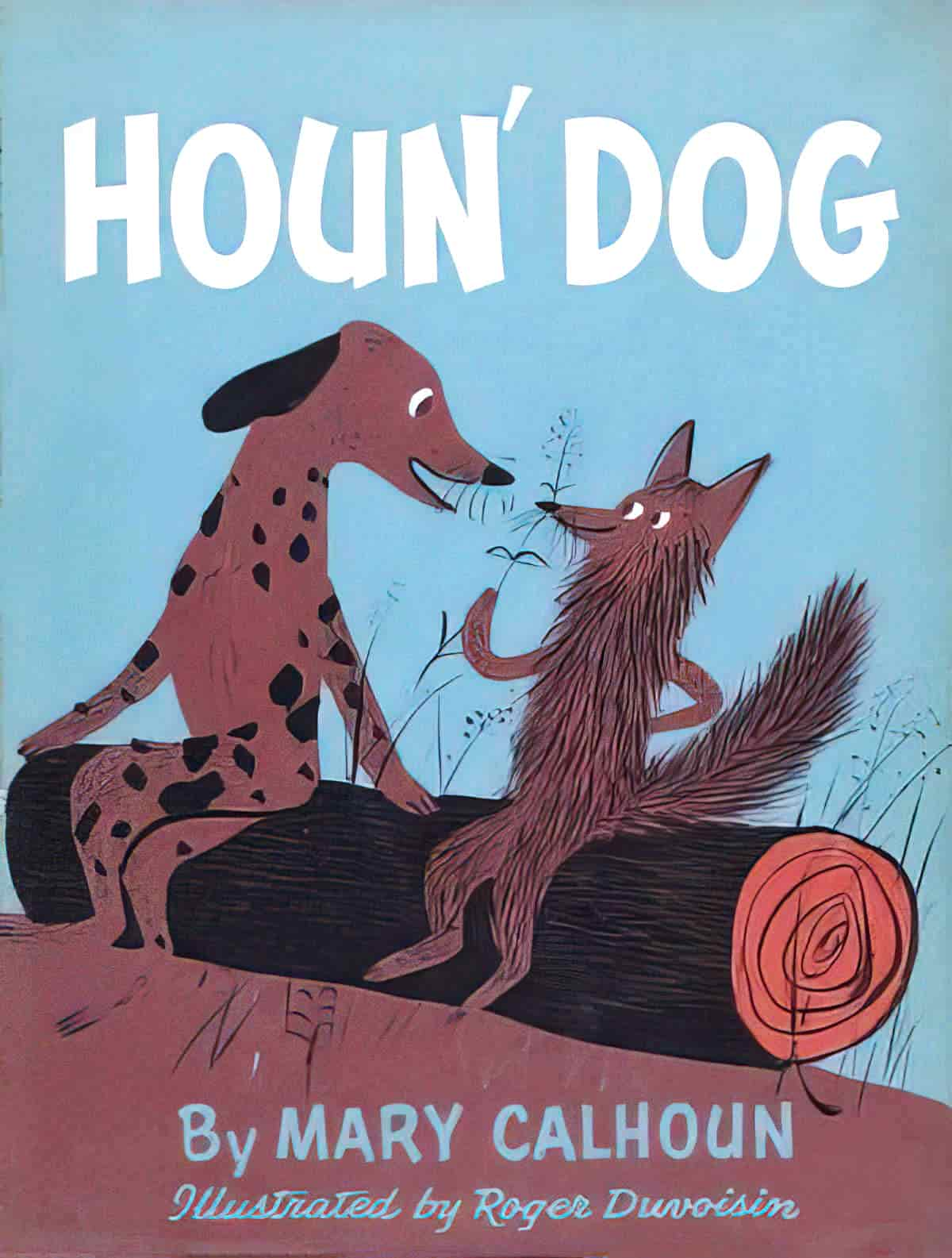

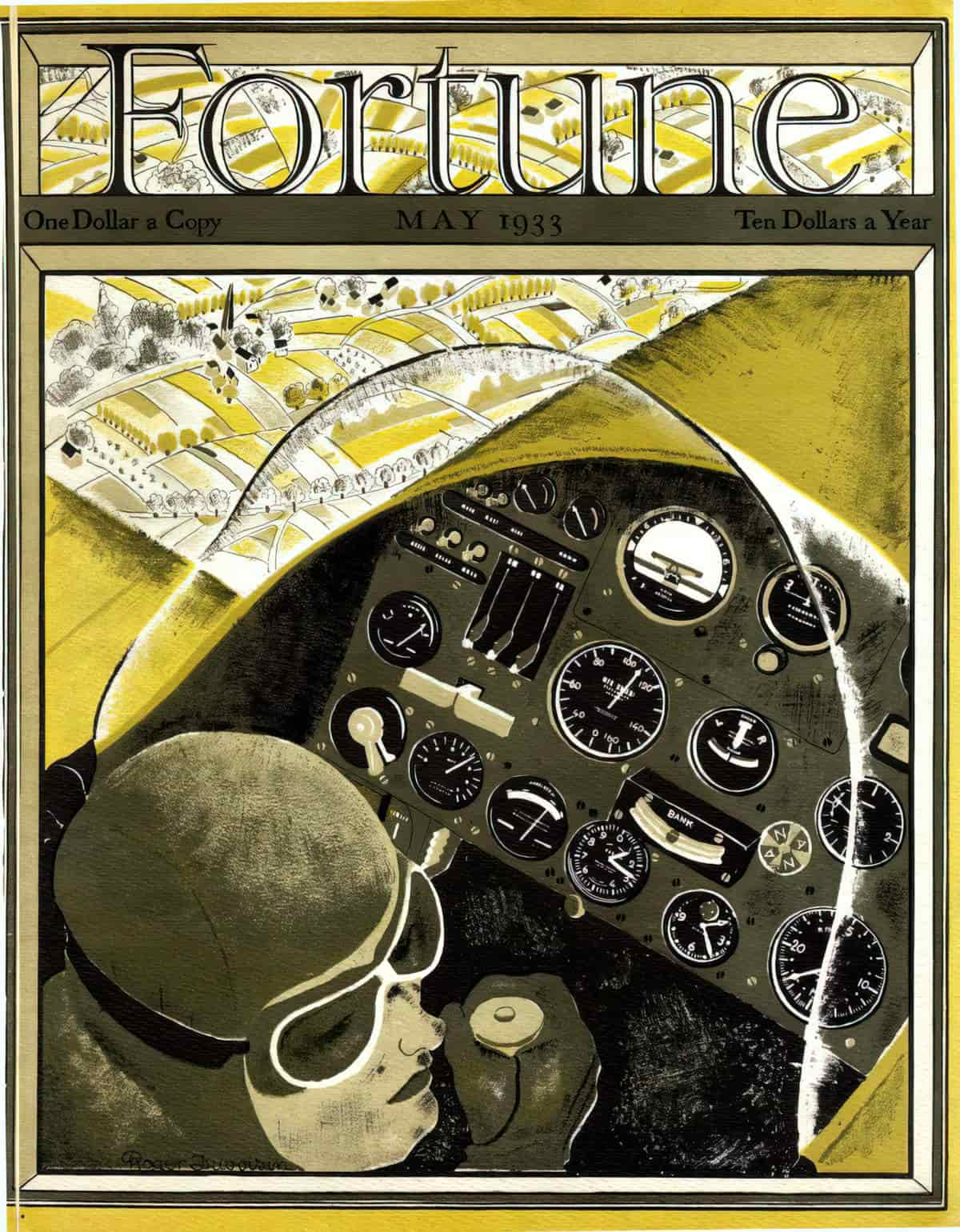

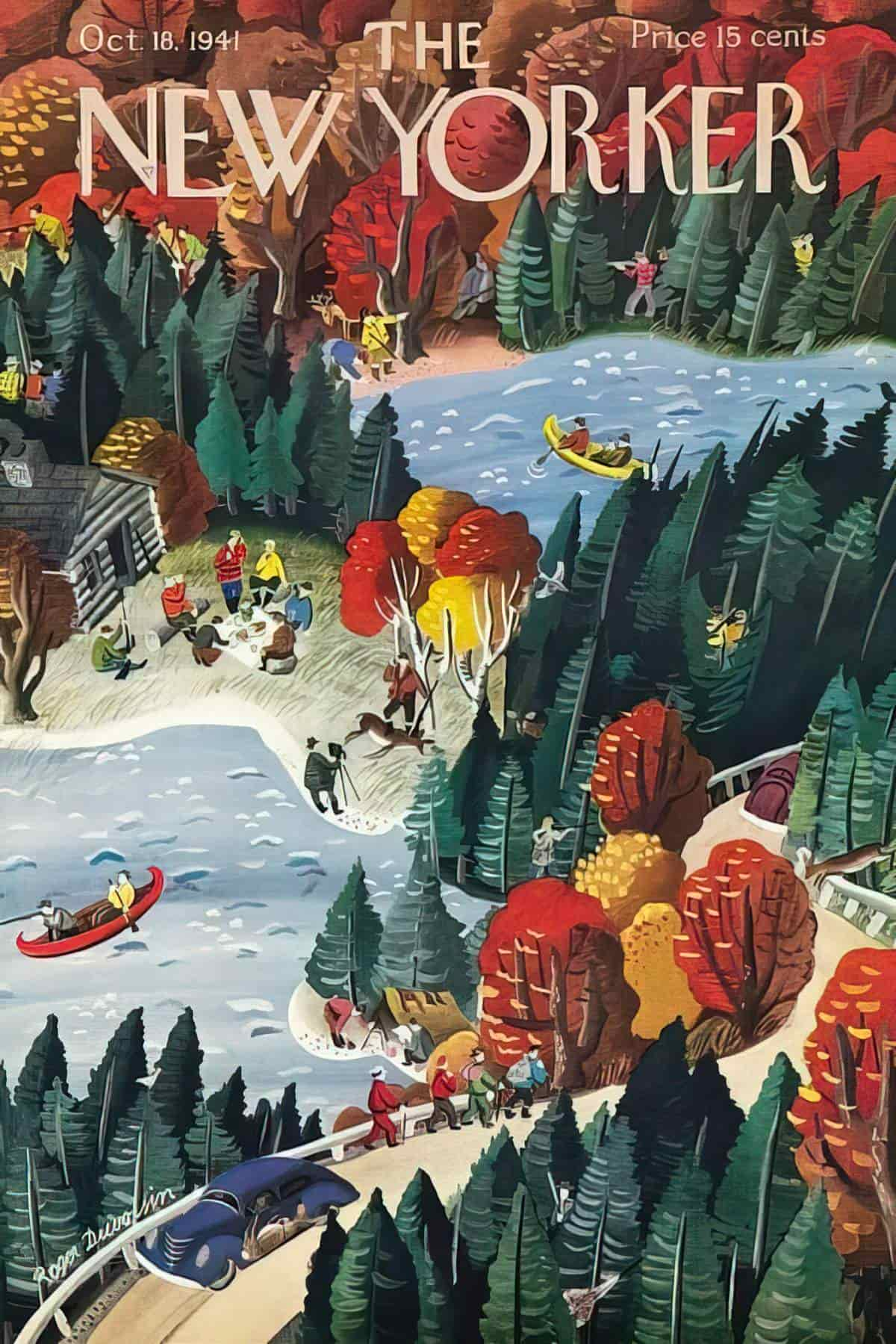

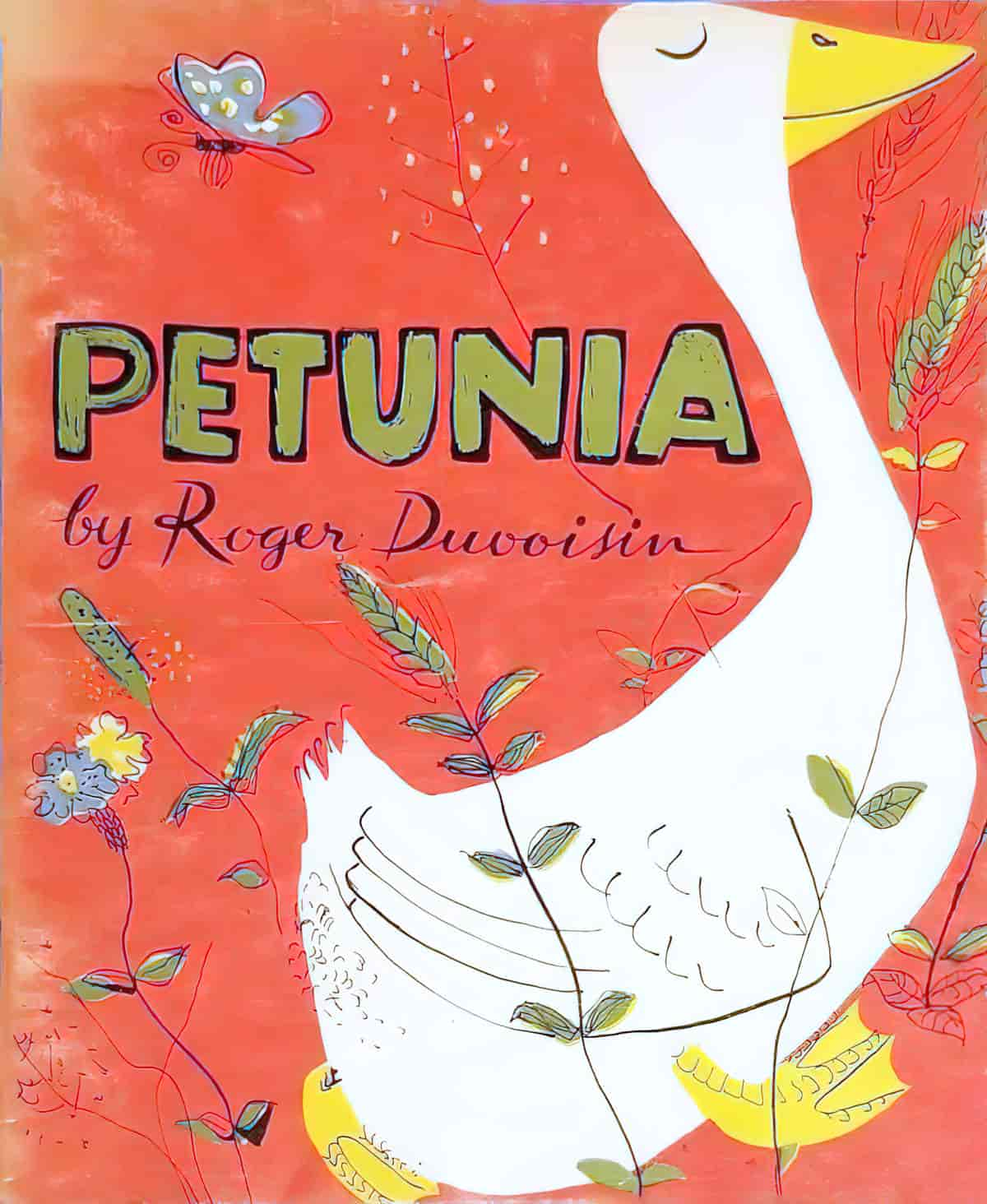

