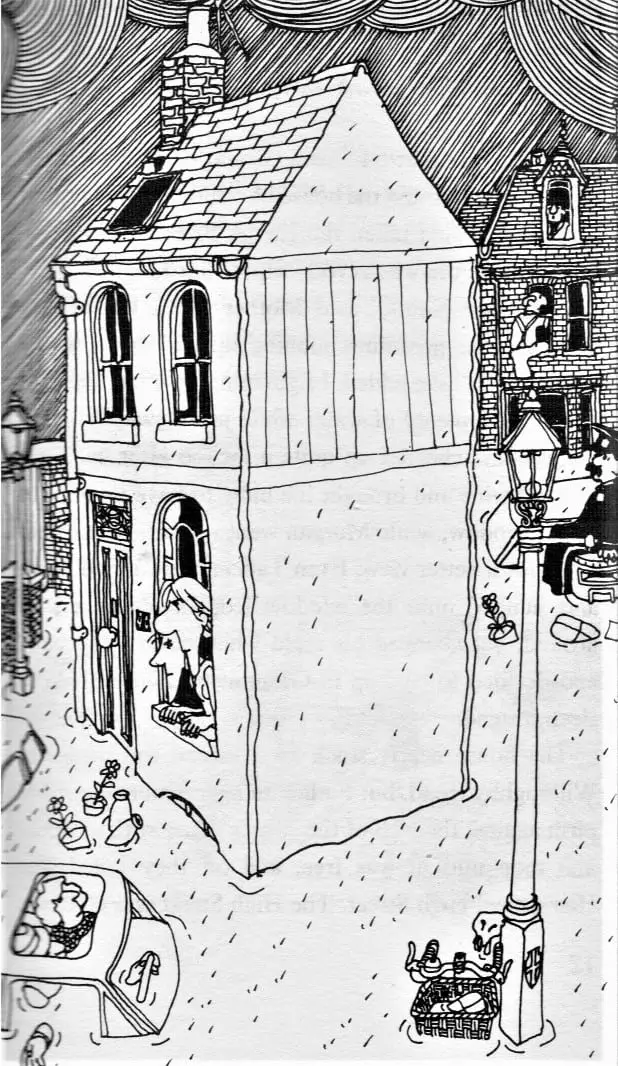

Included in the definition of ‘home’ is the idea of a stable, secure structure… which doesn’t get up and move! The concept of home is especially important in children’s stories, which explains the popularity of the home-away-home structure: Child leaves home, has a little adventure, then returns to security. The young reader falls into slumber, undisturbed by nightmares.

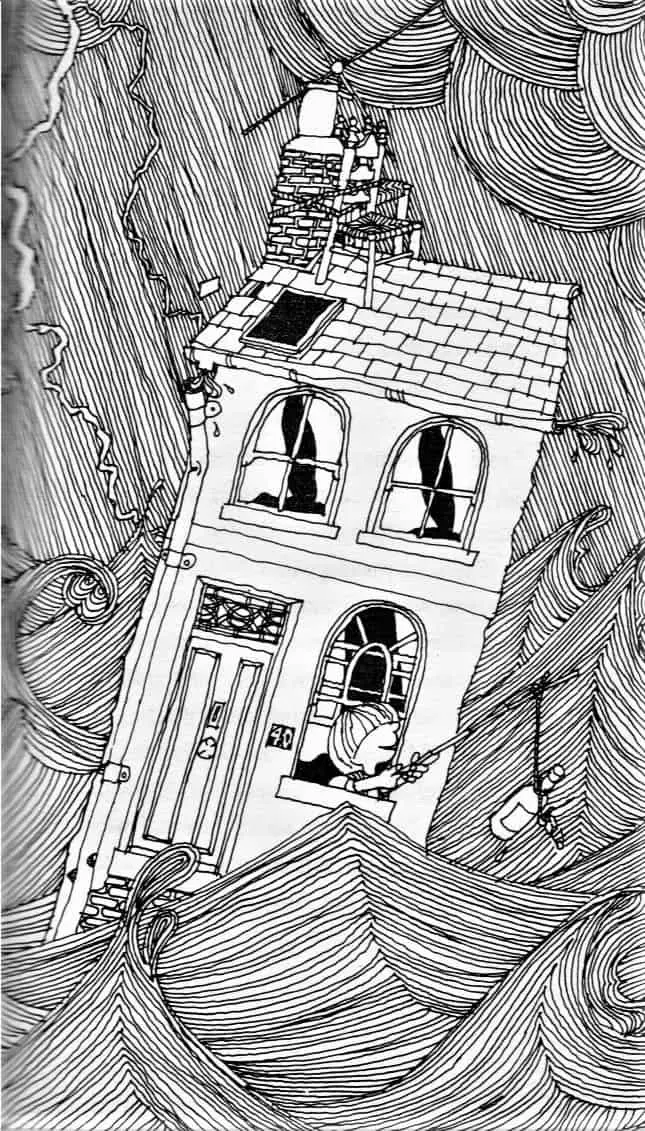

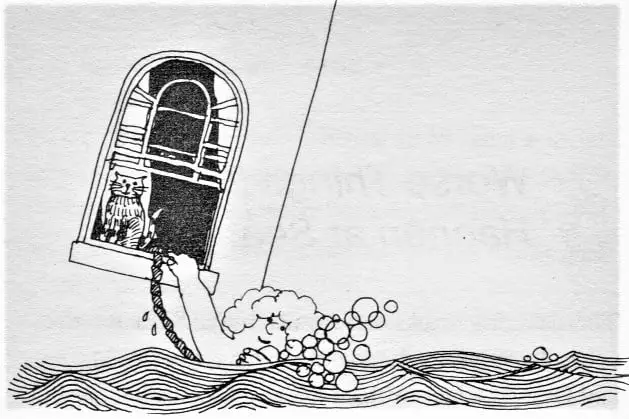

Speaking of nightmares, loss of home base is an enduring theme. We can’t find our home; we return home to find it changed; people we love abandon us. Another creepy take: The home itself gets up and moves. This is the walking house.

