According to a large portion of the world’s population, humankind is already living in a dystopia.

The fun part about living right now is we get to see how it ends.

@meganamram

A great civilisation is not conquered from until it has destroyed itself from within.

APOCALYPTO (Mel Gibson, 2006)

Anderson Cooper conducted an interview with Israeli historian and bestselling author Yuval Noah Harari in which he admitted to being frightened by his predictions about the future of humanity.

At the start of the interview, Cooper quoted Harari’s claim that humans alive today will be “one of the last generations of homosapiens” and that “within a century or two, Earth will be dominated by entities that are more different from us than we are different from chimpanzees.”

“Yes,” Harari replied.

Raw Story

In Living in the End Times [Slovenian philosopher] Slavoj Žižek has argued that under the conditions of late capitalism, catastrophe ‘is renormalized, perceived as part of the normal run of things, as always already having been possible’. In the wake of the recent ‘war on terror’ he argued that before 11 September 2001 (or 9/11) the use of torture was ‘dismissed as an ethical catastrophe’ but that ‘once it happened, it retroactively grounded its own possibility, and we immediately got accustomed to it’. Fictional accounts of the apocalypse can also work as reminders that what is presented as a feature of a future society is already an established fact of its extra-textual reality and already present in the form of accepted beliefs and ideologies.

Landscapes of loss: the semantics of empty spaces in contemporary post-apocalyptic fiction by Martin Walter, from the book Empty Spaces: Perspectives on emptiness in modern history, 2019

Dystopia and The Bible

Ever since God punished Adam, Eve and the serpent for eating from that tree we have been banished from Paradise. Compared to Paradise, this toiling, this painful childbirth, these thistles and weeds growing up through our crops are considered part of this Earthly dystopia — a temporary punishment before taking up residence in Paradise once more in the after life.

If not taken literally by so many today, Earth as a dystopian setting was certainly literal for earlier peoples from the major religious traditions (and I’m guessing we’ll get there again).

Although dystopia seems to be the opposite of idyll, it has in fact the same purpose: to conserve the children—as well as adults—in an innocent, unchanging state, comfortably freed from memories, emotions, affections, responsibilities—and from natural death. Breaking away from a safe and secluded dystopian society, children break out into linearity.

Maria Nikolajeva, From Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature

Nikolajeva goes on to explain that quite a few authors depict a reverse process, and offers A Cry from the Jungle by Norwegian author Tormod Haugen as an example of an ‘extremely complicated and equivocal novel.’

Take it. Live it. F*** it.

A new drug is out. Everyone is talking about it. The Hit. Take it, and you have one amazing week to live. It’s the ultimate high. At the ultimate price.

Adam is tempted. Life is rubbish, his girlfriend’s over him, his brother’s gone. So what’s he got to lose? Everything, as it turns out. It’s up to his girlfriend, Lizzie, to show him…

The Hit is an irresistible celebration of teenage kicks. It describes a group of teenagers indulging their wildest desires, going all out to do the things they’ve always dreamed of, because, in a joyless, repressive, recession-hit society of the future, they’ve taken Death, a new drug that will kill you in exactly seven days, but make sure that those seven days are the best you could ever experience.

It’s a brilliant idea, and you wonder if anyone but Burgess could have done it justice. His hero, Adam, draws up a bucket list that includes ‘loads of sex with loads of girls’ as well as ‘do something so that humanity will remember me for ever’.

Melvin Burgess Interview at Books For Keeps

Features Of Dystopian Fiction

Young adult dystopia, especially, is very faced past. Stories open with the main character experiencing end-of-the-world disaster. Readers who enjoy fast pacing are therefore drawn into dystopia, perhaps not for the dystopian world but for the pacing.

See also: Talking About Story Pacing.

Characters in a dystopian plot start from a position of entrapment.

In dystopian novels, the main character usually rebels against the status quo by exposing its flaws, escaping the world entirely, attempting to take it over, or initiating a new set of rules.

Dystopian stories often take place after a large societal restructuring, usually because of a global event. In this way they might seem post-apocalyptic, but when the conflict of a story focuses on the oppression of a government or set of ideas, rather than on the direct consequences of a wide-spread tragedy, it is dystopian.

Dystopian novels often focus on societies and cultures that appear stable and well established, whereas post-apocalyptic cultures are more imbalanced or volatile.

What Type Of Setting Is Typical In Dystopian Fiction?

