A fractured fairy tale is a story which makes use of a traditional fairy tale but restructures and reimagines, with the aim of greater nuance and with a contemporary sensibility in mind. The writer might be offering a critique of the ideas offered up in an earlier version. This makes some of them subversive. Fractured fairy tales are often aimed at an adult audience, though they’re common in children’s literature as well.

See this post on Postmodern Picturebooks. Fractured fairytales lend themselves to postmodern readings.

Sometimes called parodies or transformed tales, fractured tales are humorous or exaggerated imitations of an author, a particular traditional tale, or a style. Fractured tales are currently popular in picture book format. Beginning with The True Story of the 3 Little Pigs (1989). Jon Scieszka and Lane Smith began a trend that shows no sign of abating. Traditional tales from “Little Red Riding Hood” to the “Three Little Pigs” to “The House That Jack Built” have been retold in a humorous vein in picture book format. Picture book examples are The Dinosaur’s New Clothes (1999), illustrated by Diane Goode; Little Red Riding Hood: A New Fangled Prairie Tale (1995), illustrated by Lisa Campbell Ernst; The Little Red Hen Makes a Pizza (1999), illustrated by Amy Walrod: and Beauty and the Beaks: A Turkey’s Cautionary Tale (2007), illustrated by Mary Jane Auch.

A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and Using Picture Books By Denise I. Matulka

Another standout example of a fractured fairytale picture book, mentioned often by literature academics: The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales by Scieszka and Smith. The story’s aim is meta, drawing the reader’s attention to the fact that these are just stories, and whatever meaning they seem to imply should be interrogated. The ‘meaning’ of these ‘stupid tales’ is constructed by the reader.

When classic tales are revisioned to deliberately poke fun at the form, we call them ‘fractured’, but classic tales are always, forever undergoing evolution, even when the re-teller doesn’t intend any changes:

Retelling stories is about as old as storytelling itself. Each generation’s storytellers takes elements from stories they heard as children. They’ll mash those elements with their own ideas and suddenly the story becomes something completely new. No story has survived untouched throughout the ages — even the so-called “classic” fairy tales do this. If you’re familiar with the Greek story of Cupid and Psyche there are an awful lot of similar elements from that tale in the French story “Beauty and the Beast” as well as in “Cinderella.” And elements of “Beauty and the Beast” also turn up in the Norse tale “East of the Sun, West of the Moon.” Storytellers love to take familiar plots and give them a twist. When you take an existing story and adapt it for your own you are making a connection — a connection with every storyteller who told their own version of that story, and a connection with every audience that has loved some variation of that story. It allows the writer to create a kind of shorthand with the audience — if you like “x,” then you’ll find familiar things in this new version of the story. We take comfort in the familiar and relish the new that’s mixed in, and something fresh and original is created from that mixture.

Christina Henry

Fractured fairy tales can be of any genre, written for any demographic:

- Fantasy — Most recently we’ve had a lot of dark fantasy

- Horror — Horror has gone hand-in-hand with the dark fantasy. In horrors, villains such as witches don’t tend to have a back story — they serve as the evil force.

- Dramatic musical

- Thriller

- Comedy (Parody)

Fractured fairy tales are very popular at the moment, for young adults and adults. In film and television there was a proliferation between 2010 and 2016, and many of these are available on Netflix, for example.

- Into The Woods — a stage play running for two years from 2002 by Steven Sondheim which weaves Grimm and Perrault tales together; produced for screen during the ‘proliferation’ period.

- Once Upon A Time

- Grimm

- Shrek — This franchise takes a classic monster from a fairytale (the ugly ogre) and turns him into a sympathetic character.

- Descendents

- Beastly — a retelling of the fairytale Beauty and the Beast and is set in modern-day New York City.

- Maleficent — a retelling of Sleeping Beauty from the evil fairy’s point of view.

