An urban legend is typically told as a true story. These stories are not true at all, but often have a factual basis. They may begin with a real incident, but they may entirely fictional. They share similarities with tall stories.

Urban legends gratify our desire to know about and to try to understand bizarre, frightening, and potentially dangerous or embarrassing events that may have happened.

Brunvand, 1981

Urban legends envision humans as vulnerable in a familiar setting which is eventually revealed to be a horrifying entrapment.

Like fairy tales, they don’t require narrative logic. (Don’t interrogate whether events are possible or not; listeners are required to simply accept it happened, however unlikely.)

Famous Examples of Urban Legends

- “The Hook” — a maniac with a hook for a hand terrorises a young couple parked in a lover’s lane.

- “Deep-fried Rat” — sold at a fried-chicken franchise

- “The Choking Doberman” — swallows a burglar’s fingers

- “Beehive Spider” — told when beehive hairdos were in fashion, a young woman dies from the bites of black widow spiderlings that hatch inside her bouffant

- “Bloody Mary” — a woman who was once supposedly executed for being a witch and who will show her face in the mirror if you call on her.

- “The Vanishing Hitch-hiker” — a man picks up a hitch-hiker one night on a lonely back road but the hitch-hiker disappears from the back seat.

- “Gang Initiation” — as part of an initiation, gang members drive at night without headlights, then pursue and shoot occupants of any car which flashes them a warning.

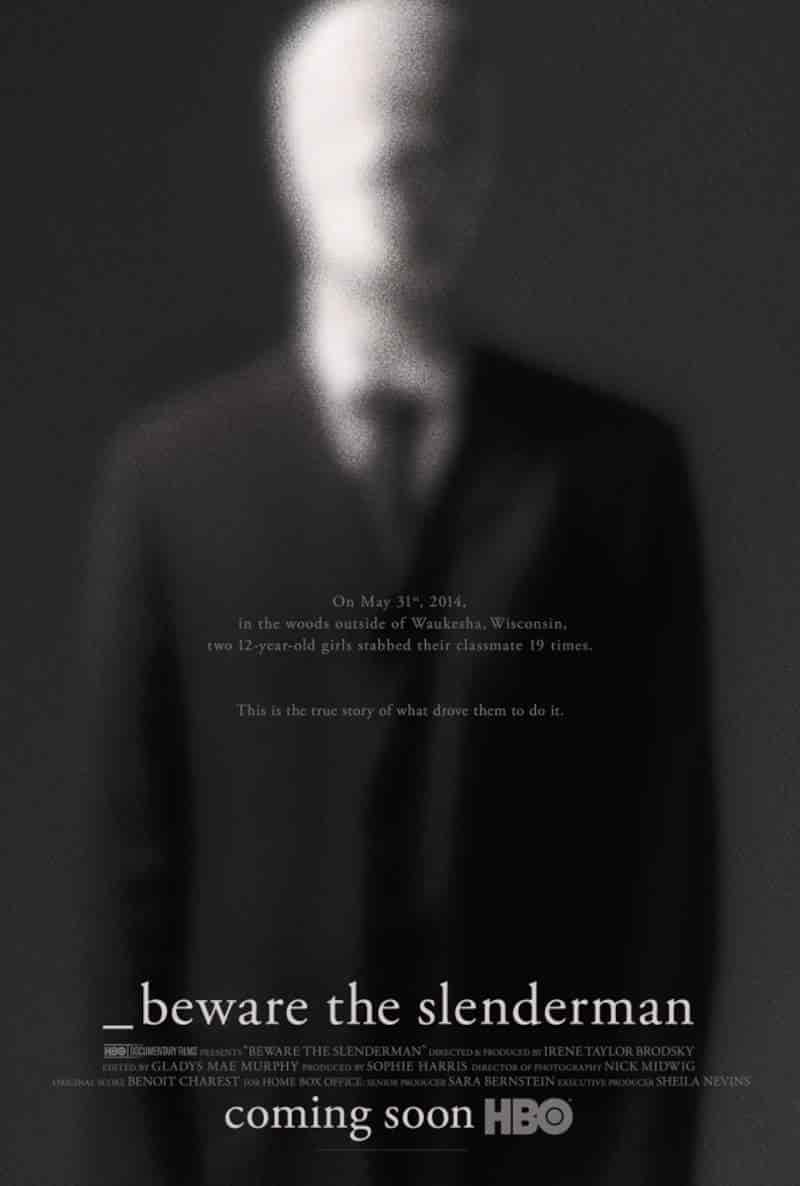

- “Slender Man” — a creepy character hangs around in forests and stalks children

Birth of an Urban Legend: The Slender Man

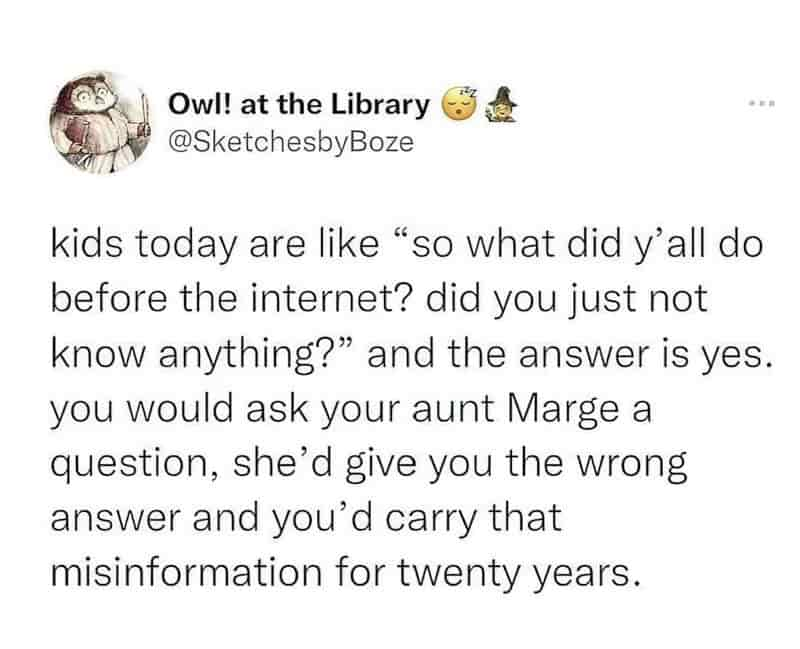

The Internet has created a renewed vector for urban legends. Because the Internet documents a trail of evolution, we know the “Slender Man” urban legend originated in 2009. As a Photoshop challenge, participants of a forum edited photographs of everyday objects to make them appear paranormal.

