When telling a story, why might a writer choose not to name a character? If you’ve ever written an essay about a fictional work with an unnamed character you’ll realise it’s more hassle not to name a significant character than to just go ahead and call them something. Indeed there are reasons not to.

The Importance Of Names

NAMES She was Eliza for a few weeks When she was a baby -- Eliza Lily. Soon it changed to Lil. Later she was Miss Steward in the baker's shop And then 'my love', 'my darling', Mother. Widowed at thirty, she went back to work As Mrs Hand. Her daughter grew up, Married and gave birth. Now she was Nanna. 'Everybody Calls me Nanna,' she would say to visitors. And so they did -- friends, tradesmen, the doctor. In the geriatric ward They used the patients' Christian names. 'Lil,' we said, 'or Nanna,' But it wasn't in her file And for those last bewildered weeks She was Eliza once again. -- by Wendy Cope from Serious Concerns (1992)

It’s common for characters on ego-trips to insist on usage of their name. One of my primary school principals insisted on being called “Miss Jones” at the end of every single sentence. If you slipped up and said “Yes” to one of her questions, she pulled you up and required you to say “Yes, Miss Jones.” She was a lot of fun. And probably military trained.

Miss Jones was my real-life 1980s example of “I’m the god damn Batman.” Getting your name all over the place is the ultimate power trip.

But in story, outsized ego often leads to your own downfall. This is because one’s name is a metonym for honour and reputation, more so in some cultures than in others. According to the mythology of Scotland, for instance, everyone came from the one ancestral clan, passed down through the male line. Even after marriage Scottish women traditionally keep their own names, but this isn’t for a feminist reason: names are so very important to one’s identity that you can’t get a new one simply by getting married. Women are accepted as demi-members of their husbands’ families — demi because they aren’t given his name.

