When you were a kid, did your caregiver have a ‘go to salve’ for a wide variety of uses? The Australian side of my family grew up with a product called Lucas’ Pawpaw Ointment, which comes in a distinctive red tubes and tubs.

That red colour? That’s nothing compared to the smell. Actually, if a smell had a colour, that’d be it. You can buy this stuff in any Australian supermarket or pharmacy.

In his 1906 handbook, after years of research, botanist and surgeon T.P. Lucas stated that he believed the papaw was the finest natural medicine yet discovered.

from the Lucas’ Pawpaw website

For me, growing up in Aotearoa New Zealand, it was Rawleigh’s Ready Relief, a small glass bottle of strongly aromatic liquid which you’d sprinkle onto a folded hanky and keep in your pocket for periodic sniffing purposes. The stuff was strong; it really would clear your sinuses. When lining up at school, someone would inevitably exclaim, “Pooh, who stinks?” (In which case you’d be well-advised to keep quiet. No one will ever discover the burning stink comes from you, and that you were sent to school to spread a virus despite being blocked up with a 1980s version of corona because — so long as you have a smelly hanky in your pocket — you’ll be right as rain!)

Rawleigh’s doesn’t have a shop front, only independent distributors. In New Zealand you find vendors at stalls of flea markets, regional fairs and so on, which makes the product seem a little witchy. If you see one of these semi-retired guys you buy the stuff when you can. These guys are known as ‘Rawleigh Men’, like the masculinised version of The Avon Lady. They used to sell door-to-door.

Turns out Rawleighs have a website now, but the mystical, Victorian era connotations around Rawleigh’s Ready Relief hasn’t entirely gone away.

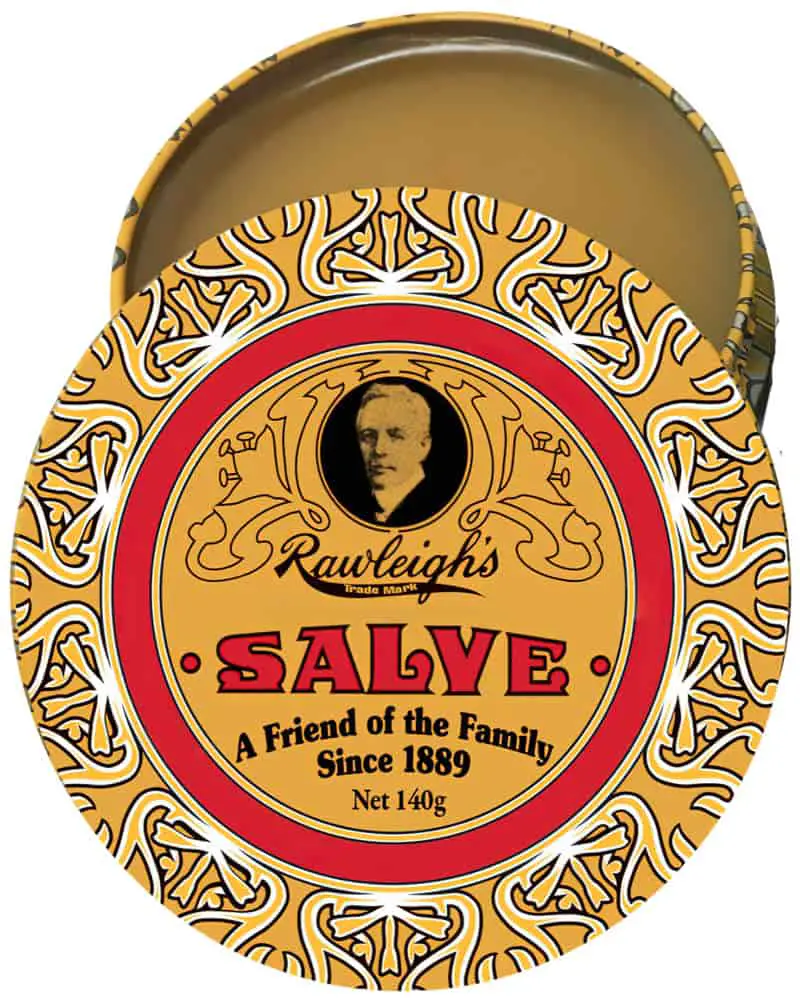

The Rawleigh’s Company have expanded their product line and now they make a variety of ointments. The salve in the yellow tin is an old product and absolutely stinks. If it works as well as it stinks, it’s a cracker of a product. If that was ever open as a kid I knew the wound was serious. I can’t even describe the pong, except to say it goes hand-in-hand with the stink of fabric bandages secured with tiny safety pins. If you know your pongs, the ingredient list may explain it:

- Colophony (what the hell is this, i bet this is the culprit)

- Cresol

- Paraffin

- Gum resin

In contrast, the salve in the blue tin smells very pleasant, like a milder version of the American Vicks Vaporub, with a slightly different balance of the same ingredients.