Slender Man has now become a part of pop culture, featuring in games, novels and film.

In an example of how fiction serves to both reflect and affect the real world, the Slender Man urban legend character inspired two 12-year-old Wisconsin girls, arrested after stabbing their friend 19 times in the woods in 2014. The stated motive? To ‘earn favour’ with the Slender Man.

There is now a 2016 HBO documentary about this crime: Beware the Slenderman.

It is a rare event indeed to be present at the birth of a Folklore motif or symbol and see it enter into a cultural environment. Is that what we are seeing with Slender Man? Andrea discusses her work and research on the subject.

The Kiss of Death: Contagion, Contamination, and Folklore

Disease is a social issue and not just a medical one. This is the central tenet underlying The Kiss of Death: Contagion, Contamination, and Folklore (Utah State University Press 2019) by Andrea Kitta, Associate Professor in the English department at East Carolina University, examines the discourses and metaphors of contagion and contamination in vernacular beliefs and practices across a number of media and forms. Using ethnographic, media, and narrative analysis, chapters discuss the changing representations of vampires and zombies in popular culture, the online discussions of Slenderman in relation to adolescent experiences of bullying, the misogyny embedded in legends about kisses that kill, and the racialized nature of patient-zero narratives that surrounding the spread of things like ebola, and the ways in which the HPV vaccine to homophobia. Issues like tellability and the stigmatized vernacular loom large throughout. Although folklorists will already recognize the social importance of vernacular narrative and belief, The Kiss of Death also shows how medical professionals have often failed to take vernacular forms into account. Through attention to narrative and vernacular belief, folklorists can model new forms of engaging with public health professionals and local communities.

