Folklore refers to the traditional beliefs, customs, and stories of a community, passed through the generations by word of mouth. No one knows the origins of folklore.

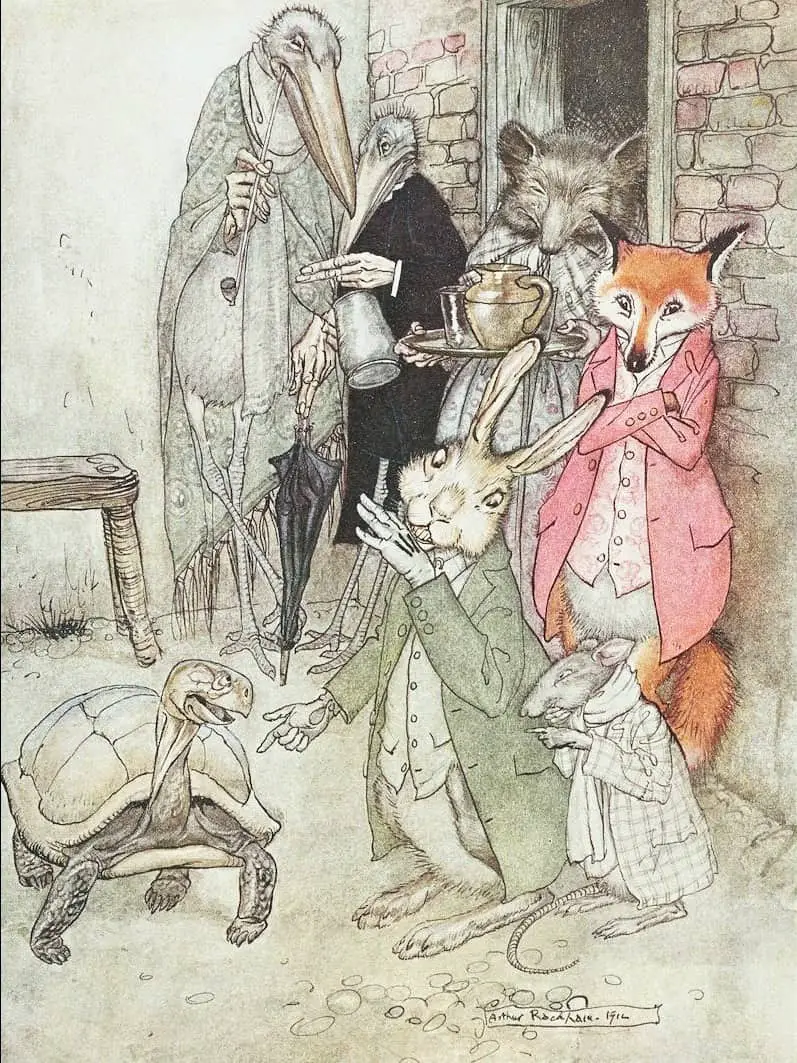

Fables are parables which star non-humans (animals). Contemporary speakers rarely make this distinction. Mostly nowadays ‘fable’ is sometimes used instead of ‘parable’.

Commentators know the lines have blurred and will now sometimes use the word apologue to describe a moral fable with animals as characters.

APOLOGUE

a moral fable, especially one with animals as characters.

(A parable is a succinct, didactic story, in prose or verse, which illustrates one or more instructive lessons or principles.)

In a fable, there is not necessarily any obvious moral but there is usually some kind of rough justice.

When it comes to the depiction of animals, and their closeness to humanity, folklore and fable are opposites.

Animals in Folklore

- talking animals

- clever animals who have an ambiguous or helpful role (the helper is one of Vladimir Propp’s seven character types)

- they may even have private lives and families based on the human model

- they may co-exist with human masters/owners/acquaintances

The Problem With Fables And Children

Fables, like fairy tales, came about before the concept of ‘child’ existed. In short, fables were not written for children. Here’s what we know about how children react to didactic stories:

Researchers from the University of Toronto read children, ages 3 to 7, three stories: George Washington and the Cherry Tree, Pinocchio or The Boy Who Cried Wolf. Only one of these stopped kids from telling a lie.

The story about George Washington telling the truth to his father about chopping down the tree, and the pride he felt that when his father praised his honesty, was the only effective story. Why did the researchers believe this worked? Because this story, unlike the others which feature high stakes and scary outcomes, featured positive consequences. In other words, instead of being scared, the kids focused on the lesson at hand. Learning not to lie.

