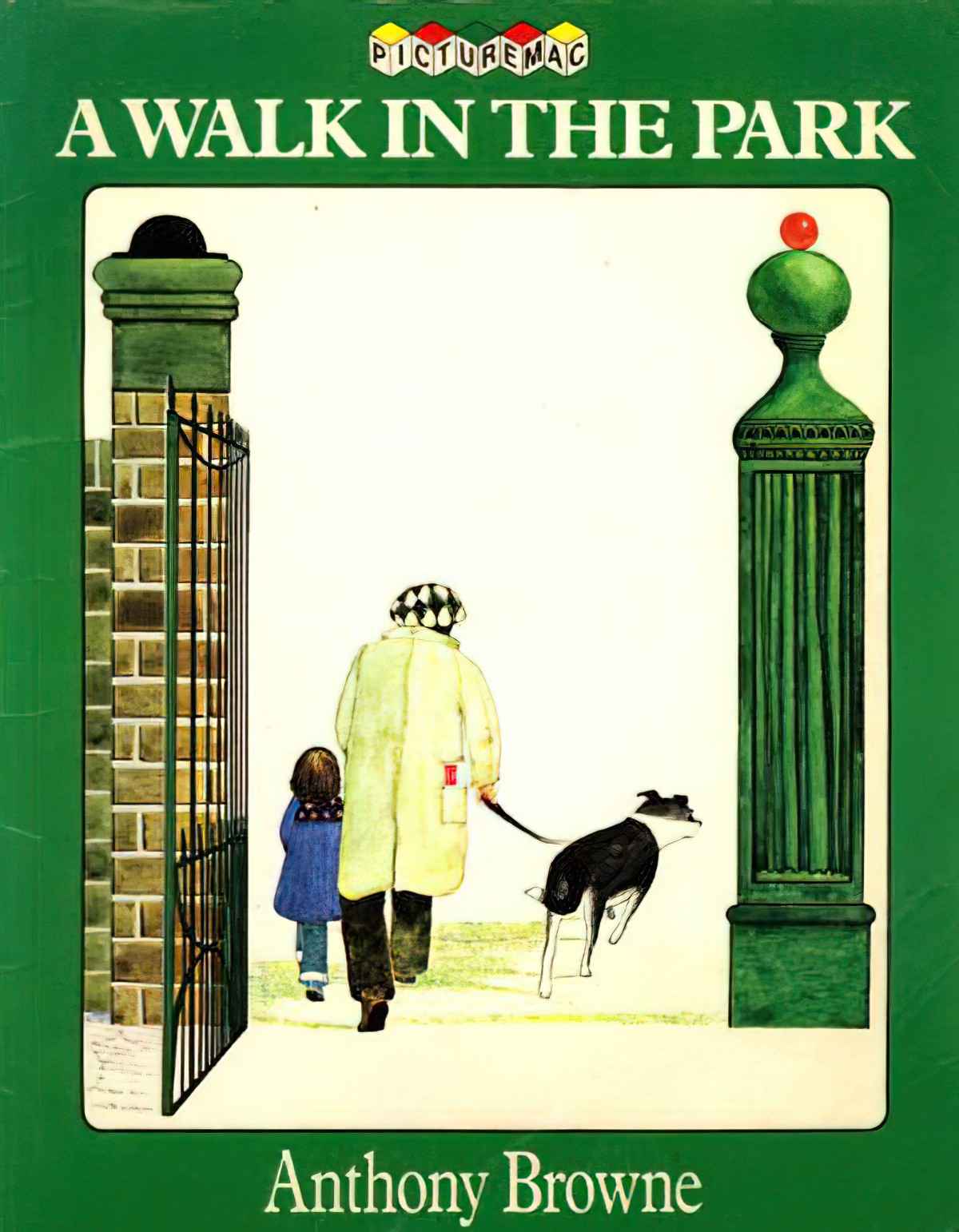

Have you ever wanted to go back and redo old work? A Walk In The Park is one of Anthony Browne’s earliest picture books — his second published after Through The Magic Mirror. Twenty years later (in 1998), Browne decided to redo this book in Postmodern style. Now it is called Voices In The Park. In the earlier title, postmodern elements are nascently evident. Look closely and you’ll find minor elements that don’t quite fit the scene. The earlier version has a single voice. The updated book contains four separate voices in first person and is far more surreal.

Surrealism

Like Belgian surrealist artist, Rene Magritte, Browne uses the same symbol over and over to convey meaning.

‘Surreal‘ in everyday English means ‘I didn’t understand it’. But in relation to works of art, surreal means literally ‘over and above’, ‘more’. The word refers to art which makes use of paradoxes, riddles and allusions. Something in the work is ‘superimposed’ over the naïve reading. ‘Surreal’ means the viewer must contribute to derive meaning.

Surrealists put disparate objects together. In doing so, they help their audience to see objects we usually take for granted in a new way. The word for this is ‘defamiliarisation‘.

I use surrealism a lot is because I was very affected by surrealist paintings when I was young. I also believe children see through surrealist eyes: they are seeing the world for the first time. When they see an everyday object for the first time, it can be exciting and mysterious and new.

