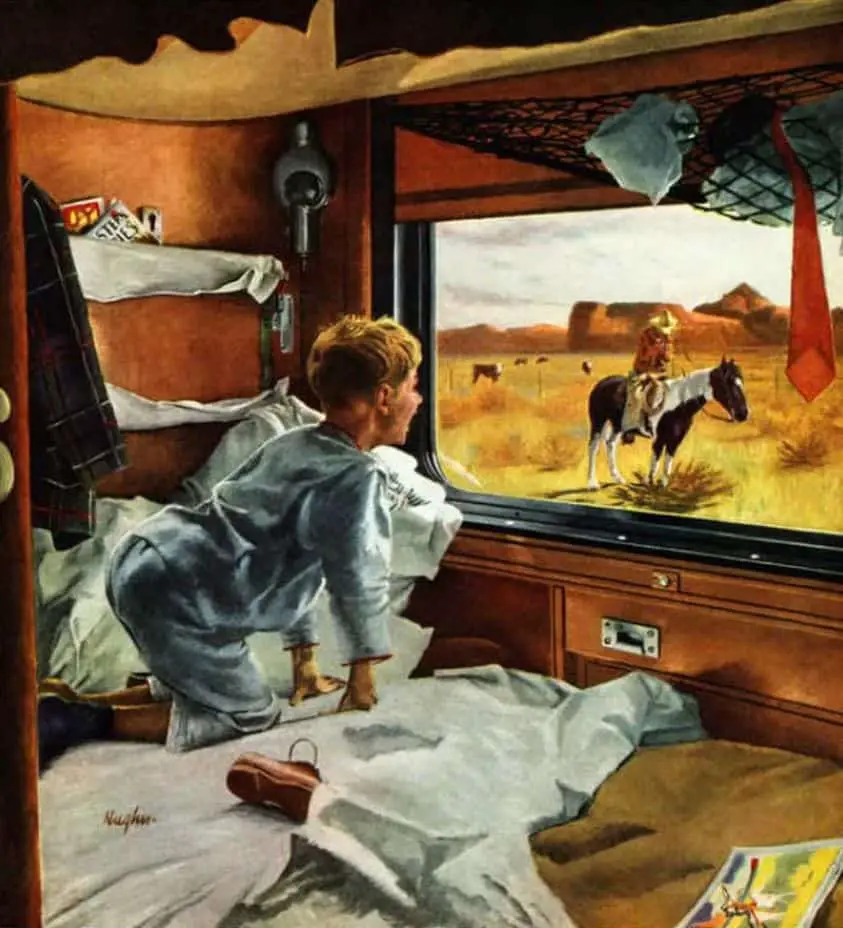

Western is a genre set primarily in the latter half of the 19th and early 20th century in the Western United States, the “Old West”. Before WW2, these stories were a celebration of American expansionism.

But since the war, almost every “Western” is actually an anti-Western. Rather than romanticising the expansion into the West, anti-Westerns focus on the harshness of the landscape, the death and the despair.

Bonana Girl by Patricia Beatty (1962)

Katherine Scott, a widow, leaves Portland, Oregon, with her two children for the Idaho gold fields thinking she’ll make a living teaching school. But when they get there, they discover there’s no children, there’s no place to live but in a tent, and there’s nothing to eat but beans.

Neo Western is a subgenre of the Western that adopts the character archetypes, settings, and themes of classic Westerns, but transplants them to appeal to contemporary sensibilities.

For more than fifty years, one third of all films released in the United States were westerns. They could be made cheaply, and a certain proportion of the male population could be predictably counted on to see them.

Howard Suber (who notes the exact same thing about horror films which came later)

Rifles for Watie (1957)

Jeff Bussey walked briskly up the rutted wagon road toward Fort Leavenworth on his way to join the Union volunteers. It was 1861 in Linn County, Kansas, and Jeff was elated at the prospect of fighting for the North at last.

