I have previously written about utopias, snail under the leaf settings, idylls and dystopias. I thought I had -topias covered. Then I came across the word heterotopia. What’s that, now?

Foucault uses the term “heterotopia” to describe spaces that have more layers of meaning or relationships to other places than immediately meet the eye. In general, a heterotopia is a physical representation or approximation of a utopia, or a parallel space (such as a prison) that contains undesirable bodies to make a real utopian space possible.

thanks, Wikipedia.

That last clause makes zero sense to me. The article gets more impenetrable from there.

DOES EVERYONE FEEL LIKE THEY’RE IN A HETEROTOPIA?

After taking a close look at what the concept means, I’m reminded of when I was teaching. Teachers would refer to ‘the real world’ as if it were somewhere else. In ‘the real world’ people don’t get 12 weeks of holiday. In ‘the real world’ you don’t get a fixed but safe salary every two weeks. Like some sort of wild creature taking risks real world people have to run their own businesses or something.

But then I had a job with public service. I noticed that people who work for the public service also talk about everyone else is if everyone else is ‘the real world’. Council workers do it, too. I now realise that teaching, like few other jobs, really is ‘the real world’. In a school you’re dealing with whatever (delight and) trouble comes through the door — family issues, medical issues, car crashes, rape, imprisonment and physical assault on top of the day-to-day actual teaching and paperwork.

This feeling that everyone else is ‘the real world’ and you yourself are living in some sort of insulated bubble is quite widespread, and I wonder if any group of professionals do in fact consider themselves The Real World. I suspect even emergency department nurses are prone to this feeling, working at night when everyone else is perceived to be asleep, and on the side of the bed where you are expected to be calm and helpful rather than show your human side.

BRIEF AND SIMPLE DEFINITION OF HETEROTOPIA

Other spaces. These spaces are both real and unreal.

Other people have said similar things about social groups, their spaces and hierarchies of power:

As Peter Berger and Thomas Luckman describe … institutions delineate a symbolic area which they call reality, and define and regulate relations and actions within that area. Knowledge generated within this area ‘is socially objectivated as knowledge, that is, as a body of generally valid truths about reality.’ Thus any alien — deviant — kind of knowledge is seen as a ‘departure from reality,’ or as ‘moral depravity, mental disease, or just plain ignorance.’ But groups may share a deviant version of the symbolic universe, and elevate it into ‘a reality in its own right,’ thereby challenging the claim of reality made by the orthodox group. Berger and Luckman conclude that ‘such heretical groups posit not only a theoretical threat to the symbolic universe but a practical one to the institutional order,’ and invariably lead to repressive or suppressive procedures’.

Marilyn French in Beyond Morals: Women, Men & Power, summarising part of a 1967 paper called “The social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge”.

FOUCAULT’S 6 PRINCIPLES OF HETEROTOPIA

PRINCIPLE ONE

The heterotopia is both real and unreal.

Foucault uses the example of a mirror. The object of a mirror exists, but the reflection in the mirror does not. In this way, the mirror is both real and unreal.

Heterotopies are constructed. They exist in all cultures in some ways, though each culture may have different types.

PRINCIPLE TWO

A heterotopia has a specific operation anchored to a specific time.

Take the example of cemeteries. Before the 18th century, cemeteries were next to churches. Only important individuals were allowed to be buried there. Lower classes were taken to charnel houses.

But near the end of the 19th century, cemeteries started to be developed on the outskirts of town.

Cemeteries were not heterotopies but then they became so.

Why the change?

Foucault tracks this in tandem with the rise of the (medical) clinic. Foucault considered these new cemeteries on the outskirts of town heterotopies because people don’t want to see dead bodies. Dead bodies remind us of our own mortality.

How does this track with the rise of medicine? People started to expect medicine to prevent death, and to prevent it altogether. Medicine allowed us to pretend, for the first time, that death wasn’t happening all around us, all the time.

PRINCIPLE THREE

Heterotopies have incompatible elements in a single state.

The classic example of this principle of heterotopia is a garden. Gardens contain vegetation from far and wide in the same space (regionally and globally). The act of gardening is an act of organisation. Your favourite flowers/bushes go in a favoured spot. This leads to incompatible elements but a sense of trying to establish order.

PRINCIPLE FOUR

These elements function in temporal discontinuity.

In simple English: There’s a break in normal time flow. Museums and libraries are a good example of this because these spaces bring past, present and future together in the same space. But they are also frozen in time, protected from its ravages.

PRINCIPLE FIVE

Heterotopies are demarcated but acceptable. They are linked to the opening and closing of doors.

There must be some way to enter and exit. There must be either compulsory entrance (a prison) or have some rite or ritual before admittance. In a cemetery, the ‘rite’ is simply ‘being dead’.

PRINCIPLE SIX

Heterotopies operate in relation to all of those spaces.