New Books Network

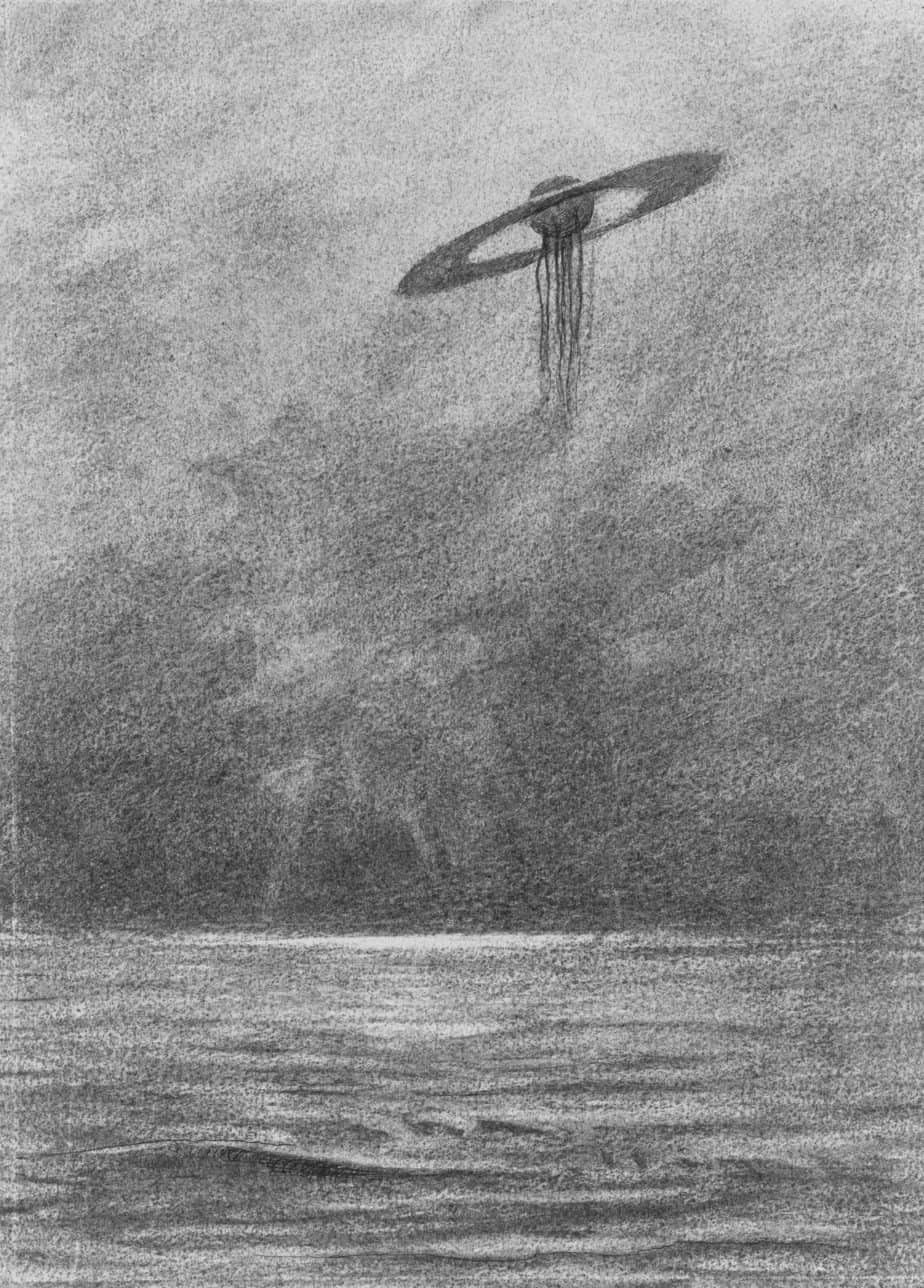

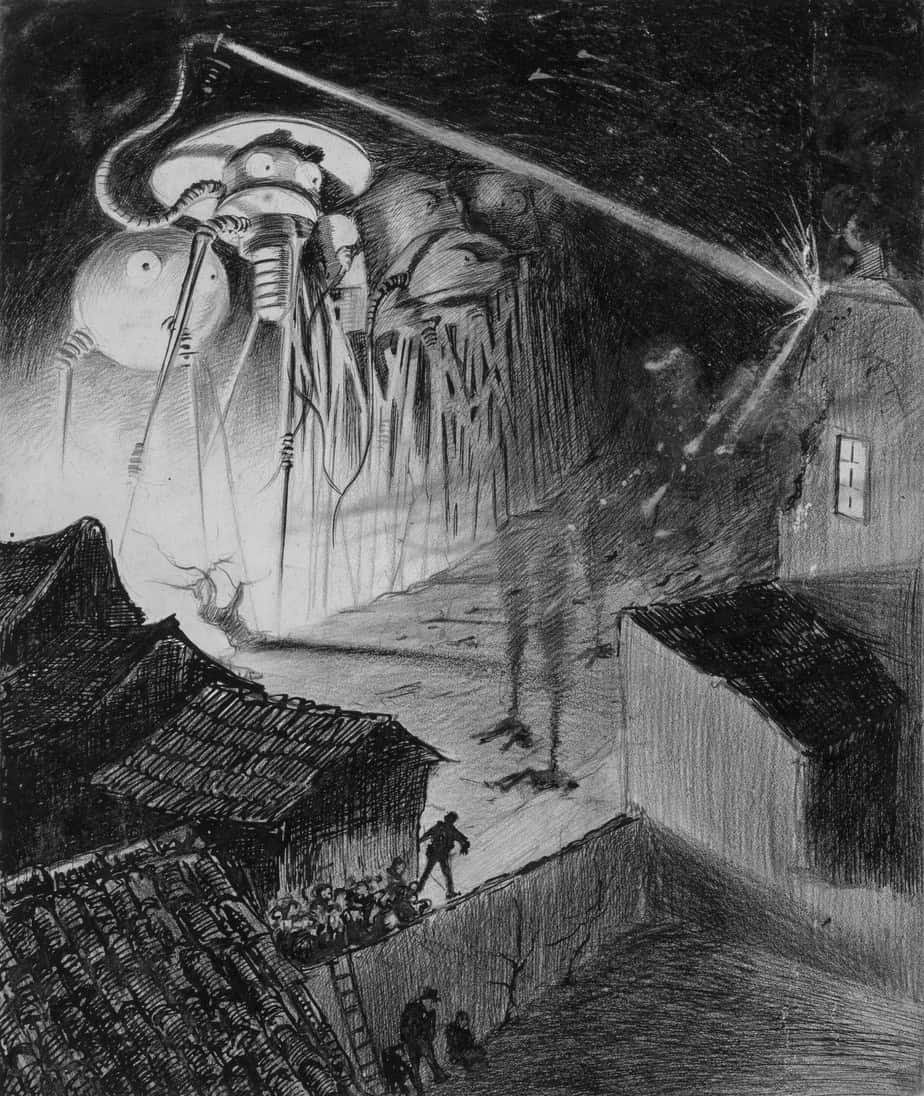

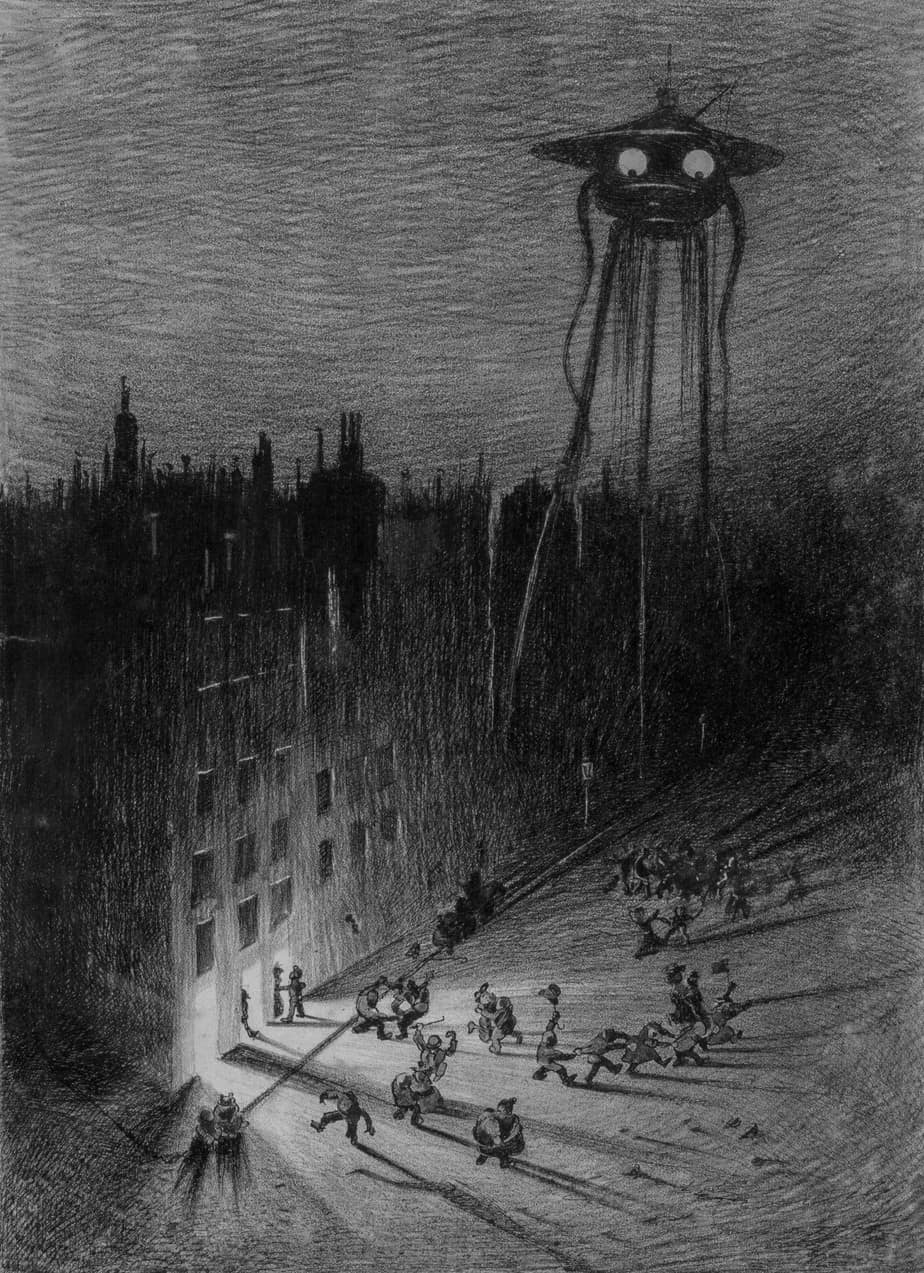

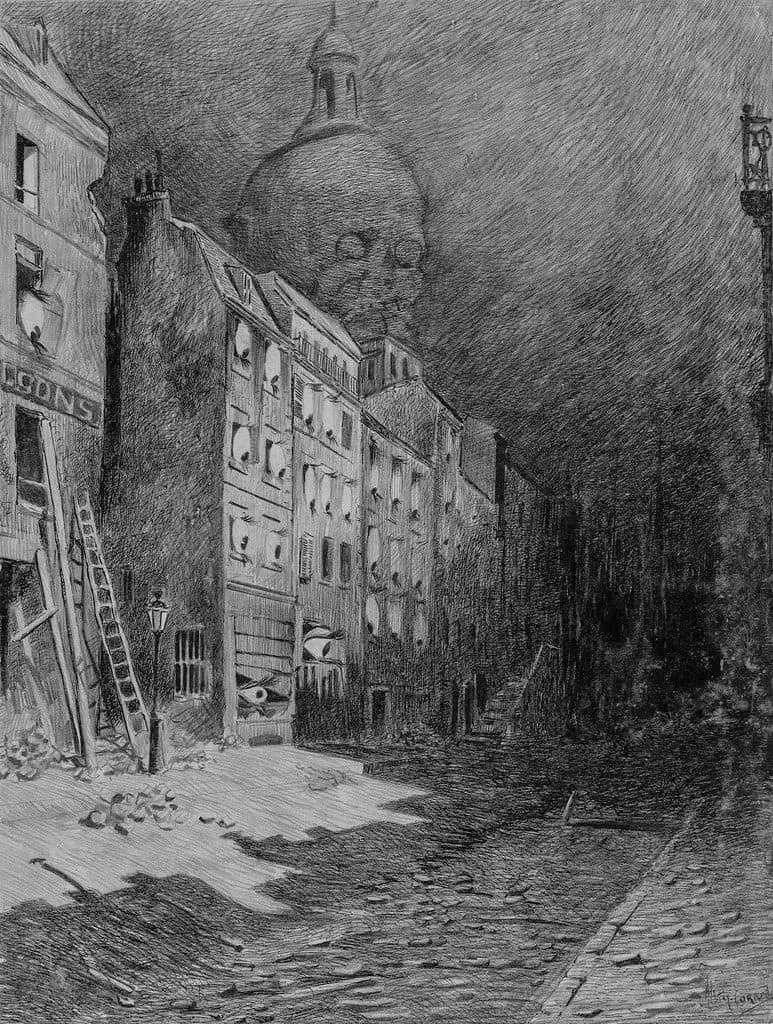

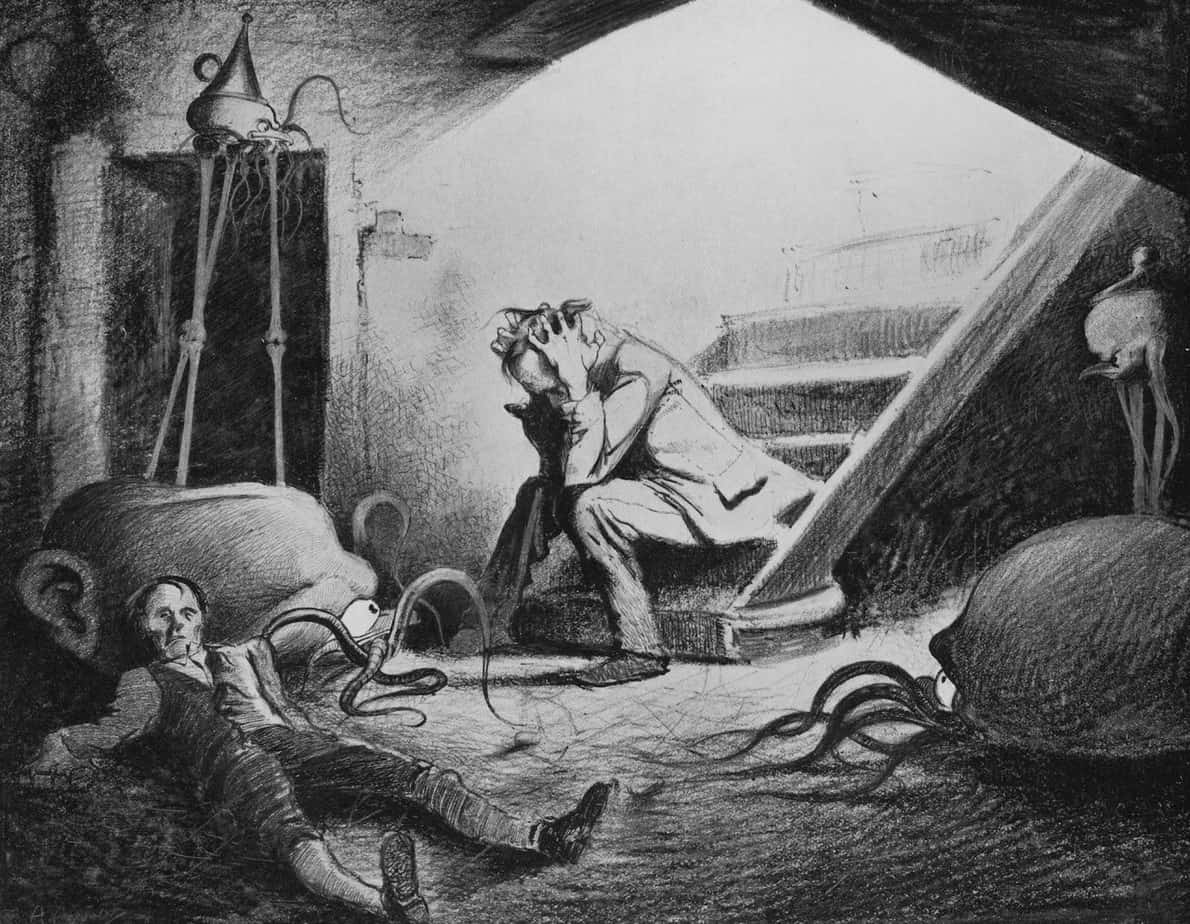

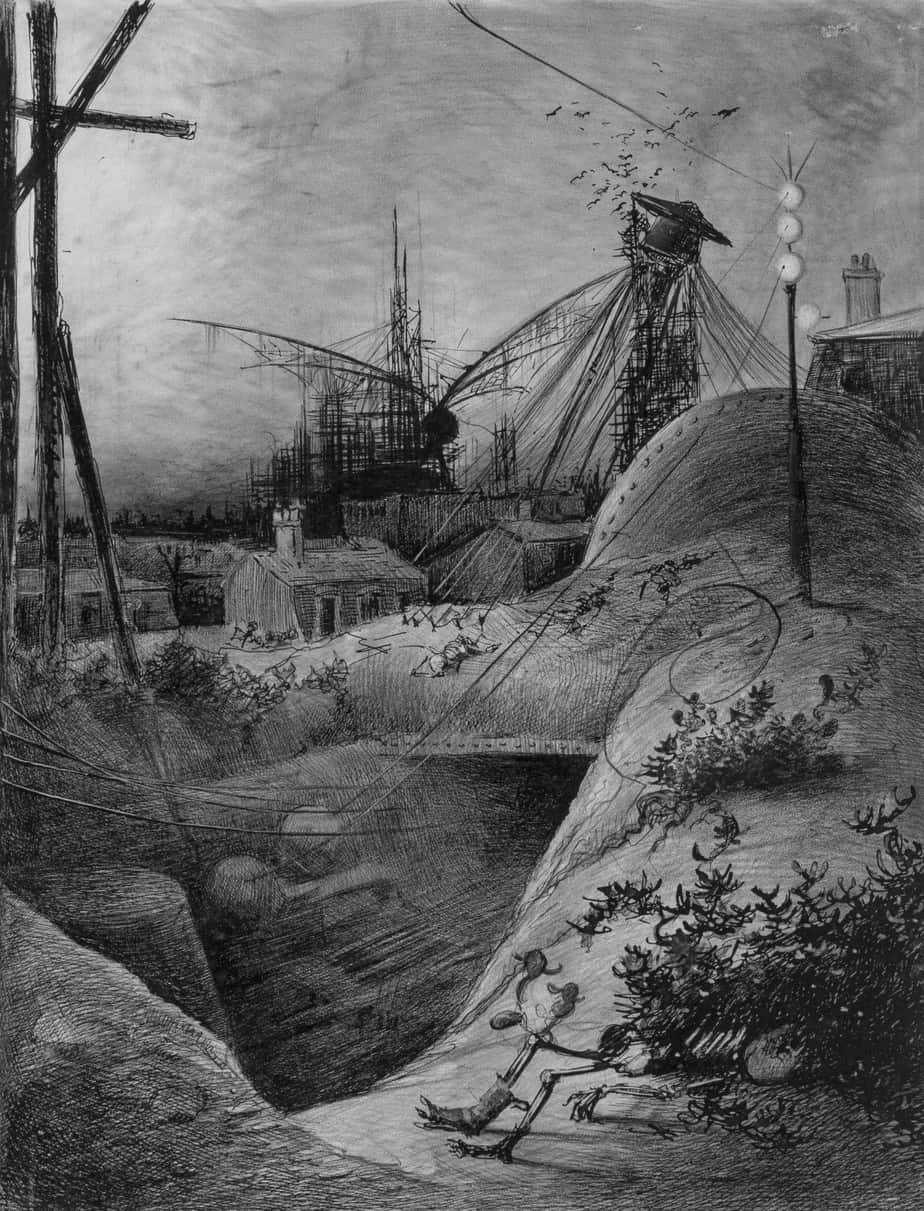

The Slenderman creature reminds me of artwork for War of the Worlds by Henrique Alvim Corrêa.

What Is The Definition Of An Urban Legend?

Urban legends are contemporary, orally transmitted tales that “often depict a clash between modern conditions and some aspect of a traditional life-style (Brunvard, 1981).

Urban legends, in general, are best understood as unconstructed social problems, meaning, the story is about one thing (fictitious) but speaks to another thing (a real social problem). Urban legends which feature harmed to children proliferated in the 1960s and 70s, when the public became increasingly engaged with campaigns promoted by physicians and social workers: Child abuse is a major social problem. Children are not safe. Childhood is not an idyllic time for many.

