Metafiction is a story which draws attention to its status as a story.

In Metafiction: the Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction (1984) Patricia Waugh defines metafiction as “fictional writing which self-consciously and systematically draws attention to its status as an artifact in order to pose questions about the relationship between fiction and reality.“

“Its relationship to the phenomenal world is highly complex, problematic and regulated by convention.” (I like that phrase ‘phenomenal world’ to what I’ve always problematically referred to ‘the real world’)

Why do we need words for talking about metafiction? To distinguish between the world within fiction and the world outside it.

Although metafictional elements can be found in pretty much any work of fiction, metafiction as a literary device is relatively new in Western literature — perhaps 40 years old.

The Raison d’être of Metafiction

To create a fiction AND to make a statement about the creation of that fiction.

Two Main Types of Metafiction

- Metafiction which parodies a well-known work of literature

- Metafiction which reminds the audience they are experiencing a work of art (instead of immersing them in verisimilitude).

Metafiction is prevalent in experimental post-modern literature, but shouldn’t be regarded as only an experiment for experiment’s sake.

The message of a metafictional story is often that the world itself is artificial, constructed, man-made. It asks the question: What is the boundary that delimits fiction and reality?

In books for young readers, polyphony is one example of a metafictive device. Polyphony is “multi-voicedness”.

Metafiction isn’t a genre. It’s a trend within a genre. It’s a literary device, or a combination of literary devices which establish a certain dynamic between storyteller and audience.

Metafiction And Children’s Literature

Metafiction has been around in literature since the 1600s, but metafiction in children’s literature started to take off from the 1980s. Metafiction is commonly utilised in what we now call Postmodern literature.

Metafiction in children’s books looks a bit different from metafiction in books for adults. This is because metafiction always relies on past experience of the reader. Young readers don’t bring as much life experience to a work.

In children’s literature, metafiction is sometimes obvious to both child and adult co-reader, but often it is obvious only to the adult co-reader, resulting in a story which can appeal to a dual audience.

Daniel Handler is a tentpole example of a modern metafictive children’s author. His books are written by ‘Lemony Snicket‘, and he even continues this gag with him to his stage presentations. Adult readers know that the Series Of Unfortunate Events wasn’t written by one of the characters from inside, that a publishing world exists, with a real-world author behind the name. As for picture books, Mo Willems regularly utilises metafictive devices.

A Pack Of Lies (1989) by Geraldine McCaughrean is an outstanding example of middle grade metafiction.

Ailsa doesn’t trust MCC Berkshire, the mysterious man helping out in her mother’s antique shop. He tells wonderful stories about all the antiques, and his stories persuade the customers to buy the items he talks about, but everything he says is a pack of lies. Isn’t it?

The story of Ailsa and MCC is interwoven with the stories MCC tells the customers, which range from romances to adventure stories; from crime dramas to pirate stories; from stories set in modern-day Ireland to stories set in ancient China.