And while the researchers didn’t point to realism, decades of research demonstrates that for young kids, realistic, relatable stories are more effective … So perhaps the fact that nearly any child can relate to wanting their father to be proud of them, rather than an obscure story about a wolf eating them, was a reason they actually got the point of the fable.

Scholars and Storytellers

Developmentally, children aren’t ready to understand and act on the morals of fables (or other kinds of stories) until they’re about nine years old.

For a related word, which may not immediately strike you as related to ‘fable’, see Fabulism In Children’s Literature.

The Folklore Authenticity Debate

The concept of authenticity is important to the study of folklore and folk narrative. Starting in the 1700s, people were searching for the genuine, the real, the unspoiled. This search had huge social, economic and political implications. The concept of ‘authenticity’ was generally associated with ‘traditional’ in the ‘tradition versus modernity’ binary view of the world. Old things are authentic; new things are fake. Once industrialisation happened mass production also happened. Mass produced goods weren’t valued as much as unique handmade objects. The handmade was considered more ‘real’.

The same thing happened with stories. Oral tales were considered authentic. Epic poems were considered especially authentic, especially by people (Romantic nationalists) wanting a narrative to replace the elitist language and culture of the monarchies.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, collections of folktales, as part of their marketing material, assured audiences that the tales had been recorded straight from the mouths of the common people and taken from unspoiled places.

In the 1960s, folklorists were arguing among themselves using the authentic/spurious binary, but this argument had long since been resolved. Folklorists now accept that folklore evolves with influence from pop culture (books, comics, film and so on).

OTHER RELATED WORDS

Under the broad term traditional literature are beast tales, cumulative tales, fables, fairy tales, folktales, fractured tales, Jataka tales, legends, myths, noodlehead tales, pourquoi tales, tall tales and trickster tales.

TRADITIONAL LITERATURE from A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and Using Picture Books by Denise I. Matulka

JATAKA TALES

Sometimes called birth stories, Jataka are accounts of the previous lives of the Buddha in various animal and human forms. They have been absorbed into the folklore of many countries. Jataka tales have many similarities to the Panchatantra and Aesop’s fables.

A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and Using Picture Books by Denise I. Matulka

Picture book examples

Buddha Stories (1997) illustrated by Demi

The Brave Little Parrot (1998) illustrated by Susan Gaber

Foolish Rabbit’s Big Mistake (1985) illustrated by Ed Young

FOLKLORE ARTIFACTS

Folktales, myths and legends are generally considered distinct types of narrative, or “folklore artifacts”. In 1965, a American folklorist, anthropologist, and museum director called William Bascom proposed a typology of prose narrative.

Bascom, W. (1965). The forms of folklore: Prose narratives. Journal of American Folklore, 78, 3-20.

According to Bascom’s typology, folktales are generally considered fiction by the teller and the audience. Folktales don’t have any historical origins. They often have a sense of timelessness about them.

In contrast, myths are considered historically factual and therefore sacred.

Legends are also considered factual. Legends can be either sacred or secular.

| FORM | BELIEF | TIME | PLACE | ATTITUDE | MAIN CHARACTERS |

| Myth | Factual | Antiquity | Different world | Sacred | Non-human |

| Legend | Factual | Recent Past | World of Today | Secular or Sacred | Human |

| Folktale | Fictional | Any Time | Any Place | Secular | Human or Non-human |

MYTHS

Myths are first and foremost about creation: why the earth/sea/day are as they are, who runs the world and how. Myths explain the otherwise inexplicable.

Every myth contains multiple timelines within itself: the time in which it is set, the time it is first told, and every retelling afterwards. Myths may be the home of the miraculous, but they are also mirrors of us. Which version of a story we choose to tell, which characters we place in the foreground, which ones we allow to fade into the shadows: these reflect both the teller and the reader, as much as they show the characters of the myth.

Pandora’s Jar, Women in the Greek Myths by Natalie Haynes

Myth In Western Children’s Literature

Myth as such is absent in the history of Western children’s literature. Unlike literature, myth is based on the belief of the myth bearers; when this belief disappears, the myth ceases to be a myth. Since children’s literature emerges long after Western civilization had lost its traditional mythical belief, this stage is not represented in children’s fiction.