Knowing jack about candles, the ingredients list of blue-tin Rawleighs reads to me like the equipment list for a candle-making night class:

- Camphor

- Eucalyptus oil

- Menthol

- Lanolin

- Paraffin wax

- Ceresin wax

Rawleigh’s ‘Friend-in-a-can’ has been ‘in the family’ since 1899, a few years before an American pharmacist by the name of Lunsford Richardson, thousands of miles across the ocean, put together another nice-smelling salve, hoping to soothe his own baby’s cough. Seemed to do the trick. He then started selling it.

Wouldn’t it be nice to know if Lunsford Richardson stole the idea off Rawleighs or if he happened to come up with it entirely on his own, just a few years after Rawleighs hit the market? William Rawleigh was only a teenager when he went door-to-door selling his smelly liniment:

Rawleigh’s life as an independent salesman began on April 6, 1889, when he was 18 years old. Initially he turned his mother’s kitchen into a part-time factory in order to produce liniment, until he could get enough money together to rent a small building. Many medicines were made, bottled and labelled in the Rawleigh family home. […] Rawleigh’s expansion continued after the war with factories established in Melbourne, Australia, in 1928 and in Wellington, New Zealand, in 1931. He also established warehouses in Zanzibar, Madagascar and Sumatra, where raw materials such as vanilla, cloves, pepper, ylang-ylang and oil of geranium were assembled before being shipped to his factories.

Wikipedia

With a magnificent name like Lunsford Richardson, the inventor of Vicks had trouble fitting his own name onto the side of a small jar, so he decided to go with his brother-in-law’s name instead. Vicks Family Remedies.

Every cloud a silver lining: When the Spanish Flu broke out (nothing to do with Spain) jars of Vicks flew off the shelves in great quantities. Lunsford Richardson would have become a very wealthy pharmacist, had he not himself died of Spanish flu.

After Richardson’s death, and after the flu deaths settled down, the company who purchased the sweet-smelling salve noticed that sales fell significantly in summer. So they started a crafty marketing campaign. This was before accountability laws in advertising existed, so they could basically claim what they liked. They told the gullible public that Vicks was good for bee-stings, scratches, bug bites, poison-ivy and… (does this sound suspiciously like they were targeting summertime afflictions?)

Fast forward to 1985. Vicks, now called Vicks Vaporub, is owned by Proctor & Gamble, who are very keen to avoid litigation. If you go to their website they will tell you to use their product only as directed. If you call their helpline, an entire line is dedicated to myth-busting. No, you can’t use Vicks Vaporub as superglue. No, you can’t put it in your engine. (Actually no. They’ll tell you it doesn’t treat fungus.)

Because many consumers still think that Vicks can be used for many, many things.

The Experiment podcast from WNYC Studios has an episode called “Just Put Some Vicks On It“. The presenter talks to her elderly grandmother who emigrated to American from Cuba at around the age of 30, and has such a close relationship with Vicks she lovingly calls the product “Vickicito”, and has used it, variously, for:

- toenail fungus

- strengthening fingernails

- hair conditioner

- hand and foot lotion

The presenter suggests the proliferation and multiple uses of Vicks may be connected to the civil strife her grandmother experienced as a young adult, and the fact that Vicks, along with other American products, was provided in large quantities to troops during the Bay of Pigs Invasion.

In their memoir, Australian comedian Hannah Gadsby uses her mother’s all-purpose use of Vicks Vaporub as a running gag, starting with a childhood incident in which she was quite badly injured:

Mum has always liked to indulge in contrary diagnosis, and if Mr Bannon had arrived on our front porch supporting my right hand in his, proclaiming that I’d broken my arm, then Mum would likely have countered with the diagnosis of ‘sprain’ or ‘nothing at all’. She might’ve rubbed some Vicks Vaporub onto the ‘supposed’ injury before sending me outside to pick the carrots for dinner. Luckily for me, Mr Bannon insisted it was a sprain, so Mum decided it was far more serious. ‘What the hell would he know?” she said as she closed the door in his face.

Hannah Gadsby, Ten Steps to Nanette

In the opening to her 1970 novel The Bluest Eye, Toni Morrison describes the harshness of getting sick as a child, and shows readers the (non-recommended) practice of forcing a child to take Vicks salve orally:

Our house is old, cold, and green. At night a kerosene lamp lights one large room. The others are braced in darkness, peopled by roaches and mice. Adults do not talk to us — they give us directions. They issue orders without providing information. When we trip and fall down they glance at us; if we cut or bruise ourselves, they ask us are we crazy. When we catch colds, they shake their heads in disgust at our lack of consideration. How, they ask us, do you expect anybody to get anything done if you all are sick? We cannot answer them. Our illness is treated with contempt, foul Black Draught, and castor oil that blunts our minds.