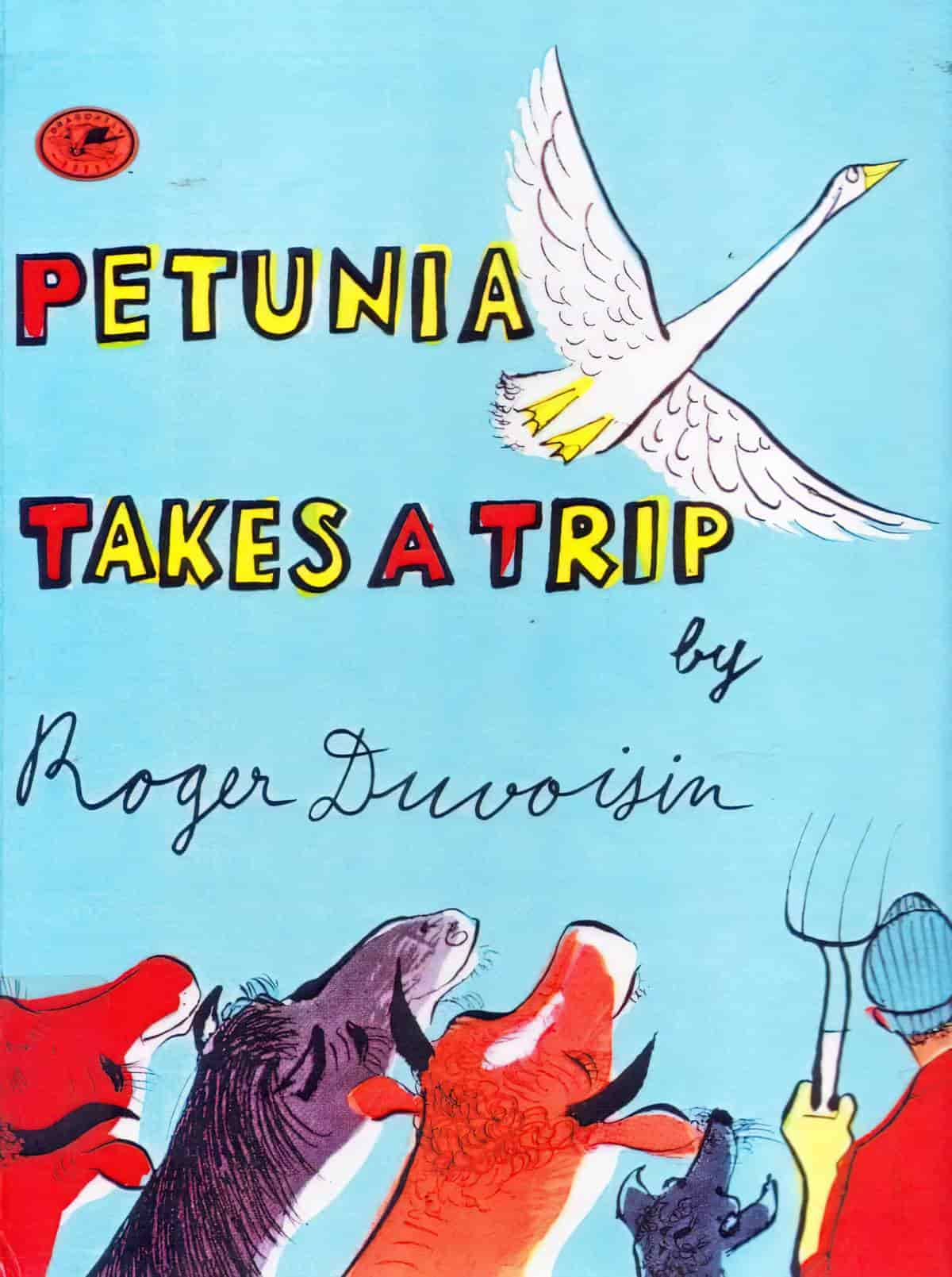

I’m a big fan of Roger Duvoisin (1904-1980), an American illustrator remembered mostly for his picture books. He also did magazine covers.