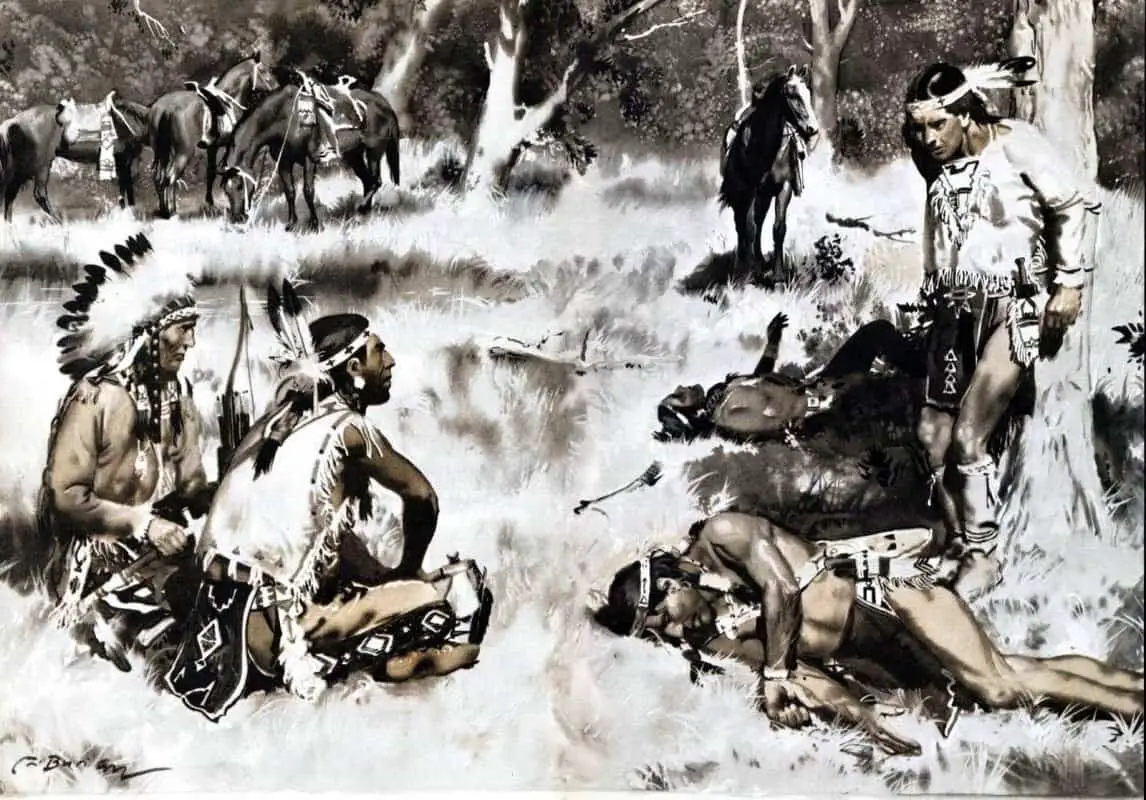

In the Indian country south of Kansas there was dread in the air; and the name, Stand Watie, was on every tongue. A hero to the rebel, a devil to the Union man, Stand Watie led the Cherokee Indian Nation fearlessly and successfully on savage raids behind the Union lines. Jeff came to know the Watie men only too well.

He was probably the only soldier in the West to see the Civil War from both sides and live to tell about it. Amid the roar of cannon and the swish of flying grape, Jeff learned what it meant to fight in battle. He learned how it felt never to have enough to eat, to forage for his food or starve. He saw the green fields of Kansas and Okla-homa laid waste by Watie’s raiding parties, homes gutted, precious corn deliberately uprooted. He marched endlessly across parched, hot land, through mud and slashing rain, always hungry, always dirty and dog-tired.

Why The Western Needs To Come Back: Arguments For

- From its inception, the Western has been key to the communication of America’s national ideals and the mythologizing of its past and present.

- A resurgence of the genre that does best at forcing America to reckon with itself is sorely needed.

- Focusing its attentions on what motivates rural-dwellers and keeps them up at night is what the Western was born doing, and so more films in the vein of Hell or High Water could bring us closer to understanding the parts of America we don’t hear much about outside of election season — even if we don’t like what they show us.

- The particular vulnerability of Native American communities in the face of the environmental threats posed at Standing Rock has been highlighted elsewhere, but I think it deserves cinematic attention from the Western, too.

from Film School Rejects

Brief History Of The Western

- The heyday of the Western genre was from about 1880 to 1960. The Western film goes through phases of popularity and has been particularly popular in the 1930s and the 1950s and 1960s. There has been a recent resurgence of the popularity of (neo-)Western novels with the TV series Longmire.