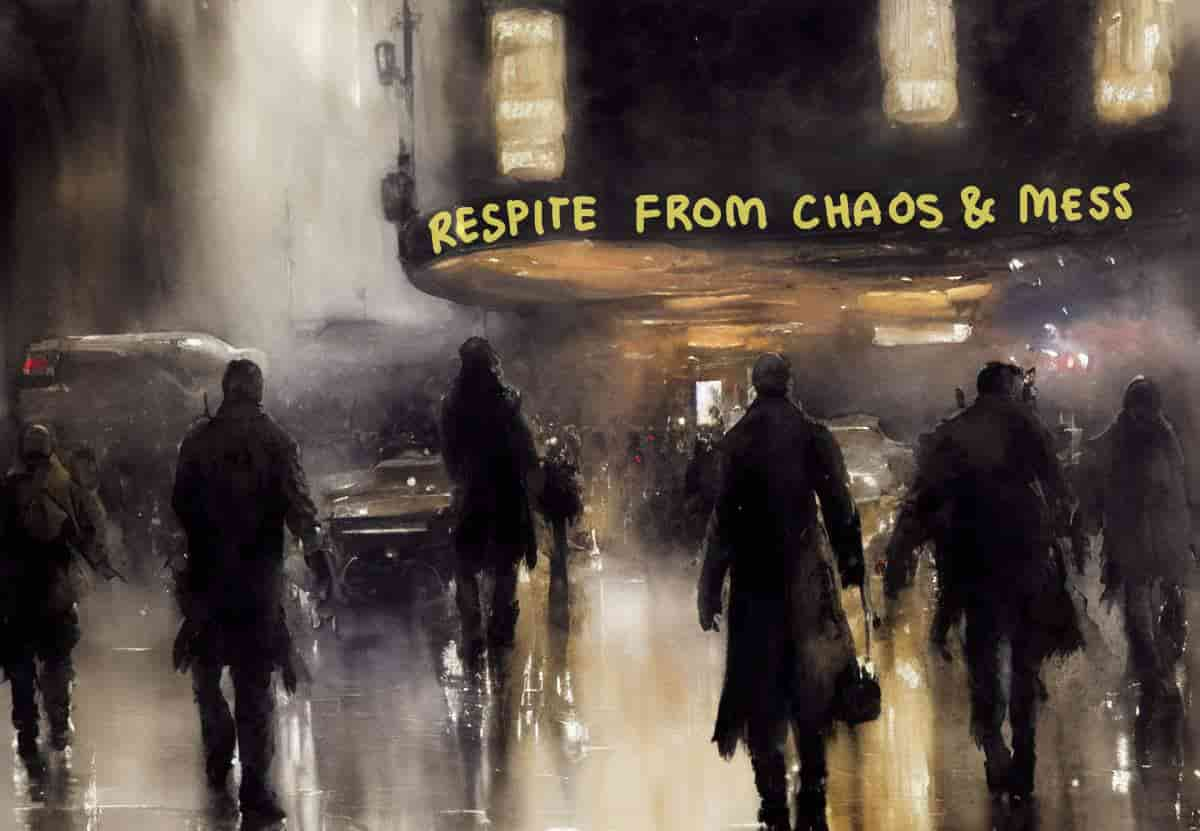

Foucault considers heterotopies as spaces which create some kind of illusion. A good example is a brothel. Brothels allow interior fantasies to play out but these are separate from the domestic space.

The space of compensation is also a kind of heterotopia. These places exist to counter our real but messy world.

Heterotopies tend toward two extremes: Rare chaos or rare order.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE WORD HETEROTOPIA

Heterotopia is based on the concept of utopia.

- The Greek ‘u’ bit at the beginning of utopia means ‘not’.

- The ‘topia’ part means ‘place’.

So if utopia means a place that is not — a place which doesn’t actually exist — heterotopia means a place that is different. The word ‘utopia’ has been around since 1516 thanks to Thomas More.

The word ‘utopia’ is a bit confusing, actually, because it was based on a Greek pun. Of course, the pun got totally lost in translation. So in Thomas More’s pun, utopia meant both ‘place that is not’ and ‘good place’. (ou-topos vs. eu-topos). In modern everyday English, when we say ‘utopia’ we’re generally referring to the good place.

Heterotopies differ from these ‘good’ utopias because they allow for the inherently unpredictable nature of human contexts to disrupt this space.

The word heterotopia has only been around since 1967, thanks to Michel Foucault, who was giving a lecture to students of architecture at the time.

The sorry truth is, Foucault made this word up, explained it a bit, and then left it alone. He’s pretty inconsistent in what he says. He starts off talking about bodies in spaces, then talks about documents (in libraries and museums.) Maybe he confused his own self as he was explaining it. BUT he said just enough to make a lot of us want to know more, and others have said a lot since. He may have been having fun, messing around with a half-formed idea.

But numerous people picked up the word and ran with it. The concept of the heterotopia is now well-known in architecture, urban planning, literary studies and in pretty much any field where people are thinking about how space is used.

HETEROTOPIA AND POWER

Constructed spaces have their own power. Spaces are constructed to be powerful. Perhaps the biggest contribution Foucault left as his legacy: He asked us all to think about the dynamics of power. It’s always worth taking a close look at spaces, how they are used, and who is allowed entry.

Who decides what utopia looks like, anyway? The designation of heterotopia is contingent on a shared ideal space.

There remains plenty of space to develop the idea of Foucault’s heterotopia in the fields of, say, colonial studies, queer studies and disability studies.

WHY WAS HETEROTOPIA INVENTED IN THE 20TH CENTURY?

Heterotopia is a 20th century concept because it best describes 20th century life and beyond.

In the Middle Ages there was a hierarchic ensemble of places when it came to humans here on Earth:

- sacred places and profane places

- protected places and open, exposed places

- urban places and rural places.

In cosmological theory, there were:

- the super-celestial places (as opposed to the celestial)

- the celestial place was in its turn opposed to the terrestrial place.

(Galileo put an end to that. Galileo’s new theories made people realise the universe was way bigger than they’d thought. They also separated ‘time’ from ‘the sacred’, but that separation still hasn’t happened entirely with the concept of ‘space’.)

HETEROTOPIA SUMMARISED

If that previous explanation made no sense, try this:

- Heterotopia is a ‘real world utopia’. A utopia has no real place. A utopia is a ‘perfect version’ of a real place — a society turned upside down.

- The mirror is a kind of utopia. (It is a placeless place.) The mirror is also a kind of heterotopia as well as a utopia. The mirror does exist in the reality of your bathroom. But while the person you see in the mirror is real, the image in the mirror is unreal. The mirror is the ultimate link between the real and the unreal. That’s why mirrors are so fictionally interesting.

- A heterotopia, similar to a utopia, is a kind of ‘unreal’ space.

- Time works differently in a heterotopia.

- Heterotopies have a system of opening and closing that both isolates them and makes them penetrable. In general, the heterotopic site is not freely accessible like a public place. Either the entry is compulsory, as in the case of entering a barracks or a prison, or else the individual has to submit to rites and purifications.

- A heterotopia is a place that represents society, but in a distorted way which calls to mind particular idealised aspects of the culture.

- Heterotopies attempt to encourage transition from a space of chaotic governance and leadership to a mapped, organised one.

- Every culture has the concept of a heterotopia: privileged, sacred and forbidden places reserved for certain people.

THE TWO MAIN TYPES OF HETEROTOPIES

Crisis HeterotopiES

(Crisis simply means ‘turning point in someone’s life’ e.g. puberty. Boarding schools and honeymoon suites exist to house those going through a so-called crisis. (Seriously, a better translation for this is ‘turning point’).

This is where you find adolescents, menstruating women (See Menstruation In Fiction), pregnant women, women in general, the elderly. We have fewer of these ‘crisis heterotopies’ in modern society. It’s considered not-nice to lock people away when we don’t want to deal with them.

We still have boarding schools and many countries have the military service for young people.

Heterotopies of deviation

These are spaces for people who contradict social norms. Prisons, hospitals, cemeteries. We don’t want to see these people, but we need to know where they are. So we put them in spaces parallel to our world, which we try to make as utopian as possible.

EXAMPLES OF HETEROTOPIES

Let’s look at the concept of heterotopia from a perspective I can sink my teeth into — children’s literature and pop culture.

Boarding Schools

Hogwarts is a well-known example. (The author is a transphobic bigot; on the topic of transphobia, always listen to trans people.)