Even parents who were able to bring their children up in safe homes now became worried about the scourge of drugs. Anyone at all could now lose their teenager to the scourge of drugs, or to radical political activism so different from their own worldview.

Many urban legends feature crime. The American public’s fear of crime rose significantly during the 1960s and 70s. Most violent crime features a perpetrator and victim who are acquainted, urban legends focus on stranger danger.

‘Urban legends are a product of social strain, and of the social organization of the response to that strain’ (Best and Horiuchi).

In general, urban legends are a product of false threat.

The difference between urban legends and traditional legends

Basically, urban legends are modern folk tales. They fit neatly into a classification of “Horror Story” (Z500-599 in Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966).

Horror stories. These are stories which are not ghost or witch stories — they usually do not deal with the supernatural — which are told because of the effect of horror they produce in the listener. Usually the emphasis is on the grisly or strange rather than on the supernatural.

the final page of Baughman’s 1966 book

The term ‘urban legend’ is generally used by folklorists to distinguish modern folk tales from those told in traditional societies.

Traditional legends frequently feature supernatural themes. Most urban legends ‘are grounded in human baseness’, according to Fine, 1980.

- criminal attacks

- contaminated consumer goods

- various risks of urban life

Like any fairy- or folk tale, these oral stories change and evolve as they spread from person to person, group to group. Urban legends adapt well to a wide variety of media: film, TV, books, games, and occasional sensationalist filler for newspaper and online media.

Sometimes, a real event becomes urban legend which then becomes film.

