The word ‘utopia’ means different things to different people and even comes from two different words. In modern English, we colloquially use ‘utopia’ to mean our own version of a perfect society. Philosophers go deeper. For example, Nassim Nicholas Taleb defines a utopia as a society built according to some blueprint of what “makes sense”.

For my purposes, utopian stories are those which create a myth of childhood by describing it as a Golden Age.

Depictions of utopia have a long history. Medieval comic genres depicted worlds of abundance and enjoyment, at least for the male characters.

FEATURES OF UTOPIAN CHILDREN’S STORIES

Maria Nikolajeva lists the main qualities of the Utopian category that most researchers agree upon in her book From Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature:

- the importance of a particular setting

- autonomy of felicitous space from the rest of the world

- a general sense of harmony

- a special significance of home

- absence of the repressive aspects of civilisation such as money, labor, law or government

- absence of death and sexuality

- and finally, as a result, a general sense of innocence

Utopian stories tend to be set in the country and the weather is usually sunny and temperate, unless there’s a storm to symbolise someone’s state of emotion (pathetic fallacy). The setting is often secluded/walled, and this wall provides both security and restriction to push back against. Inside the boundary is the world of the child; outside is the adult world. Characters/readers never worry about where food comes from (there is an inexhaustible supply); same for money. Death and sexuality are entirely absent. In The Wind In The Willows, every single character is male; in Little Women, the story is heavily female. In a pre-homosexual time (ie. where the concept doesn’t exist for children) sexuality therefore never crops up. In general, this is a time of innocence, where characters are oblivious to world politics, intellectual debate and so on.

In utopian fiction there is a transformation of a spatial concept, like a garden, into a temporal state, childhood.

EXAMPLES OF UTOPIAN STORIES

A Goodreads List of Utopian Fiction includes books for all ages, but includes children’s fiction commonly cited as Utopian such as:

- The Hobbit

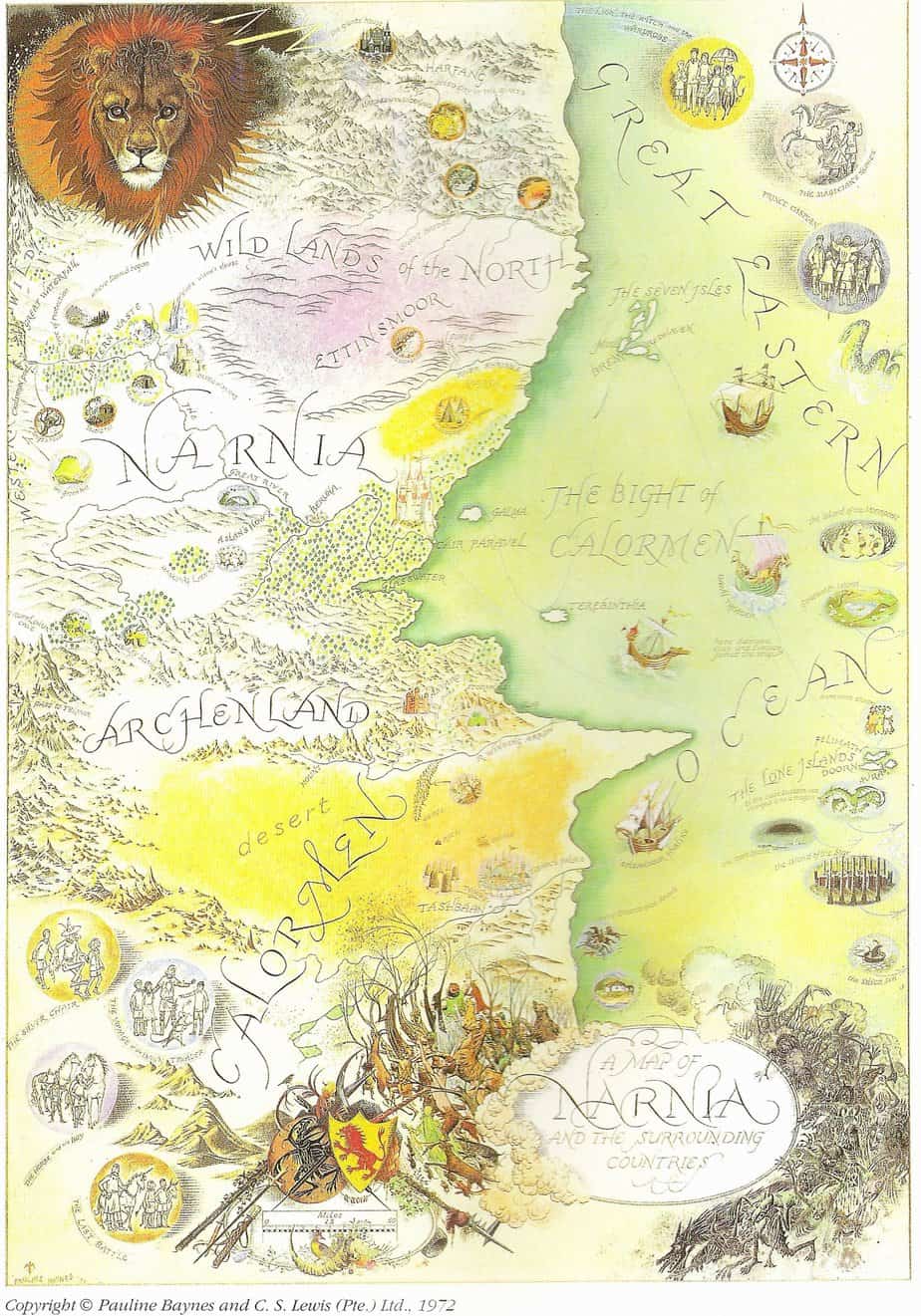

- The Chronicles of Narnia

- The Secret Garden

We sometimes find a utopian (or partially utopian) setting in stories for adults and young adults. (Though it is far more common to find an ‘snail under the leaf setting’, in which everything looks fine, but we know that just beneath the surface we’ll find death and deception.) Utopian stories for adults are quite likely to star female main characters.

- Suburgatory — this is a comedy set in a fictional American suburb, where horrible things happen (have happened) but where we know that even the ‘mean girls’ are really quite benign. The smartest character is our NYC savvy teen.

- Nashville — There are definitely utopian characteristics of this show, in which the only side of Nashville we see is the cool music scene. We don’t see true poverty. We see political corruption, but overall the audience is invited to join a romanticised musical world. Sinners are punished for their sins.

- Orange Is The New Black — a fairly romanticised view of a women’s prison.

- Waitress — any show which has a small town, and an eatery at its heart, is likely to be utopian in nature. If not set in the 1950s, there will probably be 1950s nostalgia.

- Downton Abbey — Though class inequality is ostensibly part of the plot, it’s a cosy sort of conflict.

Utopian film and TV shows tend to get rated lower on IMDb than snail under the leaf settings, which are obviously more interesting to many viewers. However, there is definitely a place for true utopian stories as they provide an escape.

Children’s stories commonly cited as Utopian:

- Little Women — home is a safe refuge. The March sisters may consider themselves poor but they’re not really.

- Little House On The Prairie series — This was the Wild West, where death was everywhere. Compare the real life of Laura Ingalls-Wilder with her utopian, mostly fictional retelling. Western stories for adults these days are almost all anti-Westerns, but Little House On The Prairie is a utopian Western setting.

- Beatrix Potter’s stories — The imagery of Beatrix Potter’s world balances a colonised, accomplished horticulture and agriculture. Nature is stable but mysterious, and lies untamed beyond the garden wall. (Inglis)

- Anne of Green Gables — the character starts with an almost perfect place (Marilla and Matthew’s homestead) and makes it still more perfect (Nodelman). An adult (Marilla/Mathew) is liberated by a child.

A huge cherry-tree grew outside, so close that its boughs tapped against the house, and it was so thick-set with blossoms that hardly a leaf was to be seen. On both sides of the house was a big orchard, one of apple-trees and one of cherry-trees, also showered over with blossoms; and their grass was all sprinkled with dandelions. In the garden below were lilac-trees purple with flowers, and their dizzily sweet fragrance drifted up to the window on the morning wind.