- Hansel and Gretel — horror

- Witch Hunters — horror

- Snow White and the Huntsmen — horror

- Half Baked — horror

Three Types Of Fractured Fairytale

The Cross-over Narrative

Cross-over fractured fairytales intersect various fairy tales to create one big story. Examples are Into the Woods, Once Upon a Time and Grimm.

The Subversive

Subversive fractured fairy tales force the viewer to look at a familiar story from a unique perspective. Examples are Beastly and Maleficent. Often these subversive tales take on the narrative point of view from a different angle — perhaps the viewpoint character is the villain, recast as a sympathetic character. It’s rare for witches to have backstories in the traditional tales, but modern fractured retellings often give us the witch’s perspective.

Many tales which aim to be subversive nevertheless uphold traditional ideas:

- Youth is beauty

- Age is ugly and to be avoided

- It’s not so bad being ugly, but your ugliness still prevents you from marrying someone beautiful (Shrek)

Moral relativism is the view that moral judgments are true or false only relative to some particular standpoint (for instance, that of a culture or a historical period) and that no standpoint is uniquely privileged over all others. Subversive fractured fairy tales tend to take this view. Sure, Maleficent is evil, but once we know her back story, the morality changes. A common technique in retelling old tales from different perspectives is to name previously unnamed characters.

Naming has primary importance as a way of determining a being’s subjectivity. [A character’s namelessness] reinforces his lack of an existence, his lack of agency.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Waking Sleeping Beauty

So wicked witches are named, Cinderella is known to us by her more familiar name, Ella and so on. Subversive tales can be juxtaposed against another type of ‘re-visioning’, described by Jack Zipes:

There are literally hundreds of publishers who produce and market cheap versions of the Grimms’ tales as pretexts to conceal their profit-making motives. These duplications merely reinforce static nations of the nineteenth-century fairy tales and leave anachronistic values and tastes unquestioned. Whatever changes are made in these duplications—and changes are always made—they tend to be in the name of an ignorant conservatism that upholds arbitrary notions of propriety, for many people believe that there is such a thing as a “proper” Grimms’ fairy tale. In contrast, the reversions of the Grimms’ pre-texts, to use the terms coined by Stephens and McCallum, adulterate the Grimms’ tales by adding ingredients, taking away some elements, and reconstructing them to speak to contemporary audiences in different sociocultural contexts.

Jack Zipes, Sticks and Stones

The Inspired

Inspired fractured fairy tales are only loosely based on traditional stories. Examples are Hansel and Gretel (the film), Witch Hunters, Snow White and the Huntsman.

Jane Campion’s The Piano is loosely inspired by “Bluebeard“, but is nonetheless obvious with the play-within-a-play structure. Robin Black’s short story “Pine” is even more loosely Bluebeard-ish, but still there. These things sit on a continuum.

Angela Carter often uses a title as clue to her inspiration, but then blows away the plot. Carter’s “Erl-King” is inspired by Goethe’s poem without adhering to the original beats.

Hello! Project’s Minimoni starred in a drama based on “The Musicians Of Bremen“. In Japanese it’s called Mini Moni.de Bremen no Ongakutai (Mini Moni’s Bremen Town Musicians). This adaptation goes backwards in time through three periods of Japanese history unveiling the story. The drama is inspired by the Bremen tale but does not have much in common with it.

A TAXONOMY OF FRACTURED FAIRYTALES

Kevin Paul Smith (2007) drew on French literary theorist Gerard Genette’s theories to identify eight categories of intertextual use of fairy tales:

- Authorised: Explicit reference to a fairytale in the title

- Writerly: Implicit reference to a fairytale in title

- Incorporation: Explicit reference to a fairytale within the text

- Allusion: Implicit reference to a fairytale within the text

- Re-vision: putting a new spin on an old tale

- Fabulation: crafting an original fairytale

- Metafictional: discussion of fairytales

- Architextual/Chronotopic: “Fairytale” setting/environment

STORIES WHICH MAKE USE OF FAIRYTALE SYMBOLISM

The term ‘fairytale’ is often used as an epithet—a fairytale setting, a fairytale ending—for a work that is not in itself a fairy tale, because it depends on elements of the form’s symbolic language.

