There is a spectrum of how real-world a story feels. Realism is a widely misunderstood term even within literary studies today. The terms are used differently depending on location. They’re also heavily classed and slightly gendered to boot. Humanities scholars spend a lot of time arguing about the meaning of realism.

But let’s at least try. I offer a classification via continuum, with fully realistic at one end and more fantastical at the other.

At the ‘realistic’ end we start with naturalism. At the other is ‘speculative realism’. After that we’re firmly in speculative fiction realm.

Some commentators link Realism to the Gothic in the history which gets us to the Modern Novel. Some see the Gothic novel in England and the United States of America as anticipating the Modern Novel. The Realist novel in this scenario is an ‘interlude’.

NATURALISM

This term is often used interchangeably with realism. But if you want to talk about realism as a group of terms, naturalism is at the MOST realistic of these different types of realisms. Basically, any hint of romanticism is completely stripped away. The subject is neither idealised nor flattered. Writers also keep God right out of the picture. The tone is generally pessimistic.

Realism/naturalism emerged in the 1800s. Sometimes the difference between naturalism and realism depends on the subject matter, or rather, the perceived class of the person who wrote it.

In works labelled ‘realism’, the main focus is on the middle class and its problems. Naturalism often focuses on less educated or lower-class characters. This word is also often used to describe work involving violence and the taboo. So, things which middle class reviewers and commentators find uncomfortable, alien and other.

SOCIAL REALISM AND KITCHEN SINK DRAMA

For much of the twentieth century, one of the most salient features of

literary production and reception was the cultural, institutional, and critical division of fiction into the two admittedly broad, but nonetheless clearly distinguishable, categories of genre and literary fiction. Margaret Atwood, whose own work has for many years crossed and re-crossed genre boundaries, has recently argued that from the mid-twentieth century the socially realistic novel has been seen as a critical standard. As a result, ‘anything that doesn’t fit this mode has been shoved into an area of lesser solemnity’, a literary ghetto inhabited by the thrillers, fantasy novels, and other sub-literary works condemned for ‘the misdemeanour of being enjoyable in what is considered a meretricious way’.Michael Chabon has similarly argued that around 1950 a ‘fateful and perverse decision’ was made to separate from and elevate above all other types of fiction ‘the rules, conventions, and formulas’ of the genre known as literary fiction. This fracture meant that all other types of fiction were considered to be de facto ‘fundamentally, perhaps inherently, debased, infantile, commercialized, unworthy of a serious person’s attention’. Edmund Wilson’s 1945 dismissal of detective stories as a vice, ranking ‘for silliness and minor harmfulness … somewhere between crossword puzzles and smoking’ is a typical example of

the sort of attitude Atwood and Chabon describe, and this fundamental

division of all works of fiction, long and short, serious and frivolous, well-wrought or mis-thrown, into two reified categories is arguably the primary fact of twentieth century literary history.In the twenty-first century, the separation between literary and genre fiction appears to be increasingly untenable as the seemingly insuperable obstacles between them erode. As Atwood notes, the intensity with which the borders between genres are policed is decreasing and, as a result, ‘things skip back and forth across them with insouciance’. Many literary writers have begun to adopt elements of genre fiction into their own work, or indeed to produce outright pieces of what would traditionally be classed as genre fiction. Atwood herself has written a number of Science Fiction novels, including The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) and the recently concluded MaddAddam trilogy; Chabon’s Gentlemen of

the Road (2007) is a novella of swashbuckling adventure; Cormac McCarthy won the Pulitzer prize for his post-apocalyptic The Road (2006); Thomas Pynchon’s latest novels Inherent Vice (2009) and Bleeding Edge (2013) fall within the traditions of the detective novel; and Colson Whitehead’s Zone One (2011) is, almost unbelievably, for even in times of radical change some limits seem insurmountable, a literary zombie novel. Examples could of course be multiplied, but clearly the strict differentiation between literary and genre fiction is, in practice, weakening.This hierarchical division is also under increasing theoretical pressure, as critics and scholars have for a number of years been turning their attention to the world of genre fiction. Part of this stems from a recognition that the novel as a literary form – a genre, in fact – relies on an unceasing oscillation between ‘High and Low forms’ for its existence.