MARKETING COPY FOR A PACK OF LIES

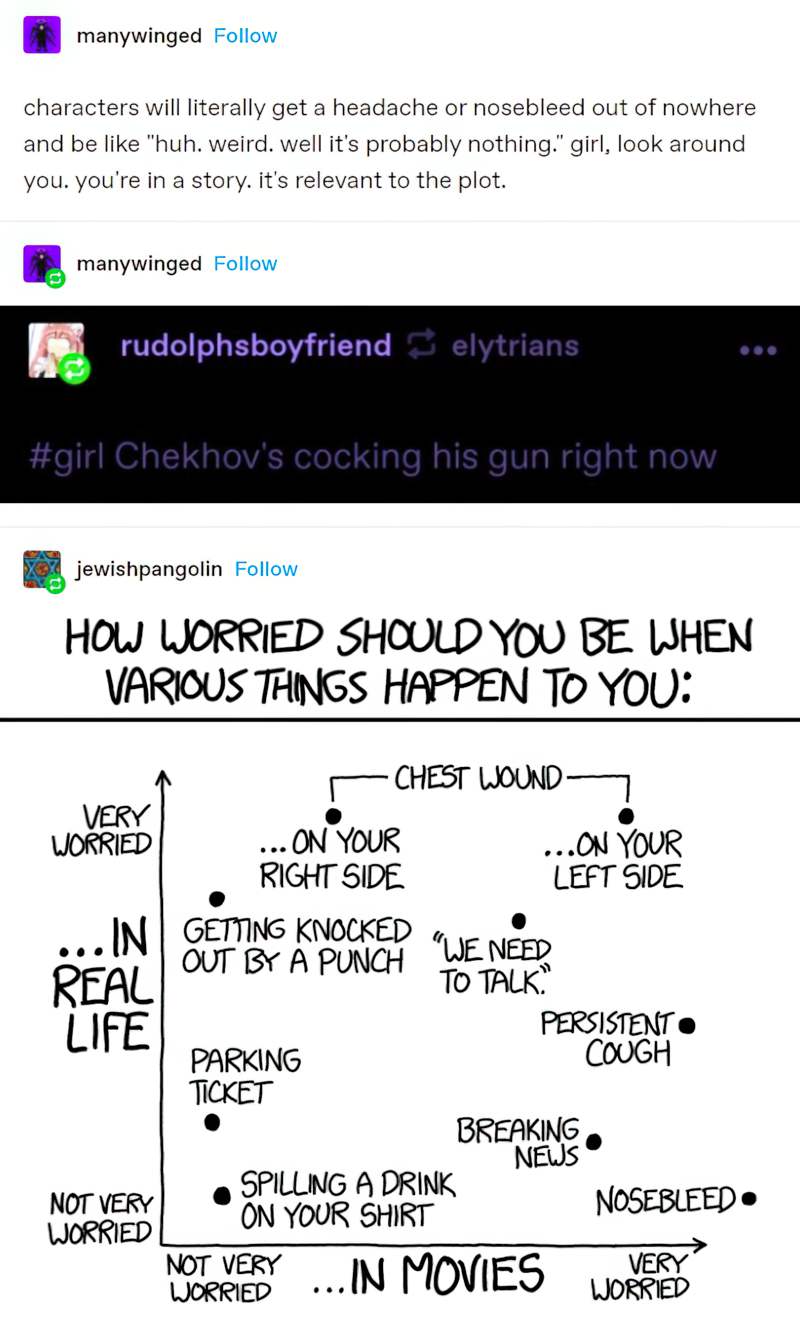

Sometimes, a metafictive take isn’t encouraged until the end of the story. Fade by Robert Cormier and Freaky Friday by Mary Rodgers might be considered metafictive because their endings make the reader wonder how much of the story is supposed to be true.

