“A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings” by Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez is sometimes subtitled “A tale for children”. This short story reminded me of middle grade novel Skellig by British author David Almond. Sure enough, Almond has said in interview that he was influenced by the 1960 Colombian short story, and others have already looked into the relationship between the two.

- What does it mean for a short story to be ‘for children’?

- How is the story structured?

- What do I get out of this story and how are its themes relevant today?

NARRATION OF “A VERY OLD MAN WITH ENORMOUS WINGS”

Perhaps this is the thing which seems tailored for children. The narrative voice has a fairytale/folktale vibe.

SETTING OF “A VERY OLD MAN WITH ENORMOUS WINGS”

The setting is a fairytale world, but not the forests and castles of landlocked fairytale Europe — this is a fishing village beside the sea and the sea is the magical place. Weird things come out of the sea. First crabs, then, well, an old man with wings.

But why else is the sea setting important? Well, the sea and shore is often said to be a ‘liminal’ space — a space that exists on the borders, in the ‘in between’. But the word liminal is useful because it refers to metaphorical borders as well as geographical, actual ones.

A liminal space is the time between the ‘what was’ and the ‘next.’ It is a place of transition, waiting, and not knowing. Liminal space is where all transformation takes place, if we learn to wait and let it form us.

Liminal Space

Apart from the sea itself, the story arena is very small for this one — we never follow the ‘camera’ into the ocean depths. Rather, the entire story takes place around a chicken coop and shack.

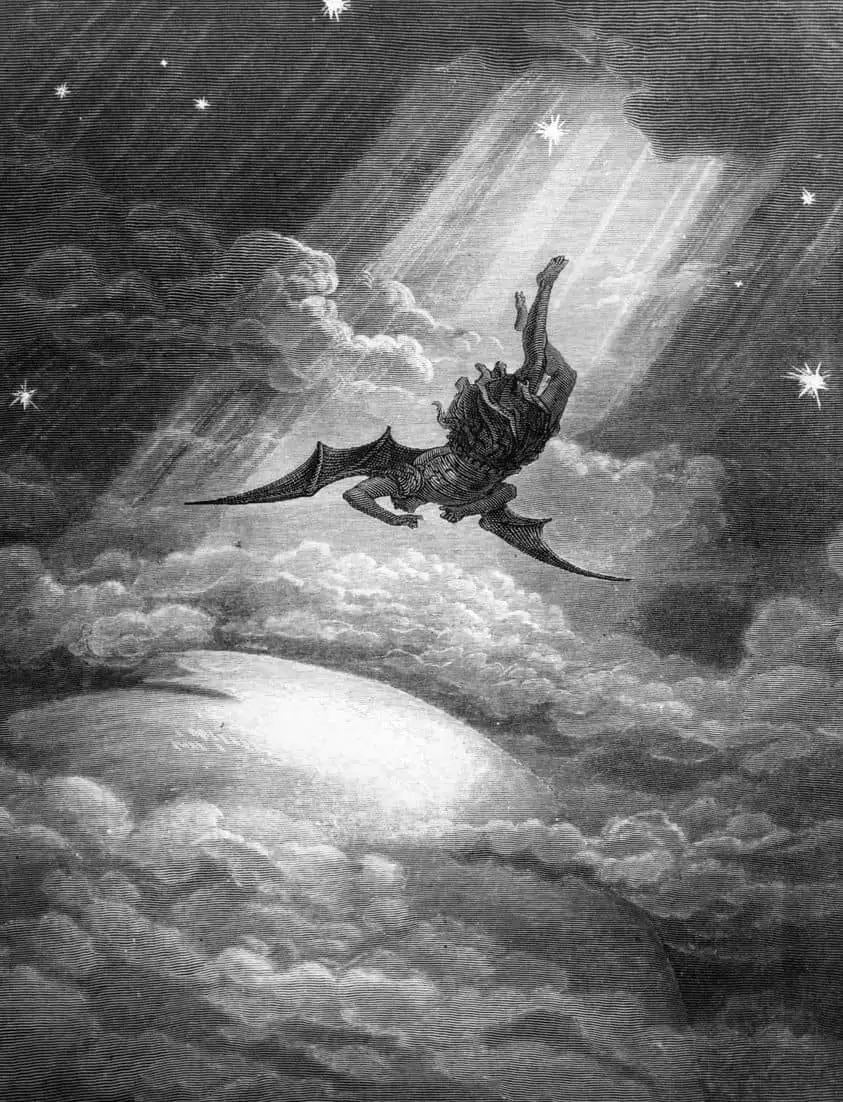

The setting is ‘fallen’ — the inverse of utopian. Also known as postlapsarian. A type of hell before actually getting to hell. ‘Sea and sky were a single ash-gray thing’, we are told. Hell on Earth, in other words. This is a story about an unfortunate convergence. The angel is both miraculous and ordinary — the world is both worldly and heavenly, with no division between the celestial and earthly.