Anthony Browne from from the Teaching Books interview

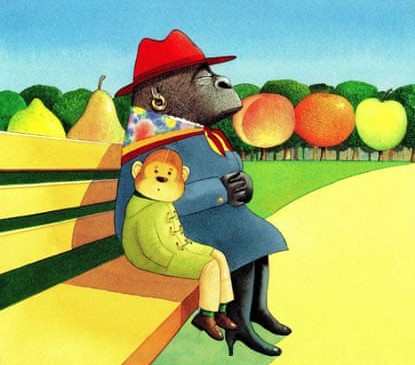

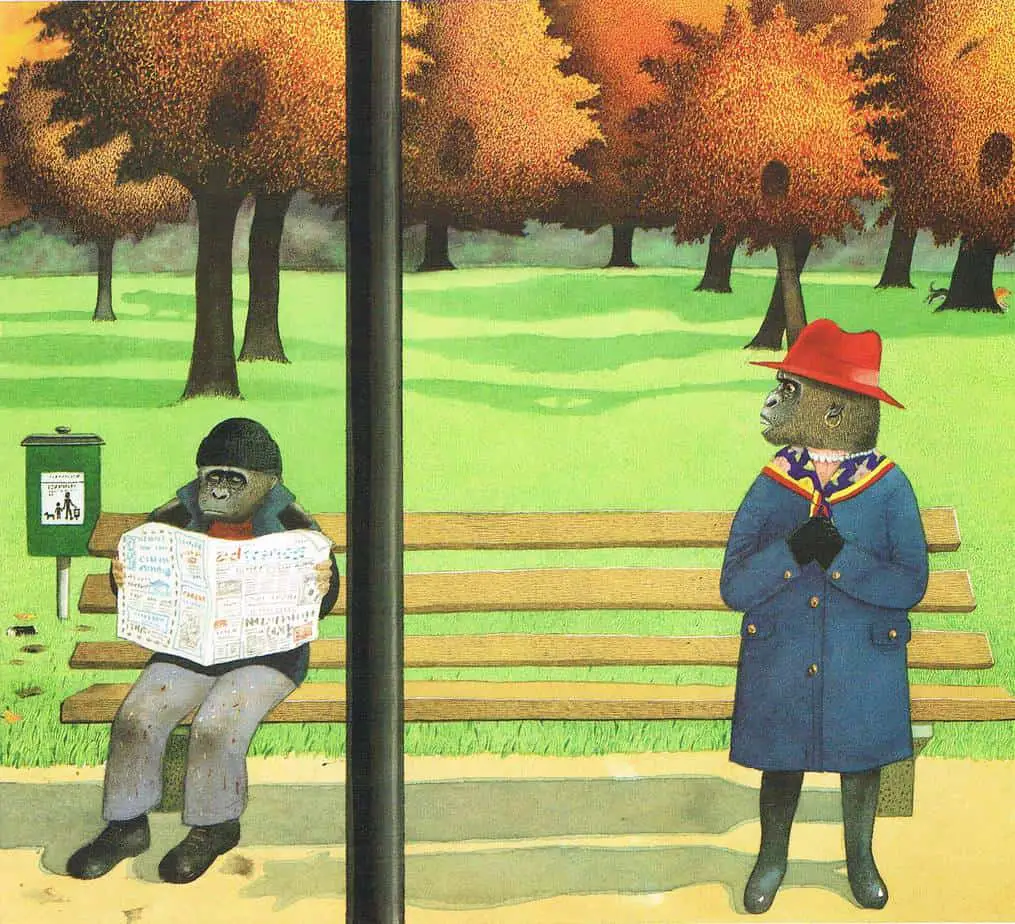

Let’s take a close look at Browne’s illustrations. The seasons are different for different characters, even though it’s the same bench.

(There are a couple of characters but at first we see them from behind.)

The friendship between the children is blooming, but Browne highlights the difference in class between the two families. There’s the very working class Mr Smith (indicated by clothing, speech, home), and the wealthy status of Mrs Smith.

Metafictive Devices

Metafiction is a type of fiction which draws attention to its status as a work of art. We know as readers that we’re being played with as a reader. But we go along with it. The update is deliberately staged and artificial.

The animals still have an animalness about them even though they’re obviously meant to be humans. We associate gorillas with ‘big, tough, strong’, therefore ‘big, tough, strong’ nature of humans which then stand for teachers, adults, big people, bullies.

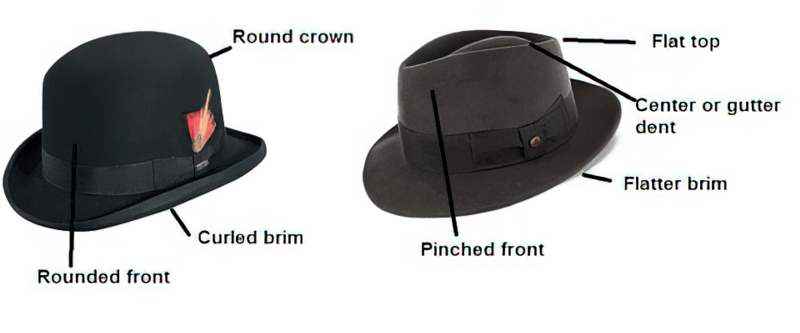

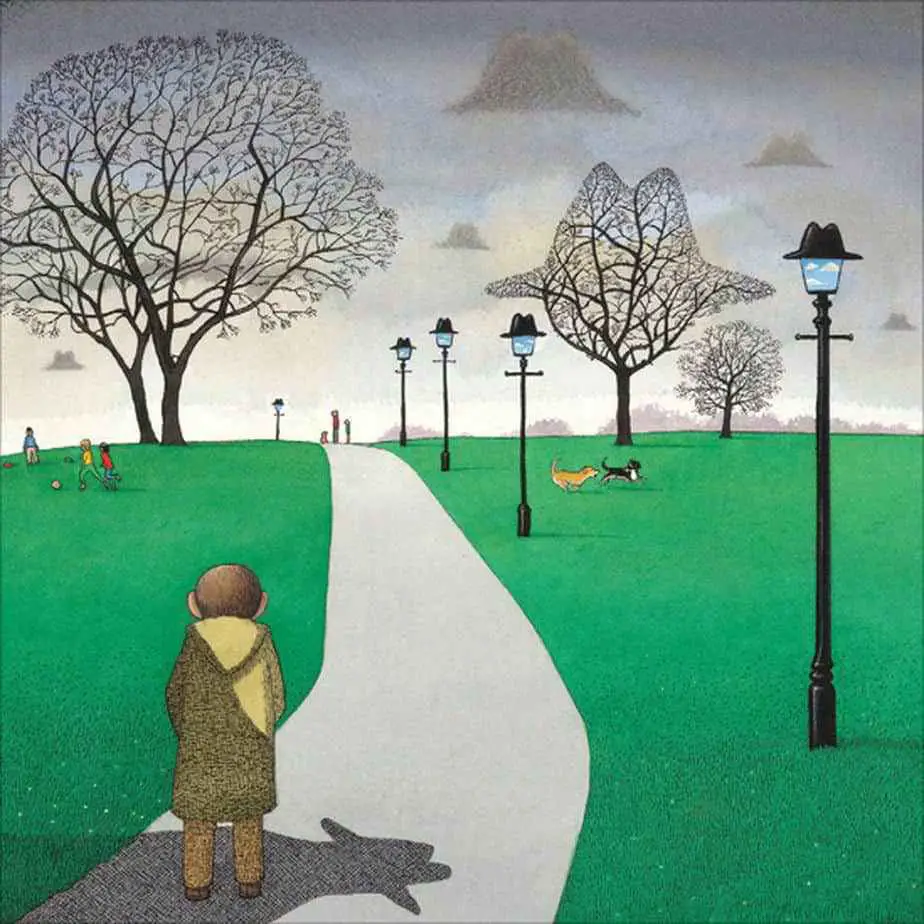

Look at the illustrations and you’ll find bowler hats in trees and so on. What do hats symbolise in this particular story? Hats typically function as a mask — something you wear to present your omote to the world, hiding your ura (to use Japanese terms). The omote is your public self; the ura your private self.