Harry Potter’s boarding school is a heterotopia because it is both separate from but also intimately connected to the world beyond its walls. Zooming in on more specific spaces within the Harry Potter universe we have some even better examples of heterotopies:

- 12 Grimmauld Place, the ancestral home of the Black family, located in the Borough of Islington, London, in a Muggle neighbourhood

- The tent that Harry, Ron and Hermione share in book seven

- The Room of Requirement is a space within the place of the school proper. It only appears when a person is in great need of it. The room is thought to have some degree of sentience, because it transforms itself into whatever the witch or wizard needs it to be at that moment in time, although there are some limitations. For example, it cannot create food, as that is one of the five Principal Exceptions to Gamp’s Law of Elemental Transfiguration. It is believed that the room is Unplottable, as it does not appear on the Marauder’s Map, nor do its occupants, although this could simply be because James Potter, Remus Lupin, Sirius Black, and Peter Pettigrew never found the room.

Those two spaces exist in the margins of safety and danger. There are shifts from order to disorder, from safety to danger. Young adults can be powerful when it comes to opposing the abuses that permeate the spaces in our own world. What the trio does in Hogwarts does not stay in Hogwarts. The teenagers go against authority, learning the limits of their own power. For this they need to operate in a fictional space which is part fantasy, part real-world.

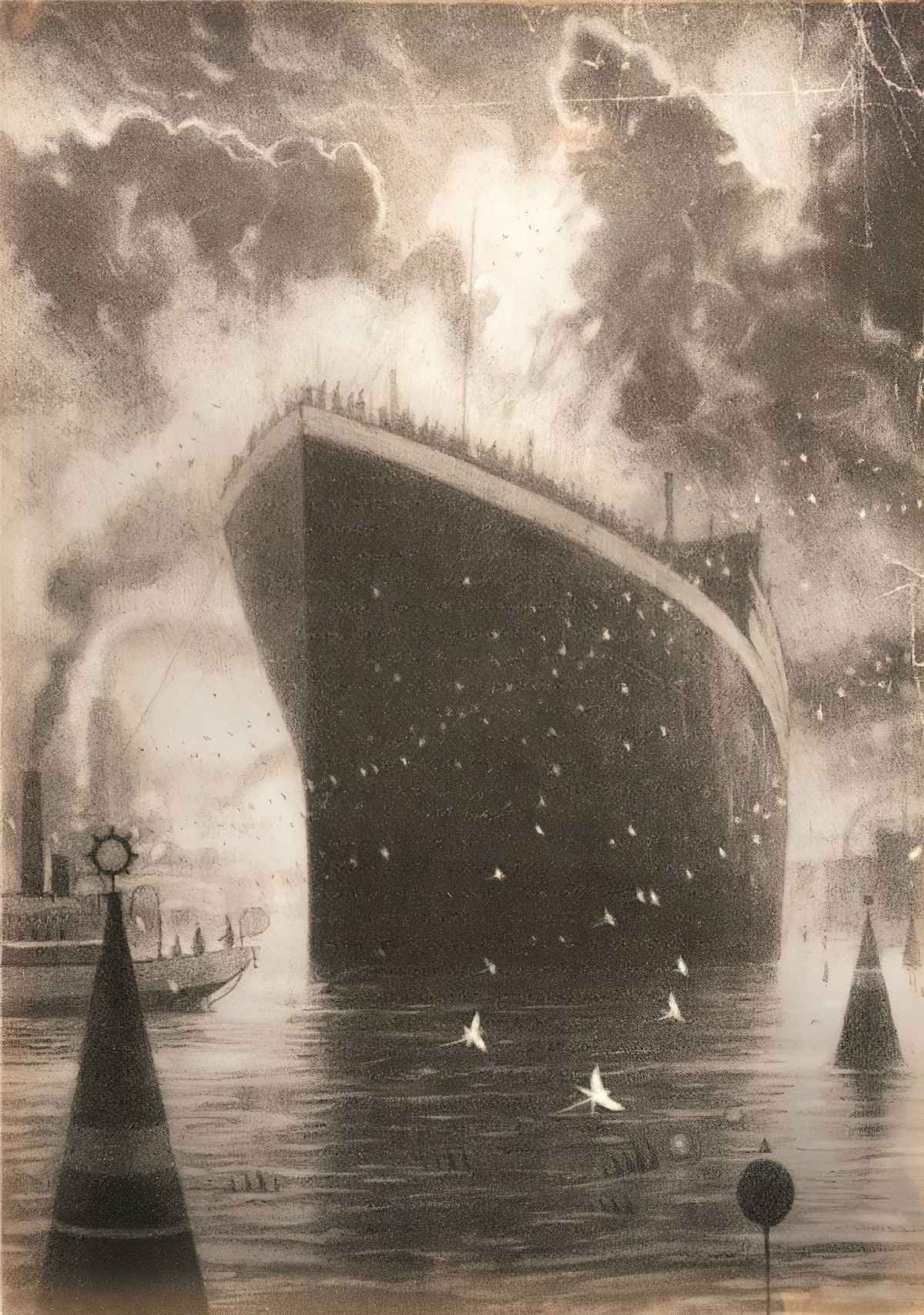

Train And Steamships

Many children’s stories still feature steam trains even though most modern kids have never ridden one in their lives. The steam train, or the ship (offered as an example by Foucault himself) are especially good as heterotopies because they operate like alternative worlds. They are kind of like a portal in a portal fantasy, One obvious reason to linger in a portal is to give an audience the enjoyment of being transported to another world. Another reason is to make sure the audience doesn’t zone out for a moment and lose track of where they are. But there are other reasons.

See also: The Symbolism of Trains

When the fantasy portal is something like a train or a ship, this gives the writer space and time to:

- Establish the logic of this new universe

- To subvert it

- To have it clash with the logic of the existing, real world universe.

(In the real world, the ship which inspired the film Pirate Radio (2009) existed in a kind of heterotopia, able to broadcast non-classical music due to floating outside the reach of the rule makers.)

Anne With An E, the Netflix miniseries based on Anne of Green Gables, also features a steamship during the episode when Anne is sent away from Prince Edward Island.

The boat is a floating piece of space, a place without a place, that exists by itself, that is closed in on itself and at the same time is given over to the infinity of the sea and that, from port to port, from tack to tack, from brothel to brothel, it goes as far as the colonies in search of the most precious treasures they conceal in their gardens, you will understand why the boat has not only been for our civilization, from the sixteenth century until the present, the great instrument of economic development… but has been simultaneously the greatest reserve of the imagination. The ship is the heterotopia par excellence. In civilizations without boats, dreams dry up, espionage takes the place of adventure, and the police take the place of pirates.

Foucault

Pirate stories set on ships are likewise heterotopic.

