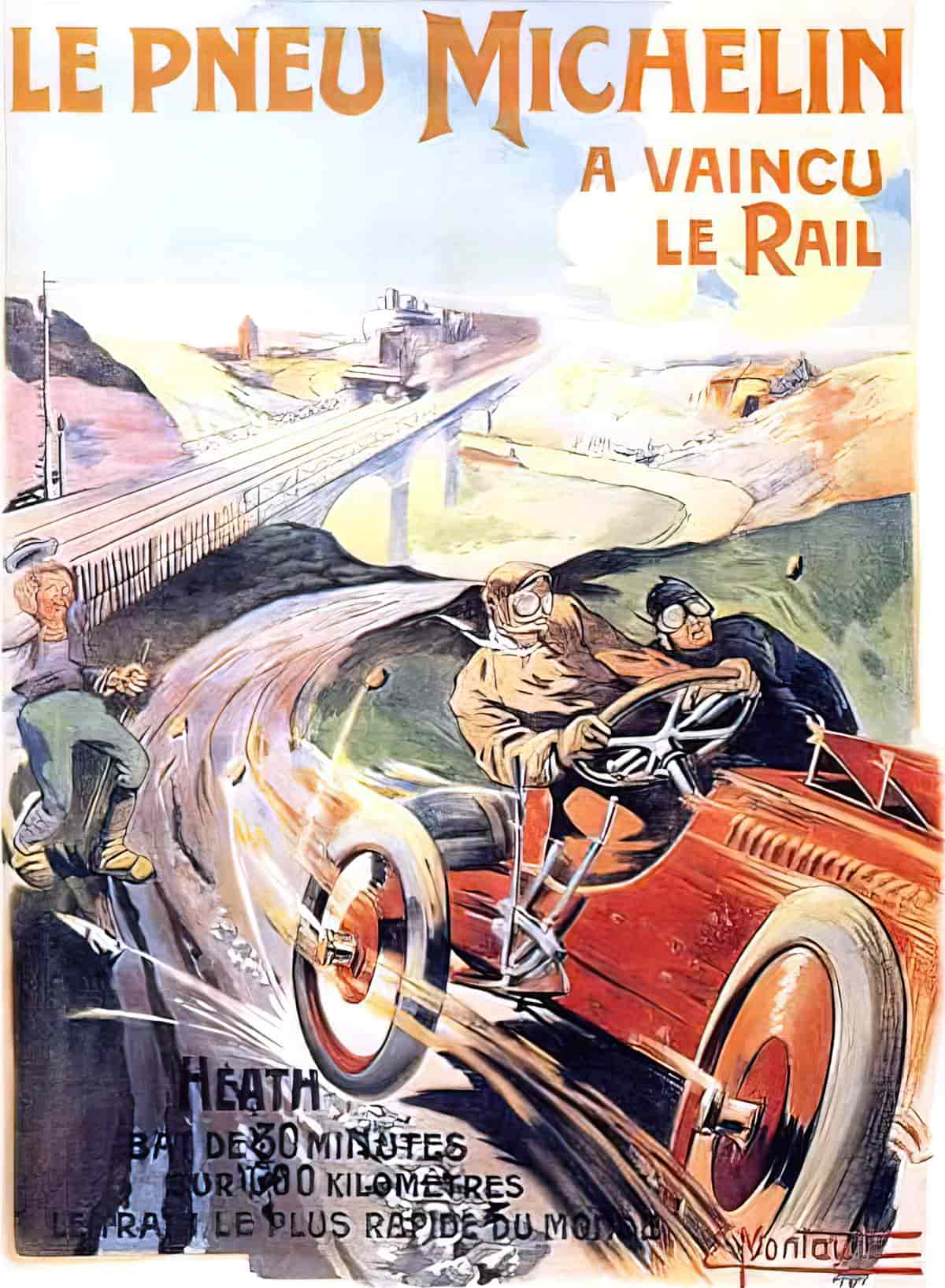

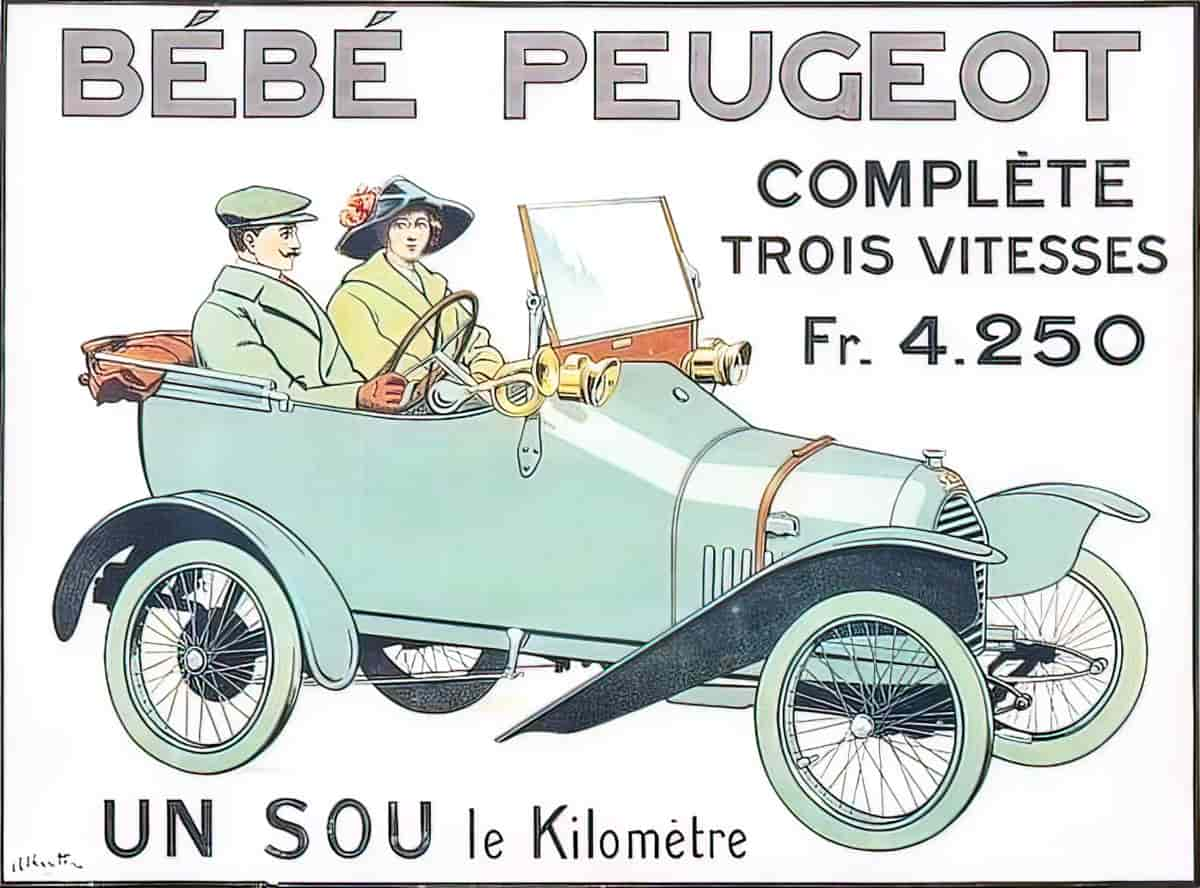

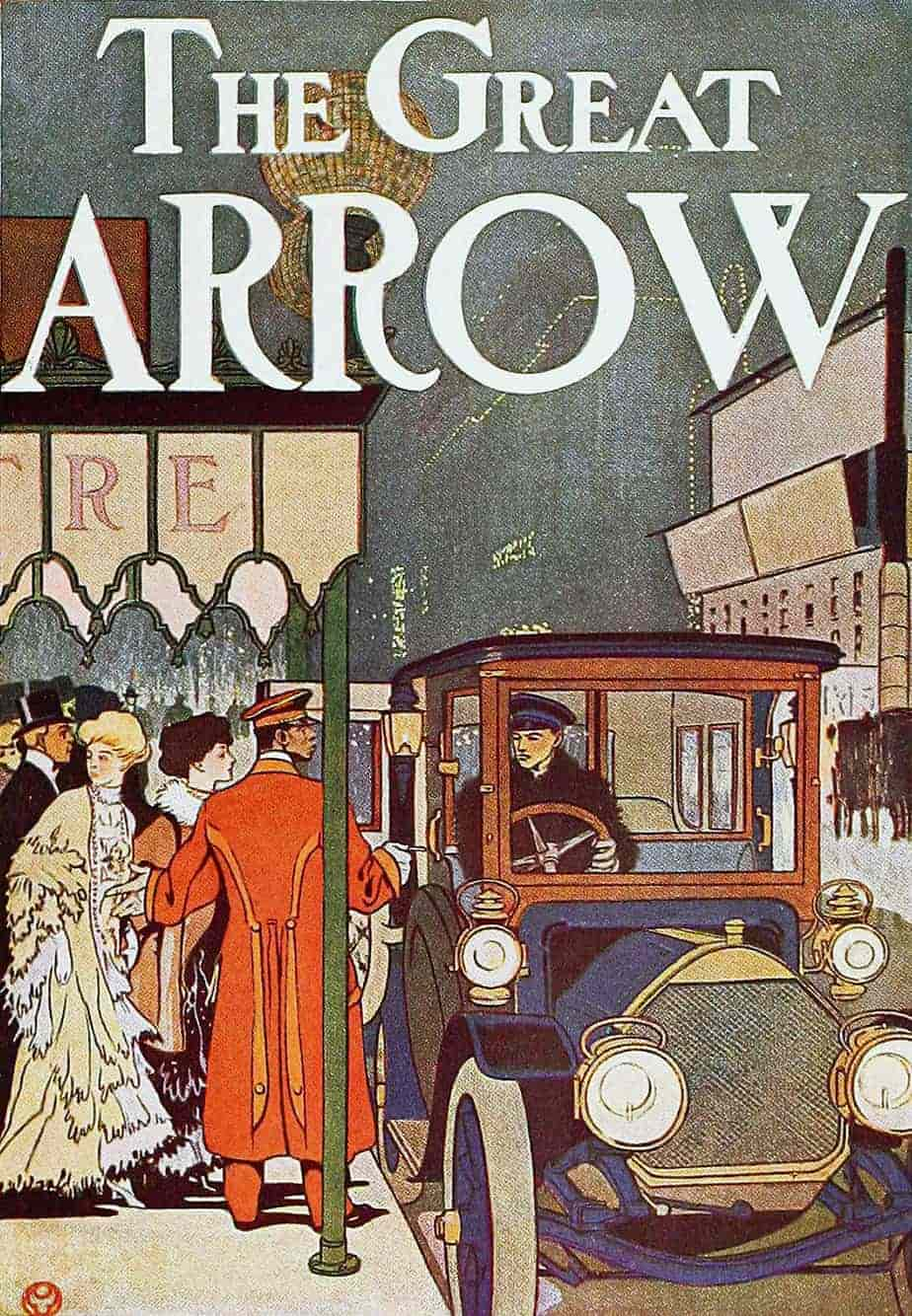

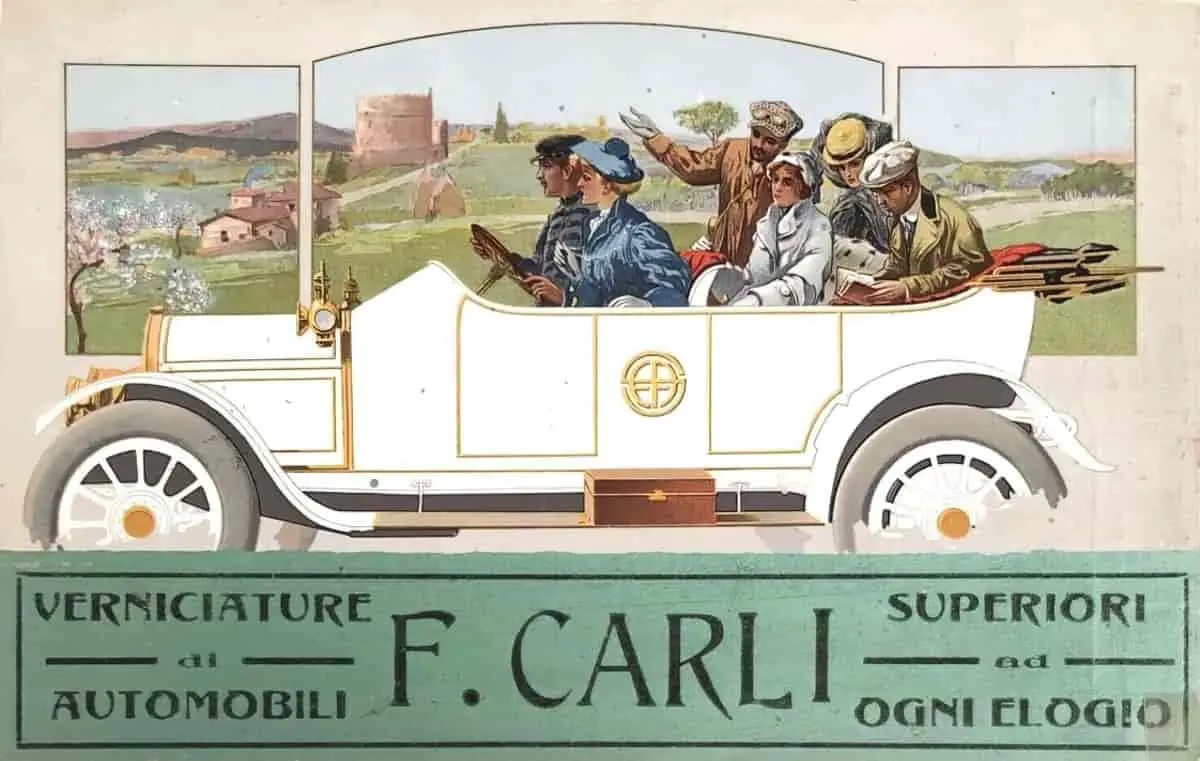

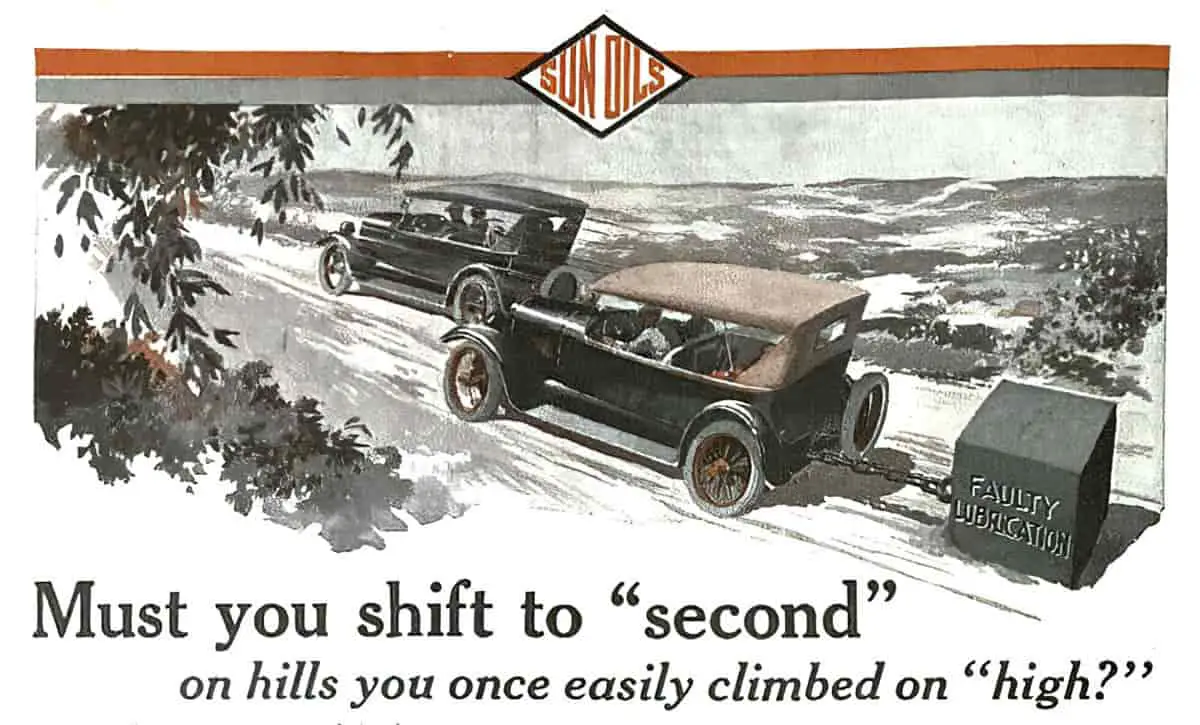

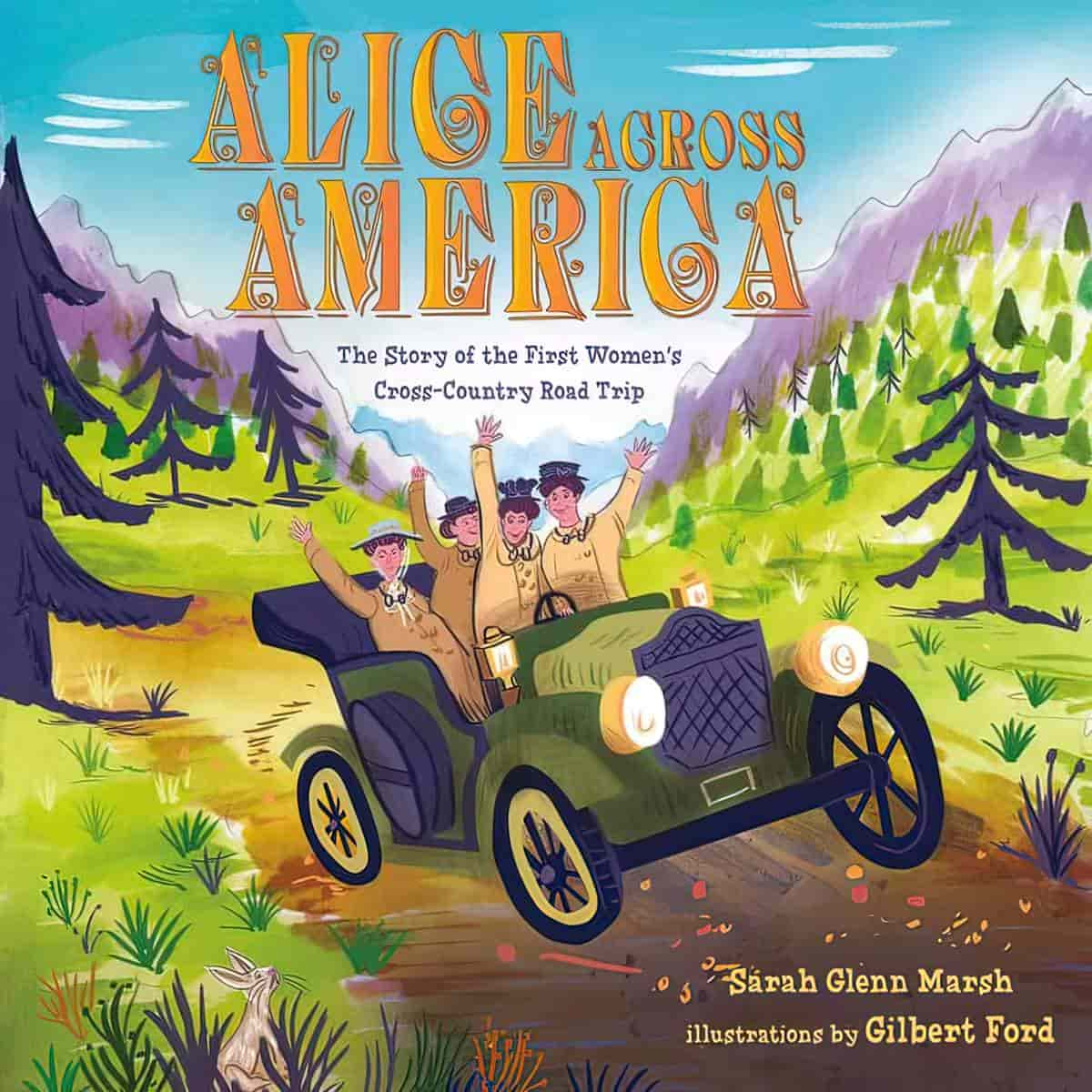