Hats also denote socioeconomic status. In this case, the hats are ‘bowler’, and therefore stand for a particular social class. The boy is being trained by his mother to present a certain, repressed side of himself to the world. Instead of running around like his labrador, he sits sedately by his mother’s side. Eventually the repressive bowler hats disappear from his view as the girl, Smudge, brings out his ura.

SETTING OF VOICES IN THE PARK

This story appears to be set in England, though I’ve never seen a big English park as deserted as this one. This park is a representation of the characters’ inner states, in which no one is truly connected to the others. (See also: Loneliness in Art and Storytelling.)

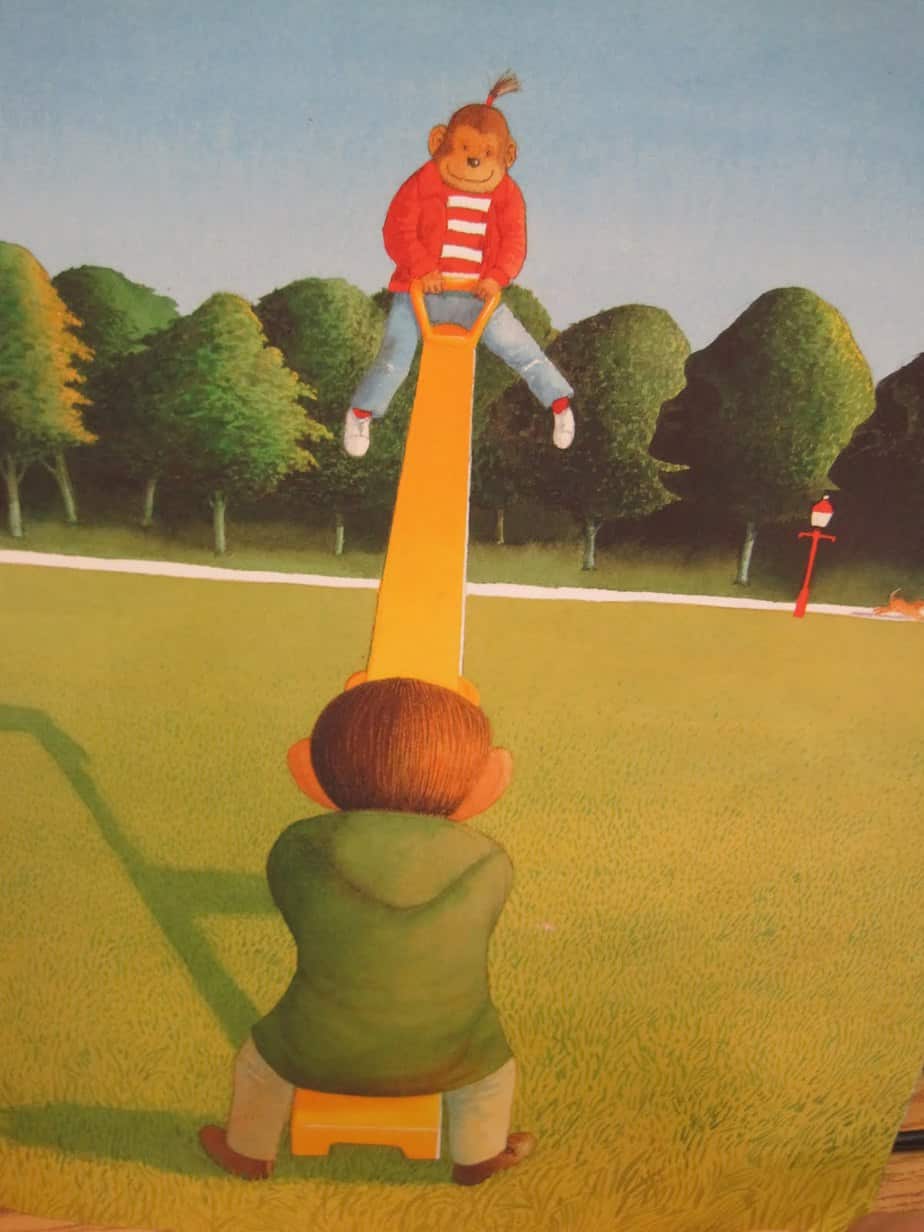

The composition tends to symmetrical. Clearly the symmetry serves to emphasise the inherent equality between human beings; in this park, outside the individuating arena of their homes, everyone is on the same level, literally.

The exception to ‘all on one level’ is the see-saw scene, but the nature of a see-saw is that people take turns being up and down. Effectively, this is an egalitarian metaphor. In this image, the poor girl is higher than the rich boy. Life can thrust us out of riches (more frequently than it thrusts us into them.) Socioeconomic circumstance should be considered, like life, like health, a temporary state which can change suddenly at any time.

