“Up At A Villa” is a short story by Helen Simpson, opening her 2011 collection In-flight Entertainment. This is a lyrical short story full of symbolism.

Cover copy tells us to expect work a la Alice Munro. Of all the stories here, the images in “Up At A Villa” are most reminiscent of Munro — young and old are juxtaposed, reminding the reader that we are all young and old at some point, and therefore young and old at once.

As for the style and storytelling techniques, this story is far more similar to the work of Katherine Mansfield than to Alice Munro.

We are meant to believe it’s possible to get rich and save our oceans, save our environment at the same time, but no one can say exactly how.

Polly Hemming, Director at The Australia Institute’s Climate & Energy Program.

CHARACTERS OF “UP AT A VILLA”

This is a story of two groups of people. The first group comprises two heterosexual pairs of young people in their late teens or early twenties. The characters named Nick and Tina are romantic and flirtatious with each other. The other pair, Joe and Charlotte, do not feel that way about each other, or Charlotte does not feel that way about Joe. Helen Simpson paints this picture in extremely succinct fashion and we know it by the end of the third paragraph, observing these young people waking up from the forest after a drunken night of frolicking. We know this about them from the way they behave around the pool and in the water. We’d know it if we were seated nearby. And that’s where Simpson puts the reader. We’ve been given an invisible pool-side seat.

These two young couples juxtapose against another couple — older. This older couple has a new baby. This could of course be either of the young couples in another ten years’ time.

SETTING OF “UP AT A VILLA”

There’s a fairytale vibe to this short story, which is probably set in Southern France. Local food provides this detail —pissaladière — cuisine of Nice. It’s Monday morning and everything is closed down in the village (fermé le lundi). The young couples have snuck onto this holiday villa to use the pool as they’ve run out of money, which reminds me of the opening of Brokedown Palace, the 1999 film about two young American women who eventually find themselves imprisoned for drug trafficking.

It’s mid afternoon and these kids have their morning sleeping in the forest, redolent with fairytale spookiness. Their hair is ‘stuck with pine needles’. They’ve become one with the forest, but could the story be making use of the double English meaning of ‘pine’, much as Robin Black did in her short story “Pine“?

In stories the forest can function as all kinds of things, most notably the subconscious. When they wake up in the forest, have they really woken up? What follows around the pool could easily be part of a dreamscape.

Helen Simpson inverts the general utopian beachspace of our imaginations by describing the Mediterranean this way:

Anyway they had fallen out of love over the last week with the warm soup of the Mediterranean, its filmy surface bobbing with polystyrene shards and other unsavoury orts.

‘Ort’ is an archaic word, linking this contemporary setting to an archaic world and means ‘a scrap or remainder of food from a meal’. Alongside breastmilk, this word choice links something which shouldn’t be eaten with food. (Of course breastmilk is food — the best human food that exists — but that’s not how the young observers see it.)

Three bodies of water are mentioned in this story: first the sea, then the pool, then the baby’s bath when Harvey asks the woman what’s so special about bath-time anyway? This creates a very subtle mise-en-abyme effect, from large down to small — the grievances are likewise becoming more petty, while at the same time carrying the magnitude of a sea for this couple.

‘Space’ and ‘Place’ are not the same thing. Drawing on spatial theory by Lawrence Buell and E. V. Walter, a place is seen, heard, smelled, imagined, loved, hated, feared, revered, enjoyed, or avoided. In contrast, the Space is the subjective dimension of located experience. Because certain Spaces exist in the shared cultural imagination, it’s possible to be familiar with a ‘space’ without having visited a ‘place’. For instance, if you live in Australia or have seen tourist advertising, you’ll be familiar with beachspace even if you haven’t ever visited (the place of) an actual beach. Likewise, we are all familiar with images of the Mediterranean even if we haven’t visited the Mediterranean:

In other words, we know a Space of even if we don’t know the Place. This applies to the tourists in Helen Simpson’s story, whose knowledge of the Space has been replaced by unwelcome knowledge of the Place. Evoking the story of Adam and Eve — these kids were happier before they saw the polystyrene. Now their imaginative Space will be forever tainted.

What about the symbolism of the pool? In a few deft strokes, Simpson evokes a scene of ancient mythology — modernised, of course — but this pool could easily be a lake or a pond in a forest. The naked young people, the youthful bodies… well, they could be sirens, of course.