When, on a day after a trip to collect coal, I cough once, loudly, through bronchial tubes already packed tight with phlegm, my mother frowns. “Great Jesus. Get on in that bed. How many times do I have to tell you to wear something on your head? You must be the biggest fool in this town. Frieda? Get some rags and stuff that window.”

Frieda restuffs the window. I trudge off to bed, full of guilt and self-pity. I lie down in my underwear, the metal in the black garters hurts my legs, but I do not take them off, because it is too cold to lie stockingless. It takes a long time for my body to heat its place in the bed. Once I have generated a silhouette of warmth, I dare not move, for there is a cold place one-half inch in any direction. No one speaks to me or asks how I feel. In an hour or two my mother comes. Her hands are large and rough, and when she rubs the Vicks salve on my chest, I am rigid with pain. She takes two fingers’ full of it at a time, and massages my chest until I am faint. Just when I think I will tip over into a scream, she scoops out a little of the salve on her forefinger and puts it in my mouth, telling me to swallow. A hot flannel is wrapped about my neck and chest. I am covered up with heavy quilts and ordered to sweat, which I do, promptly.

Later I throw up, and my mother says, “What did you puke on the bed clothes for? Don’t you have sense enough to hold your head out the bed? Now, look what you did. You think I got time for nothing but washing up your puke?”

The puke swaddles down the pillow onto the sheet — green-gray, with flecks of orange. It moves like the insides of an uncooked egg. Stubbornly clinging to its own mass, refusing to break up and be removed. How, I wonder, can it be so neat and nasty at the same time?

My mother’s voice drones on. She is not talking to me. She is talking to the puke, but she is calling it my name: Claudia. She wipes it up as best she can and puts a scratchy towel over the large wet place. I lie down again. The rags have fallen from the window crack, and the air is cold. I dare not call her back and am reluctant to leave my warmth. My mother’s anger humiliates me; her words chafe my cheeks, and I am crying. I do not know that she is not angry at me, but at my sickness. I believe she despises my weakness for letting the sickness “take holt.” By and by I will not get sick; I will refuse to. But for now I am crying. I know I am making more snot, but I can’t stop.

My sister comes in. Her eyes are full of sorrow. She sings to me: “When the deep purple falls over sleepy garden walls, someone thinks of me. . . .” I doze, thinking of plums, walls, and “someone.”

But was it really like that? As painful as I remember? Only mildly. Or rather, it was a productive and fructifying pain. Love, thick and dark as Alaga syrup, eased up into that cracked window. I could smell it — taste it — sweet, musty, with an edge of wintergreen in its base — everywhere in that house. It stuck, along with my tongue, to the frosted windowpanes. It coated my chest, along with the salve, and when the flannel came undone in my sleep, the clear, sharp curves of air outlined its presence on my throat. And in the night, when my coughing was dry and tough, feet padded into the room, hands repinned the flannel, readjusted the quilt, and rested a moment on my forehead. So when I think of autumn, I think of somebody with hands who does not want me to die.

from the opening to The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

In “Images” by Alice Munro (1968), a young narrator remembers a formidable older family member, not least for her smell:

Outdoors, in the cold March air, she lost some of her bulk and her smell. In the house I could always smell her, even in the rooms she seldom entered. What was her smell like? It was like metal and like some dark spice (cloves—she did suffer from toothache) and like the preparation rubbed on my chest when I had a cold. I mentioned it once to my mother, who said, “Don’t be silly, I don’t smell anything,” So I never told about the taste, and there was a taste too. It was all the food Mary McQuade prepared and perhaps in all food eaten in her presence…

“Images” by Alice Munro

MY WORKING THEORY ABOUT CURE-ALL SALVES

To become a ‘friend of the family’, a product must:

- Have been invented ages ago, preferably at the end of the 19th century

- Have a very distinctive smell (explains why the distinctive smelling WD-40 is also prone to Internet listicles regarding the manifold household purposes of lubricant in a can)

- Related to the previous condition: Must evoke strong memories from childhood

- Human brains love the idea of single products with many uses

It helps if the company itself promoted cure-all qualities before advertising standards kicked in. (Here’s looking at you, Vicks.)

But clearly, these salves should not be taken orally. They should not be inserted into the ear canal. (Nothing should be.) They do not contain antihistamines, so do nothing to soothe bee stings. Why, then, do people continue to believe that there’s a jar of goop in the cupboard which works for many purposes? Some of these products have garnered so much lore around them, their multipurpose status has achieved the status of Full Urban Legend.

