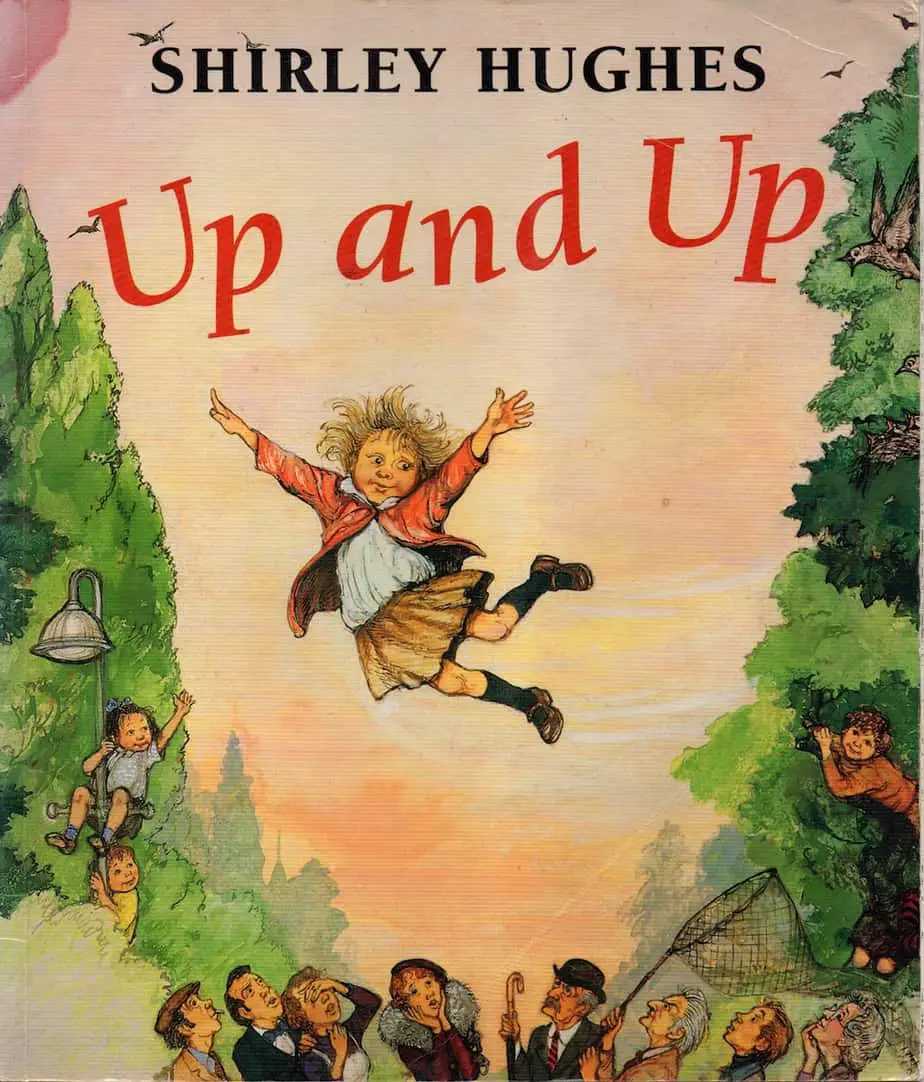

This month I wrote a post on Teaching Kids How To Structure A Story. Today I continue with a selection of mentor texts to help kids see how it works. Let’s look closely at another wordless picture book, this time by Shirley Hughes: Up and Up, from 1979.

STORY STRUCTURE OF UP AND UP

Up and Up is a carnivalesque portal fantasy, and the portal is the huge chocolate egg.