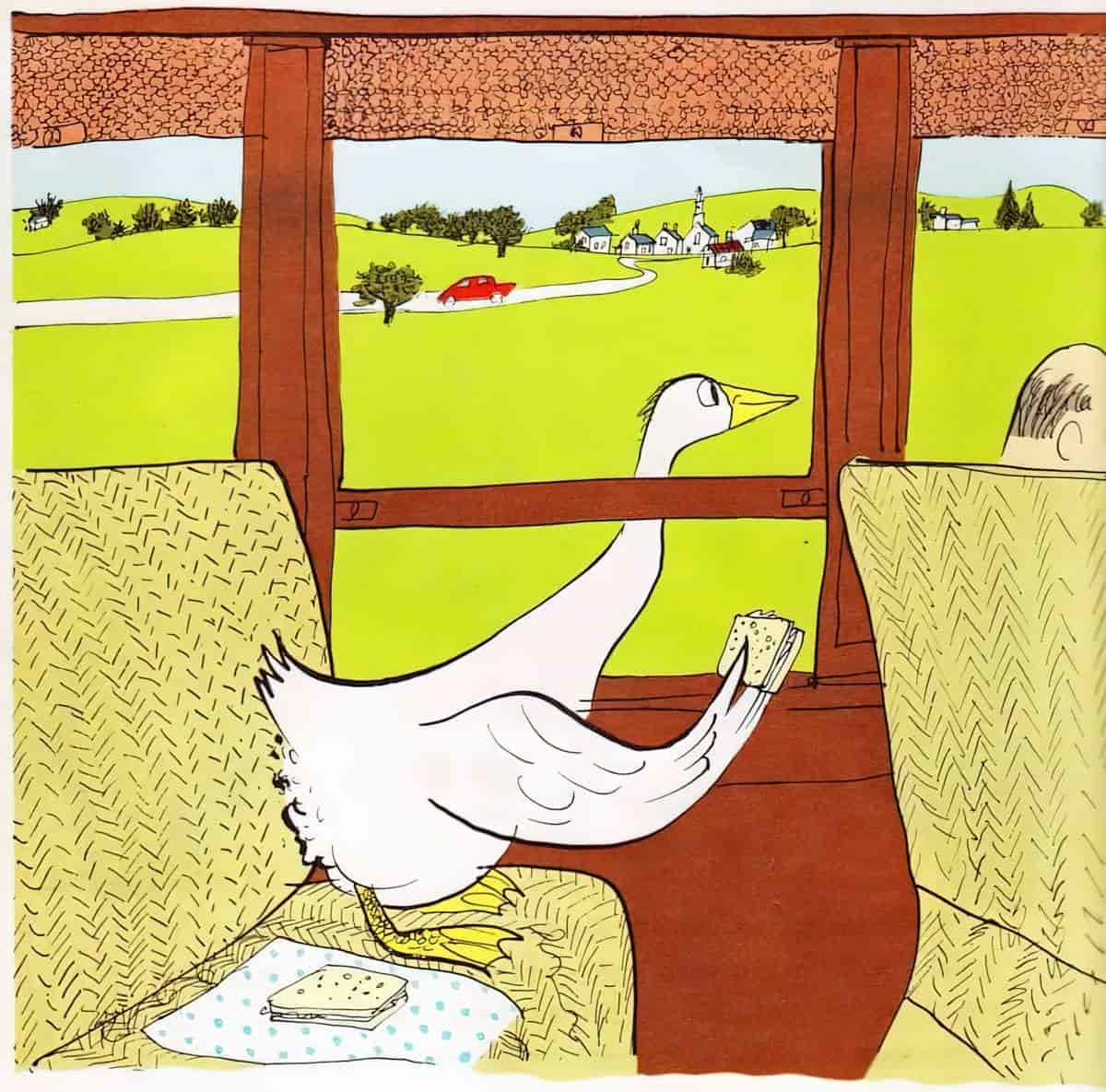

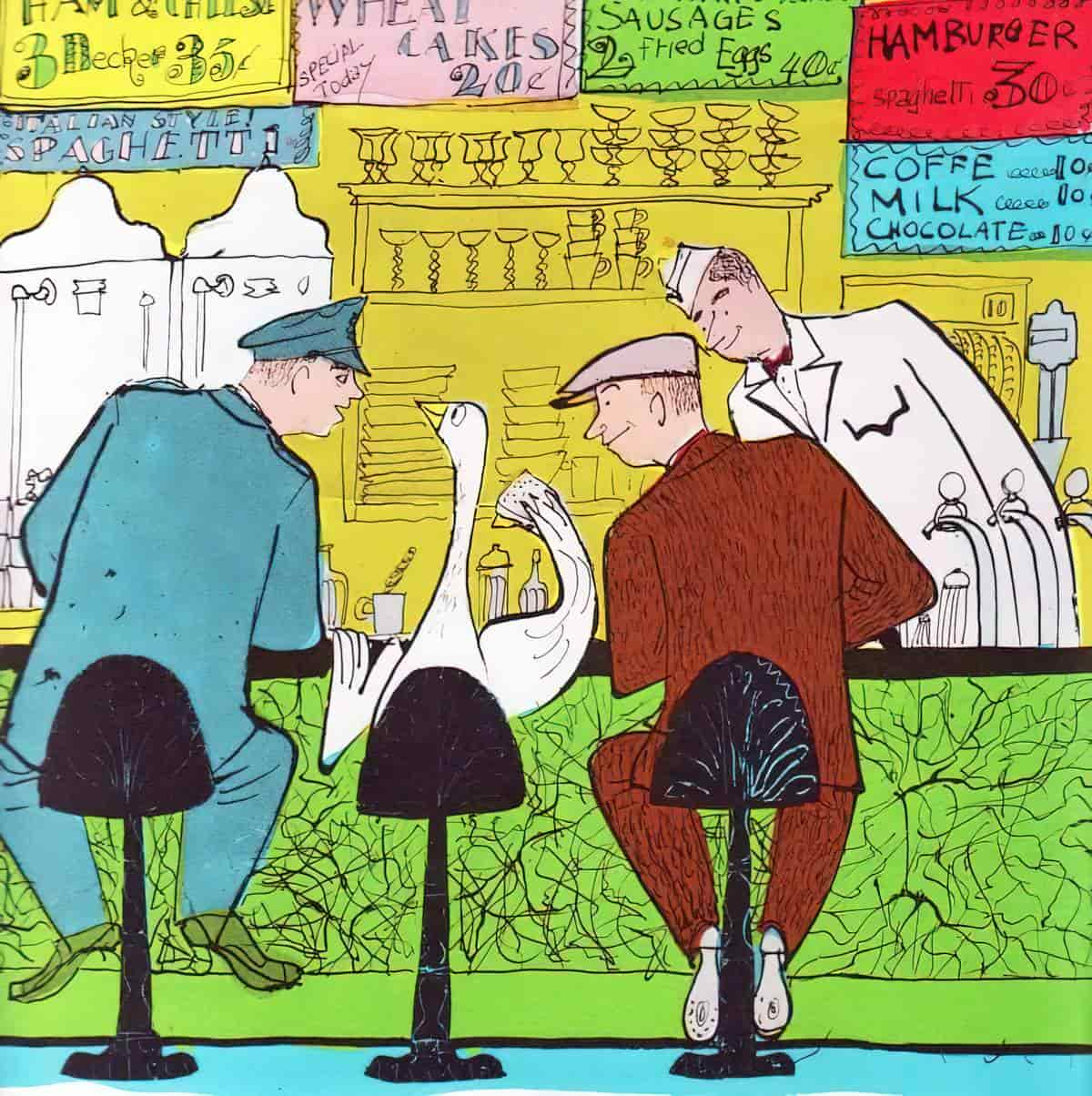

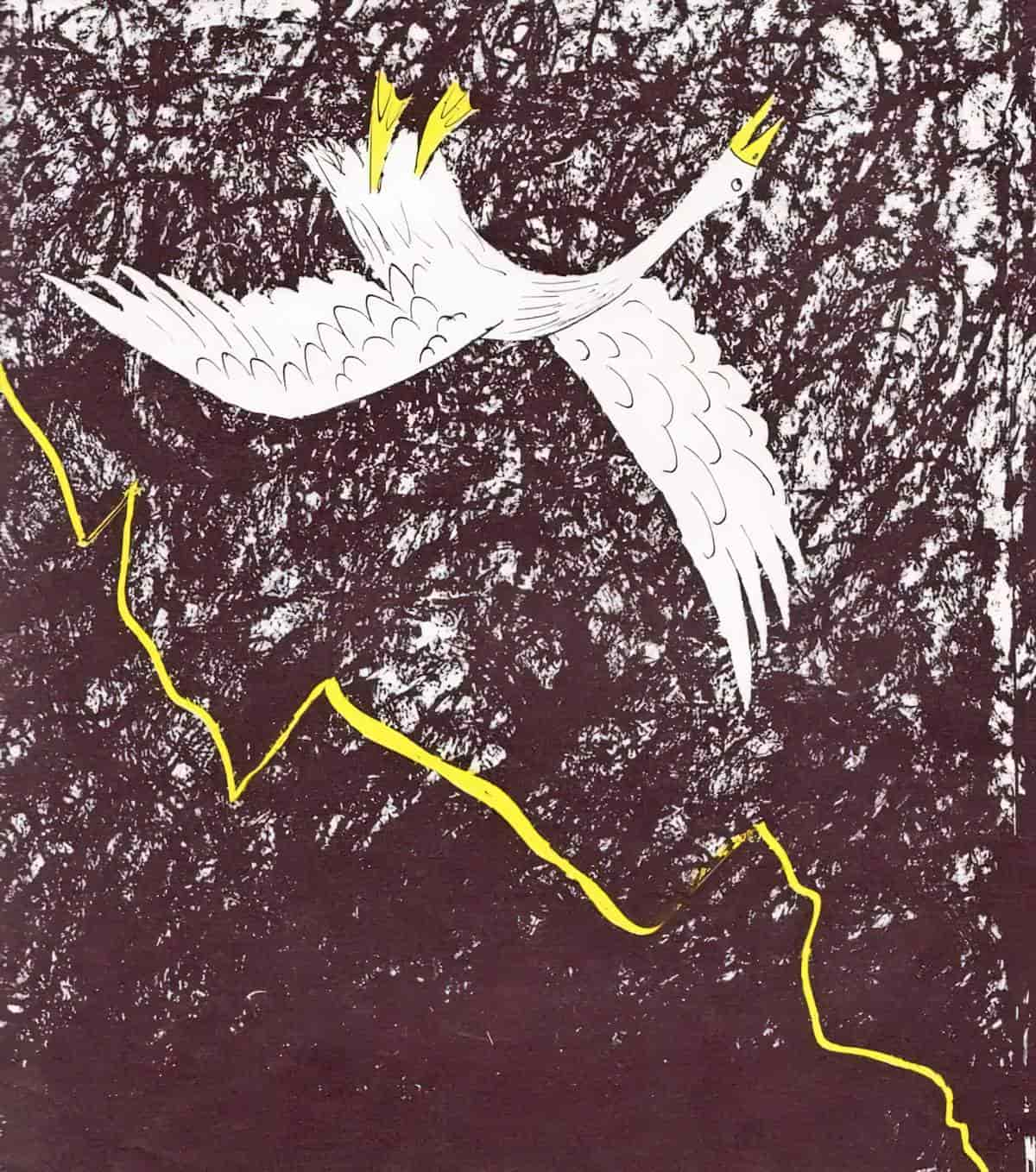

Duvoisin’s style is characterized by a playful use of colour and bold lines. He often used anthropomorphic animals as characters, depicting them in human-like situations. Duvoisin’s illustrations have a strong sense of movement. His “Petunia” series was especially popular.