Marina Warner (2014) (xviii)

I have argued that Animal Kingdom (the American TV series) and Breaking Bad make heavy use of fairytale symbolism, but other viewers may not see it; meanwhile, other viewers may see fairytale symbolism in shows where I do not. Many stories have deep fairytale links, and it’s only a matter of making the connection.

You can find many examples of scholars who talk about fairytales in terms of symbolism and motif and the importance of fairytale archetypes to human psychology.

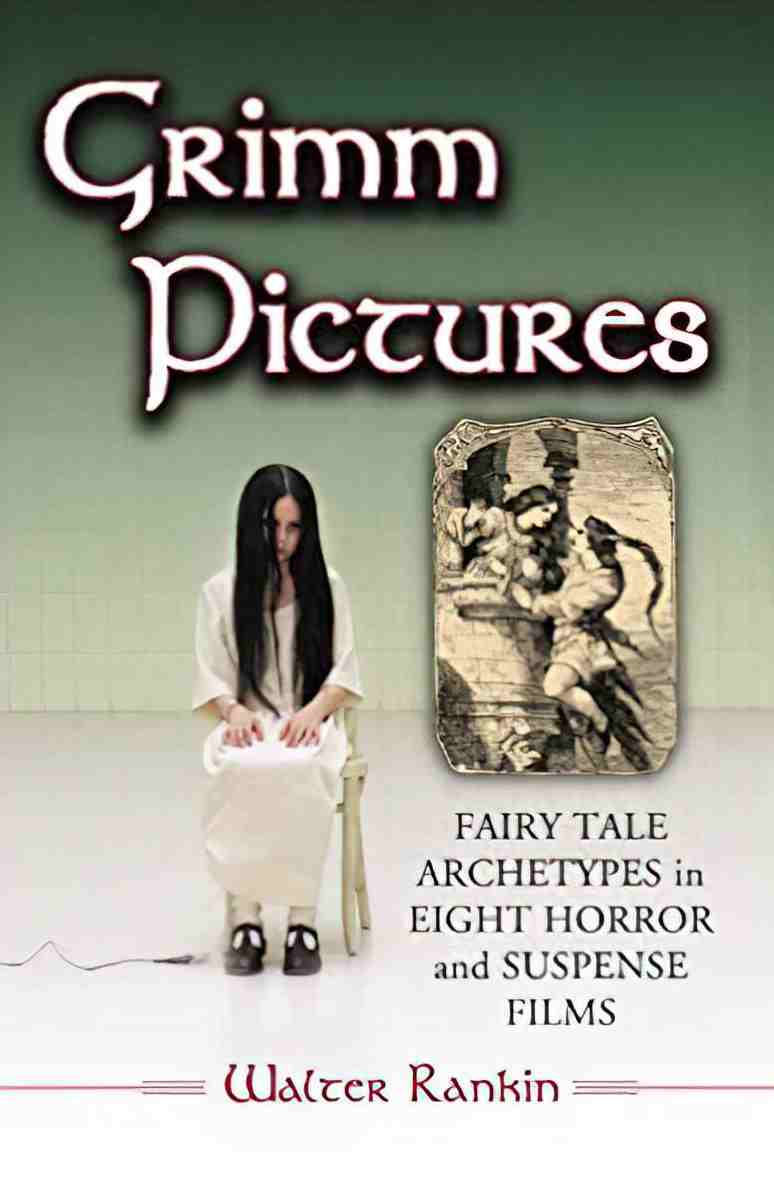

See for example Walter Rankin’s Grimm Pictures: Fairy Tale Archetypes in Eight Horror and Suspense Films (2007).

Though Grimm’s Fairy Tales was published about 200 years ago, the revered collection of folk stories remains one of the most iconic pieces of children’s literature and has had significant influence in modern pop culture.