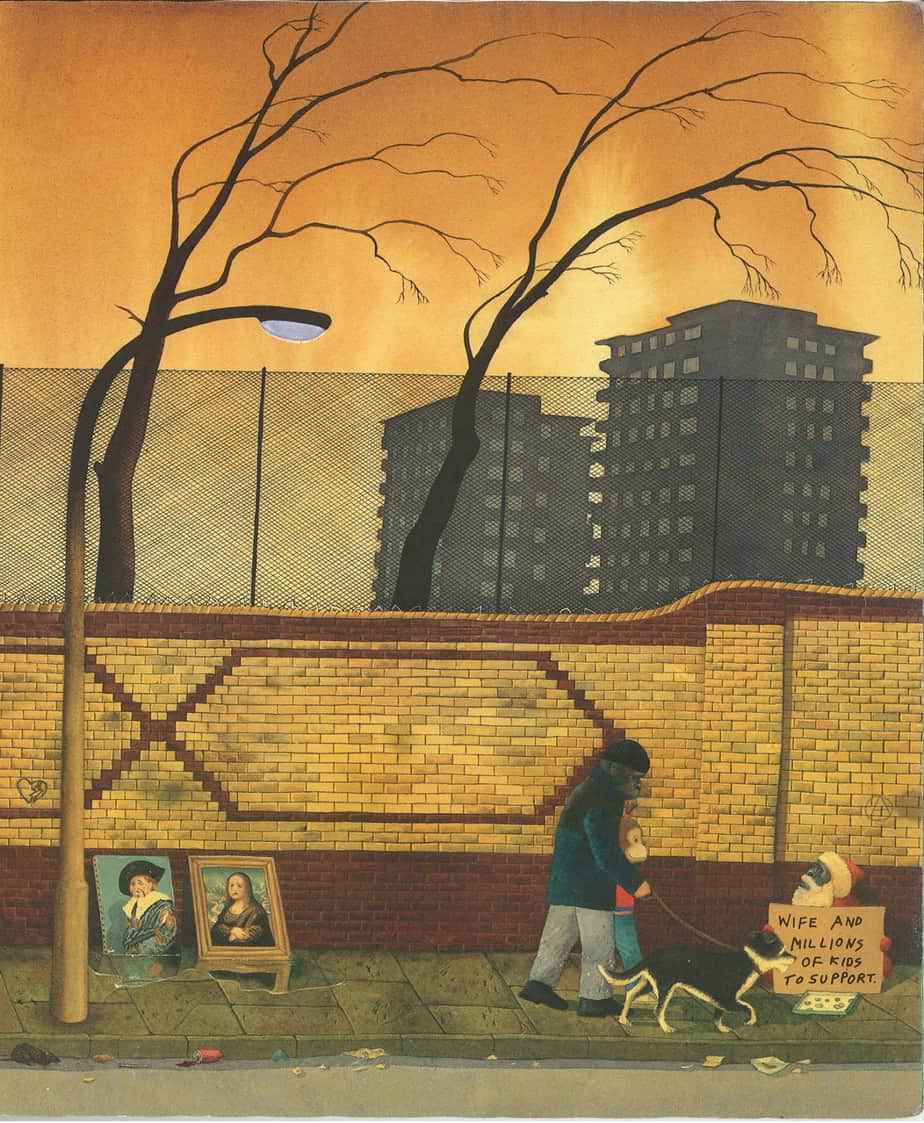

As father and son walk to the park, they are downcast. The father “needed to get out of the house”. They live in an economically destitute area, and pass a man sitting on the street asking for money. “Millions of kids”? The kids that Santa gives gifts to? There are many millions of poor children in this world.

Notice the ‘a’ in the circle etched into the wall behind him: A symbol for anarchy since the 1970s. Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is sceptical of authority and rejects all involuntary, coercive forms of hierarchy. In this sense, Voices In The Park has an anarchist message. Anarchism also calls for the abolition of the state, which it holds to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful.

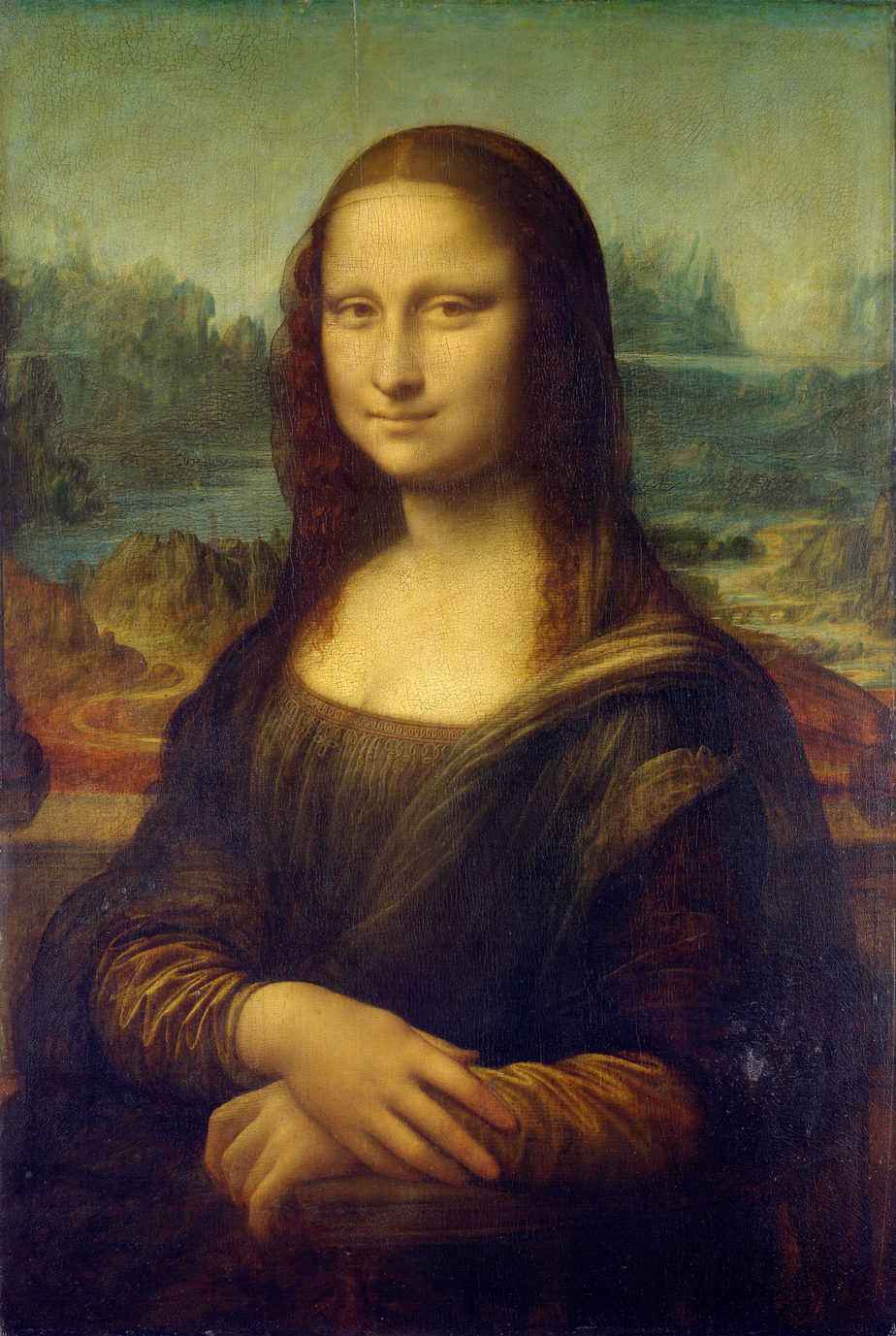

The Laughing (actually Sad) Cavalier and a weeping Mona Lisa sit in a puddle of ‘tears’.