Honeymoon Destinations

In the past the ‘honeymoon trip’ had the purpose of removing a young woman from society so that she could lose her virginity elsewhere (out of sight, out of mind — because everyone’s always been scared of young female sexuality). So the honeymoon destination is a kind of heterotopia, without geographical markers. The wedding is public but the honeymoon consists of acts we probably don’t want to see.

The honeymoon destination is the closest real world analogue I can think of for the portal fantasy that takes a character (and her sidekick) away to a fun and fabulous land where children can eat as much as they like of whatever they like and get up to other carnivalesque mischief. After all, in children’s literature food is basically sex.

Libraries and Museums

Libraries and museums are a 20th century heterotopia. Time works differently here because in these places time never stops ‘building up and topping its own summit’.

A lot of children’s books feature libraries — probably because children’s authors are huge fans of books. For instance, A Series of Unfortunate Events contains memorable libraries.

Cinemas and Theatres

Juxtaposition is very important when it comes to the importance of a heterotopia. Cinemas and theatres are heterotopic because they are capable of juxtaposing “in a single real place several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible”. There’s the audience, sitting comfortably in their chairs, juxtaposed with whatever mayhem’s going on on the screen or stage.

These are sites of temporary relaxation.

The theatre brings onto the rectangle of the stage, one after the other, a whole series of places that are foreign to one another; thus it is that the cinema is a very odd rectangular room, at the end of which, on a two-dimensional screen, one sees the projection of a three-dimensional space.

Foucault

Drag queen cabarets are especially good examples of heterotopies because the men dressed as ‘women’ are not mimicking real women at all, but a particular kind of ideal woman, with exaggeratedly femme-coded attributes. What is the raison d’etre of kikis and drag queen cabarets? Drag queens highlight the ways in which femininity is a performance. The same performance decoded through a misogynistic lens: by highlighting that femininity is a performance, women are seen to be performative, duplicitous and basically liars when we put on ‘masks‘ such as make-up, and dress to make our legs look longer and so on.

In children’s books there are few (if any) drag queen cabarets — this is considered adult entertainment. But we do often get a form of “cross-dressing”. This is most often done to disempower boys by comparing them to girls, long considered a lesser gender. This is not a form of heterotopia but a kind of gag. There is a drag performance in the movie version of Coraline — not a gender transgressive one but one performed by the two women who live together next door. (Are Miriam Forcible and April Spink cis women? I like to think they are not.)

Whenever a character in a story visits the cinema or the theatre and watches fiction on the stage, this might (or might not) be metafictional, depending on whether the author calls attention to the fact that, Hey, look, this character is watching a play and you’re reading a book about them watching a play.

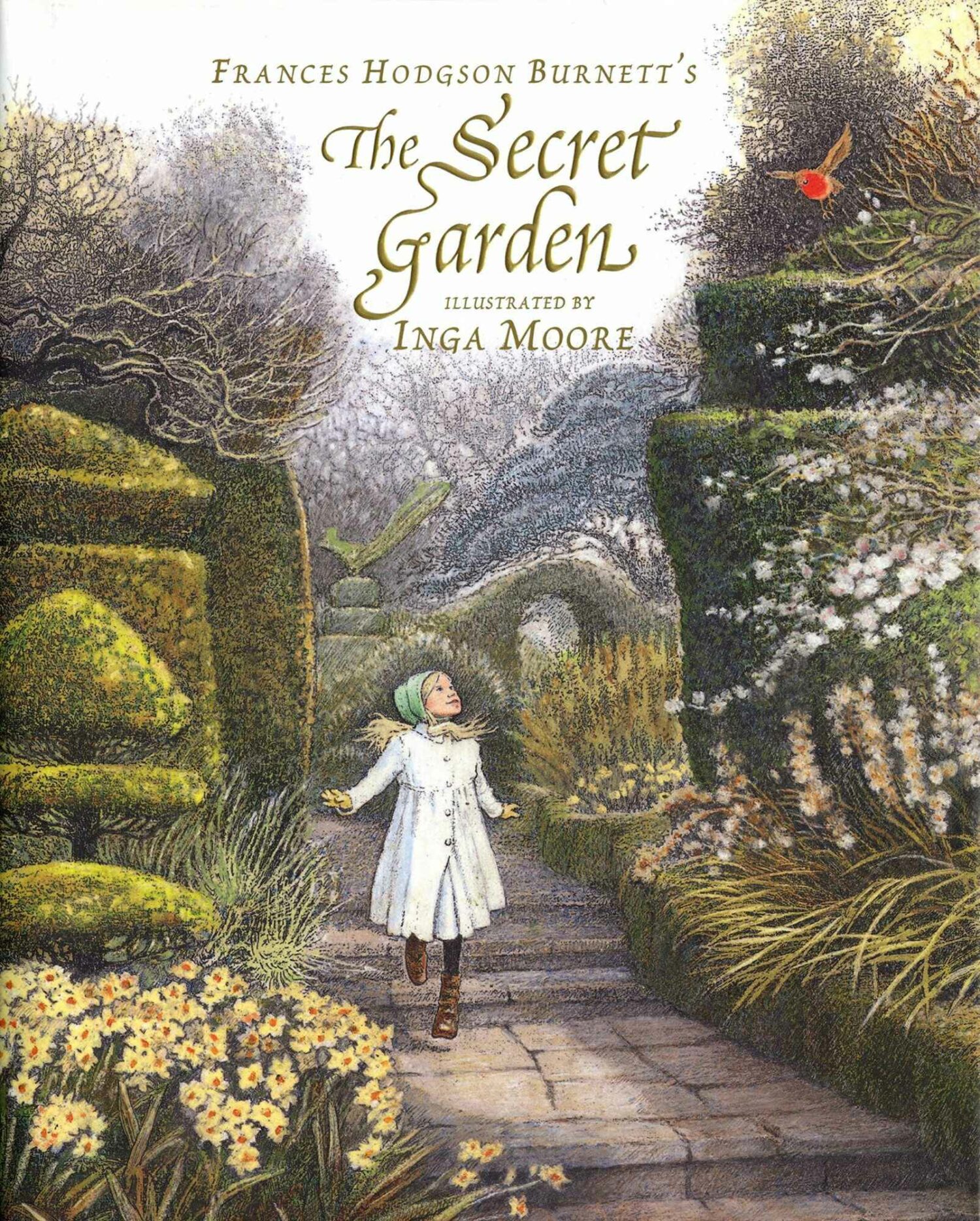

Gardens

Perhaps the oldest example of these heterotopies that take the form of contradictory sites is the garden. We must not forget that in the Orient the garden, an astonishing creation that is now a thousand years old, had very deep and seemingly superimposed meanings. The traditional garden of the Persians was a sacred space that was supposed to bring together inside its rectangle four parts representing the four parts of the world, with a space still more sacred than the others that were like an umbilicus, the navel of the world at its center (the basin and water fountain were there); and all the vegetation of the garden was supposed to come together in this space, in this sort of microcosm. As for carpets, they were originally reproductions of gardens (the garden is a rug onto which the whole world comes to enact its symbolic perfection, and the rug is a sort of garden that can move across space). The garden is the smallest parcel of the world and then it is the totality of the world. The garden has been a sort of happy, universalizing heterotopia since the beginnings of antiquity (our modern zoological gardens spring from that source).

