Ruben Östlund’s Triangle of Sadness is a disturbing mash-up of Lord of the Flies, reality TV series Below Deck and Alex Garland’s The Beach.

But when it comes to the ending, another work of fiction comes to mind.

TRIANGLE OF SADNESS AND KING RAT

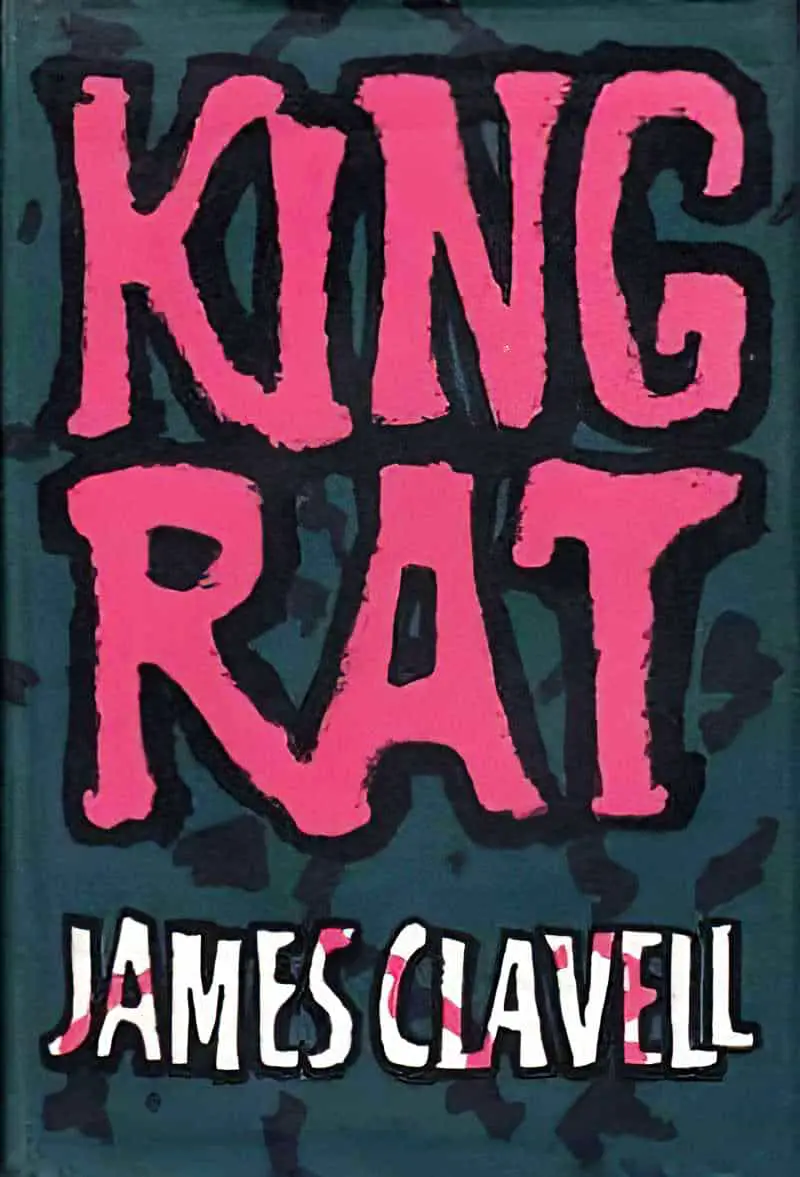

I wonder if modern audiences remember another tentpole story from the 20th century: King Rat, the 1962 novel by James Clavell, later adapted for film. In Clavell’s story, an American man with no power in the civilian world finds an untapped power once imprisoned inside a WW2 Japanese concentration camp in Changi. There, he becomes king pin for his ability to make meals out of rats, ensuring he and his compatriots survive nutritionally.

The time is World War II. The place is a brutal prison camp deep in Japanese-occupied territory. Here, within the seething mass of humanity, one man, an American corporal, seeks dominance over both captives and captors alike. His weapons are human courage, unblinking understanding of human weaknesses, and total willingness to exploit every opportunity to enlarge his power and corrupt or destroy anyone who stands in his path.

You’ll see the correlation. Abigail is the King Rat in Triangle of Sadness. Working as a low-status cleaner in her everyday life, she is the only one possessed with the skills for survival when the luxury motor yacht is attacked by pirates, leaving a handful of survivors who wind up together on a nearby island.

At the end of King Rat, the once powerful King of the Concentration Camp doesn’t want to leave. Of course, everyone else can’t wait to get out and return home, but King Rat has no home. He would rather have the status and continue living on rats.

ABIGAIL’S CHARACTER ARC

Like Clavell’s King Rat character, Abigail cannot bear going back to her life, where she must work for survival as a slave, bossed around by the undeserved mega-wealthy. We first saw Abigail’s basic contempt for the passengers when she interrupted the young model couple. Yaya and Carl wanted to sleep in rather than get their room cleaned, and refused to commit to a getting-out-of-bed time.

