Aporia is a concept from philosophy but I’m talking about aporia when describing a literary (or rhetorical) device. Sometimes, but not always, aporia is used in everyday communications to dismiss, minimise and invisibilise someone else.

Think of it like a ‘conversational impasse’. A common scenario: Someone pretends to ask a question but they’re actually dismissing what you just said.

What you just said: I’m pretty sure I just experienced racism/sexism/queerphobia.

Aporia: Sure you’re not seeing that everywhere, even where it doesn’t exist?

[The statement behind the ‘question’: You’re oversensitive and imagining it.]

What you just said: I think I get worse menstrual cramps than other people.

Aporia: How would you even know what other people experience.

[The statement behind the question: Your pain doesn’t matter/Menstrual pain is necessary and expected.]

What you just said: I’m demisexual. For me that means I rarely experience sexual attraction.

Aporia: And I’m a special purple alien.

[The effect of the sarcasm is aporia: Demisexuality is something people make up to attract attention to themselves.]

For many reasons, it pays to know aporia when you hear it. People do it to each other all the time. You’ve probably experienced aporia yourself, and it doesn’t always come at you as sarcasm, or as a dismissive statement grammatically disguised as a so-called question.

Like all forms of abuse, aporia exists on a spectrum, from minor to major harm caused, and also on a different spectrum: of intent. Some speakers know they’re using it, others use it by accident. (Intent doesn’t equal effect.) Very few people could tell you it’s called ‘aporia’.

- Someone asks you a question which shows they’re not on your wavelength at all. They haven’t understood what you just said, and are re-routing the conversation to answer a different question entirely.

- Someone’s response shows they don’t take your own contribution seriously. They think you’ve misunderstood what’s really important, so they replace your actual question with something they consider to be more important.

- Maybe they haven’t listened to your contribution at all. Aporia can be a result of poor listening.

- Commonly, you’ve asked a literal question and get a rhetorical question for an answer. Or, you’ve asked a rhetorical question and get a literal answer.

Redirection with purpose is one thing, but masters of aporia need to be wary of using it to silence others, sometimes by accident.

Like other rhetorical devices, we don’t tend to name it ‘aporia’ unless it’s used with intent. When analysing texts, it’s good practice to assume storytellers do things for reasons (whether the storyteller was conscious of those reasons or not), so the term ‘aporia’ is useful when analysing interactions between characters, or between character and audience.

Why do writers make use of aporia?

- Writers like to use it in fiction because it makes for interesting ‘cross-talking’ in dialogue (a form of conflict), and also because fiction writers are always interested in power plays, especially when they’re kind of subtle.

- Aporia used to silence characters who are yet to discover their own power. They might be girl characters or other characters with intersecting marginalised identities. There’s a long tradition of speechlessness for women and marginalised identities in fiction. As Roberta Seelinger Trites puts it in her book Waking Sleeping Beauty: ’While experiencing the aphasia (speechlessness) of aporia, the individual cannot shape her own experience, nor can she interact with other people. She is only an object in other people’s dialogues.’

- Aporia is a good trick for characters in more powerful but fake mentor/ally roles. Someone who uses these techniques tends to come across as some kind of wise old sage (even when they’re no such thing). Fake versions of common archetypes are always interesting characters in fiction. (The fake ally or the fake opponent can be found in many excellent stories.)

Aporia To Show Humanity and Create Empathy

Matt Bird writes about a moment in the indie film Lady Bird in which a romantic opponent tries to use aporia on the character Lady Bird to shut her down, but she’s too savvy to fall for it and tells him to shut up.

(My own analysis of Lady Bird is here.)