Foucault

Since heterotopies represent a society’s idealised version of reality, each culture has its own raison d’etre. Japanese gardens are all about balance, because balance is important to Japanese people. French gardens are made of straight lines whereas English gardens mimic the irregularity of nature (with the emphasis on ‘mimic’). Gardens are attempts to recreate an ideal, utopian nature.

Heterotopia is also about the side-by-side, the near and far, and simultaneity.

Botanical gardens in particular are driven by the desire to reconstitute the whole world in a walled enclosure.

The golf club is a kind of massive, over-manicured garden — another example of heterotopia. Malcolm Gladwell did an excellent podcast on American golf clubs, and how taxpayers are all paying for them even though they are accessible by very few.

Cemeteries

A cemetery is a heterotopia because the tombs form a sort of ideal town for the deceased, each placed and displayed according to social rank. Our local graveyard divides people according to religion — we have protestants on one side, Catholics on the other. The odd atheist (I assume) is over by the fence, as far as possible away from the religious folk. This represents some sort of idealised town, in which people of different/no faiths don’t have to deal with each other.

Also, a cemetery gives the illusion to its visitors that their departed relatives still have an existence and status, symbolised by the stone of their tomb. This is a simulated utopia of life after death, but it is also a representation of the real world, where things like your religion and status — as described briefly on your tombstone — actually matter.

Take the strange heterotopia of the cemetery. The cemetery is certainly a place unlike ordinary cultural spaces. It is a space that is however connected with all the sites of the city, state or society or village, etc., since each individual, each family has relatives in the cemetery. In western culture the cemetery has practically always existed. But it has undergone important changes. Until the end of the eighteenth century, the cemetery was placed at the heart of the city, next to the church. In it there was a hierarchy of possible tombs. There was the charnel house in which bodies lost the last traces of individuality, there were a few individual tombs and then there were the tombs inside the church. These latter tombs were themselves of two types, either simply tombstones with an inscription, or mausoleums with statues. This cemetery housed inside the sacred space of the church has taken on a quite different cast in modern civilizations, and curiously, it is in a time when civilization has become ‘atheistic,’ as one says very crudely, that western culture has established what is termed the cult of the dead.

Basically it was quite natural that, in a time of real belief in the resurrection of bodies and the immortality of the soul, overriding importance was not accorded to the body’s remains. On the contrary, from the moment when people are no longer sure that they have a soul or that the body will regain life, it is perhaps necessary to give much more attention to the dead body, which is ultimately the only trace of our existence in the world and in language. In any case, it is from the beginning of the nineteenth century that everyone has a right to her or his own little box for her or his own little personal decay, but on the other hand, it is only from that start of the nineteenth century that cemeteries began to be located at the outside border of cities. In correlation with the individualization of death and the bourgeois appropriation of the cemetery, there arises an obsession with death as an ‘illness.’ The dead, it is supposed, bring illnesses to the living, and it is the presence and proximity of the dead right beside the houses, next to the church, almost in the middle of the street, it is this proximity that propagates death itself. This major theme of illness spread by the contagion in the cemeteries persisted until the end of the eighteenth century, until, during the nineteenth century, the shift of cemeteries toward the suburbs was initiated. The cemeteries then came to constitute, no longer the sacred and immortal heart of the city, but the other city, where each family possesses its dark resting place.

Foucault

Cemeteries are a good example of how time is different in a heterotopia. In a cemetery humans have met with broken time — starting at the time of death.