Maria Nikolajeva, The Rhetoric of Character In Children’s Literature

Myths attempt to explain the beginning of the world, natural phenomena, the relationships between the gods and humans, and the origins of civilization. Myths, like legends, are stories told as though they were true. Myths are narrative projections of a culture’s origins, an attempt by a collective group to define its past and probe the deeper meaning of their existence. With complex symbolism, a myth is to a culture is what a dream is to an individual. Picture book examples are Atalanta’s Race: A Greek Myth (1995), illustrated by Alexander Koshkin; King Midas: The Golden Touch (2002), illustrated by Demi; Hercules (1999), illutrated by Raul Colon; and Cupid and Psyche (1996), illustrated by K.Y. Craft. Creation myths emerge from a culture’s desire to define creation and bring order to the universe. Picture book examples of creation myths include Moon Mother (1993), illustrated by Ed Young; The Star-Bearer: A Creation Myth From Ancient Egypt (2001), illustrated by Jude Daly; Adam and Eve and the Garden of Eden (2005), illustrated by Jane Ray; and The Woman Who Fell from the Sky (1993), illustrated by Robert Andrew Parker.

A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and Using Picture Books by Denise I. Matulka

The following mythologies are out of copyright and available at Project Gutenberg.

- The Iliad by Homer

- The Odyssey by Homer

- Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome by E. M. Berens

- Plays of Sophocles: Oedipus the King; Oedipus at Colonus; Antigone by Sophocles

- Myths of the Cherokee by James Mooney

- Myths and Legends of China by E. T. C. Werner

- 1000 Mythological Characters Briefly Described by Edward Sylvester Ellis

- Bulfinch’s Mythology by Thomas Bulfinch

- Myths of the Norsemen: From the Eddas and Sagas by H. A. Guerber

- A Book of Myths by Jean Lang

- Myths of Babylonia and Assyria by Donald A. Mackenzie

- The Children of Odin: The Book of Northern Myths by Padraic Colum

- Asgard Stories: Tales from Norse Mythology by Mabel H. Cummings and Mary H. Foster

- The Age of Fable by Thomas Bulfinch

- Myths & Legends of Japan by F. Hadland Davis

- The Golden Fleece and The Heroes Who Lived Before Achilles by Padraic Colum

- The Myths of the North American Indians by Lewis Spence

- Tales of Troy and Greece by Andrew Lang

- The Myths of Mexico & Peru by Lewis Spence

- Legends of Norseland by Mara L. Pratt-Chadwick and A. Chase

- In the Days of Giants: A Book of Norse Tales by Abbie Farwell Brown

- British Goblins: Welsh Folk-lore, Fairy Mythology, Legends and Traditions by Sikes

- American Hero-Myths: A Study in the Native Religions of the Western Continent

- Modern Mythology by Andrew Lang

- The Myth of Hiawatha, and Other Oral Legends, Mythologic and Allegoric, of the North American Indians

- Plant Lore, Legends, and Lyrics by Richard Folkard

- The Heroes; Or, Greek Fairy Tales for My Children by Charles Kingsley

- The Legends and Myths of Hawaii by David Kalakaua

- The Ancient Irish Epic Tale Táin Bó Cúalnge by Joseph Dunn

- Stories the Iroquois Tell Their Children by Mabel Powers

- The Babylonian Legends of the Creation by Sir E. A. Wallis Budge

- Myths and Legends of Ancient Egypt by Lewis Spence

- Myths and Legends of the Great Plains by Katharine Berry Judson

- Myths and Legends of Our Own Land — Complete by Charles M. Skinner

- The Book of Nature Myths by Florence Holbrook

- The Fairy Mythology by Thomas Keightley

- Stories of Old Greece and Rome by Emilie K. Baker

- Myths and Legends of All Nations by Logan Marshall

- Mythical Monsters by Charles Gould

- Indian Myth and Legend by Donald A. Mackenzie

- Myths and Legends of the Sioux by Marie L. McLaughlin

- The Heroes of Asgard: Tales from Scandinavian Mythology by Keary and Keary

- The Unwritten Literature of the Hopi by Hattie Greene Lockett

- The High Deeds of Finn and other Bardic Romances of Ancient Ireland by Rolleston