Writers of dystopian fiction have a dilemma:

If the setting is too far removed from reality, readers will feel comfortable, with no impulse to be alarmed and act in the real world. These stories function as fun and cathartic reads with a reduction in anxiety. These stories can reinforce smug assumptions of safety — “This is pure fiction. Our world could never disintegrate like this.”

If the dystopian world of fiction is too close to reality, readers may be repelled and anxious, and not make it to the end.

So dystopian settings tend to walk a delicate area between these extremes, and are set in a recognisable yet significantly different world from the day-to-day life of readers.

A Brief History Of Dystopia

The first public usage of the word ‘dystopia’ goes all the way back to John Stuart Mill in 1868. In a speech to the House of Commons, Mill said, “It is, perhaps, too complimentary to call them Utopians, they ought rather to be called dys-topians, or caco-topians” (‘cacotopia’ was relegated to the Wastepaper Basket of History). But it wasn’t until about 50 years afterward, when authors made the word their own, that the idea of dystopia began to actually take root in the public consciousness.

Electric Literature

In the late 20th and early 21st century, dystopian fiction has seen a huge resurgence in popularity. Some commentators believe there is so much dystopian entertainment that the impact is now lost. Tentpole examples include:

- Independence Day (1996) — apocalyptic disaster movie

- Resident Evil (1996-) — a video game franchise

- Armageddon (1998) — science fiction disaster film produced and directed by Michael Bay

- The Day After Tomorrow (2004, 2009, 2012) — disaster film

- War of the Worlds (2005) — remake of a much older radio play

- The Road (2006) — based on the book by Cormac McCarthy. A father and son travel through an empty, corpse-ridden America after an unnamed disaster which has plunged the world into winter.

- The Carhullan Army (2007) — Sarah Hall, ecofeminist climate fiction which explores the consequences of climate change in post-oil Britain.

- District 9 (2009)

- The Walking Dead (2010-) — a graphic novel and popular TV series with zombies

- The Book of Eli (2010) — a dystopian, anti-Western genre blend, film

- The Passage (2010) by Justin Cronin. Post-apocalyptic vampires.

- The Hunger Games series (2012-15) — a hugely popular YA series by Suzanne Collins which became a series of films

- Falling Skies (2011-15)

- World War Z (2013) — a blockbuster book and film

- Interstellar (2015) — a crossover science fiction film

- Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) — post-apocalyptic action blockbuster which grossed over $375 million.

Dystopia and Young Readers

According to a new report, Australian kids are feeling pessimistic about their own futures, and this goes against evidence. Australian kids should be feeling pretty good about the future, according to one expert. (Not sure I agree personally, given the climate emergency, which overshadows everything else.)

Key points from the radio interview:

- Youth unemployment has been higher in the past, and is reflecting that it takes time to find their way into the job market, as unemployment goes down as job seekers get older. This is reflected in other countries. Southern European unemployment rates for youth (especially Southern Italy and Spain) is much more bleak.

- Why are young Australian people pessimistic? It is thought that young Australians have unrealistic expectations about what to expect from a first job. In Brazil, China and countries like that have youth with lower expectations and are therefore more optimistic.

- Older people need to tell young people what their own paths to success have been.

- The media also has a part to play. We’ve seen processing plants closing down, but we don’t see the steady flow of new job opportunities coming through the news. The small trickle more than offsets the big closures. (Audiences are after bad news, and the media cater to that.)

- The number of law graduates each year far exceeds the number of places available. Law is ‘the new arts degree’. It’s true that law graduates are still useful in the workplace even if they are not practising law, but are young law students given a realistic idea about what percentage of graduates will find jobs as lawyers? Law graduates are not expensive to produce for universities. It’s book learning so they are cheap to train. Universities are following a good economic pattern, but at what cost for the 18 year olds enrolling in these degrees, which are quite expensive for them? (Or perhaps law students are more expensive to train than we assume.)

- IT students are equally pessimistic as law students. Private providers are competing with the universities in IT, moving into computer science, which is quite distinct from being able to program. The ability to successfully adapt different technologies in work environments, they are the crucial skills. Just being able to code in a particular language isn’t much use. Australia is good at having the bright idea and being able to adapt the bright idea in a business context.

- Where is the pessimism coming from? The negativity from politicians doesn’t help. Universities haven’t been very good at making their graduates work-ready.

- We need to change the nature of internships and cadetships, which currently accept large numbers of graduates but at the end of that period only one in sixty (for example in finance) will be offered a job at the end of it. This turns the whole thing into a bit of a waste of time for the other 59. Internships need to go hand-in-hand with study. Companies need to work more closely with degree programs to prepare students for the workforce.