Even the trees in the illustration below reflect the hunched posture of this father and daughter on the way to the park.

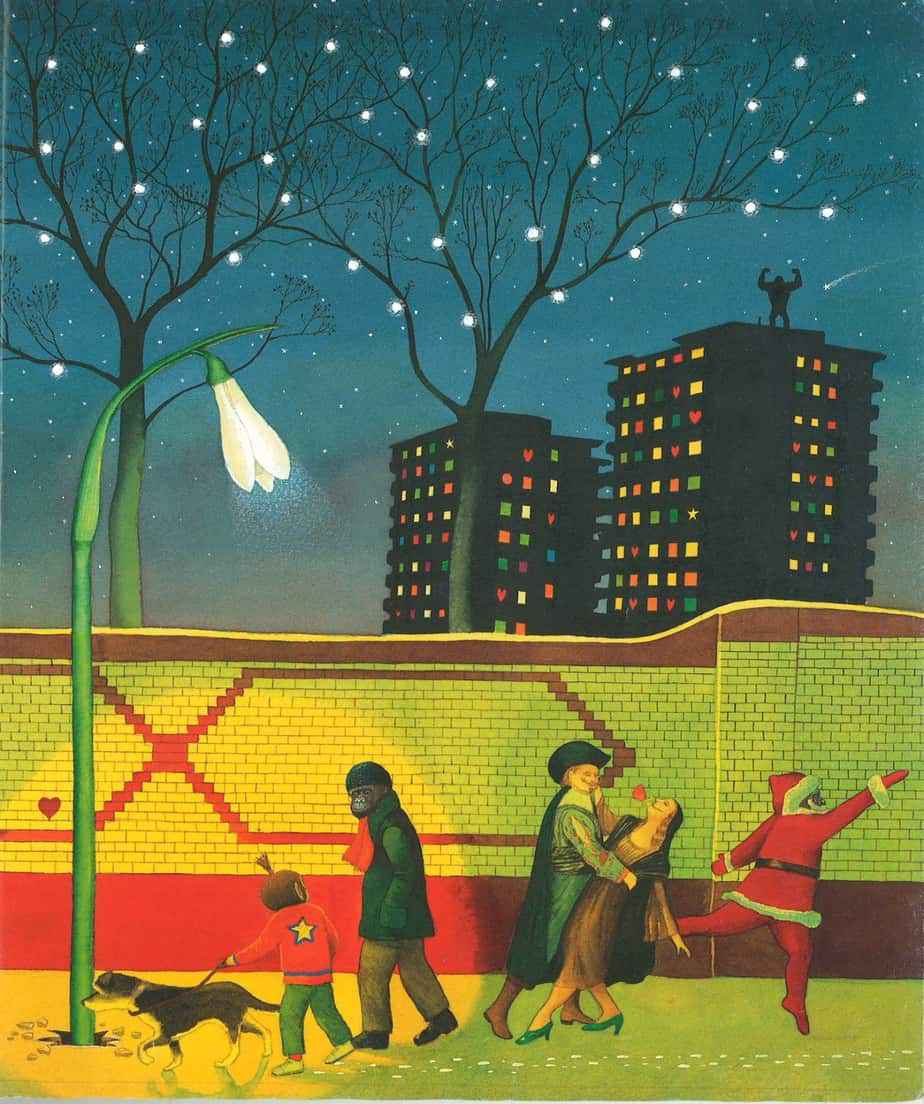

Importantly, the story is atemporal by design. Is this sky one of the evening, morning? We don’t know. Once the characters assemble at the park, the seasons keep changing according to whose story it is. This makes use of the symbolism of seasons, of course, but also lends a universality to this story of humanity and hierarchy.

The father’s walk home will show his emotional state much improved, like the cheerful night before Christmas.

The symmetry of the composition of full bleed illustrations of this story contribute to general creepiness, much like paintings by Italian artist Alessandro Tofanelli.

STORY STRUCTURE OF VOICES IN THE PARK

Stories come in a variety of shapes. Most picture books have a linear storyline. The structure of Voices In The Park is rare. Impressionists have a word to describe it — ‘parallax‘. (Note, too, that some of the illustrations include Impressionist techniques, at least in comparison to Browne’s signature work — the spots of colour on the orange cover trees are a good example.)

In a parallactic story, the audience is offered more than one perspective of the same temporal event. In this example, we first have the perspective of a snobby, rich mother, next of an unemployed father, then of the rich woman’s son, and finally of the poor man’s daughter. Meanwhile, the dogs run around having carnivalesque fun in the background.

What is the reason for a parallactic plot structure? In literary parallax, the message is implicitly this: The truth does not exist. A person’s version of the truth depends on their perspective. This is a defining characteristic of the literary Impressionists. That said, I think Anthony Browne has used parallax to a different end in this instance. I believe he conveys an unambiguous message: Repression of children is bad; playing is good; friendship across socioeconomic boundaries is good. He uses parallax to avoid hitting readers over the head with this ‘message’. A strong message like that could easily seem didactic. When readers put pieces of a puzzle together for themselves, they are more likely to agree with the storyteller’s message, regarding it as self-evident.

Another way parallax sometimes works in picture books: Within the world of the story, the reader doesn’t know what is real and what is in the imagination. In stories for young children (especially carnivalesque ones) a child character’s adventure is probably happening entirely inside their own head. But for a child reader, it makes no difference whether a story happens within the mind or within the veridical world of the story. For children, there is no distinction between reality and imagination. The ultimate experience is the same.

PARATEXT

One day Smudge and Charles (two very different children) take walks to the park with their dogs, Albert and Victoria. The dogs race off and chase each other around the park, while Smudge and Charles become the best of friends. First published in 1977, this tale of friendship which is one of the first books by internationally acclaimed picture book creator, Anthony Browne is available again in paperback.