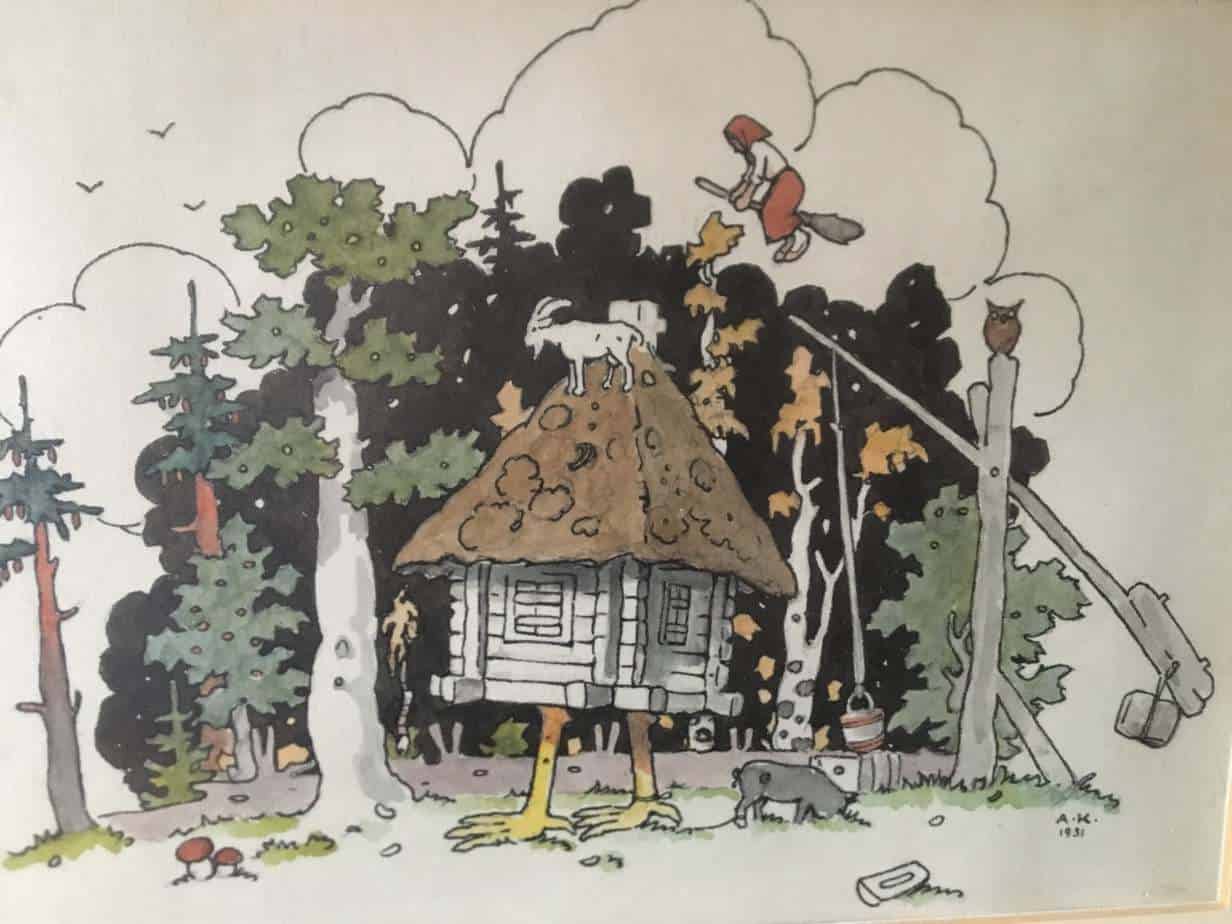

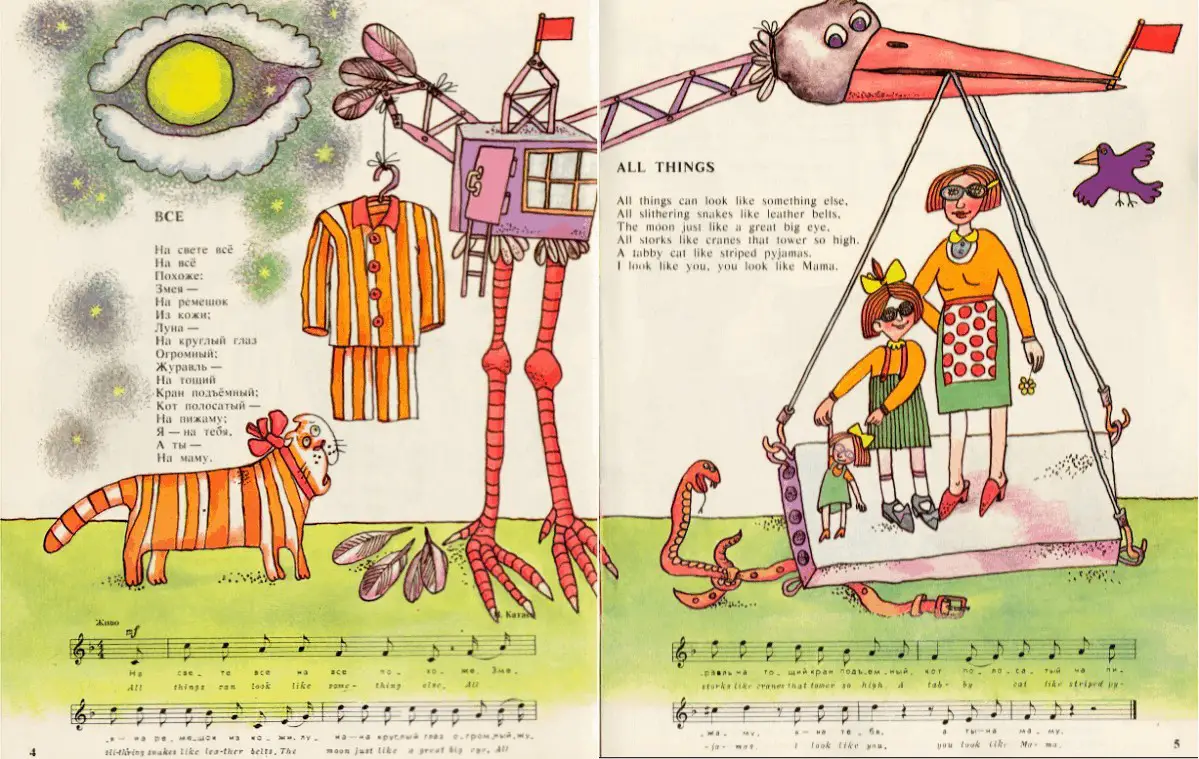

Baba Yaga’s Walking House

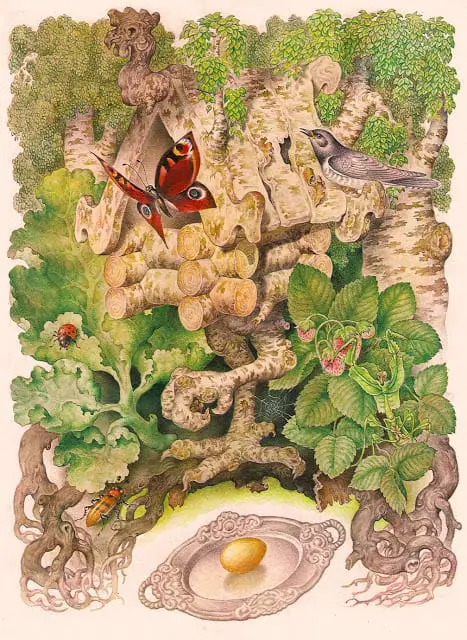

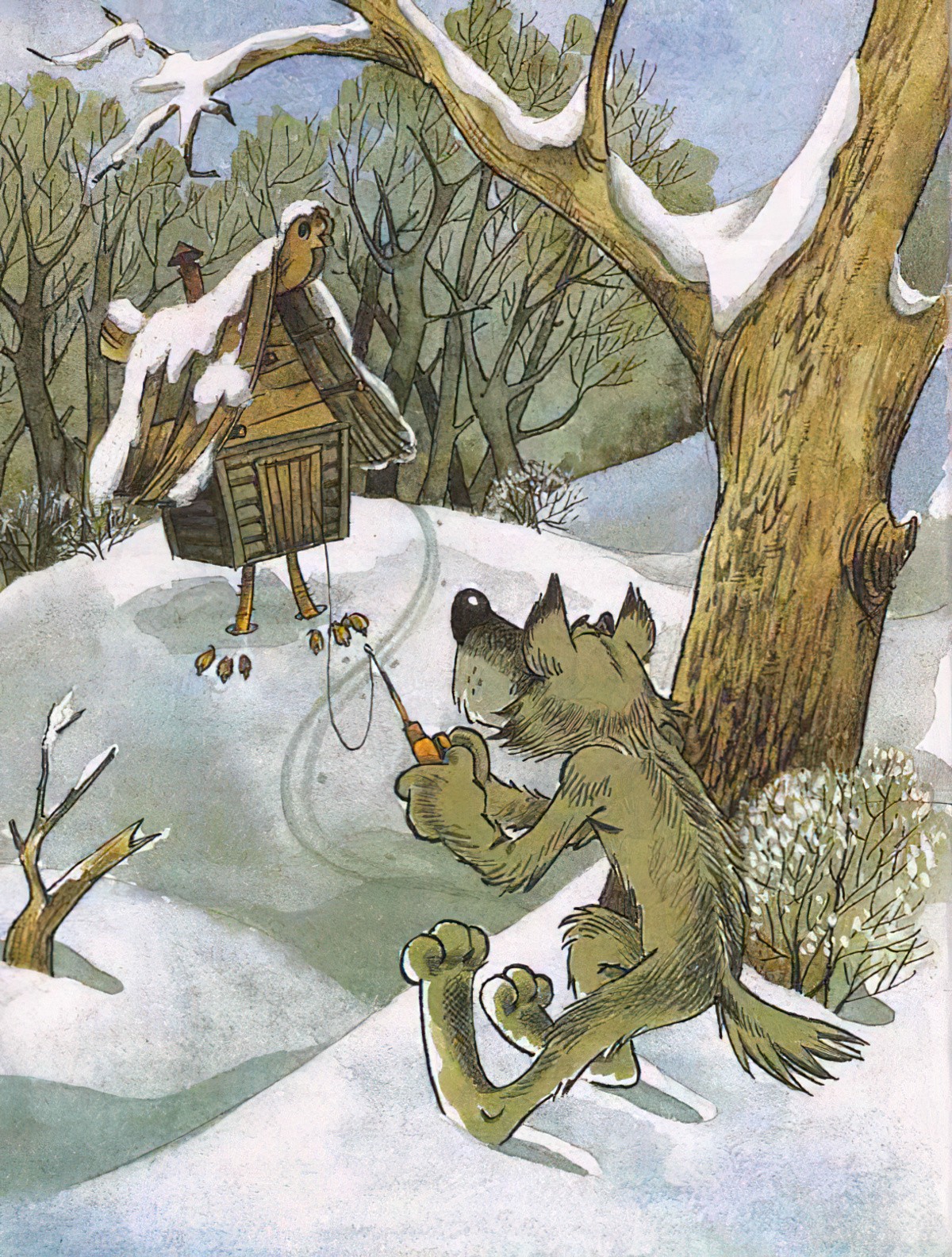

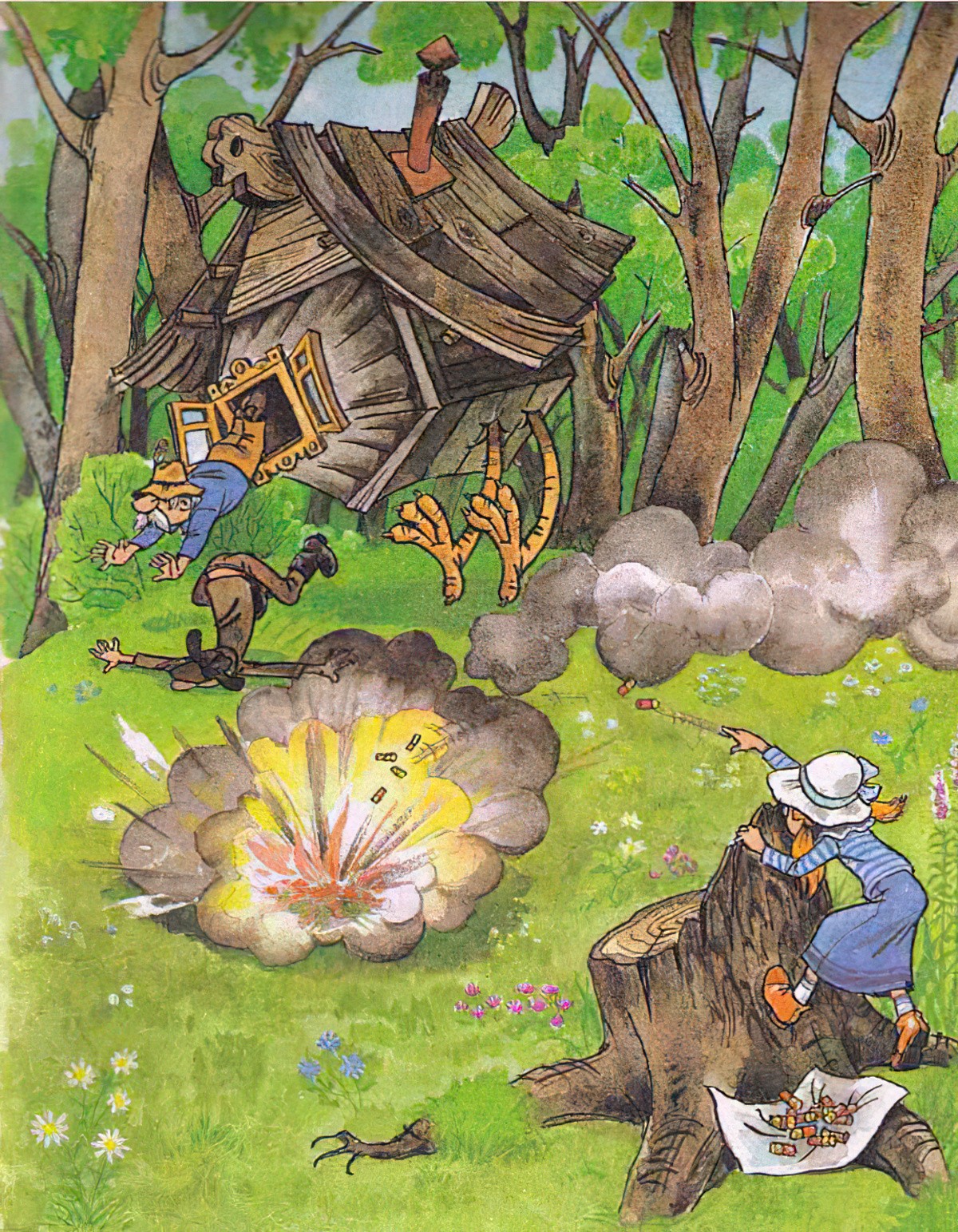

This must be a very old nightmare because we see it in fairytales such as Baba Yaga, who lives in a house on chicken legs. A constant across fairytales: weird feet.

Why chicken legs? Well, why not. Humans have long lived with chickens and we’ve had ample time to notice their creepy-ass feet, more similar to human hands than, say, puppy dog paws, yet birds are more distantly removed in the evolutionary tree. Chicken feet are enough like human hands to lead us into uncanny valley.