Aporia To Show Character Arc

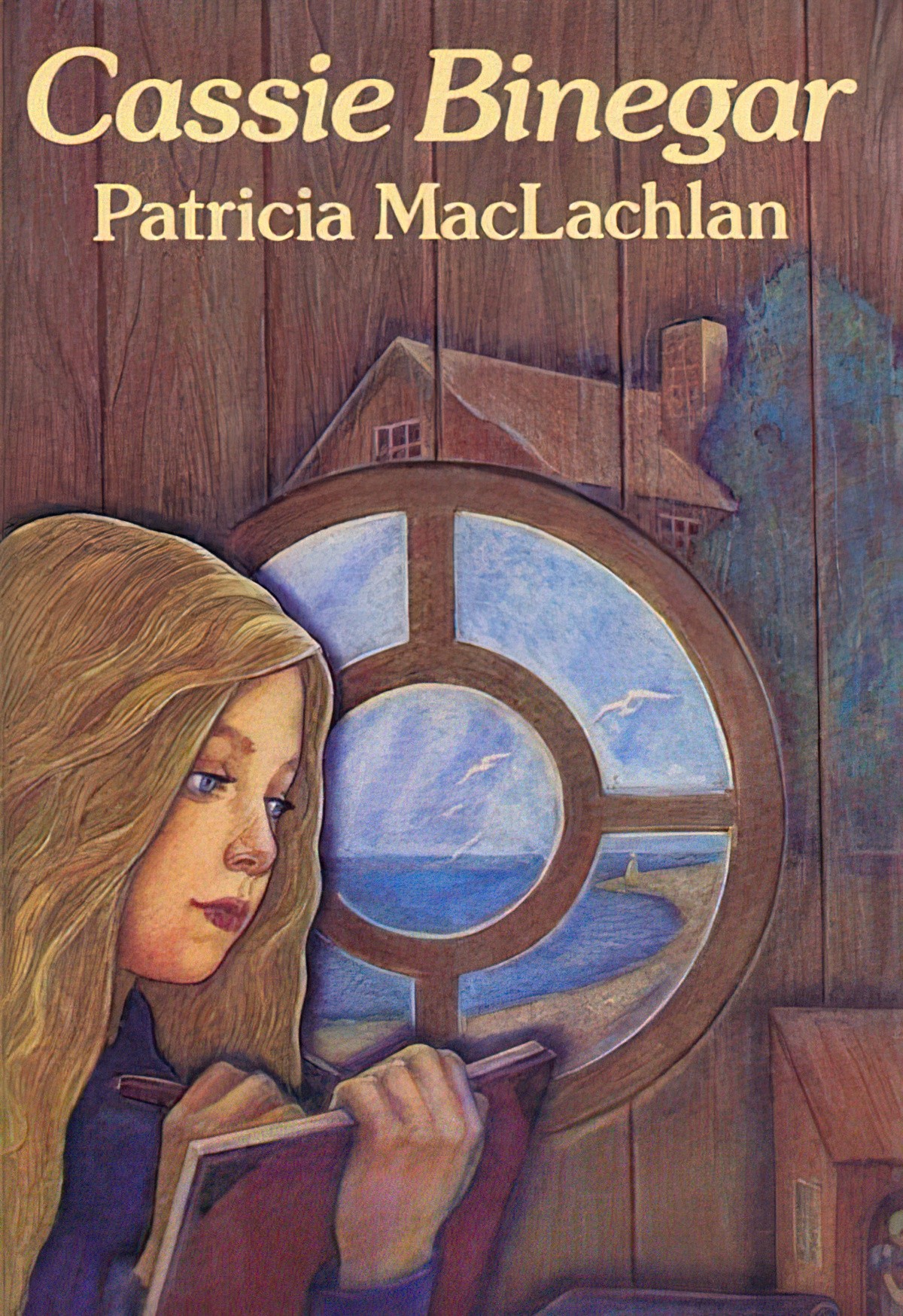

These examples come from Roberta Seelinger Trites in Waking Sleeping Beauty, who noticed the important role of aporia in building the confidence of an initially voiceless young adult character created by Patricia MacLachlan (who also wrote Sarah, Plain and Tall).

CASSIE BINEGAR

Cassie Binegar was published in 1980, when feminist talking points were newer to the mainstream culture, and therefore addressed more overtly in young adult literature.

Cassie: Says she wants her family to be “like everyone else”.

James [older brother]: “And what is everyone else like, Cass?” [rhetorical question]

Cassie: [can’t answer, retreats into self, tells brother he doesn’t understand]

Cassie: “Why don’t I have a space of my own [to write in]?” [a literal question]

Jason [an older writer]: “Each of us has a space of his own. We carry it around as close as skin, as private as our dreams. What makes you think you don’t have your own, too?” [rhetorical answer, denial of legitimacy of Cassie’s literal question]

Trites talks next about ‘semiological enigma’ as defined by Paul de Man, and the concept of an ‘aporia silence’:

Modifying the classical definition of the aporia to demonstrate how ambiguity influences textuality, de Man describes the tension that occurs when the answer to a rhetorical question negates the existence of the original question. An aporia silence invariably results from a rhetorical question when “It is impossible to decide by grammatical or other linguistic devices which of the two meanings (that can be entirely incompatible) prevails. Thus, to the rhetorical question of a male authority which is notably couched in diction that denies the legitimacy of her original question, Cassie has no answer. She reinforces the silence she feels by turning out the light, “leaving herself and the questions in the dark”.

Roberta Seelinger Trites

Patricia MacLaughlan continues to show readers how Cassie is silenced by various authority figures in her life, next time by her own grandmother.

Cassie: How come you don’t see things the way they are?” [literal question]

Grandmother: Tell me, just how are things? How are things? [rhetorical question, silencing Cassie]

Cassie: [thinks to herself ‘no answers anywhere’, bursts into tears]

Grandmother: [comforts Cassie]

Next, Trites explains how the grandmother tells a story to ‘reinforce the matrilineal bond between them’ and to teach her granddaughter to ‘develop more than one internal perspective for judging things’.