- Curious Myths of the Middle Ages by S. Baring-Gould

- Myths and Folk-tales of the Russians, Western Slavs, and Magyars by Jeremiah Curtin

- Legends of Gods and Ghosts (Hawaiian Mythology) by W. D. Westervelt

- A Book of Giants: Tales of Very Tall Men of Myth, Legend, History, and Science

- Tales of the Enchanted Islands of the Atlantic by Thomas Wentworth Higginson

- Children of the Dawn : Old Tales of Greece by E. F. Buckley

- Stories from Northern Myths by Emilie K. Baker

- The Mythology of the British Islands by Charles Squire

- Myths and Legends of California and the Old Southwest by Katharine Berry Judson

- The Arabian Nights Entertainments by Andrew Lang

- East of the Sun and West of the Moon Old Tales from the North by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen & Jørgen Engebretsen Moe

- Hero-Myths & Legends of the British Race by M. I. Ebbutt

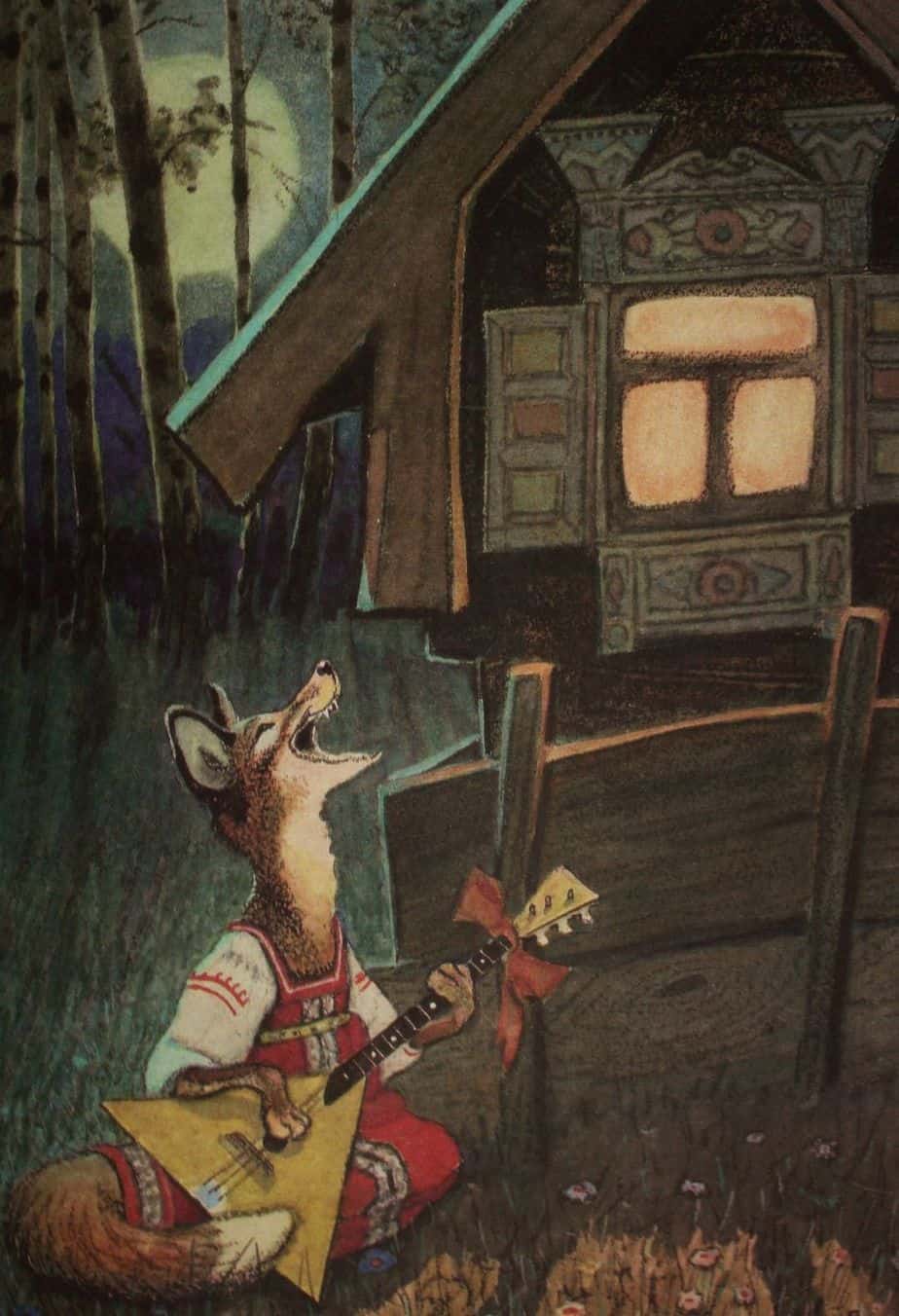

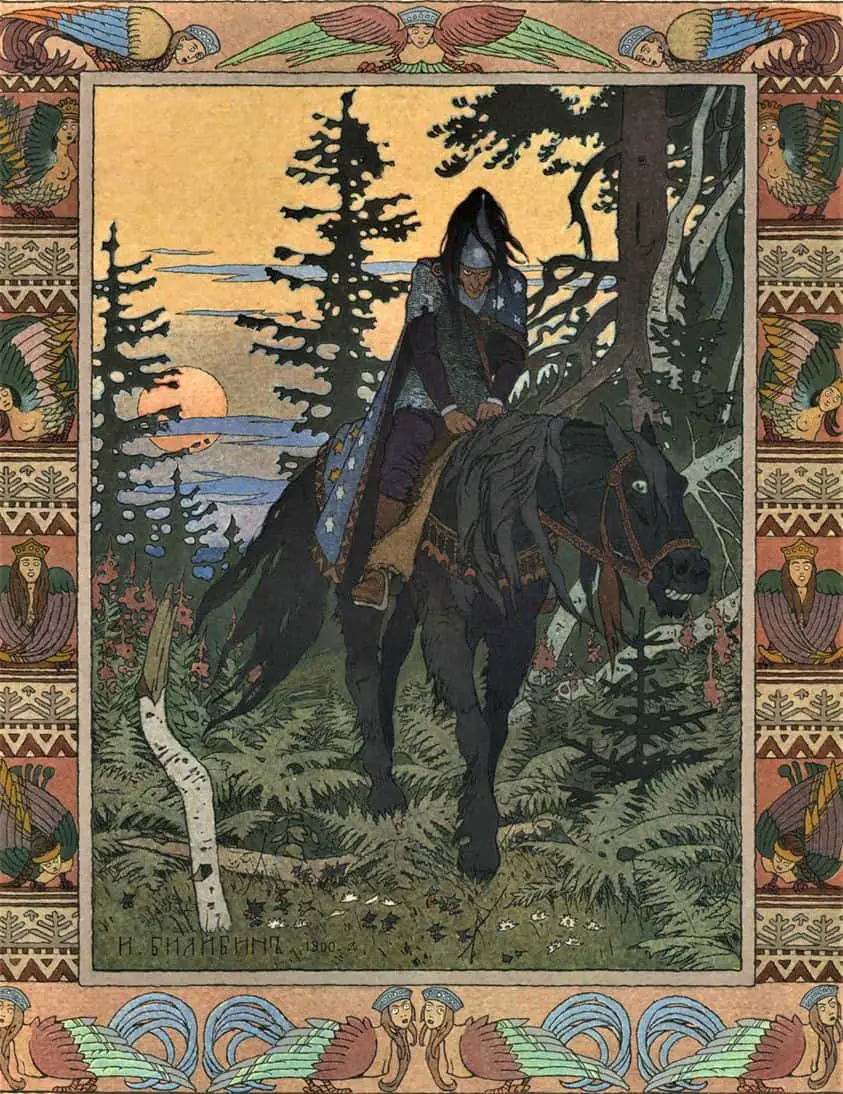

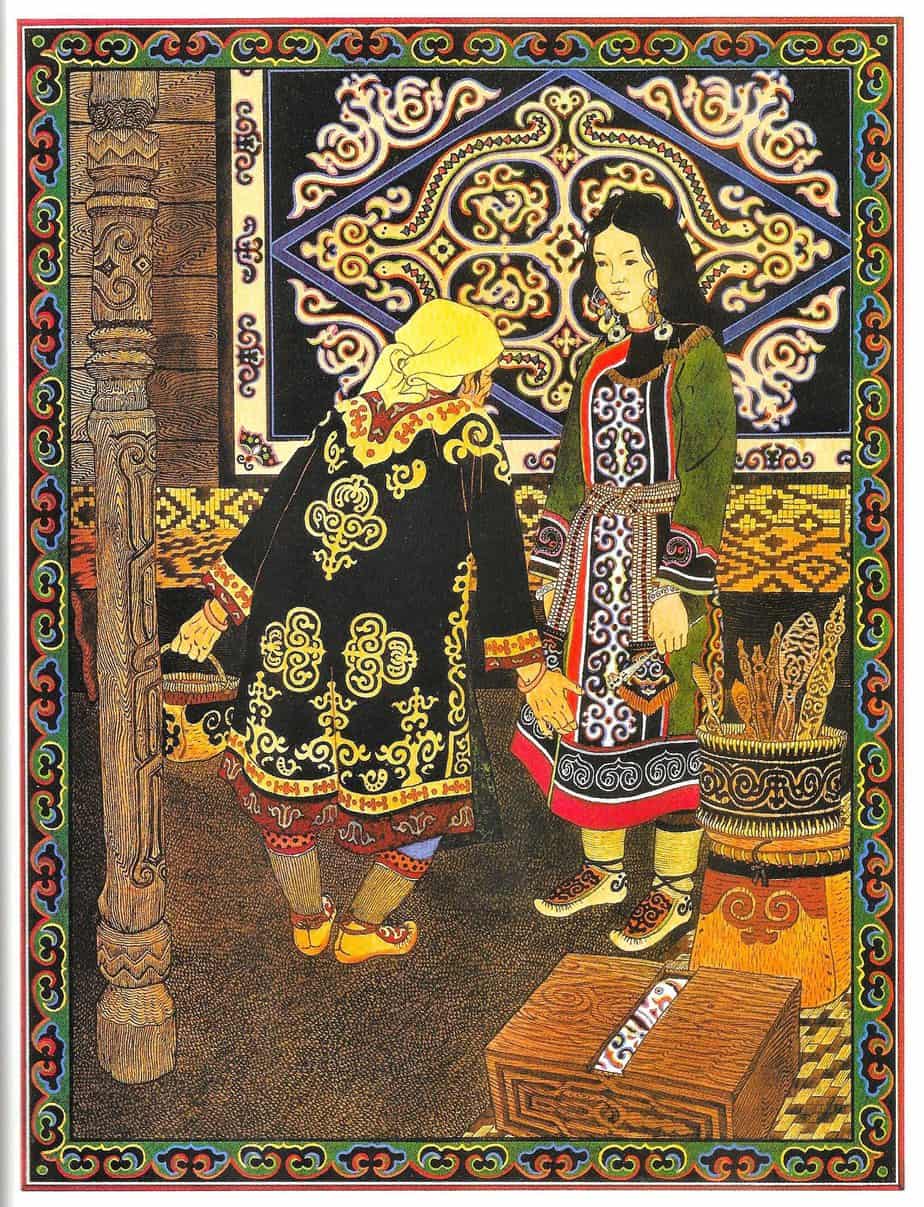

FOLK TALES

Are the traditional tales of the people. Folktales are often fairy tales, but not always. Folk indicates the origin of the story, while fairy indicates its nature.

Folktales feature common people, such as peasants and farmers, and commonplace events. Characters are usually flat, representing an everyman or everywoman. Folktales have tight plot structures, filled with conflict. Cycles of three often appear in folktales. Elements of magic or magical characters may be incorporated, but logic rules, so the supernatural must be plausible and within context. Picture book examples of folktales include The Little, Little House (2005), illustrated by Jessica Souhami; Hansel and Gretel (1984), illustrated by Paul O. Zelinsky; Koi and the Kola Nuts: A Tale from Liberia (1999), illustrated by Joe Cepeda; and Rhinos for Lunch and Elephants for Supper! (1992), illustrated by Barbara Spurll.

A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and Using Picture Books By Denise I. Matulka

Beauty and the Beast is understood as a literary fairy tale, written down by a specific individual. But like many modern(-ish) stories, Beauty and the Beast has its origin in folktale. Folklorists devised a way of categorising folk tales. It’s called the Aarne-Thompson-Uther index of international folktales. Beauty and the Beast is of tale type 425C, a variation on the tale-type known as The Search For The Lost Husband. Cupid and Psyche likewise fits into this category.