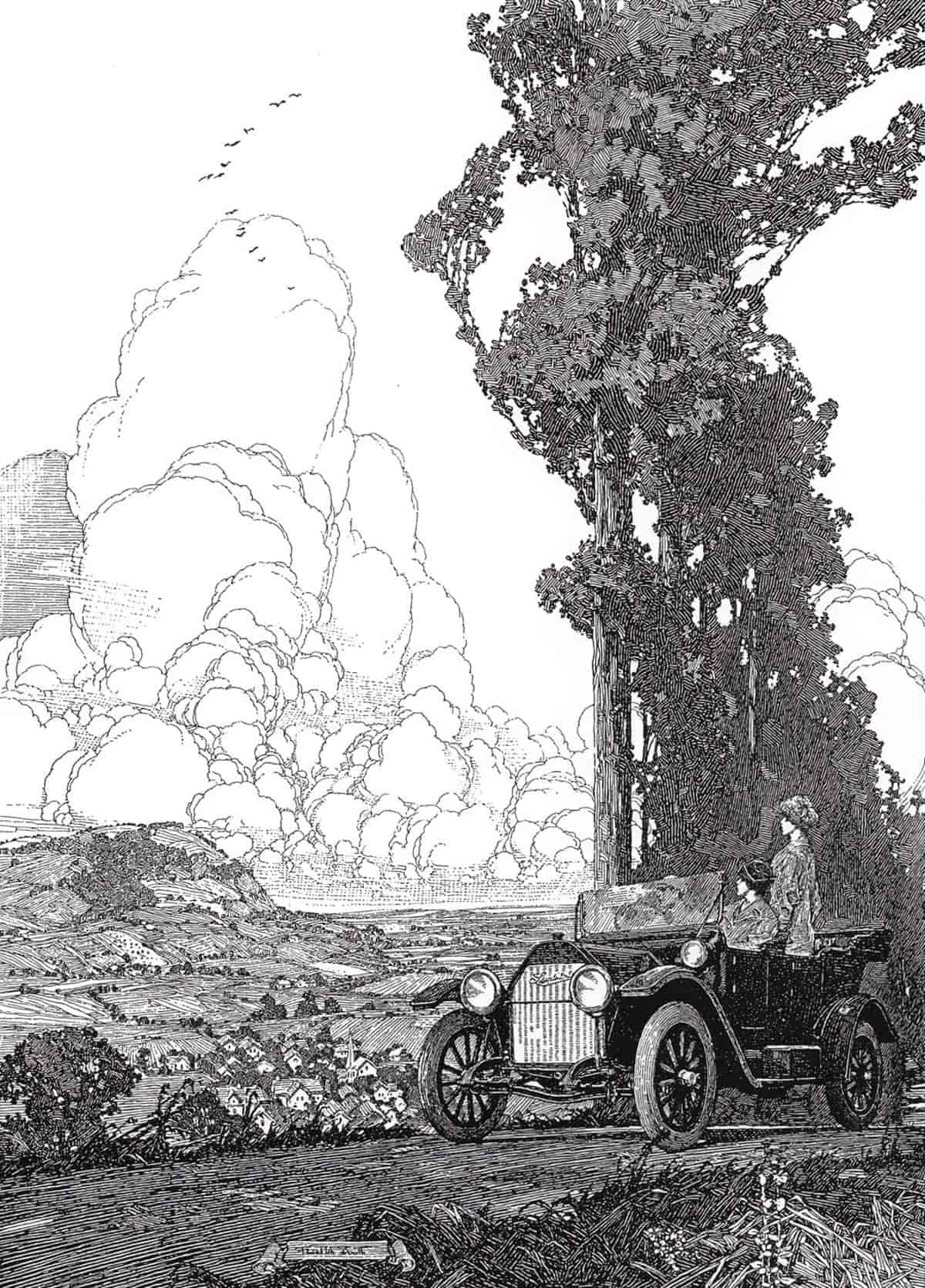

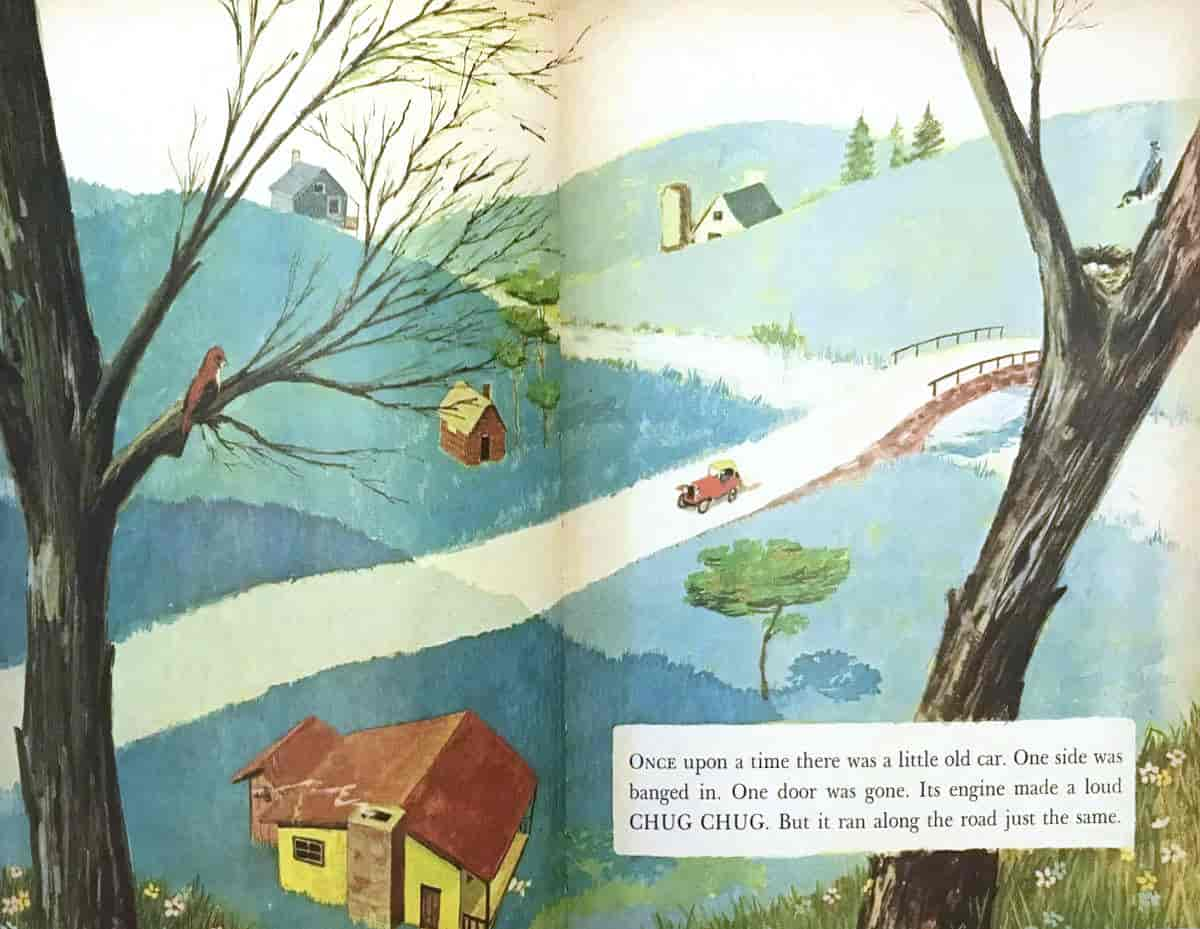

Early 1900s

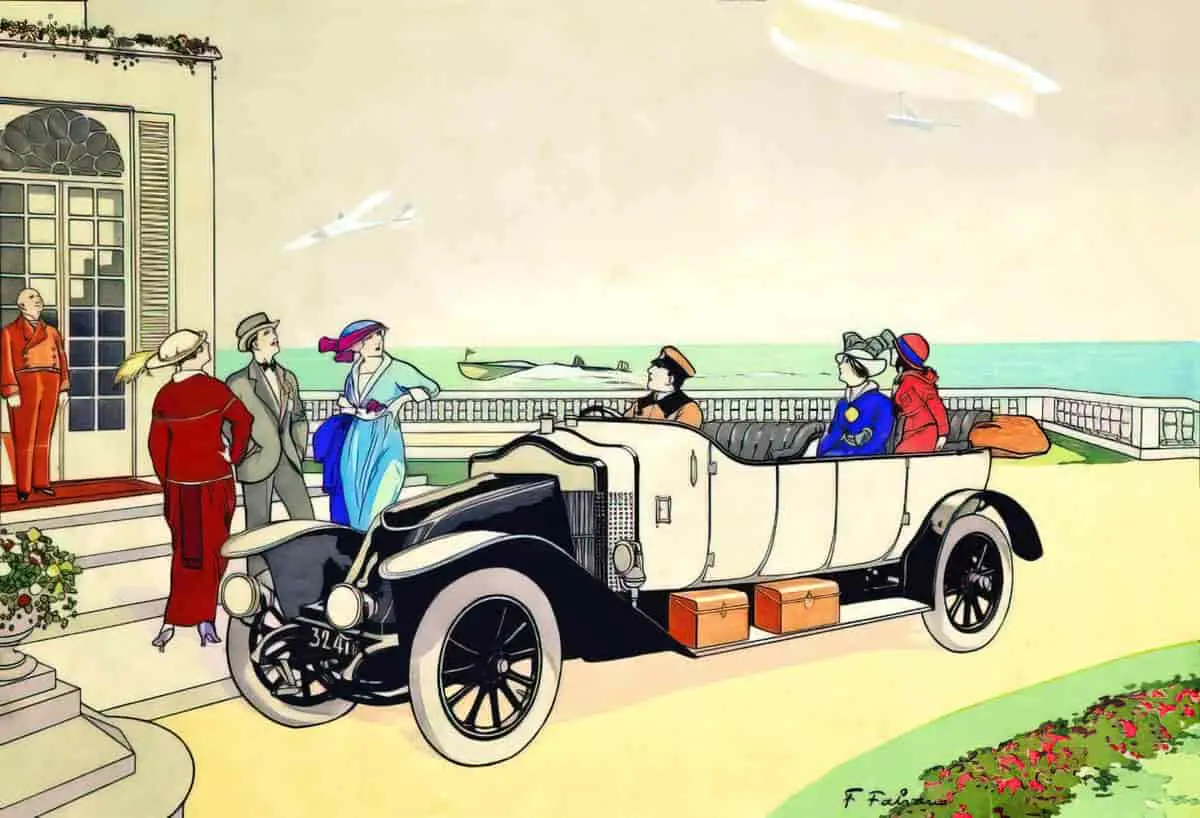

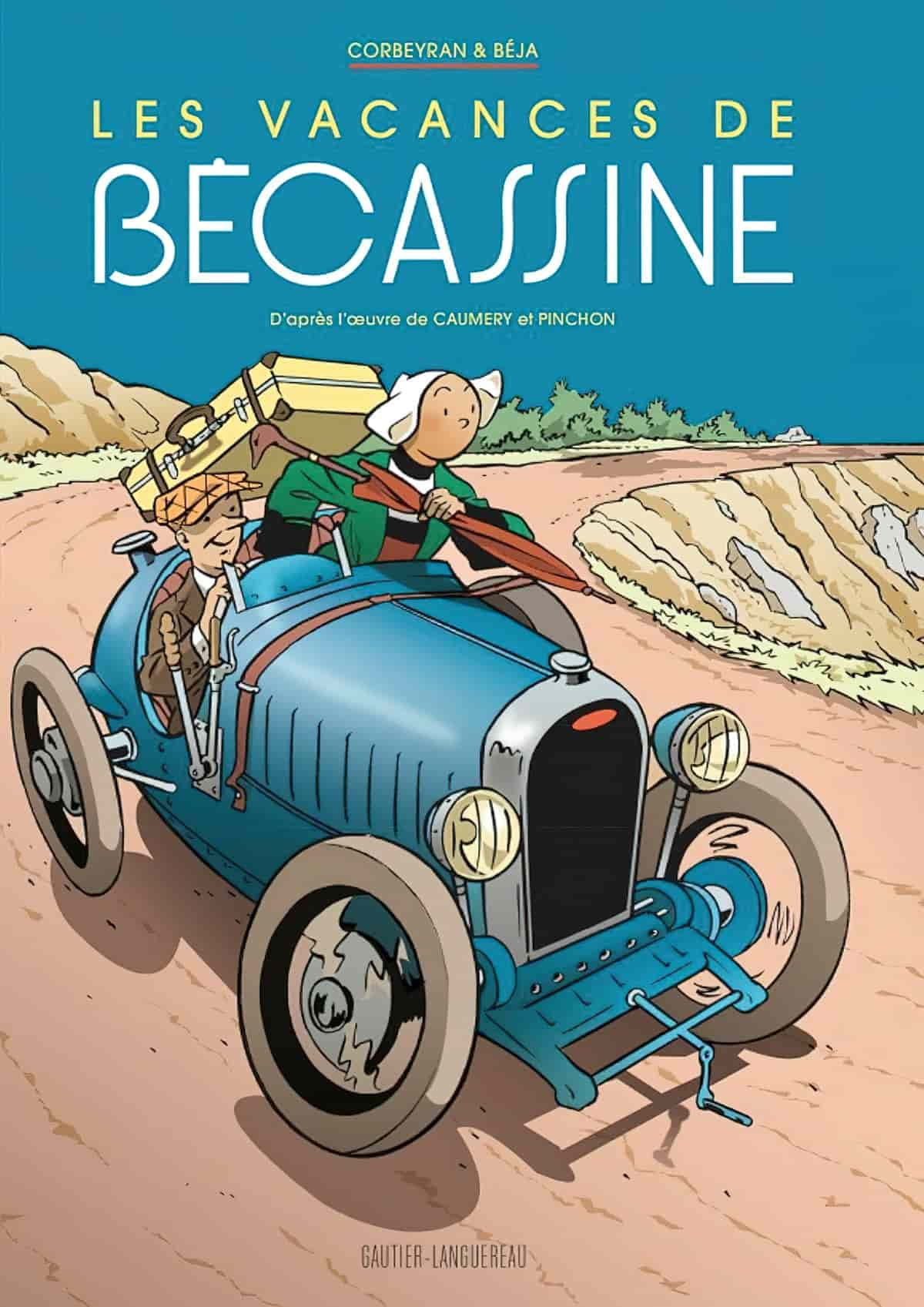

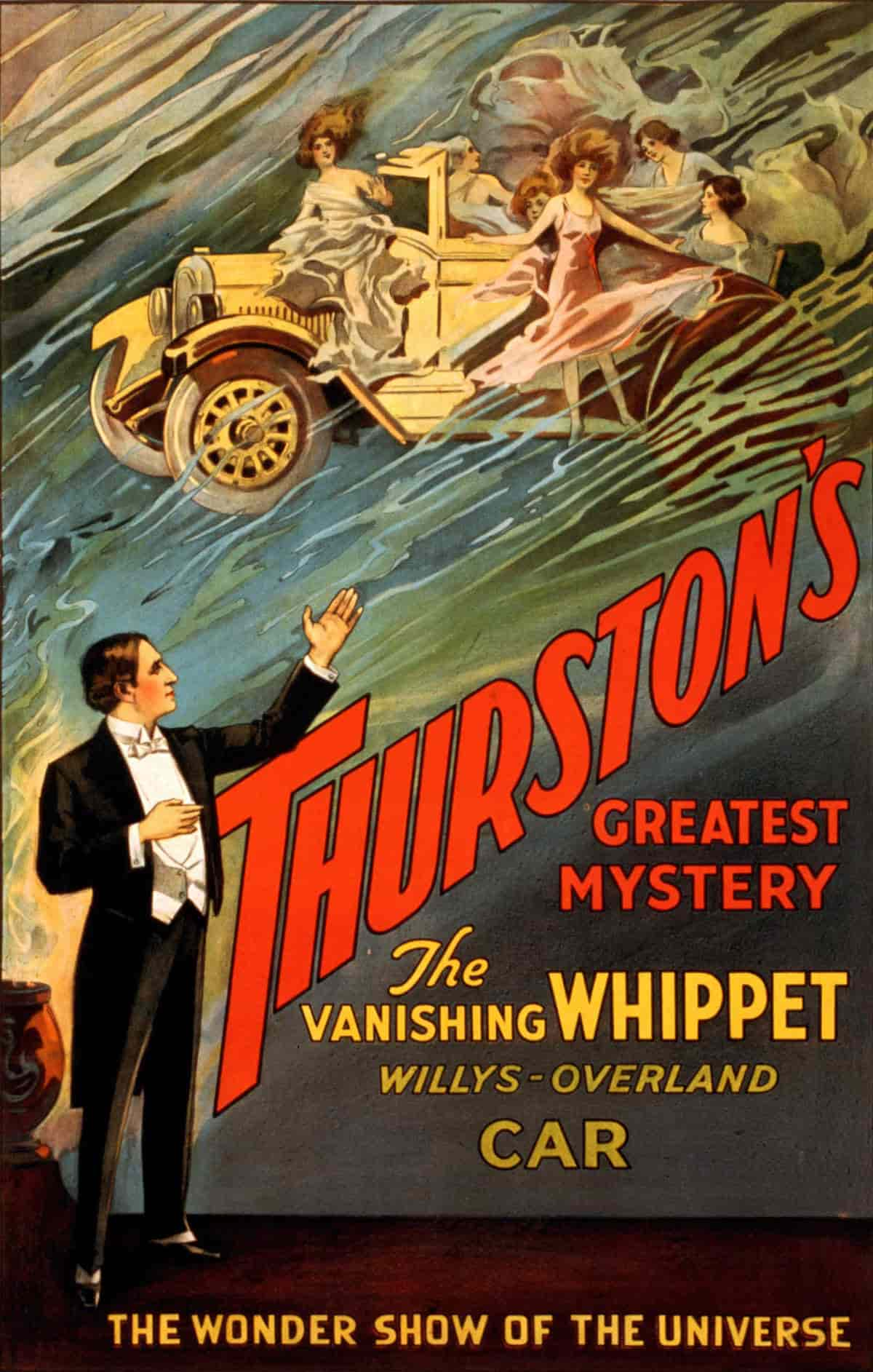