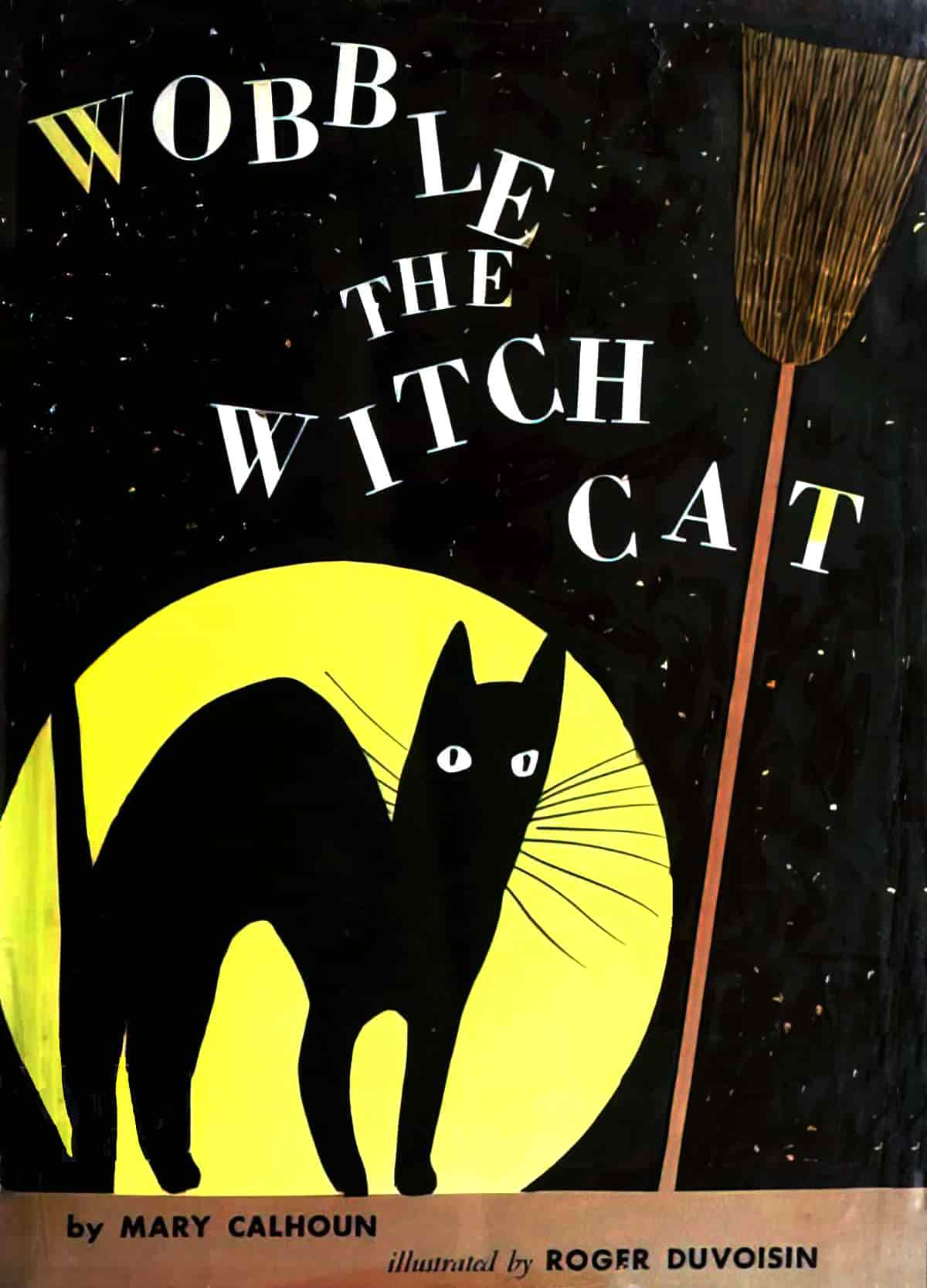

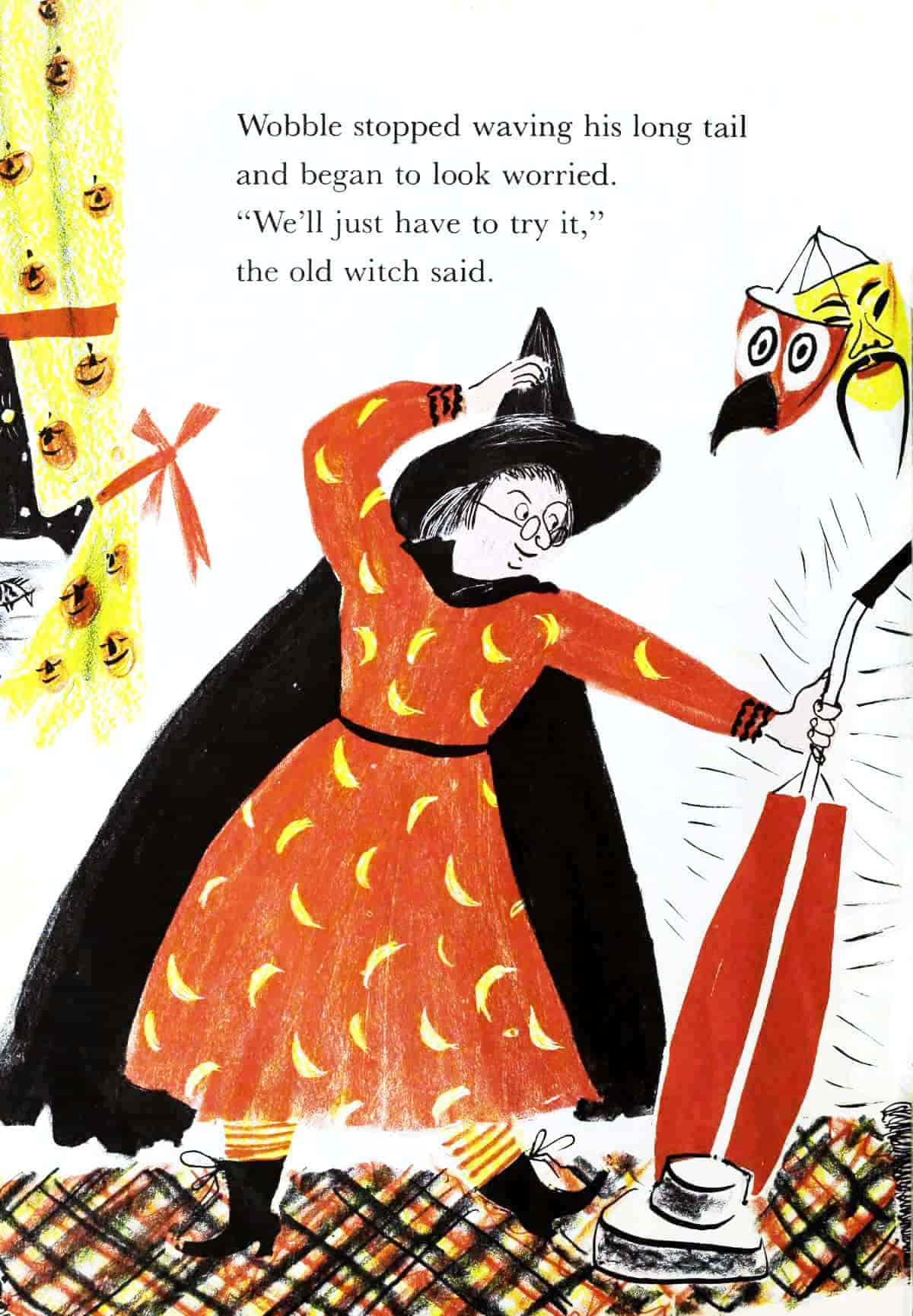

While looking for more of Roger Duvoisin’s work, I came across a 1958 picture book called Wobble, The Witch Cat written by Mary Calhoun who wrote middle grade and picture books, frequently starring witches, girls and cats.