MARKETING COPY

SHORTCOMING

Stories in which an ensemble cast get an equal voice are generally stories about a society, and this is true in this case as well. One major weakness of our society is the class divide. There is of course much that can be said about that, and how economic stratification has a ruinous effect on us all, especially on poor people.

Anthony Browne has avoided making commentary on race by giving the humans the bodies of gorillas. This is one reason (among many) why illustrators/storytellers utilise animal bodies when telling stories about humans.

MRS SMYTHE

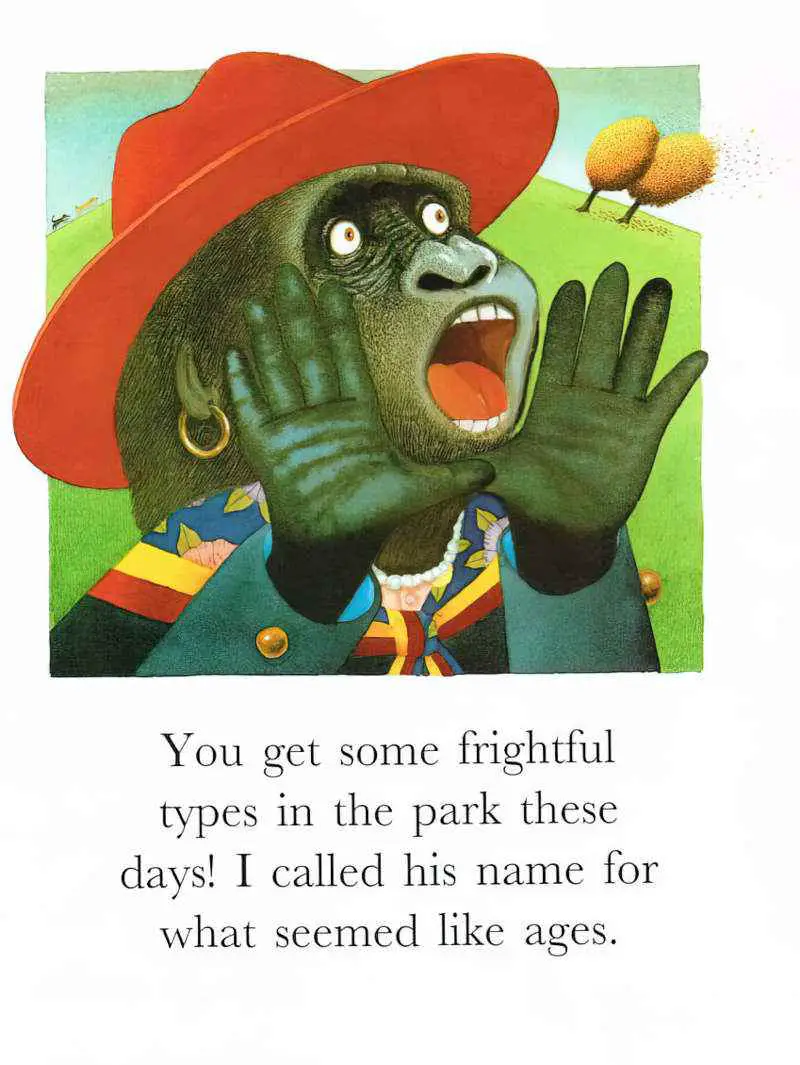

Anthony Browne has described Mrs Smythe as “dominant” and “militaristic” and explains that she loves her son but overprotects him. This is evident from what the girl says later, about how she won’t even let a dog smell her dog’s butt (something dogs don’t mind at all).

MR SMITH

The man has a status shortcoming rather than a moral one. He is good, but he is unemployed. Any modern economic system builds a certain amount of unemployment into its very mechanism. There is increasing voter awareness about how a certain level of Black (or in England, BAME) unemployment is built into economic systems. In America, ‘the Black unemployment rate has consistently been twice the white unemployment rate’. The system is designed to work like this.

How are the names symbolic? The homophonous names show that they are all equally human. ‘Smith’ is more common/popular than ‘Smythe’, suggesting some pretension on the part of the rich family.

There is some disagreement about the origins of the numerous variations of the name Smith. The addition of an e at the end of the name is sometimes considered an affectation, but may have arisen either as an attempt to spell smithy or as the Middle English adjectival form of smith, which would have been used in surnames based on location rather than occupation (in other words, for someone living near or at the smithy).

Wikipedia

(This is also probably a joke directed at himself, since the author/illustrator has a decorative ‘e’ at the end of Brown.)

CHARLES SMYTHE

Notice how the children are given different types of names. The rich boy’s name is the name of royalty, of public school educated white boys, typically. Charles is being acculturated into a patriarchal system in which he will enjoy power but also be repressed by its expectations. Below he literally and metaphorically stands in the shadow of the (bowler hat wearing) patriarchy. He already understands the gender hierarchy and that he is at the top of it. He is initially dismissive that he has to play with a girl, and then he accepts that she is good at using the play equipment. Note the distinction between sexism and misogyny: Charles may have had the sexism removed, but there’s no indication that he’ll be free of misogyny just because he’s learned girls can be good at things, too. (Sexism and misogyny are not the same — and the difference matters.)

SMUDGE SMITH

Smudge is clearly a nickname. The girl has dispensed with the formality of a legal name as she has dispensed with the natural reserve of adults, who have trouble making friends with other adults. Smudge also suggests a dirtiness, symbolically associated with ‘dirt poor’.

Smudge mistakes mini-misogynist Charles for a wimpy one, who gradually warms to her. I believe this is how the reader is supposed to interpret Charlie’s character arc too, but I keep thinking about the distinction between sexism and misogyny, and how Browne only subverts one of those aspects for his boy character.

DESIRE

The mother wants to retain her position as a privileged white woman. (Yes, animals can still be white women.) Her son is going the same way, but for now he wants to enjoy the freedom of being a kid without the heavy weight of responsibility. He wants a playmate.

The father searches the classifieds looking for a job, which will allow him to provide for his family. But because economic power is so connected to being a man, the fact that he has no hope of conforming to society’s expectation of ‘Man’, this exclusion has ostensibly afforded him a different kind of freedom. He can sit in a park during the daytime and spend time with his daughter.

The girl wants a playmate and the boy will have to do, seeing as there’s no one else.

OPPONENT

Everyone in this story is each other’s opponent, except for the dogs, whose easy friendliness juxtaposes against the reserve of the human characters — each at a different point on the ‘reserved’ spectrum.