- The conflicts in westerns, horror, gangster, and science fiction films must end in a man-to-man, man-to-moment, or man-to-machine climax.

- The Great Train Robbery (1903)

- Edwin S. Porter‘s film starring Broncho Billy Anderson, is often cited as the first Western

- Shane is an example of a film which uses every single Western symbol without irony.

The popularity of the Western for adult readers has been mirrored by the rise then the fall of cowboy stories for children. Jerry Griswold, with fond memories of his cowboy story childhood writes, “My hope is that with pirates making a comeback, cowpokes can’t be far behind. All it really takes is a few parents ready to provide a stick horse, a cowboy hat, and stories like these.”

If cowboys (with extra girls) do come back into fashion, it will be interesting to see how authors and illustrators deal with the invasion aspect behind the glamour. Perhaps these stories are for Native American writers to write.

The 7 Plots Of Classic Westerns

Author and screenwriter Frank Gruber listed seven plots for Westerns:

- Union Pacific story. The plot concerns construction of a railroad, a telegraph line, or some other type of modern technology or transportation. Wagon train stories fall into this category. (CLASSICAL WESTERN)

- Ranch story. The plot concerns threats to the ranch from rustlers or large landowners attempting to force out the proper owners. (WESTERN DRAMA)

- Empire story. The plot involves building a ranch empire or an oil empire from scratch, a classic rags-to-riches plot. (CLASSICAL WESTERN)

- Revenge story. The plot often involves an elaborate chase and pursuit by a wronged individual, but it may also include elements of the classic mystery story. (WESTERN CAT-AND-MOUSE)

- Cavalry and Indian story. The plot revolves around “taming” the wilderness for white settlers. (CLASSICAL WESTERN)

- Outlaw story. The outlaw gangs dominate the action. (WESTERN CRIME)

- Marshal story. The lawman and his challenges drive the plot. (WESTERN DETECTIVE)

The Western Gothic

Lee Clark Mitchell suggests that ‘the Western had so little to do with an actual West that it might better bethought of as its own epitaph.’ The genre’s fascination with one limited but highly aggrandized facet of American history feels rather like it is trying to conjure a phantom, summoning an illusory frontier to life through recurrent representation. As such, Westerns, with their repetitions, their constricted representations of masculinity and their unremitting fixation with violence, provide a cultural landscape, one littered with bodies, that yields ripe territory for Gothicisation.