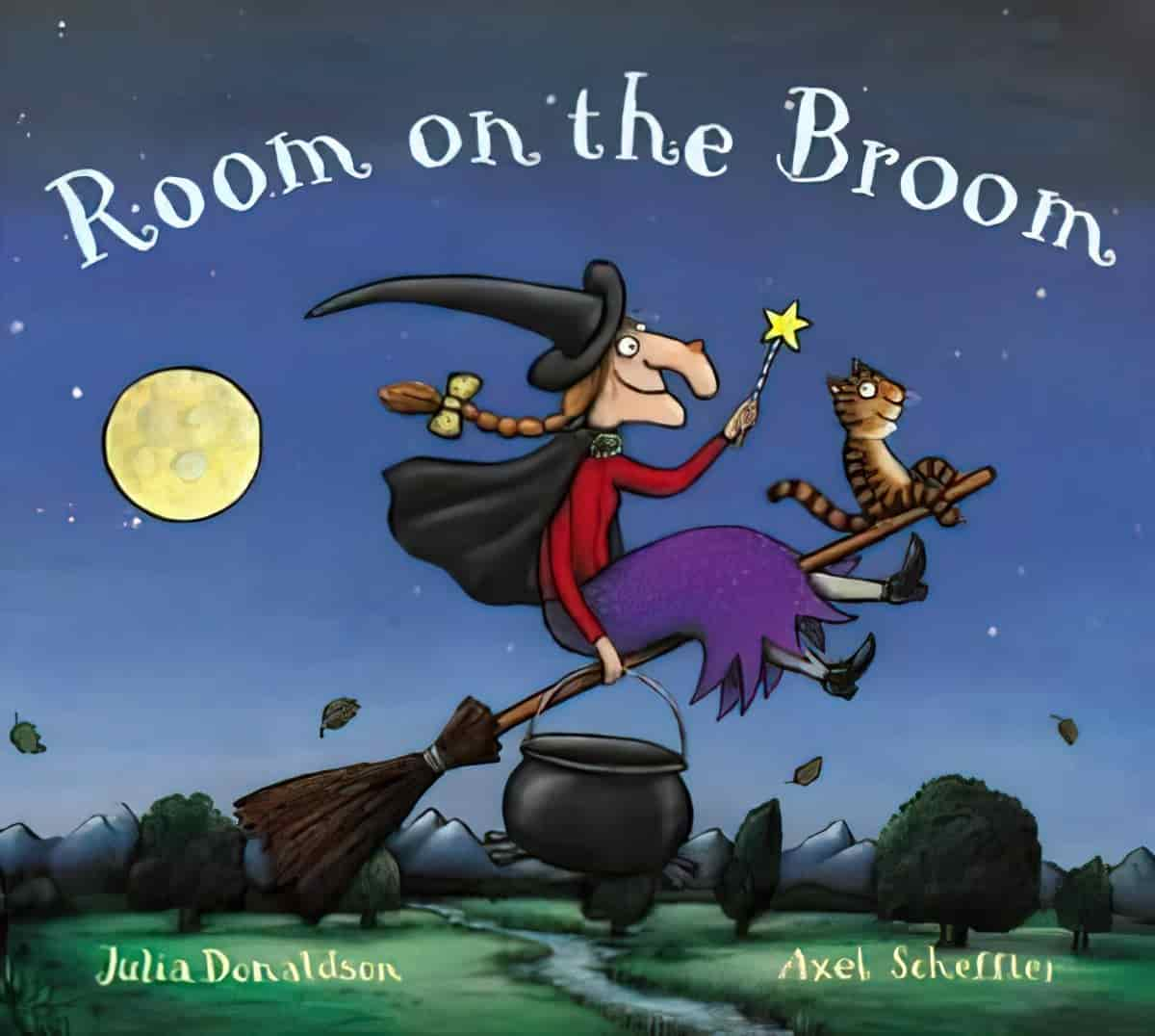

Wobble, The Witch Cat reminded me of a more recent picture book by Julia Donaldson, Room On The Broom. Both stories are about Good witches and their feline familiars. Both plots solve the practical issue around staying safe while zooming through the air on a broomstick. Any child who has taken a broom and tried to use it playfully as a witch has probably thought, “I’m not entirely convinced I could stay on this thing if it really could fly. Also, my fanny hurts.”

Room On The Broom is now over twenty years old and is no longer contemporary, but because of the similarities in plot, I’ll use Julia Donaldson (and Axel Scheffler’s) book to illuminate how — exactly — Mary Calhoun (and Roger Duvoisin’s) popular American picture book from the mid 20th century feels like a book from an earlier era.

Where to find these stories

WOBBLE THE WITCH CAT

Wobble The Witch Cat by Mary Calhoun and Roger Duvoisin is available on one hour loan from The Internet Archive (for free). If no one else is waiting for it, you can borrow a digitized online book for as many hours as you need.

Getting started at The Internet Archive

ROOM ON THE BROOM

Of course, Julia Donaldson’s picture books are held by any library in the English speaking world, and occupy face-out position in any chain store book section. There are various read-alouds, easily found on YouTube.

The 2014 short film adaptation was nominated for an Oscar. As one of the directors explains, “the story is about a witch and her animals on a broom, but is really about a family growing in size and how you as a person adjust to that… It’s important that no one gets left behind and I think you can really learn that from [this story].” The other director says the story is about becoming tolerant of difference.

As we shall see, that’s not the message in Wobble, the Witch Cat. The message in the older book is this: Your mum isn’t going to care if you’re uncomfortable. Sort it out yourself, resort to sneaky, vengeful tactics and hope for the best.

Room on the Broom by Julia Donaldson, illustrated by Axel Scheffler (2001)

The witch and her cat fly happily over forests, rivers and mountains on their broomstick until a stormy wind blows away the witch’s hat, bow and wand. Luckily, there are plenty of friends around to help her out, and they all want a ride on the broom too. It’s a case of the more, the merrier, but the broomstick isn’t used to such a heavy load and it’s not long before . . . SNAP! It breaks in two! And with a greedy dragon looking for a snack, the witch’s animal friends had better think fast!

back cover copy

A note on rhyming picture books: Literary agents frequently say they’re not looking for rhyme. Apparently this is because they see far too much poorly executed rhyme. Some will tell you that rhyme is old-fashioned. An additional, related problem: Rhyme (or more accurately, rhythm) loses some of its punch when performed by speakers of different dialects.

What, then, are we to make of the uber-success of authors like Julia Donaldson, or New Zealand’s Lynley Dodd for that matter, who only write rhyme, who are widely beloved and whose picture books are enduring bestsellers?

First, you really do have to be top of your game if you’re going to write rhyming picture books. Skill aside, there are financial considerations. When Julia Donaldson’s first (rhyming) picture book A Squash and a Squeeze was acquired, Donaldson explained years later during an interview: “In order for a picture book to be profitable, you more or less have to glue some foreign editions on, so you can do a bigger print run.” Donaldson was explaining how difficult it was to get her first book published at the age of 44.

Note that Donaldson had a long career of rhyming (in song and performance) before entering the publishing world.

Wobble, The Witch Cat by Mary Calhoun, illustrated by Roger Duvoisin (1958)

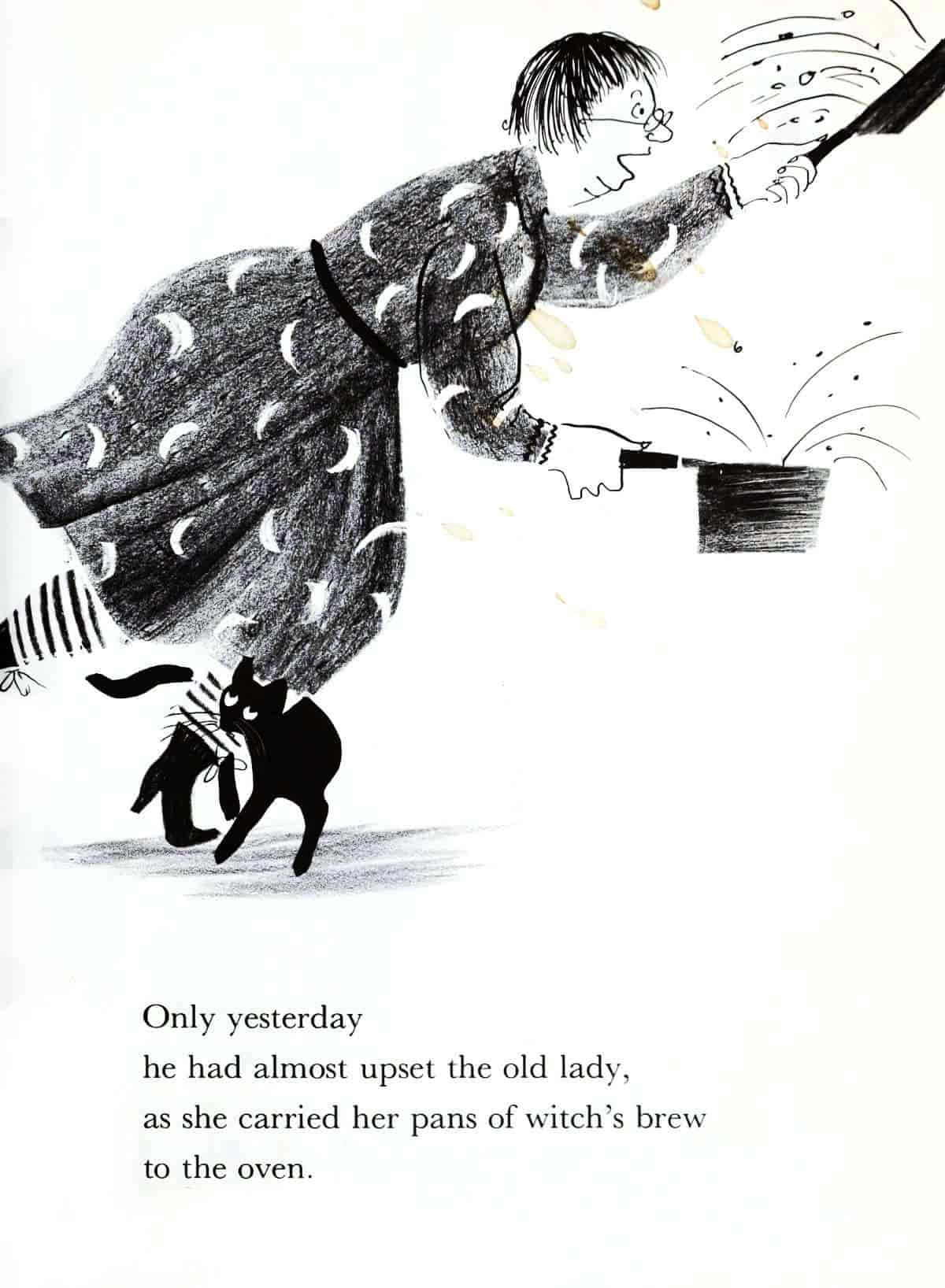

What could be worse than a witch cat who couldn’t ride on a broomstick? Wobble had been a very nice witch cat until Maggie, his fat chuckling witch, got a new broomstick. It had a thin, slippery handle, and when Wobble found he couldn’t ride it, his personality suddenly changed. Now he was as cross as he was black.