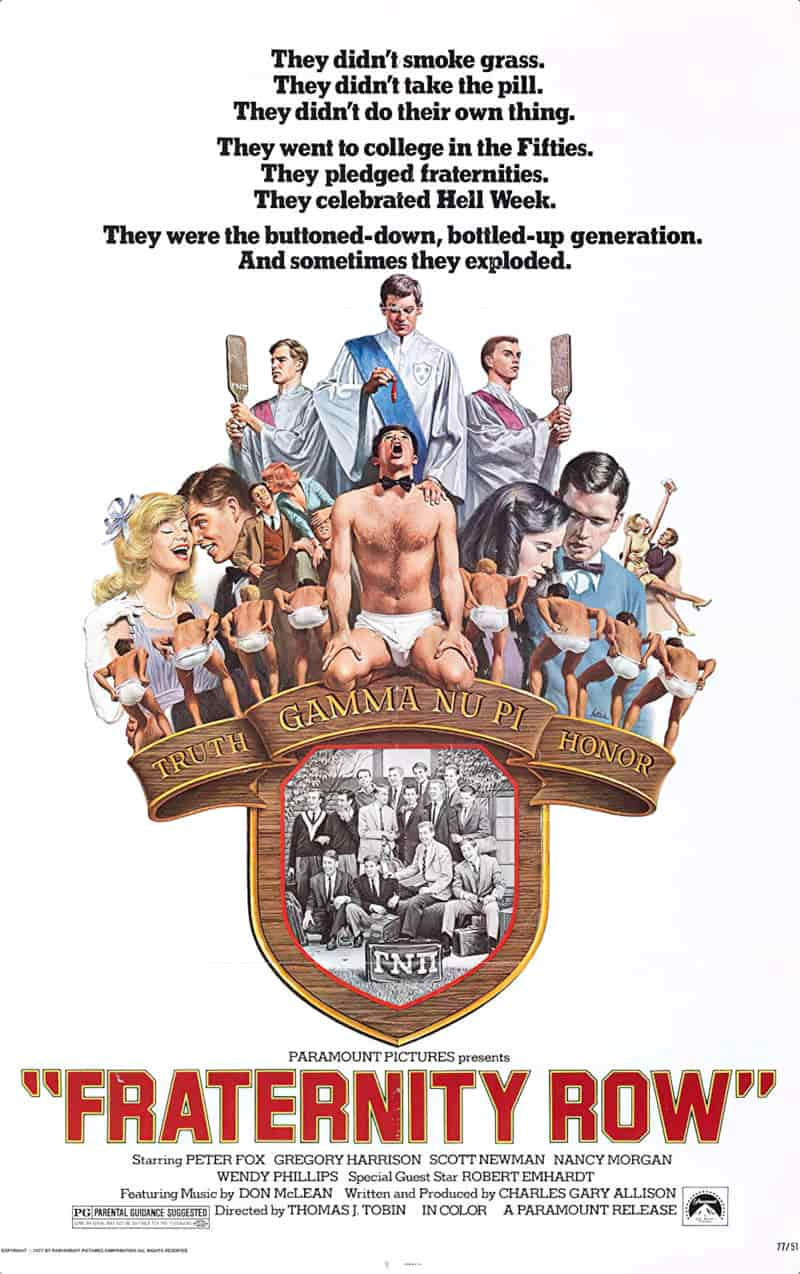

FRATERNITY ROW (1971)

Private film production about an upper class college in the early ’50s and how a “harmless” hazing resulted in a student’s death.

Stories about a fatal fraternity initiation can be found in urban legend (e.g. the one where headlight flashers are chased down and murdered).

This film makes use of the tropes. Apparently the story is based on the writer-producer’s own experience. (Charles Gary Allison)

See: Her Son’s Pointless Death Spurs An Angry Mother’s War Against Fraternity Hazing in the archives of People magazine.

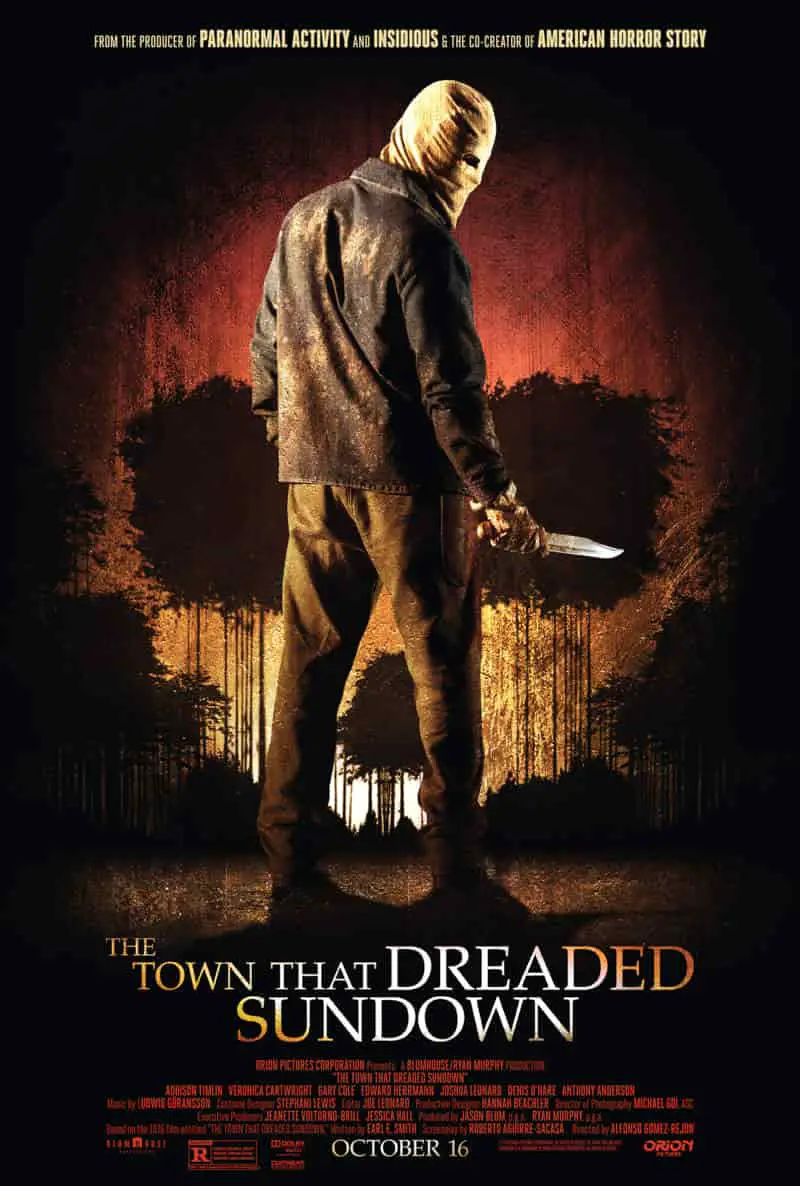

THE TOWN THAT DREADED SUNDOWN (1977)

Billed as a true story.