1910s

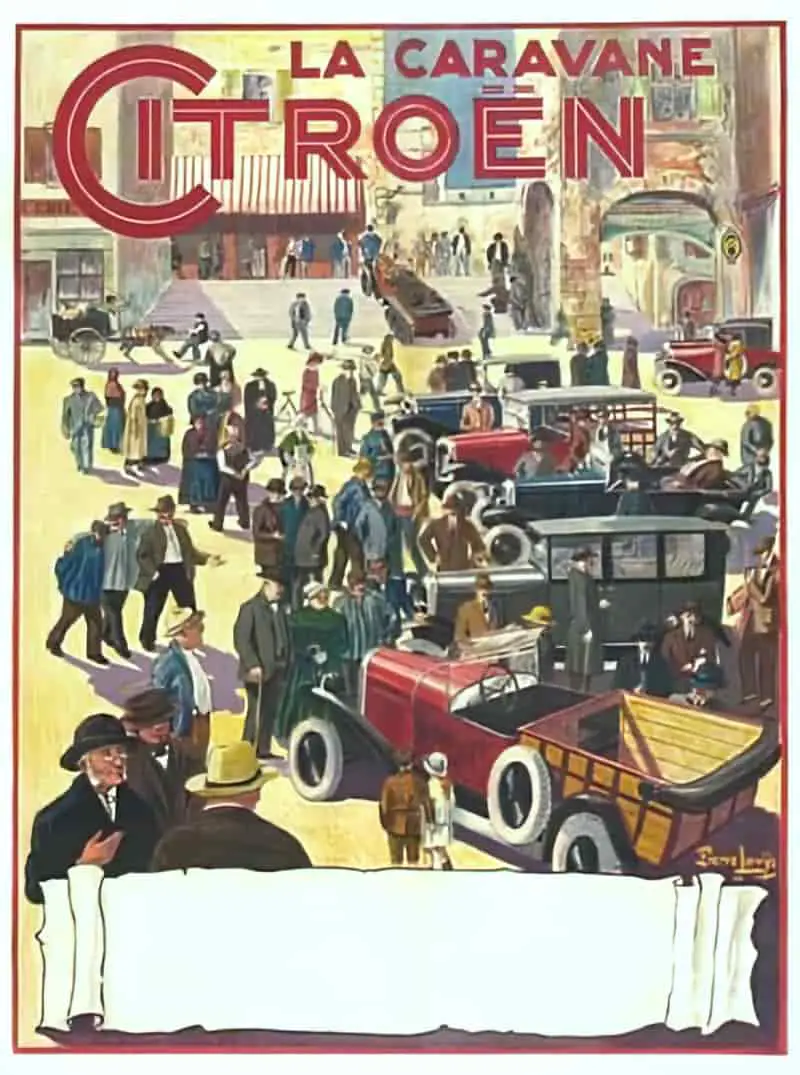

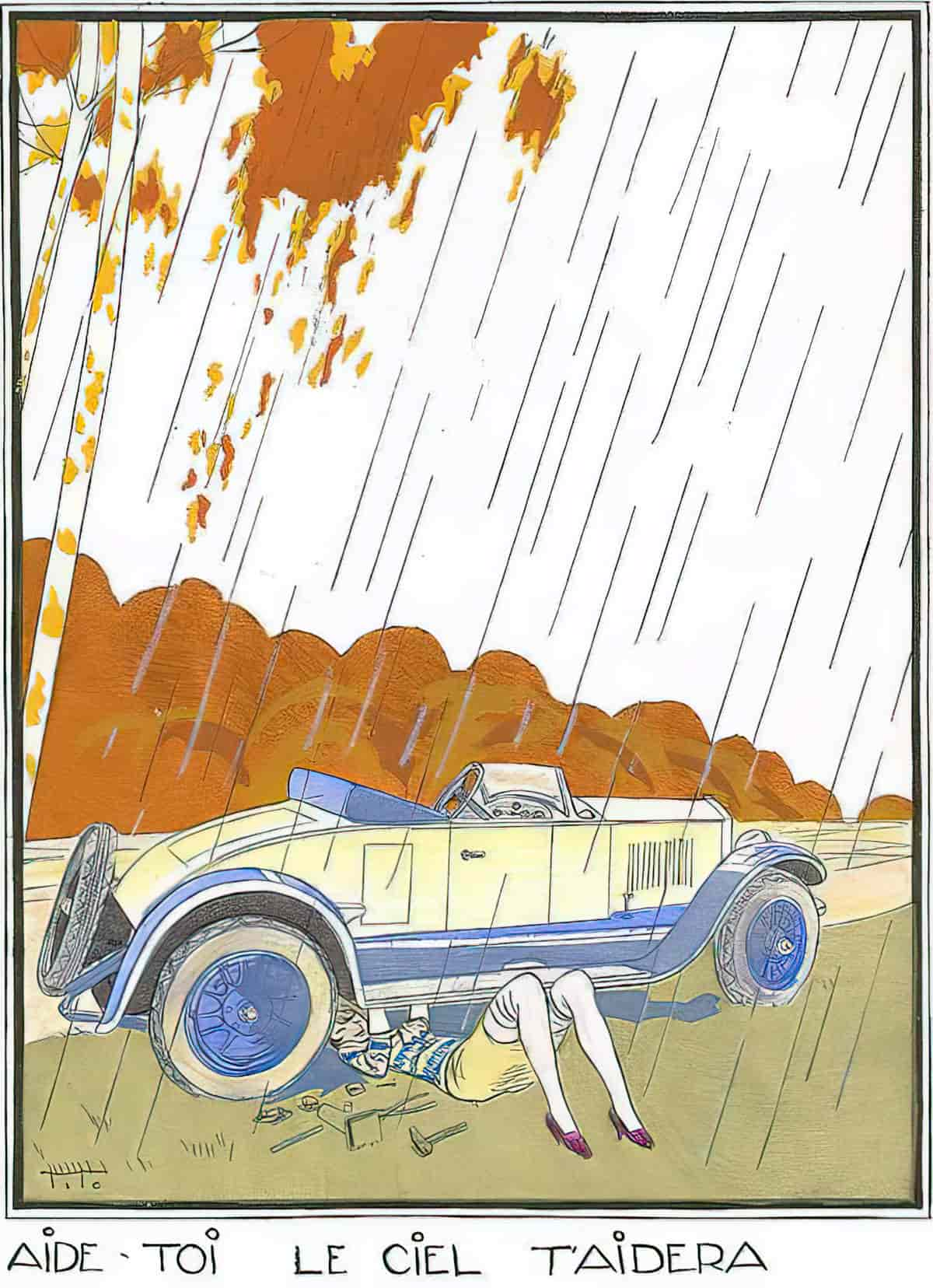

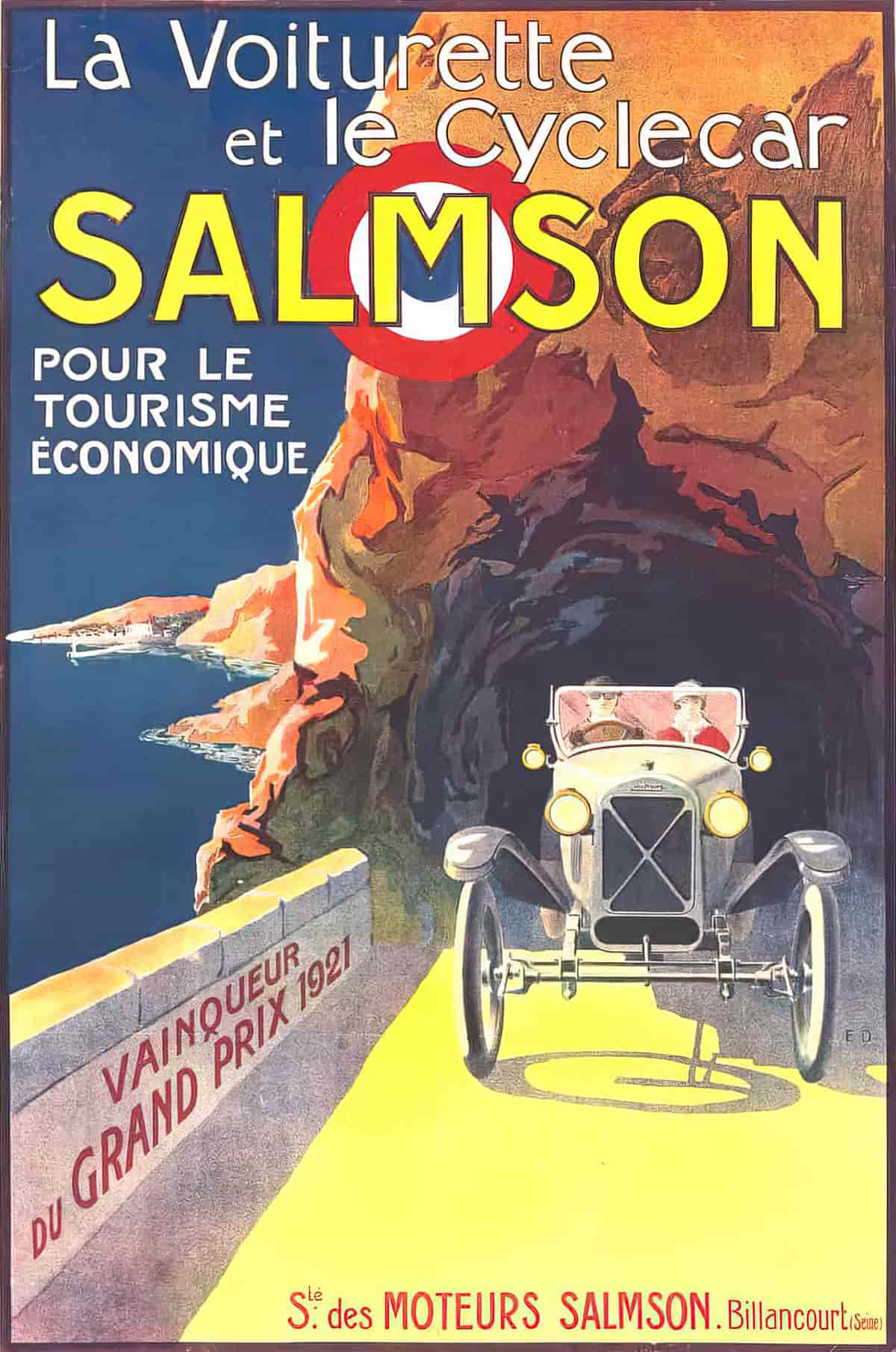

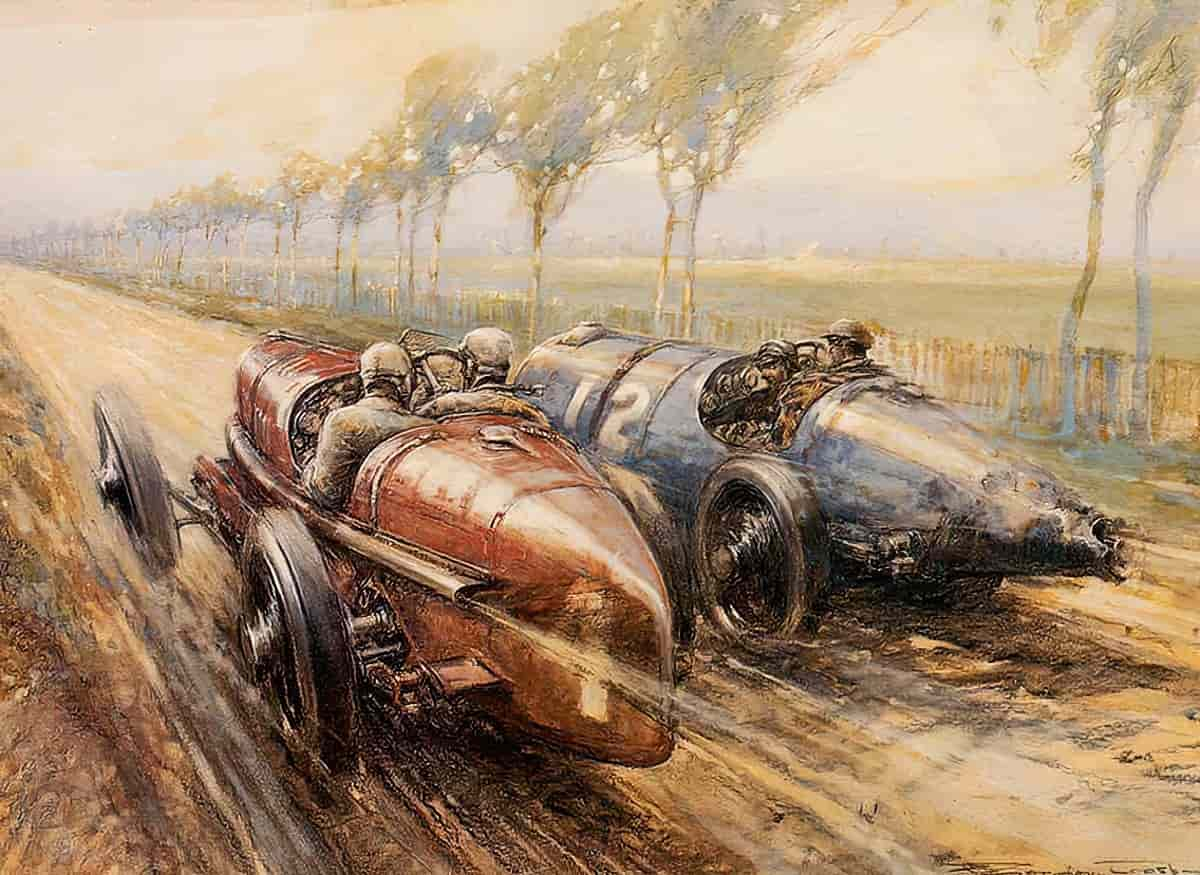

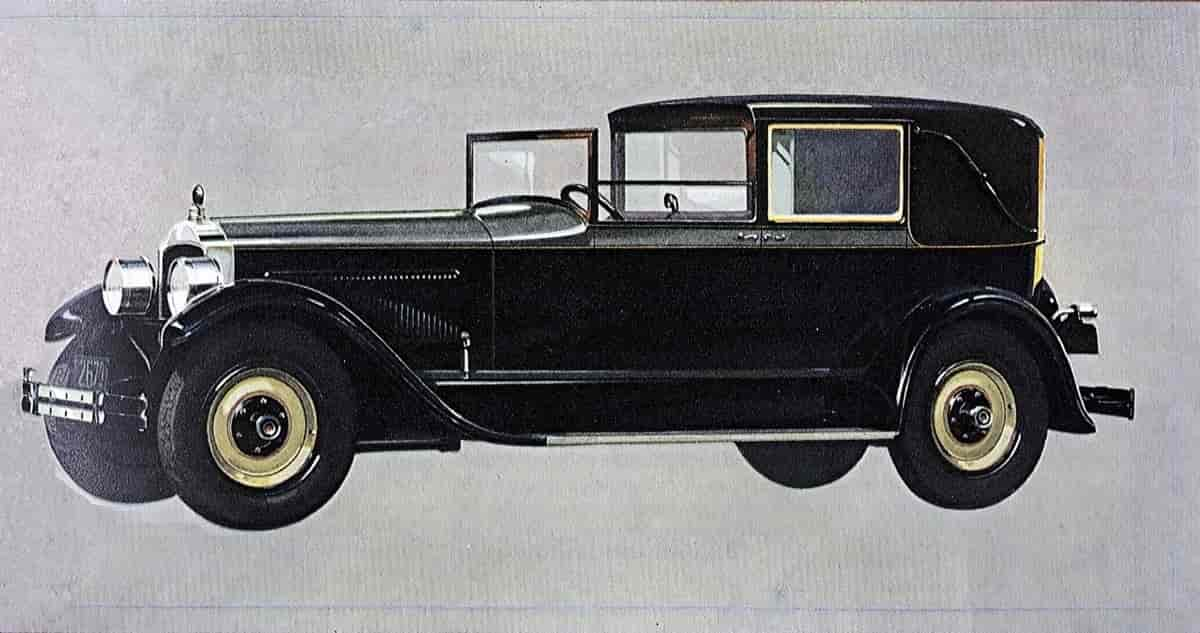

