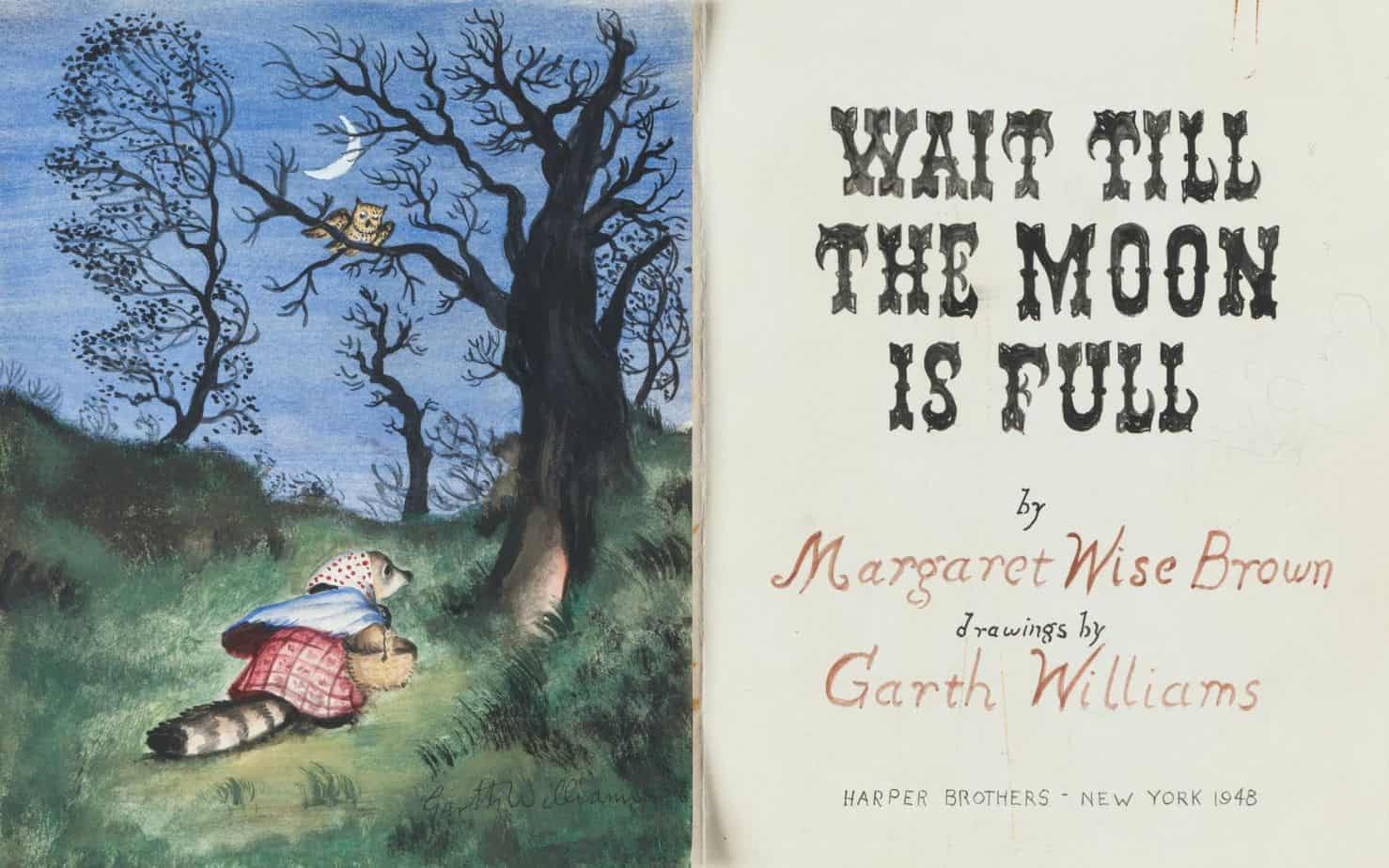

Wait Till the Moon Is Full is a 1948 picture book written by Margaret Wise Brown with pictures by Garth Williams. The story has carnivalesque elements, a gentle utopian storyline and a well-drawn mother figure, who is safe and warm but who also joins her son in his imaginative play.

This picture book is a perfect going-to-bed story because of its poetic elements. For this reason it has been produced as an audio play. It works even without illustrations.

SETTING OF WAIT TILL THE MOON IS FULL

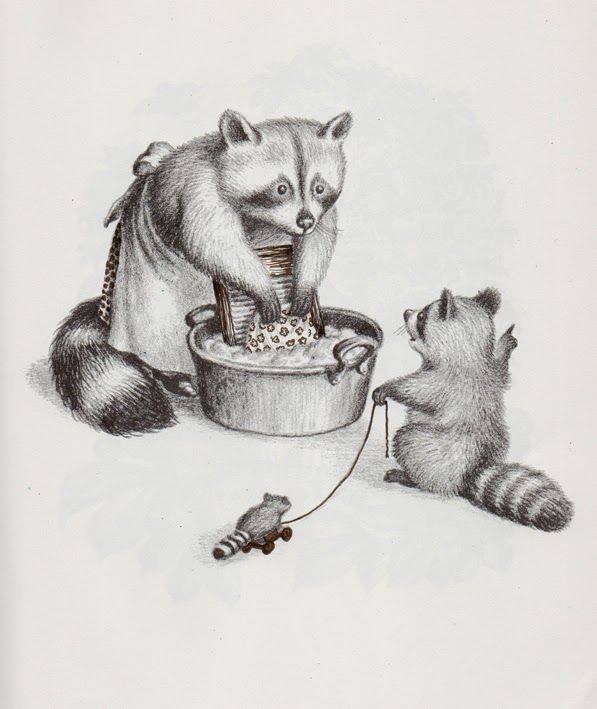

- PERIOD — The technology is clearly mid 20th century, where mothers do the handwashing (and probably spend an entire day doing it).

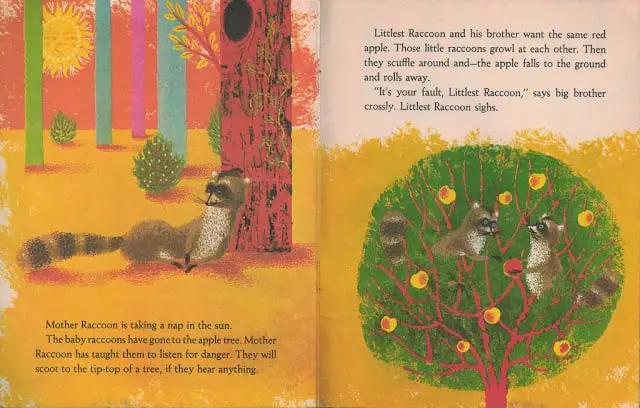

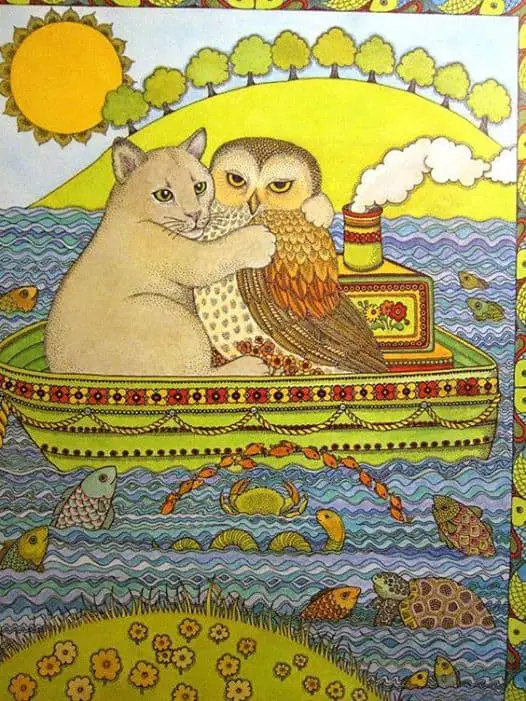

- DURATION — A month. The moon is central here. We can assume it’s a month, though I think it’s a month with poetic licence. The little raccoon has time to get nice and plump.

- LOCATION — The racoon lives in a big chestnut tree ‘with his mother, who was also a raccoon’. (This detail about the species of the mother is exactly the sort of unexpected and comically redundant detail I’ve learned to expect from Margret Wise Brown.)

