“We Didn’t” is a short story by American writer Stuart Dybek, included in The Best American Short Stories 1994. A man addresses his first love. With the insight that comes from middle-age, the narrator feels sad about the tragicomic incident that that led to their breakup: The young couple were about to have sex when they were interrupted by a circus of cops, who found the floating dead body of a young woman in surf just metres from where they had chosen their spot on the beach.

SYMBOLISM

Stuart Dybek is a master of the symbolic web, or what some people call the imagistic pattern which pulls a literary short story together. In “Pet Milk” he gave us the imagistic pattern of the spiral. Dybek even shapes that story like a spiral.

In “We Didn’t” he presents us with a circle comprising smaller circles, symbolised most clearly by the rosary beads. Also:

- The circle of life, in which the young dead pregnant woman brings youth, birth and death together in one very ‘uncomfortable’ scene.

- The circular coast of the lake (as opposed to an ocean beach)

- The two teenagers sitting on the beach, so close to the cops that they form a part of their circle, like beads in their own messed up rosary

- At a structural level, the narrator circles back to his youth in the retelling of this story, addressing someone important from his past.

PARATEXT OF “WE DIDN’T”

From the title, Dybek dilates the pacing by describing what does not happen. It may seem unintuitive to try to draw readers in by saying what is not, but we trust that the not will lead into something that is.

This way of writing mimics the far more common switch from iterative to singulative time that we see in different kinds of stories, especially obvious in children’s picture books (because picture books are so short): “Every morning, Johnny would X, Y, Z. But ONE DAY…”)

SETTING OF “WE DIDN’T”

Dilated pacing affords the writer time to insert detail, and that’s what Dybek does here, painting the setting in a single paragraph of what, ostensibly, ‘did not’ happen:

We didn’t in the light; we didn’t in darkness. We didn’t in the fresh-cut summer grass or in the mounds of autumn leaves or on the snow where moonlight threw down our shadows. We didn’t in your room on the canopy bed you slept in, the bed you’d slept in as a child, or in the back seat of my father’s rusted Rambler which smelled of the smoked chubs and kielbasa that he delivered on weekends from my Uncle Vincent’s meat market. We didn’t in your mother’s Buick Eight were a rosary twined the rearview mirror like a beaded black snake with silver, cruciform fangs.

Opening paragraph of “We Didn’t” by Stuart Dybek

Already we know that this story is circular. ‘We didn’t in the light; we didn’t darkness’ feels like a riff on Genesis… “And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night, and there was evening and there was morning, the first day…” The sentence structure feels as if someone slows down for a prayer, and that is what prayer is; during prayer, ideally the pace of life dilates to a standstill.

Stories which feature the seasons, especially the four seasons we associate with Western culture, indicate circularity. Dybek takes singular details from each season, the fresh-cut summer grass, the leaves of autumn, the snow of winter. (Interesting that he leaves out specific mention of spring. Perhaps because these young people are in the symbolic spring of their lives.)

Next, in a single sentence, Dybek takes us through childhood using beds as metonym. The bed of early childhood, the bed of middle childhood, and now the sexually charged ‘rusted Rambler’ of young adulthood, where the narrator had hoped sex would play out. (The ‘meat market’ is a darkly comical touch.)

Finally, Dybek invites us into his symbol web of circles, each almost touching but not quite, by mentioning the rosary beads.

By associating the rosary beads with his girlfriend’s mother and the rusted Buick (more suited to sex) with the narrator’s father, Dybek is also setting us up for a story which explores gender differences.

Notably, that fertile people with wombs, mostly women, have a different experience with sex, especially in the period this story is set. This is a man looking back from middle-age, to a time of drive-in theatres, when Doris Day was in her heyday. This is a story set in the 1960s, before the proliferation of birth control, and when young Catholic women might still be ostracised and abused if they became pregnant before marriage. They lived under the spectre of Magdalene Asylums. Many others were expected to marry the man who got them pregnant. Sex was literally dangerous to women. This short story takes that fear and channels it through a scary scene.

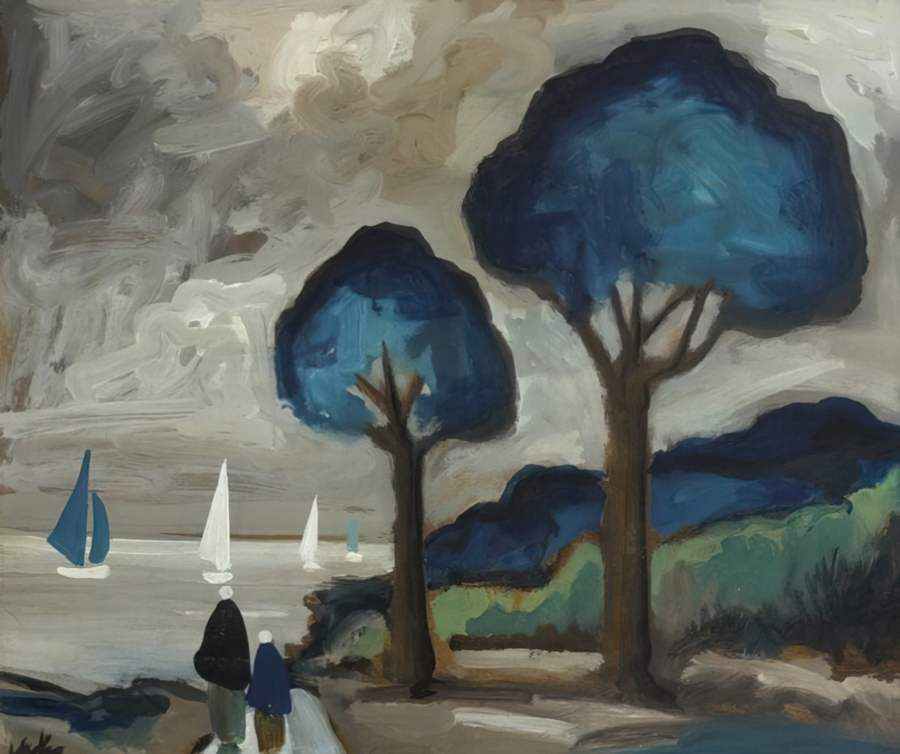

Where is this beach? Like most Australians, when I think Gold Coast I think of Queensland. Now I know there’s a Gold Coast in Chicago, Illinois. In the story, Dybek describes the pink sunset which changes into something darker, prefiguring the girlfriend’s change of heart:

The lake had turned hot pink, rose rapture, pearl amethyst with dusk, then washed in night black with a ruff of silver foam.

“We Didn’t” by Stuart Dybek

STORY STRUCTURE OF “WE DIDN’T”

SHORTCOMING

The extradiegetic first person narrator looks back from middle age on his horny youth. He is impatient and insufficiently attuned to the different sexual experience of his young girlfriend.