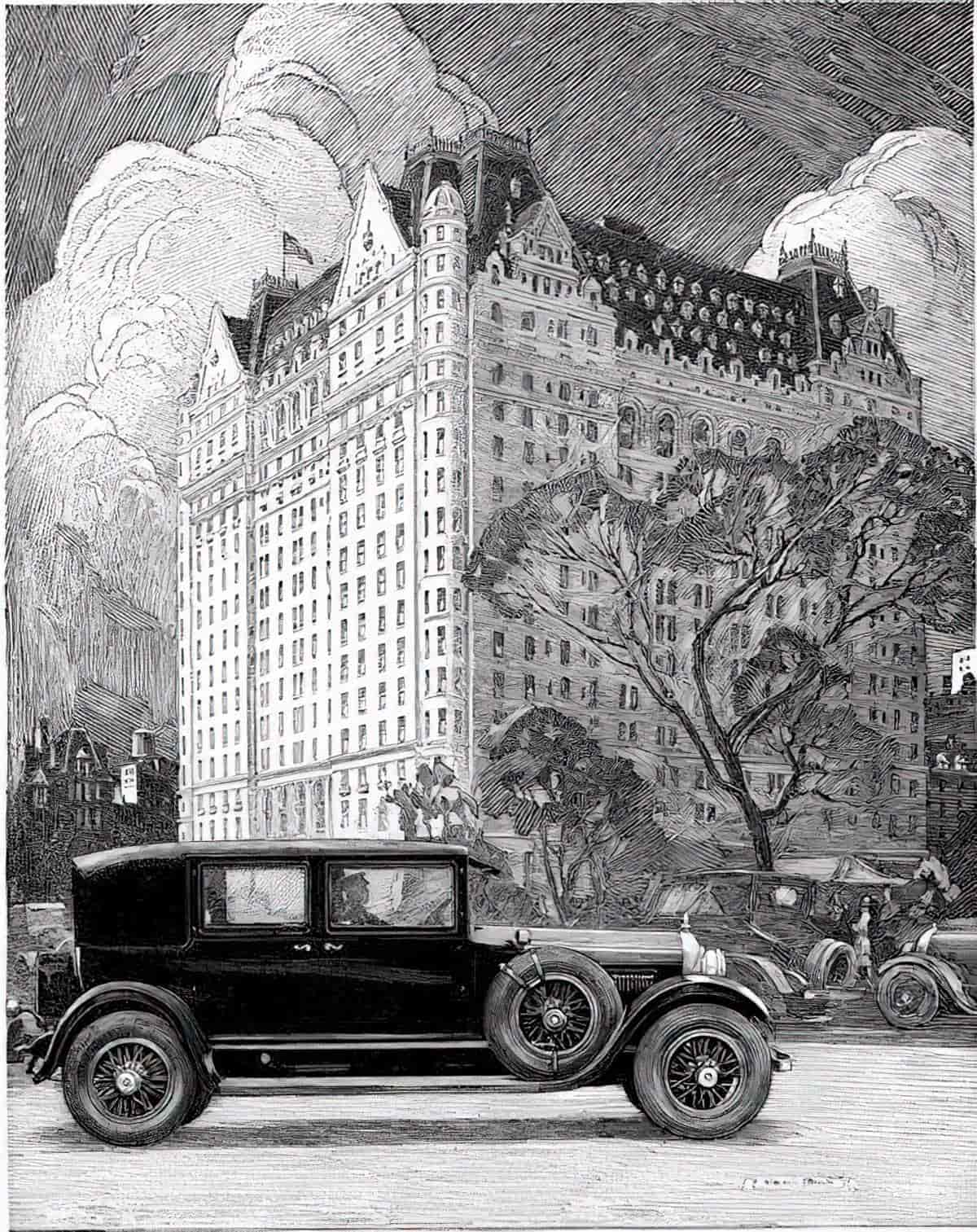

1920s

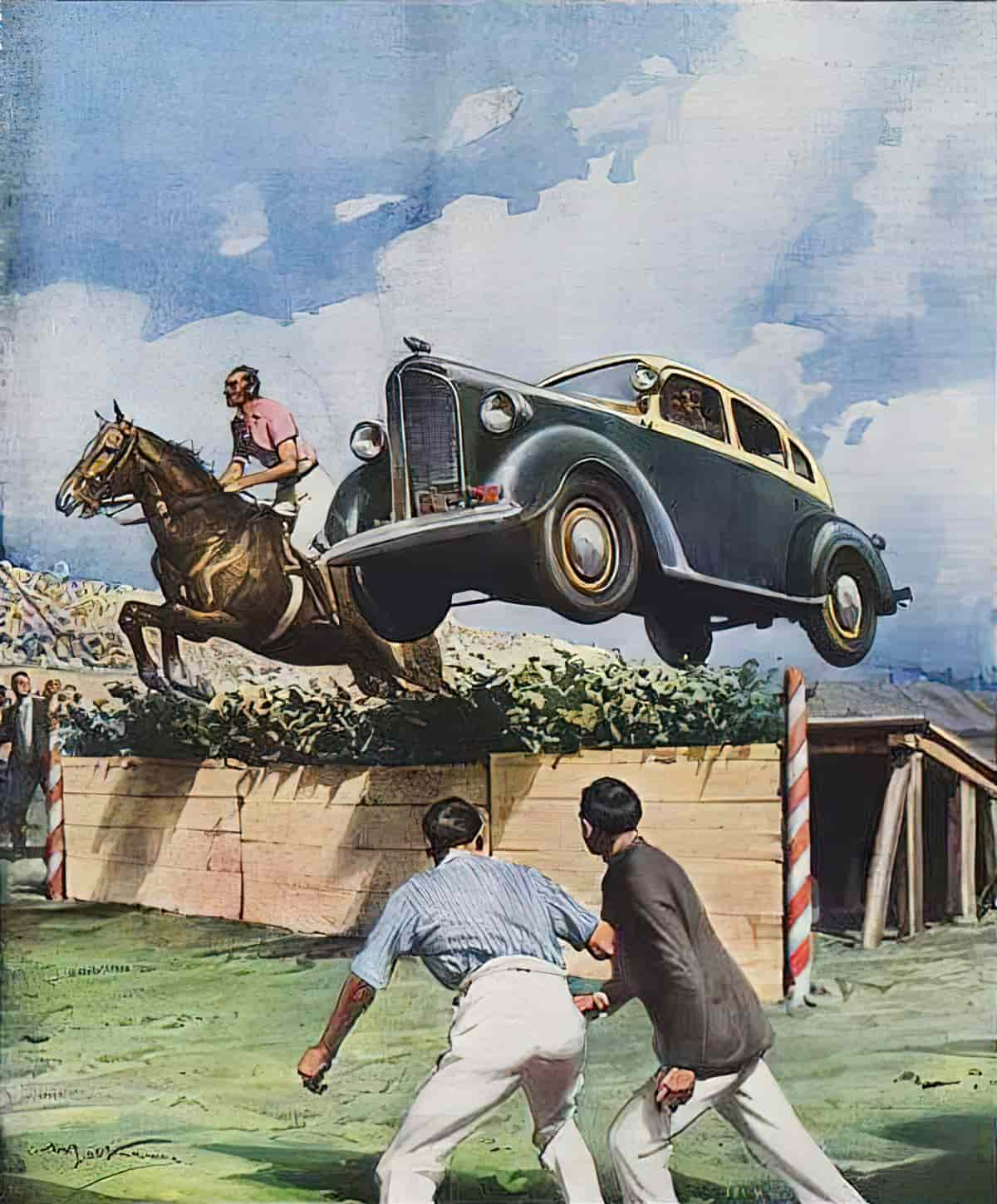

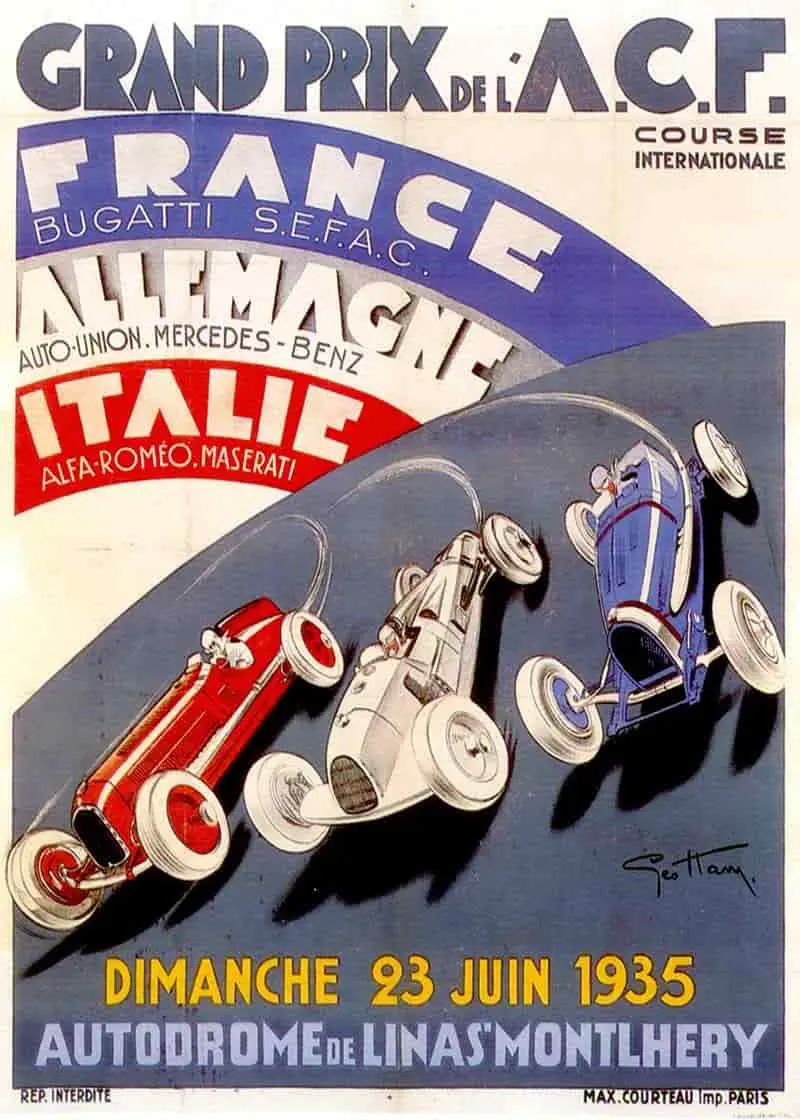

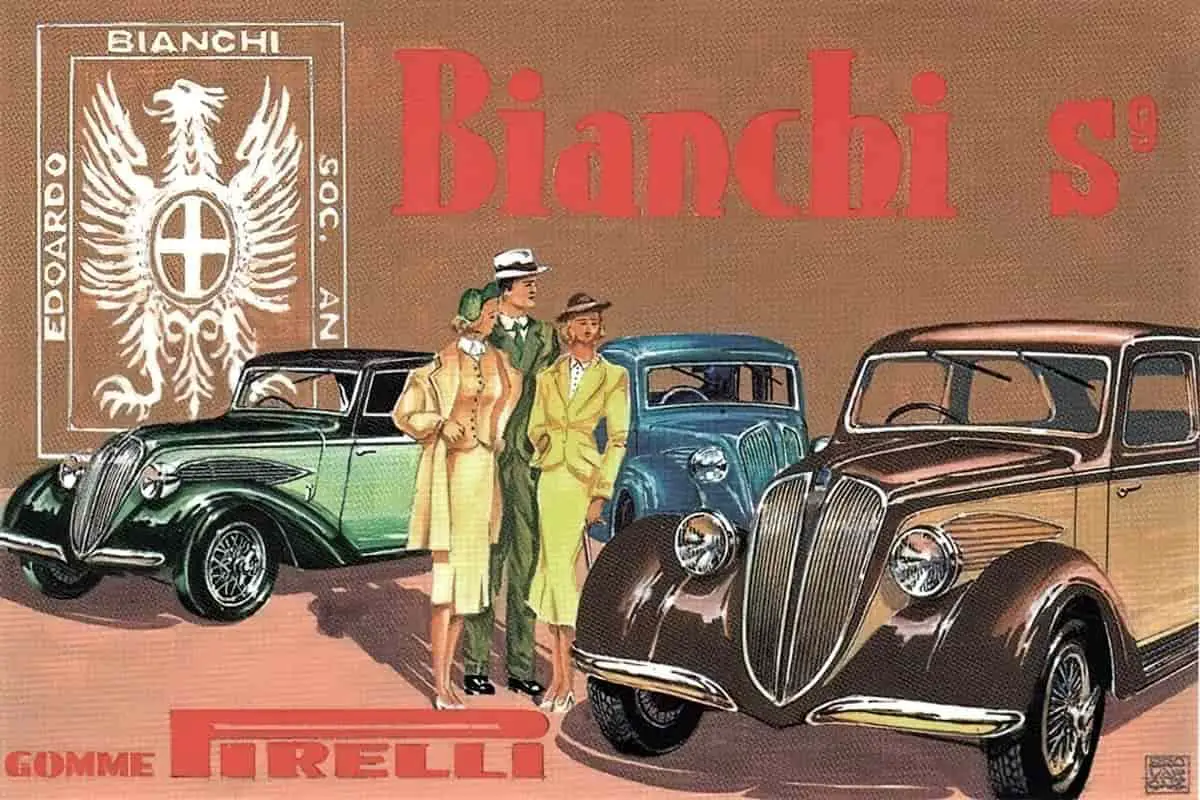

1930s

In the 1930s, motor vehicles still existed alongside horses.