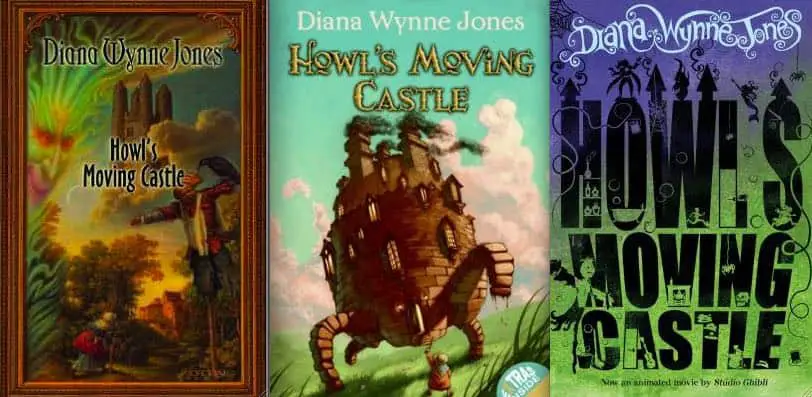

Howl’s Moving Castle

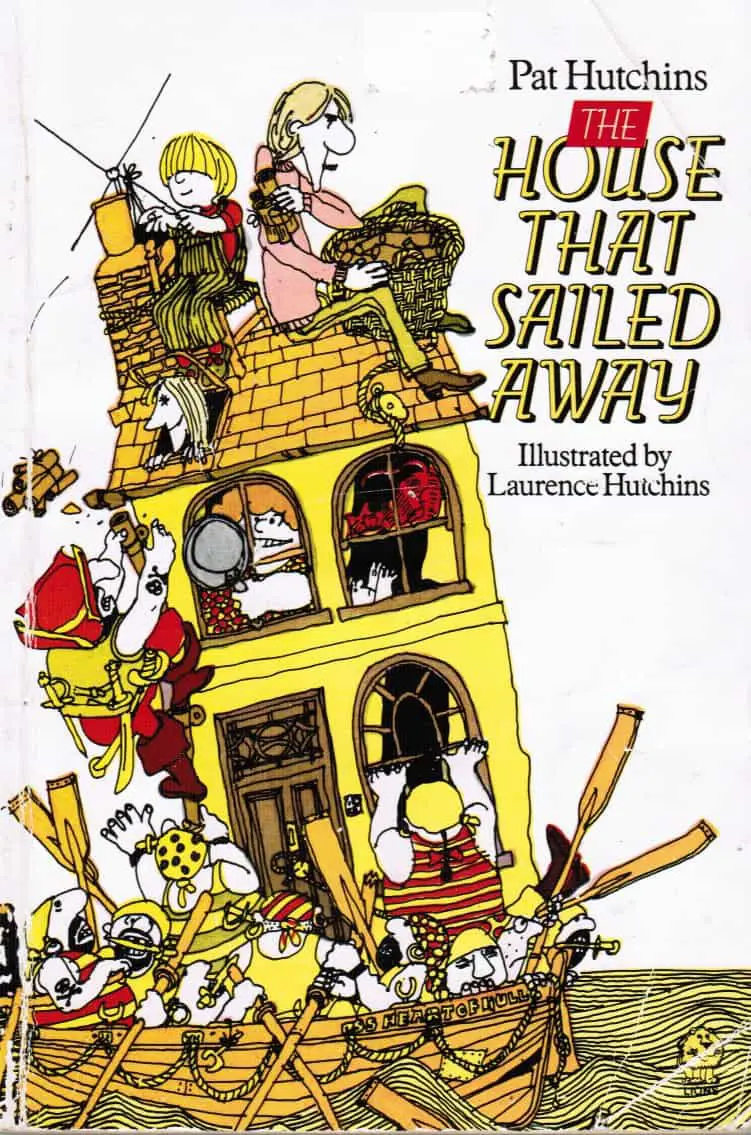

A standout example of a modern walking house is Howl’s Moving Castle by Diana Wynne Jones, published 1986. Later, in 2004, Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki released a film adaptation.

Here is an excellent breakdown of main differences between the YA novel and Hayao Miyazaki’s film adaptation, from a feminist point of view. Though both Miyazaki and Wynne Jones are known to be feminist storytellers, the feminism of the Japanese man is quite different from that of the Welsh novelist.

One thing the film did do though, was to broaden the audience for the novel, which had until then remained relatively obscure.