“In 1946, this man killed five people! Today he still lurks in the streets.”

A mysterious killer lurks in a Texarkana lovers’ lane in 1946. The story shares many similarities to the Hook urban legend.

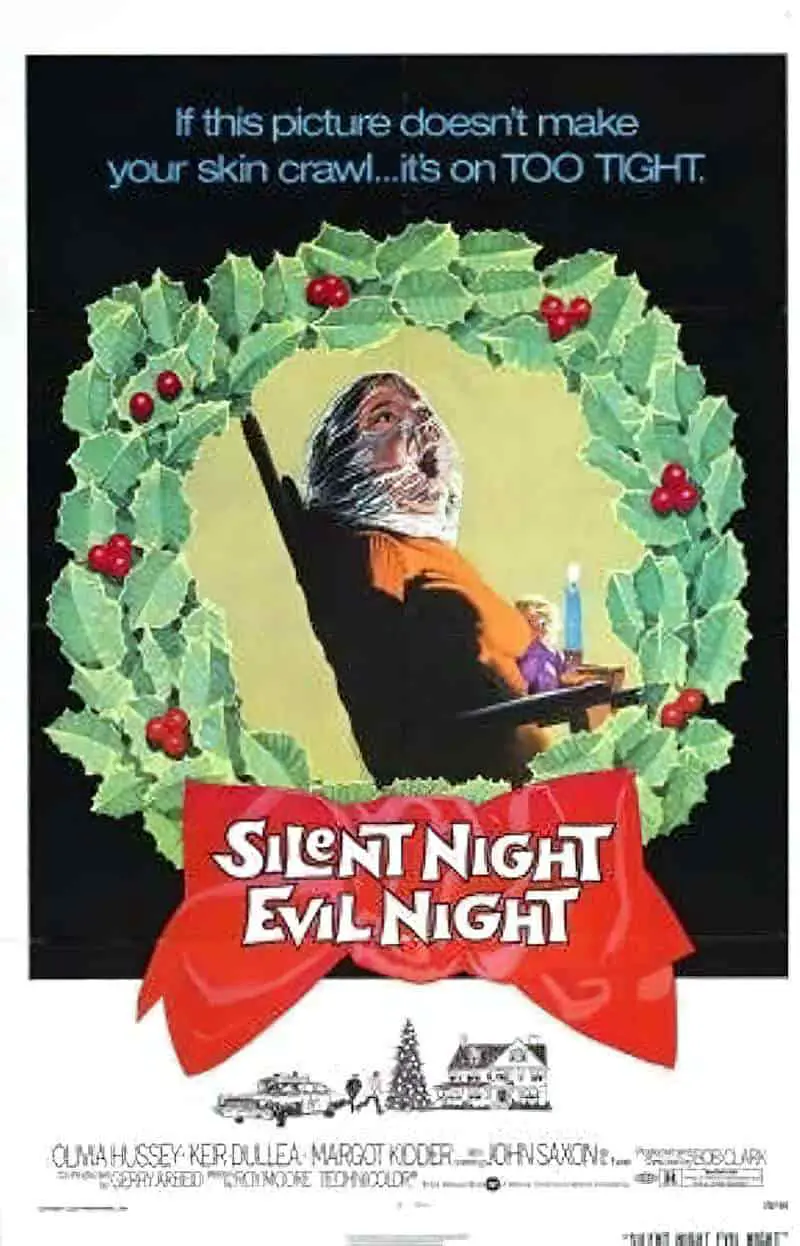

SILENT NIGHT, EVIL NIGHT (1974)

Also released under the titles: Stranger in the House and Black Christmas. The titles were changed before release was unsuccessful.

In the story, it is Christmas time. Sorority house residents are frightened by obscene phone calls followed by a systematic attack on individual women in the residence. This film was due to be broadcast by the NBC in early 1978.

But one week before airing, Ted Bundy murdered two women and beat three others after breaking into a Florida State University sorority house. (He was arrested the following month after a police officer thought his car looked suspicious.)

The NBC decided not to show the film out of respect for the victims and their families. However, Ted Bundy remains a figure considered ripe for entertainment cf. Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile (2019). (More on this film at VHS Revival: A retro movie magazine.)

The stories change to fit whatever fear proliferates at the time. Focusing on urban legends about contaminated food:

- Fairy tales such as “Snow White” speak to fears about accepting contaminated food from strangers. A literary fairy tale such as “The Juniper Tree” speaks to the masculine fear of mistrusting a housewife who is totally in charge of the family food preparation.

- But if men couldn’t trust their own wives, nor could anyone trust outside cooks and chefs. The dangers of eating commercially prepared food have been around since the 1800s, in stories about baked pies made with cat meat.

- The urban legend of the deep-fried rat speaks to the very specific fear around the practice of deep frying: You can’t see what’s underneath, and must trust when biting into the product that the food is as advertised.

- Halloween contamination of trick-or-treat goodies took off in the early 1970s and is probably a reaction to the new popular view that American childhood is a dangerous time. (Drugs, the Vietnam War killing off many young men, increased popular knowledge of child abuse which was previously invisible and ignored.)

[R]ecognition by a society of its social problems is a highly selective process, with many harmful social conditions and arrangements not even making a bid for attention and with others falling by the wayside in what is frequently a fierce competitive social struggle.

Blumer, 1971

While urban legends are a product of false threat, the political construction of social problems deals with genuine threat.

Occasionally, urban legends appear in newspaper stories. This reinforced the tale’s credibility.