Helena Bacon

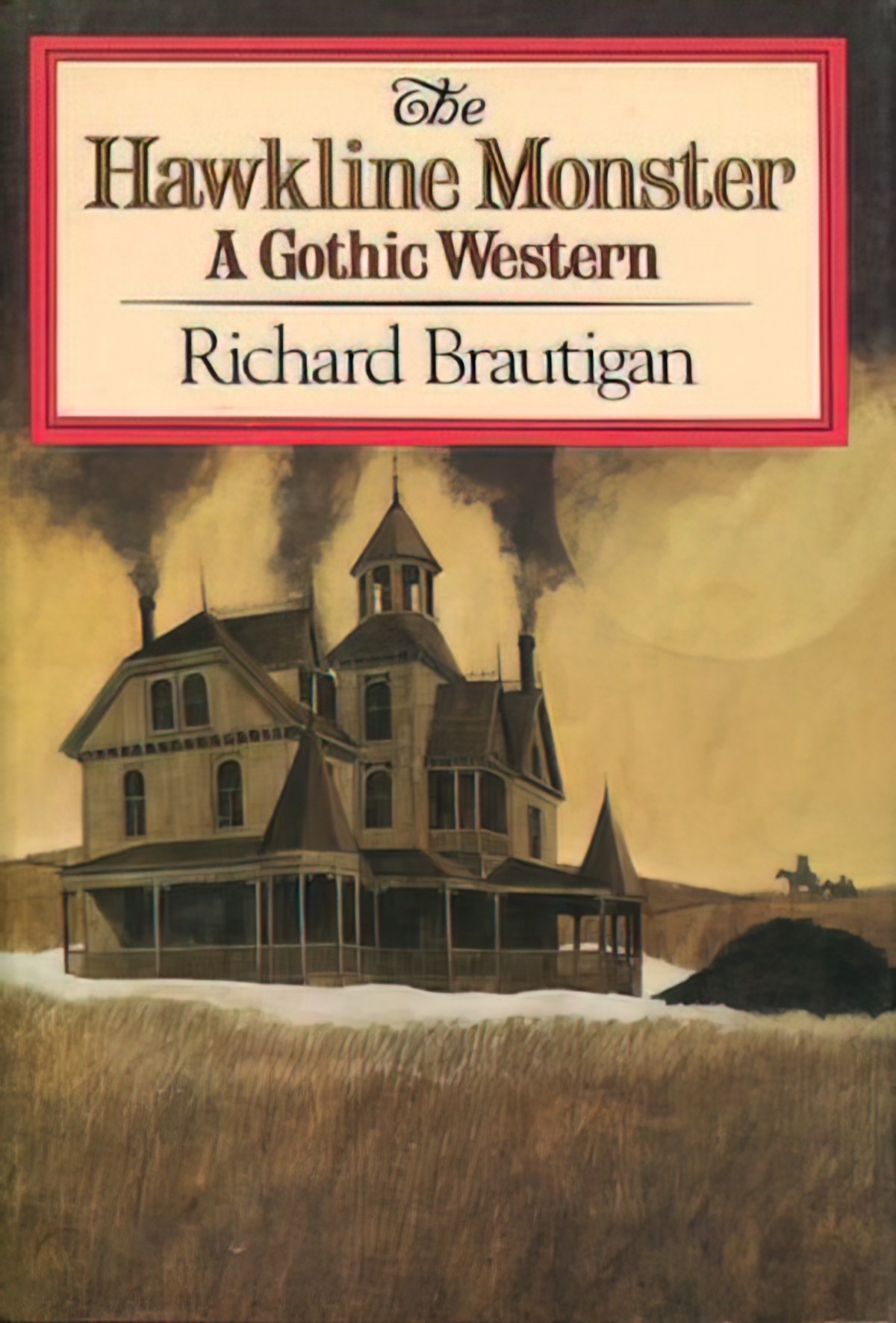

Example of Western Gothic: The Hawkline Monster (1974). The Hawkline Monster: A Gothic Western is a 1974 novel by Richard Brautigan. This work parodies Western and Gothic novels.