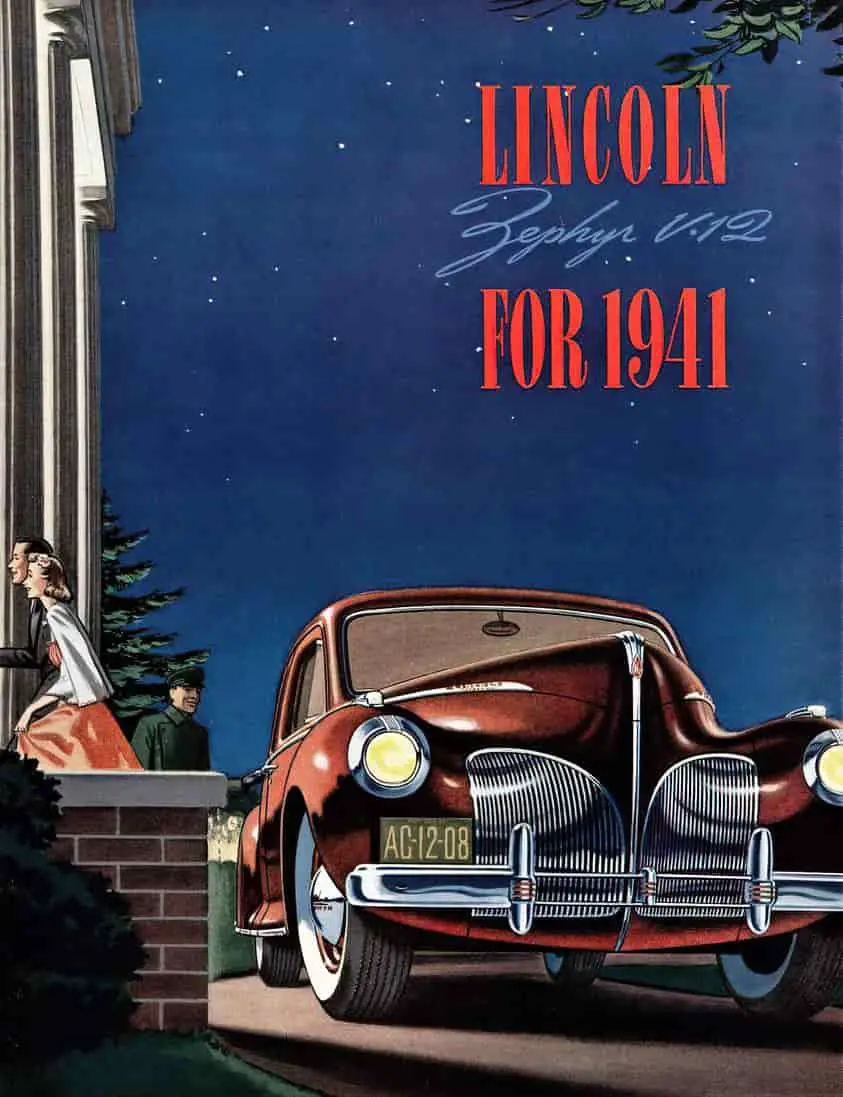

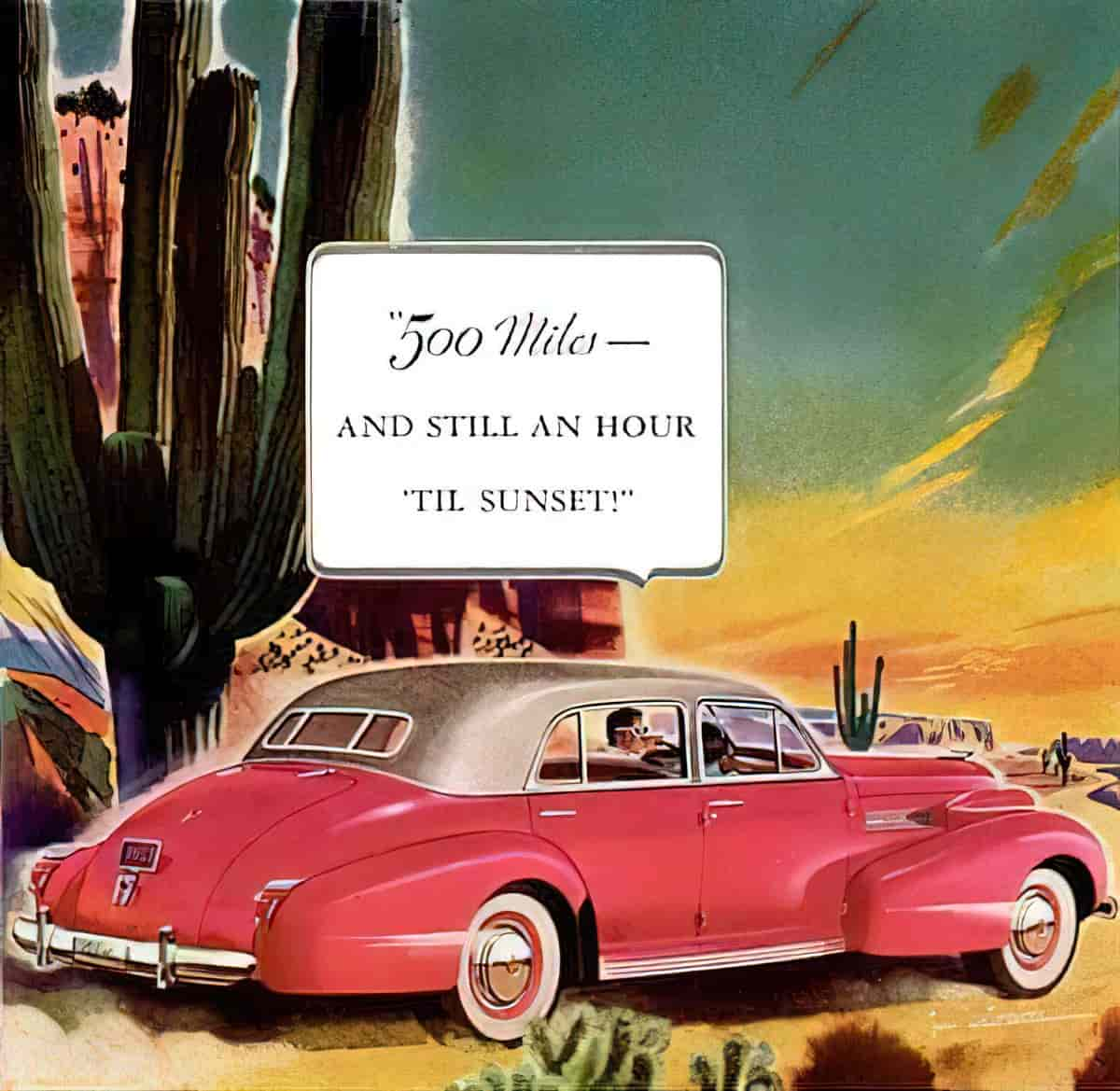

1940s

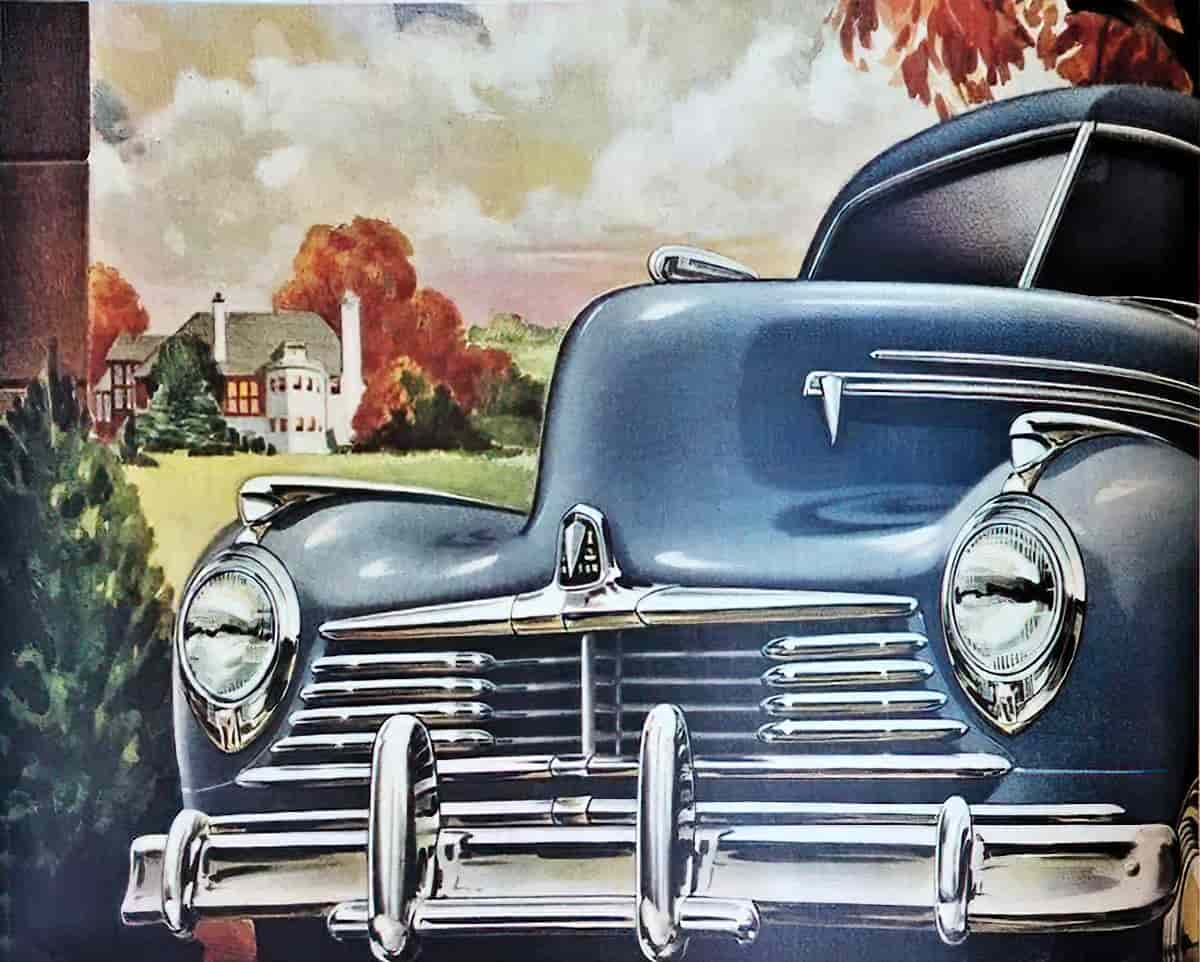

Film noir hit its heyday in the mid-to-late 1940s. The cars of ‘true’ noir tend to be large and have running boards, a platform attached to a vehicle’s doors that helps passengers easily board and leave the car.

Normal people: I left my sunglasses in the car.

