The word ‘hermeneutical’ comes from the Greek word for ‘interpreter’ and means ‘pertaining to interpretation’. Every member of an audience interprets a text differently, depending on the life experience they bring.

If you’re like me and you keep hearing this word and also keep forgetting what it means, a fix for that to simply replace ‘hermeneutics’ for ‘interpretation’.

If you’re reading about literature and literacy, this works just fine a lot of the time.

To get fancy about it, hermeneutics involves looking at the separate parts in order to understand the whole.

HERMENEUTICS AND THE FIELD OF LITERATURE

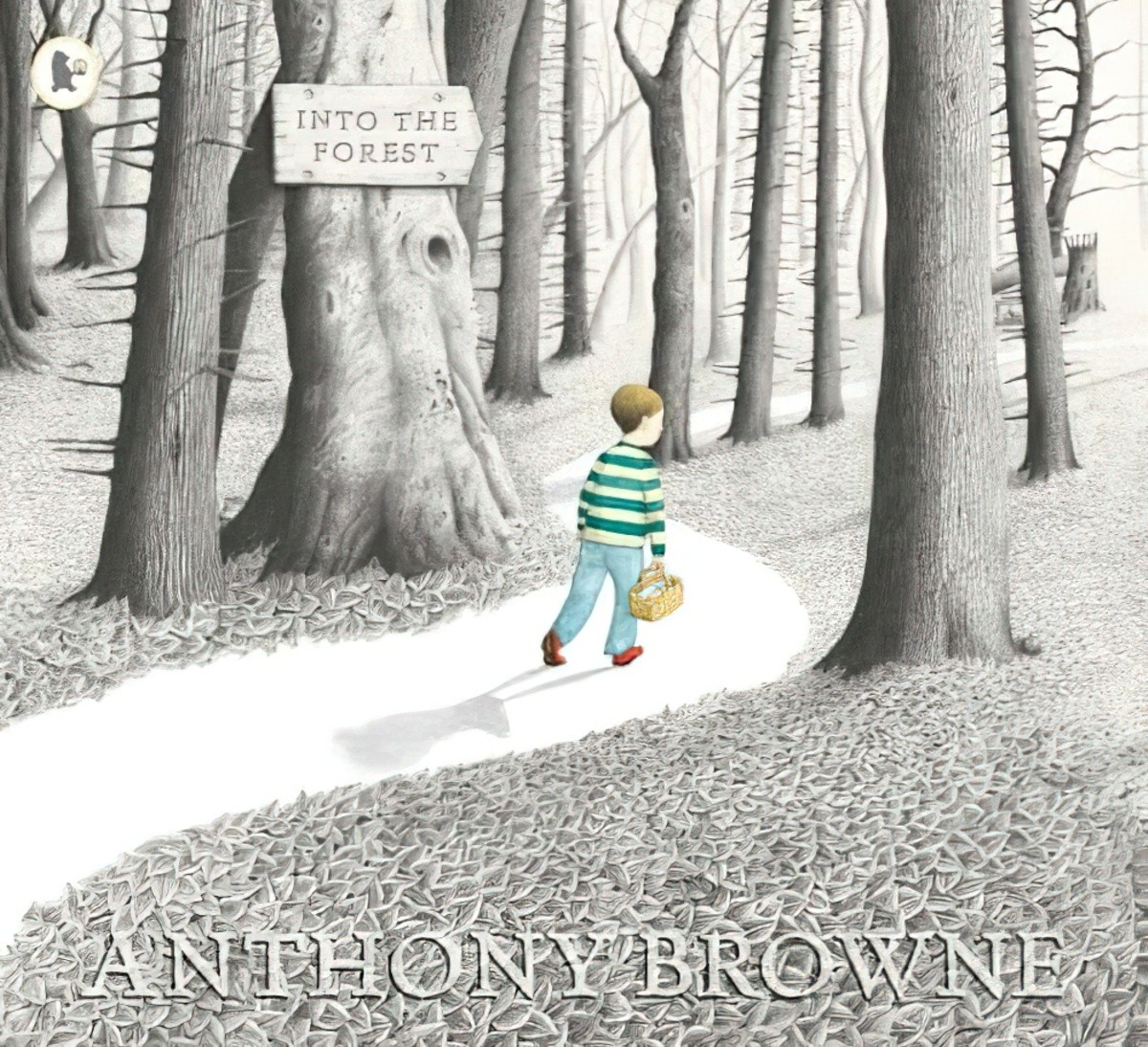

A hermeneutical reading requires we look at the forest, then at the trees, then again at the forest:

The theory about interpretation of texts is called hermeneutics. The word alludes to the name of the Greek god Hermes who was the messenger between gods. Hermeneutics thus emphasizes that a message needs someone to carry it, someone to explicate, to elucidate, to interpret. A hermeneutic analysis involves pointing out and explaining how what we read or otherwise perceive embodies a meaning. The main premise of hermeneutics is that in extracting a meaning from a piece of art we alternate between the whole and the details.