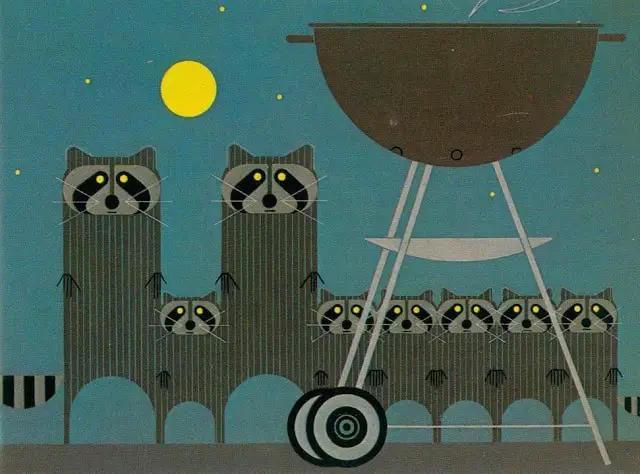

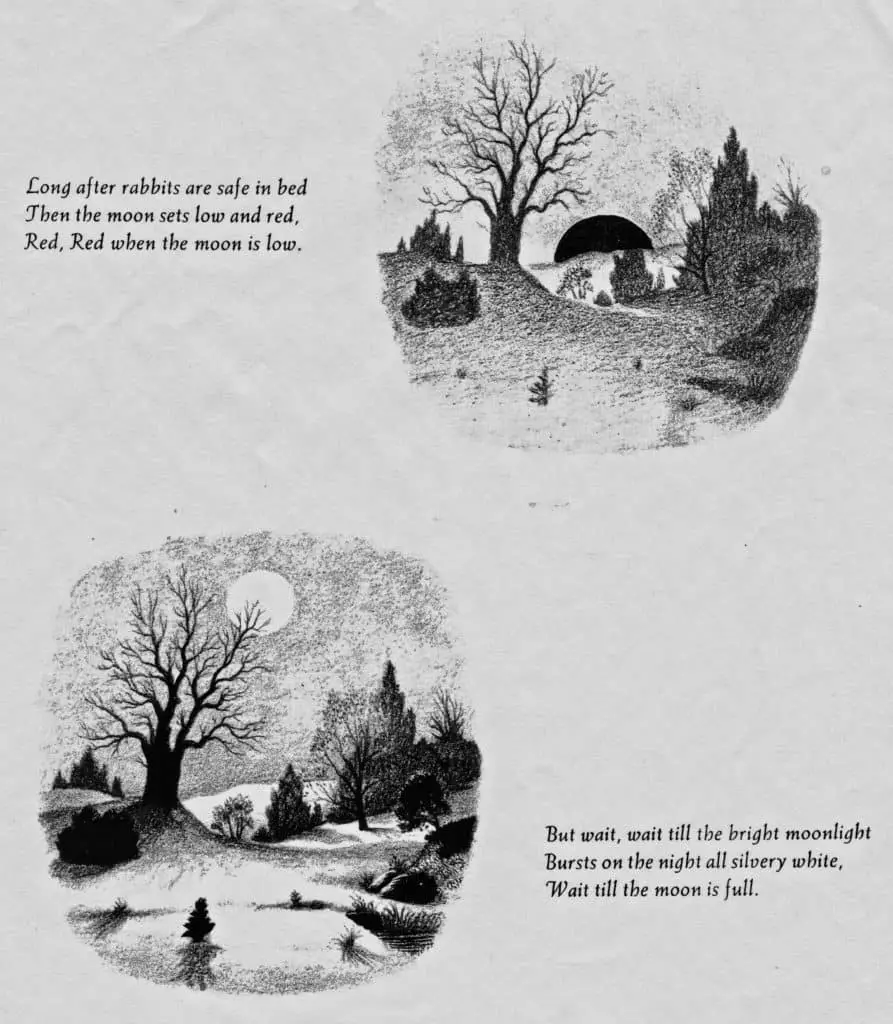

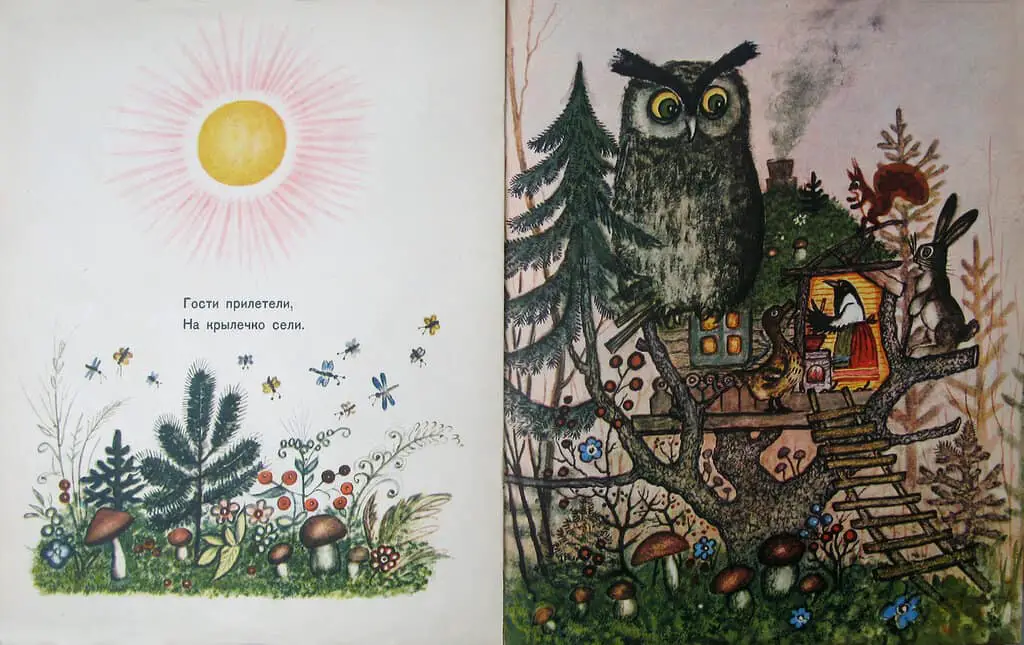

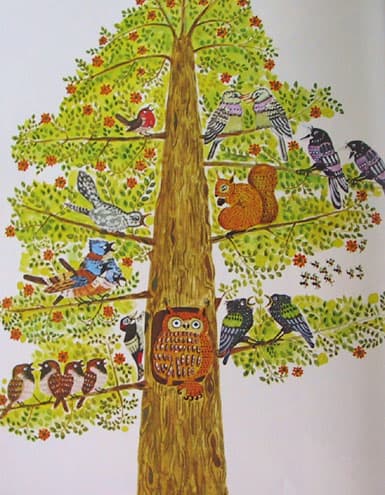

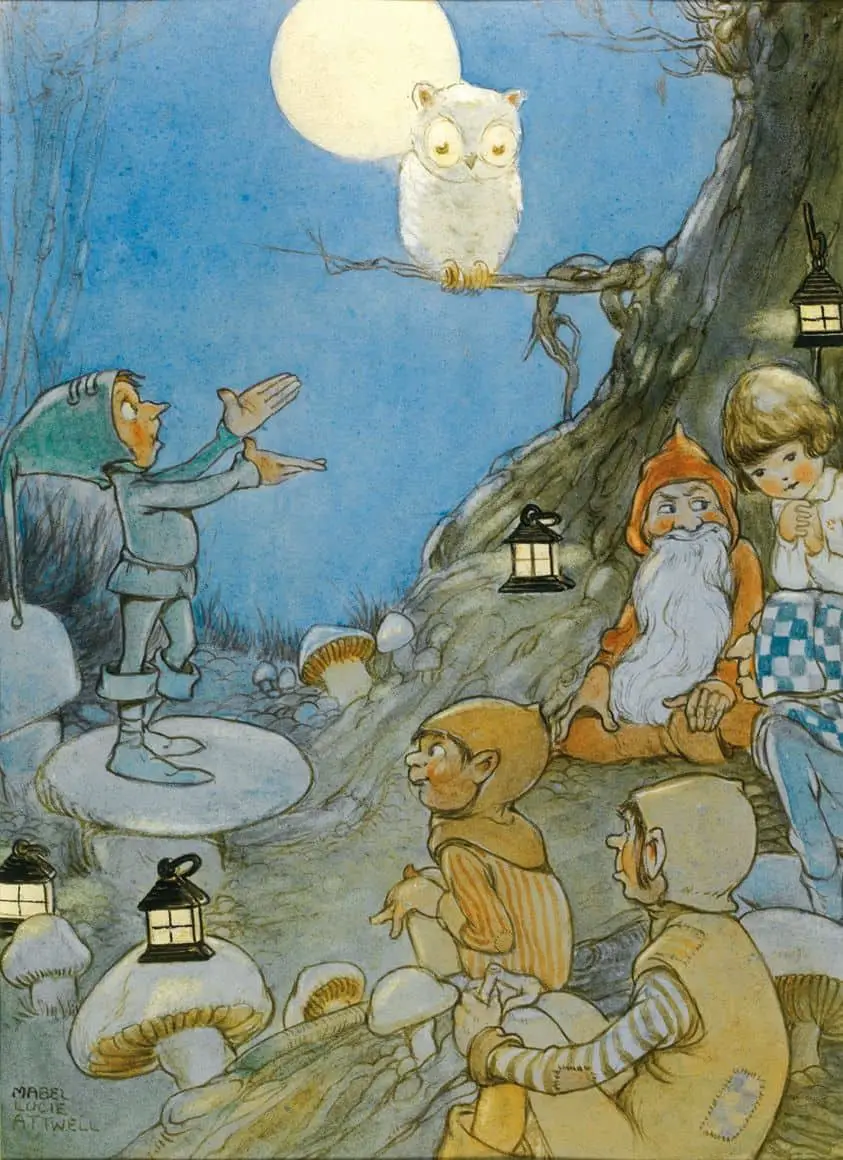

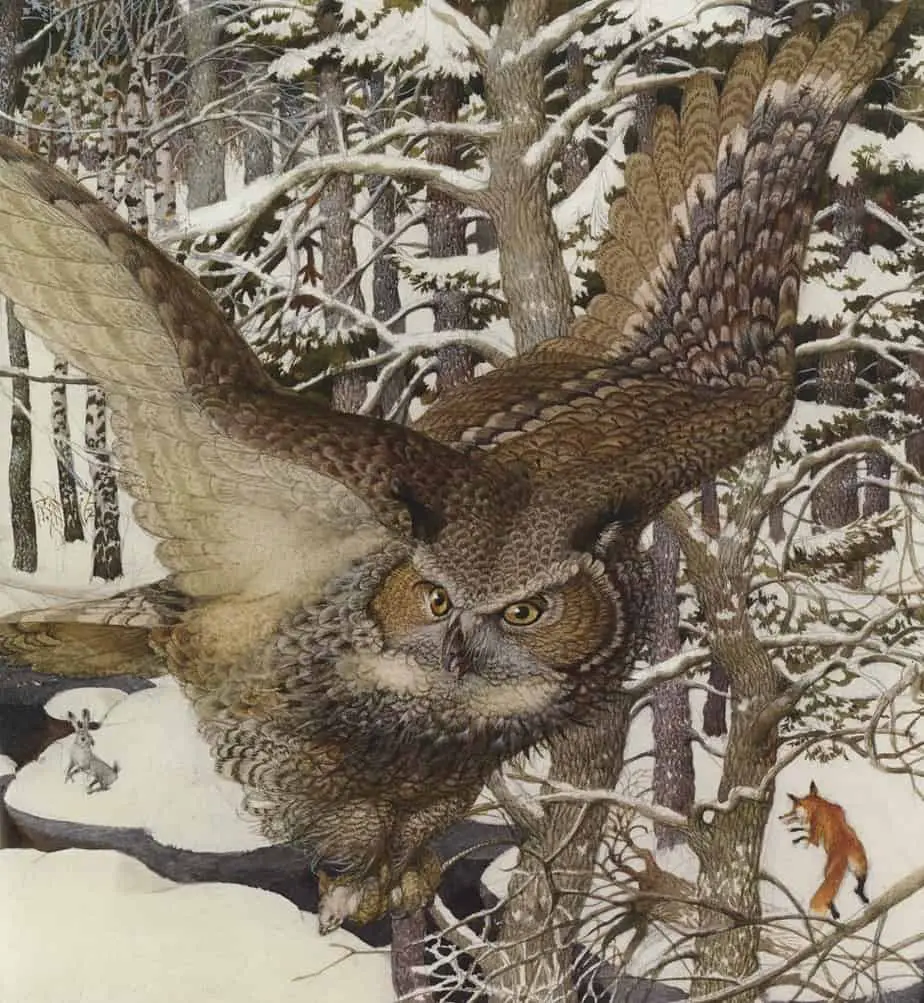

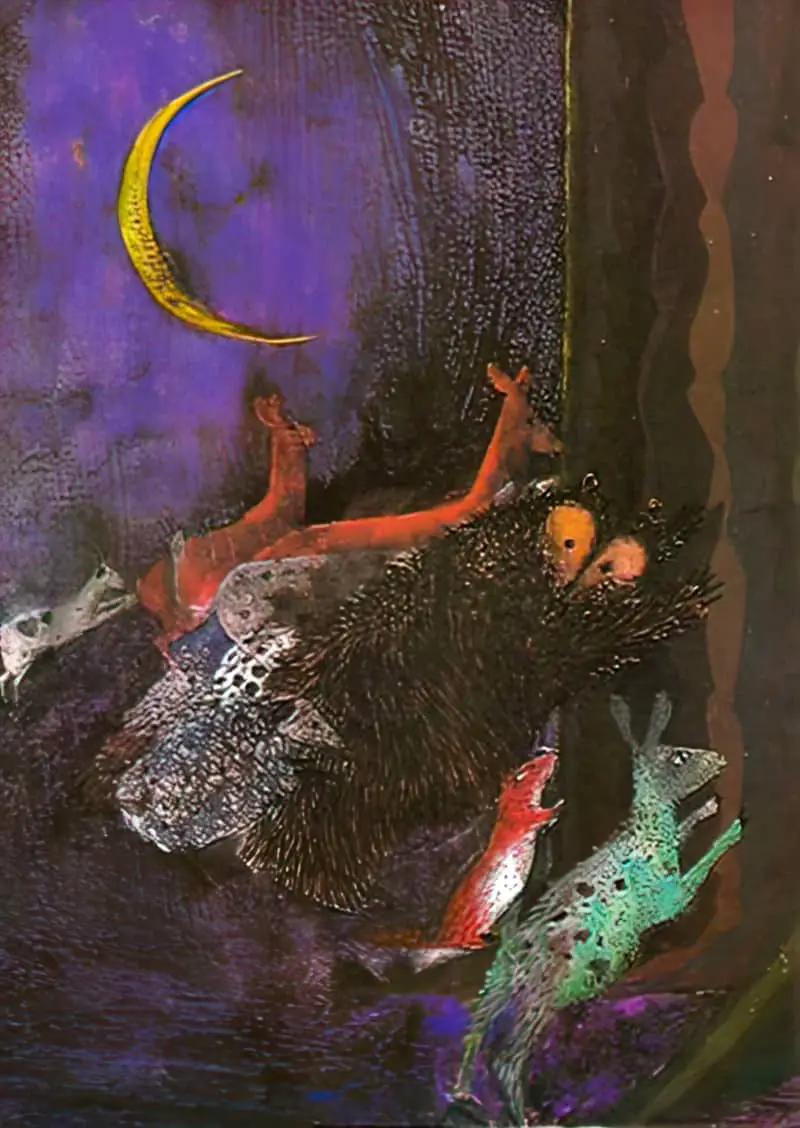

- ARENA — The little raccoon himself is stuck inside, but the illustrations offer the readers a view expanded to the most interesting part of the forest, where creatures come together to play at the magical time of the night, when the moon is full.

- MANMADE SPACES — They live in a forest where the animals have access to human technologies but there are no humans in sight.

- NATURAL SETTINGS — The utopian forest.

- WEATHER — The weather is steady and clear. No threat at all in this particular Arcadia.