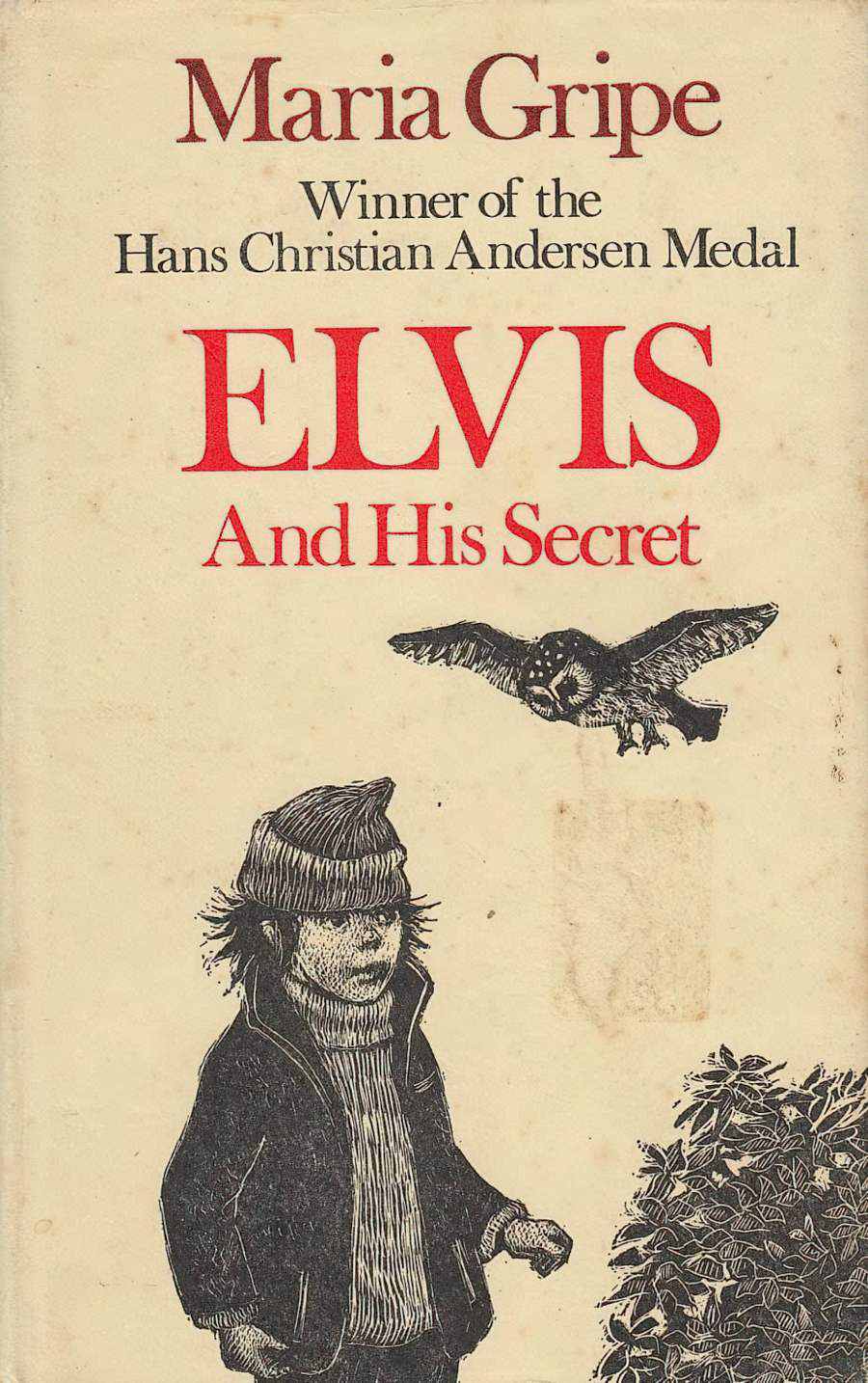

Directly addressing the reader (or breaking the fourth wall) is a metafictive device. Maria Gripe used it in her books about Elvis, and it has been developed by many modern Scandinavian children’s writers in particular.

The Monster At The End Of This Book is an example of breaking the fourth wall for young readers. (You can read that here.) Grover speaks directly to the reader, and the book appears to us as an artifact in the space between phenomenal world and fictional world. (The pages can be boarded up, nailed together.) Another more contemporary picture book which also turns the book into a real but fictional object is This Book Just Ate My Dog by Richard Byrne.