For instance, when we look at a painting, we can start by perceiving it as a whole, noting the general composition, theme, colour scheme, and so on. Provided that we are interested enough in learning more about the painting, we may then study the details, for instance each depicted object, figure, or shape; the foreground and the background; the particulars of hues and saturation; the individual brushstrokes (or other technique); and so on. However, if we stop at this stage, our perception of the word will be fragmentary. Therefore we must go back to studying the whole, this time with a better preconception, since we know more about the constituent parts of the whole.

In studying a literary text, we also usually begin with the whole: the storyline, the central characters, and their role in the story. When reading for pleasure, we often stop at that. Working with the text professionally, as critics or teachers, we will most probably go on to study the details: composition, characterisation, narrative perspective, style and underlying messages. We may go still further into particulars, for instance, and only examine metaphors, or only concentrate on direct speech, or only investigate how female characters are portrayed. Such a detailed study is, however, only fruitful if we afterward go back to the whole, and hopefully we will then have a better understanding of the text.

Aesthetic Approaches to Children’s Literature: An Introduction, by Maria Nikolajeva

THE HERMENEUTIC CIRCLE OF READING

Why do children read the same book over and over? No, it’s not to torture parents and teachers! Here are some pedagogical and developmental reasons why. It’s to do with the concept of ‘hermeneutic reading’.

1. COMFORT

There is great comfort in the predictable, especially before bed or when other things in life are changing.

2. TO GAIN BETTER UNDERSTANDING OF THE TEXT

At some point many readers must realise that there are far too many books in the world to continue reading the same ones over and over (although I do know middle-aged Tolkien enthusiasts who read Lord Of The Rings every single year). Children who ask for the same story over and over are often getting more out of it each time. This experience is especially valuable when adult input happens during some of the readings. (Story book apps with auto-narration are especially useful in this repetitive process, because adults have a smaller tolerance for repetition than their children.)

CAN WE INTERPRET A TEXT IN ANY WAY WE LIKE?

I can use anything I want to evaluate a work of art – the biography of the author, the opinion of popular people in my social circle, a dream I had last night

Arthur Chu, 11:15 AM · Aug 1, 2021

Beware of books. They are more than innocent assemblages of paper and ink and string and glue. If they are any good, they have the spirit of the author within.

Erica Jong

When people say ‘There’s no wrong way to read a book’, this is what they’re talking about. Yes, you may interpret (headcanon) a text in any way that you like.