This work examines the many ways that recent films have employed archetypal images, themes, symbols, and structural elements that originated in the most well-known Grimm fairy tales. The author draws similarities between the cannibalistic symbolism of the Grimm brothers’ Little Red Cap and the 1991 film The Silence of the Lambs and reveals Faustian parallels between Rumpelstiltskin and the 1968 film Rosemary’s Baby.

Each of eight chapters reveals a similar pairing, and film stills and illustrations are featured throughout the work.

Importantly, a narrative isn’t complete until it is interpreted by its audience. We might even say there’s no such thing as a symbolically fairytale text, only a symbolically fairytale reading of a text.

POTENTIAL PROBLEMS WITH FRACTURED FAIRYTALES

When writers take an old tale and subvert expectations, wonderful things can be done. Worldviews can be modified or even shattered. But because these stories are so powerful, they can also be unhelpful.

ALISON HALDERMAN: Science fiction likes to take traditional old fairy tales and magic and to explain them in a scientific context.

URSULA LE GUIN: I don’t like that at all. Things like Chariots of the Gods? [by Doris Lessing, 1979] really put me off. It’s not a real explanation. It seems to destroy the magic when people try to give scientific rationalisations. That’s different from taking an old myth and dressing it up in new metaphors.

The Last Interview

FREE (ONLINE) EXAMPLES OF FRACTURED FAIRY TALES CREATIVE WRITING

Although “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” is a legend rather than a fairy tale, my feminist fractured take “The Magic Pipe” was longlisted for The Commonwealth Short Story Prize in 2019.

See also “Lotta: Red Riding Hood“, co-written with a friend of mine. We humanise Little Red Riding Hood by giving her a name.

FURTHER READING

The Horns and Wings of Maleficent by Jamie Armstrong at Popular Culture and Theology

Fairy Tales in Contemporary American Culture: How We Hate to Love Them

In the twenty-first century, American culture is experiencing a profound shift toward pluralism and secularization. In Fairy Tales in Contemporary American Culture: How We Hate to Love Them (Lexington Books, 2021), Kate Christina Moore Koppy argues that the increasing popularity and presence of fairy tales within American culture is both indicative of and contributing to this shift. By analysing contemporary fairy tale texts as both new versions in a particular tale type and as wholly new fairy-tale pastiches, Koppy shows that fairy tales have become a key part of American secular scripture, a corpus of shared stories that work to maintain a sense of community among diverse audiences in the United States, as much as biblical scripture and associated texts used to.

In this interview with New Books Network, author Kate Koppy and host Carmen Gomez-Galisteo talk about Fairy Tales in Contemporary American Culture: How We Hate to Love Them and how they are relevant in today’s society, despite some parents’ and educators’ misgivings that they may instil traditional, outdated values into children.

New Books Network

The Folkloresque: Reframing Folklore in a Popular Culture World

This volume introduces a new concept to explore the dynamic relationship between folklore and popular culture: the “folkloresque.” With “folkloresque,” Foster and Tolbert name the product created when popular culture appropriates or reinvents folkloric themes, characters, and images. Such manufactured tropes are traditionally considered outside the purview of academic folklore study, but the folkloresque offers a frame for understanding them that is grounded in the discourse and theory of the discipline. Fantasy fiction, comic books, anime, video games, literature, professional storytelling and comedy, and even popular science writing all commonly incorporate elements from tradition or draw on basic folklore genres to inform their structure. Through three primary modes–integration, portrayal, and parody–the collection offers a set of heuristic tools for analysis of how folklore is increasingly used in these commercial and mass-market contexts. Michael Dylan Foster and Jeffrey A. Tolbert‘s edited collection The Folkloresque: Reframing Folklore in a Popular Culture World (Utah State University Press, 2015) challenges disciplinary and genre boundaries; suggests productive new approaches for interpreting folklore, popular culture, literature, film, and contemporary media; and encourages a rethinking of traditional works and older interpretive paradigms.