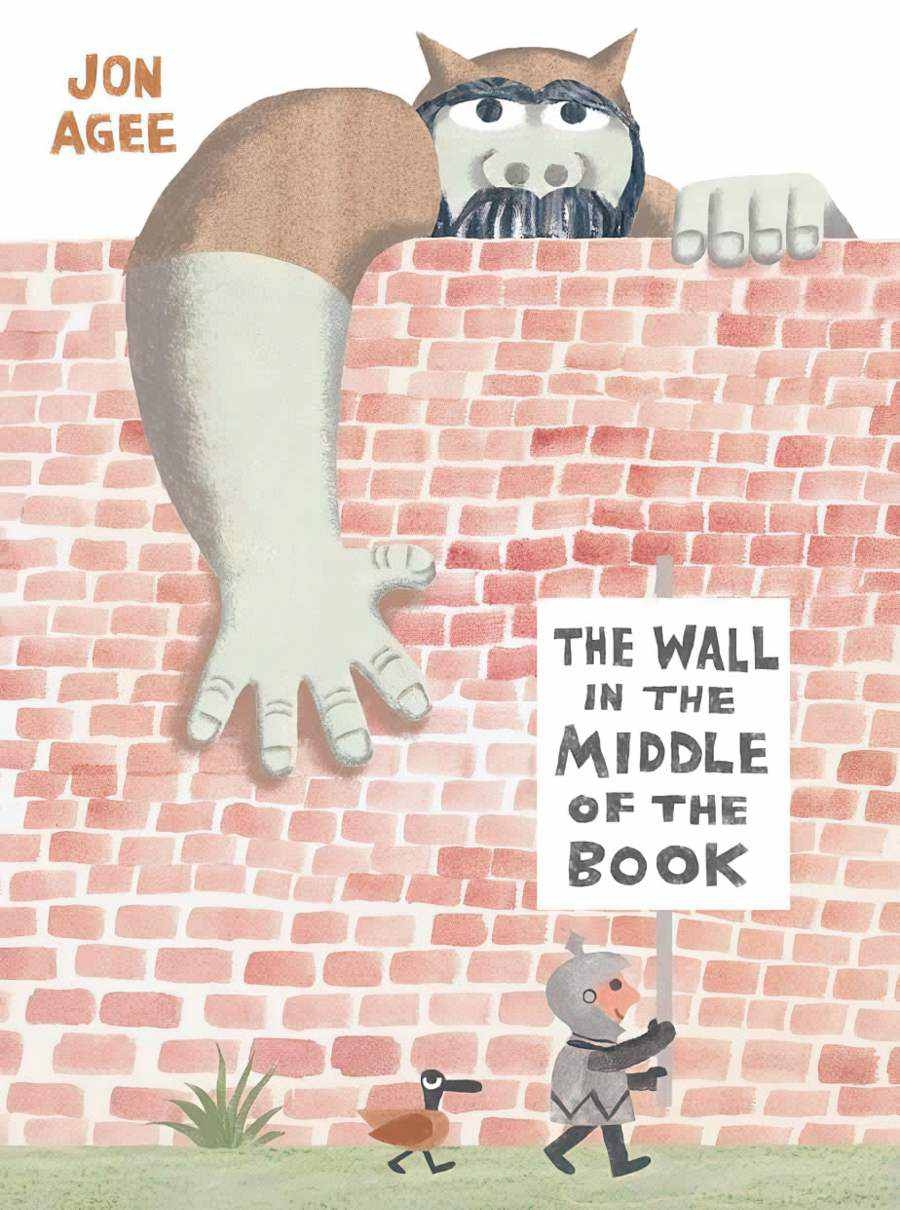

A foolish knight is certain that his side of the wall is the safe side in this meta picture book.

There’s a wall in the middle of the book, and our hero—a young knight—is sure that the wall protects his side of the book from the dangers of the other side—like an angry tiger and giant rhino, and worst of all, an ogre who would gobble him up in a second! But our knight doesn’t seem to notice the crocodile and growing sea of water that are emerging on his side. When he’s almost over his head and calling for help, who will come to his rescue? An individual who isn’t as dangerous as the knight thought—from a side of the book that might just have some positive things to offer after all!

The Implied Writer, Implied Reader, Real Reader and Narrator

A metafictional work has: the writer (e.g. Daniel Handler), the implied writer (e.g. Lemony Snicket), the narrator (the “I” of the novel), the implied reader (“you”) and the real reader. Other (non-metafictional) works might have the writer, the narrator and the reader. Simple.

As long as anything can happen in a book it can also happen in real life, since it always happens more in real life.

Tormod Haugen

Is Fantasy Always Metafictive?

We might argue that adult fantasy is by default metafictive, since the reader is aware of entering a different kind of world. But in children’s fantasy, that awareness is not necessarily there on the part of the child reader, so it’s hard to argue the same case.

Metafiction Exists On A Spectrum

Let’s move away from a binary notion of metafiction wherein one work of literature is metafictive while another is not. Think instead of a spectrum. The degree of metafictiveness of any given work will depend not only on the number of metafictive devices utilised by storytellers, but also upon how any given member of the audience interacts with that work.

One reader might have a metafictive experience while another is fully immersed. This is especially relevant when it comes to children’s literature, because an adult may have a metafictive reading experience while the child reader is engaged in ludic reading.

‘Ludic’ or ‘absorbed’ reading is a virtually trance-like state in which readers willingly become oblivious to the world around them. The term as used here comes from Hugh Crago and Victor Nell.

POETRY

Poetry, unlike music, is a meta-art, and relies upon non-physical structures for the production of its effects. In its case, the medium is syntax, grammar and logical continuity, which together form the carrier-wave of plain sense within which its deeper meanings are broadcast.

Don Paterson, The empty image: new models of the poetic trope (Is it possible that all children’s verse is a meta-art, simply because the language draws attention to itself?)