Where else might youth pessimism be coming from? Is it limited to ‘pessimism about work’ or pessimism about the environment, politics and society in general? Could youth pessimism also be to do with the stories that are popular for young people? Today’s young people have grown up in the Third Golden Age of Children’s Literature, and this is an age rife with dystopias. There have been so many dystopias in fiction that if you listen to what agents and publishers are looking for in the kidlit-o-sphere you’ll hear a lot of publishing professionals say they are sick to death of them and are looking for something completely different.

Here in Australia, parallel importing and the Hollywood trend of adapting best-selling YA books to film has changed the Australian reading landscape over the past 15 years to point where the top-selling books are mainly from America.

Insofar as best-selling books corresponds to library lending rates (which are very easy to find), here are Australia’s library lending stats for YA last year:

The most borrowed young adult fiction titles were:

- Hunger Games series by Suzanne Collins (American/science fiction adventure)

- Divergent series by Veronica Roth (American/science fiction adventure)

- The Fault in Our Stars by John Green (American/romance)

- The Book Thief by Marcus Zusak (Australian/Holocaust)

- Looking for Alaska by John Green (American/romance)

- Percy Jackson series by Rick Riordan (American/fantasy adventure)

- The Maze Runner by James Dashner (American/science fiction)

- Every Breath by Ellie Marney (Australian/thriller)

- An Abundance of Katherines by John Green (American/romance)

- Mortal Instruments series by Cassandra Clare (American/fantasy adventure)

Teen borrowers from Australian libraries [are] looking for a blend of escapism and realism. Gritty romances, fantasy and adventure were the main themes, with all but two of the list coming from American writers.

Australia’s Favourite Library Books

American Apocalyptic Fiction

Lee Quinby wrote an essay called “Demurring to Doom: The Geopolitics of Prevailing” about a particularly American view of end-of-times, dividing evil broadly into:

- Human e.g. Dr Octopus in Spider-man. These stories tend to be about one man’s evil. This story is entrenched in American narrative.

- Social — Evil exists within a human-made framework of social injustice. Far less explored.

- Cosmic/apocalyptic e.g. Terminator. Entrenched.

Revenge and doom loom large in categories one and three.

Quinby advocates for a shift in how American stories present evil, hoping to shift audiences towards a vision of themselves as global citizens, ‘interconnected with all of humanity and interdependent in the world we live in together.’

What Is Apocalyptic Fiction?

- Apocalypse fiction is generally melodrama. (That word as used in literature may not mean what you think it means.)

- An apocalyptic novel tells the story of the end of the world, which occurs during the timeline of the story.

- In almost all apocalyptic stories life is threatened on a global scale: disease, natural disaster, war, or alien invasion, for example.

- Entire cities tend to be destroyed, which opens up these spaces in preparation for rebuilding. Many apocalyptic stories are about an ending, not the end of the world.

- Destroyed cities are both familiar and unfamiliar, which makes them excellent examples of The Uncanny as described by Sigmund Freud. Familiar sights and sounds increase the feeling of unease.

- When familiar buildings and cities are destroyed, inhabitants utilise space in new ways. Extra space leads to problems experienced by our ancestors, for example communication between separated humans is now a problem again.

- Empty corners of the city, large plains (where you can be easily seen by predators) and abandoned buildings (where opponents can hide before pouncing) are especially scary. Audiences are constantly reminded that the the familiarity of spaces has been disturbed. In movies and TV shows, aerial shots help convey this new sense of space and emptiness.

- Strangers, even (especially?) strange humans are now a danger. Communities become tribal. This is more akin to ancient ways of living, in which other humans were our biggest threat. Modern city life has made us comfortable with encountering strangers every day, but this hasn’t always been the case. In apocalyptic fiction, cities are the scary places because this is where you’re likely to encounter unknown humans. Threats originate from the city. (In The Walking Dead, humans are more deadly than the zombies.)

- Apocalyptic fiction often makes use of Western iconography. There’s often a modern take on the ‘wagon train sagas beset by swarms of attacking Indians’ (as G. Desilet puts it in Screens of Blood: A Critical Approach to Film and Television Violence, 2014).

- The characters facing an apocalypse must try to outlive, outlast, or outsmart the hazards of a crumbling world, which is made increasingly unlikely when the majority of the population has fallen victim.

- Characters are constantly striving to regain what they had in the beforetimes.

