If you weren’t told who wrote “Wake for Susan” (1959), I doubt you’d guess it were by Cormac McCarthy, American author of neo-Westerns and terrifying dystopias, who died on June 13 2023.

The short story is freely available online at Phoenix Magazine. It’s obviously been OCRed in, and retains a few of the scanning errors. That aside, this is not the prose that McCarthy fans have learned to associate with Cormac McCarthy. It has apostrophes in all the ‘right’ places. It has commas galore, including parenthetical commas, more often associated with formal prose. Most un-McCarthy-like.

Basically, by the time he published The Road, McCarthy had developed a Cranky Old Man attitude towards pesky things like commas and possessive apostrophes, throwing conformity to the wind. I think of the older men in my orbit who start wearing caps to shield their bald spots from dripping trees, then around the same time start saying things like “He can wait,” pulling out into intersections willy-nilly, confident that his 30-year-old utility vehicle would come up trumps in a ding. If Cormac’s apostrophe usage is anything to go by, I bet he was that sort of driver.

McCarthy’s punctuation is now a recognisable part of the author’s style:

McCarthy used punctuation sparsely, even replacing most commas with “and” to create polysyndetons; it has been called “the most important word in McCarthy’s lexicon”. He told Oprah Winfrey that he preferred “simple declarative sentences” and that he used capital letters, periods, an occasional comma, or a colon for setting off a list, but never semicolons, which he labeled as “idiocy”. He did not use quotation marks for dialogue and believed there is no reason to “blot the page up with weird little marks”.

Cormac McCarthy, Wikipedia

I don’t mind the polysyndetons at all, but I am annoyed by stylistic decisions which make reading just a bit more difficult than it need be.

I recently finished reading Eyrie by Tim Winton, a celebrated Australian author who has followed this trend of leaving out dialogue punctuation (and also been part of promulgating it). This works okay for the first part of the novel, but once the cast of characters grows larger, and readers face entire pages of unattributed dialogue, character voices merge together and as reader you lose the ability to know who’s saying what. I found myself literally counting back the lines to figure out who was speaking. After a while I resented this task and began to not care. If this was the point, I don’t like it. (For context, Eyrie is about a drug- and drink-addled white man who wanders around drug- and drink-addled-ly.)

I get the sense that this minimalist attitude towards punctuation skews masculine, as in, it’s mostly male authors who have taken this up (and also a few woman authors who write with what I’d describe as a butch style). Punctuation, it seems, like adjectives, are a feminine concern, like literary doilies clogging up the joint, collecting dust. Alpha masculinity requires a veneer of Stoicism, a Don’t Care attitude, “I’m focused on the big picture”, “I’m not here to make your life easier, I’ve got more pressing things to worry about that whatever the hell you learned about punctuation in grade school.”

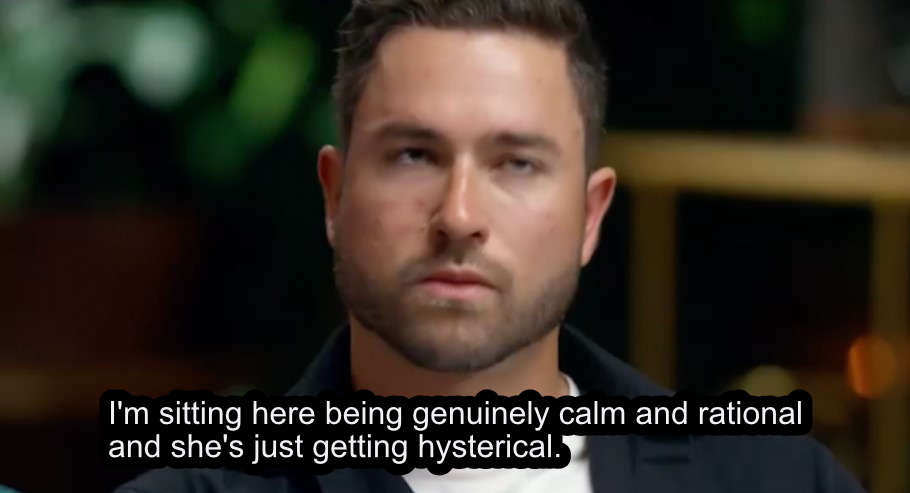

If I’m honest, this stance mostly annoys me because guys like Harrison of Married at First Sight 2023, who avoid emotion on their faces, any semblance of punctuation in their speech, and use this Don’t Care attitude to take the moral high-ground:

Well sure, leave out dialogue attribution and speech marks if your character voices are sufficiently differentiated. Go ahead, leave out apostrophes while you’re at it. But leave them all out, not just some. What sort of sway must McCarthy have enjoyed with his publishing houses? Line editors didn’t correct him. Was the narrator of The Road supposed to be a guy who couldn’t be bothered with annoyances like punctuation because, let’s face it, he had the End of the World to worry about? Was McCarthy’s annoying punctuation some kind of political stance? I dunno.