The Interstitial City and China Mieville’s Equivocal Hybridity by Eric Sandberg, University of Oulu, Finland, C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Writings, Vol. 3, No. 1 (2014)

You’ll also hear the term ‘Kitchen sink realism’. This sometimes describes work which draws attention to the middle class and its problems. ‘Kitchen sink realism’ or ‘Kitchen sink drama’ were terms coined to describe a British cultural movement which developed in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The United Kingdom experienced massive cultural change in this era. The Conservative Party won the 1951 election with their slogan “Set the People Free”. The British public felt more free, more affluent and eager to shuck off the rigidity of the past. People were questioning and ridiculing the cultural conventions which came before.

John Bratby was a painter who lived 1928–1992. His paintings are a standout example of Kitchen Sink art. See, for instance “The Toilet“, a 1955 painting of an actual toilet. Bratby was also a writer. The ‘Kitchen Sink art‘ tag at the Tate Modern includes Edward Middleditch and Peter Coker in its results. Paintings sport titles such as “Mother, Child and Bedsprings” and “Still Life With Chip Fryer”.

The main characters of so-called kitchen sink dramas were frequently angry young men. Kitchen sink dramas utilised social realism which, to British art looks like:

- Britons living in cramped rented accommodation

- Evenings spent drinking in dank local pubs

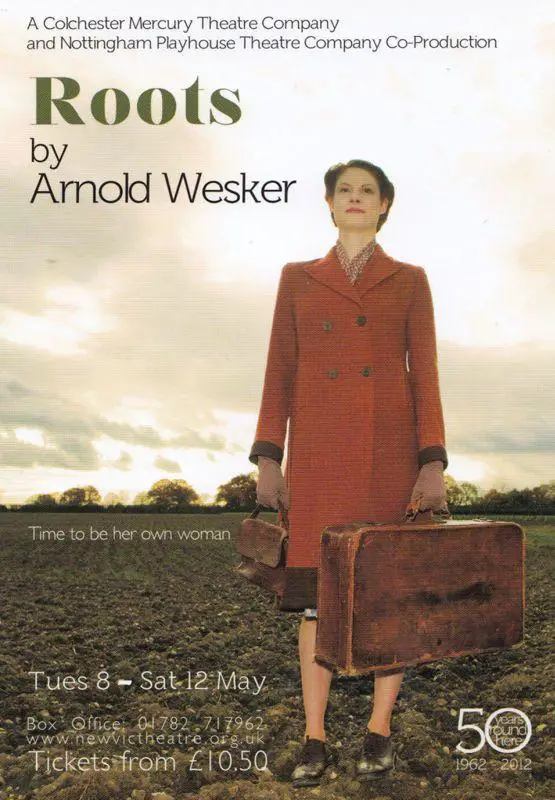

Kitchen sink drama started as a condescending term but these days people might try to use it without ascribing morality. Early storytellers who departed from writing upper-class stories set in drawing rooms included Arnold Wesker and Alun Owen.

Arnold Wesker’s play Roots (1959) literally opens with a character washing dishes at a kitchen sink.

Roots focuses on Beatie Bryant as she makes the transition from being an uneducated working-class woman obsessed with Ronnie, her unseen liberal boyfriend, to a woman who can express herself and the struggles of her time. It is written in the Norfolk dialect of the people on which it focuses, and is considered to be one of Wesker’s kitchen sink dramas. Roots was first presented at the Belgrade Theatre, Coventry in May 1959 with Joan Plowright in the lead before transferring to the Royal Court Theatre, London.

