EPISODE ONE, PART ONE

John Berger tells us that late 20th century audiences view classic paintings very differently from earlier people.

A large part of seeing depends on habit and convention. European paintings are made for European perspectives. Perspective depends on the eye of the beholder, like an inverse lighthouse. Instead of light beaming in, the image beams in.

These appearances are called ‘reality’. But the human eye can only be in one place at the one time. The invention of the camera (the ‘mechanical eye’) changed all that. Appearances could now travel across the world.

The invention of the camera changed not only what we see but how we see it. The camera even changed paintings long before it was invented. Like the human eye, a painting on the wall can only be in one place at one time. The camera reproduces it, making it available in any size, anywhere, for any purpose.

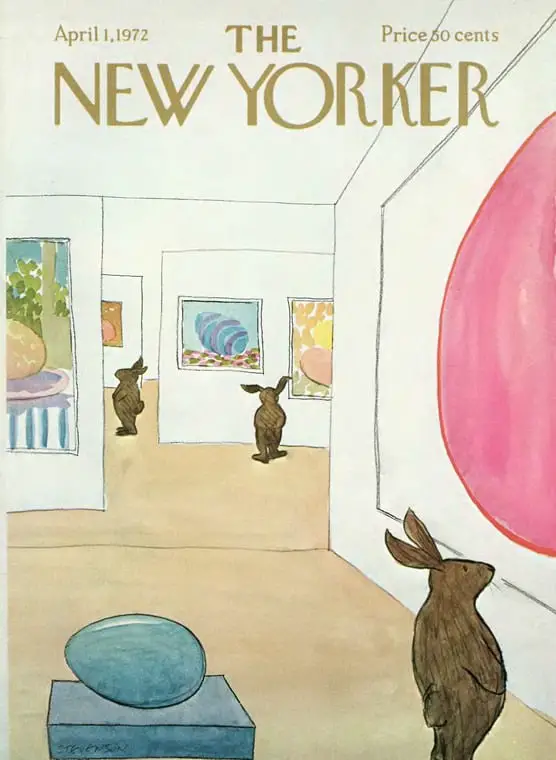

Now these reproductions are in your own environment, you’re seeing them within a familiar context. Originally, paintings were an integral part of the building for which they were designed, making up the building’s ‘memory’, part of its individuality. Everything around the image was part of its meaning, and its uniqueness as unique as the building housing it.

A religious icon used to be a part of the church, and you’d have to go on a pilgrimage to see it. Now you can own this iconography in your own home. Its meaning, or a large part of it, has become transmittable. It comes to you, like the news of an events, a type of information.

EPISODE ONE, PART TWO

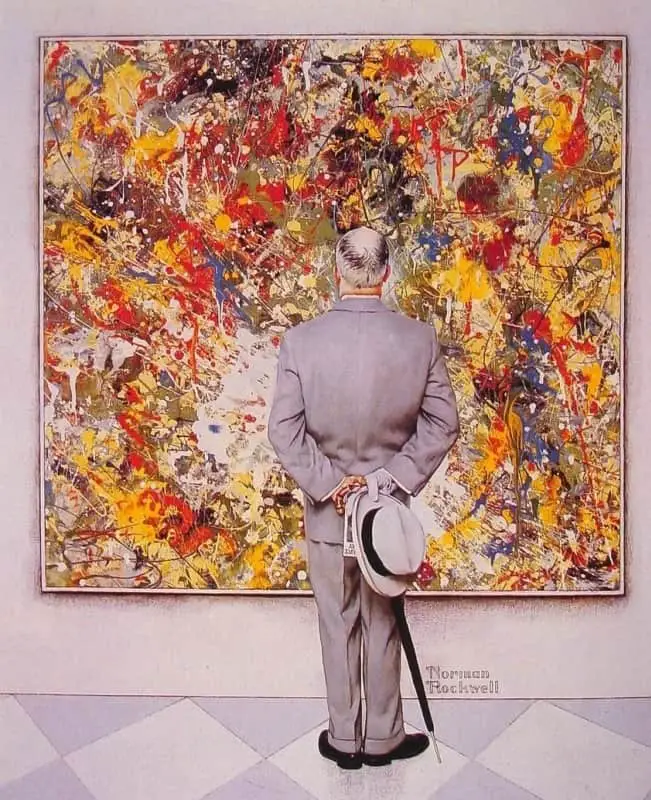

Original paintings are still unique. They look different from the reproductions, which distort. When looking at an original we should be able to feel some sense of its originality.

In this way, art encourages certain expectations. Sometimes an image becomes mysterious because of its market value, which depends upon its being genuine, not necessarily because of what it depicts.

Sometimes we feel awe in front of a painting because it has survived, or because it has a certain value, a certain fame, and that is why we are feeling what we are feeling.

This cash value is a kind of religiosity, a substitute for what paintings lost when the camera made them reproducible. The camera has multiplied a painting’s meanings while at the same time destroying its original meaning.

Have works of art gained anything by this? They have both lost and gained:

The most important aspects of paintings: they are both silent and still. Occasionally, this uninterrupted silence and stillness can be very striking. The experience of this has hardly anything to do with what teachers say about art.

Paintings lend themselves to easy manipulation with many different meanings. Movement and sound are the best way to manipulate meanings, for instance a camera zooms in to remove a detail of the painting from its whole. The meaning of a painting shown on film/TV can be presented even more differently. An entire picture is always quite different from a detail of it. On a screen it’s impossible to view an entire painting because details are lost.

[Big screen modern TVs do in fact make that possible but aren’t very often used in that way, except for Smart TVs, before you crank up the program you sat down to watch, and you’re watching classic paintings while you wait.]

EPISODE ONE, PART THREE

The pan and the zoom can work together to offer the story of a painting, but in a film sequence the details have to be rearranged in a way that represents unfolding time. Yet in the painting as a whole, all these elements are there simultaneously. In paintings there is no unfolding time.

[Time sequences can however be suggested, even in a static image. See my posts on narrative art, for example this one.]

Paintings are also changed by the sounds you hear when looking at them. Voice over changes your perception of a static image. Music is more subtle — we often don’t even notice it, yet it changes the emotions we experience while viewing.

Paintings can also changed in another way. They often appear alongside words, competing for attention. The meaning of a painting can be changed depending on what appears around it, what you saw right before it, what you’ll see right after.

Images can be used like words — we can talk with them. Reproduction makes it easy to connect our experience of art with other experiences. This isn’t sinister, so long as we know that’s what’s happening.

Moreover, the false mystification around art keeps art within the narrow preserves of the art expert. [Art has historically been regarded as ‘mysterious’, one of the three epistemological categories proposed by historian Jill Lepore.]

EPISODE ONE, PART FOUR

Art experts even write detailed art books which nevertheless distance the ‘ordinary’ viewer from the artwork. This is mystification. Children interpret images very directly, linking it to their own experience, until they are taught not to trust their own responses over that of ‘experts’.

Children recognise things in paintings that adults sometimes don’t. In Berger’s example, children point out a ‘sexual ambivalence’ which audiences [of the time] would avoid.