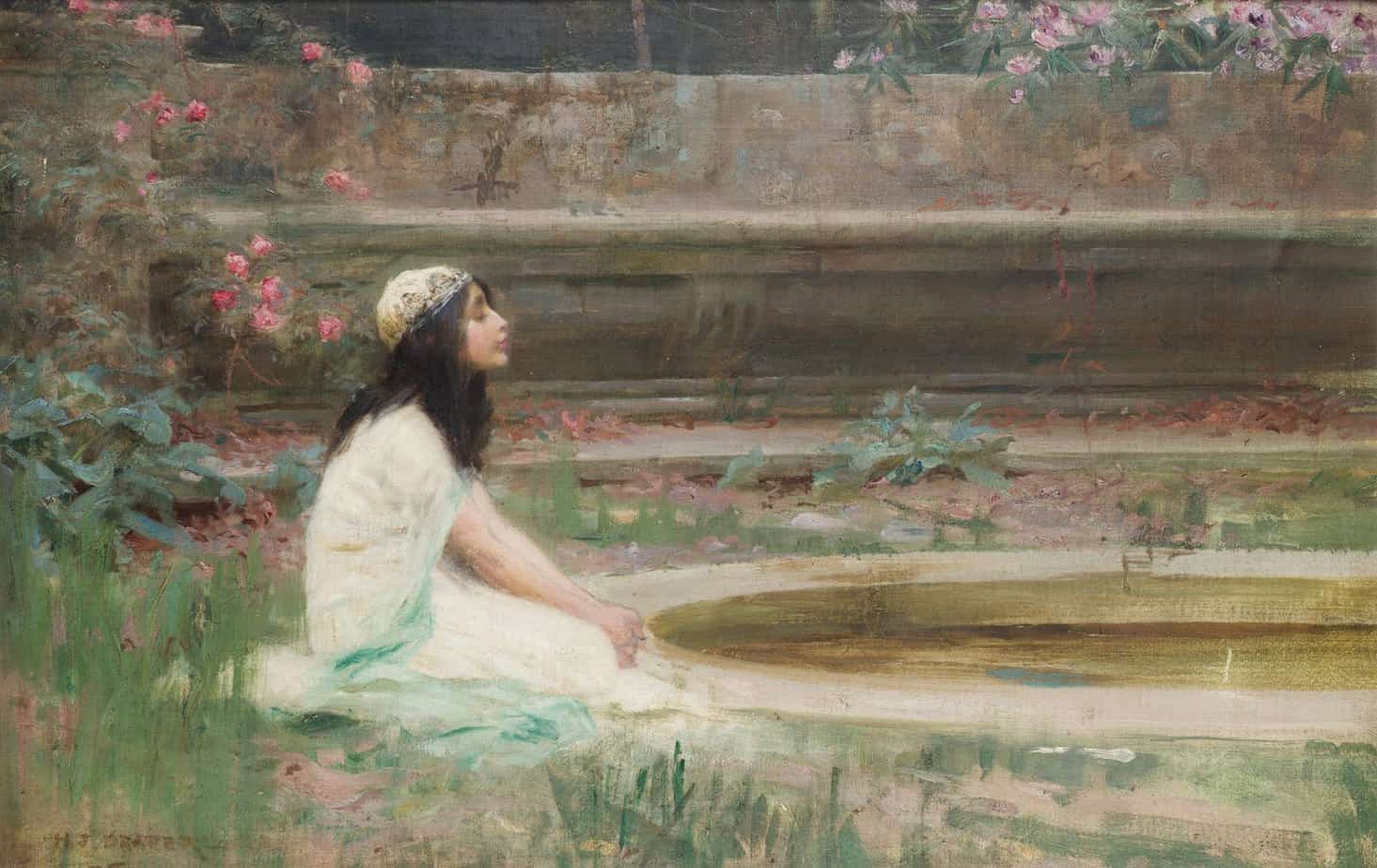

What do you imagine when you think ‘siren’? Probably of beautiful femme fatales fresh out of Romanticism…

… or perhaps something more like this…

… not the sirens of Ancient Greece, where winged and clawed bird-women lured sailors to destruction through the power of their song.

Sirens Are Actually Bird-Bodied Messengers of Death, Not Sexy Mermaids.

Audiences didn’t exactly appreciate John William Waterhouse harking back to the earlier era of sirens. I mean, these women are terrifying. And no one wants to go to an art gallery and look at terrifying women, do they? Women are supposed to be warm and sexy and alluring and welcoming.

[A woman’s] value [is] contingent on her giving moral goods to them: life, love, pleasure, nurture, sustenance, and comfort, being some

Kate Manne, Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny

The same thing has happened to witches, female vampires and basically any femme/androgynous mythical creature (including gothic male vampires). We love to sexualise anyone who’s not overtly manly.

Anyway, this story is perhaps Helen Simpson’s reclamation. Because of the varied history of siren mythology, these hybrid creatures are useful to storytellers when weaving an imagistic pattern. (Double-duty symbols always are.)

Though Simpson has left the siren mythology off the page, I think it’s there in her imagery. An important thing to understand about metaphorical chimera (and other metaphorical symbols in general) is that they also represent something within the characters. In common with a siren, these kids (especially Tina) are two things at once — their current youthful selves and the older selves they are forced to imagine.

If we read the young women of Helen Simpson’s short story as contemporary sirens, they are both of these creatures at once — tempting and terrifying.