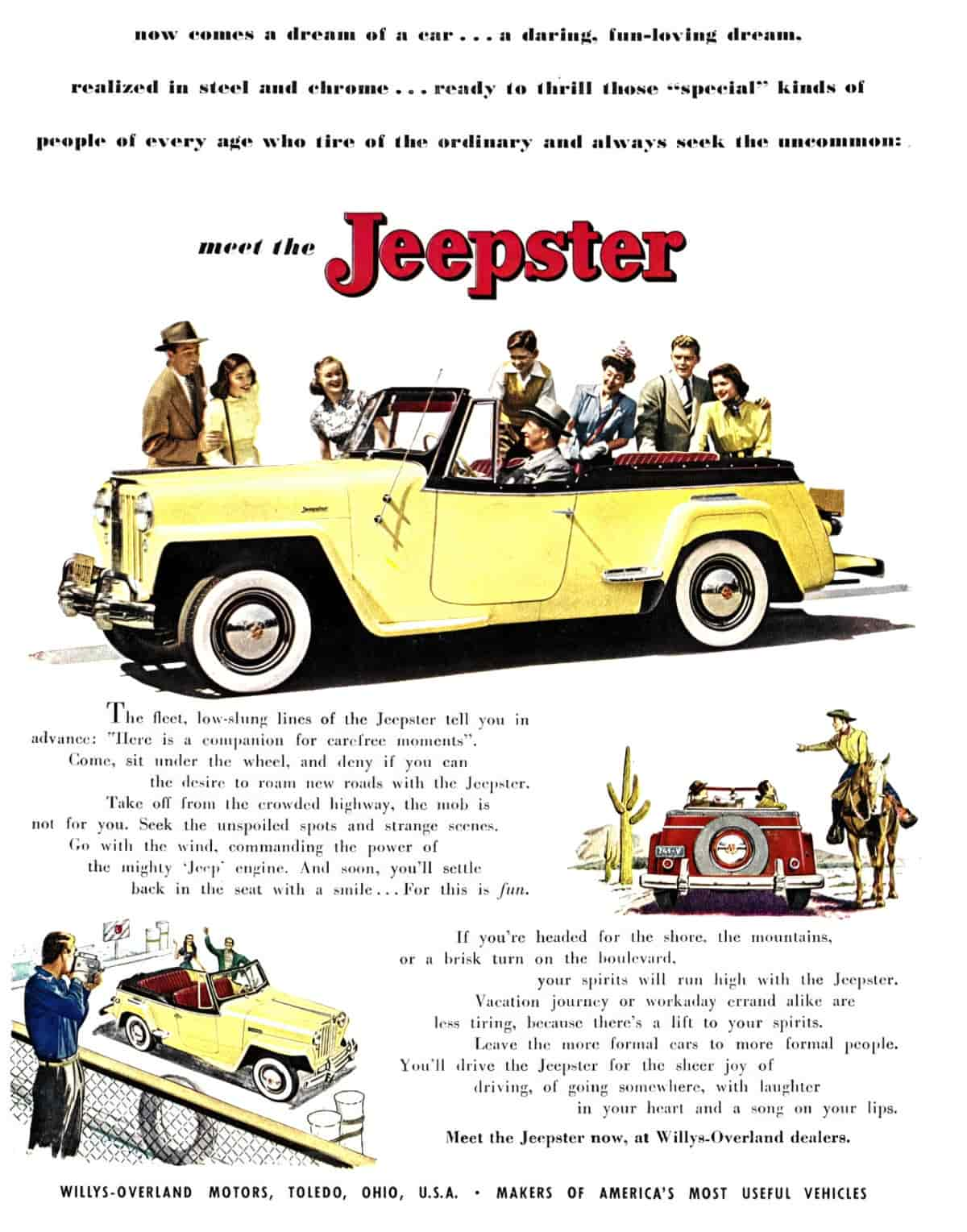

Jeep Owners: I Jeeped my Jeepgoggles in the Jeep™

@ronnui_

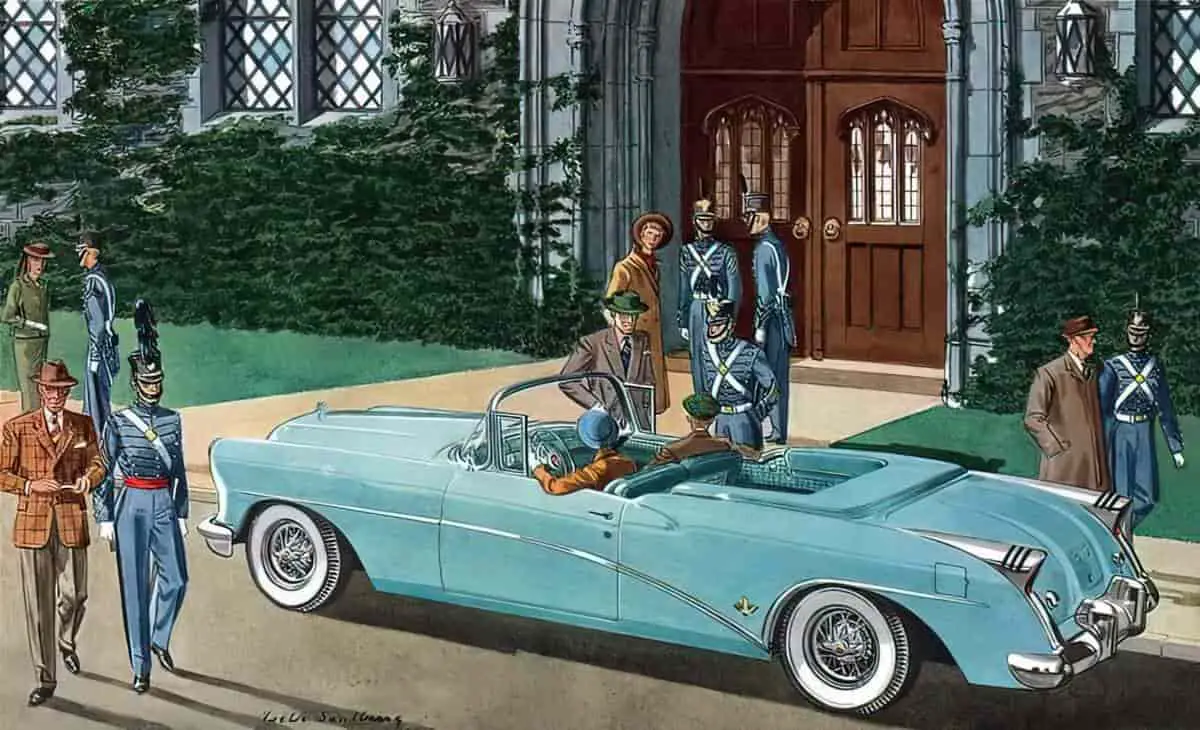

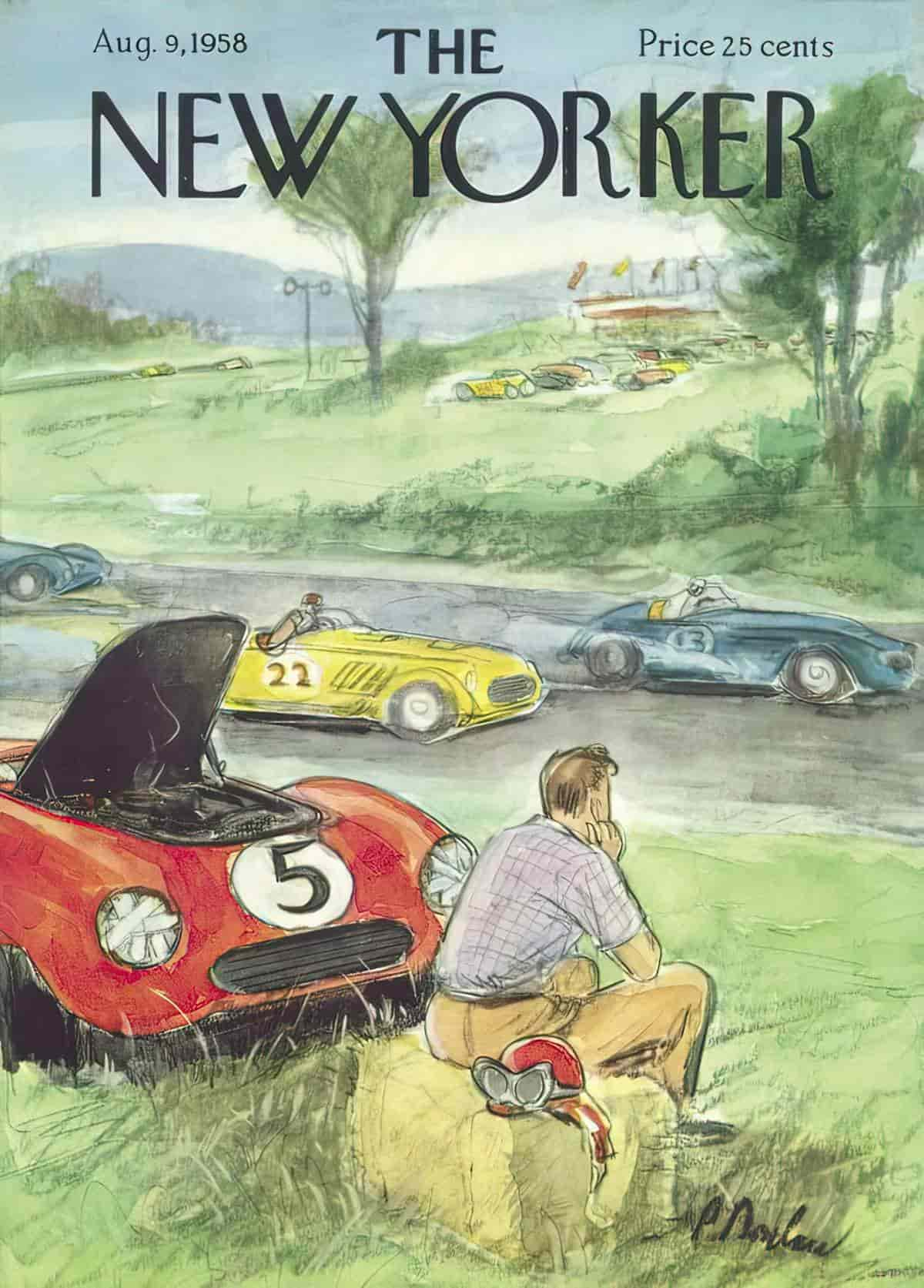

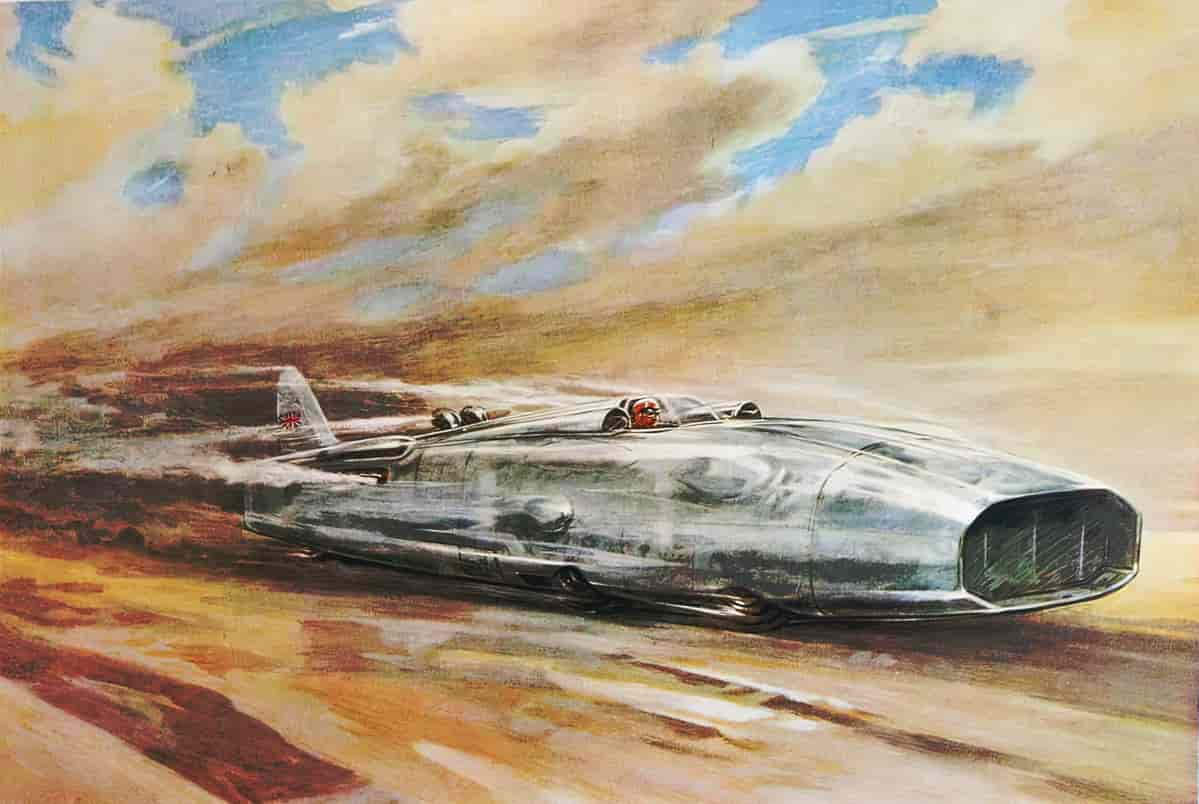

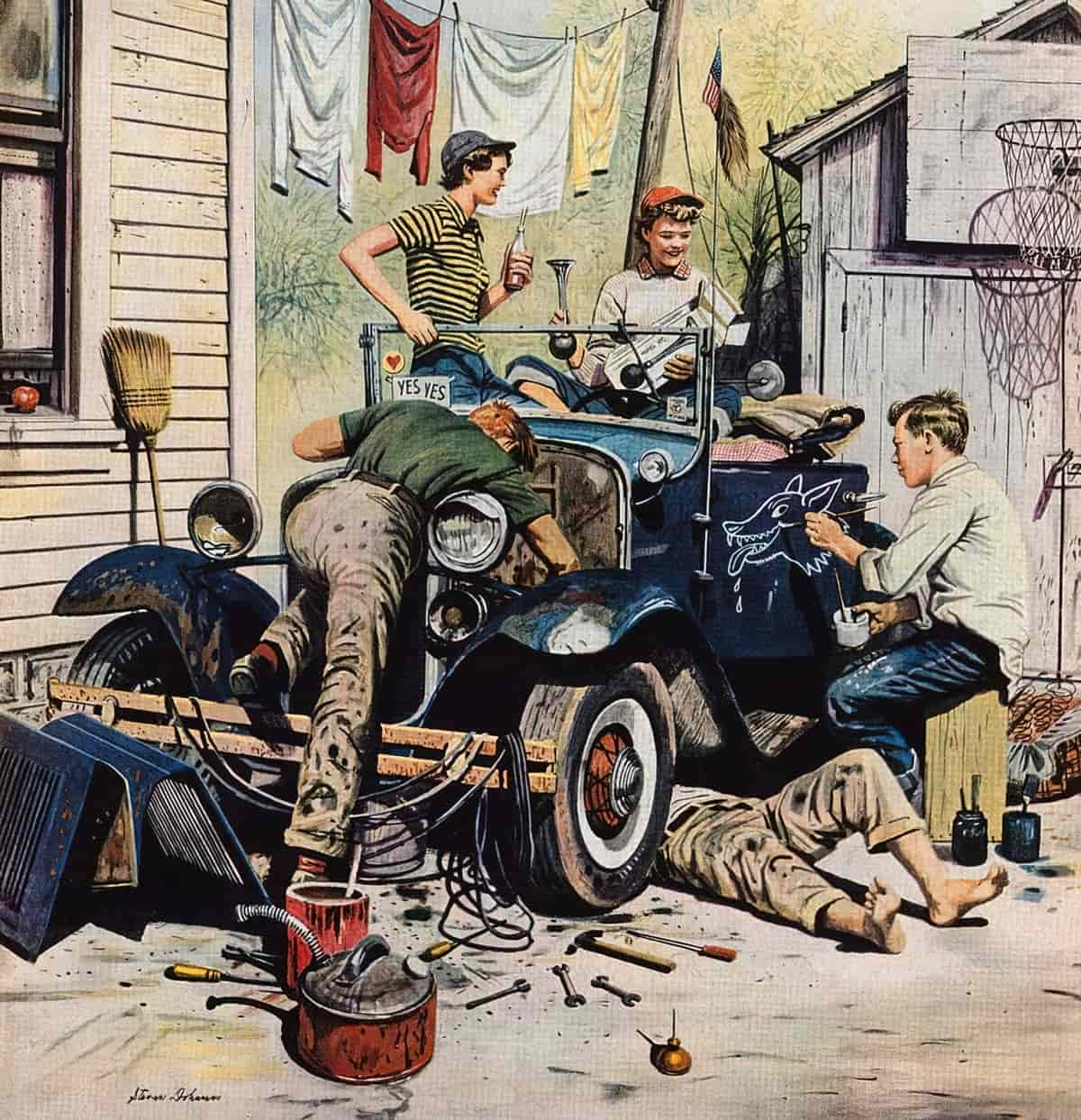

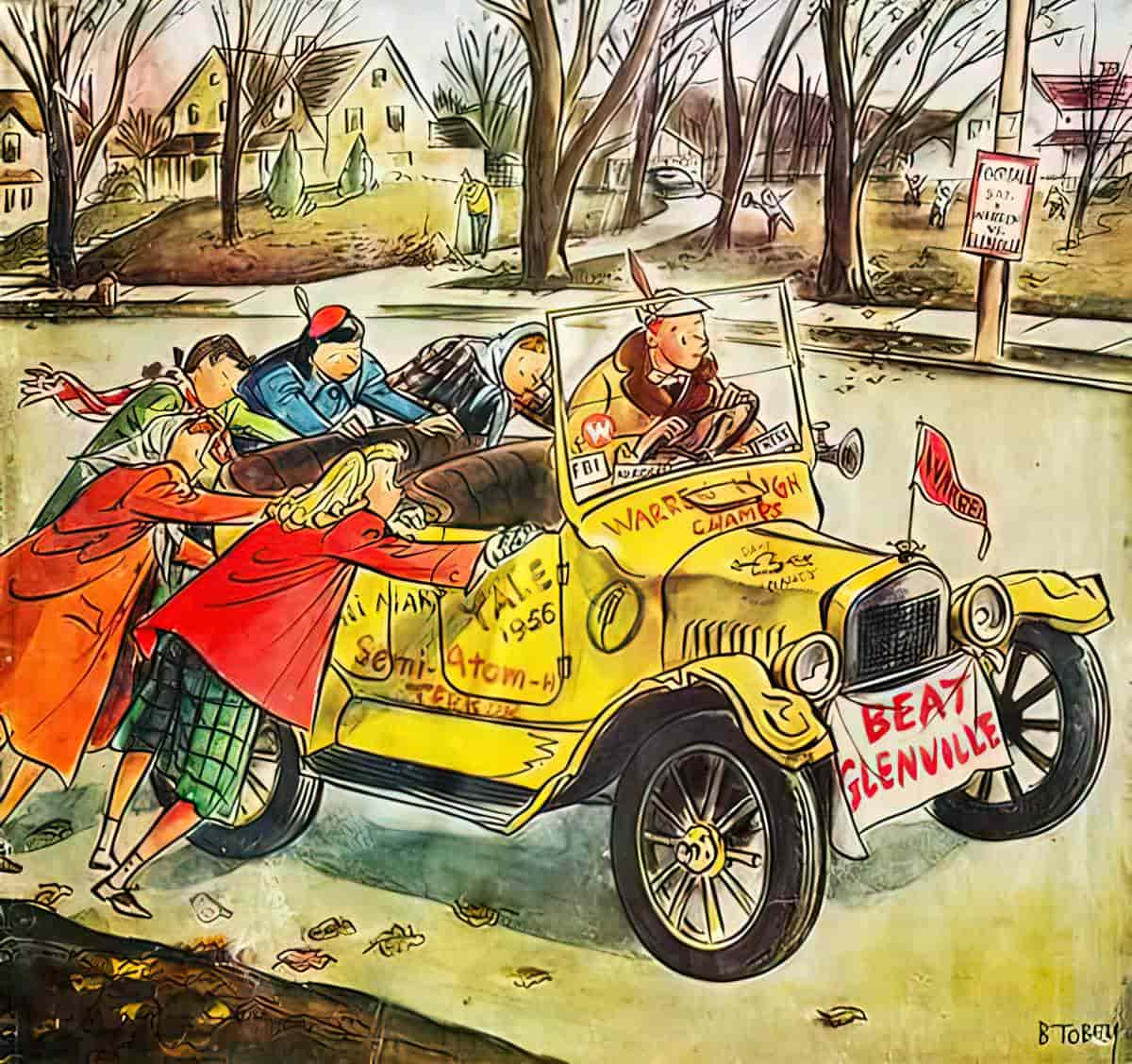

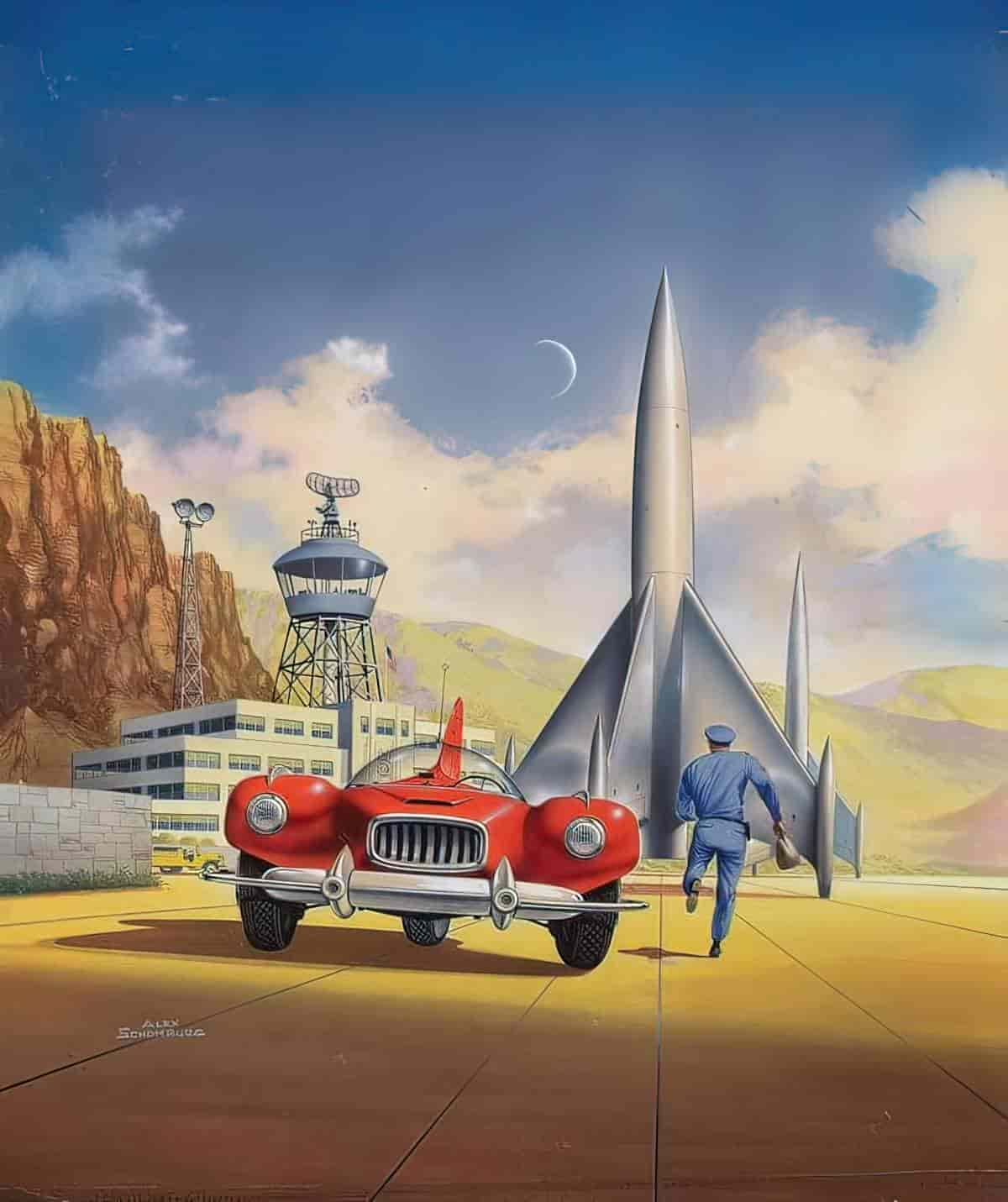

1950s

Like many things from the 1950s, the automobiles of this period symbolise “the transition from a passionate and optimistic past to a present in which technological complexity functions as a shroud for human emotion.” (Stephen Childs.) All old cars do this, but especially cars from the early 1950s.

Childs outlines the American 1950s alongside car history:

- 1950: President Truman authorized the USA to build the first hydrogen bgomb. Stalin and Mao tse Tung signed a mutual defense pact. Joseph McCarthy started his crusade against communism. The first Motorama show debuts at the New York Waldorf. Chevrolet showcased their new Powerflite transmission.

- 1951: Ford’s Ford-o-Matic

- 1952: The contraceptive pill.

- 1953: Soviets admitted to having the H-bomb. Chrysler introduced their first automatic transmission.

- 1954: Spinner hubcaps became the most popular car accessory in America. The first McDonalds fast food restaurant. President Eisenhower revealed plans for a new Interstate Highway system. The second hydrogen bomb exploded at Bikini Atoll. Elvias sang “It’s All Right”.

- 1955: US production was at a post-war high. Ford Chevrolet and Chrysler (the Big Three auto producers) dominated about 97% of the market. Disneyland opened in California. Alan Freed coined the term “Rock and Roll”.