When Abigail washes up on the island, at first she seems to be in shock. However, she was the only one on the entire yacht who had the wherewithal to find the emergency boat and get into it. We understand from the start that she possesses survival instinct.

WHY WAS CARL RUNNING AT THE END OF TRIANGLE OF SADNESS?

The injured German woman in the raft has just met with that local guy selling his wares and realised the marooned party is not so ‘marooned’ after all. They’re actually very close to civilisation. Although she’s unable to communicate to the peddler that she and her fellow yacht passengers need help, it’s highly likely that she is somehow able to communicate that to the other stranded passengers when she sees them.

Director Ruben Östlund has himself said on record that Carl is probably running to Yaya and Abigail to inform them of the news that they are not alone on the island. Either that, or he’s realised the other side of the island must be inhabited, and he’s simply running towards civilisation.

It was simply by coincidence that Abigail found the elevator at around the same time the injured German woman encountered the peddler. (We accept this coincidence in fiction, though there are complicated rules around acceptable coincidence in storytelling.)

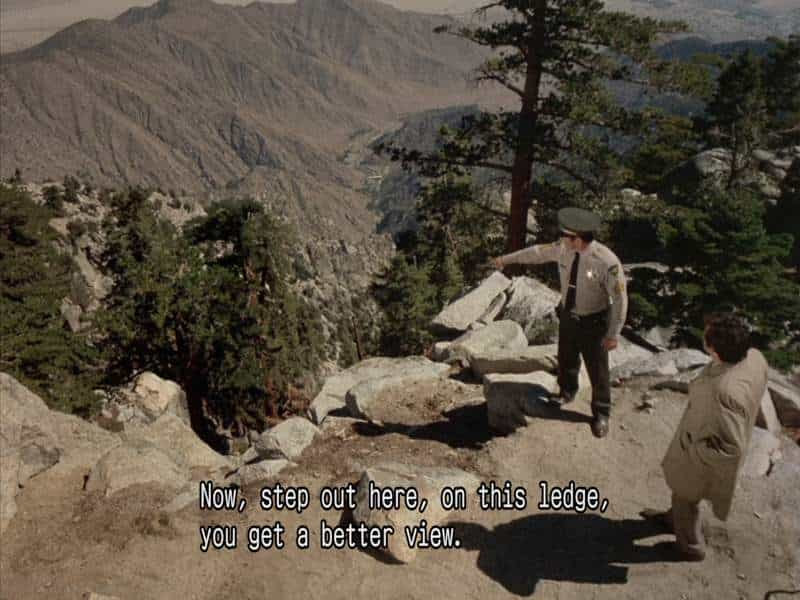

It’s also possible that Carl senses something up with Abigail. He knows that Abigail has a ruthless streak, and that the power has gone to her head. He looked uneasy when Abigail told him she’d like some time alone with Yaya. This unease transfers to the audience when we’re shown shots such as a low-angle of Yaya taking a break on a precarious rocky outcrop.

I got a stone thrown to my head. I was briefly hospitalised for that. Luckily I had a helmet on and I still blacked out. And there was something visceral about a rock in your head. Because rock is a symbol of powerlessness. David and Goliath. And it was this encounter with Gaza’s rage. I also had a very complicated experience. I came to respect these Palestinian teenagers who were throwing rocks at my friends and me. We were armed. There was a great deal of courage. I recognised myself as a teenager in their rage. I was a very strong participant in Jewish activism when I was a teenager in the sixties and the early seventies … I identified to some extent with these kids and I felt this grudging respect for them.

Yossi Klein Halevi on The Ezra Klein Show talking about the Israeli Palestine war of 2023

It is no surprise to us when Abigail develops murderous intentions towards Yaya because the director set it up that way. As an established empathetic character right from the start of the film, we assume Carl gets the same vibes as we do, even though he has access to different information.

DOES ABIGAIL KILL YAYA WITH THE ROCK?

The image of Abigail bent low, stepping towards the camera (towards Yaya) is one of the most beautifully horrific camera angles I’ve seen in horror.

We’ve just witnessed Yaya try to comfort Abigail. Yaya must know, at some level, that this is the end for Abigail’s reign. Unlike the young and beautiful Yaya, who is sufficiently self-aware to know that she is an expert manipulator, Abigail has nothing in the ordinary world except latent narcissistic tendencies which came to the fore in this single, never-to-be-repeated respite in her life. This was Abigail’s once-in-a-lifetime Island Vacation, a darkly carnivalesque holiday.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF ABIGAIL’S AGE

If you’ve seen enough episodes of Below Deck, you’ll have noticed that working on luxury yachts is a job for young people. There are several reasons for this:

- The hard physical labour and long days, requiring young muscles and excellent joints and balance;

- The beauty requirement, which diminishes in us all as we age

But there’s another reason why the job isn’t great for older people: There are only so many years you can put up with the ridiculous demands of horrible people. Australian chief stew Hannah Ferrier grew visibly more jaded as she continued to work as a yachtie into her thirties, and was eventually pushed out.