See: The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman

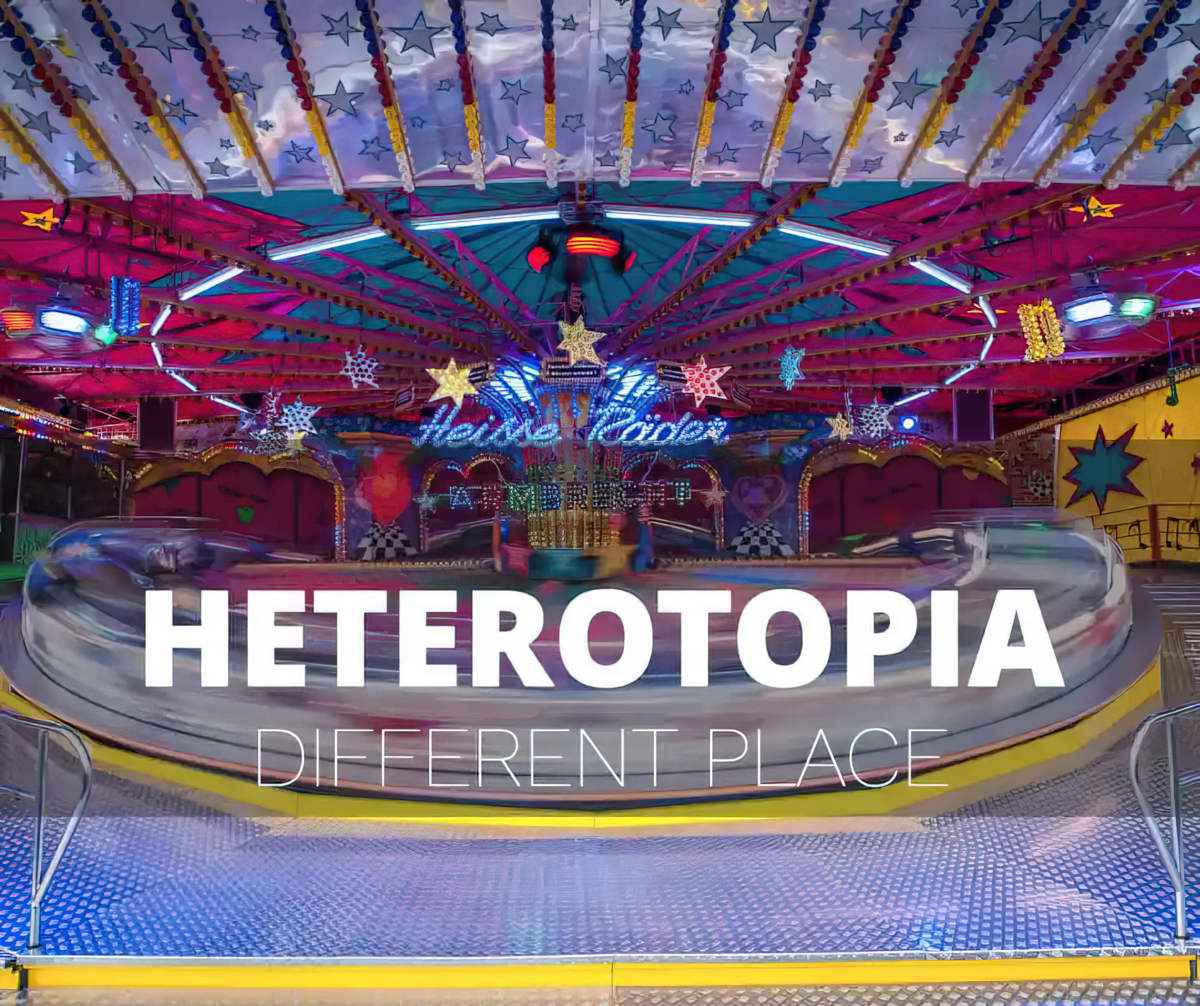

Fairgrounds

[Fairgrounds are] marvelous empty sites on the outskirts of cities that teem once or twice a year with stands, displays, heteroclite objects, wrestlers, snakewomen, fortune-tellers, and so forth.

Foucault

The field turns into a fairground for maybe one week per year. In this way, the fairground disrupts temporal continuity. It comes back year after year, so if we visit that fair in any given year, we may later conflate memories. (When did you drop your candyfloss in the mud puddle? Was it two years ago, or five?) The precarity of the fairground is part of the enjoyment. If it were there all year, it wouldn’t feel so special.

Disney World is a permanent fixture, but is the ultimate real world heterotopia. The characters are really nice to visitors not because Donald Duck is best friends with every visitor but because friendliness and photo opportunities are the service parents have paid for. The place is open only to those with enough money to enter — poverty and beggars are absent. The ‘city’ itself is a miniaturised version of an idealised world. For more on Disney World as the ultimate heterotopia see this article.

Queer People Love Disney Parks. They Don’t Always Love Them Back from them.

Malls

Although this describes Disney World it applies equally to malls:

Stephen Fjellman explains in Vinyl Leaves that the ‘magic’ of Disney World is actually a cognitive overload associated with decontextualization. ‘Cognitive overload’ simply means that the visitors’ senses are constantly overloaded by stimuli: music, stories, animatronics, cute characters, pretty buildings, rides, simulations and more. The visitor is overwhelmed and loses part of his capacity to discriminate information or think.

Philosophy Now

In our local mall we have:

- Booths in the middle of the ‘street’ with salespeople trying to sell you mobile phone plans, insurance and do your taxes, depending on the time of year

- The sub-heterotopia of a children’s entertainment arena, again different depending on the time of year. Before Christmas you can pay for the simulated intimacy of a photo with Santa. During school holidays you can be tied up to bungee ropes and jump and flip up as high as the third level of the mall. For younger kids we have mechanical horses which ‘run’ if you rock them the right way.

- Music which is different depending on the store

- Smells — some unintended, like the chemicals coming out of the nail salon; others intentional, such as the smell of baking coming out of the gourmet bakery.

- Lighting which highlights some features over others

- Massive advertisements, often of semi-naked women, always young and either smiling or seductive.

- A help desk which supposedly caters to your every need, including telling you where to find things and dealing with misplaced items, like a patient mother

- Tiny cars with flags on the top, so toddlers can imagine the mall is a city

- Balloons with ‘Westfield’ written on them, simulating a party atmosphere

- Mechanical animals, which take you to an imaginary other world if you put two dollars in the slot.

While malls are the ultimate shopping heterotopia, individual shops do their best to emulate the exclusivity of their stores — the very definition of ‘brand’.

BALLPARKS

Related to malls are ballparks, a similarity which Michael T. Friedman underscores by using the word ‘mallparks’.

In Mallparks: Baseball Stadiums and the Culture of Consumption (Cornell UP, 2023), Michael T. Friedman observes that as cathedrals represented power relations in medieval towns and skyscrapers epitomized those within industrial cities, sports stadiums exemplify urban American consumption at the turn of the twenty-first century. Grounded in Henri Lefebvre and George Ritzer’s spatial theories in their analyses of consumption spaces, Mallparks examines how the designers of this generation of baseball stadiums follow the principles of theme park and shopping mall design to create highly effective and efficient consumption sites.

In his exploration of these contemporary cathedrals of sport and consumption, Friedman discusses the history of stadium design, the amenities and aesthetics of stadium spaces, and the intentions and conceptions of architects, team officials, and civic leaders. He grounds his analysis in case studies of Oriole Park at Camden Yards in Baltimore; Fenway Park in Boston; Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles; Nationals Park in Washington, DC; Target Field in Minneapolis; and Truist Park in Atlanta.

podcast description at the New Books Network.

In these spaces, especially the theme park, we go to these places to escape from our everyday, the quotidian parts of life where we work from nine to five, where we raise children or interact with people and it’s kind of that normal experience. But then we have these other experiences, we seek out things that elevate us and take us out of the normal day-to-day. We go to a baseball stadium and first off there’s the communion with tens of thousands of other people. There are very few spaces in American life where we are parts of large, physical crowds. So much of our lives are about being one on one or in small groups with people, or mediated through the television or Internet. It’s really a one-way unidirectional experience. But in a baseball stadium…you are surrounded by tens of thousands of people. You’re cheering as they’re cheering at the ups and downs, sharing the excitement of the moment, the disappointment of losing, the exhilaration of winning. In the span of a two and a half hour baseball game you go through the ups and downs of anticipating your team doing well or dreading falling behind.

And then there’s that one aspect, a horizontal engagement you’re having with these thousands of people, but you’re tied historically (vertically?) to a much deeper history, a much deeper set of experiences that go back decades, generations, even a century. At a family park in Boston you can literally sit in the same physical seat where your grandparents sat 85 years ago to cheer on the Red Sox. So not only are you in the moment surrounded by thousands of people, you are part of this history extending back. […] It’s that connection with the past that makes sport unique and special.

Michael T. Friedman, “Mallparks: Baseball Stadiums and the Culture of Consumption” (Cornell UP, 2023), speaking at the New Books Network.

NIGHTCLUBS

NOCTURNAL ADMISSIONS

In Nocturnal Admissions: Behind the Scenes at Tunnel, Limelight, Avalon, and Other Legendary Nightclubs (Santa Monica Press, 2022), nightclub director Steve Adelman reflects on his years working in some of the world’s most popular nightclubs. In his memoir, Adelman reflects on his work in in New York City in the nightclub heyday of the late 1980s and 1990s, at the Roxy, Limelight, Tunnel, and Palladium, followed by Avalon (Boston, Hollywood, and Singapore locations), and the New Daisy Theatre in Memphis. Nocturnal Admissions is a timely, nonconventional look at one of pop culture’s most outwardly glamorous, yet misunderstood industries, bringing the reader backstage into the world of nightlife at its highest level.