When people come from all around to see the caged angel, broken and pathetic, this is not part of the fantasy world. Garcia Marquez is saying nothing about human relationships that hasn’t actually happened. In this way he is like Margaret Atwood, who wrote a ‘fantasy’ world for The Handmaid’s Tale, but invented nothing — every terrible thing in Atwood’s book had happened somewhere at some point in history.

Until the 20th century, it was socially acceptable to enjoy cruelty as entertainment.

Australia is having this debate, most recently with The Melbourne Cup — a culturally significant annual horse race. Many horses die as a result of this race, and their treatment too often involves torture. Australians are currently bifurcated into those who happily accept the Melbourne Cup and those who are morally appalled by it. Using history as our guide, the Melbourne Cup’s days are numbered.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “A VERY OLD MAN WITH ENORMOUS WINGS”

SHORTCOMING

“A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings” is a story about a community rather than an individual, though the story focuses on a husband and wife, which makes sense because the angel arrives at their house.

The symbolism of names is important here. Pelayo is the Spanish form of Pelagius, which if you trace back far enough means “the sea”. This character is inextricably linked to his home by the sea. Elisenda is from Catalan — originally a Visigothic name meaning Temple and Path.

DESIRE

Pelayo and Elisenda do not want a scraggy old guy with wings in their yard. That is about the last thing they need, in the wake of all those crabs. They want their baby to get well. They want to live their simple lives in peace, without calamity, without crowds turning up to their chicken coop all the livelong day.

OPPONENT

The Opposition in this story is an excellent reminder that ‘Opponent‘ does not equal ‘Villain’. The opponent in a story is the character who stands in the way of the main characters’ Desire. In this case the Opponent is very much the victim of the main (viewpoint) characters (the villagers).

The angel is guised as a ragpicker — a person who collects and sells rags. In stories, characters tend to underestimate those dressed in rags. The Pied Piper is a classic example – pied meaning he was wearing clothes stitched together by lots of different rags, meaning that he was too poor to afford proper clothes. Yet the Pied Piper had the last laugh.

Perhaps because of this history, in which a dishevelled appearance so often belies intelligence, conniving and trickery, I expected this story to end differently. I expected the fallen angel to ‘win’, to take revenge upon the people who abused him rather than helped.

The angel is presented as a classic horror genre opponent. In horror, you can’t kill the baddie. It keeps coming back, even if it’s only one arm clawing its way along the floor.

PLAN

Pelayo and Elisenda ask the woman who knows things for advice. This woman is completely full of supernatural crap, but she’s established herself as Someone Wise, and people listen to her.

We can find contemporary analogues in anti-vaxxers, astrologists, conspiracy theorists and similar. There will always be people like this in every society, who position themselves as helpers and mentors as soon as science fails to explain new and disturbing phenomena.

BIG STRUGGLE

Which part of this story is the Battle? The scenes of abuse, with the angel trapped in the cage, are of course a big struggle of sorts. For storytelling purposes, the Battle scene is the part which leads to the Anagnorisis.

This is an interesting technique: The writer spends most of the story with characters engaged in a big struggle, but the death scene is very short. The Battle which kills the angel is presented to us as succinct narrative summary rather than as a dramatised sequence.

In fact, his death is presented to us as if in passing, underscoring how little respect was garnered by this celestial creature:

Those consolation miracles, which were more like mocking fun, had already ruined the angel’s reputation when the woman who had been changed into a spider finally crushed him completely.

Why? Why not dramatise that scene for us? Wouldn’t it be spectacular, to see how a tarantula woman spiritually murders (‘crushes’) an angel? Well no, it would be grotesque.

- The story is about the relationship between the humans and the angel — the tarantula is mainly brought in as a plot device

- What I can imagine this scene looked like is probably far more fearsome than how anyone could’ve described a blow-by-blow account on the page

- Unless writing for the action and thriller genres (and adjacent), an audience probably doesn’t even want a blow-by-blow description of a crushing.