What else is tempting and terrifying? All of us: tempting when young; terrifying when old.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “UP AT A VILLA”

SHORTCOMING

Age has always terrified the young. When we are young it’s difficult to even imagine ourselves as older. If younger selves imagine older selves at all, we see them as separate identities. When Tina whispers “Oh, gross!” at the sight of the mother breastfeeding, what exactly disgusts her? The narrator describes breasts with ‘huge brown nipples on breasts like wheels of Camembert’. Cheese is nice. But anything that’s not cheese, when compared to cheese, is not nice. Weird how that works, but there we have it. We love cheese despite itself, I guess.

Using free indirect style, Helen Simpson encourages the reader to react with disgust to the spectacle of a woman breastfeeding her newborn. This is a modern reaction. Scroll through classic art from the Victorian era and you’ll find many beautiful breastfeeding images, clearly romanticising the act of breastfeeding as beautiful, natural, life-giving and good. Simpson’s story is an inversion — contemporary life has inverted this aspect of motherhood.

So the Shortcoming of Tina is that she is disgusted by what she herself may one day become.

“She’s hideous,” whispered Tina. “Look at that gross stomach, it’s all in folds.” She glanced down superstitiously at her own body, the high breasts like halved apples, the handspan waist.

Joe and Nick have a different reaction — they are fascinated by it.

At this point Helen Simpson makes an astute feminist observation on why people don’t listen to women:

At some subliminal level each of the eavesdropping quartet recognised their own mother’s voice in hers, and glazed over.

DESIRE

Everyone at the pool wants to have a fun time.

More deeply, the woman wants to reconnect with her husband, who has retreated into himself since the birth of their baby. The young people want to live in the moment.

OPPONENT

Harvey and the unnamed mother are in marital conflict. It’s difficult to read without sympathy for them, especially the mother, who is in a very vulnerable position.

The complete lack of sympathy from the young people is striking.

The young couples came to France on a shoestring budget, buoyed by new love that didn’t last, because they’ve been let down by their surroundings. France is traditionally the country of love, but even France can’t help them. They’re each too self-absorbed to be in an adult partnership of equals (in common with Harvey, in fact).

Since the young couples want to live in the moment, the sight of older versions of themselves pull them out of that. (All are from England, cementing their more general similarity when in a foreign country.)

PLAN

We can deduce why the new parents are here — perhaps the woman suggested it, as an attempt at a brief respite from new parenthood, hoping to rekindle something from their pre-baby days.

“I thought the idea was to get away from it all.”

“I thought we’d have a chance to talk on holiday.”

BIG STRUGGLE

The married couple are failing at communication, clear from their conversation. The woman wants to talk; the man does not. The climax of their battle is when the woman howls in anger and grief.

ANAGNORISIS

The character of Charlotte has been kept silent for most of the story but after introducing her briefly as someone who has it together (aligning her with the mother), she brings her back in at the end.

Charlotte remembers a framed picture, and what follows is an ekphrastic description, cementing for the reader the subverted fairytale nature of this story:

As for Charlotte, she was remembering another unwitting act of voyeurism, a metaphorical framed picture from a childhood camping holiday.

It had been early morning, she’d gone off on her own to the village for their breakfast baguettes, and the village had been on a hills like in a fairy-tale, full of steep little flights of steps which she was climbing for fun. The light was sweet and glittering and as she looked down over the rooftops she saw very clearly one particular open window, so near that she could have lobbed in a ten-franc piece, and through the window she could see a woman dropping kisses onto a man’s face and neck and chest. He was lying naked in bed and she was kissing him lovingly and gracefully, her breasts dipping down over him like silvery peonies. Charlotte had never mentioned this to anyone, keeping the picture to herself, a secret snapshot protected from outside sniggerings.

Once again we have a description of breasts — symbolic, in this particular story, and metonyms for women at various life stages:

- The half-apple breasts of youth

- The sagging wheels of Camembert of nursing motherhood

- The full, womanly, pleasure-giving breasts of sexual womanhood

Charlotte is the character who experiences the Anagnorisis in this story, and it’s interesting that Simpson kept her quiet. She needed to be quiet to be afforded time to reflect. Unlike Tina, Charlotte realises that growing into a woman’s body is not a disgusting, terrifying thing at all. She’s had the benefit of witnessing this other image, which counteracts Tina’s commentary of this scene before them, a few years later.

The Anagnorisis in “Up at a Villa” is a great example of how a character can have an epiphany/understanding after connecting two experiences, even if the previous experience happened some time ago. In this case, the Anagnorisis phase will probably comprise a flashback or dream.

NEW SITUATION

High up on the swimming-pool terrace the little family, frozen together for a photographic instant, watched their flight open-mouthed, like the ghosts of summers past; or, indeed, of summers yet to come.

The final sentence links present time with future time, pulling that whole thread of the story together (the young are simultaneously old — that is why they fear it).

Why does Helen Simpson frame the little family statically, in a ‘photographic instant’? When the young couples run like deer, they’re not only running from the scene of the ‘crime’ — they’re running from the inevitability of youth.

So long as they’re running, by comparison that other, ‘gross’ family looks static, and behind that ‘frame’, completely separate. For this moment of running away, they can pretend they’ll never be older themselves.