In the story, the narrator thinks sex is going to resemble the scripted and acted versions of sex he’s seen out of Hollywood. He mentions the famous beach scene from From Here To Eternity. (Looking at it now, I’m pretty sure the girl who gets munched at the start of Jaws was also trying to emulate this scene, running off down the beach hoping the boy will follow her.) Ironically, in the movie, Deborah Kerr’s character confesses to Burt Lancaster’s character that she can’t ever have children. Ironic because the prospect of pregnancy is the very thing that terrifies the narrator’s young girlfriend.

DESIRE

He is desperate to have penetrative sex with his Catholic girlfriend.

OPPONENT

Everything in their life conspires to not let this happen.

PLAN

The narrator has been carrying a condom around for ages, waiting for the right moment. Finally they are alone on the lake beach one night and it almost happens. He gets so far as fumbling with the rubber.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

But then the cops show up.

I was trying to calm your terror with reassuring phrase such as, “Holy shit! I don’t fucking believe this!”

“We Didn’t” by Stuart Dybek

The dead body feels to the girlfriend like a bad sign.

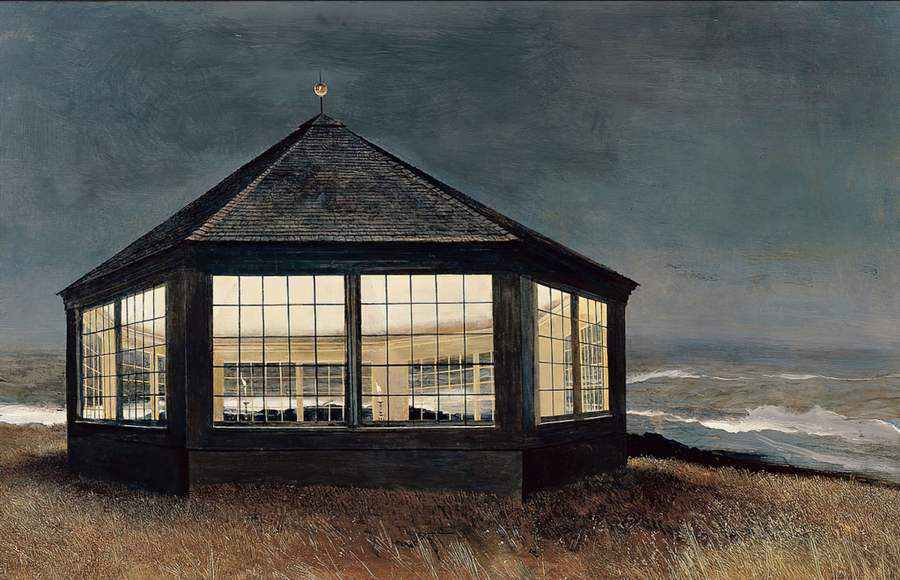

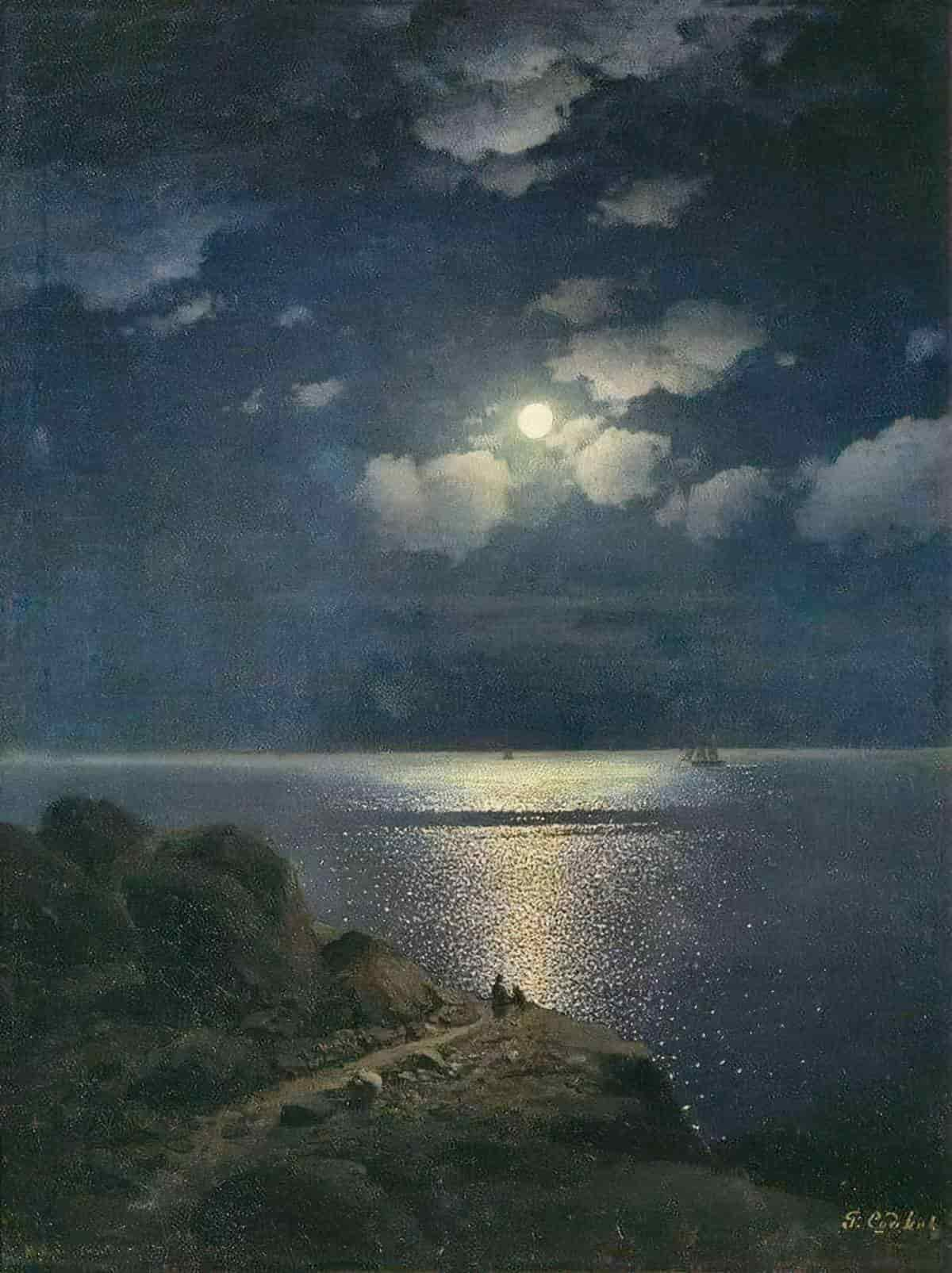

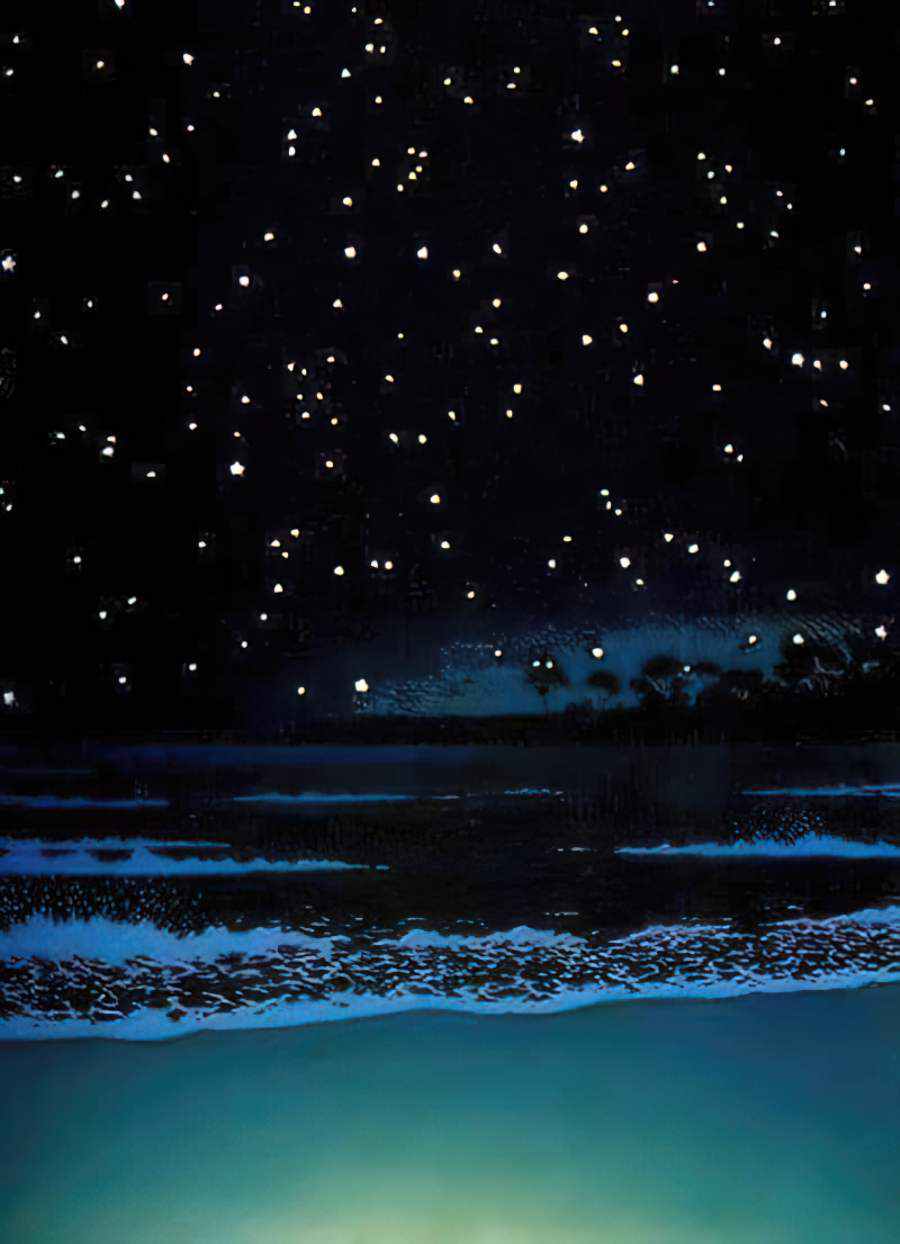

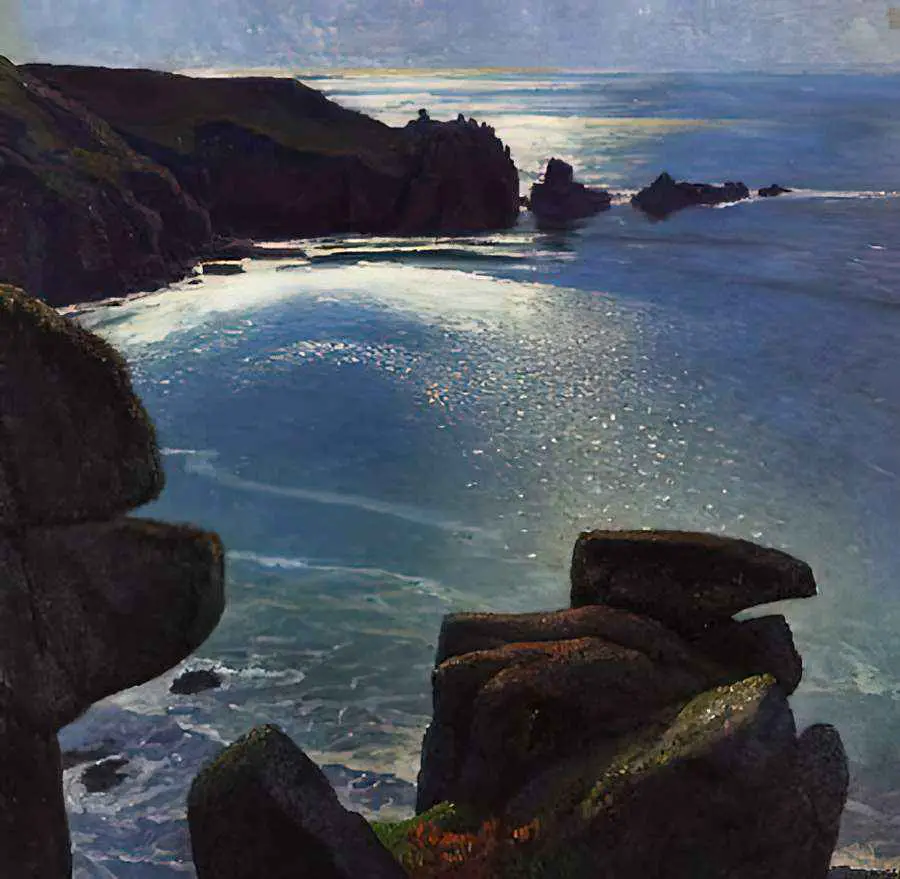

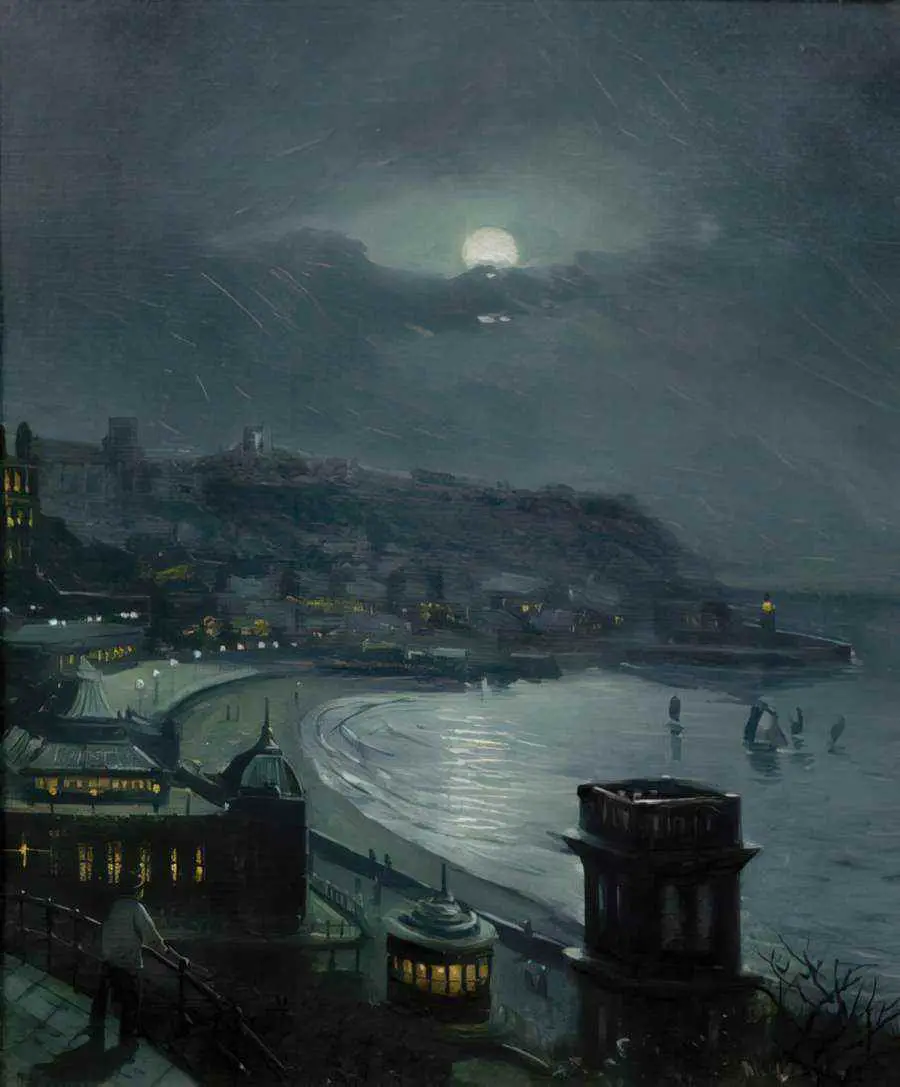

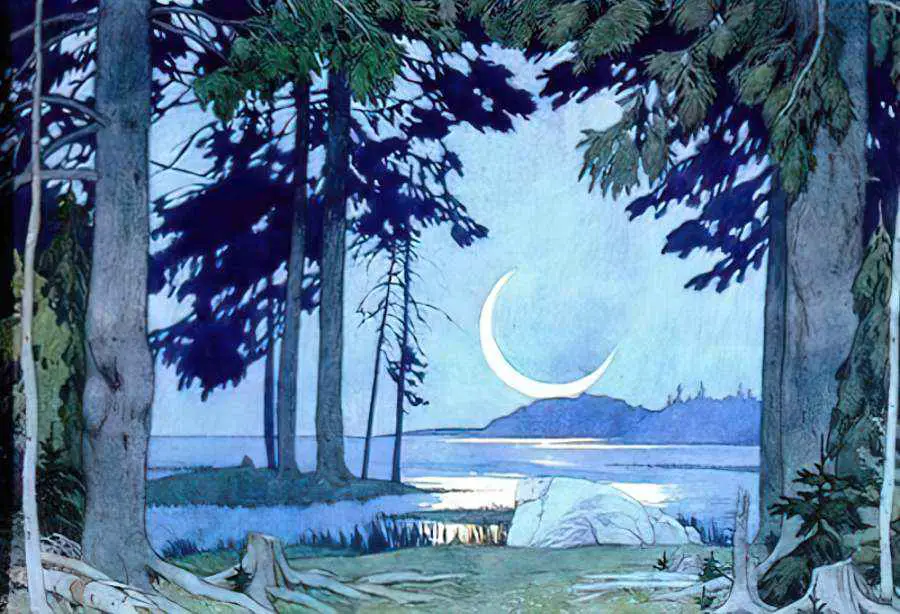

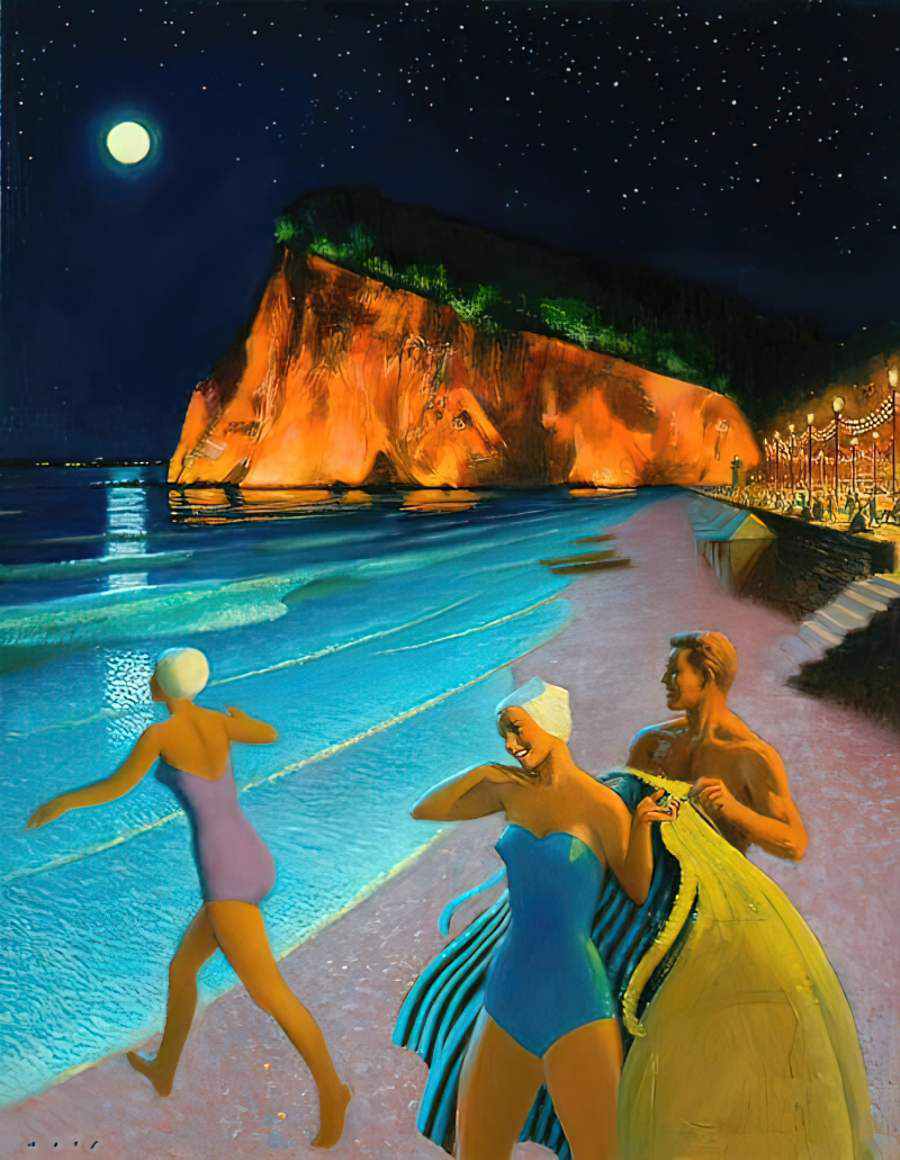

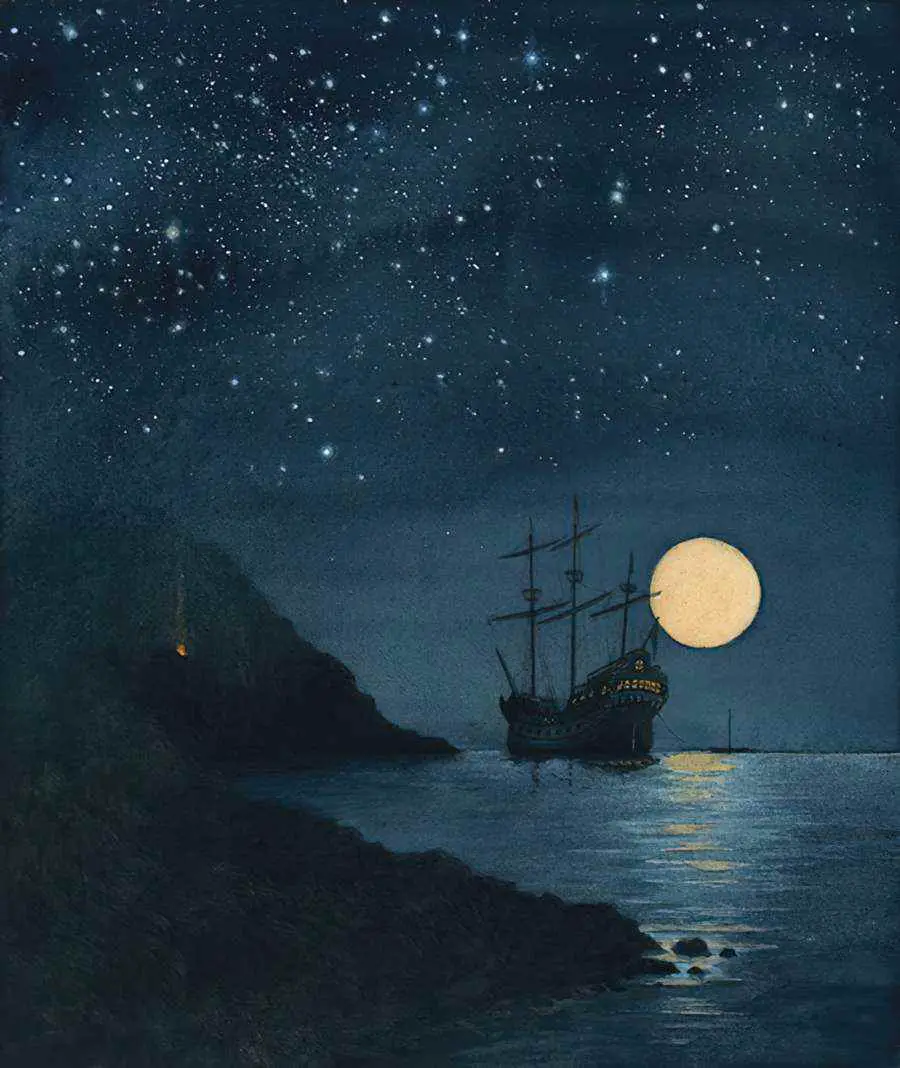

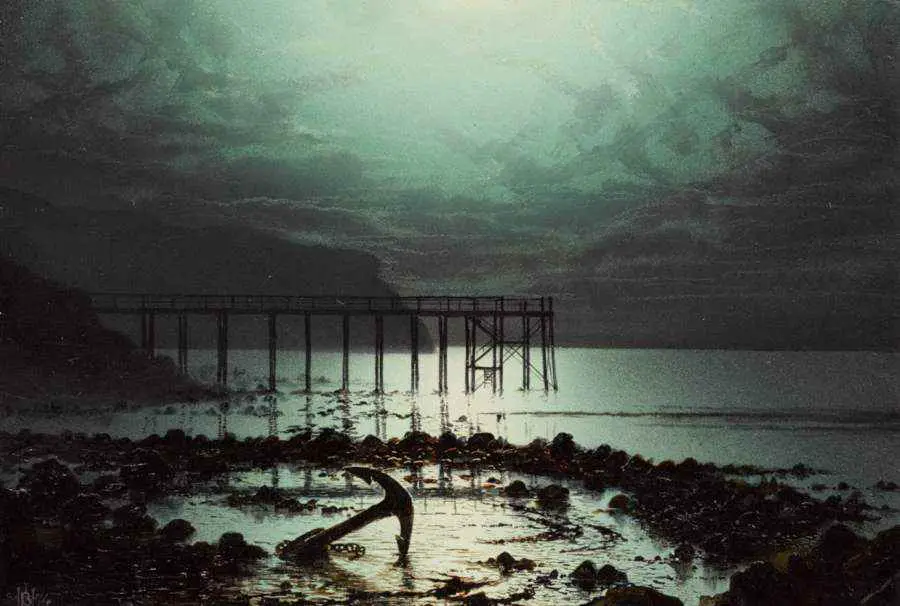