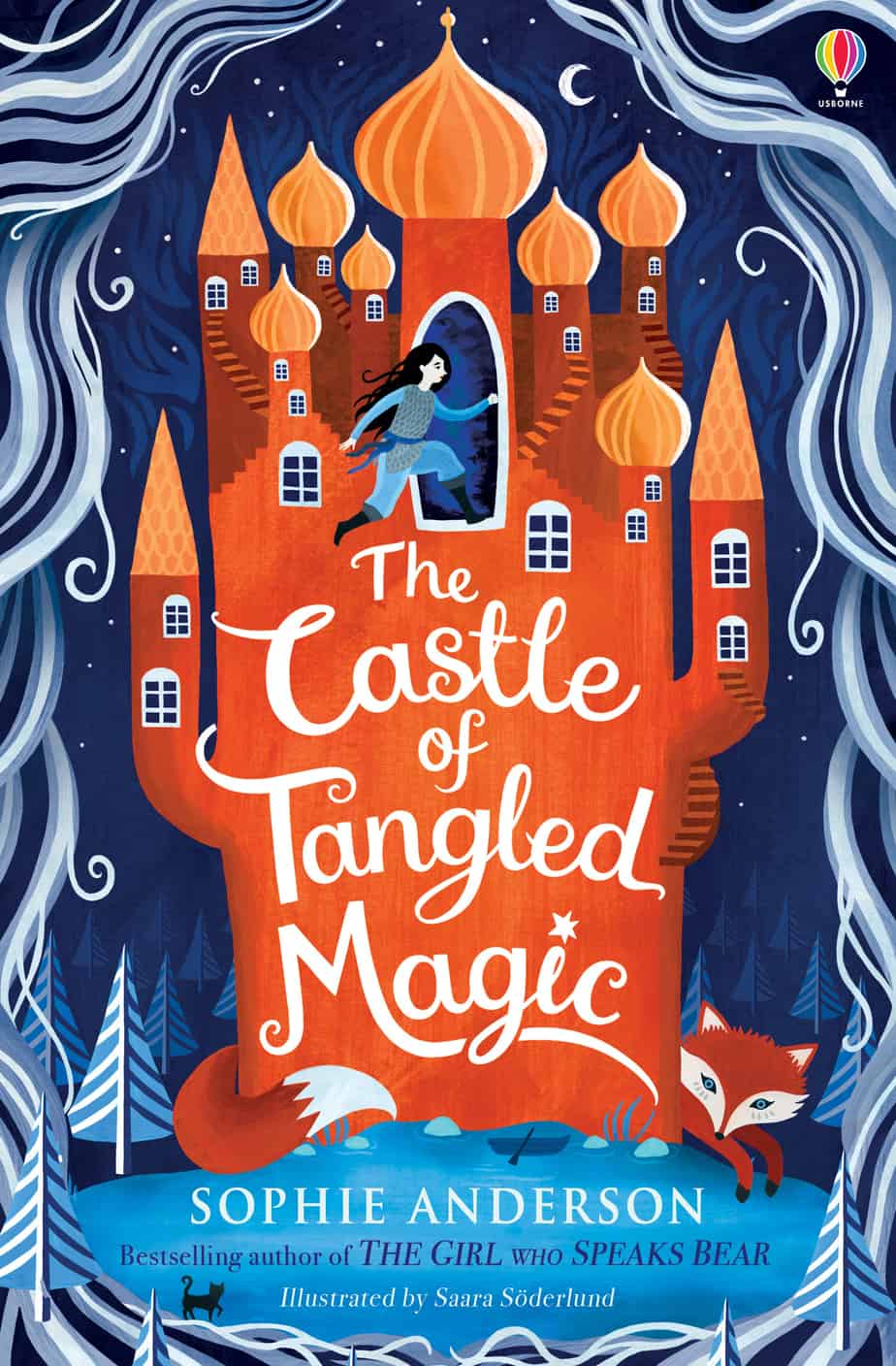

Magic and whimsy meet in this Howl’s Moving Castle for a new generation from the critically adored Sophie Anderson, author of The House with Chicken Legs.

Twelve-year-old Olia knows a thing or two about secrets. Her parents are the caretakers of Castle Mila, a soaring palace with golden domes, lush gardens, and countless room. Literally countless rooms. There are rooms that appear and disappear, and rooms that have been hiding themselves for centuries. The only person who can access them is Olia. She has a special bond with the castle, and it seems to trust her with its secrets.

But then a violent storm rolls in . . . a storm that skips over the village and surrounds the castle, threatening to tear it apart. While taking cover in a rarely-used room, Olia stumbles down a secret passage that leads to a part of Castle Mila she’s never seen before. A strange network of rooms that hide the secret to the castle’s past . . . and the truth about who’s trying to destroy it.