But after reading this early McCarthy short story, I do know this: When Cormac McCarthy was an early career author, either one of the following was true:

- Editors fixed his punctuation to conform to the common standard of the day.

- Cormac McCarthy had learned and fully understood the ‘rules’ of punctuation, but was only allowed by editors to not care about that guff after he’d established himself as a best-selling author.

I did the arithmetic for you. McCarthy was 26 when “Wake for Susan” went to print. Apparently this is his first published story. Rusted-on McCarthy fans looking for anything and everything he wrote are frequently surprised to find it, if Reddit threads are any guide.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “WAKE FOR SUSAN”

Basic structure: Walk in woods. Long daydream. More walking in woods.

It’s mid-October, morning. A seventeen-year-old called Wes is up and about surprisingly early, given the circadian rhythms of teenagers. Or maybe that’s a 21st century thing. This story is set in the 1950s.

Wes is out hunting for squirrels, but the squirrels aren’t silly enough to be up yet. walks home along an abandoned railway track, which is always a scene that puts me in mind of Stand By Me, except this boy is on his own. That’s important. On their own, boys are different in the woods. Also, he’s basically a man. In the 1950s, seventeen-year-old boys know men who lied about their age and went to war.

This guy is really enjoying nature. Unlike City Kids Today (TM) he knows the names of the foliage. He is at one with his environment. Cormac McCarthy’s description of settings only strengthened as his writing career progressed. This story shows it was there from the very start. This environment isn’t entirely ‘natural’ — there’s a touch of dystopia about it. There’s a quarry nearby (which I personally associate with dystopia, increasingly so) and he’s walking along a disused railway track, with ‘sagging rails’.

After some time, Wes happens upon a spent bullet from an old-timey gun (a hog rifle). He wonders if it had been used to shoot an Indian. (Despite the outdated term, it’s at least something to remember that horrendous violence happened on American turf.)

He concludes the bullet is probably more recently spent than that, and its backstory is probably less dire than the one he first imagined. Someone was probably out hunting for food. Readers now understand Wes’s frame of mind. He’s in a contemplative mood, and he’s about to get creative.

Wes wanders on until he happens upon a graveyard, mostly hidden to anyone who doesn’t already know it is there. He’s stumbled upon it once before with an acquaintance, and the bullet prompts him to find it again. Notably, the graveyard isn’t where he remembers it. There’s something ever-shifting, ephemeral about graveyards, which Michel Foucault considered heterotopies.

Why is a cemetery a heterotopia? Because there is an entry criteria (you have to be dead, well, ideally). People of different backgrounds lie peacefully together, which creates for the living the simulation of a perfect town. Also, a cemetery gives the illusion to its visitors that their departed relatives still have an existence and status, symbolised by the stone of their tomb. This is a simulated utopia of life after death, but it is also a representation of the real world.

Here in the graveyard, scrubby pines grew boldly within a circle of oaks and hickories. The stones nestled secretively beneath the tangled honeysuckle. They were moss-mellowed and weather-stained in that rustic way which charms lovers of old things.

Wake for Susan

So when Wes seeks out this cemetery, he’s wanting to experience a little calm, a little order, a little Romance.

Trivia for you: A cemetery is different from a graveyard in that a graveyard has a church connected to it, while a cemetery does not. A boneyard is different again, having nothing to do with bones but is rather a place for disused or decommissioned machinery.

In this abandoned graveyard Wes finds (relocates?) a stone marked with the name of a woman who died at the age of seventeen in 1834. Knowing no facts of her life, other than the bare basics inscribed on her gravestone, he slips into a reverie in which he imagines (concocts) the life story of Susan Ledbetter.

He earlier found a “lead” bullet, which makes me think he has found her grave before, the homophone of “lead” reminding him of “Ledbetter”. Susan’s name may also be meaningful in the sense that he imagines a life which is “better” than the one she really “led”.