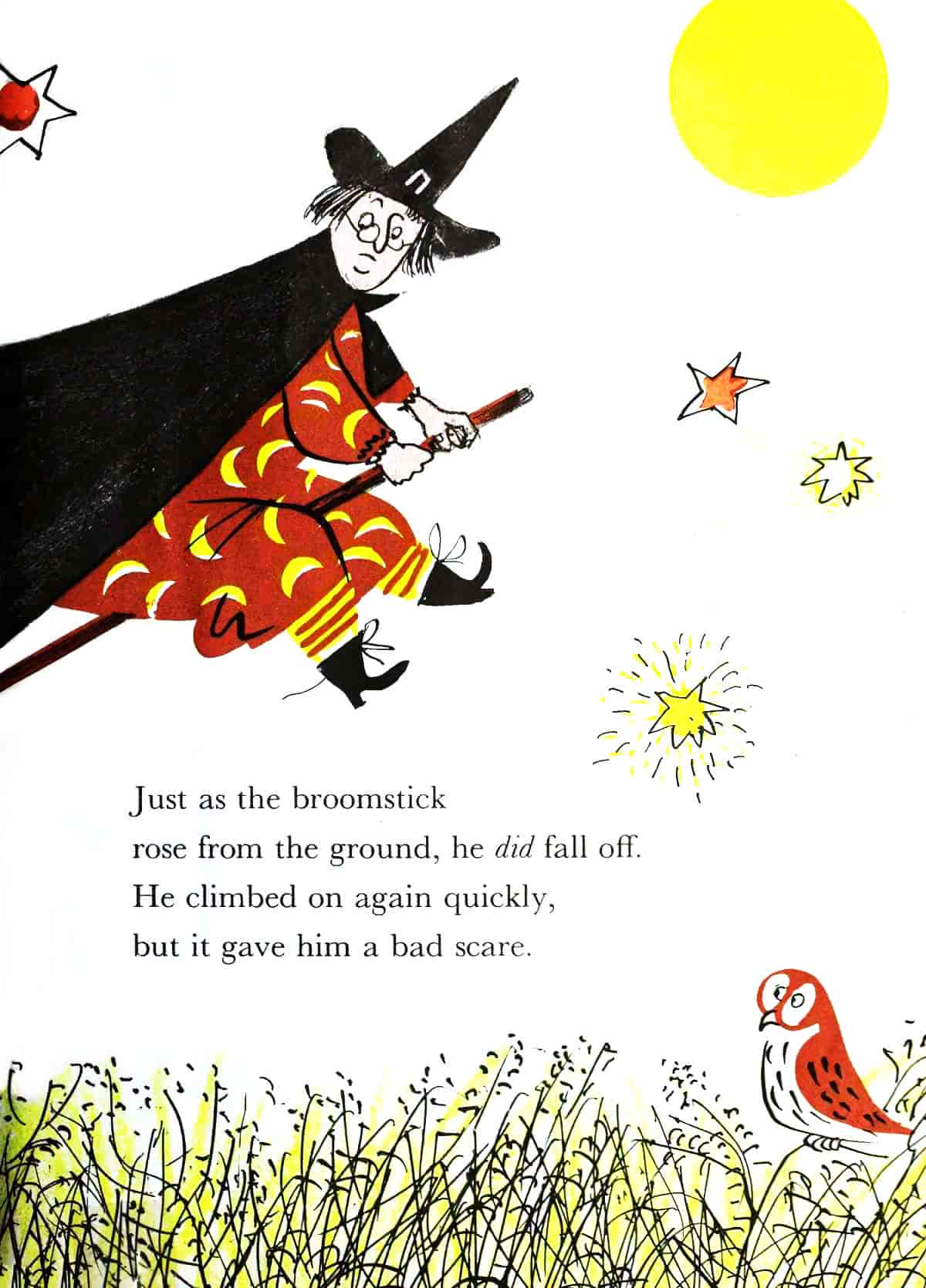

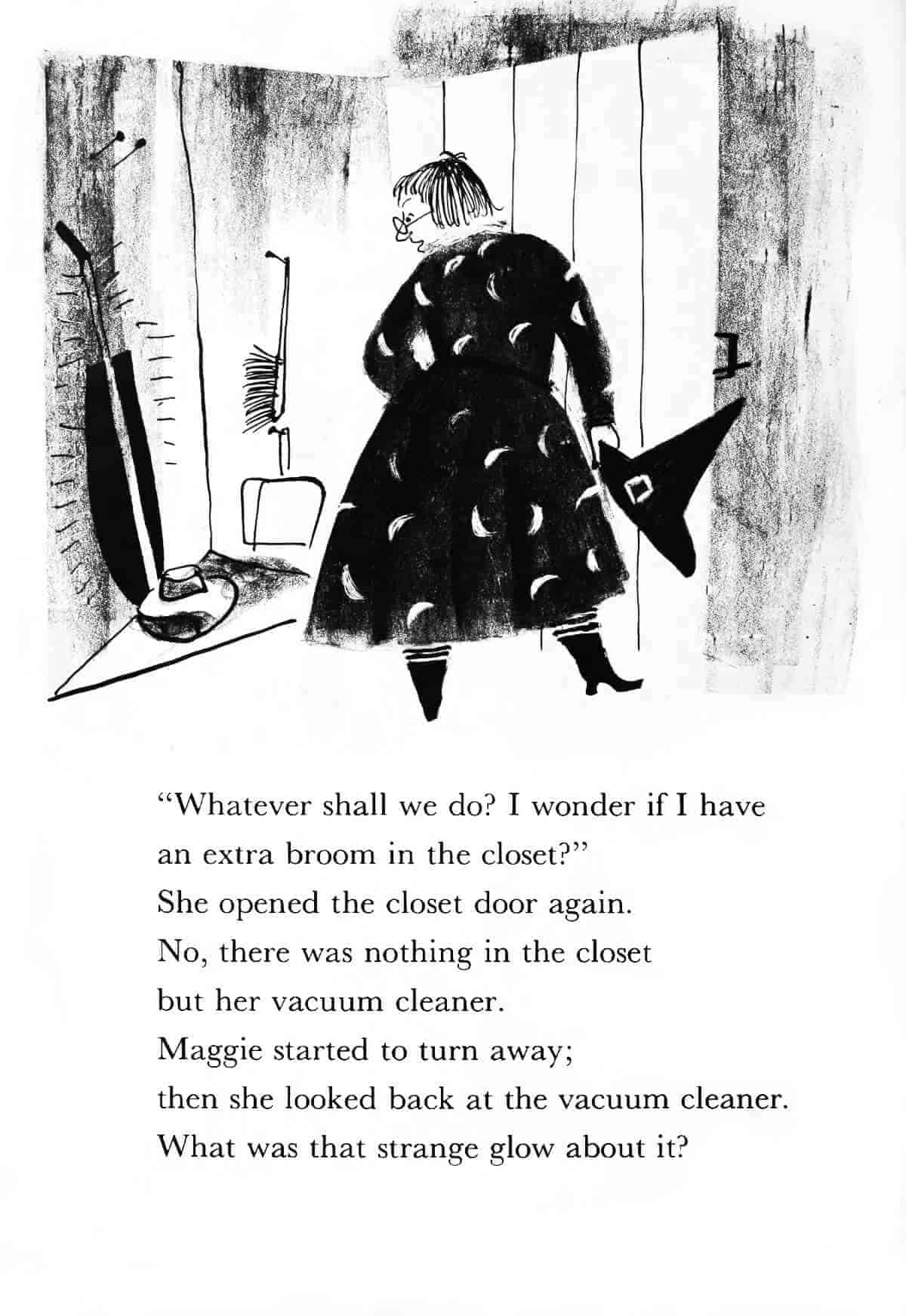

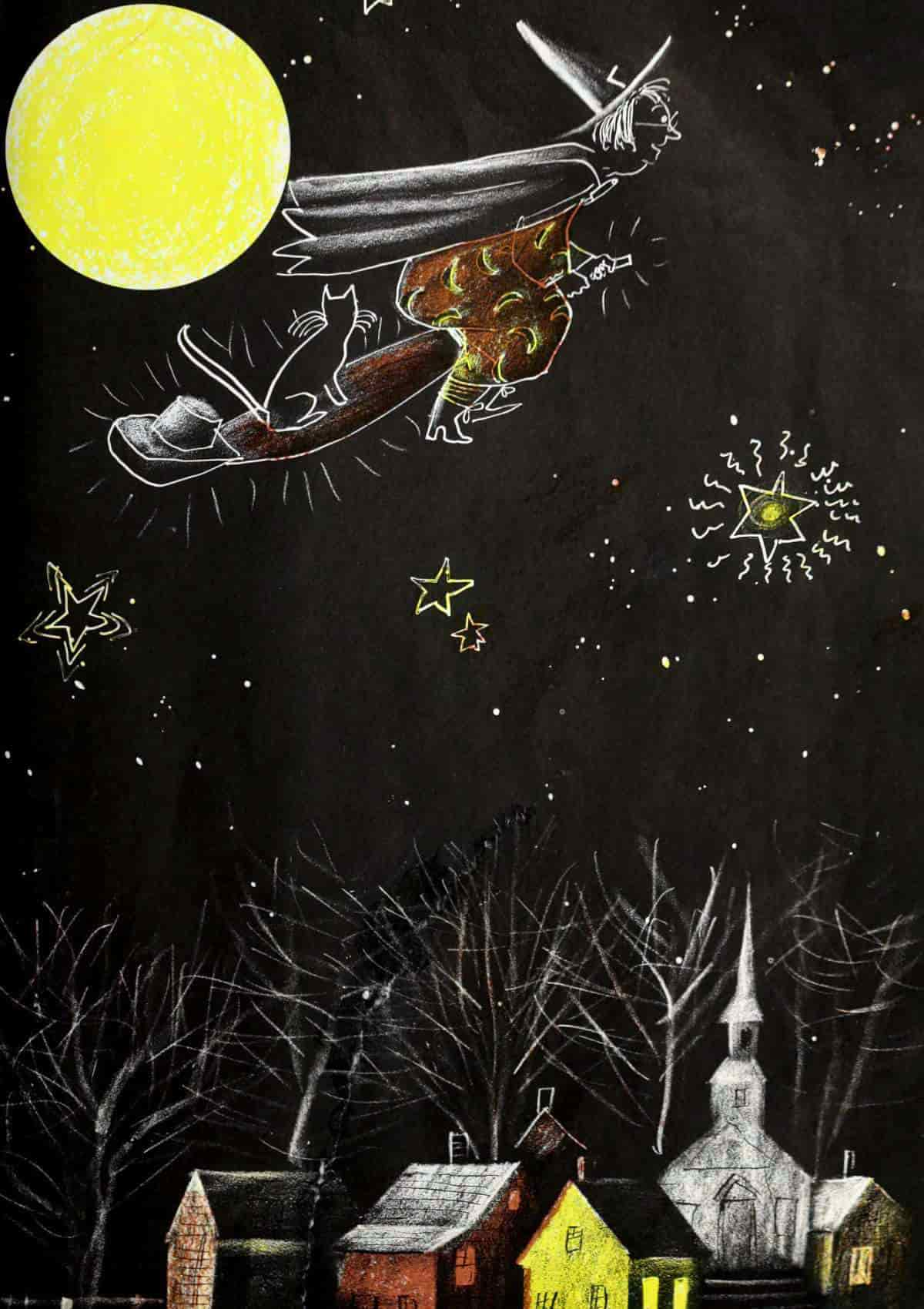

Finally Wobble, that unhappy cat, actually pulled the broomstick out to the trash barrel and thought his problems were solved. But Maggie found that her old vacuum cleaner also had flying magic, so she made her annual Halloween flight with her cat after all. What Wobble discovered and what the children saw in the sky that night combine to make a surprising climax.