ANAGNORISIS

When even the tarantula can’t get rid of the groteque angel completely, Elisenda realises she’ll just have to live with him.

Pelayo and Elisenda very soon overcame their surprise and in the end found him familiar.

I sometimes wonder what would happen if astro-biologists discovered life on another planet. Unless it was intelligent life who was coming for us all, I suspect we’d all be surprised for a while, but that the wonder would very soon wear off and we’d return to our regular infighting here on Earth, giving extraterrestrial lifeforms very little thought on a day-to-day basis, outside a small group of enthusiasts. We’d just take it for granted that it’s there, much like we take deep sea life for granted. I rarely give a thought to the alien-like creatures living deep in the Mariana Trench. If similar lifeforms were found beneath the surface of Jupiter’s moon, Europa, I’d probably watch a documentary on it, be fascinated for a while, then go back to my day-to-day life.

Because we can’t remain in awe forever, right? Awe is not an enduring emotion. If we felt it every day, it wouldn’t be ‘awe’.

NEW SITUATION

Having made money off him, Elisenda and Pelayo will live a nice life in their nice big mansion, having put the poor creature right out of their mind.

This is an active non-noticing. I believe we in the West are pretty good at active non-noticing. Our sports shoes are made by children living in slave conditions, but we choose not think of that when we walk out of the store wearing comfy new kicks. Almost everything we buy is unethical; but to not buy it is unrealistic. It’s impossible to buy an ethical mobile phone; it’s also impossible to log in to certain Australian government websites without one.

SEE ALSO

MAGICAL REALISM

Magical realism is a phrase that crops up a lot when discussing stories concerned with the manifestation of the supernatural in the context of everyday life. Our standout example of a magical realist writer is this very guy — Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

What’s the difference between ‘fantasy’ and ‘magical realism’? A writer at The Millions puts it this way:

in magical realism the narrative is primarily interested in the village, while in fantasy the author would focus primarily on the old man, his wings, how he got them, and what his home world is like.

Worth knowing: magical realism is a contentious label to apply to work which is not Latin American. You’ll find various opinions about whether we may call non-Latin American fiction magical realism, or whether we should instead stick to, say, ‘fabulism’ to describe other work with the same attributes but set elsewhere. There’s quite a lot to this debate.

An invasion of creatures is used in another ‘magical realist’ story — one by Keri Hulme — “King Bait”. That New Zealand story is also about the base, nasty nature of humankind, in that case greed, in this case selfishness, and our ability to dehumanise what is clearly human, or equivalently sentient.

KIDS CAN SEE THINGS ADULTS CAN’T

The idea that we are surrounded by the extraordinary yet remain blind to it is a pretty common theme in picture books, in which the archetype of The (Jungian) Child is useful as a character who hasn’t lost their wonder yet, after being subjected to the monotony of life with adult responsibilities. “Children who notice things adults don’t” could be a subcategory of children’s literature in its own right. Think of all those fantasy portals, never discovered by adults, and all those fantasy creatures. Are they fantasy or real? Are they only real if we see them? What does it even mean to be ‘real’?

A well-known Australian picture book example of “children who notice things adults don’t” is The Lost Thing by Shaun Tan. A boy sees all sorts of weird machines everywhere. He even takes one home and his parents still don’t bat an eye. Commuters dressed in suits are wholly oblivious to the wonder all around them. The boy grows up and loses his ability to see these wondrous things, most of the time. But now and then he gets a glimpse of his former childish wonder.

What about in stories with no adults? Often in that case, when the author has dispatched with the adults, there’ll be a dog who can sense things the kids cannot. The kids will take the dog’s lead. The standout example from my own childhood is Timmy the dog from Enid Blyton’s Famous Five series.

Basically, the closer a character to its animalistic, unadulterated nature, the more useful they are in picking up on vibes more cerebral characters cannot. This is why, traditionally, girls have been used for this role more frequently than boys. Women give birth and menstruate and until very recently were consistently either giving birth or preparing to, across their entire adult lives. So women were more clearly ‘animal’ than men, who traditionally positioned themselves, and only themselves, closer to God. For 1000 odd pages on that idea see Women, Men and Morals by Marilyn French.

Header photo by Raphael Bick