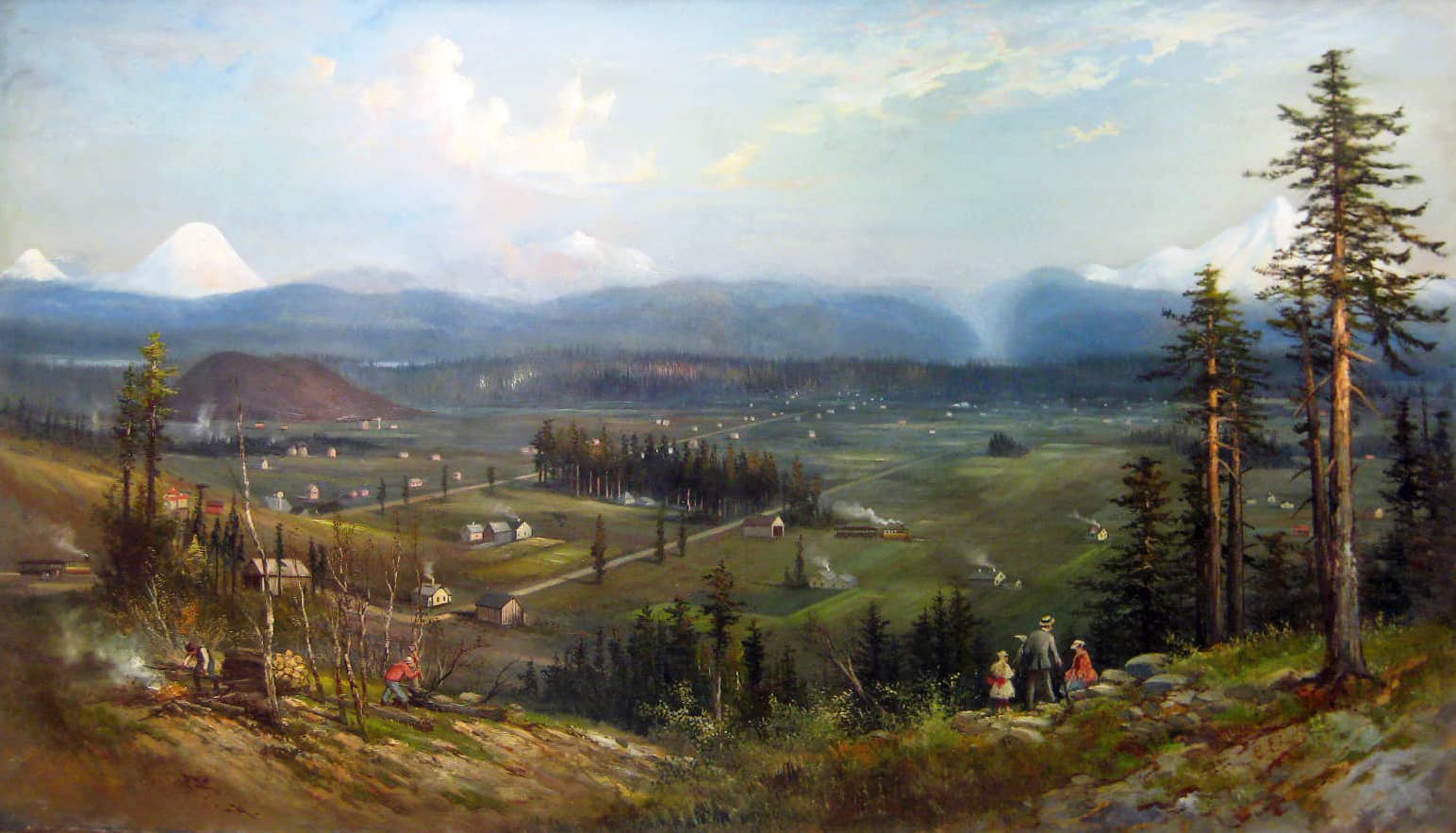

Setting Of A Western

- The setting of a classic Western will be in the latter half of the 19th Century in the American Old West, often entering on the life of a nomadic cowboy or gunfighter. Westerns often stress the harshness of the wilderness and frequently set the action in an arid, desolate landscape of deserts and mountains. Specific settings include ranches, small frontier towns and saloons of the Wild West. Some are set in the American colonial era.

- Characters also include Native Americans, bandits, lawmen, outlaws and soldiers.

Throughout most of human history, towns were situated next to dependable rivers. Western towns in films such as High Noon, The Searchers, The Wild Bunch, and Unforgiven, however, are situated in the middle of some of the driest places on earth. Perhaps that’s because deserts, in the Hebrew, Christian, and Islamic Bibles, are places of spiritual conflict.

Howard Suber

In a Classic Western You’ll Also Find

- A rational grid of clapboard buildings on the flat, dry plain of the Southwest

- A bustling community under the benevolent gaze of the marshal

- A showdown, which happens in the middle of the main street where everyone can see the hero’s bravery. The cowboy hero waits for the bad man to draw first, still beats him, and reaffirms right action and law and order for the growing community.

- The modern Western story is really a mixture of other genres with a setting in the latter half of the 19th Century in the American Old West, or a similarly desolate but modern American setting.

The Following Genres Can All Be Found Mixed With Myth:

- Crime/Detective (The Streets of Laredo)

- Love (Lonesome Dove) — also an anti-Western (dependent on audience interpretation)

- Thriller (No Country For Old Men, a neo-Western)

- Domestic Drama (The Power of the Dog)

Filming Locations Of Westerns

A spaghetti Western was filmed in Italy, where the landscape looked enough like America but was a lot cheaper to use as a location. Red Westerns (a.k.a Osterns) are filmed in Russia. More recently we have the ‘Pavlova Western’ — filmed in Australia or New Zealand e.g. Mike Wallis’ Good for Nothing or John McLean’s Slow West. While these films can still have great storylines, having grown up in New Zealand and emigrated later to Australia, the trees and landscapes look far too familiar to work for me as American stories. Australian locations are also known as Meat-Pie Westerns.

You can probably guess what Curry Westerns and Indo Westerns are.

Westerns set and filmed within America itself are even broken into subcategories. Take Florida Westerns, also known as Cracker Westerns, set in Florida during the Second Seminole War.