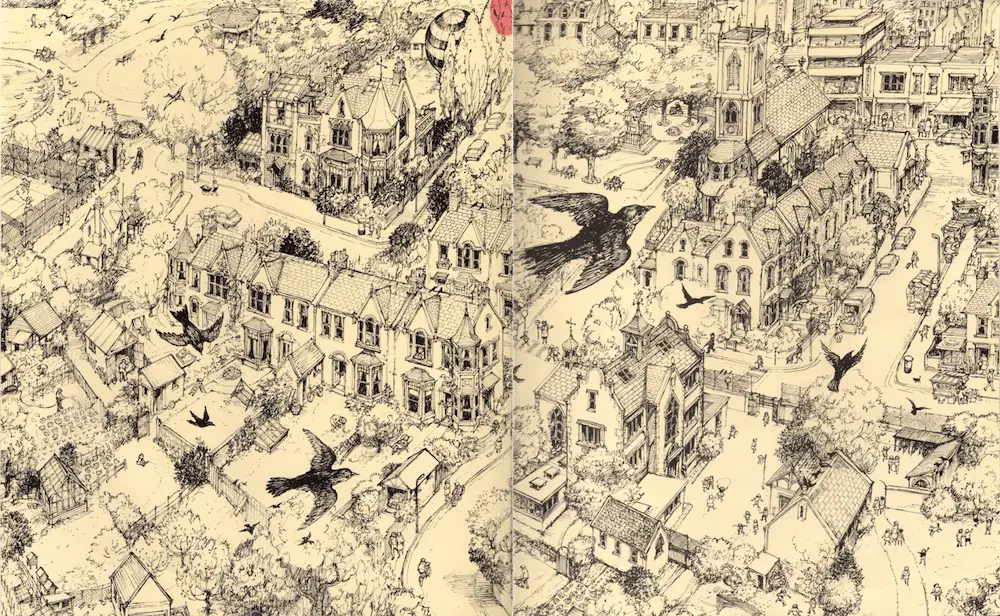

The story opens with the following wonderfully detailed Where’s Wally-esque opening spread, with foreshadowing of the big balloon partially hidden behind a tree:

WHO IS THE MAIN CHARACTER?

The girl in Up and Up doesn’t have a name, though she may be one of the characters from another Shirley Hughes book. Hughes’s characters all have a similarity to them. Children are drawn like sprightly little old people, somehow.

When characters in children’s books don’t have a name, this turns them by default into The Every Child.

WHAT DOES SHE WANT?

The girl wants to fly like a bird. We see this from the opening spread. A bird flies past; she stands up to watch it leave. At first we don’t know if she’s just interested in bird watching or perhaps feather-collecting, but the following spread cements that wish.

For more on flight, see The Symbolism of Flight in Children’s Literature.

OPPONENT/MONSTER/BADDIE/ENEMY/FRENEMY

Her natural opponent is gravity, but gravity does not make for an especially interesting opponent. We can’t care about gravity — whether it wins or loses. Gravity just is.