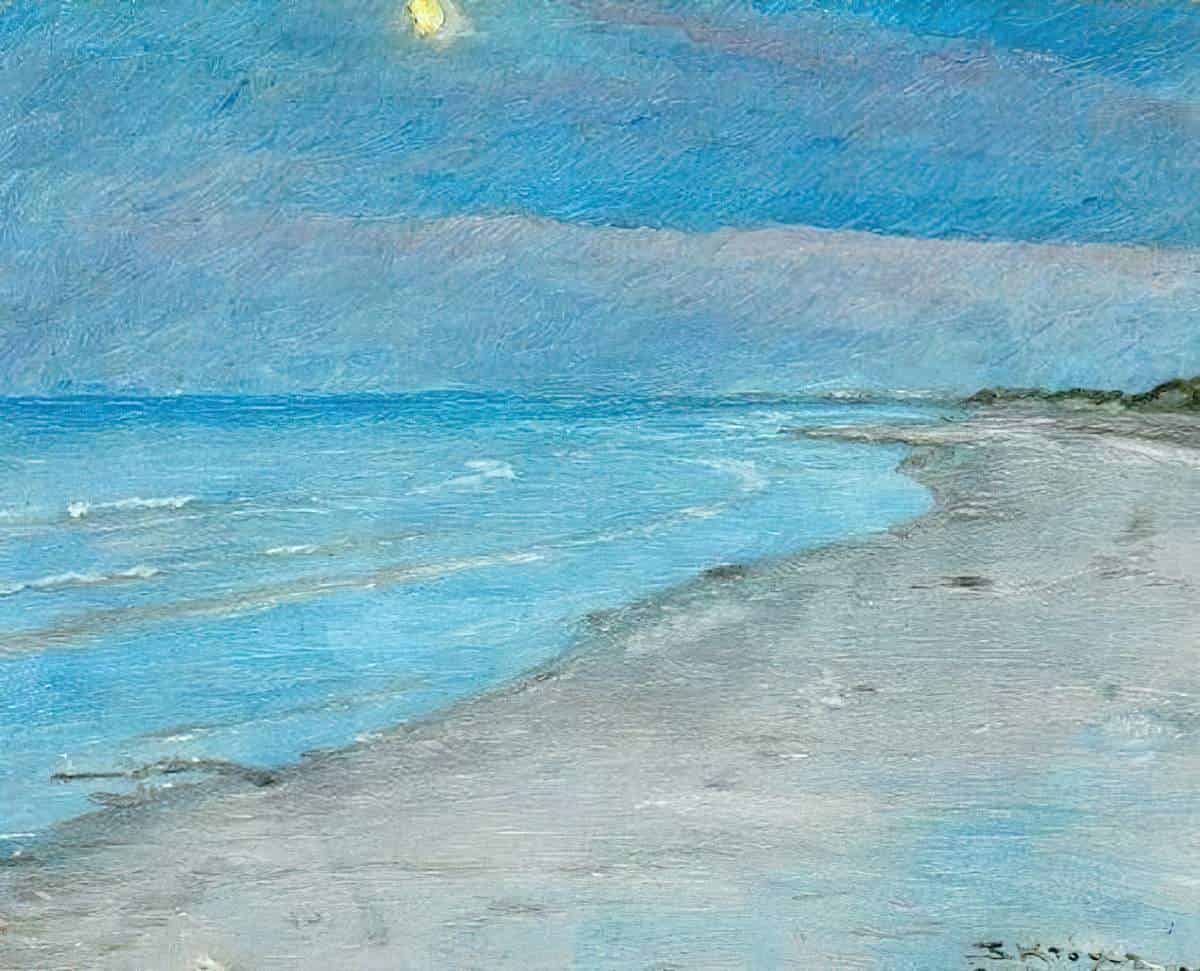

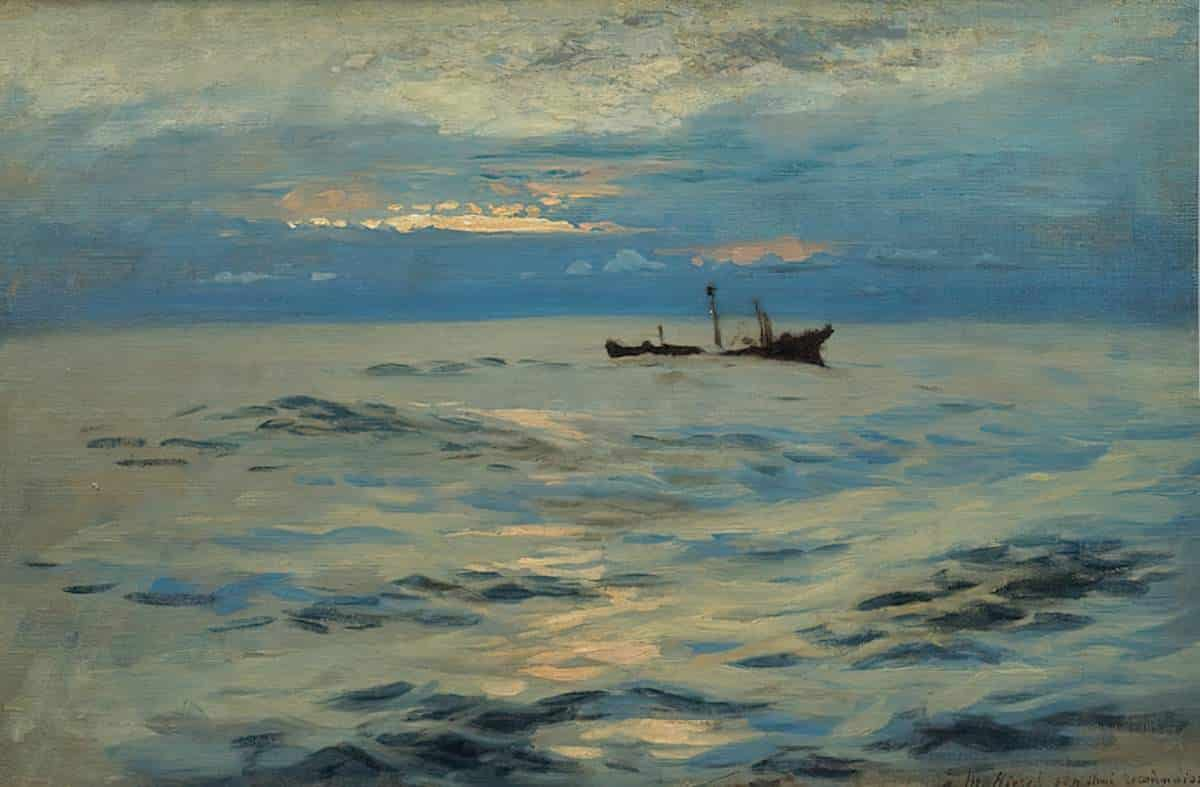

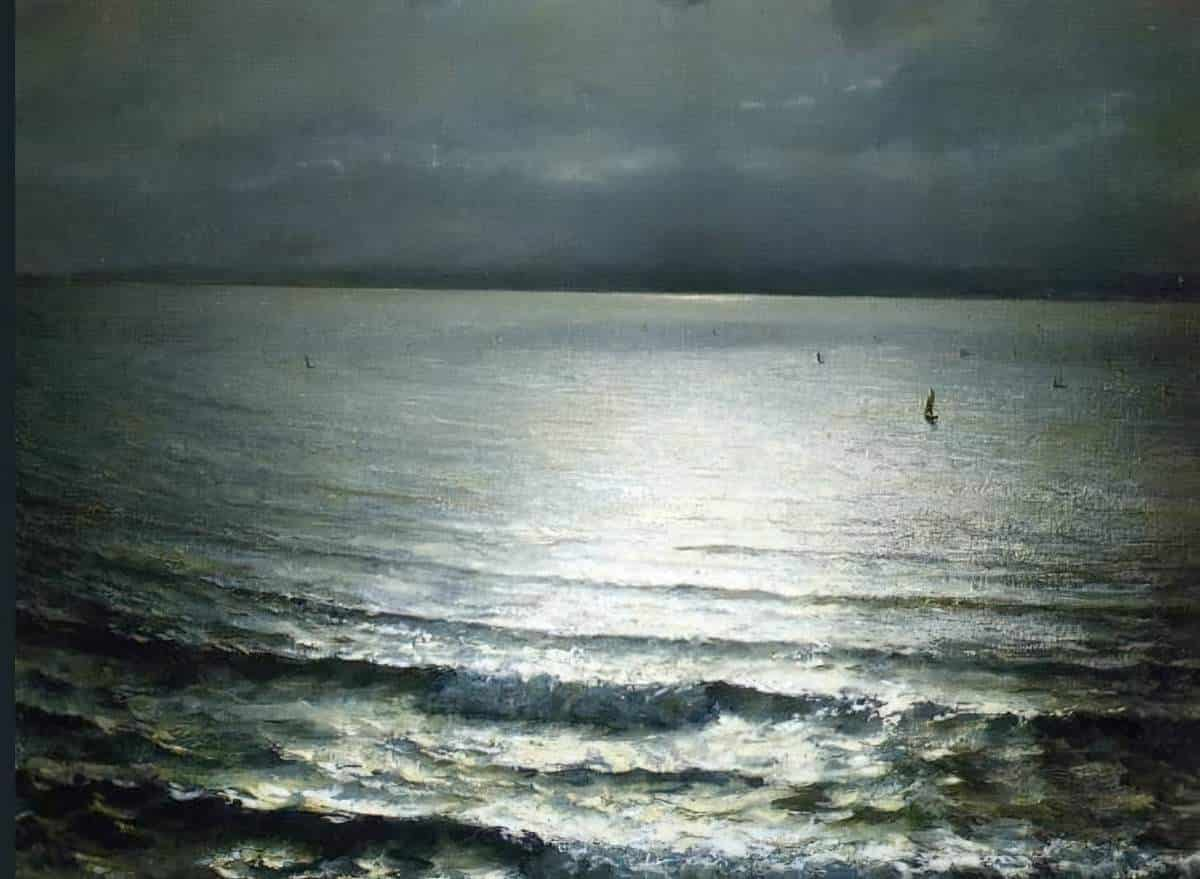

Let’s take a moment to admire paintings of beaches at night, and talk about the climactic scene of “We Didn’t”, which is a fluid, malleable and multi-layered space, completely typical of liminal spaces. The night beach has two layers of liminality to it: The beach marks the boundary