Wikipedia

(Gene Wilder, who older readers may know as Willy Wonka from the first movie adaptation of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory got his start in an American production of Roots.)

Look Back In Anger, a 1956 play by English playwright John Osborne, is another early standout example of Kitchen Sink Realism. Typically for the category, the main character is a working class angry young man by the name of Jimmy Porter. This character captured the angry and rebellious spirit of the post war generation.

There are a handful of films, all produced between 1959 and 1963 considered part of the New Wave Kitchen Sink canon. Aside from Look Back In Anger, those films include:

- Room At The Top (1959): In late 1940s West Riding of Yorkshire, England, Joseph (Joe) Lampton, an ambitious man who has just moved from the dreary factory town of Dufton, arrives in Warnley to assume a secure, poorly paid post in the Borough Treasurer’s Department.

- Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960): A young machinist, Arthur, spends his weekends drinking and partying, all the while having an affair with a married woman.

- A Taste of Honey (1961): Set in Salford in North West England in the 1950s, this film tells the story of Jo, a seventeen-year-old working class girl, and her mother, Helen, who is presented as crude and sexually indiscriminate.

- A Kind of Loving (1962): Vic Brown, a young working class man from Yorkshire, England, is slowly inching his way up from his working-class roots through a white-collar job. Vic finds himself trapped by the frightening reality of his girlfriend Ingrid’s pregnancy and is forced into marrying her and moving in with his mother-in-law due to a housing shortage in their Northern England town.

- L-Shaped Room (1962): from the 1960 novel by Lynne Reid Banks, who you may recognise for her children’s books. A 27-year-old French woman, Jane Fosset (Caron), arrives alone at a run down boarding house in Notting Hill, London, moving into an L-shaped room. Beautiful but withdrawn, she encounters the residents of her house, each a social outsider in his or her own way, including a gay black horn player. She is pregnant and does not want to marry the baby’s father.

- Billy Liar (1963): William Fisher, a working-class 19-year-old, lives with his parents in the fictional town of Stradhoughton in Yorkshire. Bored by his job as a lowly clerk for an undertaker, Billy spends his time indulging in fantasies and dreams of life in the big city as a comedy writer.

- This Sporting Life (1963): A rugby league footballer, Frank Machin, lives in Wakefield, a mining city in Yorkshire. His romantic life is not as successful as his sporting life.

However, there were a number of very good ‘B-side’ (low-budget) Kitchen Sink dramas which, purely for economic reasons (not artistic ones) are not considered Kitchen Sink canon.

- The Leather Boys (1963, 1964): Dot and Reg are a young Cockney couple who get married then start to fall out of love. Reggie grows closer to his friend Pete. At the end of the film, Reggie is revealed to be gay. The film is based on a 1961 book by Mary Ann Evans (published under the pseudonym Eliot George). The novel makes much more of the gay storyline.

- That Kind of Girl (1963): This is a sexploitation film, but also happens to be the first British film to deal with the issue of STIs (or VDs as they were called back then).

- This Is My Street (1964): Set in Battersea, Margery Graham is a working class housewife who feels stifled by her circumstances. So she has an affair with her mother’s lodger. She attempts suicide after he fails to return her affections. The setting is a South-West London in the throes of post-war reconstruction.

- The Little Ones (1964): Two boys, Jackie and Ted, decide to run away from home together. Ted comes from a one-room East End flat and his mother is physically abusive. Jackie’s mother is a sex worker who doesn’t care much for her own offspring (a la Fish Tank, a contemporary example of domestic realism). Jackie’s absent father is from Jamaica, so the boys plan to make their way there.

- The Family Way (1966): Just a few years later, this film sits right on the border between Kitchen Sink drama and what came next — the Swinging Sixties (which didn’t happen until the late 1960s). This border has been called ‘The Mid-decade Divide’, but was written five years before release. In the story, a young woman called Jenny is newly married to a young man called Arthur. They’re unable to have sex and are under heavy pressure to do so by their family and social network. Arthur is roundly humiliated.

