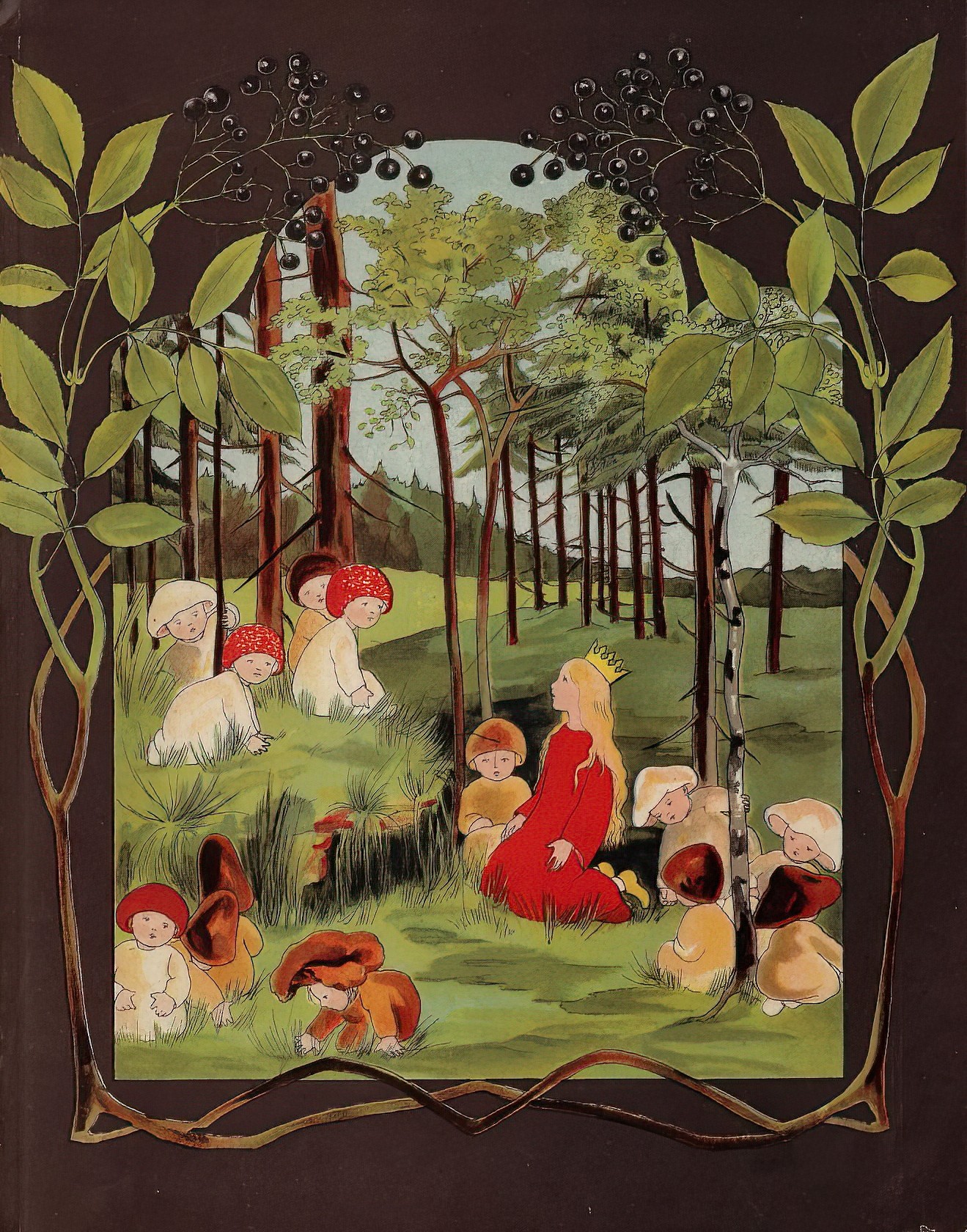

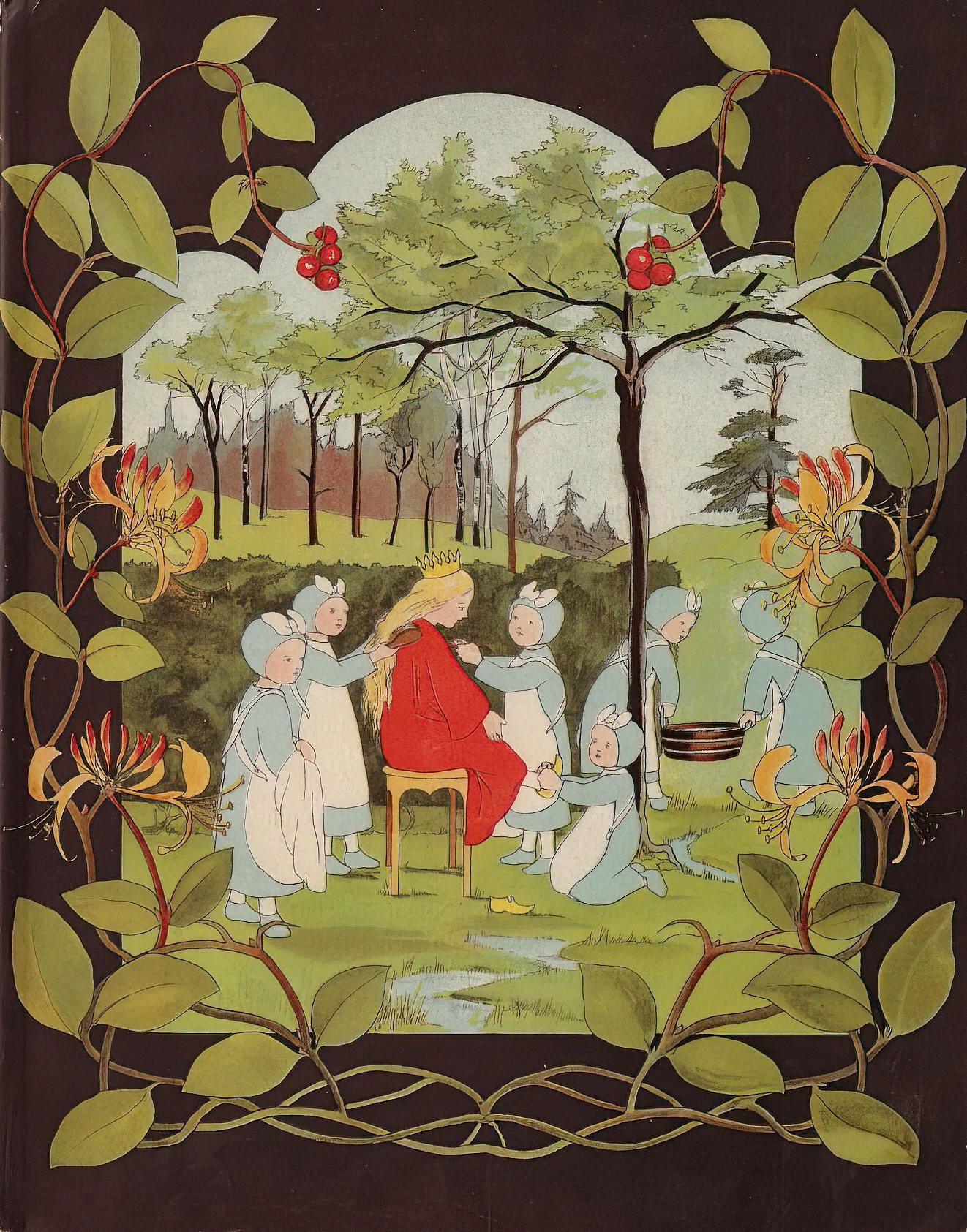

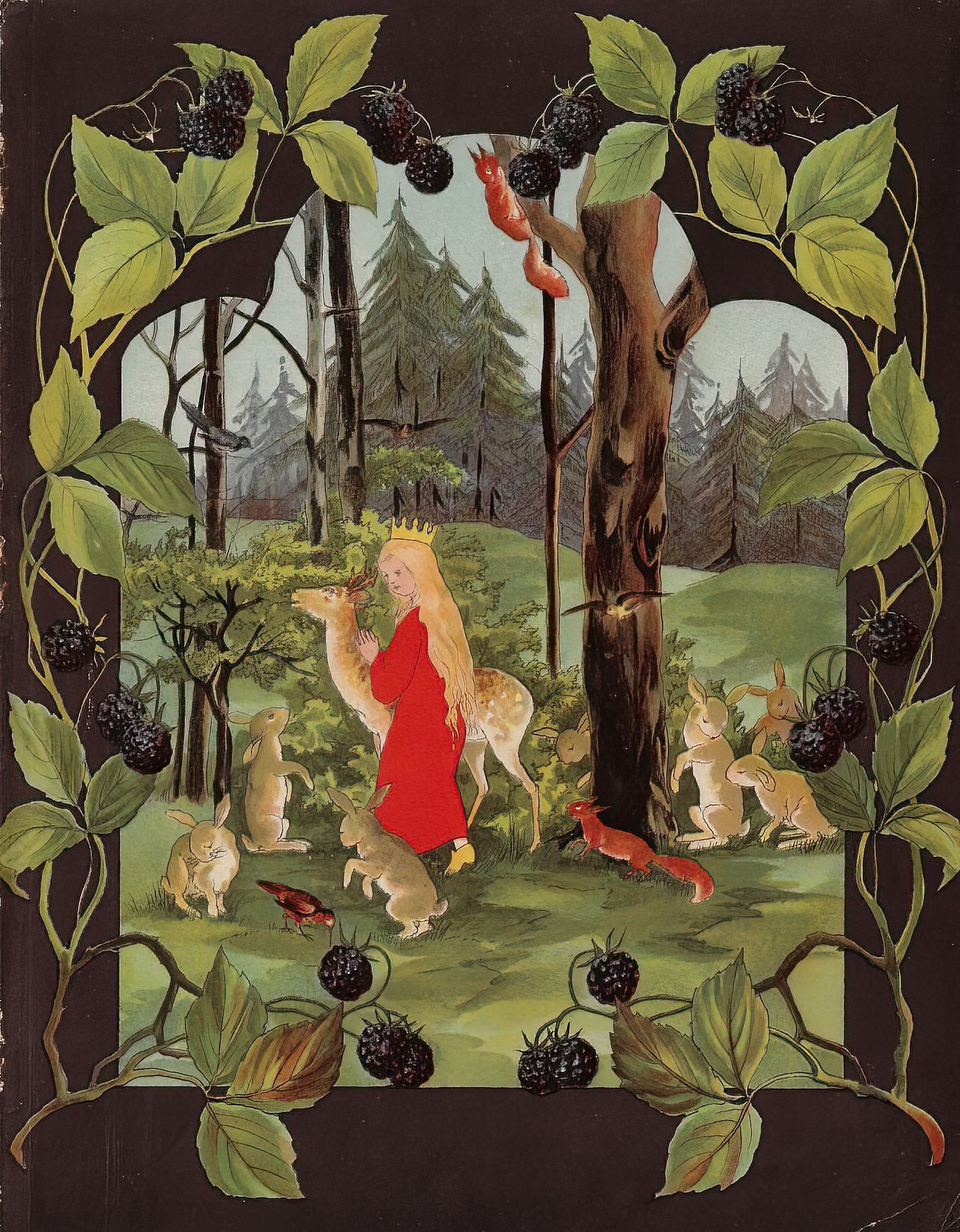

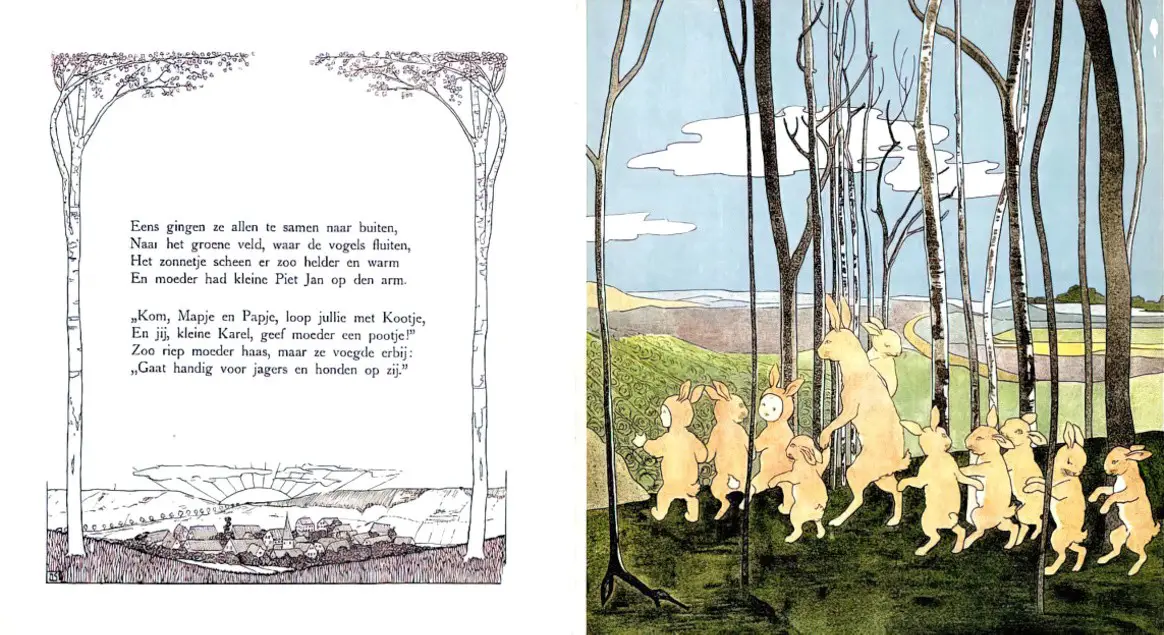

I wonder if fairies will make a true comeback. The illustrations in this book are marvelous. Like many fairy books of its time, the world Pookie inhabits is magical, with woodland creatures living happily in treetrunks, and magical little creatures in mushrooms. It reminds me of the illustrations in The Magic Faraway tree, which was brought to life in colour by Georgina