- It is common for apocalyptic novels to classify as “genre,” because the survival conflict is at the forefront of the story, making apocalyptic stories more plot driven than character based.

- If characters return to their former home, this is often seen as meaningless. Home is no longer what it once was. Humans must find a new home. Frequently, though, each new base comes under threat, and the overall message of these stories is that there is no such thing as home. The only thing to do is keep moving. In The Walking Dead this is a constant pattern. Characters find ‘new homes’ already inhabited, and go back to their lives as constant roamers.

- Post-apocalyptic fiction tends to say something about neoliberal society. In both, everyone has to make their own capital and become the entrepreneurs of themselves.

- Security and surveillance is also a common theme, because characters are constantly on the lookout for threat.

- The main goal of human characters living in apocalyptic stories: Accurately predict the next threat and avoid anyone violating your own body.

- Since the beginning of capitalist industrialization, humans have been mass-migrating from rural areas to cities. The post-apocalyptic story reverses this trend. This time, the cities become abandoned wastelands, not the regional towns. Reverse industrialization.

Apocalypse stories tend to coincide with the perceived endings of eras.

Centuries were an early modern invention, and it was only the end of the 19th that had attracted any special attention. Undeterred by his findings (or lack of them) he nevertheless concluded that there is ‘a widespread demotic sense that the end of a calendric term somehow coincides with the end of an era, a culture, a civilisation’. Believing that ‘apocalypse is about the world’s progress to an appointed end,’ he fell back on the idea of talking about apocalypse instead. The result is an engaging and fast-moving survey, but the easy slide from fin de siècle to apocalypse is one that deserves closer examination.

Malcolm Bull, The Guardian

Post-Apocalyptic

After the zombies or super flu or nuclear war, the characters left to deal with the consequences are in a post-apocalyptic story. There are numerous examples: Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, I Am Legend, and the recent Station Eleven, The Dog Stars, and The Dead Lands all tell stories about people navigating a new and hostile world. The central conflict for characters in a post-apocalyptic story is managing the new physical, social, and cultural landscape left behind by a recent disaster. There are often fewer people and less established societies in post-apocalyptic novels, so the central conflict in these stories surrounds characters who are often fighting for resources or searching for other survivors.

What Is Climate Fiction? (Cli-fi)

It wasn’t until I’d got to the end of writing and illustrating Midnight Feast that this article appeared in The Guardian: Global Warming And The Rise Of Cli-Fi. I realised that what I’d written was a picturebook contribution to cli-fi.

- a sub-genre of sci-fi in which the earth’s systems are ‘off-kilter’

- sci-fi takes place in a dystopian future, whereas cli-fi is set in a dystopian present

- Describes works which set out to warn readers of possible environmental nightmares to come

- The best cli-fi novels allow us to be briefly but intensely frightened: climate chaos is closer, more immediate, hovering over our shoulder like that murderer wielding his knife.

- Unlike sci-fi, cli-fi writing comes primarily from a place of warning rather than discovery.

Literature for a Changing Planet

Why we must learn to tell new stories about our relationship with the earth if we are to avoid climate catastrophe.

Reading literature in a time of climate emergency can sometimes feel a bit like fiddling while Rome burns. Yet, at this turning point for the planet, scientists, policymakers, and activists have woken up to the power of stories in the fight against global warming.

In Literature for a Changing Planet (Princeton UP, 2022), Martin Puchner ranges across four thousand years of world literature to draw vital lessons about how we put ourselves on the path of climate change—and how we might change paths before it’s too late. From the Epic of Gilgamesh and the West African Epic of Sunjata to the Communist Manifesto, Puchner reveals world literature in a new light—as an archive of environmental exploitation and a product of a way of life responsible for climate change. Literature depends on millennia of intensive agriculture, urbanization, and resource extraction, from the clay of ancient tablets to the silicon of e-readers. Yet literature also offers powerful ways to change attitudes toward the environment.

Puchner uncovers the ecological thinking behind the idea of world literature since the early nineteenth century, proposes a new way of reading in a warming world, shows how literature can help us recognize our shared humanity, and discusses the possible futures of storytelling. If we are to avoid environmental disaster, we must learn to tell the story of humans as a species responsible for global warming. Filled with important insights about the fundamental relationship between storytelling and the environment, Literature for a Changing Planet is a clarion call for readers and writers who care about the fate of life on the planet.