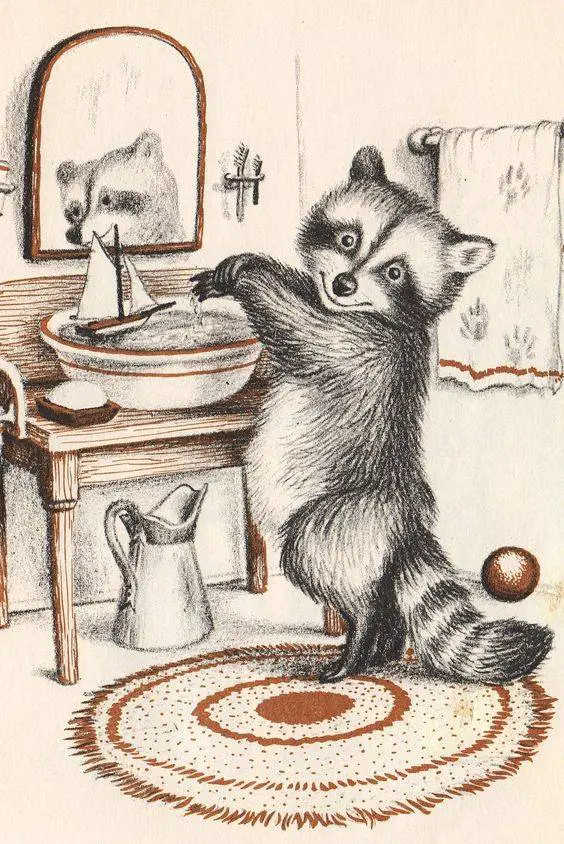

- TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — Although the main character is a racooon, and although he lives in a tree, the technology inside the tree is that of a modern human home, with tables, rolling pins, a bathroom and everything. However, the bathroom is not plumbed. This home is more typical of turn of the century home technologies. As is common even in picture books today, Garth Williams has been inspired by homes of an earlier era. (Probably those of his own childhood.) USB cords, flatscreen TVs, trampolines with safety nets and people using phones are much more common in real life than they are in modern picture books, so picture book anachronism endures.