- 1957: The USSR moved ahead in the space race with “Sputnik”. On the Road by Jack Kerouac was published. Highway deaths increased. An early vesrion of breathalyzers were tested. US automobiles realized their ‘apex of excessiveness’ (in style and horsepower). Plymouth’s Fury (a two door hardtop) is the peak example of that.

- 1959: By the end of the decade, tail fins on Fords and Mercurys had basically disappeared, though Chevrolet introduced its ‘batwing’ fins (only for a year). Cars became more compact. The Ford Falcon and the Chevrolet Corvair were released this year. Buddy Holly died in a plane crash.

The 1950s in sum:

- Emphasis on sexuality, power and wealth

- These all intersect with masculinity

- Quentin Wilson, English TV presenter and motoring journalist has called cars of the 1950s ‘bordellos’ on wheels.

- Wilson has also drawn a similarity between grille designs resembling ‘rocket launchers with 38D cups).

- Apparently tail fins were invented by Harvey Earl (on the General Motors design staff) after Earl visited a P-38 fighter. Other design features were also influenced by the jet industry e.g. the tail lights, and a rocket design log on the Hudson Hornet.

- Automatic transmissions were available, but the vast majority of 1950s cars had standard (manual) transmissions. Manly men saw manual transmissions as emasculating. This all plays into man’s need for mastery over machine. (The transmission ratio has now flipped — the overwhelming majority of modern American cars have automatic transmissions.)

- Since cars from the 1950s are massive, aeronautical and manually operated, this nostalgically takes modern drivers back to a nostalgic, minimally-technological time.