New Books Network

See Also: So Hot Right Now: Has climate change created a new literary genre, from NPR

Her life by the sea in ruins, Pen has lost everything in the Earth Shaker that all but destroyed the city of Los Angeles. She sets out into the wasteland to search for her family, her journey guided by a tattered copy of Homer’s Odyssey. Soon she begins to realize her own abilities and strength as she faces false promises of safety, the cloned giants who feast on humans, and a madman who wishes her dead. On her voyage, Pen learns to tell stories that reflect her strange visions, while she and her fellow survivors navigate the dangers that lie in wait. In her signature style, Francesca Lia Block has created a world that is beautiful in its destruction and as frightening as it is lovely. At the helm is Pen, a strong heroine who holds hope and love in her hands and refuses to be defeated.

What do you think would happen in a globally warmed Earth? Do you envision a Cormac McCarthy sort of apocalypse with bands of humans turning evil? In fiction, this is pretty much a given. Could there be a brighter view? A tornado, a blizzard, a forest fire, and a hurricane are met, in turn, with resilience and awe in this depiction of nature’s power and our own.

In the face of our shifting climate, young children everywhere are finding themselves subject to unfamiliar and often frightening extreme weather. Beloved author Jane Yolen and her daughter Heidi Stemple address four distinct weather emergencies (a tornado, a blizzard, a forest fire, and a hurricane) with warm family stories of finding the joy in preparedness and resilience. Their honest reassurance leaves readers with the message: nature is powerful, but you are powerful, too. Illustrated in rich environmental tones and featuring additional information about storms in the back, this book educates, comforts, and empowers young readers in stormy or sunny weather, and all the weather in between.

Peony lives with her sister and grandfather on a fruit farm outside the city. In a world where real bees are extinct, the quickest, bravest kids climb the fruit trees and pollinate the flowers by hand.

Will Peony’s grit and quick thinking be enough to keep her safe?

A story about family, loyalty, kindness and bravery, set against an all-too possible future where climate change has forever changed the way we live.

1962, London during the Cuban Missile Crisis

What would you do if there was a real possibility that the world might end?

Ray, aware of his parents’ building worry, decides to take matters into his own hands. He builds a shelter in the woods behind his house in the hope that he never has to use it. Only to discover that someone else needs it more than he does. An American girl, reported missing, has turned up there…

Why is she hiding? And with neighbour turning against neighbour, will Ray be willing to help her?

I can remember sitting in Cambridge, Massachusetts at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, thinking that we were all going to get atom bombs dropped on us at any minute.

That didn’t happen. But I think it came pretty close. So like that, things that almost happened, but didn’t. And I’m hoping that the climate crisis, although it’s already underway, I’m hoping that it can be at least stalled enough for people to get a grip on it.

Margaret Atwood in conversation with Tim Ferriss

Some people think there is still not enough cli-fi.

Related Words

- Apocalyptic sensibility: The nature of apocalyptic thought in any given community in a specific time period. This affects the stories we get, which in turn influences a society’s apocalyptic sensibility.

- Apocalypticism: The belief that we are living in end times.

- Cocooning: The act of insulating yourself from outside threat. An apocalyptic story often has a place where characters cocoon. In The Road, the father and son come across a store of food. However, they don’t stay there. In The Walking Dead, characters have a SUV which helps the group travel across the country. In Survivors, characters use a Land Rover. (The cars say something about American car culture, and are specifically American ways of cocooning.)

- Neurotic citizen, The: Engin Isin’s term for people under the doctrine of neoliberalism and ‘incited to make social and cultural investments to eliminate various dangers by calibrating its conduct on the basis of its anxieties and insecurities rather than rationalities’. Isin proposed that so-called neurotic citizens seek absolute certainty and safety, which is actually literally impossible. Post-apocalyptic settings in fiction both reflect and amplify this need and associated anxieties.

- Terra incognita: Terra incognita or terra ignota is a term used in cartography for regions that have not been mapped or documented. In post-apocalyptic fiction, when civilisation has been razed to the ground, spaces are assumed by survivors as terra incognita, ready for regeneration. The difference is, the terra incognita of post-apocalyptic fiction bears markers of a recent past. These places tend to be uncanny because they evince both a disruption of time but also a continuity of history.

- Uncanny, The: Sigmund Freud’s term (German: unheimlich) to describe a strangely familiar situation. We are both attracted to and repulsed. Uncanniness emerges in periods of transition. When we encounter the uncanny we go through the process of ‘reality testing’, meaning reality is not real anymore. Nicholas Royle has since added that the uncanny is frequently ‘associated with an experience of the threshold, liminality, margins, border, frontiers’. Post-apocalyptic settings are uncanny.

