This month I wrote a post on Teaching Kids How To Structure A Story. Today I continue with a selection of mentor texts to help kids see how it works. So far I’ve analysed picture books. Today I analyse a song using the same story template, which happens to be Australia’s unofficial national anthem. I own “Waltzing Matilda” in picture book form, though it always scared me as a kid. Although the tune is upbeat, inspired indirectly by Celtic folk music, “Waltzing Matilda” is a tragic ghost story about theft, suicide and power.

It’s important to understand how valuable sheep have been to Australia’s history.

The first sheep were brought into Australia as mobile meat, mutton for hungry soldiers and convicts. The few settlers who thought of raising sheep for wool had to spend much time and money before their flocks produced fleeces worth the effort. Every fine-woolled sheep imported into the colony had to make a long journey by sea. In 1825 the Riley family imported 200 fine-woolled Saxon sheep into New South Wales. Each sheep cost the same as a year’s wage for a labouring man in the colony. Their transport to Australia cost just as much again.

The Ashton Scholastic History of Australia, Manning Clark, Meredith Hooper, Susanne Ferrier

Banjo Paterson wrote the lyrics to “Waltzing Matilda” in 1895. It’s widely believed the song was inspired by events that happened after The Great Shearer’s Strike of 1891. Why did the shearers strike? Because working conditions were terrible, yet sheep had become indispensable to the wealth of white Australia:

Sheep could be left out in the open all year round in Australia, settlers were discovering, without dying of cold, or heat. Each flock was minded by a shepherd. The sheep must be kept safe from dingoes, who relished this addition to their diet. After sunset the shepherd moved his flock into pens, little fenced-off places in the dark bush. The shepherd’s job was considered ideal for convicts. Working for months in the bush with no companions except greasy sheep and sticky flies was boring and lonely.

The Ashton Scholastic History of Australia, Manning Clark, Meredith Hooper, Susanne Ferrier

Scourgemutton (1581): One who is irrationally cruel (literally a scourger of sheep)

WHAT IS A MATILDA?

The collection of possessions and daily necessaries carried by a person travelling, usually on foot, in the bush; especially the blanket-wrapped roll carried, usually on the back or across the shoulders, by an itinerant worker; a swag. This iconic name for a swag is best know from the title of the song ‘Waltzing Matilda’. The term is a transferred but unexplained use of the female name. Matilda is recorded from the 1880s. For a further discussion of the term and its possible German origins see the article ‘Chasing our Unofficial National Anthem: Who Was Matilda? Why did she Waltz?’ in our newsletter Ozwords.

ANU School of Language, Literature and Linguistics

WHAT IS A BILLABONG?

- Australia: a blind channel leading out from a river.

- a usually dry streambed that is filled seasonally.

- Australia : a backwater forming a stagnant pool.

In this case, we’re talking about a stagnant pool. The associations around billabongs are a bit darker than, say, a swimming hole from other stories and settings. The image below, in contrast, feels cosy rather than ominous.

The billabong which inspired the lyrics is thought to be near Winton, in Queensland. If you go to Winton today you can visit the Waltzing Matilda Centre.

He stopped at a billabong after noticing fish swimming in the middle of the retreating waterway.

“The water had receded and it was down to this dirty water in the middle. I took two steps and the dirty bastard [the crocodile] latched onto my right foot,” he said.

Cattle producer Colin Deveraux survives crocodile attack after biting back

WALTZING MATILDA LYRICS

Once a jolly swagman camped by a billabong

Under the shade of a coolibah tree,

He sang as he watched and waited ’til his billy boiled

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

He sang as he watched and waited ’til his billy boiled,

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

Down came a jumbuck to drink at the billabong,

Up jumped the swagman and grabbed him with glee,

He sang as he shoved that jumbuck in his tucker bag,

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

He sang as he shoved that jumbuck in his tucker bag,

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

Up rode the squatter, mounted on his thoroughbred,

Up rode the troopers, one, two, three,

Whose is the jolly jumbuck you’ve got in your tucker bag?