In 1966 the BBC commissioned Ken Loach to adapt the Jeremy Sandford play Cathy Come Home. This is the story of a young working-class couple called Cathy and Reg Ward. They start their married life full of hope but then Reg loses his job. They have to move into council housing. They have three kids and then they are evicted. They move into a caravan. The caravan burns down and the couple split up. The story only gets worse from there, but this film proved really popular across Britain. Cathy Come Home was one of the few stories to highlight the British housing crisis of the late 1960s. (Ken Loach then went on to have a full and successful career making feature-length films.)

This film did much for the status of documentary.

Social realist films often make use of the hand-held camera for added verisimilitude.

Note that ‘social realism’ frequently describes Australian, New Zealand and British working-class fiction but not North American fiction. Notice, too, the classism. When writers from the middle and upper socio-economic classes write about their own lives and childhoods reviewers frequently describe them as ‘beautiful’ writers. With working class authors and subject matter, those same reviewers use the descriptor ‘realist’.

SURREALISM

Describes the ‘super real’. See this post for more.

MAGICAL REALISM AND FABULISM

Lately there is a movement among Latinx people from South America to keep the term magical realism specifically for South American writers using magical realism to write stories about the South American experience of colonisation.

The argument is that another word exists which we can use for everything else — fabulism.

While I have some sympathy for this view, literary gurus point out that magical realism did not begin in South America, and there are many reasons for making use of magical realism in storytelling.

I don’t know. I’d be happy to call it fabulism myself, if people knew I meant the same thing as ‘magical realism’, only not from South America.

Fabulism is especially popular in literary middle grade fiction, and I’ve noticed literary agents and editors are constantly on the hunt for it, and keep complaining that true examples of magical realism rarely cross their desk.

Here is a list of fabulist children’s books.

‘DIRTY’ REALISM AND KMART REALISM

This is a concept coined by the Granta Magazine guy. He is actually an American who moved to England. So the term is used in England, whereas Americans might call the same thing ‘minimalism’.

Dirty realism describes a specifically North American way of writing. The author focuses on the seedier, mundane, nasty bits of everyday life.

Many of these writers are white men: Richard Ford, Cormac McCarthy, Raymond Carver. But there are also some women. Take Carson McCullers, Annie Proulx.

When you find dirty realism in a short story, it’s often called Kmart Realism.

METAPHYSICAL REALISM

There is a reality independent of humans’ conscious perceptions of it. The world is as it is and what humans think of it is irrelevant. If this describes your worldview, here’s your metaphysical realist card.

SPECULATIVE REALISM

Okay, so are we still talking about realism now? This is a term suggested by a guy called Ramón Saldívar (an American professor and author) to describe work which is a hybrid between speculative genres and any of the different levels of realism.

In children’s literature, the book American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang is a contender for speculative realism. American Born Chinese is an experiment in discussing minority racial identity through metaphor made possible through genre blending. The experiment leaves us ultimately with a parallel between a monkey god from folklore and a young adult American-born-Chinese in a realistic context. For more on that, see here.

ANTI-REALISM

Michael Dummett coined this term in the 1970s.

Realism assumes there’s objectivity in the world. Is there an atmosphere around Earth? Yes. How characters feel about that isn’t really relevant.

Anti-realism deals in subjectivity. Are there ghosts in your house? Well, if you think you see ghosts, there might as well be, because you’re terrified all the same.

The Turn of the Screw by Henry James (1898) is an example of anti-realism. In that story, James was shifting away from his usual psychological realism and inching closer to Modernism. He made use of many features of the so-called feminine gothic form.