Below the garden a green field lush with clover sloped down to the hollow where the brook ran and where scores of white birches grew, upspringing airily out of an undergrowth suggestive of delightful possibilities in ferns and mosses and woodsy things generally. Beyond it was a hill, green and feathery with spruce and fir; there was a gap in it where the gray gable end of the little house she had seen from the other side of the Lake of Shining Waters was visible.

Anne of Green Gables, Chapter 4

- Swallows and Amazons series by Arthur Ransome – while the father is at war, the children engineer their own low-stakes mini-war with a couple of harmless little girls.

- Winnie-the-Pooh by A.A. Milne — by the time these stories were written there was no longer any large acreage ‘wood’ left in England. It would have been impossible to really get lost!

- Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland — although this world is full of quirky characters we know no real harm will come to Alice.

- The Wind In The Willows — the ever happy riverbank is childhood and the perhaps Wild Wood is adolescence/adulthood.

Leaving the main stream, they now passed into what seemed at first sight like a little land- locked lake. Green turf sloped down to either edge, brown snaky tree-roots gleamed below the surface of the quiet water, while ahead of them the silvery shoulder and foamy tumble of a weir, arm-in-arm with a restless dripping mill-wheel, that held up in its turn a grey-gabled mill-house, filled the air with a soothing murmur of sound, dull and smothery, yet with little clear voices speaking up cheerfully out of it at intervals. It was so very beautiful that the Mole could only hold up both forepaws and gasp: “O my! O my! O my!”

The Wind In The Willows

Sometimes cited as Utopian:

- Julie Of The Wolves

- the Green Knowe books by Boston and Boston

- several books by William Stieg

Based on Nikolajeva’s list above, I would include from my own reading/viewing:

- The Children of Cherry Tree Farm and Shadow the Sheep Dog by Enid Blyton, among others, because the setting of most texts identified as idyllic is rural, and the characters’ closeness to nature is accentuated. Blyton was a big proponent of introducing the country life to city and suburban children, at least in their fiction. Her characters tend to move from the city to the country in order to have fun. City children are less virtuous than country children, personified clearly by the difference between Connie and Joe/Bessie/Fanny in Folk Of The Faraway Tree.

- Kiki’s Delivery Service — Anne of Green Gables is very popular in Japan, with the cover translated as ‘Red-haired Anne’. This is borne out by the fact that the percentage of tourists to Prince Edward Island is disproportionately Japanese. Kiki’s Delivery Service is a much more modern story, with a setting used numerous times by Hayao Miyazaki — a wholly imagined place which looks part pre-war European and part Japanese. Does this mean that Utopian stories tend to do particularly well in Japan? According to a paper by Koon-ki Ho, ‘many scholars deny the existence of a utopian tradition in the East and their conviction is strongly supported by the absence of a kind of state romance, as Thomas More’s Utopia, in which the main purpose is the portray an ideal society achieved by socio-political planning, which can be called literary planned utopia or planned utopia in fiction’. Japan has even less of a utopian tradition than, say, China, and it can be argued that Utopian Literature in Japan was introduced by the West. The rest of the paper goes on to clarify that traditional Japan is not entirely free of the idea of ‘paradise’ (often coming in folktales via China), but that ‘satirical utopias’ and ‘planned utopias’ are definitely a Western introduction. Science fiction dystopias are also very big in Japan, but could it be true that utopian stories do particularly well in Japan?