To imagine Susan’s life, Wes must mentally capitulate himself back into the early 1800s which, from his 1950s perspective, doesn’t feel so long ago. He can do that.

The image of the perfect girl in the 1950s was a blonde, blue-eyed cheesecake pin-up, and this is exactly who he imagines. He also imagines a table spread full of delicious food from an earlier time. Notably, he does not imagine slim pickings, let alone starvation. In the mind of Wes, the 1830s are a Prelapsarian time, decades before America’s civil war, before the more recent World Wars. (Only a white boy would consider the 1830s in this particular light.)

After Wes laments and fabulises the short life of a stranger who died he continues on his way.

ANALYSIS

I can see how this sentimental narrative annoys some (misogynistic) readers. It is a feminine thing to launch into a daydream about a lover. And many McCarthy fans don’t come from a masculinity which allows for sentimentality. The nature-appreciating daydreamers of fiction tend to be feminine. Also, he literally hugs the gravestone and cries. Boy’s got some stuff going on.

Generally, modern readers have less time for the flaneur, who is more typically strolling around the city, observing others, thinking about things in a leisurely way. McCarthy has created a rural version of the flaneur.

Other fans are far more charitable about this early McCarthy short story, and one Reddit commenter pinpoints “Wake for Susan” as “the emotional seed of All the Pretty Horses“.

I wonder how the author feels about his own creation of Wes. The phrase “and the lover looked strangely like Wes” indicates to me that McCarthy is standing back from this seventeen-year-old boy and inviting readers to regard him from some distance, inviting us to see more about Wes through his slightly ridiculous daydream, not to take away some deep message about how great the early 1800s must’ve been.

At the same time, McCarthy avoids poking fun at the kid. I wonder if, even by the age of 26, McCarthy himself had already lost a good deal of the Romantic notions he himself may have held at the age of 17. Born in 1933, McCarthy himself was 17 in the year 1950. For everyone of that generation, the teenage years were filled with talk of war and death, and young lives cut short, senselessly wasted. For a seventeen-year-old boy of that time, there was no guarantee that he would himself live to be an old man.

I have mixed feelings about this story. In one way, “Wake for Susan” is a subversion of masculine “rules”. That’s great. But also, I’m reminded of how McCarthy was very much a white man influenced by the gender hierarchy of the 1950s, which of course positioned men at the top. Feeling the feels for a dead girl subverts the expectation that boys are all about doing, not moping around thinking about love. But the way Wes imagines the young woman is a bit vom.

FEMALE/FEMININE CHARACTERISATION

I was planning on writing about a woman for 50 years. I will never be competent enough to do so, but at some point you have to try.

Cormac McCarthy interview in The Wall Street Journal, 2009

Setting aside that this is a female character who functions primarily as a love interest for a man (which may perhaps be part of the point, existing as she does in a male character’s fantasy), Susan seems developed and real for a story of this length – which doesn’t happen often for female characters of McCarthy’s fiction.

Jarslow on Reddit

I really liked “Wake for Susan”. It’s very… gentle compared to his other work.

trevester6

it’s a lot more embellished than I’m used to of McCarthy’s work. It’s well written and pretty for sure, but I prefer his stark and simple syntax in his later works. I’m not sure if this is necessarily true, but I think it’s interesting to note that McCarthy’s language is a lot more flowery in his first published piece — perhaps because young writers feel the need to overdo things like that? That just because they can write using “big” words and overwrought imagery, they feel that they should?

eggsaladbob

I would no doubt have a more charitable view of Wes if I knew nothing of McCarthy’s life. I feel the author’s love life offers some explanation of McCarthy’s decreasing literary interest in the interiority of woman characters, or even in having women on the page.

Women, I am repeatedly told, don’t like – don’t get – Cormac McCarthy. It’s the kind of patronising nonsense that gets levelled at us when we point out the converse: that McCarthy’s fiction doesn’t get – doesn’t like – women. When female characters do appear in his pages, they are cowards, victims and sexpots: sirenic doom-bringers, cheetah-owning dommes, simpering twits and bad mothers. It’s often possible to admire the Pulitzer prize winner despite his paper-thin girls (see also Roth, Updike, Mailer and all the other cocksure Americans).