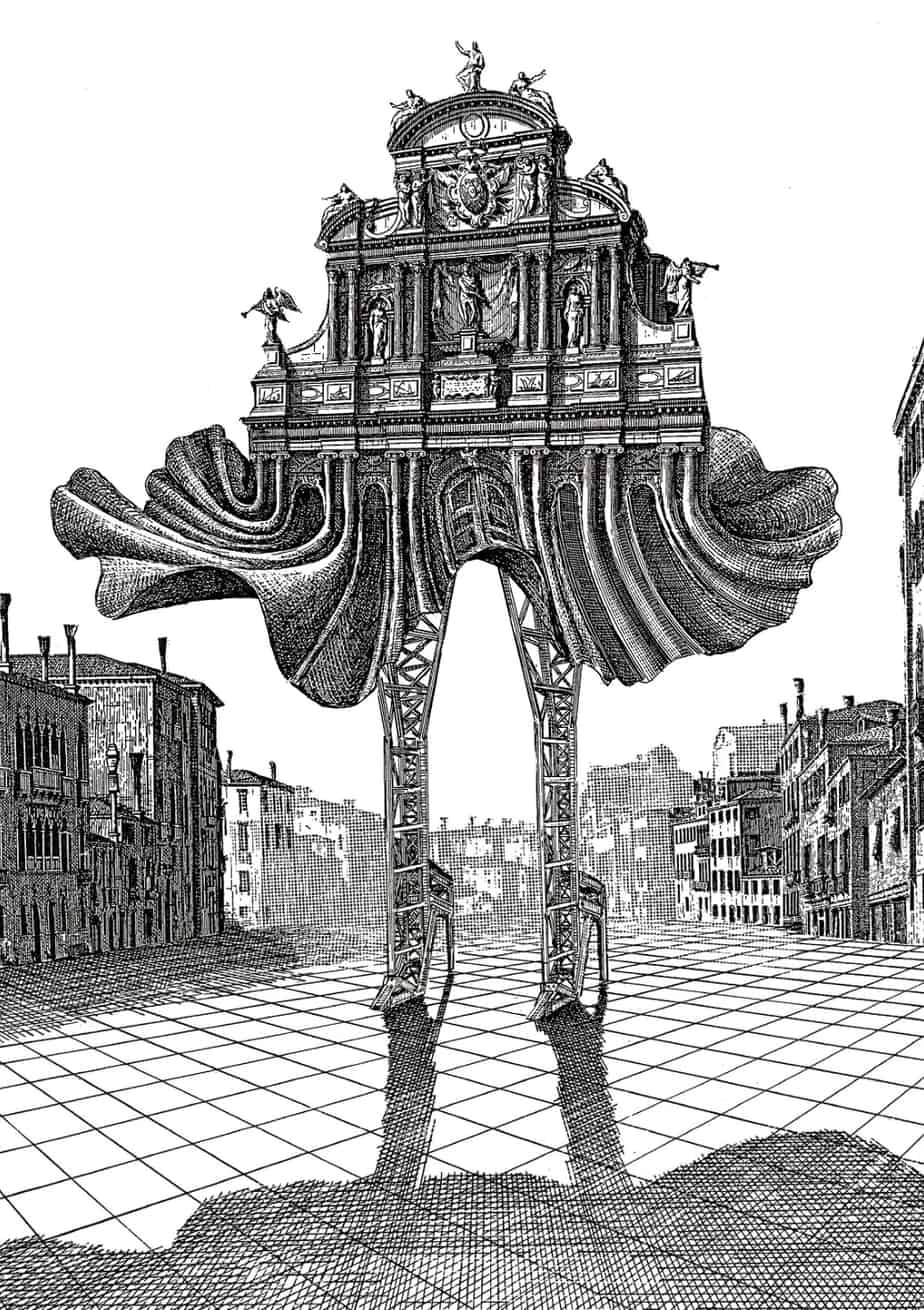

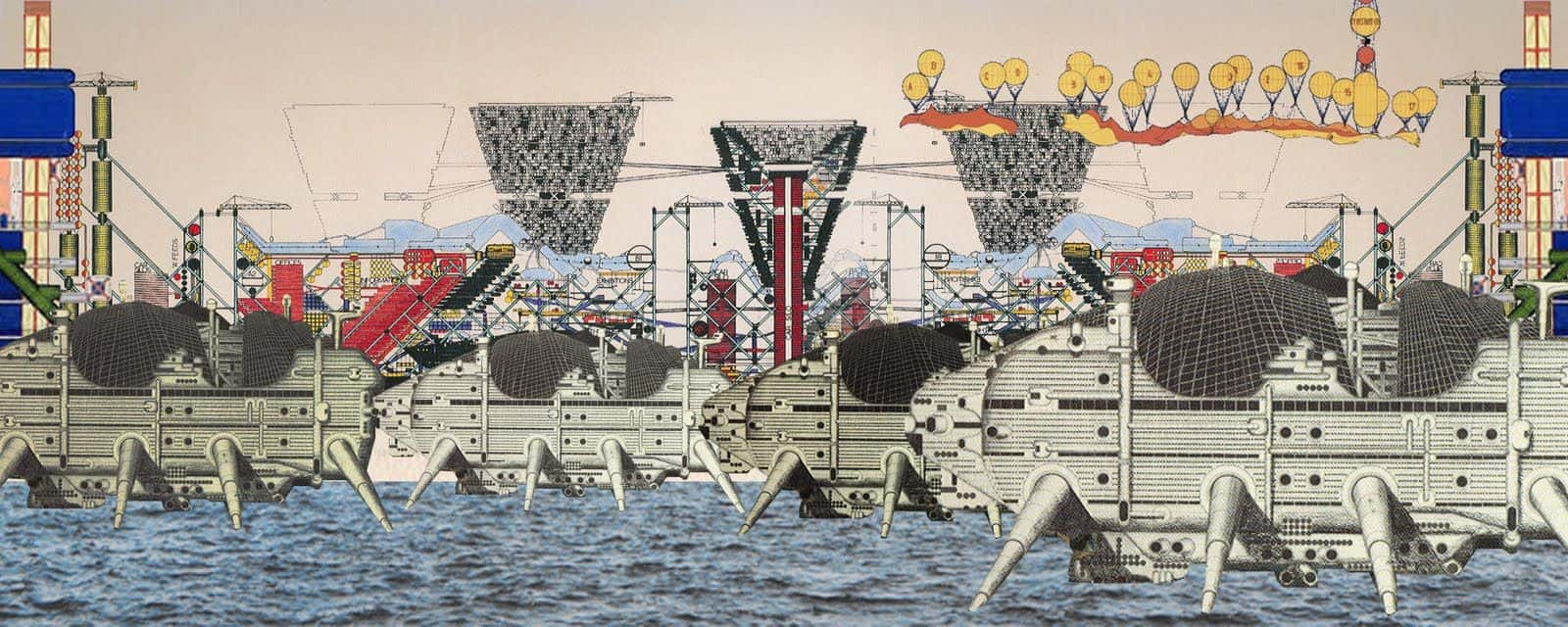

Archigrams

Go back to the 1960s and I wonder if Diana Wynne Jones might’ve been influenced by an architectural-art movement known as Archigram.