FURTHER READING

Donald Maass talks about the Three Modes of Story Imagination, which reads a little like a ‘personality test for writers’. (I’m sure it’s a spectrum — everything is.) Writers fall into the following main categories:

- Seeing the story as if a life plays out like a movie

- Imagining the most resonant scenes

- Crafting beautiful language and building a story around that

Which of those feels like a fit for you? Each of these ways of imagining story has its advantages and pitfalls. Regarding number two, Maass has this to say:

When writers think, “I need to show that…” or “Readers need to see…” they are building the body of their manuscripts toward, or sometimes away from, the big turnings that are the true reasons for a story to be written in the first place. The advantage of this way of imagining story is that it puts emphasis on what is dramatic. The disadvantage is that such manuscripts can wander, trying always to hammer significance into intervening action in which it doesn’t exist.

Donald Maass, Writer Unboxed

Bringing that back to realism, some ways of imagining lead writers naturally towards too much realism and not enough interestingness.

REALISM IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

Bear in mind, children’s literature is a recent form of literature and emerged with the establishment of realism.

Many of the notes below are from Professor David Beagley, La Trobe University, Genres In Children’s Literature: Lecture 13: “Realism In Fiction For Children”.

REALISM FOR MIDDLE GRADE READERS

Set reading for this lecture: Bridge To Terabithia and The Naming of Tishkin Silk

My Girl (the film) is an interesting work to contrast with Bridge To Terabithia because the plot is similar. Both feature a girl and boy the same age across stories. The difference is, My Girl is aimed at an adult audience.

Helicopter Man is another example of realism, aimed at upper primary school rather than high school aged reader.

Pete’s dad is being pursued by a secret organisation. Both their lives are in danger and when the helicopters hover nearby they must hide. Pete knows he leads an unusual life, but he’s never dared ask questions before. Now he needs some answers. His dad’s behaviour is starting to confuse him. But when Pete starts to piece the scraps of information together, what will he discover? Who, exactly, are they running from? And why is his father really behaving so strangely?

Throughout the 20th century, British children’s literature is thought to have produced better and more lasting classic fantasy series than North America, which has leaned towards realism for longer.

Right around middle school, the fun books suddenly disappeared. Dreary realism replaced fantasy.Read Hatchet. Read Shiloh. Read Sounder. Read The House of Dies Drear. Read about kids in the Great Depression, whose dogs always die. Read about the gruesome fact of slavery. Read about Anne Frank in the attic. Today, class, we’ll be reading a graphic novel! […] it’s called Maus. No wonder I kept my nose buried deep in Dragonlance novels and The Collected Calvin & Hobbes. Eventually I accepted that the mark of serious, grown-up books was joy turning into woe. Merry old Gatsby is really a huge fraud who bites it in a swimming pool and no one cares but his neighbour. The end. Jake Barnes is living it up in Paris with Brett Ashley, but he got injured in the war and they can’t have sex, so… the end. The older I got the more books seemed to skip the joy part altogether—they just went from woe to more woe. The Joads are starving in the Great Depression so they head West but find that everyone else is starving too and then somebody dies in the back of a truck… the end. Frank and April Wheeler are hopeful suburbanites who dream of moving to Paris but then she gets pregnant and dies trying to give herself an abortion. The end!

Why Children’s Books Matter

There is a certain kind of magic about realism in middle grade books, which is not magical at all, and not magical realism, either, but magic.

I think there’s a kind of kid for whom an adventure based in realism — even if it’s stretched almost to the breaking point of plausibility — is so much more satisfying than pure fantasy. Because I knew for sure that I was never going to end up communing with a gang of bugs inside the pit of a ginormous peach — and I loved that book, I did. I loved the Narnia books, too, and the Wrinkle in Time series. But I had a special fondness for stories that could actually happen. Which explains, I think, something about the plot of One Mixed-Up Night. It is certainly unlikely that two kids would spend the night alone in a massive Swedish furniture store. But it is not impossible. And I had spent enough time listening to my son Ben and his best friend Ava leafing through the IKEA catalogue to know that having the run of the place was high on their list of fantasies. Were they ever going to spend a semester at Hogwarts? Of course not. But IKEA! That was an actual place where we actually went. What if they ditched their parents? What if that stylish and birch-patterned world became their oyster? I mean, it wasn’t likely to happen. But it could…