Mr. Duvoisin is just the right illustrator for this hilarious tale, and his pictures of cross black Wobble and motherly Maggie make them come alive in a delightfully fantastic fashion.

flap copy

Whereas Julia Donaldson’s story has the modern theme of taking other people’s differences into account when making big decisions, Wobble, The Witch Cat conveys almost the opposite message. Wobble’s witch is completely oblivious to her cat’s predicament. She continues to use the unsuitable broom despite his discomfort, and the cat had better learn to deal, or else find a solution on his own.

Perhaps these stories reflect how family dynamics have changed in the last 70 years. Parents now make big life decisions while accounting for the happiness and comfort of their children. Where resources allow, many children now have some say on what to eat for dinner, where to go on holiday, what colour to paint their room, whether or not to relocate/change schools. Individual parenting styles differ, but even as late as the 1980s, I had no say in any of these things. Like it or lump it. Eat what’s served or go to bed hungry. This family dynamic was typical of the 20th century.

THE MARKETING COPY

The marketing copy of Wobble, the Witch Cat is almost as long as some contemporary children’s picture books today. It also seems aimed at adults without borrowing the voice of the text itself. Contrast with Room On The Broom, which utilises onomatopoeia and exclamation marks, suggesting something of the style.

MORAL TELLING

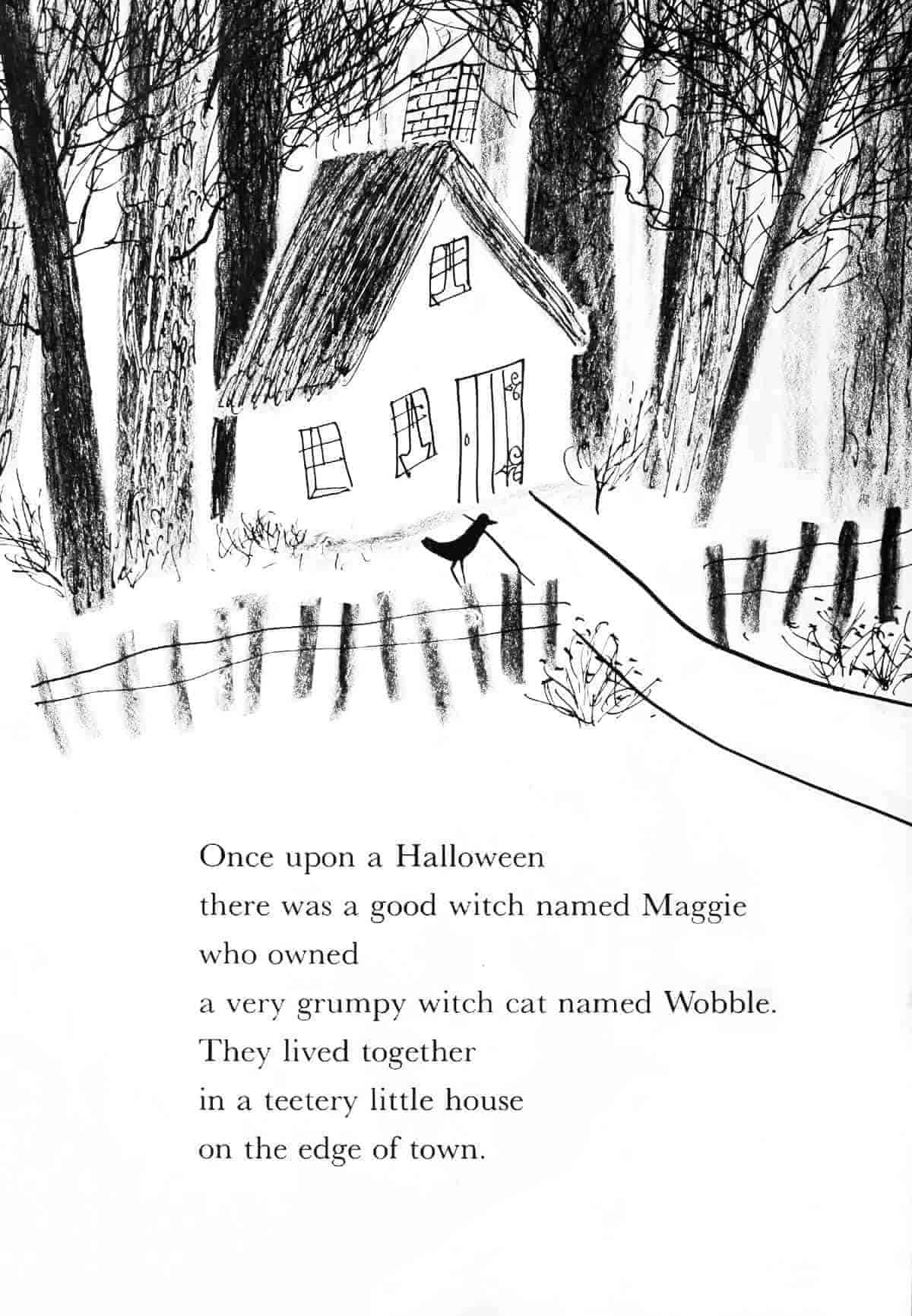

Wobble, the Witch Cat opens with:

Once upon a Halloween there was a good witch named Maggie who owned a very grumpy witch cat named Wobble. They lived together in a teetery little house on the edge of town.

There’s less tolerance now for a stated binary division between Good and Bad. Young readers definitely know who the Goodies vs Baddies are. We can’t shuck binary divisions off entirely, at least not until readers are developmentally ready to hear it.

In Room On The Broom, Donaldson clearly means us to empathise with the witch and wish for the defeat of the fire-breathing dragon. But to be told who is good and who is bad? That belongs in an earlier century. Even the youngest readers can be trusted to work that out for themselves.

In that lies another, deeper message: Decide for yourself who is Good and who is Bad. Don’t listen to what others tell you. Look at actions.

THE SWITCH FROM ITERATIVE TO SINGULATIVE TIME

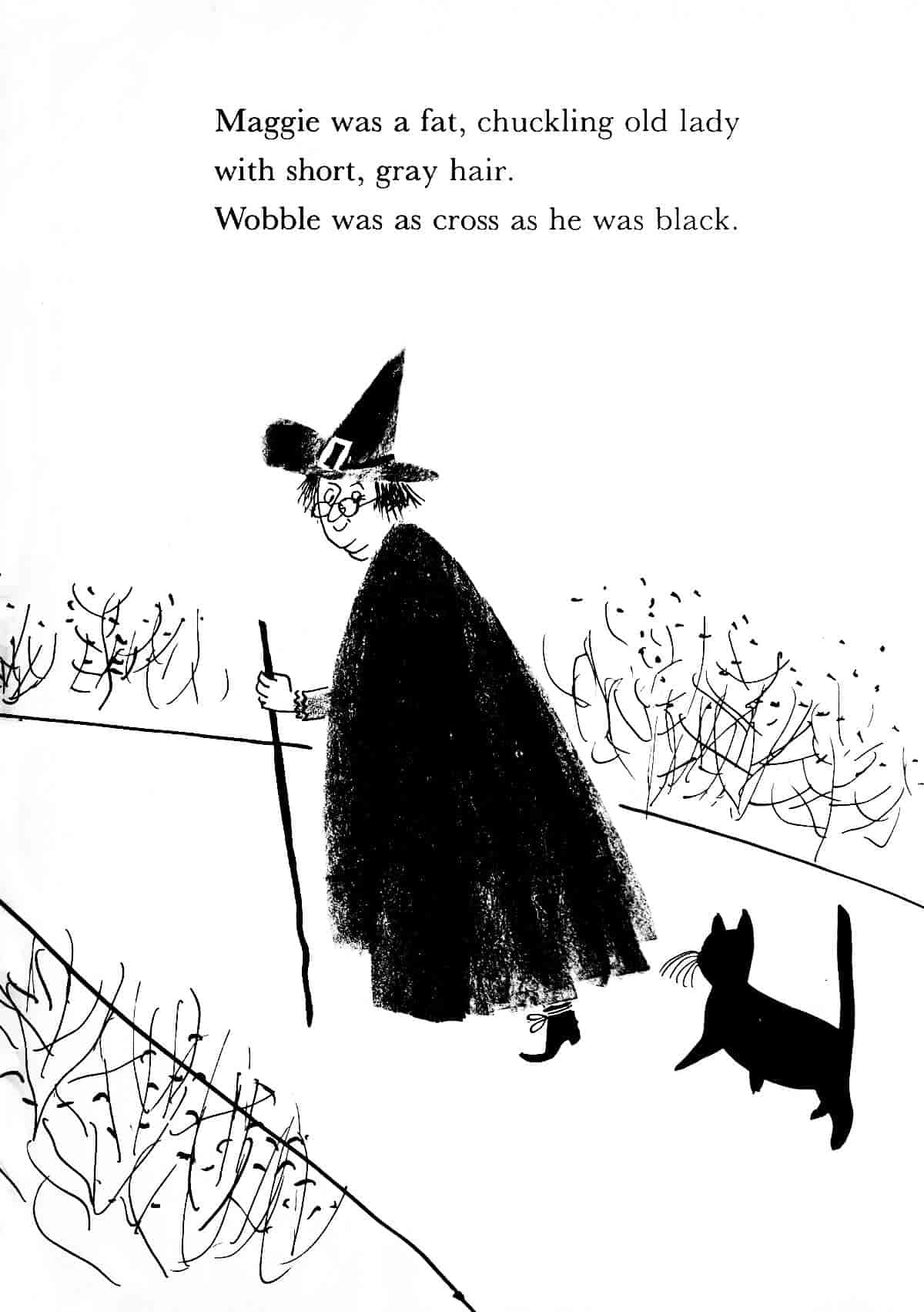

As apparent from Wobble, The Witch Cat, from an earlier Golden Age tend to start with a description of characters: Who they are, where they live, who’s the Goodie, who’s the Baddie… This section of the story has been called ‘the iterative’ treatment of time.