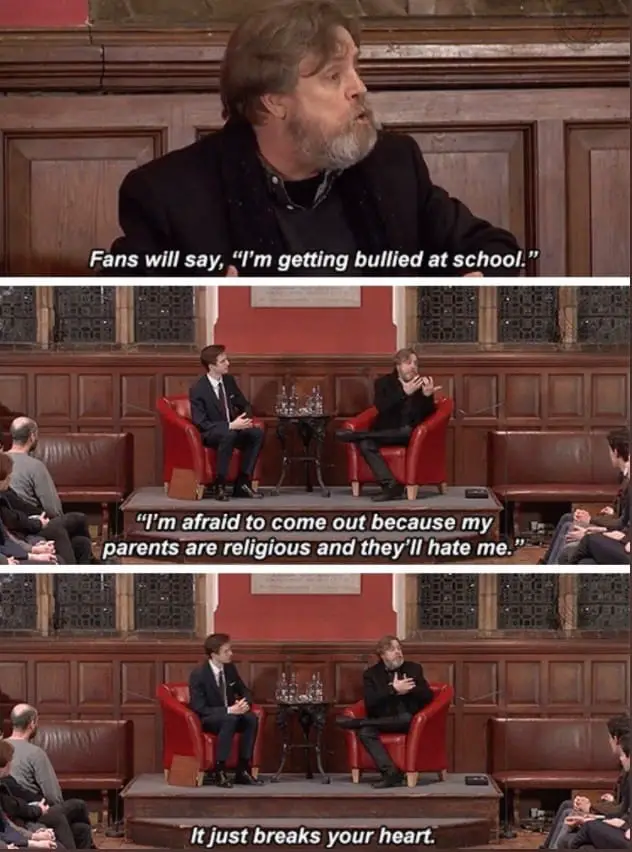

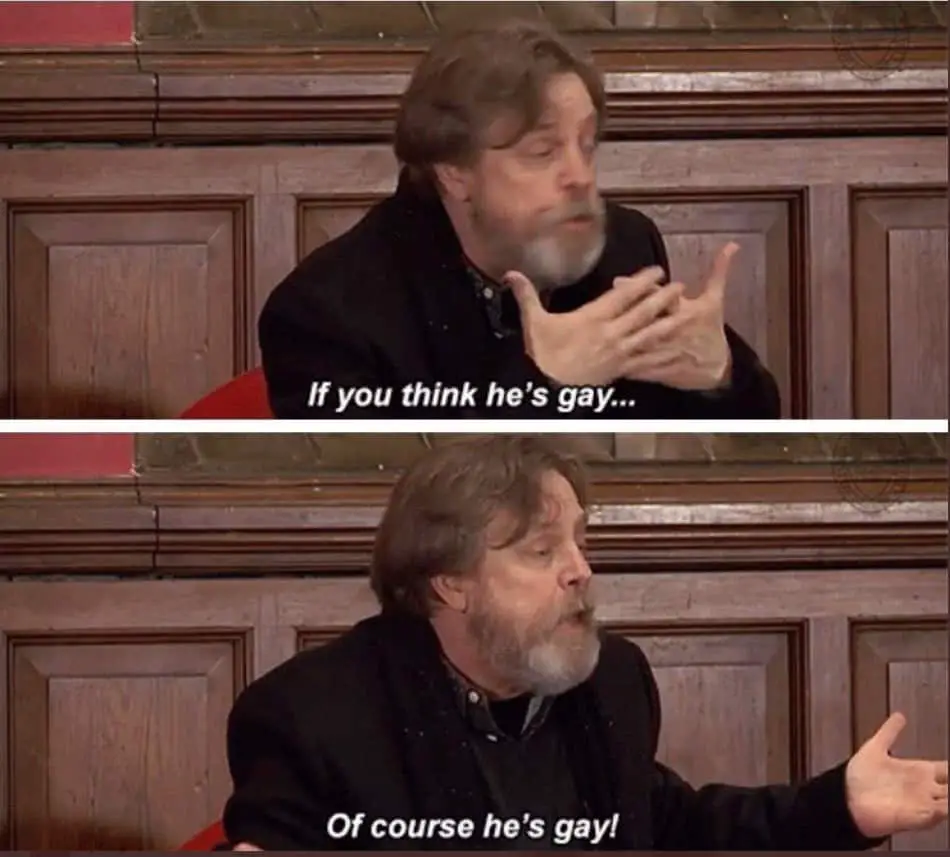

Mark Hamill is responding to attitudes such as that offered by Anthony Mackie, a Marvel actor:

It used to be guys can be friends, we can hang out, and it was cool…You can’t do that anymore, because something as pure and beautiful as homosexuality has been exploited by people who are trying to rationalize themselves.

Anthony Mackie on His ‘Promotion’ to Captain America, and Sam and Bucky’s ‘Bromance’ on ‘Falcon and Winter Soldier’, Variety

Mark Hamill speaks to his audience in layman’s terms about how audiences interpret a text, independent of any inherent qualities, or functions, in the text itself.

I increasingly think “explicit” queer representation has less value than metaphorical queer representation. […] Explicit queer representation is a trap. It too easily makes queerness a fixed constant — you figure yourself out, and there you are.

But the whole concept of our identities is a kind of fluid, malleable understanding of the self.

Again: This has value! Telling kids, for instance, that there is nothing wrong with being trans is useful! I’m just not sure how useful it is to reduce the idea of queer representation to “This character is trans, and that reflects our growing acceptance in society! Yay!”

I am MUCH more likely to see myself via METAPHORICAL queer representation.

@emilyvdw on Twitter

Emily VanDerWerff then offers as an example Midsommar, a horror film which has “a deeply trans narrative hiding in plain sight.“

Here’s an academic way of saying that a text is nothing without its audience:

Texts have no inherent function(s), but they are usually intended for a function or set of functions by the author or sender. In the act of reception, the recipients decide which function(s) the text has for them. This means that a text which has been intended for a particular function by its sender (in the light of his/her communicative situation) can be used for quite a different function by the recipients (in their own communicative situations, possibly distant in time, certainly in place, from that of the sender).

However, the recipient‟s decision is not absolutely arbitrary.

Text Functions In Translation Titles and Headings as a Case in Point

A note on that final sentence: If audiences interpret a text in a certain way, and that way promotes, say, bigotry, the text doesn’t get a free pass. Storytellers don’t get to lead audiences to certain conclusions (mindfully or accidentally) and then blame all bigoted interpretation on the audience.

