This is the most succinct explanation of magical realism that I have seen lately:

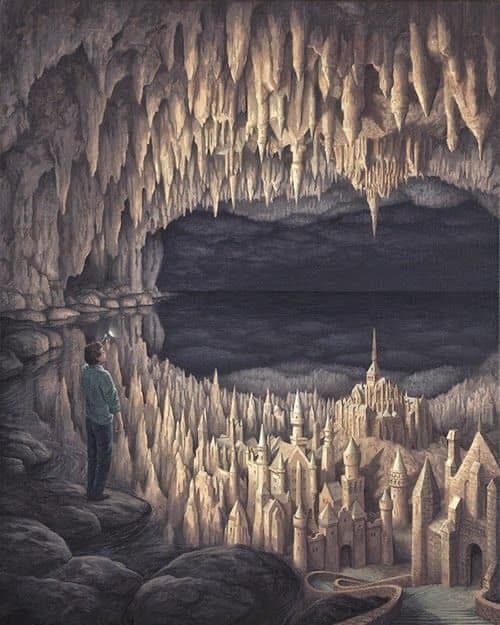

Magical realism is when the world is about 95% normal, but 5% magical/mystical and that magic is a totally natural part of the world.

@MadmoiselleClel (Clelia Gore on Twitter)

This is from Abrams:

Magic realism, a literary genre strongly associated with contemporary Latin American writers, “interweaves, in an ever-shifting pattern, a sharply etched realism in representing ordinary events and descriptive details together with fantastic and dreamlike elements”

M.H. Abrams

Note that magical realism is a literary term, and not necessarily all that useful for authors.

Helen Oyeyemi is a British novelist. She lives in Prague with an ever-increasing number of teapots, and has written nine books so far, none of which contain ‘magical realism’. (Can’t fiction sometimes get extra fictional without being called such names?!)

Helen Oyeyemi’s biography on Goodreads

But if you write an ‘extra fictional’ book and try to find a literary agent, you will find many agents and editors asking for magical realism in children’s books at the moment. They complain that they’re not getting enough of it. When an author says, “Hey I’ve got some for you!” apparently it’s not the agent’s idea of magical realism at all.

The characteristics as listed by Wendy B. Faris are sometimes used by academics:

Wendy Faris’s Five Characteristics of Magical Realism

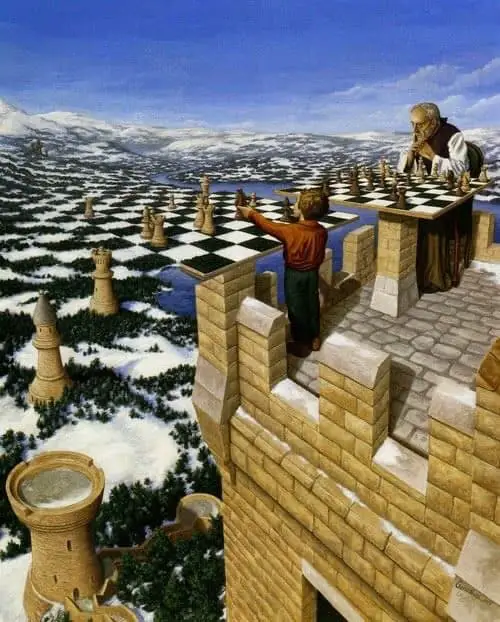

- An irreducible element of magic;

- A grounding in the phenomenal world, i.e., the realistic world;

- The production of unsettling doubts in the reader because of this mixture of the real and the fantastic;

- The near merging of two realms or worlds; and

- Disruptions of traditional ideas about time, space, and identity

Agent Michelle Witte has (used to have?) a much more detailed series of blog posts defining exactly what magical realism is and is not.