Wearing the multiple hats of ringmaster, entrepreneur, guidance counselor, multimillion-dollar dealmaker, and music soothsayer, Adelman chronicles an improbable journey from small town to big city, filled with a cast of characters he could never have imagined: People named Hedda Lettuce, Jenetalia, Maxi Min, Jiggy, who collide with and around the likes of Jack Nicholson, Bruce Willis, Sir Richard Branson, Leonardo DiCaprio, RuPaul, Rudy Giuliani, and Snoop Dogg, among many, many others.

Navigating city crackdowns, crazed partners, and cultural differences, Adelman relates how he watched his Nana out-dance an ex-NFL lineman, was chastised by Bob Dylan, launched the EDM musical movement, helped created the “mash up” with Perry Farrell, butted heads with Jerry Falwell, rang in the New Year with Matt Damon’s mother, leveraged porn star Jenna Jameson, relied on advice from felons, almost pancaked Prince, and built the world’s most lavish nightclub. Nocturnal Admissions is a hilarious, adrenaline-filled ride through the peak decades of the world’s most famous nightclubs and nightlife scenes.

New Books Network

QUEER NIGHTLIFE

The mass shooting at a queer Latin Night in Orlando in July 2016 sparked a public conversation about access to pleasure and selfhood within conditions of colonization, violence, and negation. Queer Nightlife (U Michigan Press, 2021) joins this conversation by centering queer and trans people of color who apprehend the risky medium of the night to explore, know, and stage their bodies, genders, and sexualities in the face of systemic and social negation. The book focuses on house parties, nightclubs, and bars that offer improvisatory conditions and possibilities for “stranger intimacies,” and that privilege music, dance, and sexual/gender expressions. Queer Nightlife extends the breadth of research on “everynight life” through twenty-five essays and interviews by leading scholars and artists. The book’s four sections move temporally from preparing for the night (how do DJs source their sounds, what does it take to travel there, who promotes nightlife, what do people wear?); to the socialities of nightclubs (how are social dance practices introduced and taught, how is the price for sex negotiated, what styles do people adopt to feel and present as desirable?); to the staging and spectacle of the night (how do drag artists confound and celebrate gender, how are spaces designed to create the sensation of spectacularity, whose bodies become a spectacle already?); and finally, how the night continues beyond the club and after sunrise (what kinds of intimacies and gestures remain, how do we go back to the club after Orlando?).

New Books Network

Vacation Villages

Quite recently, a new kind of temporal heterotopia has been invented: vacation villages, such as those Polynesian villages that offer a compact three weeks of primitive and eternal nudity to the inhabitants of the cities. You see, moreover, that through the two forms of heterotopies that come together here, the heterotopia of the festival and that of the eternity of accumulating time, the huts of Djerba are in a sense relatives of libraries and museums. for the rediscovery of Polynesian life abolishes time; yet the experience is just as much the,, rediscovery of time, it is as if the entire history of humanity reaching back to its origin were accessible in a sort of immediate knowledge.

Foucault

Gated Communities

Like a permanent vacation village, the gated community is a phenomenon of the 21st century. In America, the same companies running prisons are guarding gated communities.

The ‘trailer park’ or the ‘mobile home community’ is a compulsory form of gated community — made compulsory due to poverty.

Rapunzel lives in the ultimate gated community. Rapunzel is the ur-Story of any overprotected girl who has lost freedom to move around her environment due to real or perceived danger.

Harlen Coben’s novel Safe was adapted for TV, starring Michael C. Hall, Michael C. Hall’s mish-mashed, weird-ass British accent, and a gated community which may not be so safe after all.

See also: Golf, gates and the good life: Johannesburg’s private estates offer home comforts, good service – and selective solidarity by Federica Duca, 8th November 2022

Religious Spaces

There are even heterotopies that are entirely consecrated to these activities of purification -purification that is partly religious and partly hygienic, such as the hammin of the Moslems, or else purification that appears to be purely hygienic, as in Scandinavian saunas.

Foucault

In a children’s book the tree house can function as a kind of religious space, letting in only those who perform the ritual of a password (e.g. Enid Blyton’s The Secret Seven). In The Three Investigators the boys have a caravan in one of their uncles’ scrapyard.

Religious Communities

The first wave of colonization in the seventeenth century, of the Puritan societies that the English had founded in America and that were absolutely perfect other places.

Jesuit colonies that were founded in South America: marvelous, absolutely regulated colonies in which human perfection was effectively achieved. The Jesuits of Paraguay established colonies in which existence was regulated at every turn. The village was laid out according to a rigorous plan around a rectangular place at the foot of which was the church; on one side, there was the school; on the other, the cemetery-, and then, in front of the church, an avenue set out that another crossed at fight angles; each family had its little cabin along these two axes and thus the sign of Christ was exactly reproduced. Christianity marked the space and geography of the American world with its fundamental sign.

The daily life of individuals was regulated, not by the whistle, but by the bell. Everyone was awakened at the same time, everyone began work at the same time; meals were at noon and five o’clock-, then came bedtime, and at midnight came what was called the marital wake-up, that is, at the chime of the churchbell, each person carried out her/his duty.

Thirteen-year-old Kyra has grown up in an isolated community without questioning the fact that her father has three wives and she has twenty brothers and sisters, with two more on the way. That is, without questioning them much—if you don’t count her secret visits to the Mobile Library on Wheels to read forbidden books, or her meetings with Joshua, the boy she hopes to choose for herself instead of having a man chosen for her.

But when the Prophet decrees that she must marry her sixty-year-old uncle—who already has six wives—Kyra must make a desperate choice in the face of violence and her own fears of losing her family forever.

Brothels

Brothels and colonies are two extreme types of heterotopia.

Foucault

In YA fiction featuring the heterotopies of brothels we have Naked by Stacey Trombley, Dime by E.R. Frank and Out of the Easy by Ruta Sepetys, among others.

‘Love’ Hotels

There are others, on the contrary, that seem to be pure and simple openings, but that generally hide curious exclusions. Everyone can enter into these heterotopic sites, but in fact that is only an illusion—we think we enter where we are, by the very fact that we enter, excluded. I am thinking for example, of the famous bedrooms that existed on the great farms of Brazil and elsewhere in South America. The entry door did not lead into the central room where the family lived, and every individual or traveler who came by had the right to open this door, to enter into the bedroom and to sleep there for a night. Now these bedrooms were such that the individual who went into them never had access to the family’s quarter the visitor was absolutely the guest in transit, was not really the invited guest. This type of heterotopia, which has practically disappeared from our civilizations, could perhaps be found in the famous American motel rooms where a man goes with his car and his mistress and where illicit sex is both absolutely sheltered and absolutely hidden, kept isolated without however being allowed out in the open.