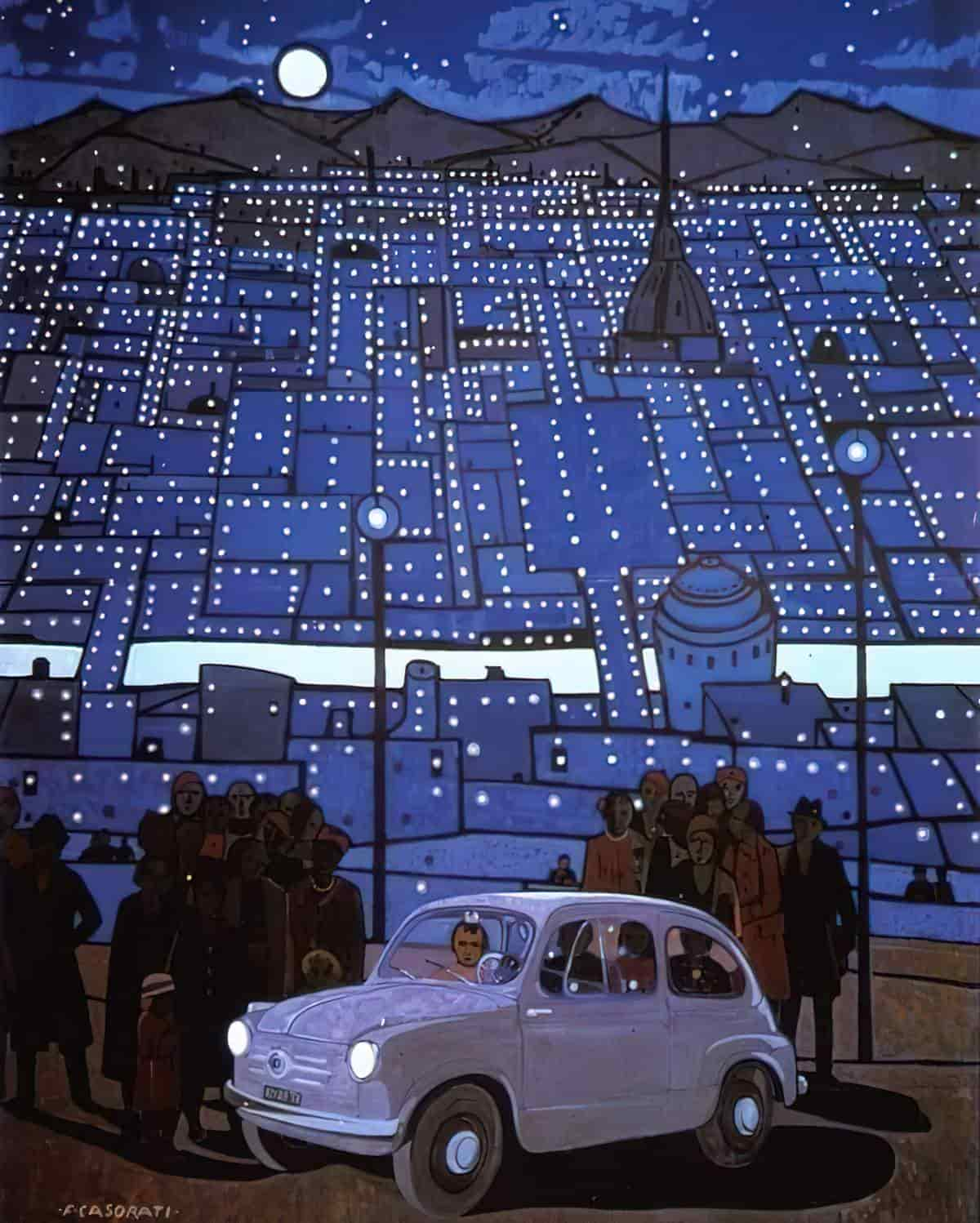

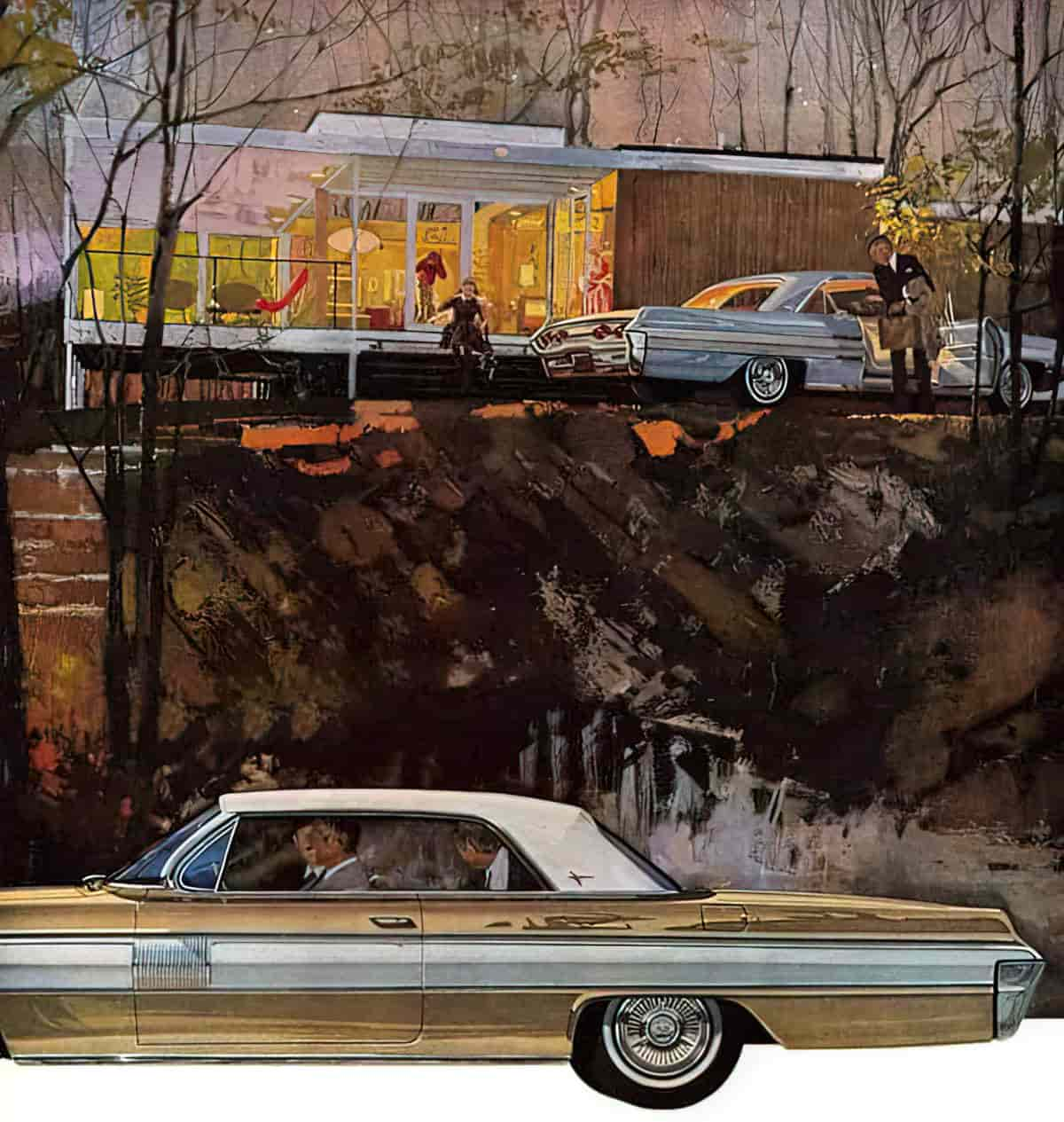

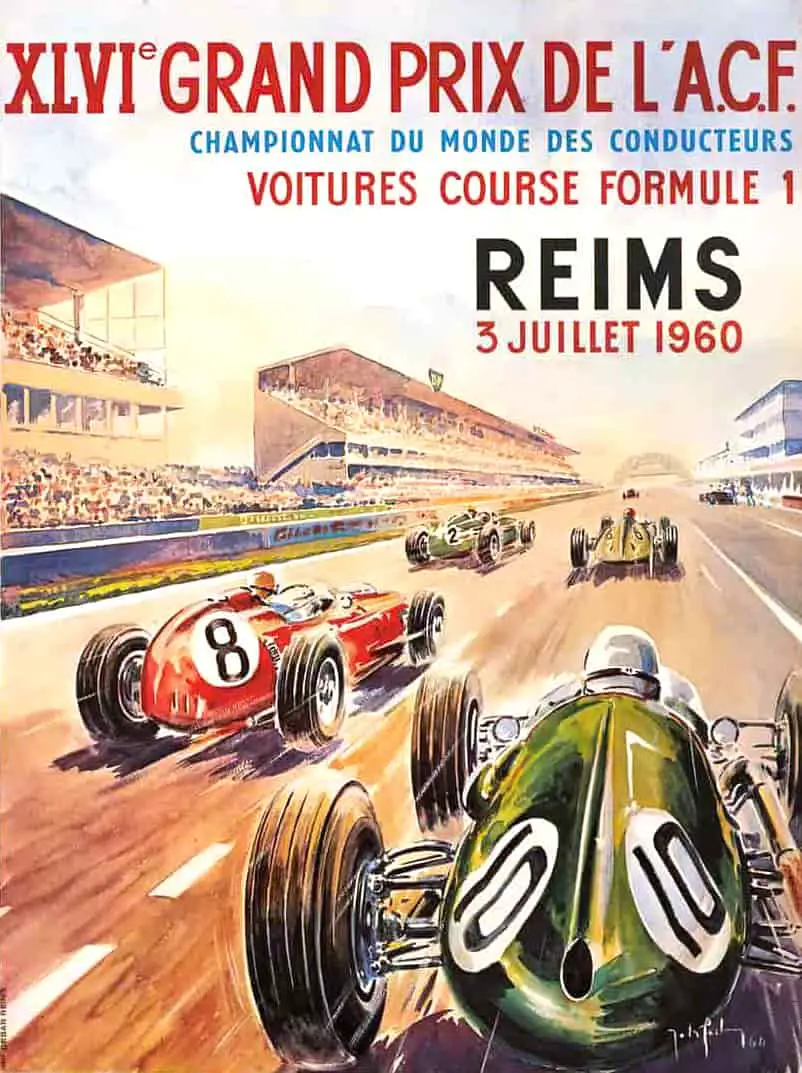

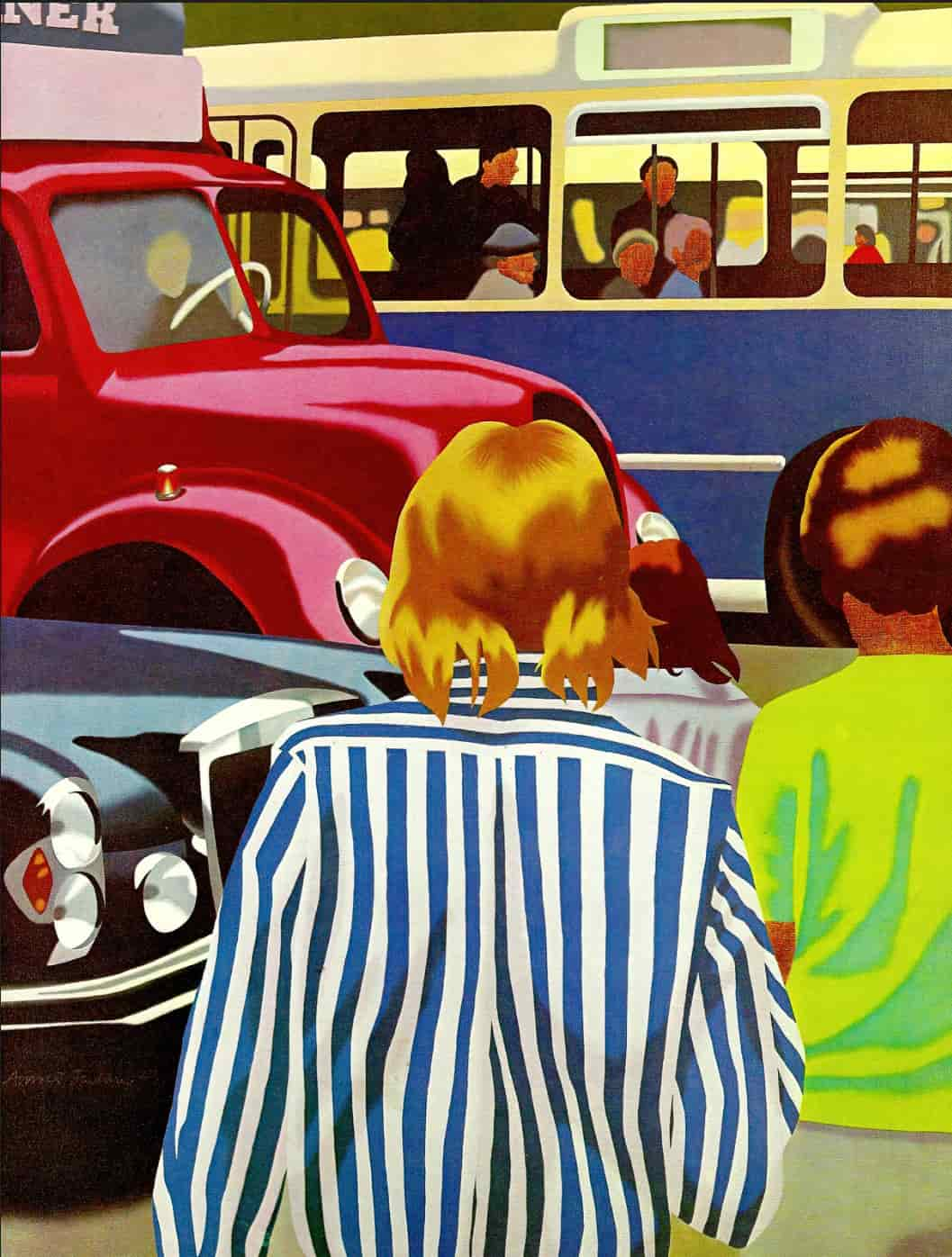

1960s

1960s

The Naughts

“Automobiles provide a logical site for exploring the connections between the means of production and social power.”

Cars are not just simple manufactured objects.

They change “the fabric of time and space”.

Still, the automobile industry has remained “a bastion of masculinity”. However, they still want to sell cars to women. This desire became apparent with Volvo’s 2004 unveiling of Your Concept Car, the first car designed entirely by women, aimed at women consumers. Tagline: “by women, for women”.

On the surface, this looks like a major step forward in the inclusion of women. But the messaging is far more ambiguous.

REPRESSIVE TOLERANCE

In 1965, Herbert Marcuse came up with the concept of “repressive tolerance”. This is when an “existing power structure fosters an apparently benign allowance of dissent. This implicit permission to differ defuses radical ideas and actions, claiming their existence as proof that the status quo is open-minded and beneficent enough to indulge such anomalies. Thus the more dissent, the more it can be co-opted as a sign that all voices are heard and no systemic changes are necessary.” In other words, discursive techniques reinforce extant relations of power while appearing to offer an escape from hegemonic forces.

the system incorporates dissent by, in effect, patting it on the head, and then using its existence to confirm how good and tolerant the status quo is. […] Tolerance now serves the purpose of providing the illusion that freedom exists in society, while political power remains in the hands of the elites.

Aune, 1994In the case of Volvo’s Your Concept Car, if you take a close look at the language of marketing, there is a frequent tendency to domesticate the women designers and consumers. Terminology “places the automobile within the realm of household activities”. This has the effect of relegating women to a so-called proper role within the home as homemakers and caretakers of others.

First, it lumps all women together in a single category by talking about “what women want”. It also turns women into the Other. (Your Concept Car — not Ours — i.e., the patriarchy.) This phrase is found frequently in the popular press coverage of the Your Concept Car.

Even the name of the vehicle keeps the car as nothing more than a concept, something shapely, to be looked at, literally positioned on pedestals in galleries alongside fashion and works of art. If art is taken seriously, that’s not a problem in itself, but when a car is deemed art, it remains nothing more than an intriguing curiosity. The marketing around the exhibitions used phrases such as “hot women designers”.

“Your car is a bit like your living room, you know.” (Tatiana Butovitscho Temm, design team member, 2004.

“The car’s chunky styling was not what we were expecting from a bunch of girls.” (Caption underneath photo of car, 2004.) This ascribes gender to the body of cars.

“As easy to clean as a nonstick frying pan”, Anna Rosen, spokesperson for the design team. This reinforces women’s role as cleaners and assumes women are interested in their roles as “designated charwoman”. (The all woman design team served as “a political palliative […] effectively used to validate the existing social and economic structure”.

Seat covers can be changed depending on a woman’s mood. Women are assumed whimsical and capricious. [“It’s a woman’s prerogative to change her mind” co-opts the language of a budding #MeToo movement.]

“Repeatedly the low-maintenance features of the car accompany references to the high-maintenance nature of women. For example, a BBC report mentions “an external filler point for washing fluid (no breaking your nails while trying to open the Bonnet”. (Top Gear, 2004)

Women require protection from dirt.

Gull-wing doors protect a woman’s modesty and allow a woman to exit her car gracefully (suggesting women need to be mindful at all times of how she appears to others).

“The design team decided early on that women preferred not to have to look under the hood.” (Women are only interested in/capable of the surface appearance of things.)

If anyone is thinking at this point, why shouldn’t women have cars designed specifically to accommodate women? The problem is, the conversation (discourse) changes. Perhaps we should be asking instead: Why is it important that a woman exit a car ‘gracefully’? Why are we assuming women are interested only in the frivolous? These assumptions reinforce sexist notions about how women essentially are and “contribute to the very social structures and forces that disadvantage them”. Instead of changing the cumbersome clothing that makes getting in and out of a car difficult, or shoes which make pedal-work dangerous, this car accommodates them.

The authors give another ridiculous (but real) example from history: fainting rooms and fainting couches into the home and hotel architecture in the early 20th century. What really needed doing was the overly-tight corsetry of the era. [Note to say that corsetry hasn’t always been a problem, but that good corsets functioned as an early form of bra.] When women removed overly tight fin de siecle corsets, due to the a fashionable 18 inch waist, they would often faint due to the air rushing into their lungs.

Notes from “A Car of Her Own: Volvo’s “Your Concept Car” as a Vehicle for Feminism? by Roy Schwartzman and Merci Decker, 2008

“Safety doesn’t sell” (to men) but car manufacturers worked out that safety is a main consideration for women, as evinced in this article:

Volvo was one of the first carmakers to really embrace safety as a selling point, something that was counter to how most carmakers saw things back in the day. Lee Iacocca, the father of the Ford Mustang, Pinto, and the man who saved Chrysler, was famously quoted as saying “safety doesn’t sell.” Maybe it didn’t sell K-Cars, but it sure as hell sold Volvos, and the Swedish carmaker really leaned into advertising that reflected this.

The Autopian

Car manufacturers continued to make condescending cars ‘for women’: “Just to clarify, by ‘woman’, they mean a consumer-group who only buys things that come in certain shades, with a low fat label, daily-routine conveniences (aka lipstick holders) and a free perfume.”

Fury over Mii, the new ‘female-friendly’ car: Volkswagen subsidiary company, SEAT, in hot water over Cosmo UK car collaboration (Which Car, 2016)

Globalizing Automobilism: Exuberance and the Emergence of Layered Mobility, 1900–1980

Why has “car society” proven so durable, even in the face of mounting environmental and economic crises? In Globalizing Automobilism: Exuberance and the Emergence of Layered Mobility, 1900–1980 (Berghahn Books, 2020), Gijs Mom traces the global spread of the automobile in the postwar era and investigates why adopting more sustainable forms of mobility has proven so difficult. Drawing on archival research as well as wide-ranging forays into popular culture, Mom reveals here the roots of the exuberance, excess, and danger that define modern automotive culture.

New Books Network

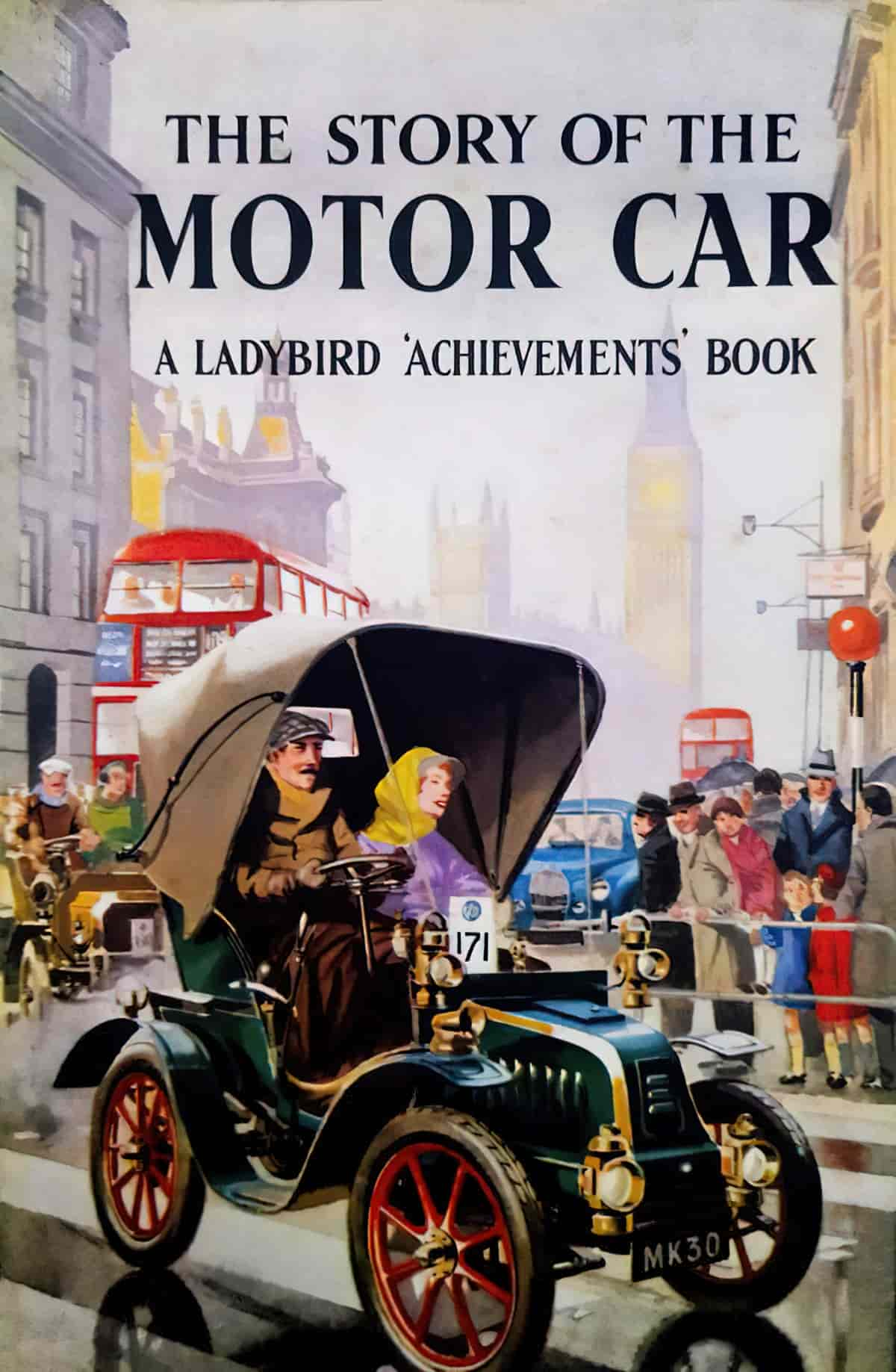

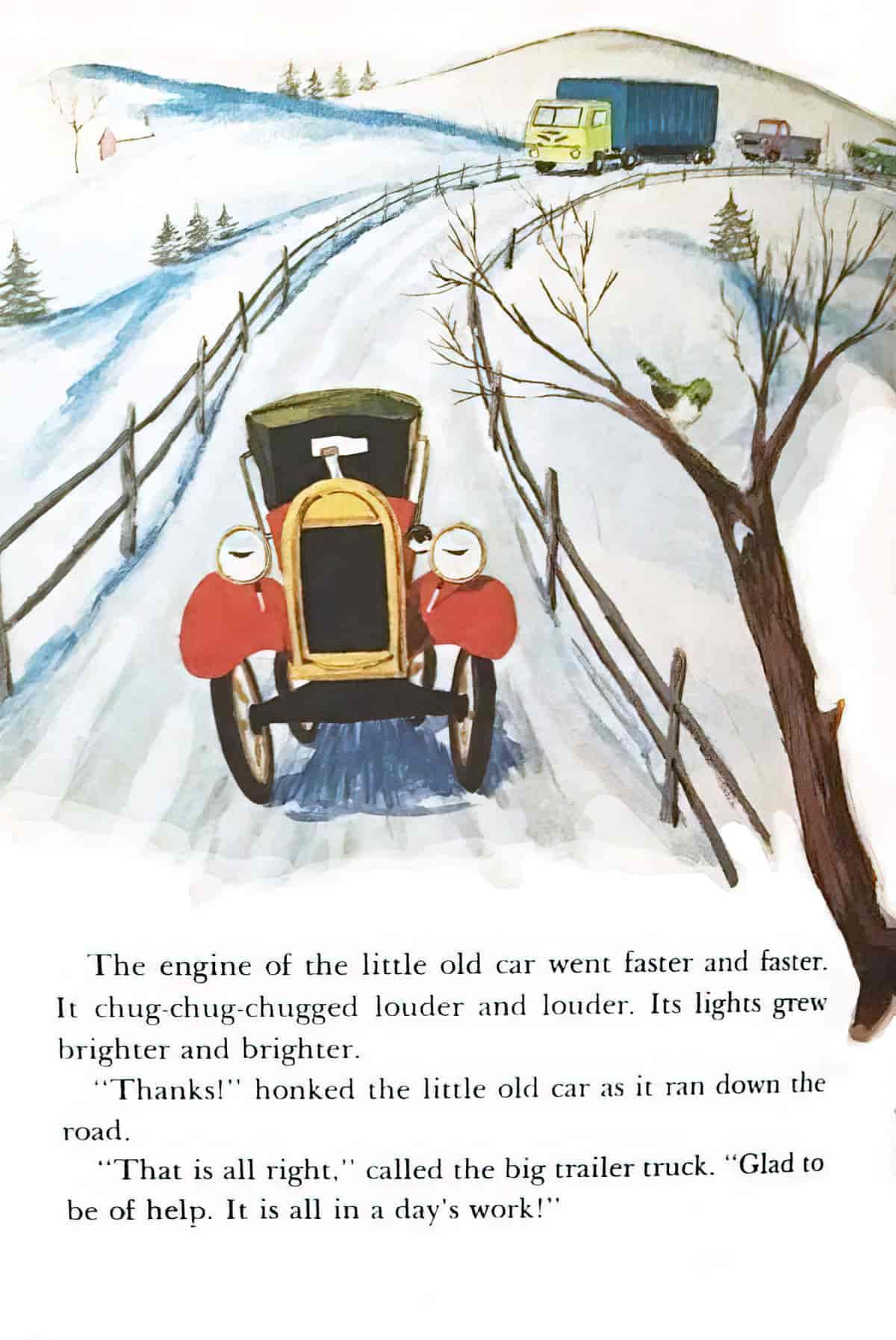

The header image is the cover of a 1962 Ladybird Book.