For that, Breaking Bad is an excellent case study. A large proportion of the audience hated Skyler White. Vince Gilligan blamed the audience for this without looking at how he helped them along.

The paper on the text-functions of titles above reminds us that reception of a text is guided by:

- Pre-signals given by situational factors

- Structural features used as function-markers

- The recipient’s communicative necessities

- The recipient’s expectations vis-a-vis the text-in-situation, which are based on previous reading experience and (culture-specific) world knowledge.

HEMENEUTICS AND THE LAW

HERMENEUTICAL INJUSTICE

Knowledge is power. But what about people who don’t have certain knowledge?

Hermeneutical injustice is English philosopher Miranda Fricker’s term for the harm caused by being denied crucial information.

Hermeneutical injustice occurs when someone’s experiences are not well understood—by themselves or by others—because these experiences do not fit any concepts known to them (or known to others), due to the historic exclusion of some groups of people from activities, such as scholarship and journalism, that shape which concepts become well known.

from the Wikipedia article on Epistemic Injustice

Hermeneutical justice is a structural phenomenon. It is about marginalized groups lacking access to information essential to their understanding of themselves and their role in society—and these groups lack this information precisely because they are marginalized and their experiences rarely represented.

Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex by Angela Chen

- If I’d known about perinatal depression I’d have gone easier on myself.

- If I’d known my child was dyslexic I wouldn’t have got so frustrated with them (and myself) with the home readers

- If I’d known to separate romantic and sexual attraction maybe my former relationship could have worked out

- If I’d known I was autistic I could have asked for accommodations

- If I’d known what sexual assault looks like I could’ve acknowledged my own trauma

The SHIFT study found that students who experience assault–regardless of gender or sexual orientation–will, in conversations with peers, downgrade the incidents, labelling them “weird” or “awkward” or “regrettable” in order to keep the peace among friend groups or student organizations; for the sake of their own well-being; or because it doesn’t fit their self-image. That may be especially true for boys, who in both Jessie Ford’s interviews and the SHIFT research would make a joke out of unwanted sex, calling it “funny” or — here it is again — “hilarious”, especially if their friends had found out about it. […] “Men are supposed to be the aggressors and girls the blockers, so that makes it hard for men to understand and label their own experiences of unwanted sex. Agency and consent are assumed. It also makes it hard for women to understand the necessity of getting consent from men.”

Peggy Orenstein, Boys and Sex (2020) p193

- If I’d known that my poverty was the endpoint of a system which ‘requires people to administer their own poverty‘ I wouldn’t have blamed myself for not working hard enough

- (the list goes on and on)

The very fact that we even have a word for something provides an implicit signal that it is worth talking about. The effects of lacking words to describe one’s own experiences can be serious. For example, lacking a word like “polyamorous,” a polyamorous person can be left reaching for words that encode a negative judgment (such as “unfaithful”) or suggest a crime or sin (such as “adulterous”). Only being able to describe your intimate feelings by passing negative judgment on yourself has psychological consequences.

Carrie Jenkins, What Love Is And What It Could Be (2017) p39

I used to believe that rapes happened in dark alleys and parking garages. I thought they had to be physically violent, the man forcing your legs open. I was a child of the ’90s weaned on after-school specials and made-for-TV movies about innocent white girls losing their virtue at the hands of a psychopath. It was all “No means no!” I had never considered that rape could happen when you’re so drunk you can’t even hold your body upright and you’re vaguely attracted to the guy who creeps into the room where you’re fading in and out of consciousness. We didn’t talk about consent, let alone ongoing consent, enthusiastic consent. We didn’t talk about slvt-shaming, toxic masculinity, and misogyny in women, about the interconnectedness of all these things. We can’t identify what we don’t have the language for. And so I didn’t have words for what had happened to me. I knew that whatever it was, it felt wrong, but I wasn’t entirely aware of why I felt that way.

from Crying in the Bathroom, a 2022 memoir by Erika L. Sánchez

The refusal to acknowledge the word “cisgender” is very 1984. The concept of News Speak is to remove words so that the things they represent cease to exist. This is the same reasoning behind not providing SOGI education. If you don’t have words to describe yourself, you can’t be.

The moment I was taught what “transgender” means was the moment I finally knew how to describe what I had spent my life struggling with, and begin the journey to living an authentic life.

@NicESpurling 6:02 PM · Jun 18, 2021

HERMENEUTICS AND PHILOSOPHY

For that I refer you to the following post: 9 Facts About Hermeneutics from the Oxford University Press blog.

Header painting: Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), Mercury and Argus (c. 1659). For more paintings of Hermes in classic art, see this post.

WHILE WE’RE AT IT