- LEVEL OF CONFLICT — The level of conflict in a Margaret Wise Brown picture book is very low. The baddies who look like baddies simply exist. They’re not baddies at all. They’re simply populating the landscape (ie. the owl).

- THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — This refers to the land which lives inside the main character. The imaginative landscape, the difference between what is real in the veridical world of the story and how a character perceives it — never exactly as it is, but rather influenced by their own preconceptions, biases, desires and personal histories. In a Wise Brown story this is very interesting. The little raccoon has built up in his head what he might find outside. Kids do this. I have such vivid recollections of doing this myself that I wrote and illustrated my own book about the difference between hopes and realities after darkness falls. But in this picture book, for much younger readers, we can assume that he will find the fun he expects outside. (We are shown a spread.)

SHORTCOMING

STORY STRUCTURE OF WAIT TILL THE MOON IS FULL

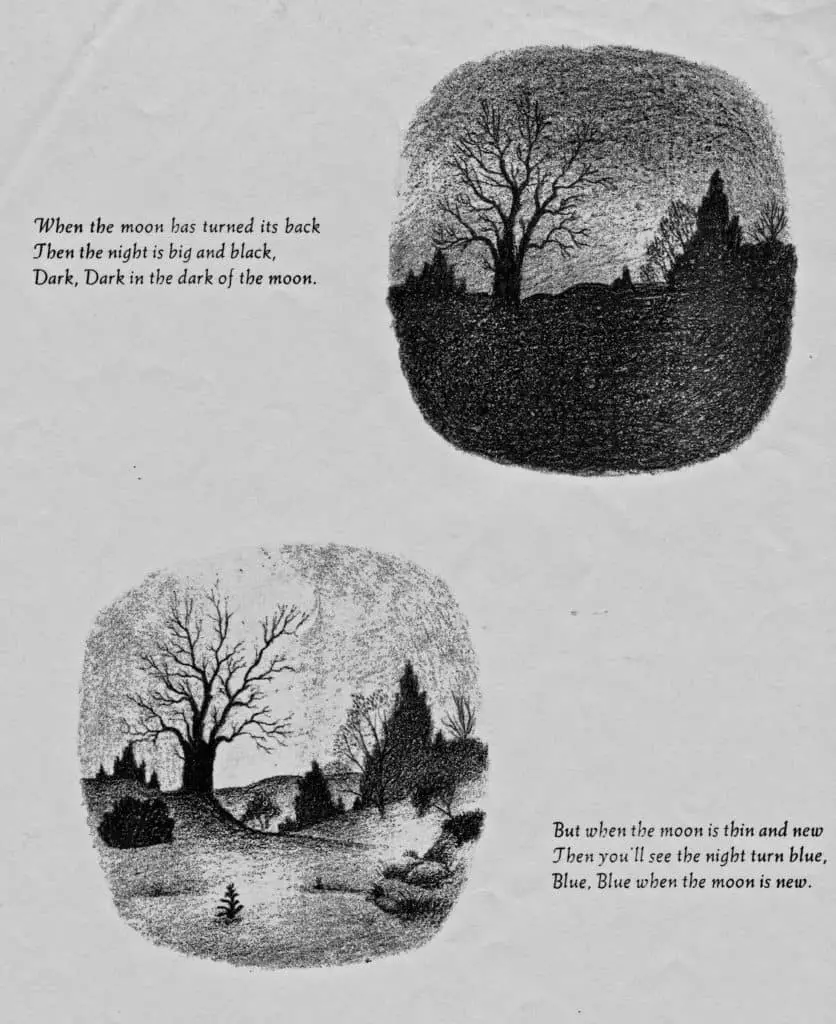

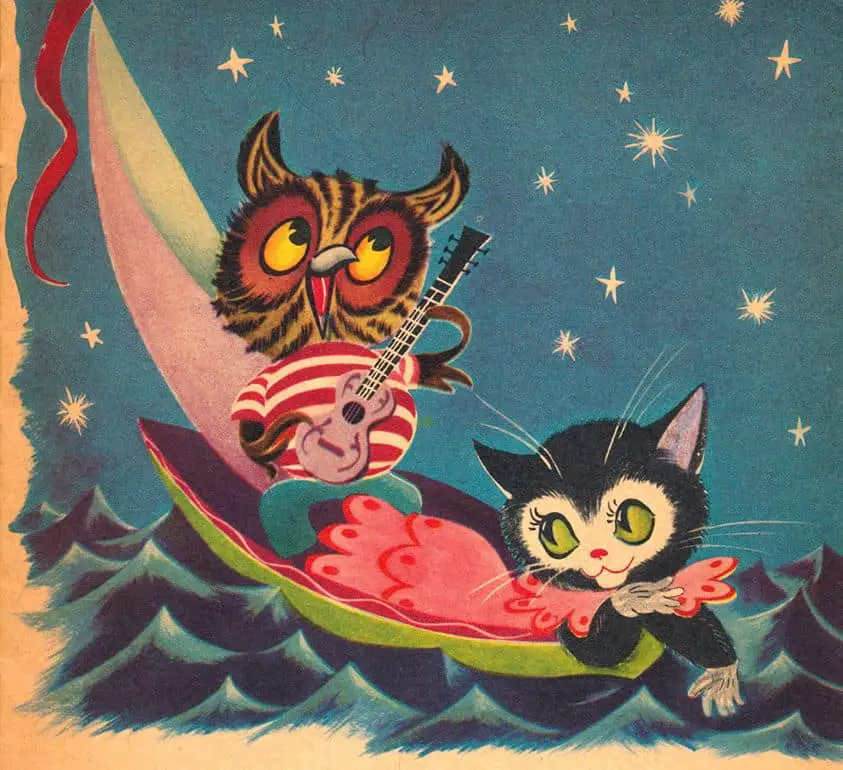

The carnivalesque part of the story is the section that reads like a poem. Wise Brown’s version of carnivalesque is not to simply ‘have fun making messes’ and doing things you wouldn’t be allowed to do under adult supervision, as it plays out in, say, in the picture books of Dr Seuss or Ludwig Bemelmans (Madeline). The carnivalesque part of a Wise Brown story is meditative, and in the case of Wait Till The Moon Is Full focuses on the reptition of colour, linking it to the symbolism and magic of the moon, which is highly symbolic across all types of story. (Wise Brown was clearly interested in the moon (see Goodnight Moon.)

PARATEXT

Once upon a time in the dark of the moon there was a little raccoon…

From the beloved author of such classics as Goodnight Moon and The Runaway Bunny, Margaret Wise Brown, and renowned children’s book illustrator Garth Williams comes the story of a curious little raccoon who wants to see the night.

But his mother says, “Wait. Wait till the moon is full.” So the little raccoon waits and wonders until, at last, the very special evening arrives…

modern marketing copy

SHORTCOMING

The raccoon is a child character and everything he does must be run past his mother. That’s his story worthy problem. As in a typical carnivalesque picture book, this main character has no moral shortcoming. He is the ‘every child’ (but extra cute in this case).

DESIRE

The little racoon has a very clear and overtly stated desire: He wants to see the night. This is a desire specific to children, and shows just how tuned in to children’s thinking Margaret Wise Brown was. Staying up past dark is no big deal to adults. But children don’t remember having seen it, and darkness therefore holds mystery and magical appeal.

OPPONENT

Whenever I asked my mother if I could stay up later the answer was always a flat no. But the response of the mother raccoon in this story only heightens the mystery of the night-time, sending a frisson of excitement down the young reader’s spine. She won’t let him go outside and see what he wants to see; she is thereby functioning as the story’s opposition. But she plays double duty; she is also his ally in fun. “Wait until the moon is full,” she says, uber-mysteriously.