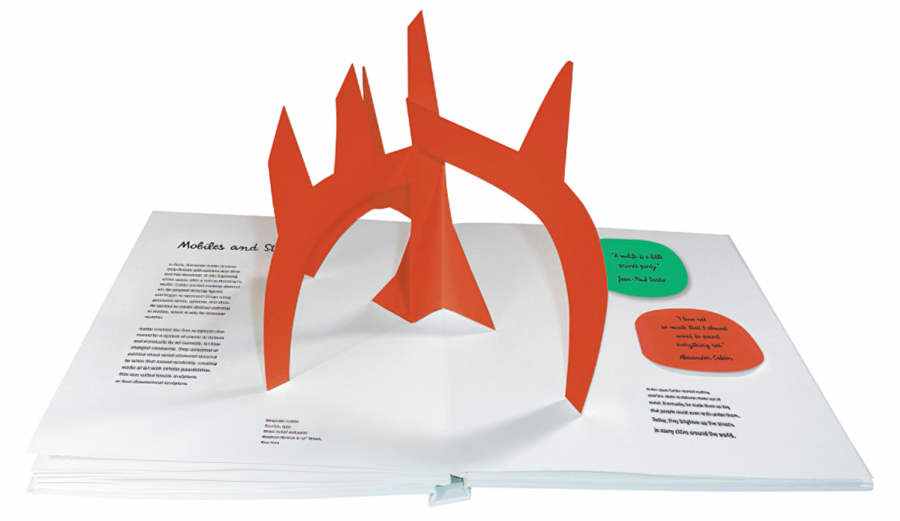

POP-UP BOOKS

What about a pop-up book, in which the card moves, drawing the reader’s attention to the workings of the book? Is it possible to read a pop-up book and be so immersed in the story that you don’t really notice the engineering of the paper?

ARE INTERACTIVE STORIES INHERENTLY METAFICTIVE?