Hargreaves. The language is Blyton-esque, with character names such as ‘Nommy-Nee’ and ‘Primrose-Dell’, in a world where you’re likely to run into a ‘pie-man’ who easily loses his temper because you don’t have any money. Like Blyton, Wallace makes use of popular rhymes and older fairytales. Ivy Wallace was also no doubt influenced by Beatrix Potter. “Mother rabbit said Pookie was more trouble to her than Wiggletail, Swifflekinds, Twinkletoes, Brighteyes, Tomasina, Bobasina and Weeny-One all put together!” At one point Pookie meets a man who would like to turn him into a pie. It’s easy to forget that until Beatrix Potter, animals hadn’t really been personified in picturebooks. She started a trend which only now is starting to wane a little bit. Talking animals dressed in clothes are no longer novel in themselves.

As for the story of Pookie, I’m not sure it holds up so well for modern children. I think ideally it would benefit from fewer words to go with those stunning pictures. I wonder if post-war children were still interested in fairies at a slightly older age, when they could cope with all of those words, or if post-war children had longer attention spans due to an absence of television. Maybe both.

Pookie is a rabbit fairy: two cute things in one. He sets out to ‘seek his fortune’ even though he has no idea what a fortune looks like. Along the way he learns that ‘fortune’ means different things to different people. He is eventually taken in by a very kind human-looking girl called Belinda who exclaims, ‘Why, his tiny heart is broken!” She then mends him with a kiss and Pookie knows that he has found his fortune.