New Books Network

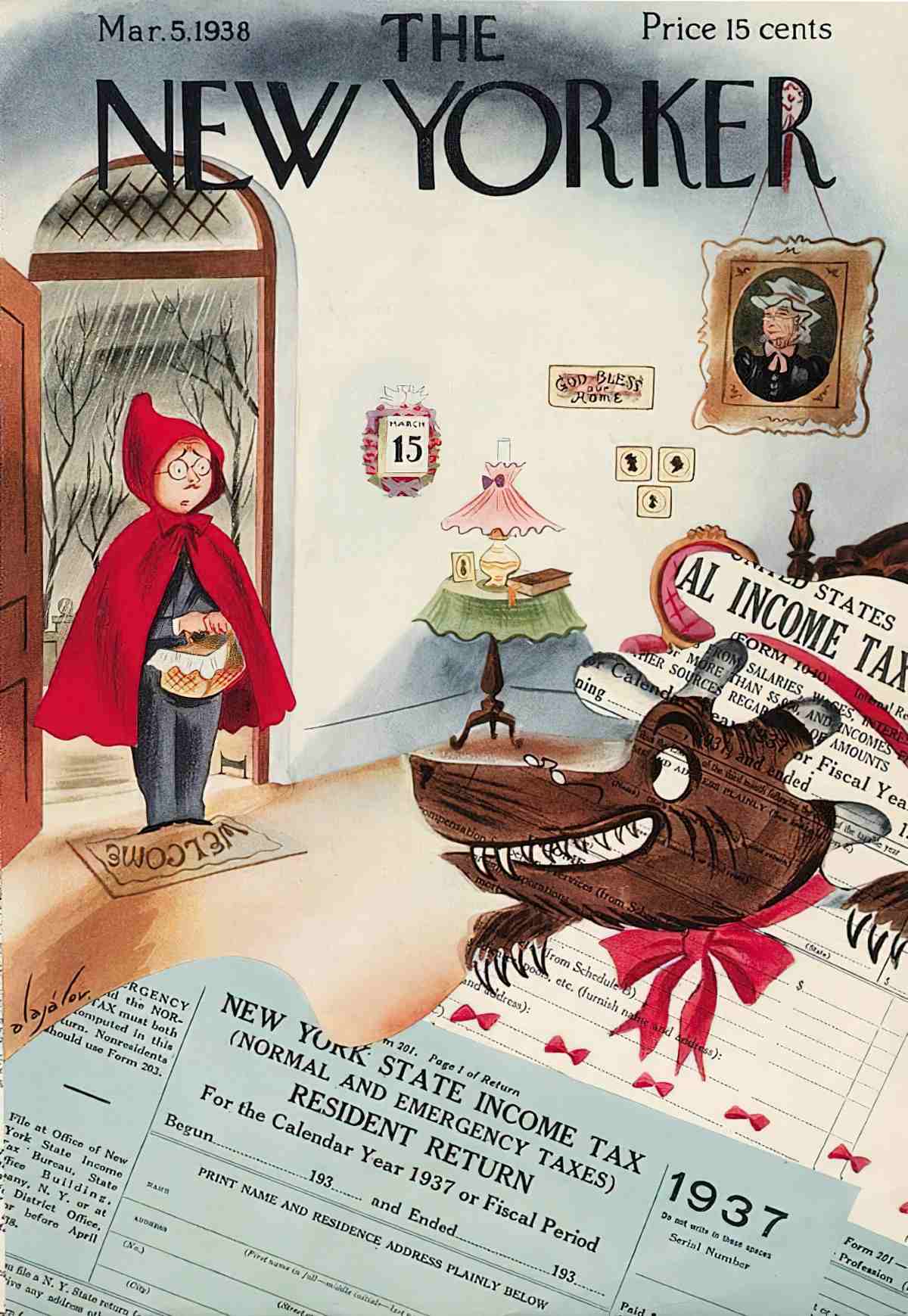

Header: Constantin Alajalov (1900-1987) The New Yorker cover March 5, 1938