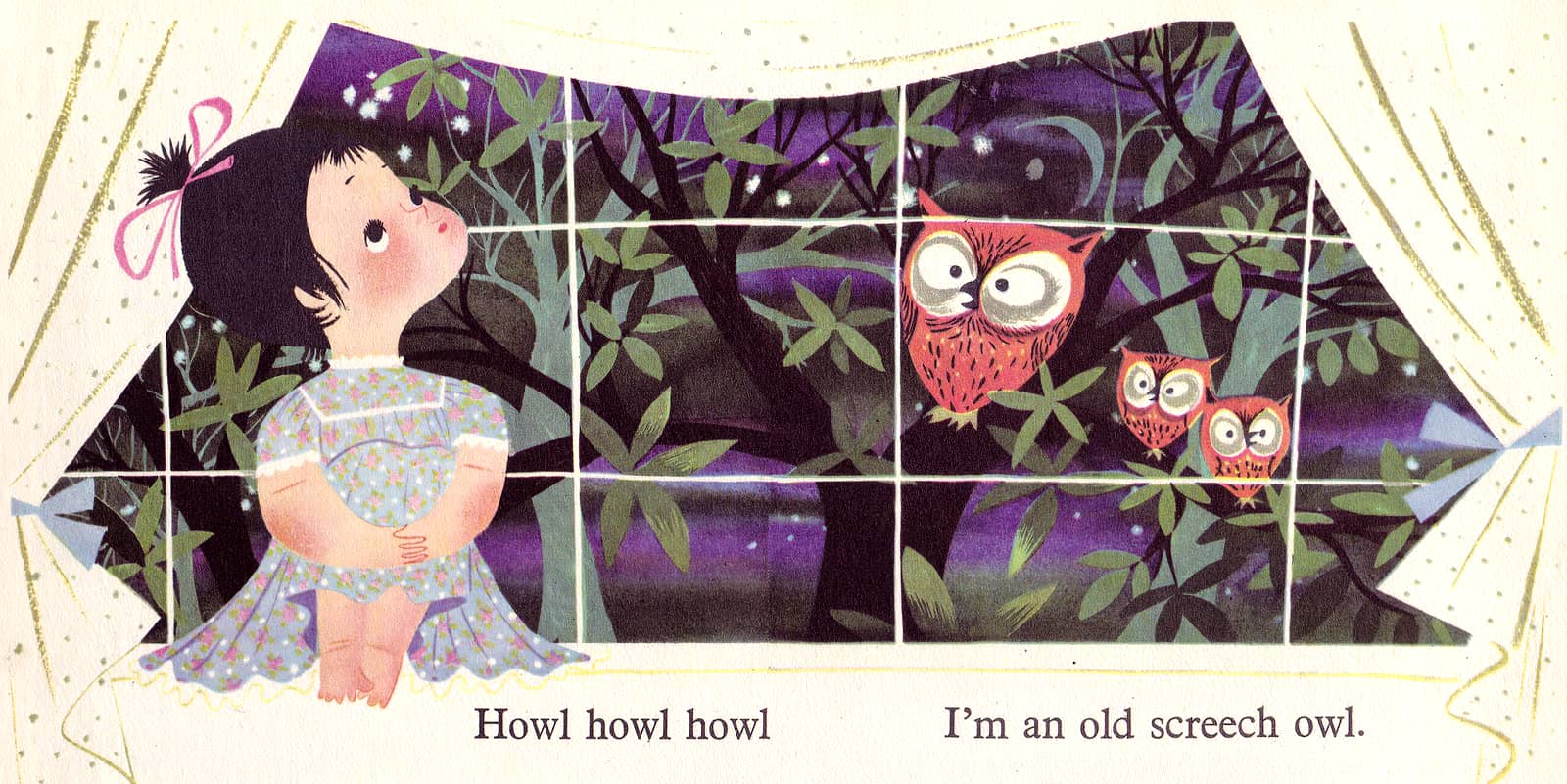

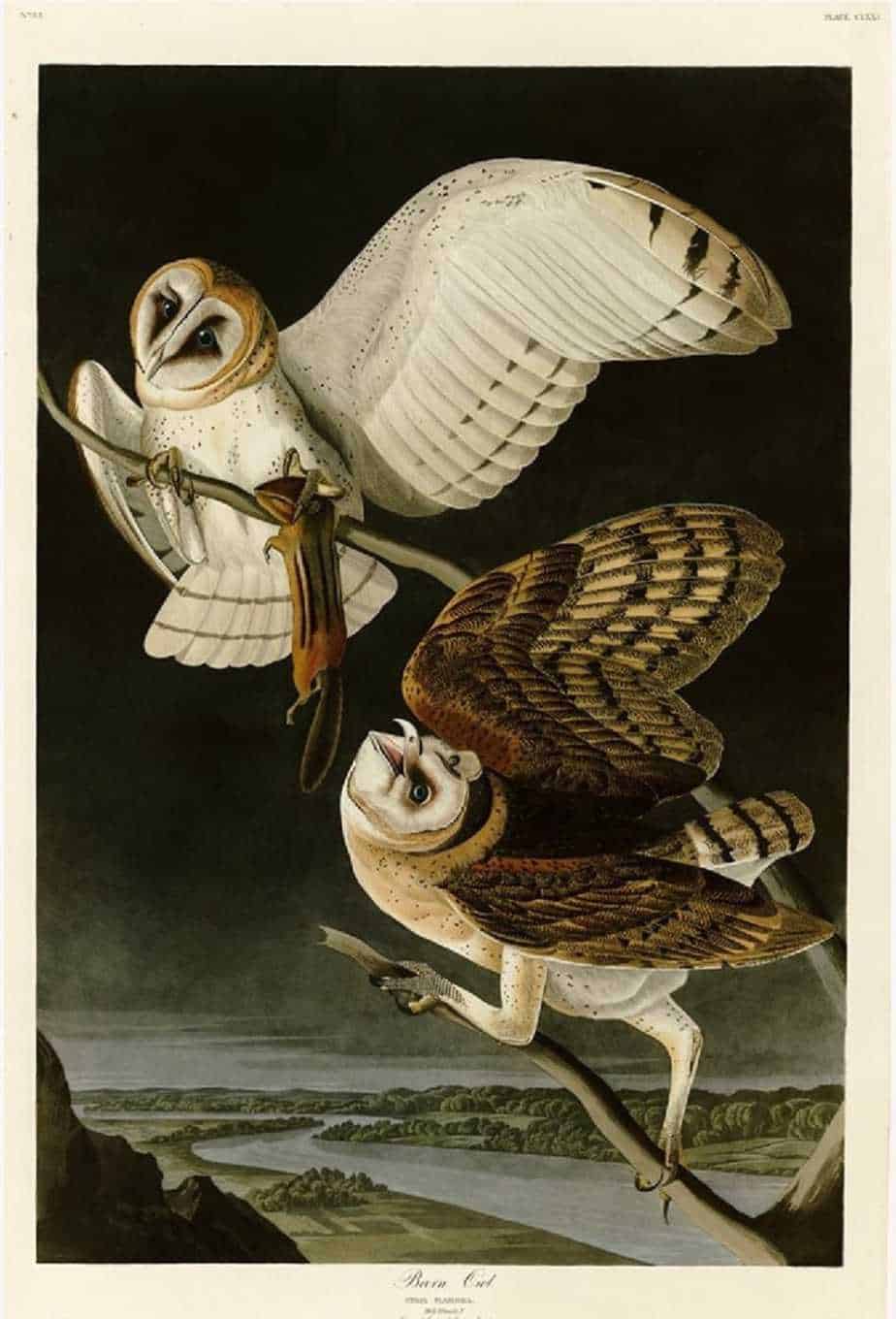

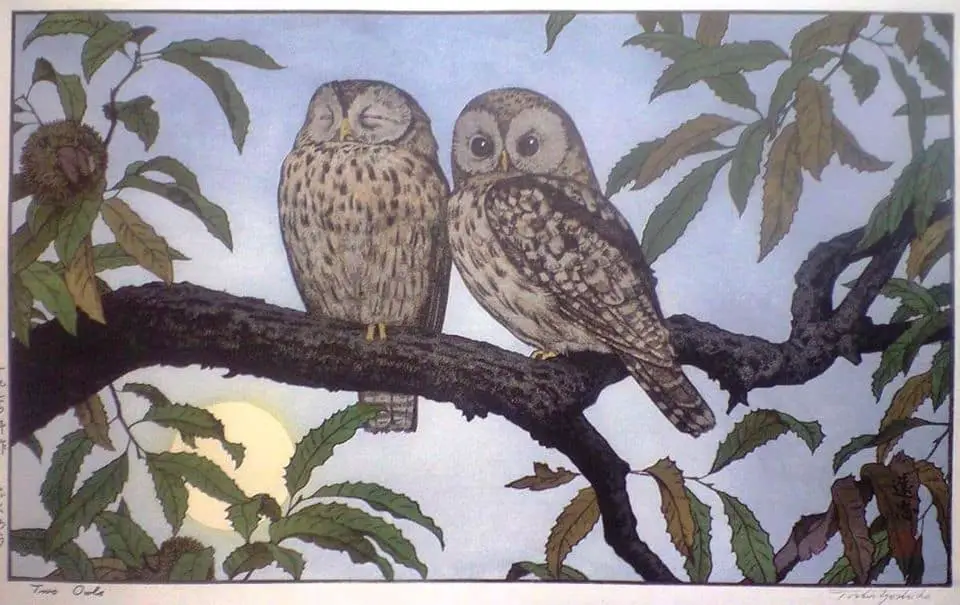

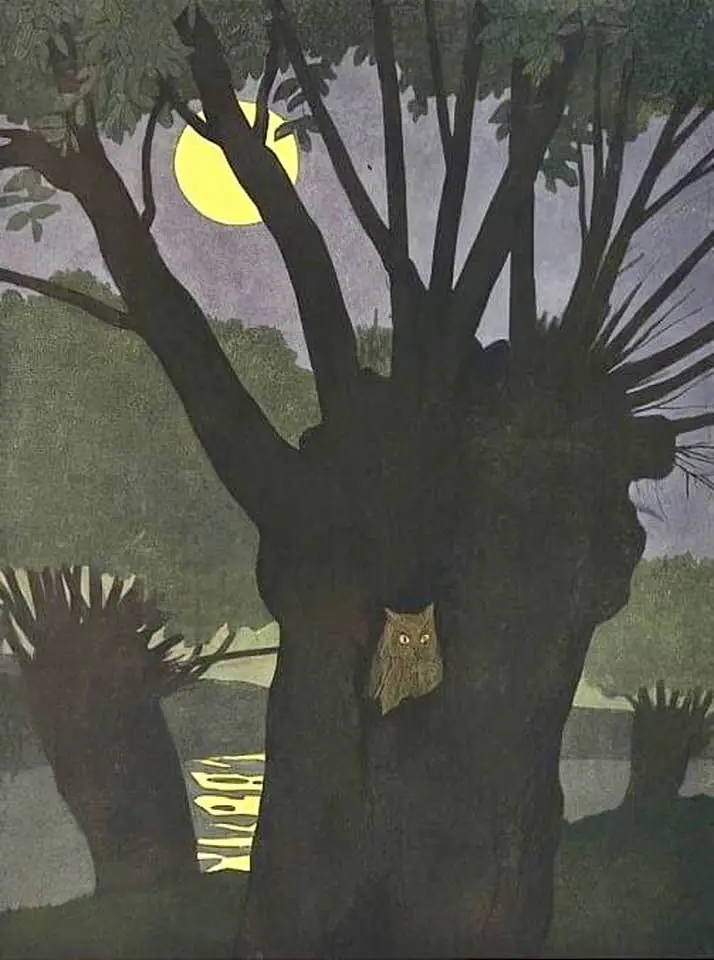

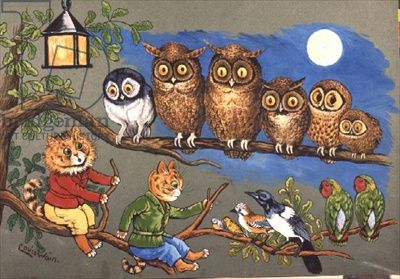

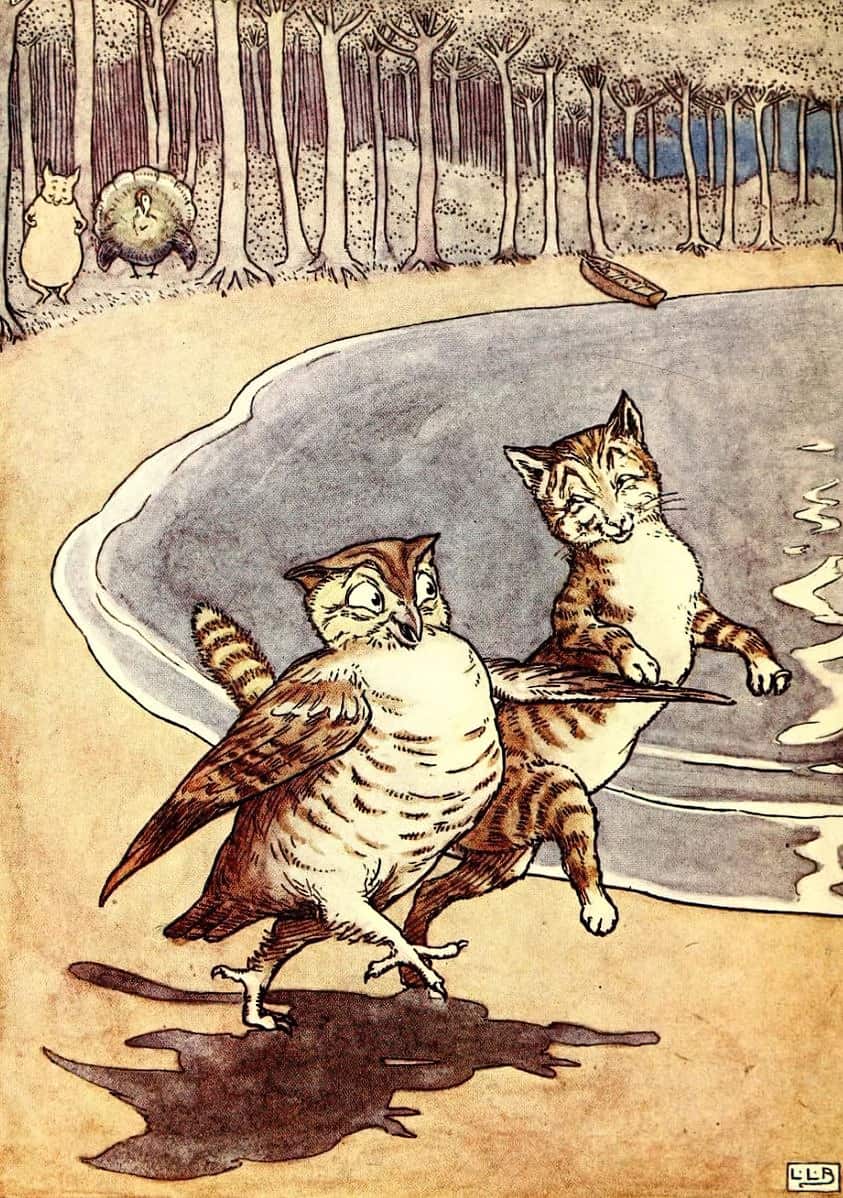

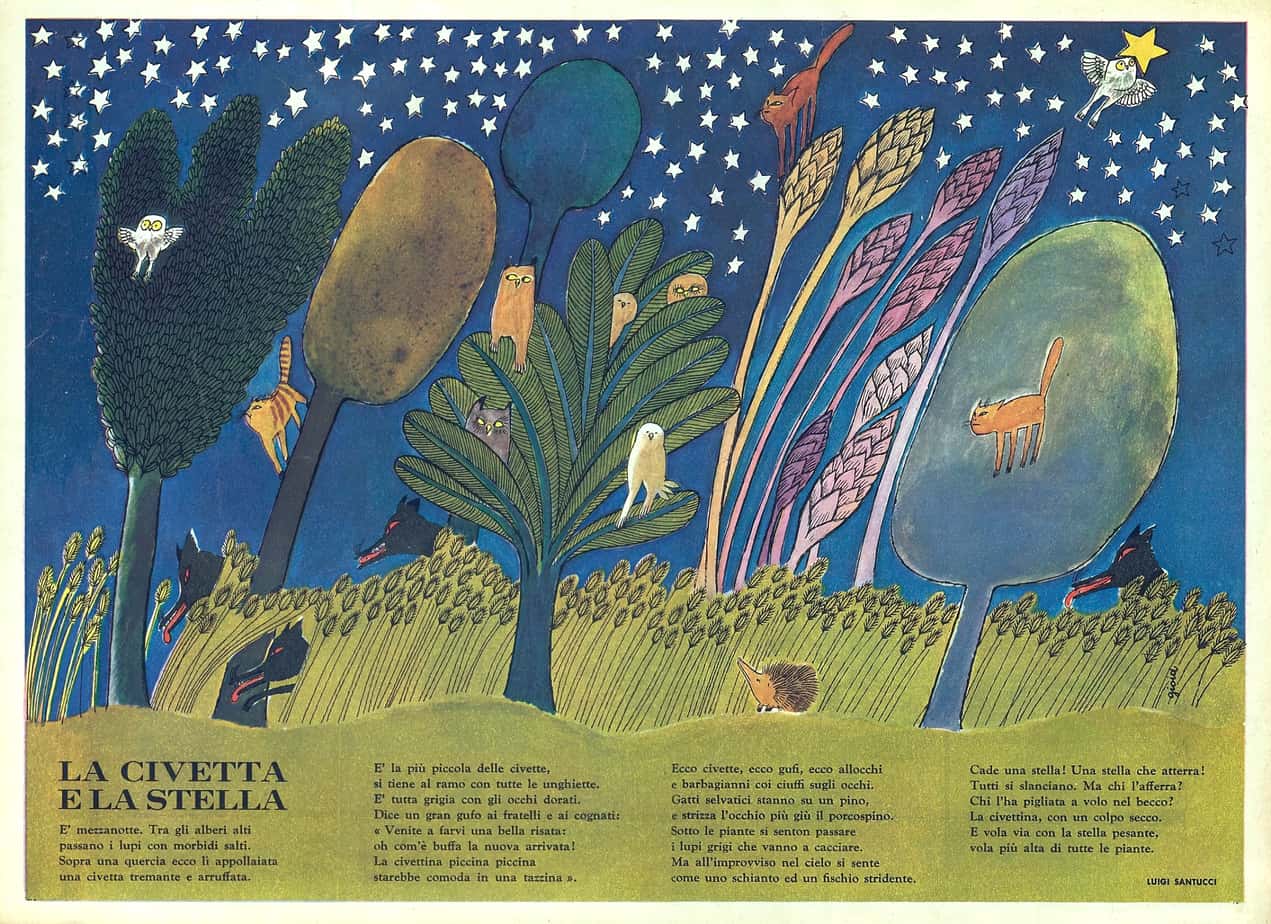

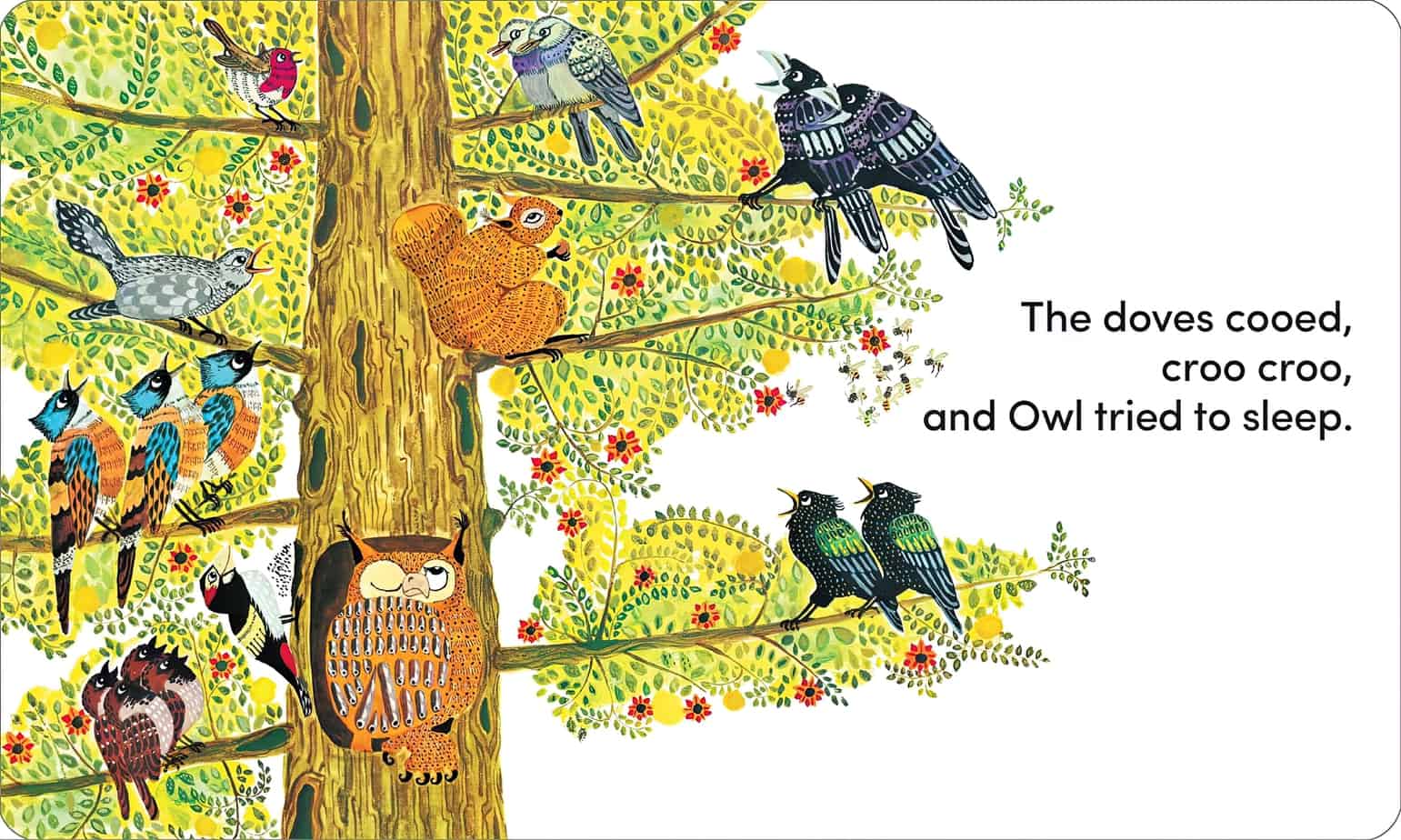

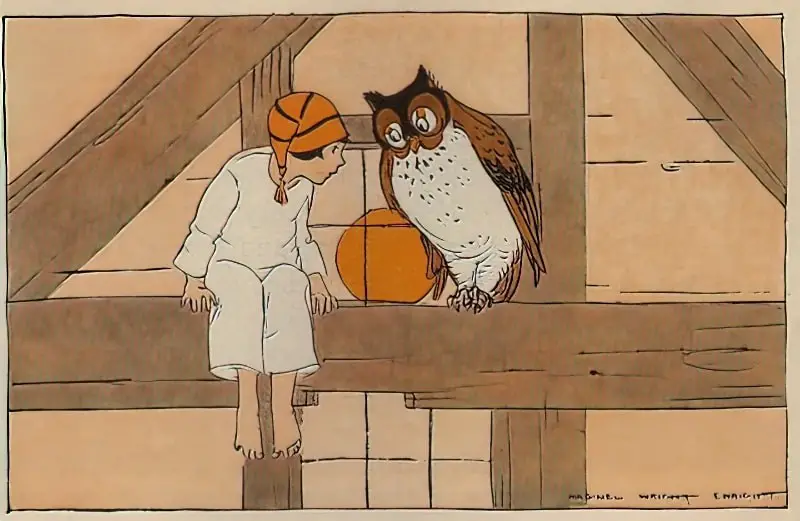

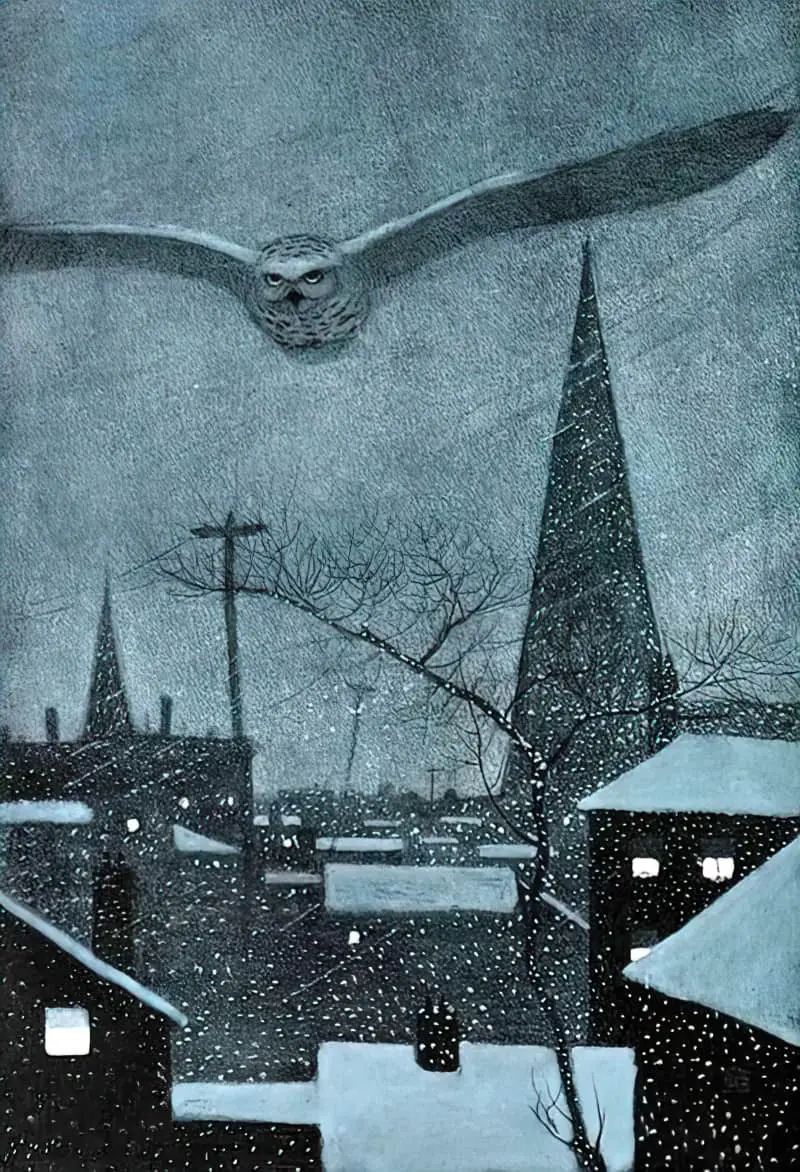

The little raccoon can hear the owl but cannot see it. However, Wise Brown and Williams make sure the young reader can see the owl, in a full page illustration in which the big-eyed owl looks right at us. Is this a Minotaur opponent, evil beyond redemption, evil for evil’s sake? Of course not. This is a Margaret Wise Brown picturebook. But this mysterious owl is the proxy, picture book proxy for such a villain. It is scary to hear something and not be able to see it.

Owls by Ben Shahn

PLAN

Like any young child anywhere, the extent of the raccoon’s ‘planning’ to get what he wants is to ask for it over and over again, hoping the answer will be different. This is annoying if you’re on the adult end of similar interactions with young children, but the repetition of asking works very well in a picture book. Repetition prolongs the story until the climax.

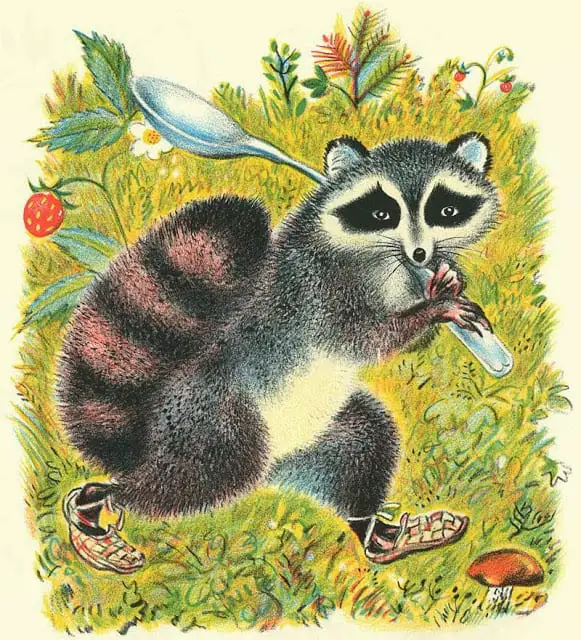