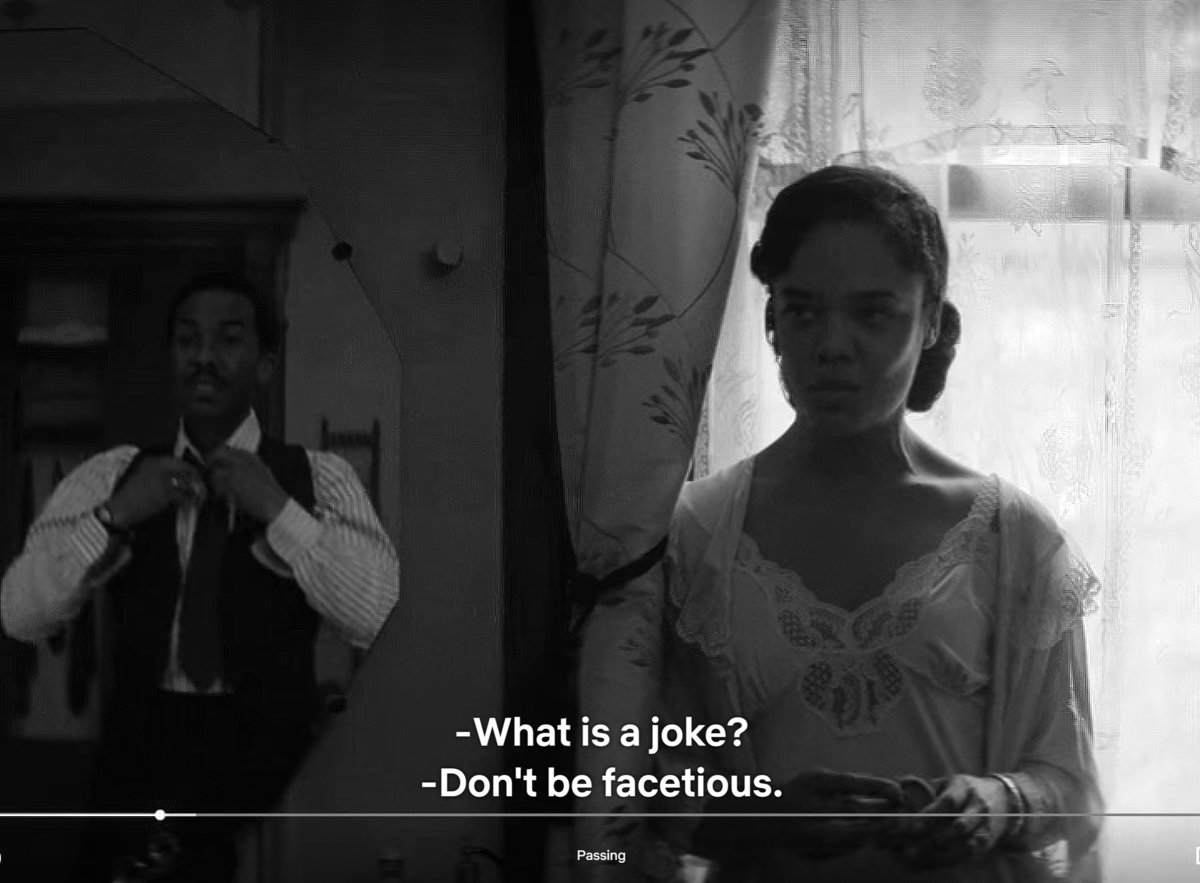

PASSING (2021)

Passing is a black-and-white film based on the same-named 1929 novel by Nella Larsen. The title refers to African-Americans who had skin colour light enough to be perceived as white.

In the scene below, Irene Redfield tries to talk to her doctor husband. She is expressing concern about their two boys, but the husband thinks he knows better. He shuts her down with aporia.

BRIAN: I wish you wouldn’t be ever fretting about those boys. They are fine. They’re perfectly good, strong, healthy boys.

IRENE: I suppose. I’m just afraid he’s picked up some queer ideas about things from some of the other boys.

BRIAN: “Queer?” What about?

IRENE: You know, things young boys be thinking about.

BRIAN: Ah. You mean about sex?

IRENE: Yes. Jokes. Things like that.

BRIAN: If sex isn’t a joke, what is it? What is a joke?

IRENE: Don’t be facetious.

The aporia male characters wield against their woman lovers is often quite specific in nature: It takes the form of flirtation. By ‘failing’ to perceive talk of sex as flirtation, Brian means Irene to look ridiculous because of her anxieties. He is the doctor; he knows best. He tells her they are ‘healthy’. End of. Rather than hear her specific concerns about their sons, he deflects entirely by asking a pseudo-philosophical question: “If sex isn’t a joke, what is it?” He goes even further: “What is a joke?”

When Irene fails to push back against her husband, despite calling him out as ‘facetious’ and thereby showing the audience she knows exactly what’s going on, this leaves plenty of room for her character arc: from quiet, passive observer to empowered.

A COMEDY EXAMPLE

Like almost anything, this device can be flipped and used for comedic effect. Take Episode 8, Season 4 of American TV sit-com, Young Sheldon.

Sheldon doesn’t want to get out of bed because everything just seems so futile now that he doesn’t even know what’s real anymore.

Recap

Until Sheldon is persuaded by his philosopher professor that it is exciting to wonder about philosophical questions (rather than overwhelming) every interaction he has with others is an example of aporia. This drives everyone around the bend.

Father: I don’t have time for this nonsense.

Sheldon: What is time? What is is?

Header illustration: From American Boy Magazine – May 1936 for a story called “A Question Of Method” The art is by Frank Schoonover.