For children, a hotel doesn’t have to be a sex destination in order for it to function as a getaway.

BEAUTY PAGEANTS

I would include the world of beauty pageantry as a heterotopia. This world is explored in films such as Little Miss Sunshine, Whip It! and Dumplin.

IS HETEROTOPIA A USEFUL CONCEPT FOR TALKING ABOUT CHILDREN’S LITERATURE?

The word is probably more useful for architects than for students of literature, because it describes the function of a real world fictional place such as a Spanish garden or a games room. The truth is, every story with elements of realism features a heterotopia. Some sort of closed arena is a requirement for a story, after all.

The word is still useful for students of literature and here’s why:

[Disneyland] is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, when in fact all of Los Angeles and the America surrounding it are no longer real, but of the order of the hyper-real and of simulation.

Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulations (1981)

Certain kinds of stories, including many children’s stories, are likewise presented as imaginary in order to make us believe the rest is real. Yet the very existence of these stories draws attention to the fact that the ‘real world’ is pretty far from ‘real’. We’re actually living in a simulacrum of reality.

When The Tiger Who Came To Tea leaves the house, the young reader’s attention is drawn to the fact that their real life is bound by certain rules and expectations. Foucault considered heterotopies escapes from authoritarianism, much like the carnivalesque settings in picture books. Subsequent thinkers have expanded his original meaning. Heterotopies can also be dystopias, in fiction as in real life.

Children’s literature in general is very concerned with truth. Middle grade fiction in particular is read at a time when children are learning not only to lie, but when it is okay to lie. The concept of heterotopia is useful when considering the difference between reality and a shiny veneer which is not genuine at all. Is this expensive boarding school your parents have sent you to really all that great? Does this teacher in charge of your welfare really have your best interests at heart? Do the ‘popular’ kids in your class have real friends, or does popularity really mean ‘social status’? Is this world created for you by adults anything like the world you’ll be thrown into once you enter adulthood?

All children — at least, all well-cared-for children — live in a heterotopia, where they are protected from certain news stories, from the full spectrum of adult sexuality, from toxic food choices and their own bad decisions. The best coming-of-age stories — not the ones solely concerned with losing one’s virginity — are at their base about a young person realising the extent to which they’ve been living inside a heterotopia, and how much they’re willing to come out of it.

Heterotopia is also a useful concept when talking about the ‘Disneyfication‘ of children’s stories. This has been going on for more than half a century, and is an interesting look into how the West thinks of childhood.

It is also useful for getting a handle on your own personal philosophy of children’s literature. To what extent are you comfortable with people/children living in multiple levels of reality? Do you think that when children read magical stories like Harry Potter this affects their real-world understanding of science? At what age should children be exposed to what? If we allow privileged child readers to remain in the heterotopia we have created for them will this affect how they identify with people less privileged than themselves?

Also, the words used to describe “non-realistic” narratives have not been specific enough. Academics were overlapping different words and using them interchangeably. This was no good. Take the word ‘fantasy’ itself. Different scholars call it a ‘genre’, a ‘style’, a ‘mode’, or a ‘narrative technique’. Believe it or not, people have big arguments about this. When describing children’s literature in particular, anything that’s not realistic is generally called either ‘fantasy’ (for long works) or ‘fairy tale’ (for short ones). This distinction is pretty useless really. Fairy tales and fantasy may seem related at a surface level, fairy tales came out of myth and have roots in archaic society. But fantasy is definitely a product of modern times. Heterotopia can be useful when talking about concepts related to modern fantasy stories, especially those with no portal. Portal fantasy most often has just the two distinct worlds — the ‘real world’ and the ‘fantasy world’ through the looking glass or whatever. But modern fantasy often involves a multitude of ‘secondary’ worlds. Traditional fantasy is all about simplicity, stability and optimism, whereas modern fantasy can explore reality in a much more complex fashion, emphasising uncertainty and ambiguity. Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials series is a good example of this kind of fantasy.

Perhaps it might be especially useful for talking about fabulism, magical realism, and especially the typical modern child’s relationship with computer games. The word ‘spaces’ is often used to describe the imaginary worlds of computer games but we might use ‘heterotopia’ to be more specific.

ISLANDS

Islands in literature are often considered a heterotopia — both a fantasy portal and a fantasy destination rolled into one.

PRISONS/JAILS

From a distance the prison might be an out-of-town shopping mall, Texas Homecare, Do It All and Toys ‘R’ Us. There’s a creche at the gate and a Visitors’ Centre, as it might be for Fountains Abbey or Stonehenge. Reasoning that I am a visitor myself, I big struggle across the windswept car park but when I put my head inside I find it full of visitors of a different sort, the wives and mothers (and very much the children) of the inmates, Birds of a Feather territory, I suppose. At the gate proper I’m frisked, X-rayed, my handprints taken, and am then taken through a series of barred gates and sliding doors every bit as intimidating as the institution in Silence of the Lambs.

Alan Bennett from Untold Stories

AIRPORT DEPARTURE LOUNGES

Talk to people on flights, starting at the boarding gate. Everyone is bored and alienated in airports, and you get the chance to meet people far outside your normal circles. Offer people gummy bears to break the ice.

Less Wrong

FURTHER READING

Heterotopic World Fiction: Thinking Beyond Biopolitics with Woolf, Foucault, Ondaatje

Note: Sadly, Dr. Marie-Christine Leps passed away before the book came out. Via this conversation, we pay homage to her work that went into the making of this book and to her memories.

After more than a century of genocides and in the midst of a global pandemic, Lesley Higgins and Marie-Christine Leps’s book Heterotopic World Fiction: Thinking Beyond Biopolitics with Woolf, Foucault, Ondaatje (Academic Studies Press, 2022) focuses on the critique of biopolitics (the government of life through individuals and the general population) and the counterdevelopment of biopoetics (an aesthetics of life elaborating a self as a practice of freedom) realized in texts by Virginia Woolf, Michel Foucault, and Michael Ondaatje. Their world fiction produces transhistorical, transnational experiences offered to the reader for collective responsibility in these critical times. Their books function as heterotopias: spaces and processes that recall and confront regimes of recognized truths to dismantle fixed identities and actualize possibilities for becoming other. Higgins and Leps define and explore a slant, biopoetic perspective that is feminist, materialist, anti-racist, and anti-war.

New Books Network