- From the start of the 1970s, the American public was warned to be vigilant against Halloween sadlsts tampering with candy. The two 1980s deaths which had occurred (a five-year-old and, separately, an eight-year-old boy) had actually been caused by male family members, not by candy contaminated by a stranger while out trick-or-treating.

- Much more recently, we have the transphobic urban legend in which a teacher was (supposedly) required to provide kitty litter for a student who identified as a cat. The factual portion of this story is far more disturbing: Teachers were stocking up with supplies in preparation for active shooters. The kitty litter was to accommodate for the reality that in a hostage situation, children would be unable to use the toilet, hence kitty litter in a large bucket.

Why do urban legends propagate?

Why do these narratives gain so much traction, and why are we so keen to believe them?

Beth Singler at the University of Zurich in Switzerland says that the media has an obvious incentive to publish such claims: “fear breeds clicks and shares”. But she says that humans also have an innate desire to tell and hear scary stories.

Reports of an AI drone that ‘killed’ its operator are pure fiction, New Scientist

Why do urban legends endure?

PSYCHOLOGICAL REASON FOR URBAN LEGEND

Psychologically, urban legends are a way for us to make sense of the world and manage threat in a safe environment. From the perspective of believers, myths act as proof and reinforce existing beliefs. This is important because they help to validate an person’s worldview and in doing so legitimatises their fears as real and genuine.

The Conversation

Broadly, urban legends deal with the fear of contact with strangers. Until the modern era, people knew almost everyone they encountered on a daily basis. Daily contact with strangers is a new phenomenon. We no longer know who to trust. Certain stories exist to preserve a social order in which we receive reassurance that bad actors will be punished accordingly.

Urban legends are inherently conservative. We are motivated to believe information which confirms our existing views and opinions:

- “The Hook” — young adults shouldn’t be fooling around having sex before marriage

- “Deep-fried Rat” — food which hasn’t been prepared by women in the home can’t be trusted

- “The Choking Doberman” — don’t rob people’s houses

- “Beehive Spider” — new fashions (especially female fashions) are ridiculous and can kill you

- “Bloody Mary” — some women are witches and women can kill you, even from beyond the grave

- “The Vanishing Hitch-hiker” — taking the back road is dangerous, especially if you pick up hitch-hikers

- “Gang Initiation” — mind your own business on the road, attracting as little attention as possible to your vehicle to avoid road rage

- “Slender Man” — children should keep out of the woods (actually an ancient warning, seen in “Little Red Riding Hood“, “Hansel and Gretel” etc. These days, ‘the woods’ stands for any isolated spot beyond the safety of well-populated civilisation.

Urban legends use fear to promote conservative ideas and ideals

Unless subverted by less conservative storytellers, urban legends rely on misogyny, ableism, ageism, transphobia and all the other -isms and -phobias of the day. These stories serve to both reflect and reinforce existing stereotypes and biases.

URBAN LEGENDS HAVE ENTERTAINMENT VALUE

Urban legends exhibit features common to successful narrative:

- A generic main character — Anyone is supposed to identify with them. (The Every Man, the Every Woman, the Every Girl…)

- Sometimes this generic main character is an archetype who deserves punishment according to conservative societal values (oftentimes it’s a sexually alluring teenage girl — a girlfriend, a babysitter…) These stories appeal to a conservative sense of retribution. (“She shouldn’t have been necking in lover’s lane if she didn’t want to get murdered…”)

- A formidable opponent — These opponents rely on a culturally shared notion of sadlsts, narcissists and psychopaths (regardless of whether the depiction is the slightest bit recognisable in the field of psychology). These are “Minotaur Opponents” with no humanity, much like a tsunami or cyclone.

- Resonant detail (usually because it’s horrific)

- Defamiliarised settings — strange but familiar homes, suburbs, brand names, fast-food outlets. We recognise these settings — these stories could easily happen to us, or to our own family and friends.

- A Snail Under The Leaf — things look fine on the surface, but dig just a little deeper and something terrible lurks

SOCIAL COHESION

Sharing an urban legend can be a form of gossip. Some people share stories to foster social relations, regardless of whether their stories are true. It can feel good to share a good narrative under the guise of providing useful information to those you supposedly care about.

FURTHER READING

The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences

We tend to think of ourselves—our modern selves–as disenchanted. We have traded magic, myth, and spirits for science, reason, and logic. But this is false. Jason Josephson-Storm, in his exciting new book titled The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences (University of Chicago Press, 2017) challenges this classical story of modernity. Josephson-Storm, associate professor in and chair of the Department of Religion at Williams College, argues that modernity is riddled with magic, and that attempts to curtail it have often failed. Adding a twist to a well-known expression, he writes that we have never been disenchanted. Josephson-Storm investigates the human sciences—philosophy, psychoanalysis, sociology, and folklore studies, to name a few—which were critical to the creation and spread of the myth of a mythless society. But the human sciences were themselves also deeply entangled with magic. They often, Josephson-Storm reveals, emerged from occult origins, flirted with the paranormal, or even produced new enchantments. As can be surmised from this brief description, the audience of The Myth of Disenchantment will be a broad and eclectic one. The book will be of interest to scholars in religious studies, science and technology studies, and historians of philosophy, science, ideas, culture, and Europe.

New Books Network

CHILD ABDUCTION

Unfortunately, some terrible things sound like urban legends but at at least one point in history were true. Writing of disabled children in Nazi Germany, Joanne Limburg explains:

Condemned children were taken away in buses with darkened windows; a few weeks later, their parents would be sent letters informing them of their child’s death, with cause and date altered. Many children were given lethal doses of medication, by tablet or injection, delivering a death which was usually neither quick nor painless; others were slowly starved to death. Despite the official lies, people understood what was happening. Local children knew enough to frighten each other with threats of buses.

Letters To My Weird Sisters, Joanne Limberg, 2023

REFERENCES

- THE RAZOR BLADE IN THE APPLE: THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF URBAN LEGENDS BY JOEL BEST AND GERALD T. HORIUCHI, CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY Social Problems, Vol. 32, No. 5 (Jun., 1985), pp. 488-499

- “Social problems as collective behavior.” Social Problems, 1971 by Herbert Blumer

- The Vanishing Hitchhiker, 1981, New York: Norton by Jan Harold Brunvand

- The Choking Doberman, 1984, New York: Norton by Jan Harold Brunvand