At 37, I don’t think of myself as old, but this job makes me feel it. There is a double stigma attached to being a minimum-wage worker of middle age. It is a trope on screen, used to signify free-market malfeasance or personal disaster. In life it offends our notion of progression, the capitalist credo that hard work yields rewards. Perhaps this is why our customers are so rude. And after a long night biting down the urge to answer back, it feels good to rack up a few lines and speak your mind. I never appreciated this in my old job at the magazine: the privilege of being paid to communicate. People in service roles are paid, in part, to shut up. Holding your tongue, in the face of provocation, is a skill. It’s a shame the market doesn’t value it.

Cocaine, class and me: everyone in this town takes drugs, all the time – they’re part of the civic culture, Tabitha Lasley

The character of Abigail is much older than Hannah was when she left, and we can assume she’s even more jaded. Cleaners earn more on luxury yachts than for the same work literally anywhere else, so the yacht income can become an addiction.

ABIGAIL’S ADDICTION

And Abigail has an addictive personality. Controlling the others goes beyond survival strategy for her — she doesn’t need a hot young guy to have sex with; simply wants him, and she wants to assert her dominance over Yaya. She quickly becomes addicted to ‘narcissistic supply‘.

So when we see Abigail with the rock over her head, we’re watching an addict about to have her supply cut off.

Abigail’s reflection character is the Russian guy who made his fortune from ‘selling sh!t’. He goes the opposite direction. Ordinarily used to wealth and power, he almost seems to enjoy the chance to bond with others at a human level. He becomes more appealing as the film goes along.

Östlund’S USE OF FORESHADOWING

Throughout the film, Ruben Östlund has utilised foreshadowing to indicate what’s coming next. Sometimes it’s not foreshadowing per se, but what I prefer to call set-up and pay-off. (Long story short, foreshadowing is metaphorical by definition.)

- Set-up and pay-off: An oblivious couple who made their fortune selling war devices which kill people [SET-UP] are the first to be killed with a hand grenade, which may or may not have been produced by their own factory [IRONIC PAY-OFF].

- Foreshadowing: The wife of the Russian guy coaxes a stewardess into the spa pool in a ridiculous game in which the status is temporarily ‘overturned’. This is ridiculous because it can never be more than a game; paradoxically, the stewardess has no choice but to follow the wealthy passenger’s commands to ‘be the boss’ for a while. This works at a metaphorical (foreshadowing) level when we compare the very temporary flip in power which happens on the ‘deserted’ island later.

When it comes to Abigail, Yaya and that ominous rock, is Ruben Östlund working with metaphor here, or was the earlier (horrific) murder of the donkey (also done with a rock) functioning as a set-up?

If the donkey scene was a (non-metaphorical) set-up, then Abigail got the idea to kill Yaya with a big rock from that scene, and lost all empathy for her fellow human beings during the little after party held afterwards, in which the party members held a competition to see who could draw the best donkey on a rock face. They held that little campfire event to defer the trauma that would otherwise come from killing a helpless animal in that way.

If the donkey murder was a set-up, we can assume Abigail went ahead and killed Yaya with that rock.

Except why is she crying? Does she have it in her to kill a human being? The fact is, we simply don’t know. The donkey and all the images of rocks definitely had the metaphorical effect of comparing different forms of murders, and increased tension for the audience, but with metaphor there doesn’t need to be the ‘satisfying click’ of ‘pay-off’.

THERE ARE TWO MAIN TYPES OF ENDINGS

If you read lyrical short stories you’ll be very familiar with how writers leave endings open. These types of endings are sometimes called ‘aperture endings’. They are a collaboration between storyteller and audience.

For more on short story endings, see this post.

EMOTIONAL CLOSURE

Importantly, stories don’t work unless writers give audiences emotional closure. And the director of Triangle of Sadness does give us that.

Meaning: We fully understand how Abigail feels at the end, even if we don’t empathise with her. We also understand how relieved Yaya must be to have stumbled across that ‘luxury elevator’, where she can re-enter a world where she is perfectly adapted to shine.

We also understand the admixture of terror and excitement Carl must feel as he sprints to find Yaya and Abigail on the other side of that island.

HERMENEUTICAL CLOSURE

What we don’t get is hermeneutical closure. (Hermeneutical basically means interpretative.)

Audiences never learn whether Abigail kills Yaya with that rock.

We don’t even know if Yaya senses Abigail’s murderous intention as she crouches right behind her on that beach.

In any case, the film fades to black before Abigail makes her moral decision:

- Return to a life of servitude (even as Yaya’s ‘personal assistant’)

- Live alone on the island forever… more likely hunted by police for the heinous murder of an Insta-famous young model.

What would you do in Abigail’s position? That’s the question for us all.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

If you really enjoyed Triangle of Sadness, I highly recommend The White Lotus, another highly ironic commentary on privilege, wealth and exploitation.

Island Symbolism in Storytelling