Essentially, magical realism is:

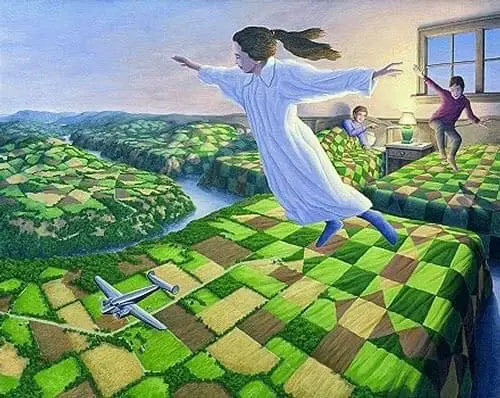

Real-world setting + fantastical elements = magical realism

In visual terms, think of it as a photo that’s blurred around the edges to give it an ethereal, almost otherworldly quality. It has the feel of magic—that anything is possible.

Magical realism focuses on ordinary people going about the humdrum activities of daily life. Everything is normal—except for one or two elements that go beyond the realm of possibility, whether it be magic or fate or a physical connection with the earth and the creatures that inhabit it, but always in a way that celebrates the mundane.

FABULISM OR MAGICAL REALISM?

The definition of magical realism varies, depending on who you ask. Here is another point of view:

Michelle Witte argues that in fact magical realism did not originate in South America:

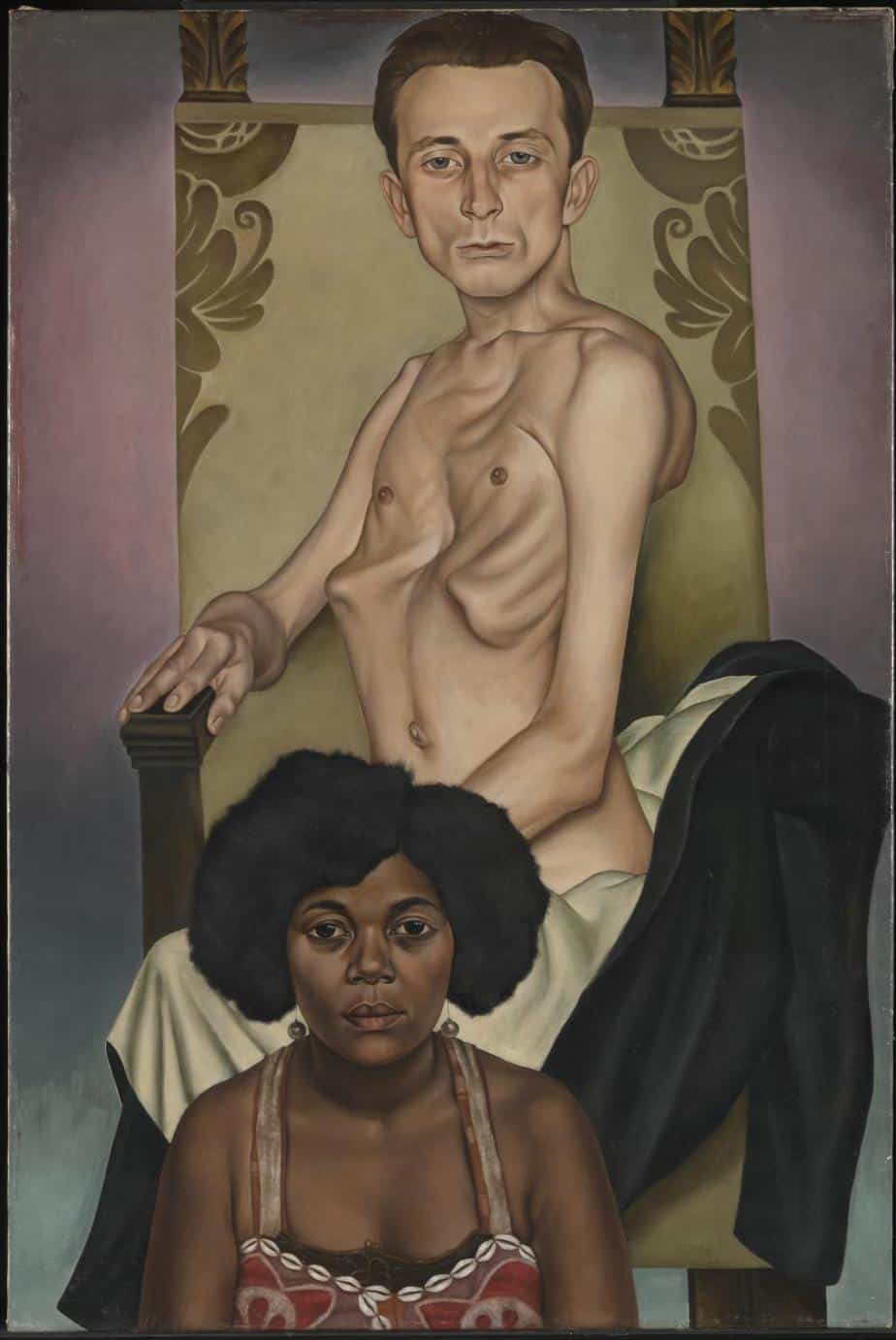

Despite the common misconception, magical realism didn’t originate in South America. Instead, German art critic Franz Roch coined the term “magical realism” in 1925 to describe the New Objectivity style of painting. A few years later, the concept of magical realism crossed the ocean to South America, where it was adopted and popularized by Latin American authors throughout the twentieth century as lo real maravilloso, the marvelous real. Notable writers include Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and Isabel Allende, among numerous others.

While Hispanic writers were—and still are—a major influence in modern magical realistic literature, the style is not limited to a specific time or place. In fact, writers from across the world have adopted and adapted magical realism to fit their own cultures and within their own frame of reference.

ENCHANTED REALISM

Sheila Egoff writes of ‘enchanted realism’, which avoids the problem nicely. Enchanted realism is a genre of children’s literature that

gradually penetrates the imagination blending fantasy and reality through a distortion of time and space

As examples she offers

- The Children of the Green Knowe (1954) by Lucy Boston

- Tom’s Midnight Garden (1958) by Philippa Pearce

- Tuck Everlasting (1975) by Natalie Babbitt

What’s the difference between these stories and plain old fantasy?

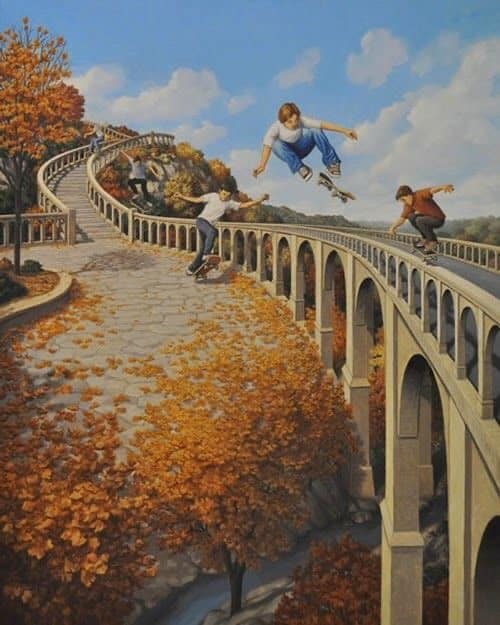

The worlds are integrated into the real world, unlike, for instance, the world of Narnia, which is entirely separated from our real world via the portal of a wardrobe. Instead, the real world becomes enchanted within a confined arena such as:

- an ancient house

- a small village

- a garden

- a nearby wood

Such enchanted places are liminal spaces. The child character isn’t sure where the real world ends and the enchanted world begins. This arena provides a place for the child to explore and transform (have a character arc).

Egoff writes than in earlier works of enchanted realism:

childhood is seen as a state separate from adulthood and the adventures the children encounter are a product of their own devising, their own serious play and imaginings

SEE ALSO

Fifty years on, One Hundred Years of Solitude is still providing profound insights into our evolving human tale where horrors co-exist with wonders, where absurdities don’t provoke a blink.

One Hundred Years of Solitude is 50. Its magic realism is immortal, from Scroll.in

- This Vox article does a great job of summarising the debates around the term magical realism, and who may use it.

- Here’s a list of magical realist children’s books, which I am calling ‘fabulism’ to be safe: Fabulism In Children’s Literature