Catherine Newman

HIGH SCHOOL READERS

Realism tends to be aimed at the high school reader. It began in earnest with J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher In The Rye (1951). Be wary of conflating ‘social realism’ with ‘universal realism’:

In a 2009 BBC article, it’s mentioned that The Catcher in the Rye is unique in “the way in which a young affluent white male has come to stand for a universal experience of adolescence.” I don’t think it’s unique – I think it’s what society has forced the “universal experience” to be. Opinions and experiences of minorities are attributed to being that of the minority group. What if Holden was a girl? At least part of her angst would be attributed to some sort of weak womanly temperament, or her period. What if Holden was poor? Would he have even been able to get the money to go back to New York? What if Holden was a POC? Had a disability? Was gay?

No, he couldn’t be anything but a white, middle class, teenage boy, because he would’ve had more issues to deal with along with phony people.

Starchy Thoughts

This tentpole novel has been followed by work from authors such as:

- S.E. Hinton

- Robert Lipsyte

- Paul Zindel

- Richard Peck. Peck sometimes writes realism, sometimes historical realism (e.g. The River Between Us), sometimes realism with a humorous, exaggerated touch (e.g. A Long Way From Chicago), sometimes he writes fantasy (e.g. his mouse stories).

- Norma Klein lived from 1938 to 1989 and wrote about ‘the things real kids cared about’.

- M.E. Kerr couldn’t find an agent for her realistic stories so became her own agent. She ended up with a lifetime award for her contributions to children’s literature. She wrote under a variety of different pen names.

- Norma Fox Mazer and Harry Mazer. Norma lived between 1931-2009. The husband/wife couple had four children and were teacher/writers. Although they both wrote the same sort of thing, they didn’t work together. Each has their own books. Harry was born in 1925 and died recently, in 2016.

- Robert Cormier. The Chocolate War initiated a new level of excellence in young adult literature but also unleashed a storm of controversy. (Cormier didn’t intend a YA audience, actually. He wrote it for a general audience and it was marketed as YA.) Gatekeepers felt the subject matter was too dark. Cormier followed up with I Am The Cheese and After The First Death, in the same vain, ignoring the naysayers. He continued to get darker over the 26 years of his writing career. He definitely influenced other authors, who started to do the same.

If you notice more realism coming out of America, that’s because realism in children’s literature is largely American, whereas a lot of the most beloved fantasy comes out of Britain.

Australia has its own examples of realism in children’s literature. Australian literature for adults tends to be described as ‘gritty realism’. Take Helen Garner for instance, or the work of Christos Tsiolkas, who sometimes writes about young adulthood. The TV adaptation of Barracuda has a distinctly YA feel about it — more so than the novel upon which it is based.

The Valley Between by Colin Thiel is about the author’s own life, growing up in the Barossa Valley.

For more examples of realistic books themselves, search for Books in the category ‘Real Life’ e.g. at the Reading Matters website.

ACADEMIC READING ON REALISM IN CHILDREN’S BOOKS

Only Connect. Sheila Egoff died in 2005 but was an enthusiast for the proper intellectual consideration of children’s literature. Being Canadian, she had a huge impact in Canada. (A Canadian literature prize has been named after her.)

John Foster, Ern Finnest, Maureen Nimon: Australian Children’s Literature, an Exploration Of Genre and Theme, 1995 looks at family stories and the ‘problem’ novel.

Perry Nodelman’s book The Hidden Adult is about adults who read children’s literature without reminiscing, for the reading experience. Nodelman looks at what the adults can find in the children’s literature and the serious intellectual ideas that are there for children to discard.

See also Literature and the Child and Give Them Wings, by Maurice Saxby. Most general books about children’s literature include a chapter about realism.

From Romance To Realism by Michael Cart was published 1996. The author is an expert in YA literature.