It would be unusual these days to find a picturebook in which a fairy rabbit is male gender, in which ‘goblin tailors sat cross-legged on their toadstools, stitching away at filmy fairy frocks made of scented flower petals’, but this story isn’t otherwise gender-bending. The working world (teachers, merchants) is of course typical of its time — populated with men — and it would have to be a girl (a perfect wartime nurse in training) who tends to Pookie and mends his wounds, since kindness and love were not desirable traits in a man right after manly men saved us all in that war. Indeed, Belinda’s is a level of kindness I haven’t seen in any gender much, and even in modern children’s stories, kind boys are much more rare than kind girls, unless they’re also the introverted, shunned type. (The kind no boy would really want to emulate.)

And with lines such as, “Oh, Pookie, look at your wings now! All they needed was Love, Pookie! Look at them now!” this story is just a little bit twee for modern tastes. Or maybe just for my tastes. But I see why my little-girl-mum would have liked it.

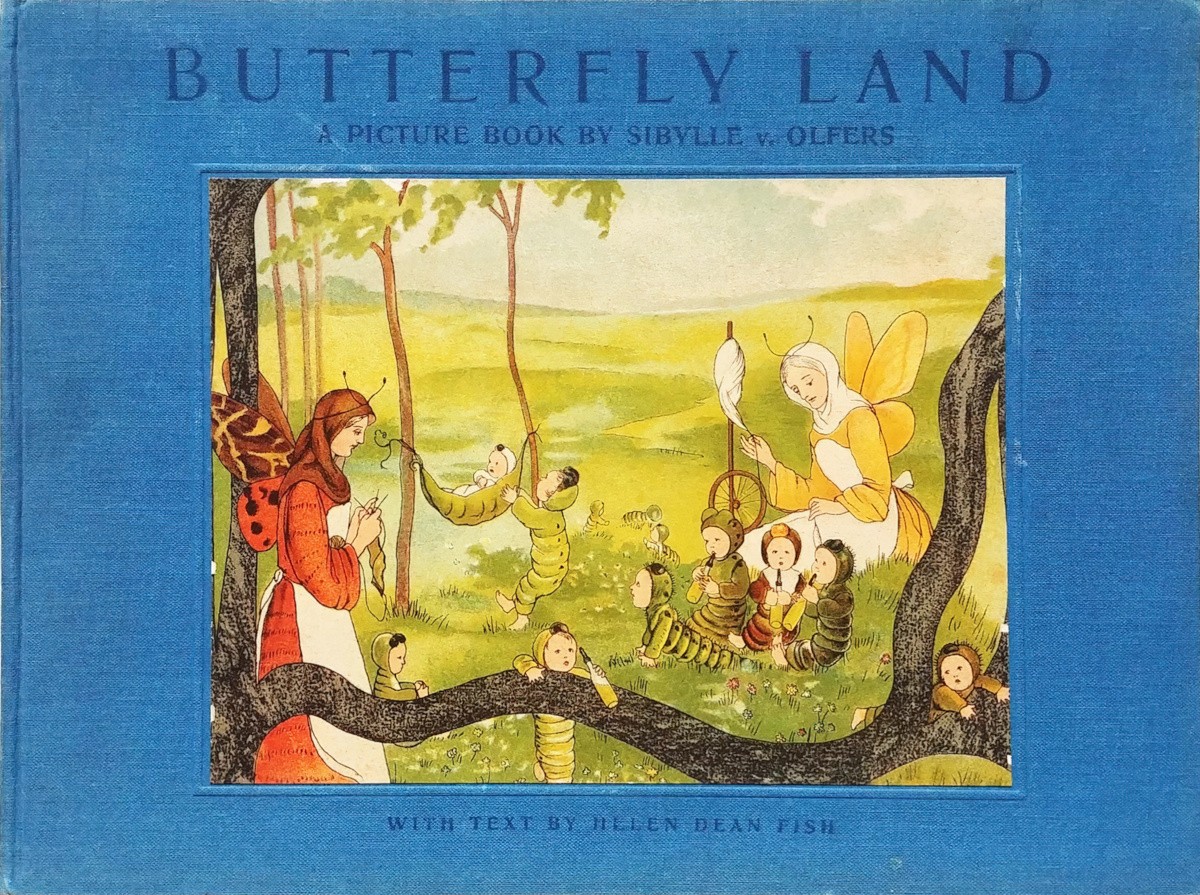

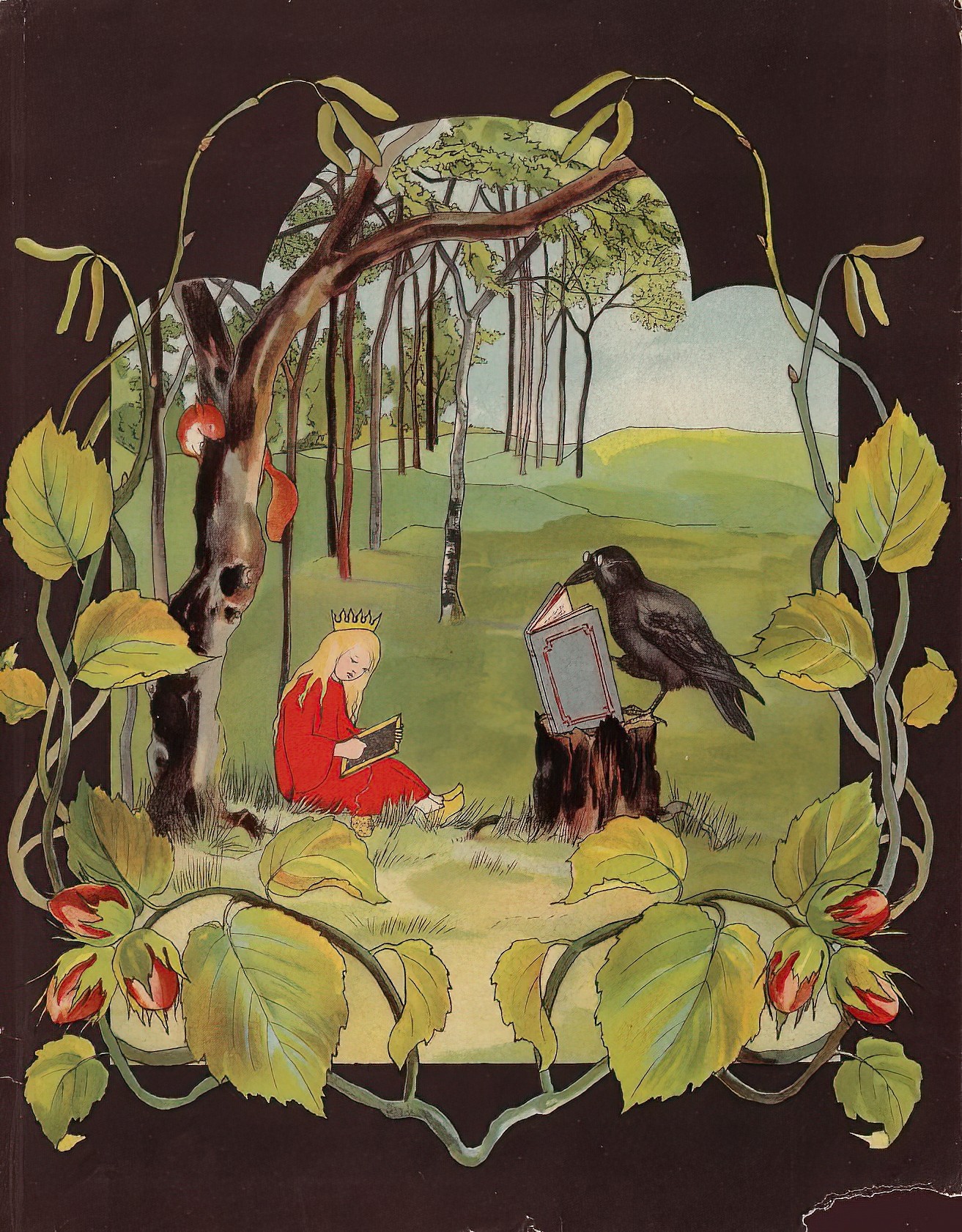

If you love the art nouveau borders of Sibylle v. Olfer’s illustrations, see more of her work in Beautiful Cosy Underground Scenes.