between sea and land. The dark of late evening marks the boundary between night and day.

THE NIGHT BEACH AS LIMINAL SPACE

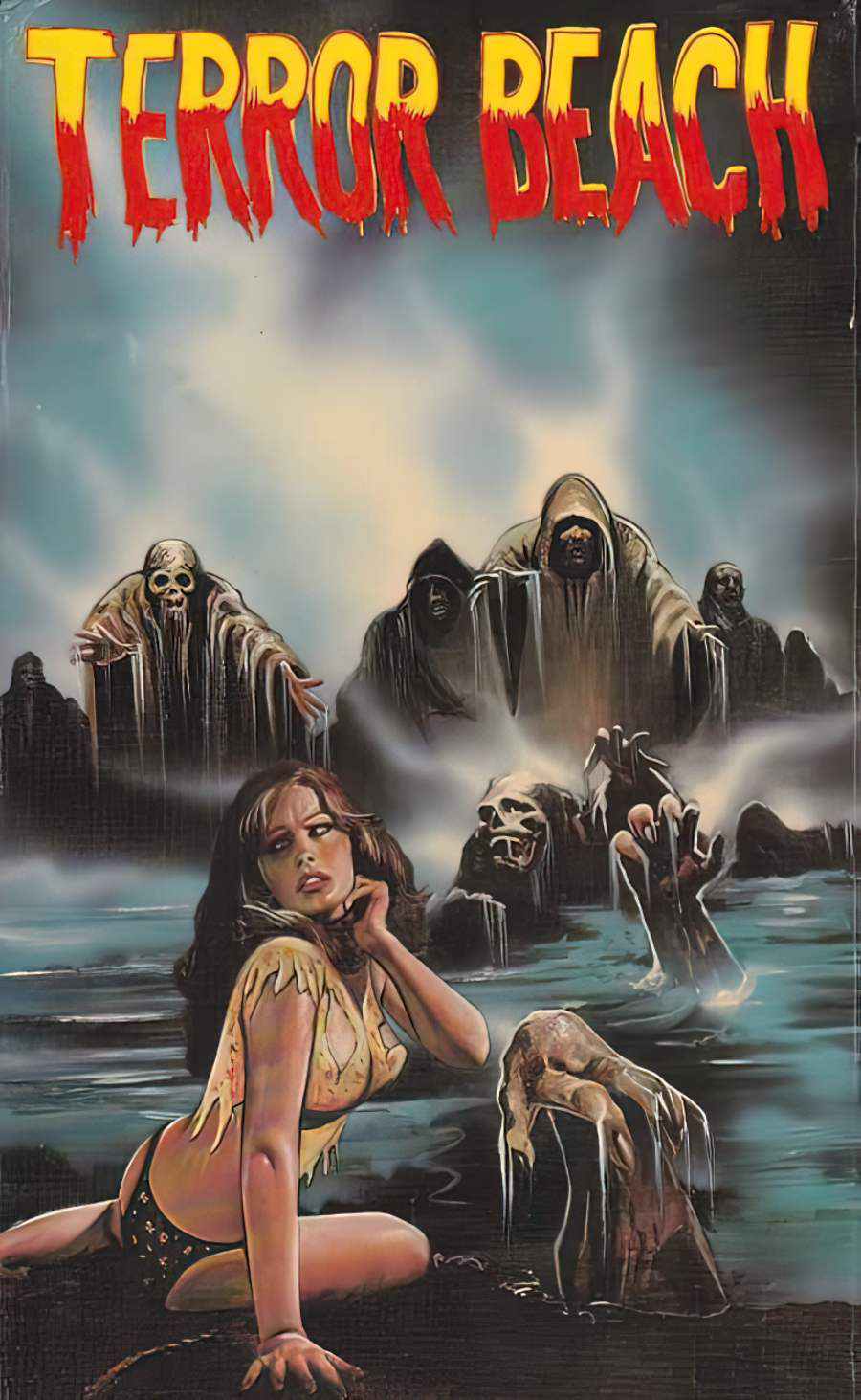

The beach during daytime is mostly a fun experience: sandcastles, surf, sand in your sandwiches. Beach cricket, volleyball, fun with friends and family. Occasionally, storytellers take the happy beach and invert it for Gothic purposes.