While waiting for the go-ahead to explore the wider world, he makes his own fun inside, clearly emulating events he imagines in the outside world. In this case, the basin is an ocean. (They need to replace their toothbrushes, by the way.)

THE BIG STRUGGLE

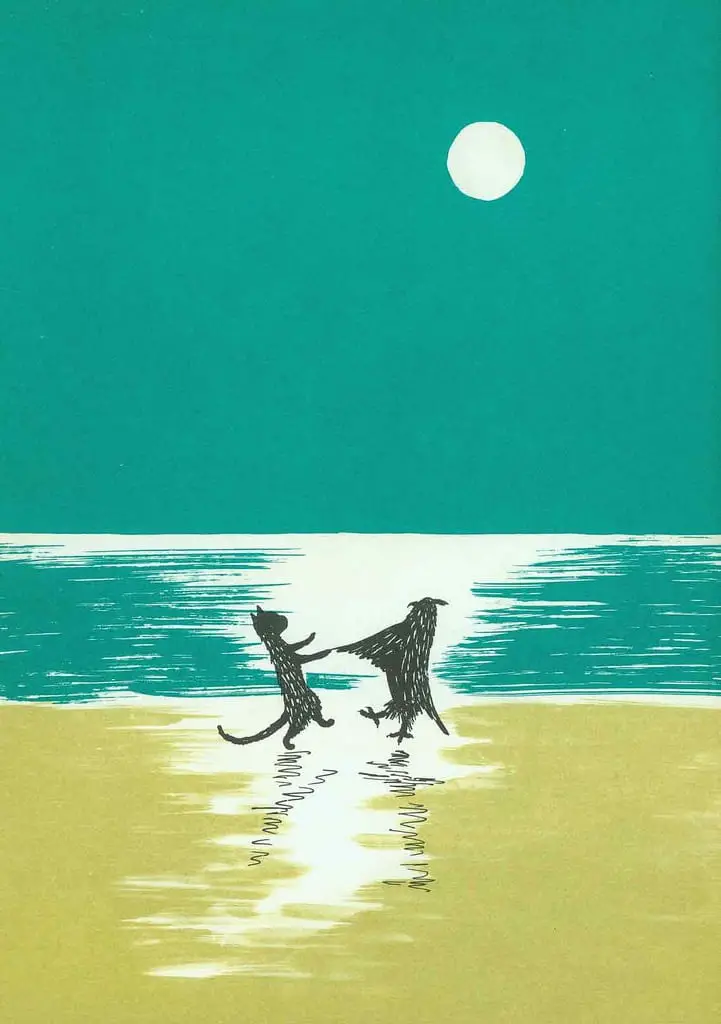

There’s a meditative carnivalesque element common across Margaret Wise Brown’s work, which otherwise defies description. Midway through this story the storytellers insert the scene of the night animals all having fun outside in the dark. This is crucial. A lesser storytelling team may not have realised that in order to sustain the young reader’s attention this teaser is necessary, especially with an ‘anticlimactic’ end.

The switch from the iterative to the singulative happens late in this story. Mostly that happens in a story after a brief set up of the main character’s daily situation, then launches into a one-time adventure, but in this case, the build-up relies upon the iterative treatment of time and finally, finally, the story switches to ‘one day’, at which point the mother recounts (in reverse order) everything that has been running through the little raccoon’s head.

This reverse order recount reminds me of the story structures of children’s stories such as The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson and The Enormous Crocodile by Roald Dahl. One half of the story introduces all the characters; the second half mirrors them, creating a mirror-like structure which feels cumulative and soothing. It’s as if the storyteller is ‘taking all the bad things back’ (safely).