At some point, though, the story switches: Then, one day…

In picture books from earlier Golden Ages of Children’s Literature, the iterative, introductory part of the story runs much longer. In contemporary stories, it is often removed entirely. Therefore, if you start a picture book by telling readers all about the characters, the manuscript will read as old fashioned.

This change happened a good while ago. A stand-out example of a fresh voice was Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No-good, Very Bad Day (1972) by Judith Viorst, although if you read Viorst’s other work, it can feel long and drawn out by contemporary standards.

DIFFERENCE FOUR: BACKSTORY

He hadn't always been so cross. Once he had been just as good as Maggie. It was all the fault of a new broomstick that Maggie had gotten for the last Halloween.

THis is related to the previous point, because backstory happens during the iterative, introductory part of the story.

By contrast, in Room On The Broom, we are told nothing about the witch other than what we can see for ourselves: That she wears a tall hat and that she ties her hair up in a bow. (The hat and the bow become part of the plot.)

Donaldson’s witch arrives in statu nascendi (without backstory). We don’t know where she lives, what she does each morning before leaving on her broom, where she’s going… It doesn’t matter. Readers accept The Witch Archetype. Also, it’s up to us to work out whether she’s good or bad. That’s part of the suspense. For all we know, she’ll throw the cat off like a psychopath.

GENDER AND RACE

ANTI-BLACKNESS

Contemporary publishers are more mindful of associations between blackness and anti-Black racism.

WOMEN AND VACUUM CLEANERS

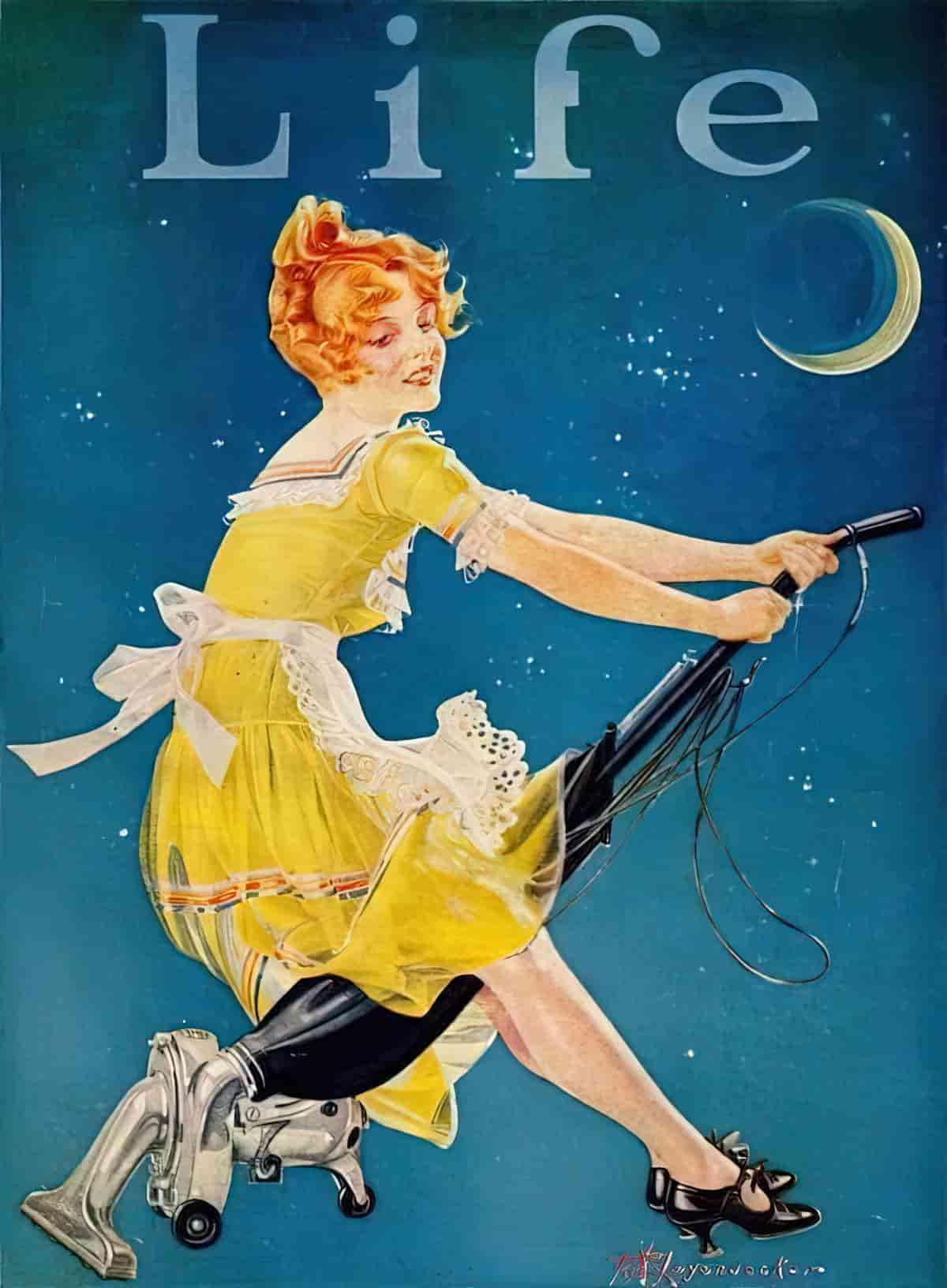

The vacuum cleaner in the closet aligns with the new cleaning technologies which started to become ubiquitous in middle-class homes around the time this book was published. The Modern Woman is the Modern Witch. The broom, too, was subverted by women themselves. Sure, they may be stuck inside the home, tied to the kitchen, cleaning, cooking and sewing from dusk til dawn, but imaginatively they could use the tool of their oppression and fly out the window.

Now vacuum cleaner manufacturers worked to persuade women to return to the house (after ‘helping out’ during the war) and this time their lives would be far better because, look! Look at these high-tech vacuum cleaners. Who wouldn’t want to stay in the home and clean all day?

See also: The Symbolism of Broomsticks

There’s a modern attempt to show fathers in picture books as more involved — with childcare mostly, but occasionally with cooking and very occasionally with housework. In fact, there’s a case to be made that there are now more “involved” fathers in picture books and middle grade novels than there are in real life. Mothers continue to be disproportionately backgrounded, at any rate.

EMOTIONAL DISTANCE BETWEEN PARENT AND CHILD

In Mary Calhoun’s book, the cat is the ‘child’, the witch is the ‘mother’. Throughout Wobble, the Witch Cat we see a parental figure who is completely oblivious to the suffering of her own dear cat. Instead, the story itself criticises Wobble for having vengeful thoughts about her.

Wobble arranges to trip the witch over. We’ve got Chekhov’s knife right there on the page, and we know it’s not there for carving pumpkins…

…because the recto side of the double spread is this:

At no point does the witch realise how much discomfort she’s been doling out to her cat due to her selfish decision to buy a skinny new broom. Instead, it’s up to Wobble, alone, to take their broomstick from the closet and put it in the trash. (This is also the solution of Harry The Dirty Dog who tries to hide the scrubbing brush because he hates baths. Harry stupidly puts the brush under his own bed. But cats are smart, see. They put the cursed thing in the trash… then make sure the garbo comes to collect it.)

Wobble is none too happy when the witch decides to make use of the vacuum cleaner instead.

But it just so happens the vacuum cleaner features a soft, cushiony spot which is perfect for a cat to ride on in comfort. We can assume cat and witch are no closer than they were before. There remains an emotional divide between caregiver and child, which is probably an accurate experience of childhood for twentieth century children.

BULLYING

We are told that Wobble is bullied and jeered at for failing to stay on his witch’s broomstick. As we know from Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer, there’s nothing to be done in a 20th century bullying situation but improve yourself (or your situation) until the bullying stops.

We have higher expectations of depictions of bullying in contemporary stories: Bullying is a social system, and it’s not up to the victim of bullying to change themselves until the others stop.

There’s no bullying in Julia Donaldson’s Room On The Broom. Instead, the fire-breathing dragon is a Minotaur opponent who is cowed when he (or she) realises he’s met his match. The message is a contemporary one about the power of family or the solidarity of found family: Band together and you can overcome whatever bad thing comes to you.

BOOKENDED WITH ‘REAL CHILDREN’

As Wobble and his witch fly through the air, children out on Halloween look up and see a speck in the sky. In this way, Calhoun brings the story into the real worlds of (American) readers who themselves may be preparing for a trick-or-treat adventure.

This technique is also a little meta — by bringing ‘real children’ into the story, readers are reminded that they, too, are watching a spectacle and the spectacle is a story. The metafictive aspect is reassuring: There’s no such thing as witches. This is just a story, but believe it if you want to!

Metafiction is also a feature of Postmodern picture books as it plays with framing. Postmodern picture books took off later in the century and contemporary picturebook authors and illustrators have done many interesting things with the picturebook form.

MORE BOOKS BY MARY CALHOUN