Notice how the man and the woman exist at opposite ends of a shared park bench, with an ambiguous pole used as a framing device to split the pair apart. (For more examples of this see Composition In Film and Picturebooks.)

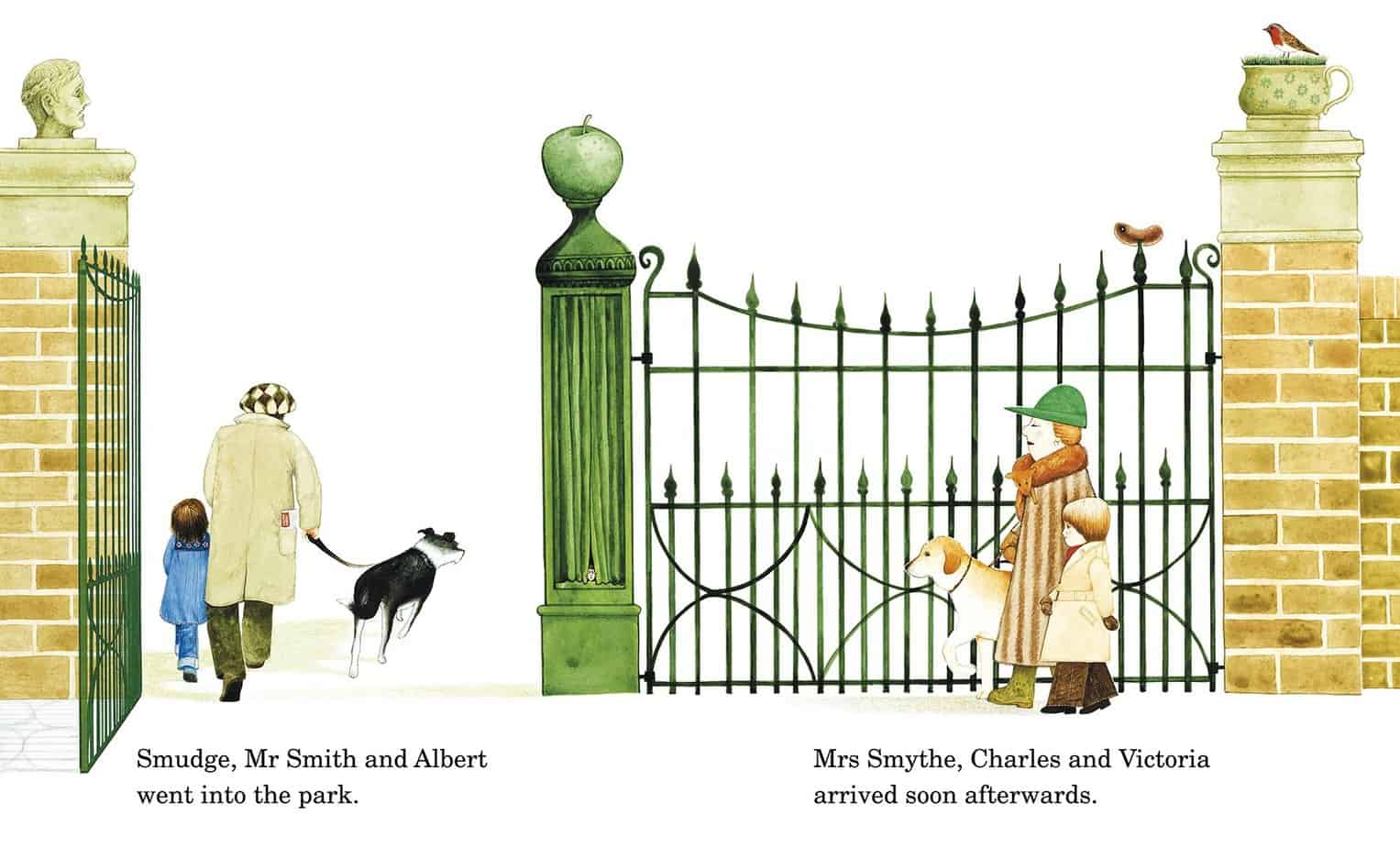

Another example of framing below. A pillar separates the families from one another. The poor family walk into white space (expressing their care-freedom) while the rich, upper-class family walk symbolically in front of prison-like bars.

PLAN

Mrs Smythe intends to go to the park to give her dog and son some fresh air and exercise. Mr Smith seems to be at the park because it is a pleasant place to sit and read the classifieds, quite possibly nicer than his own kitchen.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Each character has their own battle: For Mrs Smythe, the battle is in getting her dog and son under control. The dog might as well be her son. “Sit”, she tells her son.

For Mr Smith the battle is keeping his spirits up in the very dispriting state of being unemployed and needing a job.

For Charles, the battle is against his oppressive mother and her expectations that he become a ‘real man’.

For the carefree Smudge, an example of the Female Maturity Formula, her job is to keep her father, and then the boy, happy.

ANAGNORISIS

Although the parallactic plot structure combined with surrealist illustrations are unusual in picture books, the message of this story is not unusual for the category: Don’t suppress children’s natural inclination to have fun. Don’t pass on your own class prejudices because we really need to stop perpetuating the idea that some people are more worthy than others.

Another picture book with a different structure, different art style but identical message is Who Wants To Be A Poodle I Don’t by Lauren Child. I don’t buy the binary that some picture books are didactic while others are not. All stories contain a message, even if that message is conveyed by what they leave out rather than what goes in. More useful: to draw a distinction between implicit and explicit messaging.

Another implicit message in Voices In The Park seems to be this: “They were poor but they were happy.” I’m not so comfortable with this one. It’s a very old message, connected to Christianity (and probably to other world religions). In this story, the father and daughter are poor, but they are clearly more carefree than the mother and her son, who are rich. Because of cognitive biases, the reader will connect a cause and effect to these universal archetypes, and I believe this is intended.

It is somewhat true that money can’t buy happiness. It is also true that a base amount of household income is vital for a base level of happiness. The misconception ‘that poor people are happier’ can be misappropriated by the wealthy and powerful to assuage any guilt they might otherwise feel around resource hoarding. “Don’t worry about them. They’re poor, sure, but poor people are happy.”

NEW SITUATION

Smudge kept the flower.