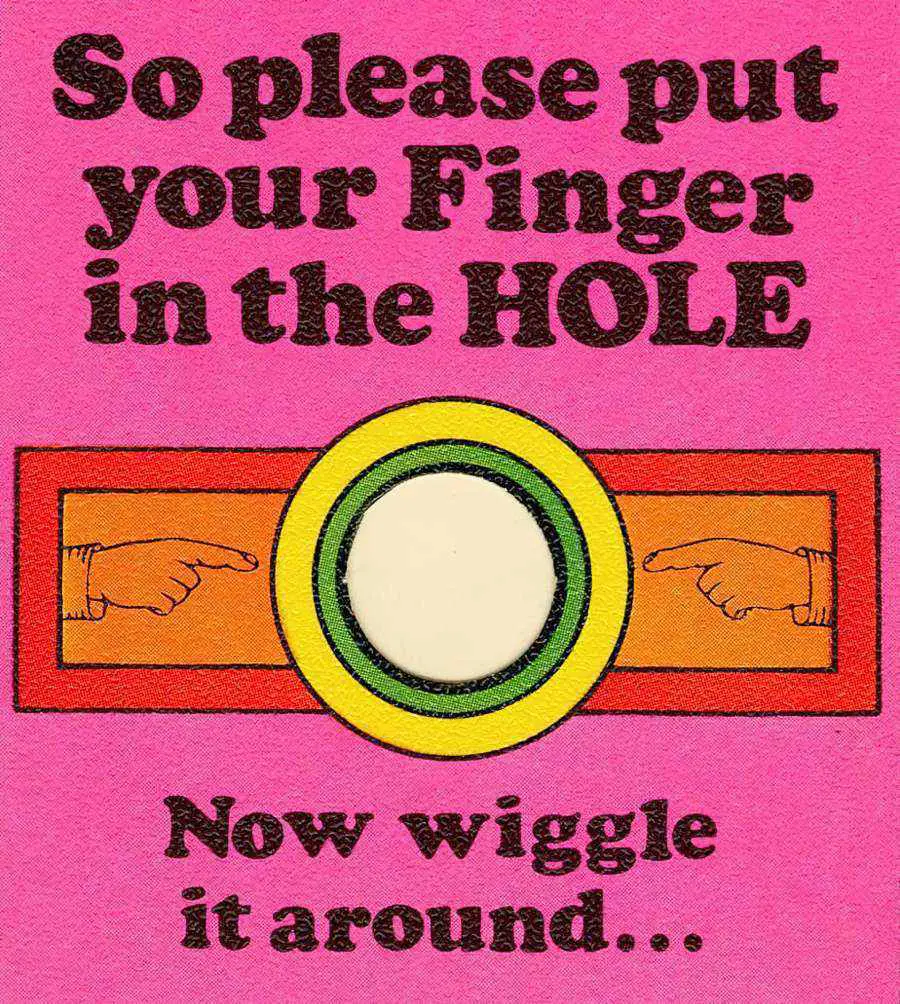

Interactivity existed in picturebooks before digitization came along:

- pop-outs

- movables

- scratch-and-sniff hot spots

- mazes

- choose-your-own-adventures

- musical chips

- flashing light-emitting diodes

- fold-out flaps

- holograms

And here is a list of very inventive books published 2013, each making use of an unusual arrangement of board/paper and so on.

In his book Reading Contemporary Picturebooks, David Lewis offers a brief list of some landmark examples of interactive printed picturebooks:

- The Spot books by Eric Hill

- Jan Pienkowski’s elaborately engineered works of art (e.g. Haunted House, Robot)

- Eric Carle‘s books, with their cut and shaped pages

- Much work of the Ahlbergs (Peepo, The Jolly Postman, Yum Yum and Playmates)

- Making Faces by Nick Butterworth, which includes a mirror in which the reader makes faces

- Tom’s Pirate Ship by Philippe Dupasquier, a ‘spot-the-difference’ book

- Say Cheese by David Pelham, a pop-up book shaped in three dimensions like a wedge from a circular block of cheese

- Where, Oh Where, is Kipper’s Bear? by Mick Inkpen, containing a tiny torch that lights up at the end of the book.

David Lewis also argues a case for interactions in picturebooks being inherently metafictive in that they inevitably bring readers out of the story itself:

Books such as these … foreground the nature of the book as an object, an artefact to be handled and manipulated as wella s read. They are thus metafictive to the extent that they tempt readers to withdraw attention from the story (which, it must be said, is often pretty slender) in order to look at, play with and admire the paper engineering. One of the characteristics of a well-told tale is that as we read it our awareness of the book in which it is written tends to fade away, but when the material fabric of the book has been doctored in such a way as to draw attention to itself, it is less easy to withdraw into that fictive, secondary world.

Ultimately, Lewis considers interactive picturebooks as valid artifacts in their own right — a cross between books and toys:

Pop-ups and movables tend to produce a degree of unease amongst children’s book critics and scholars for they often do not seem to offer much in the way of a reading experience at all. For this reason they are sometimes considered to be more like toys than books, objects to play with rather than to read. There is some justice in this view, but it is far too simplistic for it tidies up too neatly something that, if we are honest, rather resists pigeonholing. We might better understand the world of the movable if we view it as a hybrid, a merging of two, otherwise incompatible artifacts: the toy and the picturebook.

I would argue instead that interactiions in picturebooks (whether printed or digital) come in various forms, and can be manipulated by careful developers to either pull readers out of the story or to draw them in deeper. Interactions are therefore not necessarily metafictive.

FURTHER READING

Bridget from A Very Curious Blog points out that:

It’s harder (but not impossible) to find metafiction in intermediate and young adult fiction. Would Dianne Wynne Jone’s The Dark Lord of Derkholm count? How often do characters in a book reveal the fact that they know they are characters? And how do young readers respond to this revelation?

Bridget also links to a video by Philip Nel called Metafiction For Children, in which we are warned not to call this trend ‘Postmodern’ because metafiction has been around since the early 1600s. It is also pointed out that ‘a metafictional book can also be interactive’, though I would go one step further (actually I have) and ask if not all interactive books (and therefore book apps) are metafictive precisely because interaction requires the reader be pulled out of the story and into the ‘mechanics’ of the printed book or software.

Suggestions in the comments section of the above video lead to a list: More Metafiction For Children.

Metafictional picturebooks from Book Riot

Meta Children’s Books from Romper

Maria Nikolajeva’s Children’s Literature Comes Of Age and The Rhetoric of Character in Children’s Literature.

Metafiction: the Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction (1984) by Patricia Waugh

Header photo by Frank Okay