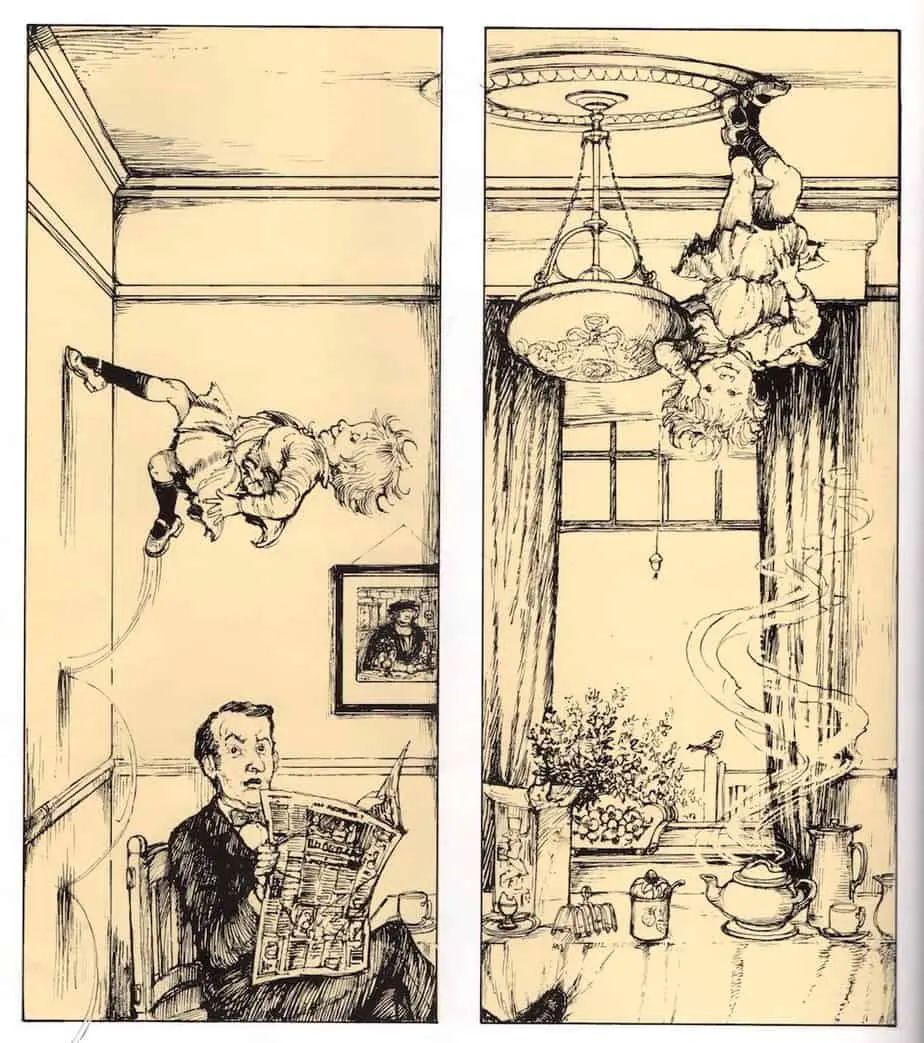

Like many children who go off on carnivalesque adventures, her parents don’t pay attention to her. I guess this is a universal feeling children have, no matter how much time parents have.

Her main human opponent is introduced a bit later — the old man with the telescope, who is the most hellbent on bringing her down. He’s a mad scientist archetype, and so keen to arrest her that he even uses his hot air balloon which he has in his backyard.

WHAT’S THE PLAN?

Shirley Hughes utilises the rule of threes during the opening sequence, giving the girl three separate plans to fly like a bird.

- Run and leap (trips and falls)

- Make wings out of paper and jump off a ladder. (I have personally done this as a kid, though I didn’t have enough faith to actually make the leap!)

- Inflate balloons and float up into the sky. (Gets stuck on a twig.) At this point the story has already crossed over into fantasy realm. First, the girl blows up the balloons with her breath, but these are behaving like helium balloons. Second, there’s no way 9 balloons would lift a girl up into a tree.

All of her plans fail so she goes home in a grumpy mood. She’s standing in her entrance hall when something amazing happens. A massive chocolate egg is dropped off by the postie.

The ‘portal’ takes the girl back into the mundane world rather than into a parallel world. The chocolate egg is something I haven’t seen elsewhere, and to be honest I’d never even realised any connection between my chocolate eggs at Easter and the fact that eggs normally house baby birds.

Though these pictures are simple black and white line drawings, I imagine this is the part in ‘Wizard of Oz’ where everything turns technicolour (or perhaps the colour has been seeping in since the balloons fantasy page). What follows is maybe a dream, or maybe it’s real within the world of the picture book. Picture book fantasies generally work like that — they can often be interpreted as the young child’s inner world fantasy.

BIG STRUGGLE

The Big Battle in this story is preceded by a chase sequence in which people on the ground are chasing the girl to see this amazing spectacle. There’s a large dose of showing off involved here — the wish fulfilment in this fantasy is ‘everyone looks at how amazing I am and I am briefly the centre of attention’.

So we can predict she will defeat the old man chasing her. It’s all part of her own fantasy of being a hero.

We never see the old man again. I guess he’s dead. (Who said you couldn’t kill people off in picture books? Just make sure it’s off the page.)

WHAT DOES THE CHARACTER LEARN?

A carnivalesque story is not about learning stuff.

You know from the beginning if a character is going to have a anagnorisis because there will be something wrong with them. They might not appreciate someone, or they might be lonely, or they might not treat their friends well. In those stories, the character will almost certainly have changed by the end.

But in a carnivalesque story the point is to escape the mundane world and have fun for a while. That’s it. The carnivalesque story structure has more in common with comic structure than with dramatic structure. Though more ‘fun’ than ‘funny’, there is nothing to be learned except ‘that was really fun’ or ‘so that’s what fun looks like’.

HOW WILL LIFE BE DIFFERENT FROM NOW ON?

The point of a carnivalesque story is that it will actually be the same as before… with one small difference. Now the girl knows what it is to have real, unfettered fun. The scene at the end where she’s eating a boiled egg and toast shows the mundane nature of her everyday life. (Boiled eggs are quite often used in fiction to show ‘ordinary’, though less so these days. I think kids are eating fewer boiled eggs in general.)