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me.

Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

Whose is the jolly jumbuck you’ve got in your tucker bag?

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, you scoundrel with me.

Up jumped the swagman and sprang into the billabong,

You’ll never catch me alive, said he,

And his ghost may be heard as you pass by that billabong,

you’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me.

Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

His ghost may be heard as you pass by that billabong,

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me.

Oh, you’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me.

STORY STRUCTURE OF WALTZING MATILDA

Waltzing Matilda is a narrative bush ballad, meaning it’s a complete story set to music.

WHO IS THE MAIN CHARACTER?

A swagman. A man travelling through the Australian bush with a swag (a rolled up bed). An itinerant worker perhaps, between jobs.

What’s wrong with him?

The swagman’s shortcoming is that he’s a farmhand or perhaps a homeless man out of work. He contrasts with the more powerful individuals, who have somehow managed to get their hands on land, using it only to benefit themselves. Most people listening to this song would identify emotionally with the swagman rather than with the aristocracy.

WHAT DOES THE SWAGMAN WANT?

He wants a rest from his travels. He sits down to make himself a cup of tea but he’s also hungry, so he kills a sheep which happens to belong to the wealthy landowner on whose property he squats. Sheep stations in Australia are absolutely massive, so you don’t necessarily know there’s someone on your land.

OPPONENT/MONSTER/BADDIE/ENEMY/FRENEMY

The opponent is the squatter. If this were an English story, he would probably be an aristocratic landowner, but squatter refers to farmers who didn’t necessarily have the papers to properly own their land. The squatter doesn’t want men killing his sheep, which may be his only source of income even if he is wealthy by comparison. Importantly, the sheep may no more belong to the squatter than to the swagman.

WHAT’S THE PLAN?

The swagman’s plan is simple. He will kill a sheep and eat it. The simplicity of his plan is his downfall. He should’ve checked he wasn’t being tailed. (It’s likely he was being tailed, given the vast size of the area, and the low likelihood of randomly being caught.) Many stories include a chase sequence, but the ‘camera’ sticks with the swagman, and the chase is left off the page.

BIG STRUGGLE

Three policemen run after the swagman and apprehend him.

Rather than lose his dignity and his freedom, the swagman dives into the billabong. It’s unclear to me if he meant to suicide with this action — perhaps he hoped to get away somehow. In any case, death is the outcome. (Why? Was it so shallow he suffered a major head injury?)

WHAT DOES THE CHARACTER LEARN?

Main characters don’t learn anything when they are dead at the end. Except occasionally they exist in the spiritual realm. There is an entire subgenre of books narrated by dead main characters, for instance. (The Lovely Bones seems to have started that trend.) Dead narrators seem to suddenly become a lot more emotionally mature, because they’re speaking from beyond the grave and have a more omniscient view of events.

But when main characters die, the reader does learn something. Young child readers learn that stealing can lead to terrible outcomes. Older readers can see that a person without capital can lose everything over very little (a meal), and we learn that some people can gang up on other people without just cause. We learn that life is unfair, basically.

HOW WILL LIFE BE DIFFERENT FROM NOW ON?

In this case, the swagman lives on as a ghost near the billabong. He’s achieved freedom from the law, but now he gets to rest by the same billabong forever. So it’s not really a tragedy, in the same way that Andersen’s “The Little Match Girl” is a tragedy; these characters are believed to be in a better place now, able to fulfil their potential… but only as ghosts.