Characters Of Westerns

A character in a New York novel might look at the city, the press of diverse humanity, the huge buildings, the hum of activity, and feel that his/her life is insignificant or at the very least, a exceedingly small cog in the greater machine of human endeavors.

A character in a Western novel looks out at a terrifyingly empty prairie, an expanse of jagged mountains, the infinite wash of stars in an unpolluted night sky, and feels not so much that his/her life is insignificant but that humanity as a whole has vastly overestimated its own importance to the universe.

The characters in a Western are fairly regular forced to acknowledge the real scale of the world and their place in the cosmos, and I find that refreshing.

Callan Wink, Publishers Weekly

Problems With The Western

Reading Against Genre: Contemporary Westerns and the Problem of White Manhood by Donika DeShawn Ross (2013)

Examples Of Anti-Westerns

- Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

- The Wild Bunch — set in the last days of the American Frontier. In both Butch Cassidy and The Wild Bunch (about the same real-life group of outlaws) the characters aren’t keen on new technologies. Butch Cassidy and the townspeople want nothing to do with the bicycle, for instance.

- Is Lonesome Dove an anti-Western? Before its publication in 1985, McMurtry was known as a contemporary novelist who made a point of denouncing unrealistic, romantic period novels about the frontier. The old myths were destructive, he argued, and they ignored the complex, urbanized realities of the modern West. Then he wrote “Lonesome Dove,” an 843-page frontier epic that seemed to be exactly the sort of book he had been attacking. […] McMurtry thought he had written an anti-Western, one that critics and readers then perversely took to be the greatest Western ever. “‘Lonesome Dove’ was a critical book,” he still insists, “but that’s not how it was perceived. The romance of the West is so powerful, you can’t really swim against the current. Whatever truth about the West is printed, the legend is always more potent.“

- His response to the misreading of “Lonesome Dove” was “Streets of Laredo,” which takes place 20 years later, and “Comanche Moon,” which deals with the same characters as young men. In both books (as well as in “Dead Man’s Walk,” the prologue to the series) he tried everything possible to destroy the romantic aura of the original novel. Where “Lonesome Dove” was heroic and sweeping, the subsequent books are bleak and austere. And “Streets of Laredo,” written during the long siege on that couch in Tucson, is the darkest of them all.

- Woodrow Call, who survived “Lonesome Dove” intact, is shot several times in “Streets,” finally losing his arm and leg. “He would have to live, but without himself,” McMurtry wrote of his shattered hero. “He felt he had left himself faraway, back down the weeks, in the spot west of Fort Stockton where he had been wounded. … He could remember the person he had been, but he could not become that person again.“

- Hud — McMurtry’s first book, published as Horseman, Pass By is often listed as a Western, or rather the first of the ‘revisionist Westerns’. I’m not sure how Larry McMurtry feels about it, but the screenwriters consider this story a domestic drama.

- The Homesman — published a few years after Lonesome Dove in 1988, and made into a film by Tommy Lee Jones in 2014. This is such a harsh story it would be hard for audiences to mistake it for a love-letter to the Old West.

- The work of Annie Proulx is unambiguously anti-Western (if we’re calling it Western at all). In her Wyoming Stories she offers a searing critique of cowboy culture and satirises the mindset that Wild West culture is some kind of aspirational ideal. Brokeback Mountain is the most famous of these. However, Annie Proulx would not call this story any kind of Western (or a romance). It is the exposure of a community with rot and hatred at its core.

- Richard Ford is another author who, early in his career, released a short story collection set in Wyoming and Montana, frequently described as ‘hardscrabble’. The collection is called Rock Springs.

- Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson — Set in the haunting rain-soaked Northwest, Robinson’s characters are dogged by loss, encroaching transience and the siren call of the cold mountain lake that exists at the centre of the narrative.

- Cowboys and East Indians by Nina McConigley —McConigley’s stories explore what exactly it means to be the “wrong kind of Indian” in Wyoming. These characters subvert our expectations and give us a new way to look at place, even one as saturated with myth as the American West. Funny, poignant, and incredibly smart.