Stella Maris by Cormac McCarthy review – a slow-motion study of obliteration, review of Stella Maris by Beejay Silcox in The Guardian 2022

CORMAC MCCARTHY’S REAL LIFE WOMEN

Cormac McCarthy was married to Lee Holleman for one year, in 1961-62. The couple divorced soon after the birth of their son, Cullen. Why? We know from Lee’s obituary (published many years later, when she died at age 70) that while caring for their baby and also doing all the housework, Cormac required Lee to also get a paid job so he could focus on his novel writing. He’d had this short story published after all. He was a big writer now.

McCarthy next married Annie DeLisle, a British vocalist (in a band called the Healey Sisters) who he met while travelling in Europe on a fellowship. Cormac and Annie stayed together for eight years, though the divorce wasn’t finalised until they’d been married for fifteen.

Annie had moved to America rather than Cormac move to Britain, so she had no support network. Together they lived in poverty on a dairy farm outside Knoxville, Tennessee while Cormac continued to write. (We can probably guess who did the house and farm work.) Despite Cormac failing to earn enough money to even eat properly, Cormac would turn down opportunities (e.g. speaking gigs) which would have paid him well. Oh yes, and Cormac had been drinking heavily throughout this period. The couple separated in 1976. Cormac moved to El Paso.

Finally Cormac married Jennifer Winkley in 1998. Thirty-two is the magic number here: Jennifer was 32 at the time, exactly 32 years younger than Cormac. Together they had a son (Cormac’s second). They called him John, born the following year in 1999. The Road is dedicated to this son, and many of the lines come directly from him. Cormac’s marriage to Jennifer lasted eight years. They divorced in 2006.

After three marriages it would be literally impossible for a man to retain the romantic notions of femininity McCarthy’s character Wes espouses here, with a wifey in the house completing tasks without hardly noticing she’s completing them because she’s thinking about a man. I think it’s clear from the trajectory of McCarthy’s work that he became more jaded regarding women as time wore on, unfortunately accumulating a large following (though a small proportion of the total) who loved that exact thing about him. So when those guys go back and read this one, written when McCarthy was himself young and somewhat optimistic about romantic love, they’re disgusted.

THE EROTICS OF SILENCE

At the door her kiss would be full of meaning

“Wake for Susan”

I don’t know if there’s a well-known phrase to describe the Romantic notion that true love does not require communication. In individualistic societies like America, this sentiment has gone well out of fashion. We are all told now that in relationships communication is key. Don’t mind-read. The #metoo movement very recently took us one step further, asking for more communication specifically around sex.

That said, I suspect the ideal of a love so strong no words are required remains the private fantasy of many people, even in the West.

Wes embodies the romantic expectations of manliness he inherited from wartime thinking: that true lovers don’t even need to agree that they like each other, let alone that they’re any kind of couple:

No words of love passed between them, and at night when he kissed her standing there on the stoop and wheeled around and headed for the gate, it seemed that he must tell her how he felt. He would turn at the gate and look back and see her standing luminescent beneath the autumn stars and he wanted to run back and crush her in his arms and whisper wild things in her ear. But he simply raised his hand and she hers, and he ambled home emptily beneath wind-tortured trees that spoke in behalf of the silent stars.

“Wake for Susan”

A cultural shift happened in romantic and married relationships between Baby Boomers and Gen X. This change happened during the late 1960s and continued gradually through the 1970s. This is known as the shift from the Capstone to the Cornerstone model. (I summarise it here, after listening to Esther Perel talk about it.) Basically, people of McCarthy and Wes’s generation met and married young, then grew up together. Partners were symbolically two halves of the same person. In contrast, contemporary couples work on themselves and meet each other when they’re ‘a good catch’, with careers and a self-identity and so on. Partners no longer consider themselves ‘two halves of the same person’.

But when Wes hugs that gravestone, I don’t think he’s simply lamenting the reality that he can never have Susan. He kind of is Susan. Understanding is another word for love. Although Susan’s story happened entirely in Wes’s imagination, he feels he understands her. He’s basically practising the skill of empathy, which requires that we temporarily become one (mind meld) with the object of our attention.

A GOOD CRY

Women cry more than men (on average) but men cry more than you’d think. The difference is, men are shamed for it. But here we are shown a young man who has a good cry while safe on his own where no one can hear and feels all the better for it afterwards.

I suspect he’s been pining for a girl in the here-and-now, and that the story he concocted is the story of himself and the here-and-now girl, but that’s extrapolation on my part.

REFERENCES

Why Is This Good? podcast (they like the story more than I do)