Related Links

- Why Teens Find The End Of The World So Appealing from NPR

- Why do literary novelists love dystopia? from Salon

- A LibraryThing list of YA Dystopia

- For a different setting altogether, see my post on utopias.

- Sometimes a setting appears to be a utopia, but there is a snail under the leaf.

- The Jetsons is actually a bone-chilling dystopia: This is is not the future we want

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed by Eric H. Cline (PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS 2014), book and podcast interview

- Resisting Dystopia: Becky Chambers, Annalee Newitz at the Long Now

- Author and philosopher Phil Torres (The End) joins Cara at Talk Nerdy to talk about how eschatologies (end-of-the-world theologies), may be paving the way for a secular apocalypse, and how we can mitigate existential risk by applying scientific rigor to these big-picture philosophical quandaries.

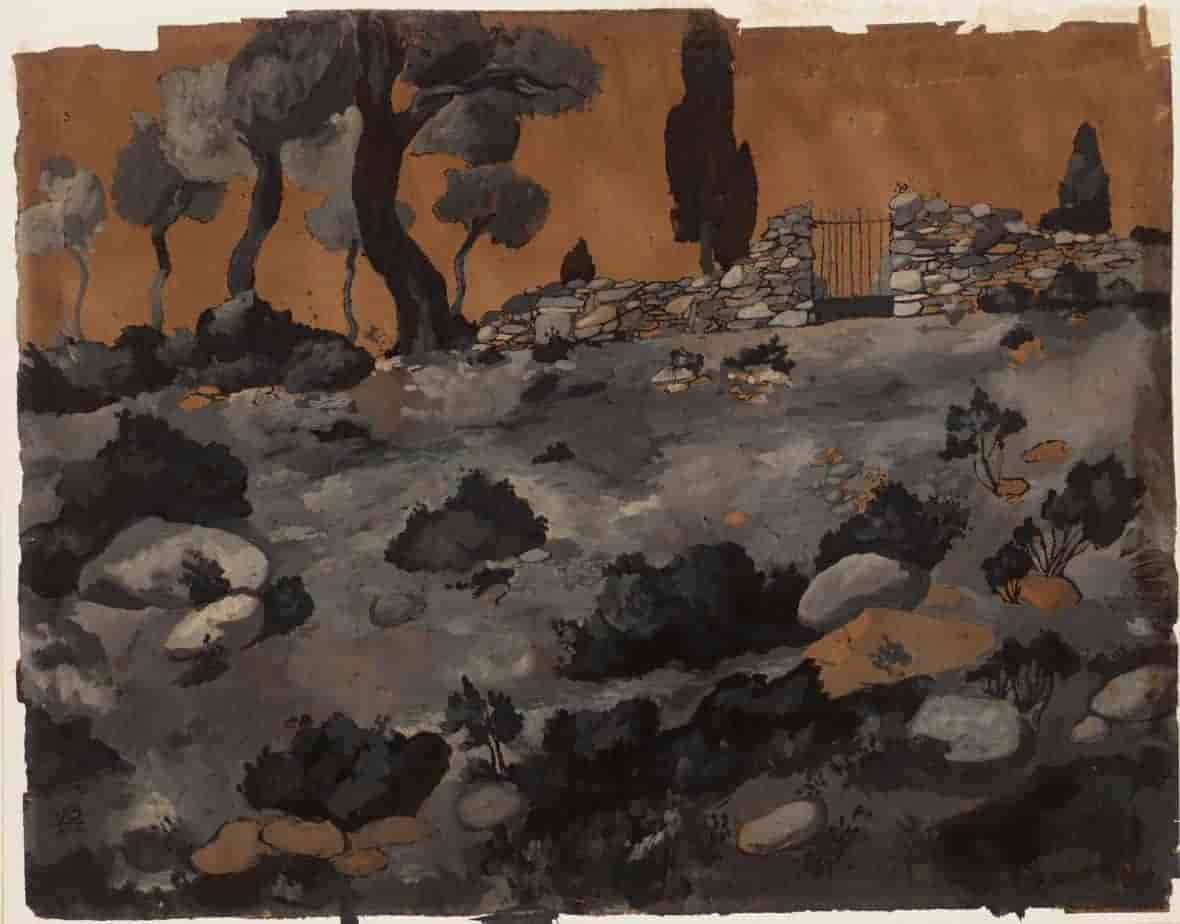

Header painting: Thomas Benjamin Kennington – Homeless