But return to the same beach at night and you have something completely different. The beach at night requires no Gothic inversion. Under a cloak of darkness, the moonlit shoreline is now ethereal and spooky.

Why does one feel so different at night? Why is it so exciting to be awake when everybody else is asleep? Late—it is very late! And yet every moment you feel more and more wakeful, as though you were slowly, almost with every breath, waking up into a new, wonderful, far more thrilling and exciting world than the daylight one. And what is this queer sensation that you’re a conspirator? Lightly, stealthily you move about your room. You take something off the dressing-table and put it down again without a sound. And everything, even the bedpost, knows you, responds, shares your secret…

You’re not very fond of your room by day. You never think about it. You’re in and out, the door opens and slams, the cupboard creaks. You sit down on the side of your bed, change your shoes and dash out again. A dive down to the glass, two pins in your hair, powder your nose and off again. But now–it’s suddenly dear to you. It’s a darling little funny room. It’s yours. Oh, what a joy it is to own things! Mine–my own!”

Katherine Mansfield, “At the Bay“

ANAGNORISIS

“She was pregnant,” you said. “I mean I don’t want to sound morbid, but I can’t help thinking how the whole time we were, we almost — you know — there was this poor dead woman and her unborn child washing in and out behind us.”

“We Didn’t” by Stuart Dybek

The young narrator experiences no understanding of his girlfriend’s change of heart, not at the time. It is only in hindsight and with longing reflection that he is able to slow down and circle back to why she may have felt as she did. At the time, he applied misplaced rationality to the situation, telling Jules that they didn’t find the body, that they didn’t know the woman who died. (Note how the title becomes multilayered at this point.)

But for Jules, these ‘did nots’ are irrelevant, because the incident continues to haunt her in her dreams. Pregnancy is terrifying. Pregnant bodies are terrifying. People forget this now, and I’m not sure young cis men have ever, en masse, understood the extent of it.

We know the narrator has since developed a modicum of insight because he is writing from a detached point of view, describing his young self almost as a separate person entirely. He is able to laugh at himself. He is able to admit when he said one thing but thought another. He can see that his sex jokes are off-colour and insensitive. He can see where conversations went off the rails.

Even if the adult narrator is unable to see everything as connected, Dybek’s symbol web helps the reader to.

Dybek does something else masterful at this point, which propels this short story into the stratosphere. He gives Jules depth by writing this:

“It’s sad,” I started to say, meaning that I was sorry we had reached a point of sitting silently together, but before I could continue, you challenged the statement.

“We Didn’t” by Stuart Dybek

“What makes you so sure it’s sad?”

“What do you mean, what makes me so sure?” I asked, confused by your question, and surprised there could be anything to argue over no matter what you thought I was talking about.

You looked at me as if what was sad was that I would never understand. “For all either one of us knows,” you said, “she could have been triumphant!”

In an attempt to understand, the narrator goes into his Jungian subconscious (by riding the underground) during a storm, but the ‘lights flicker’, meaning he will have only a faulty, partial, incomplete anagnorisis. To really understand what his girlfriend said, he’ll have to wait decades.

So what do you think the girlfriend meant by that?

Well first, tragi-comically, Dybek suggests Jules has been reading Sylvia Plath. So Jules may be romanticising poetic, beautiful young women who end their own lives prematurely. She sounds as if she’s is immersing herself fully in the 1960s Gothic tradition.

More than that, she is pointing out to her boyfriend, who she now understands to be on a completely different wavelength, that he doesn’t actually know what goes on in the minds of other people, specifically the minds of young women. He is too far removed from the terrors and consequences of sex to understand the possible symbolism of the floating dead body right where you were about to have baby-making sex for the first time. He doesn’t know what the dead girl was thinking, and he doesn’t know what this live girl is thinking, either. He doesn’t have sufficient empathy or life experience. Horniness overwhelms him. He even leaves his dropped daks in a puddle, hoping Jules will find them. Instead of experiencing that epiphany on the subway, he comes up with the name “Blue Ball Express”. He’s been hijacked by his hormones, and it’s all about him.

However, he does come close to an experience which almost mirrors the experience of his girlfriend, seeing the pregnant + dead + young + girl in the water. He sees different versions of himself, each at a different stage of his and Jules’ physical relationship. I say almost mirrors, but not really. This imagery underscores his horny self-absorption, whereas Jules has been propelled out of herself, out of the moment, by something far bigger than herself: The power and the terror of possibly creating new life.

NEW SITUATION

The dead body has brought the fear of sex (and pregnancy, and spiritual death) into sharp focus for the girlfriend. They now argue about sex as the narrator continues to pressure her, demanding reasons why they can’t try again.

This pressure impacts the rest of their relationship, until they argue about everything all the time, then eventually part ways.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

I suspect this story will be read differently in the post #MeToo era, because this story changes from one of enthusiastic experimentation into one of coercion. Before they are interrupted, enthusiastic consent is clearly given, “Oh Christ yes“. Followed by “Yes wait… Stop!“

I don’t see evidence that the adult narrator regrets his own part in coercion; rather, he looks back and regrets the situation.

RESONANCE

Stories which fold death and sex into each other proliferate. Moralistic stories are so common, they work well when subverted for comedic effect:

Mrs. Weir: Alright, kids. High school is for learning but it’s also where you should be learning to socialize. That’s what high school dances are all about.

Freaks and Geeks

Lindsay: No they’re not. It’s a chance for popular kids to experiment with sex in their cars.

Mrs. Weir: Lindsay!

Mr. Weir: Hey!

Lindsay: I mean, if that’s what you want me to do then I’d be happy to go.

Mr. Weir: You know, there was a girl in our school, she had premarital sex. You know what she did on graduation day? Died! Of an overdose. Heroin.

Stories with the specific function of scaring young people (especially young women and LGBTQ+ youngsters) away from sex frequently find a natural home in urban legend. Take “The Hook” as a classic example of that: A young woman goes with her boyfriend to make out in their car when they hear an ominous sound on the roof. The young man valiantly goes to investigate but never comes back. Eventually police turn up and tell the young woman not to look back. She does. She sees a murderer on the car roof, holding the head of her boyfriend. The moral: Don’t have sex. Sex will lead to death.

Like Freaks and Geeks does in comedic form, Stuart Dybek avoids the didactic and subverts the ‘don’t have sex’ message by looking back with huge regret at what never happened. Now the narrator can only circle back in his memory and imagination to what might have been.