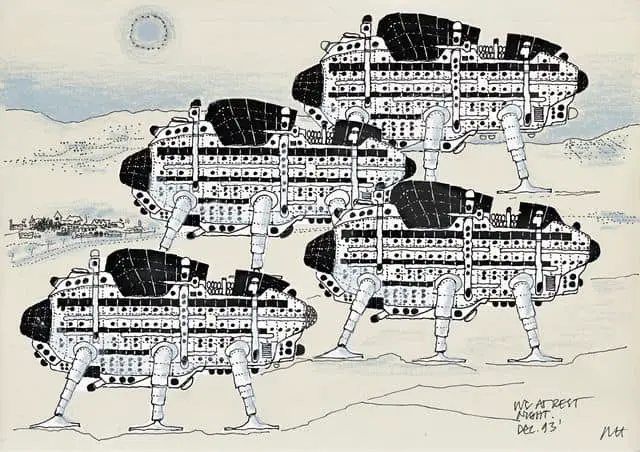

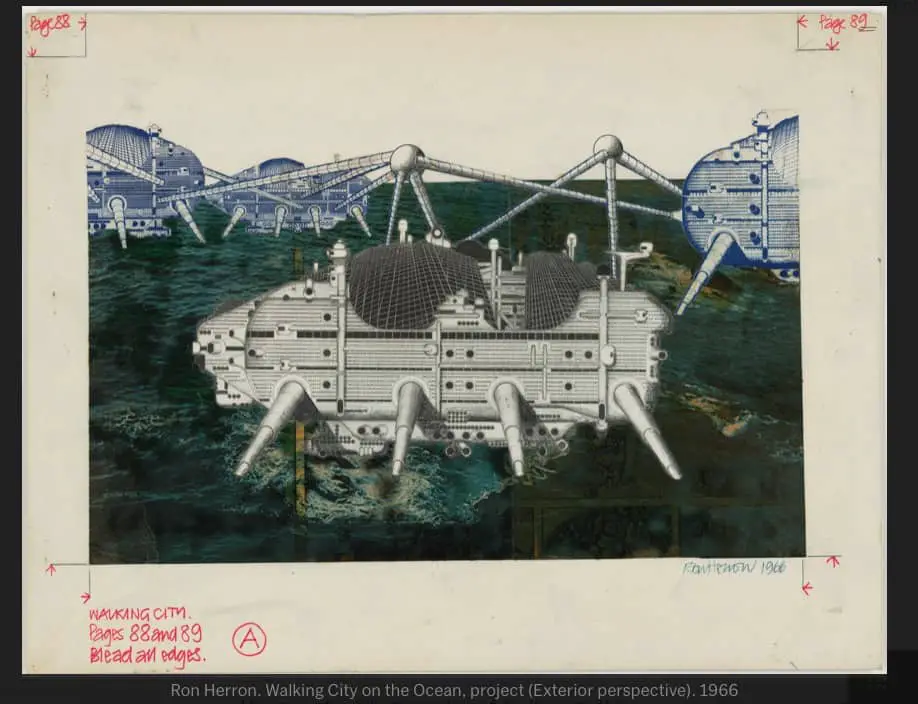

Archigram was an avant-garde architectural group formed in the 1960s that was neofuturistic, anti-heroic and pro-consumerist, drawing inspiration from technology in order to create a new reality that was solely expressed through hypothetical projects.

Wikipedia

In the 1960s they mounted an exhibition called Living City. Archigram wasn’t a green movement — these futuristic thinkers let their imaginations run completely wild, and imagined a future without material or carbon constraints.

The Walking City is constituted by intelligent buildings or robots that are in the form of giant, self-contained living pods that could roam the cities. The form derived from a combination of insect and machine and was a literal interpretation of le-Corbusier’s aphorism of a house as a machine for living in. The pods were independent, yet parasitic as they could ‘plug into’ way stations to exchange occupants or replenish resources. The citizen is therefore a serviced nomad not totally dissimilar from today’s executive cars. The context was perceived as a future ruined world in the aftermath of a nuclear war.

Wikipedia

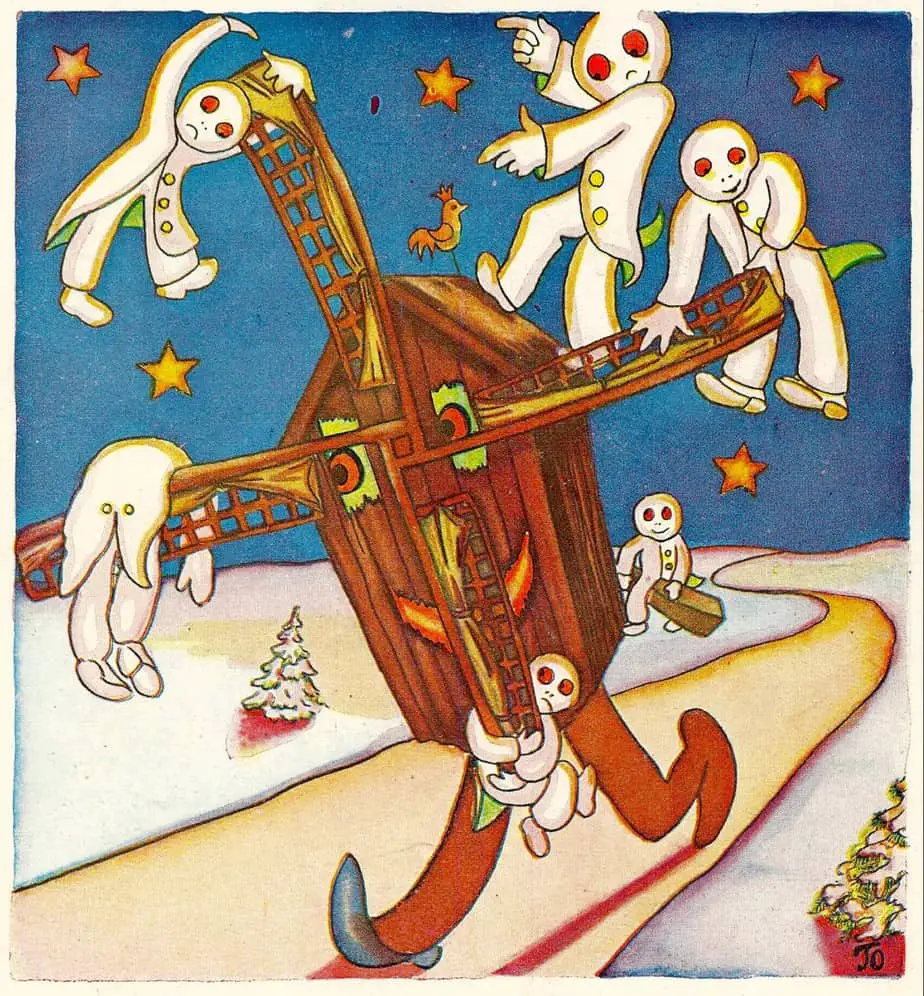

De Wondere Reis Van Een Kerstboom (1942)

Strandbeest

Buildings with legs continue to fascinate.

For the last 27 years, Theo Jansen – a Dutch kinetic sculptor – has been creating new forms of life out of plastic pipes. His beach creatures, called ‘Strandbeest,’ get their energy from the wind.

Mashable

A house legs is what photomontage photographer Scott Mutter might call a ‘surrational image’.