Notice how the little raccoon is holding a baseball bat. I’m pretty sure it’s not purely to play baseball with. I’m sure I’m not meant to think he’s planning on whacking his mother with it should she not grant him his wish to go out into the night… I think it may also be Chekhov’s toy gun. He’s using it as a just-in-case weapon.

ANAGNORISIS

In a Margaret Wise Brown picture book, this part of the story is muted. Wise Brown was part of the early movement in creating stories for children which avoided didacticism, and she did avoid it entirely. I’d say most modern picture books are more didactic than Wise Brown picture books were, though it takes a different form, of course.

We don’t follow the little raccoon as he goes out the door.

NEW SITUATION

The final illustration shows the little raccoon ascending the stairs, presumbly because they live underground. This mirrors the child reader’s experience, who may well be ascending the stairs, but to go to bed, not out into the world. Less commonly, some child readers will live in basements. The ascending staircase is nonetheless symbolic of the little raccoon’s stepping ‘up’ into the adult world of night-time.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

The reader has seen the animals playing in darkness so we can assume that now the little raccoon will see that, too. All through this story, the reader has been shown illustrations that the little racoon has not, though I doubt the youngest of readers will realise that. (It doesn’t matter that they don’t.)

This picture book is another example of unusual story structure. Margaret Wise Brown understood storytelling to the point where she could do with it as she pleased. In this case, she brought the ending forward to the middle of the story.

Why? That’s the reallty interesting part, and is what I admire about this story. There is now an opportunity for child and adult co-reader to look out the window at the night-time together. This links the story world to the real world, and affords the story its resonance.

RESONANCE

I suspect this story influenced later picture books such as Can’t You Sleep, Little Bear? by Martin Waddell (2013). I personally find Waddell’s book irritating, and it’s to do with my thoughts on parenting and getting kids to sleep. (If you reward someone everytime they get out of bed, they’ll keep getting out of bed.) However, Margaret Wise Brown’s raccoon mother doesn’t have that effect on me. She’s more in line with my idea of what social media calls a ‘fun mum’, firmly ensuring the little raccoon is cared for and well-rested, but also joining him in his imaginative play around the night-time and all that it promises, granting him freedom only when it’s safe.

RACCOONS