Both tales include:

- a meeting between a beautiful girl and a supernatural or enchanted groom

- their separation as a result of the beautiful girl’s transgression

- reunion at the end

The stories make use of different characters, symbolic objects and motifs, but the basic plot is the same. This is representative of how folktales evolve and interconnect.

When illustrated, folk tales tend to incorporate folk art techniques. Ivan Billibin and Viktor Vasnetsov are big names in Russian folktale illustration.

Russian folklorists have their own approach to the study and classification of folktales. Afanas’ev and Fyodor Buslaev are big names in this area of study. During the 19th and early 20th century, these guys interpreted folktales as remnants of ancient myths.

Dmitry Zelenin, Nikolai Onchukov and others took a different route again. They collected Russian folk tales to highlight the abject poverty of the citizens who told them.

Iu. M and B.M. Sokolov published a two-volume collection of folktales from the White Lake area. Alongside the collections of Afanas’ev and Onchukov, this is considered a great achievement in folklore.

More recently, you may have heard of Vladamir Propp. His book Historical Roots of the Wondertale (1946) has been influential. Propp has influenced Elena Novik, Irina Razumova and Elena Shastina.

Musical composers such as Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Pyotr Il’ich Tchaikovsky have been influenced by Russian folklore and fairytale.

This also applies to filmmakers such as Aleksandr Rou.

- Demonology and Devil-lore by Moncure Daniel Conway

- Hawaiian Folk Tales by Thomas G. Thrum

- Welsh Folk-Lore by Elias Owen

- The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries by W. Y. Evans-Wentz

- Folk Tales Every Child Should Know by Hamilton Wright Mabie

- Guernsey Folk Lore by Sir Edgar MacCulloch

- Folk-Lore and Legends: English by Charles John Tibbitts

- Philippine Folk Tales by Mabel Cook Cole

- Folk Tales from the Russian by Kalamatiano De Blumenthal and Verra Xenophontovna

- The Folk-Tales of the Magyars by Erdélyi, Kriza, Pap, Jones, and Kropf

FABLES

Fables are short prose pieces or verse with a moral ending. The characters are animals and other inanimate objects that take on human characteristics, such as talking and expressing emotions. The form is generally ascribed to Aesop, who developed it in the sixth century BC. Aesop’s fables are very well known in the West. Other famous fables include the Panchatantra, a collection of fables written in Sanskrit. Picture book examples are Fables (1980), illustrated by Arnold Lobel; Doctor Coyote: A Native American Aesop’s Fable (1987), illustrated by Wendy Watson; The Lion and the Mouse (2000), illustrated by Bert Kitchen; and The Ant and the Grasshopper (2000), by Amy Lowry Poole.

A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and Using Picture Books by Denise I. Matulka

See also: The Difference Between Folklore and Fables

FAIRY TALES

Are stories of magic, set in the indefinite past, incorporating traditional themes and materials. Often about giants, dwarfs, witches, talking animals, a variety of other creatures — good and bad fairies, princes, poor widows etc. In fact, there is a standard cast of characters who appear in fairy tales.

Some fairy tales are ancient; others are modern. The tradition of the modern fairy tale began with Uncle David’s Nonsensical Story in Catherine Sinclair’s Holiday House.

- Japanese Fairy Tales by Yei Theodora Ozaki

- Irish Fairy Tales by James Stephens

- Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry by W. B. Yeats

- Russian Fairy Tales: A Choice Collection of Muscovite Folk-lore by Ralston

- American Fairy Tales by L. Frank Baum

- The Norwegian Fairy Book by Klara Stroebe

- Japanese Fairy Tales by Grace James

- American Indian Fairy Tales by W. T. Larned

- The Indian Fairy Book by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft

- Celtic Folk and Fairy Tales by Joseph Jacobs and John Dickson Batten

- Grimms’ Fairy Tales by Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm

- The Cat and the Mouse: A Book of Persian Fairy Tales by James and Neill

- Dutch Fairy Tales for Young Folks by William Elliot Griffis

- Andersen’s Fairy Tales by H. C. Andersen

- My Book of Favourite Fairy Tales by Edric Vredenburg

- Jewish Fairy Tales and Legends by Gertrude Landa

- Welsh Fairy Tales by William Elliot Griffis

- Cinderella in the South: Twenty-Five South African Tales by Arthur Shearly Cripps