THE INNER AND OUTER REALITIES OF REALISM

In a binary, the two things represented each require the other. For example, evil needs good. Light needs darkness. Each defines the other.

There is an ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ reality. In realism, this idea of the inner world and outer world revolves very much around you as the reader. Whereas primary and secondary worlds are based around the text itself, inner and outer realities rely on the reader and what the reader knows about him or herself. Your inner reality is yours. No one can take it from you. Others can influence it, but only if you let them. The outer reality is anything you share with family, friends, people you know — the settings in which you find yourself, the actions that happen to you, the noises you hear, the dialogues you have with other people.

Fiction on the realism spectrum aligns the inner and outer realities and exposes them. In our real life interactions we rarely get a glimpse at the inner realities of other people because sharing inner realities depends on a lot of trust. But in a book you can share someone else’s inner reality — how they think, what they want, why they choose to do the things that they do.

THE INNER AND OUTER REALITIES OF FANTASY

In fantasy we start with the fantasy but then move strongly from the probable to the extraordinary. The extraordinary dominates. In fantasy, the inner reality is best related to the probable (primary world). The fantasy is related to the outer world.

In fantasy, a character’s outer reality is the focus of the story. A fantasy story is not so much about the actions of the fantasy world, but about the ideas that we have in our probable world. All fantasy works describe reality.

You’ll still read ‘probable’ and ‘extraordinary’ elements in a realist story, but in realism, readers will be able to imagine encountering these problems themselves. (Maintain the distinction between ‘possible’ and ‘probable’. In a realist story, something isn’t necessarily ‘probable’, but it must be ‘possible’.)

Plot

The sequence and plot structure of a realist story is pretty much the same as a fantasy story. That’s because all stories share an underlying basic structure.

The Hero

The main character is often a lonely outsider. A child hero might be new at a new school or looking for a friend or something like that. These stories are often formed around separation of some kind.

Theme

Justice is another common idea explored in realist fiction. What’s right? How do we decide what’s right? A big subset of the justice idea is, “When is it okay to lie?“

Voice

Realist stories are dramatic, but not melodramatic.

Tiff and the Trout is an Australian story set in Mount Beauty (not called that in the story). The main character’s parents are splitting up. The father is a mountain person and the mother is a beach person. This symbolises their separation and Tiff is caught between. This story is neither melodramatic nor especially traumatic. There is one moment where the mum’s new boyfriend takes her fishing. She almost drowns. Apart from that, it’s ordinary, everyday stuff but is a very good exploration and discovery of how Tiff feels, not how the parents feel. In the end Tiff must choose which of her parents she goes to live with.

Endings: There is also a reasonably positive resolution, but not necessarily happy-ever-after. Characters are able to move on.

POSSIBLE PROBLEMS WITH REALISTIC STORIES

Representation

If a reader hasn’t experienced a situation herself, the plot may feel a little bit exotic. ‘That’s not really going to happen to me’. The author can also accidentally promote stereotypical attitudes. In the case of Josie Alibrandi, it might be easy for readers to conclude, ‘This is how all people of Australian Italian background behave’. Likewise, when reading Parvana’s Journey, if would be easy to assume girls in Afghanistan are all like that.

In Looking For X, the main character’s brothers are both autistic. The girl tries to find another homeless person who witnessed something that happened so that her mother can keep the boys. Is that a little too far from a reader’s experience? Are all Canadian homeless people like this one?

Currency

When including modern slang/attitudes/brand names and so on, these things will date quickly compared to details in completely made up fantasy worlds. 15 years ago Specky McGee was a popular Australian series, but now the footballers mentioned in the stories are all retired. How current to make a realistic story? [Dated stories can make for very interesting historical documents.]

CONTROVERSIES THAT ONLY SEEM TO AFFECT REALISTIC CHILDREN’S BOOKS

How ‘problematic’ must the problem be? If a story is about sexuality or drugs or other grim realities, do the readers really need to know all about that just yet?