The age of the Internet works both ways: Correct product information is available within seconds, but so is disingenuous information, written by people who are literally just making things up. And now we have ChatGPT.

I asked ChatGPT to “Give me 50 uses for vicks vaporub.” The disclaimer at the bottom hardly cancels out the fact that it has collected from its database many, many bad and harmful uses which have been suggested over the years:

ChatGPT, accessed 12 April 2023

- Relieving cold and flu symptoms

- Soothing sore muscles

- Treating sinusitis

- Alleviating coughs

- Easing headaches

- Reducing fever

- Reducing nasal congestion

- Relieving asthma symptoms

- Relieving bronchitis symptoms

- Treating ear infections

- Alleviating mosquito bites

- Relieving sunburn pain

- Treating athlete’s foot

- Treating toenail fungus

- Reducing the appearance of bruises

- Relieving menstrual cramps

- Treating hemorrhoids

- Soothing insect bites

- Treating eczema

- Relieving muscle aches

- Treating cracked heels

- Treating dry skin

- Reducing dandruff

- Relieving joint pain

- Soothing a sore throat

- Treating tennis elbow

- Treating osteoarthritis

- Relieving tension headaches

- Treating dry, cracked lips

- Reducing the appearance of scars

- Treating cuts and scrapes

- Treating burns

- Treating chapped skin

- Soothing a stuffy nose

- Relieving insect stings

- Treating plantar fasciitis

- Treating diaper rash

- Treating cold sores

- Treating canker sores

- Treating warts

- Treating psoriasis

- Treating acne

- Treating skin rashes

- Relieving muscle spasms

- Treating hives

- Soothing the symptoms of arthritis

- Treating chilblains

- Reducing the appearance of stretch marks

- Treating poison ivy and poison oak rashes

- Relieving minor aches and pains.

THE PSYCHOLOGY BEHIND MULTIPURPOSE PRODUCTS

Let’s turn away from the bathroom cabinet and take a wander into the shed, where we will likely find a hammer.

Kaplan’s Law of the Instrument

Kaplan’s Law is a cognitive bias: With limited tools, single-minded people apply them inappropriately or indiscriminately.

Give a small boy a hammer, and he will find that everything he encounters needs pounding.

Abraham Kaplan

What is that other, similar saying about the man with the hammer? That comes from another guy who also happens to be called Abraham. This time it’s Abraham Maslow (yep, the hierarchy of needs guy).

To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

Abraham Maslow

To a neighbour a with a leaf blower… To a kid with a glue gun… To an unhinged President with access to the nuclear code… The list goes on and on.

tbh if someone just handed me a pressure washer and set me loose in the streets i would go into a trance and just start hosing shlt down indiscriminately. it’s not a question of how much i could clean, but how long until i get hit by a car and die

brainscrewz on Tumblr

(Someone else points out that there’s a game to satisfy this need. It’s called Power Washer Simulator.)

Maslow’s observation is often shortened to ‘Maslow’s Hammer’. Not that it matters now, but credit where credit’s due: Maslow actually said the hammer quote two years after Kaplan did, and even then, the idea wasn’t original. An English expression ‘Birmingham screwdriver’ refers to a hammer which can be used for everything, and is at least 100 years earlier than either of the Abrahams.

We love products which ostensibly accomplish many different tasks. This no doubt appeals to our individualistic desire to survive alone in the wild if we had to.

MAGICAL MULTIPURPOSE PRODUCTS IN STORYTELLING

Which stories cater to our collective desire for a product which either fills many needs, or the single need of many people?

- The king of this genre: Magic lamps or boxes, which contain a genie who grants you wishes.

- Magic Porridge Pot fairytales, in which a container keeps filling and re-filling. This story also contains a warning: If you expect one thing to solve all your problems, it won’t go well. Your monotropism will get away on you.

- As a short story example, I recommend “Miracle Polish” by Steven Millhauser, whose house ends up filled with mirrors. Like cure-all salves, cleaning products are also prone to the ‘clean everything with this single product’ thinking. This is probably more true than we think. What’s the difference between kitchen cleaner and bathroom cleaner? Different packaging. Perhaps one is slightly better with soap scum, the other a little better with grease. But many people swear that you can clean anything in a household with baking soda and vinegar.

- In Alice Munro’s short story “Western Brothers Cowboy“, the young narrator’s father takes on the low-status job of a travelling salesman during The Great Depression. This economic depression happened to coincide with the flu epidemic, when many people could not afford to see a doctor. Alice Munro lists all the things the father sells, including a number of products which were no doubt considered cure-alls.