- Gilmore girls — This show exists on the Utopian spectrum. Here we have an insulated community where poverty does not really look like poverty (Lorelai Gilmore always has enough money for ice-creams, which she can then discard in a rubbish bin if she decides she doesn’t want it.) Even when Rory gets sentenced to community service, she finds her niche and ends up rather enjoying it. Sex is absent (or off-screen) — instead, what we’re shown is romance. The grandparents are very rich. Their house forms both a refuge and a barrier against which both Lorelai rebels. Rory goes from one cloistered environment to another when she gets into her Ivy League university. As soon as Rory is about to leave the Utopia, the series ends. When there is death, the death is treated in comical fashion — we have the person who owns the inn that Lorelai and Sooki want to buy; we have Paris’ elderly man-friend, which is comical because the entire persona of Paris is a caricature. As in many utopian stories for children, there is an underclass of laborers/cooks/cleaners working behind the scenes. Ostensibly, Lorelai Gilmore has worked her way up from this, and this is considered a prequel-worthy triumph.

TERMS SIMILAR TO ‘UTOPIAN’

Arcadian — Another word for Utopian. Arcadia is the name of a Greek province. Utopia also comes from Greek and literally means ‘nowhere/not a place’, though this might be a somewhat simplified etymology. But in some ways, Arcadia and Utopia are opposites — Arcadia is thought of as a garden full of good fruits for humans to enjoy whereas Utopia can be considered a place which has been shaped by humans, in which the environment is as much a construction as the society itself. Utopia in its purest form is a spaceship in a futuristic science fiction story.

Edenic, Edenlike — the adjective form of Eden, from the Bible.

Elysium — A Greek conception of the afterlife, reserved for mortals who were related to the gods and other heroes. In Elysium they would live a blessed and happy life, indulging in whatever employment they had enjoyed in life.

Locus amoenus — (Latin for “pleasant place”) is a literary topos involving an idealized place of safety or comfort. A locus amoenus is usually a beautiful, shady lawn or open woodland, or a group of idyllic islands. A locus amoenus will have three basic elements: trees, grass, and water.

Nostalgic — can have a negative connotation, meaning a kind of ‘homesickness’, where nothing can ever be as good as you think it was (and it never was that great anyway).

Pastoral — when referring to land, it means land for raising cattle or sheep. But when referring to literature, pastoral means ‘portraying an idealized version of country life. But if you look for ‘pastoral books’ you’ll probably find books relating to the Christian church. The Wind In The Willows is pastoral, though also treated as nostalgic and Arcadian, depending on the critic.

Prelapsarian — characteristic of the time before the Fall of Man; innocent and unspoilt. (The opposite is postlapsarian, or dystopian.) Writing for The Spectator, Toby Young describes Harry Potter as ‘prelapsarian’: “What is Hogwarts, after all, but an idealised version of an English public school, with its houses, quadrangles and eccentric schoolteachers? […] Rowling is often criticised for lifting many elements from classic children’s literature, but the book I was reminded of when I read Harry Potter to my daughter was Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited. I don’t just mean the glamorised portrait of upper-class, English education. In addition, there’s the romantic longing for a prelapsarian aristocratic society, an England uncontaminated by bungalows and privet hedges.”

Topophilia — this is a term coined by Gaston Bachilard in his book The Poetics of Space. It means simply ‘love for a place’, free of the negative connotations associated with ‘nostalgia’.

COLLECTIVE PROTAGONISTS IN IDYLLIC/UTOPIAN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

Idyllic texts, to a much higher extent than other fiction, make use of a collective protagonist. Paradise is a collective experience; it can only be enjoyed together with a group of soulmates. But this is just one aspect. Idyllic narratives very seldom go beyond the superficial rendering of events; no internal life of the characters is portrayed. For such an external narrative, a collective protagonist offers vast possibilities.

Significantly, collective protagonists are a typical feature of children’s fiction in general, while they rarely appear in adult fiction, outside the purely experimental novel. There may be several reasons for this. Collective protagonists supply an object of identification to the readers of both [all] genders and of different ages. Collective characters may be used to represent more palpably different aspects of human nature; for instance one child in a group may be presented as greedy and selfish, another as carefree and irresponsible, and so on. Basically, a collective protagonist is an artistic device used for pedagogical purposes.

Maria Nikolajeva, From Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature

Each entity in a set of protagonists represents a different part of the child reader.

In Little Women we see four ‘entities’ and each represents specific traits:

- Beth = pretty, nice, shy, peace-maker, always content with her fate.