Perhaps this is because children tend to emulate the behaviours of viewpoint characters in books:

The findings from the study reinforce the idea that young children have an easier time exporting what they learn from a fictional storybook to the real world when the storybook is realistic. The leap from a fictional human to a real one is simply smaller than the leap from an anthropomorphic raccoon to a human.

The Empire of Effects: Industrial Light & Magic and the Rendering of Realism

Just about every major film now comes to us with an assist from digital effects. The results are obvious in superhero fantasies, yet dramas like Roma also rely on computer-generated imagery to enhance the verisimilitude of scenes. But the realism of digital effects is not actually true to life. It is a realism invented by Hollywood—by one company specifically: Industrial Light & Magic.

The Empire of Effects: Industrial Light & Magic and the Rendering of Realism (University of Texas Press, 2022) shows how the effects company known for the puppets and space battles of the original Star Wars went on to develop the dominant aesthetic of digital realism. Julie A. Turnock finds that ILM borrowed its technique from the New Hollywood of the 1970s, incorporating lens flares, wobbly camerawork, haphazard framing, and other cinematography that called attention to the person behind the camera. In the context of digital imagery, however, these aesthetic strategies had the opposite effect, heightening the sense of realism by calling on tropes suggesting the authenticity to which viewers were accustomed. ILM’s style, on display in the most successful films of the 1980s and beyond, was so convincing that other studios were forced to follow suit, and today, ILM is a victim of its own success, having fostered a cinematic monoculture in which it is but one player among many.

New Books Network

REALISM: A Discussion with William Ghosh

William Ghosh talks to Saronik about Realism, and how it can both be subtly conservative and effectively radical, depending on its use. He takes us through realist tactics in texts ranging from V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River to Virginie Despentes’s Vernon Subutex.

William Ghosh teaches Victorian and Modern literature and Literary Theory at Jesus College, University of Oxford. His first book, V.S. Naipaul, Caribbean Writing, and Caribbean Thought was published by OUP in October 2020. At present he is working on a book on the British writer Penelope Fitzgerald, and on a multimedia project about Caribbean poetry and poetics.

New Books Network

Estranging the Novel: Poland, Ireland, and Theories of World Literature

Katarzyna (Kasia) Bartoszyńska is an assistant professor of English and Women’s and Gender Studies at Ithaca College. Her research and teaching focuses on the novel form and the theories connected to it, combining a formalist investigation of textual mechanics with an interest in studies of gender, sexuality, race, and world literature. Prof. Bartoszyńska is also active in Polish-English translation. She has translated several texts by Zygmunt Bauman, including Sketches in the Theory of Culture (Polity 2018), Of God and Man (Polity 2015), and Culture and Art (2021) and is currently completing a translation of a book about Bauman’s work by Dariusz Brzeziński.

In this interview, she discusses her new book Estranging the Novel: Poland, Ireland and Theories of World Literature (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021), a comparative study of two national literatures that also makes a serious intervention into the history of the novel as a literary form.

Estranging the Novel: Poland, Ireland, and Theories of World Literature (Johns Hopkins UP, 2021) offers a new way of thinking about the development of the novel as a genre. The work pushes against the standard narrative of the novel’s rise on two fronts, arguing that the focus on Anglo-French fiction, on the one hand, and realism, on the other, gives us an overly narrow sense of the novel’s potential, and skews our readings of fiction from “other” parts of the world. Bartoszyńska uses three close readings of pairs of books from Poland and Ireland, spanning the eighteenth through the twentieth centuries, to demonstrate how mainstream theories of the novel fail to engage their most innovative features, because they do not conform to emerging conventions of realist fiction. Examining the features of these works that have been seen as deviations from the novel’s teleology, such as satire, interlaced tales, or the use of the supernatural, she presents them as efforts to theorize the potential of the form and investigates the novel’s world-building powers.

New Books Network