- Fairy Tales of the Slav Peasants and Herdsmen by Alexander Chodzko

- Welsh Fairy-Tales and Other Stories by P. H. Emerson

- English Fairy Tales by Joseph Jacob

- The Swedish Fairy Book by Stroebe, Hood, and Martens

LEGENDS

Legends are about the achievements of real or imaginary heroes — battles from long ago. The term originally referred to the biography of a saint. There’s a German language cognate ‘legende’ which refers to that narrower use of the term, but in English, folklorists now use ‘saint’s legend’ if they mean specifically the life and times of a (Christian) saint. The word for a saint’s biography is ‘hagiography’. This genre emerged in the fifth century, and stories were designed to provide a direct link between God and the common people, with the heroism of saints as models for how to live a good life. If you lived through the middle ages and Renaissance, you would’ve been subjected to a lot of stories about saints. The most famous of those was The Golden Legend (Legenda aurea), put together by Jacobus de Voraigne c 1260.

Today, a legend doesn’t have the religious connotations.

- The Legends of King Arthur and His Knights by Knowles and Malory

- Studies on the Legend of the Holy Grail by Alfred Trübner Nutt

- Legendary Heroes of Ireland by Harold F. Hughes

- Myths & Legends of the Celtic Race by T. W. Rolleston

- The Topaz Story Book Stories and Legends of Autumn, Hallowe’en, and Thanksgiving

- Gods and Fighting Men by Lady Gregory

- Legends That Every Child Should Know

- The Indian Fairy Book: From the Original Legends by Cornelius Mathews

- Old-World Japan: Legends of the Land of the Gods by Frank Rinder

- Basque Legends; With an Essay on the Basque Language by Wentworth Webster

FANTASY

Is a modern form, belonging to the age of the novel. There are many different subcategories of fantasy. Fantasy overlaps with fairytales, though fantasy tends to be long while fairy tales are brief. Fantasy has tended to be a British speciality, at least in the 19th Century. Fantasy from newer countries has gone more for stories about contemporary life, though globalisation means any regional distinction is now less marked.

Fantasy took off in the decade of Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland and The Water Babies. (1865 and 1871.)

for more see John Rowe Townsend, Written For Children

See also: Evaluating Fantasy in Children’s Literature

BEAST TALES

Beast tales feature animals that behave like humans. This type of folktale can be either serious or funny. Unlike fables, there is no explicit moral to the story in a beast tale. Examples of beast tales are “The Three Bears“, “Henny Penny,” and “The Three Little Pigs“. The animals embody various human traits; this feature is also known as anthropomorphism. In a beast tale the animals interact with humans, but the humans are secondary characters. Picture book examples are The Three Little Pigs: An Old Story (1988), illustrated by Margot Zemach; The Bremen Town Musicians (2007), illustrated by Lizbeth Zwerger; and Henny Penny (1979), illustrated by Paul Galdone.

A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and Using Picture Books by Denise I. Matulka

URBAN LEGENDS

Like folktales, urban legends are mostly transmitted. But the term is a little hard to pin down. Here are the difficulties around easy explanation:

- Despite being called ‘urban’, these stories rarely happen in an urban storyworld. In case you’re thinking ‘They must be told by people living in urban spaces, then’, that’s not true, either. Urban legends can take place in any fictional setting and are recounted by anyone anywhere, also. Instead, it seems ‘urban’ simply means ‘Western modernity’.

- Despite being called ‘legend’, and despite ‘legends’ being understood as somewhat grounded in truth, tellers and listeners of urban legends don’t tend to think that urban legends are really true. Instead, urban legends are about what could be true. It would be more accurate, then, to call these stories ‘modern folklore’.

Urban legends often utilise macabre and gruesome motifs from the horror genre. They are also very much connected to local pop culture.

They’re not just about entertainment. They function as cautionary. They also provide explanations for random events.

WONDER TALES

Wonder tale is another word for fairytale. Thomson of Aarne-Thomson defined a wonder tale as: “A tale of some length involving a succession of motifs or episodes. It moves in an unreal world without definite locality or definite creatures and is filled with the marvelous.”

- Wonder Stories: The Best Myths for Boys and Girls by Carolyn Sherwin Bailey

- Wonder Tales from Many Lands by Katharine Pyle

Fables have been parodied for a long time. The header illustration is from Fables for the Frivolous (1899) by Guy Wetmore Carryl, illustrated by Peter Newell