This ending reminds me of a later (wordless) Canadian picture book called “Sidewalk Flowers” in which a generous girl also ends up with a flower at the end. The flower clearly symbolises innocent friendship in this story but I think it does a little more: A girl who ends up with a flower at the end of a story keeps some of her power/agency, in contrast to Giving Tree plots, in which femme characters are idealised as entirely self-sacrificing.

The flower functions as a reward for openness and kindness. Notice that the motif of the flower has been foreshadowed in the illustrations, encouraging readers to wonder what it means.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

It’s unlikely these kids go to the same school because of the British public/comprehensive divide in education, but this appears to be a fantasy park. So I hope they do meet each other again. Whether they do or do not, Charles will meet another kid in a park sometime. We simply don’t know if he’ll be more inclined to play with them or more inclined to talk to them, since his mother curtailed their visit this time due to inappropriate fraternising.

RESONANCE

Voices In The Park is loved by teachers because it requires students to read pictures as well as text, and offers a lot to talk about. There’s a sparse loneliness to Anthony Browne’s work, like looking at a Hopper painting. Even when characters share the same arena, they aren’t necessarily understanding one another. I prefer Browne’s picture books as daytime rather than before-bed reads.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

In adult storytelling, AMC TV series Breaking Bad explores similar themes. Walter White wears a distinctive hat, symbolic of patriarchy, specifically the financial stresses men are under due to capitalism. Across all seasons, Breaking Bad delves into what it means to be a man. Gus Fring understands Walter’s weakness and persuades him to keep cooking meth for him by delivering a persuasive and memorable lecture:

And a man, a man provides. And he does it even when he’s not appreciated, or respected, or even loved. He simply bears up and he does it. Because he’s a man.

Más (2010), Gus Fring

Analysis of “Voices In The Park” by Kylie Johnson

Orana : journal of school and children’s librarianship. Australia : Library Association of Australia, School & Children’s Libraries Sections 1977 – 2005 includes information about this picture book.

There’s an interview with Anthony Browne at The Guardian, and at TeachingBooks.net

Australia’s first Postmodern picture book is thought to be The Watertower, written by Gary Crew and illustrated by Steven Woolman (1994). See also Caleb, by the same duo. Unfortunately these books are a little difficult to source now.

Voices In The Park was awarded the Kurt Maschler Award (1982-1999), which specifically rewarded British picture books demonstrating excellent integration between words and pictures. The prize covered picture books and an illustrated book for a wide variety of ages, and Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland appears to be a particularly satisfying text to illustrate because it was won twice, by two different illustrators.

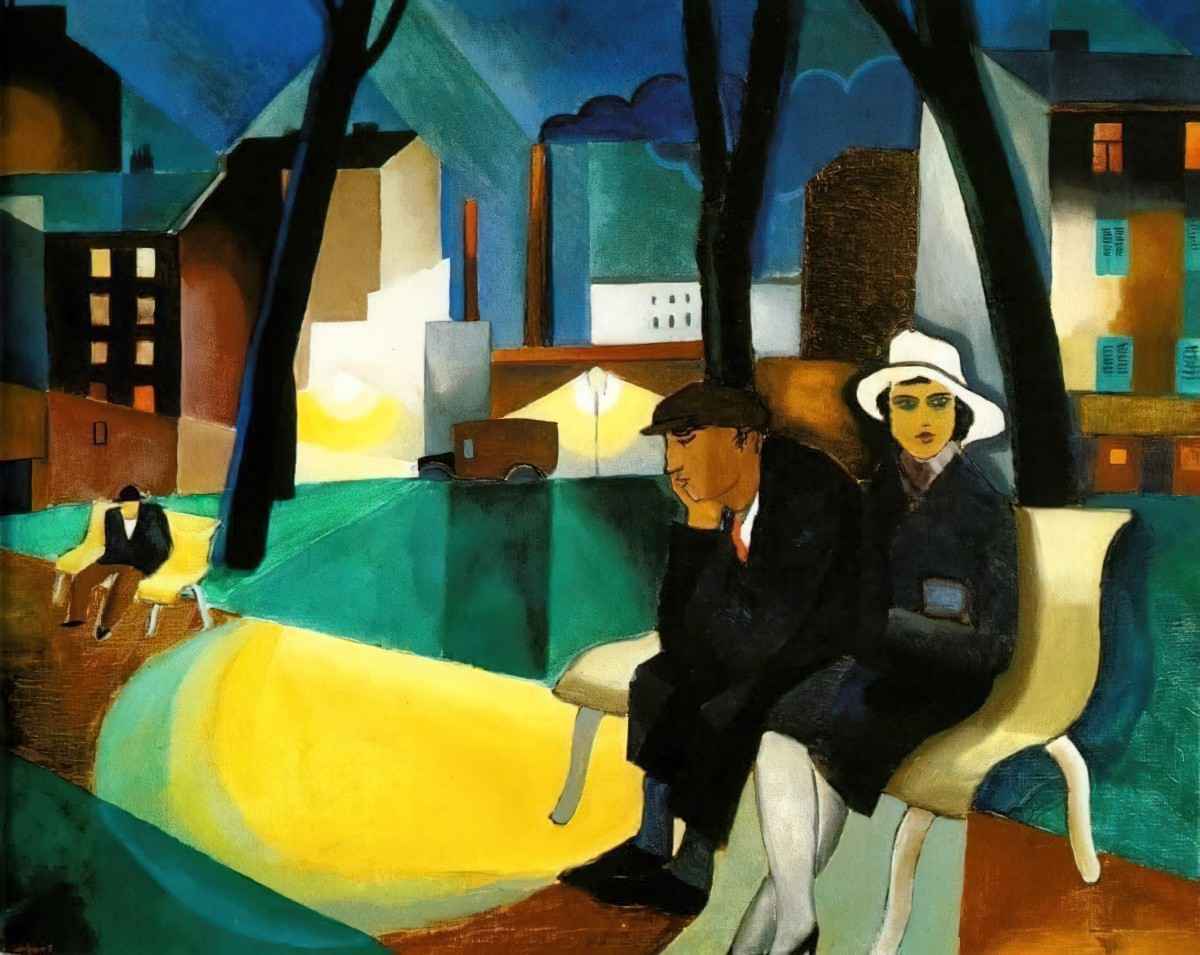

If you enjoyed the art in Anthony Browne’s Voices In The Park, I recommend you check out contemporary British artist Michael Kidd. The painting below could be straight out of this picture book.

“Mad Hatter’s Garden” by contemporary artist Michael Kidd b. 1937