- True Grit — the movie and the Coen Brothers remake

- The Son by Philipp Meyer

- Legends of the Fall by Jim Harrison

- Winter in the Blood by James Welch

- The Proposition — Australia’s version of an anti-Western

- The Englishman’s Boy — a Canadian example

- The Misfits

- Sin Nombre

- Lonely Are The Brave

- The Rounders

- The Reward

- Moon Zero Two

- The Traveling Executioner

- Deadlock

- The Resurrection of Broncho Billy

- Angels: Hard as They Come

- The Day of the Wolves

- Squares

- Pocket Money

- Longmire — is often marketed as a neo-Western but it is more of an anti-Western. Walt Longmire is the dedicated and unflappable sheriff of Absaroka County, Wyoming. Widowed only a year, he is a man in psychic repair but buries his pain behind his brave face, unassuming grin and dry wit. He is an anti-hero.

- Justified — another TV series set in the West

- Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee

- Meek’s Cutoff — cinema verite, which means it’s like the camera isn’t there. Also means it doesn’t hew closely to dramatic structure, most apparent in the ending of this film.

- They Die By Dawn

- Hell Or High Water — Before 2016 inflicted itself upon us, screenwriter Taylor Sheridan pre-empted the election results with Hell or High Water, a neo-Western with anti-capitalist undertones. With banks ripping off policemen and robbers alike, and its politically charged juxtapositional images of oil wells towering over foreclosed homes, the film tapped into an Occupy-inspired sense of moral outrage at corporate tyranny shared by both rural and urban Americans alike.

- Wind River — Sheridan’s film touches on the intrusion and violation of the reservation land on which it’s set by encroaching oil giants and their employees.

- etc.

Examples of Neo-Westerns

- Kill Bill Vol. 2 directed by Quentin Tarantino — another good versus evil story but with an almost futuristic Japanese setting

- Mad Max — sometimes called a ‘road Western’. Australian Westerns like this dystopian franchise can be viewed as cautionary tales on resource greed: when oil (or “guzzolene”) runs out, the films tell us, nuclear war and a kill-to-survive mentality will plague the earth, decimating populations and sharply cleaving society into the exploited many and the soul-sucking, resource-hoarding few.

- The Proposition — Australian

- The Rover — Another Australian film

- Serenity — 2005, based on the Firefly TV series

- Star Trek — Famously Gene Roddenberry pitched the concept of the TV show Star Trek as a Wagon Train to the stars

FURTHER READING

7 Historical Fiction Novels Set in the Pacific Northwest at Electric Lit

SPECULATIVE WESTS: Popular Representations of a Region and Genre by michael k. johnson

The Western as a genre is alive and vibrant, argues University of Maine – Farmington professor of English literature Michael K. Johnson. In Speculative Wests: Popular Representations of a Region and a Genre (U Nebraska Press, 2023), Johnson explains how authors, directors, and storytellers are pushing the classic genre into new directions by hybridizing Western tropes with science fiction, horror, and fantasy storytelling. These new speculative Westerns are revitalizing a genre, which has grown incredibly popular in recent years through television series like The Last of Us and Westworld, as well as many examples in film and literature. Speculative Westerns have also allowed space for Native and African American writers and storytellers to expand the genre into more inclusive spaces, telling stories about people often left out or stereotyped in more traditional Western stories. By including time travel, zombies, and vampires, Johnson argues that the Western has cemented itself with a new generation of Americans as one of the critical cultural narratives for understanding the United States.

interview at New Books Network

The Westerns and War Films of John Ford

While John Ford made films of more general subjects, he is best known for his movies that illustrated the American West and life during wartime. In her book, The Westerns and War Films of John Ford, Sue Matheson examines what was so special about his works, as well as how his films represented Ford’s view of America.

New Books Network

PEACE AND FRIENDSHIP: AN ALTERNATIVE HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN WEST

The history of the American West has typically been told in one of two ways: as triumph, or as tragedy. Stephen Aron, accomplished scholar of the West, Professor Emeritus at UCLA, and President of the Autry Museum of the American West, argues that both of these narratives flatten out what was actually a much more complicated story.

Peace and Friendship: An Alternative History of the American West (Oxford UP, 2022), Aron zooms in on several moments of contingency in the Western past, moments when people of often radically different backgrounds came together to build community, or at least lived peacefully, despite their differences. Although these moments eventually fell apart, Aron argues that they show that the past was unwritten until it came to pass, and that our own uncertain future is the same. Peace and Friendship offers important lessons about the power of history and contingency, and underscores the unsettled nature of human events and our capacity for overcoming even our deepest differences.

New Books Network