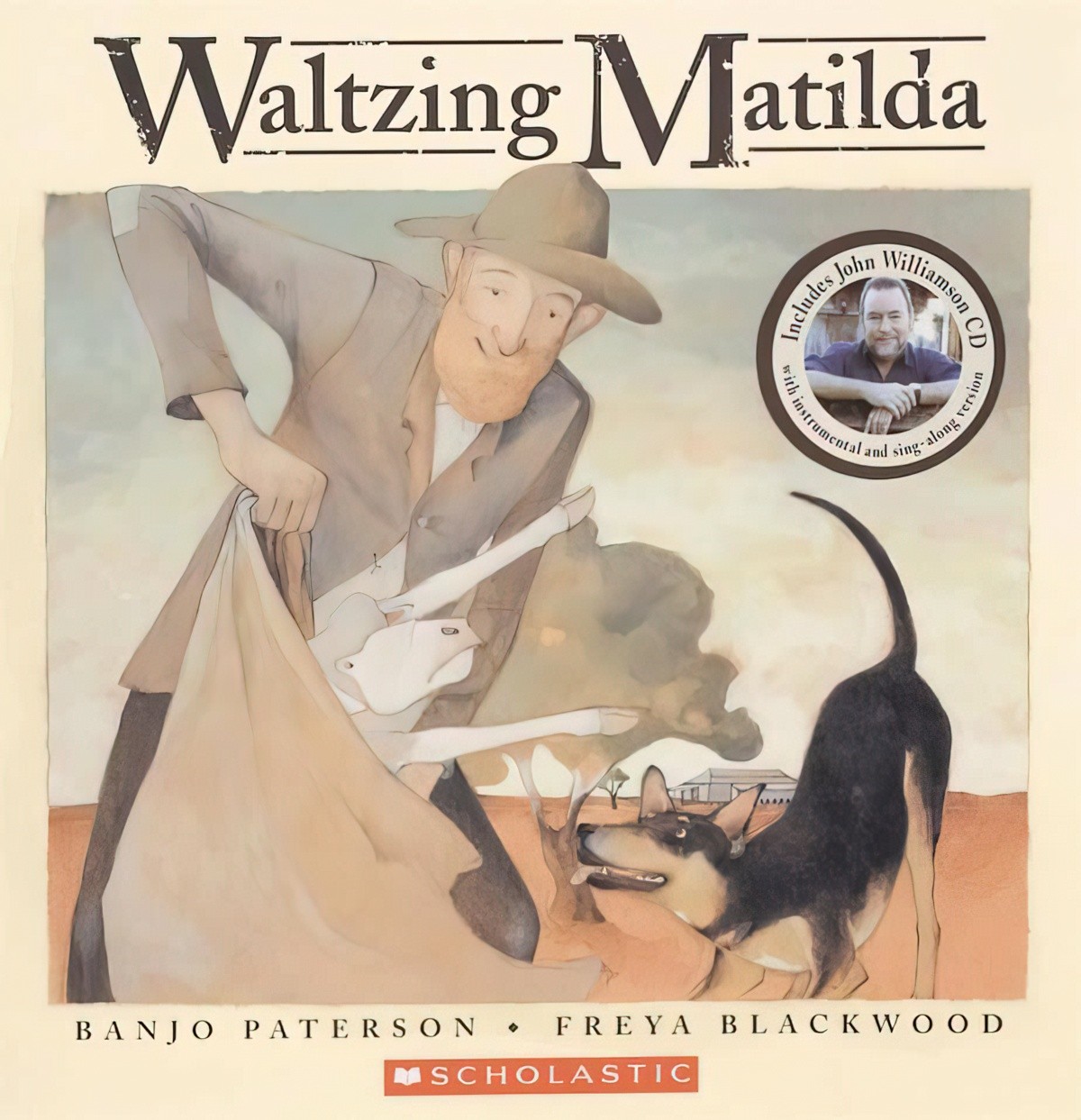

Though my childhood copy of the story is illustrated by Desmond Digby in ‘old master’ style, the song has been more recently illustrated by Freya Blackwood. Blackwood’s style is more oriented to a young audience. Notice the swagman now has a dog, which is not mentioned in the original bush song. However, it’s highly likely he was accompanied by a dog, helping him to bring the sheep down, then sharing the meat.

Anyone with an interest in the story which inspired the bush song can read a non-fiction account by Dennis O’Keeffe.

THEFTS from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966.