- Meg = complaining, elder-sisterly, envious.

- Amy = spoiled, vain, concerned about her looks, suffers most from being poor, longs most for nice clothes.

- Jo = hot-tempered, different, singled out by the author for the sequel, is a reflection of the author. Jo’s traits only become promiennt because they are presented against the background of the three other sisters.

The collective protagonist of Little Women loses its wholeness when Meg is taken away.

In The Wind In The Willows we have:

- Rat = practical, intelligent, loyal, affectionate, fully content with his life.

- Mole = the naive, curious, enthusiastic part of the child, very much home bound

- Badger = the most grown-up part, on the verge of adolescence

- Toad = the adventurous and anarchistic part of the child (the Jo March counterpart)

In the Famous Five series we have:

- Julian = responsible, elder-brotherly, almost avuncular

- Dick =Dick is the joker of the group, but also very thoughtful.

- Anne = girly, frightened, in need of protection, housewifely, domesticated

- George = (also like Jo in Little Women), George is hot-tempered, seems like the main character and is perhaps a reflection of the author.

The reason for a set of characters who form a ‘collective protagonist’ is so that a child’s ‘inner struggle’ can be depicted without adult intervention. In none of the cases above to adults step in to tame the wildness in the Jo/Toad/Georgina characters — the regulation comes from the other children in the group.

ANIMAL UTOPIAS

Animal fantasies that banish people usually have this happy, idyllic quality that human intrusion would quite spoil. They exist in worlds that are better, simpler, truer, more innocent than the human one. One longs to enter such places, but by their very nature, one never can. The Edenlike world can be suggested in various ways. It may be a place that is, as in mouse stories, existing all the time just out of sight or reach or notice. It may be a place that reverses the usual order of importance so that humans are at the bottom of the scale and animals at the top, so that though men may be present, they are hardly noticeable. Lastly, it may make its animals so human that they take over all the better human characteristics, only adding animal strangeness and animal innocence.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

Invented Edens have never been equally shared between animals and men until the decline of religious belief and man’s displacement as the centre of the universe. It is ironic that the most memorable of such places is Narnia, a land that is under the power of Aslan, the Christian Lion. C.S. Lewis only manages this pleasing arrangement by putting the action outside the earth and into a parallel world (The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe) or on Mars, where animal and human sharing is even more marked, in Out of the Silent Planet, Mars, or Malacandra, reduces thee humans to animal status; Narnia raises the animals to human heights by turning them into Talking Beasts.

Animal Land, Margaret Blount

Related

Imagining the Kibbutz: Visions of Utopia in Literature and Film (2015)

In Imagining the Kibbutz: Visions of Utopia in Literature and Film (The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2015), Ranen Omer-Sherman, a professor at the University of Louisville, looks at literary and cinematic representations of the kibbutz, what he calls the world’s most successfully sustained communal enterprise. Complementing historical works on the kibbutz, Omer-Sherman explores how the kibbutz is depicted in novels, short fiction, memoirs, and films by both kibbutz “insiders” and “outsiders” to reveal an underlying Israeli tension between the individual and the collective.

New Books Network

Utopia in the Age of Survival: Between Myth and Politics (2021)

Utopia in the Age of Survival: Between Myth and Politics (Stanford UP, 2021) makes the case that critical social theory needs to reinstate utopia as a speculative myth. At the same time the left must reassume utopia as an action-guiding hypothesis—that is, as something still possible. S. D. Chrostowska looks to the vibrant, visionary mid-century resurgence of embodied utopian longings and projections in Surrealism, the Situationist International, and critical theorists writing in their wake, reconstructing utopia’s link to survival through to the earliest, most radical phase of the French environmental movement. Survival emerges as the organizing concept for a variety of democratic political forms that center the corporeality of desire in social movements contesting the expanding management of life by state institutions across the globe.

Vigilant and timely, balancing fine-tuned analysis with broad historical overview to map the utopian impulse across contemporary cultural and political life, Chrostowska issues an urgent report on the vitality of utopia.

New Books Network

DISABILITY AND UTOPIA