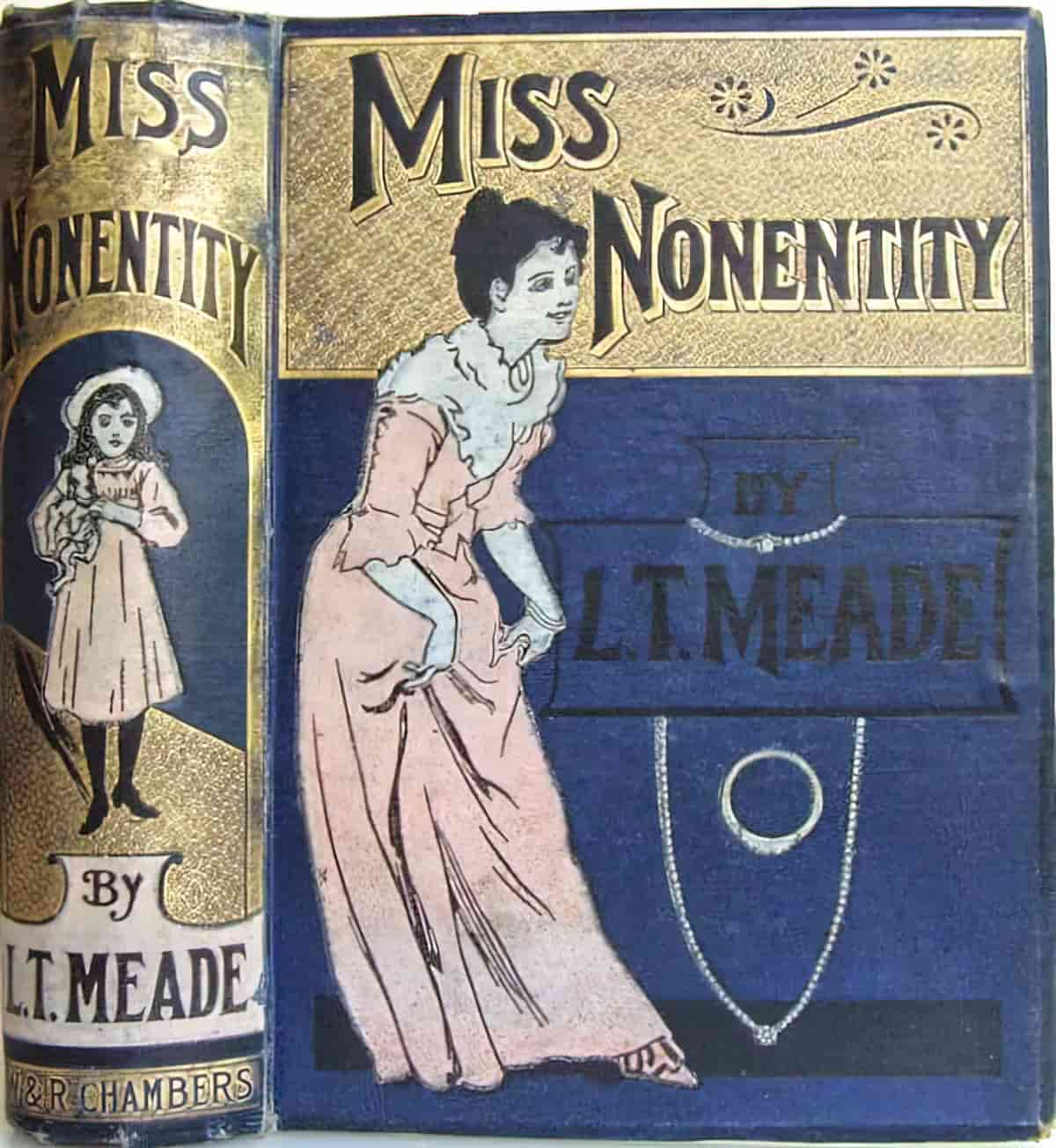

Roman women before the Empire were given no personal name; they were called by their father’s name in the genitive case, feminine form; after marriage they took the genitive form of their husband’s name: that is, they were denoted simply Marcus’s or Antonius’s, like things owned. Consider also all the portraits of a named man — John Doe, say — and ‘his wife,’ unnamed, an appurtenance to her husband.

Marilyn French, Beyond Power: On Women, Men & Morals p79

Some people even feel a spiritual dimension in regards to naming.

Stories are able to help us to become more whole, to become Named. And Naming is one of the impulses behind all art; to give a name to the cosmos, we see despite all the chaos.

Madeleine L’Engle, Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art

So why would a storyteller not give characters their own name?

To Deliberately Keep A Character Anonymous

The Norwegian/English main character in The Witches by Roald Dahl remains nameless but we never really notice until we’re required to write a book report about him. In this case, the nameless main character is a cipher for the reader, who can then more easily put themselves in their place. The boy could easily be a girl, for instance. He is the archetypal child. To give him a name would be to narrow him down to a particular child, not the child reader. This is partly why I found The Witches so terrifying as a six year old. I even examined my teacher’s hands and hair to check she wasn’t a witch.

Likewise, the narrator in “The Scarlet Ibis” remains nameless, even while the ironic symbolism of his brother’s name is mentioned within the text. This is the narrator prioritising his brother. This is also a confessional story, so perhaps we are to imagine the narrator is real but choosing to remain anonymous.

To love something, then, is to name it after something so worthless it might be left untouched – and alive. A name, thin as air, can also be a shield.

Ocean Vuong

To Deliberately Keep A Character Generic

There is a place in storytelling for archetypes and flat characters. As soon as we name a character we give them individuality. So if we want the audience to think in terms of archetype, it pays not to give them a name.

On the other hand, some names function entirely generically. Across English fairy tales the name Jack meant ‘archetypal, unmarked boy’. See Jack and the Beanstalk, for instance. (The female equivalent is Jill, but girl characters can never be truly ‘unmarked’ owing to them being marked with female-ness.) John is equally generic, but less working class. The female equivalents are Jill and Jane. The German boys of fairytale were generically called Hans.

“Beauty and the Beast” also relies on fairytale archetypes, named for abstract qualities. This emphasises the allegorical nature of the tale. Even in modern revisionings, in which storytellers sometimes give these archetypes individuating names, their archetypal characterisation perseveres.

Paul Jennings made use of generic Australian 1980s names in his short children’s fiction. These names may seem generic, but are clearly white.

Katherine Mansfield does not name the main character in her short story “The Little Governess“. This turns the story of a young woman alone into a more universal female experience.

Another example is Closet Land from 1991, in which the abuser male and abused female remain unnamed. This is an attempt to universalise the dynamic, though it ultimately subverts nothing.

To Keep Them From Seeming Important

Sometimes, and this is a really big myth, sometimes we’re afraid to name experiences or feelings because we think naming them gives them power, and if we’re feeling something hard or uncomfortable, the last thing we want to do is give it power. Let me dispel this myth now with 400,000 pieces of data and 20 years of research. When we name and own hard things, it does not give them power, it gives us power.

Brene Brown

Naming has primary importance as a way of determining a being’s subjectivity. [A character’s namelessness] reinforces his lack of an existence, his lack of agency.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Waking Sleeping Beauty

Writers choose details for different reasons, and one detail might be offering up character names. Sometimes writers want to make a setting seem real, and will give details for that reason alone. Recently I wrote a story which mentioned two children by name — characters who I’d individualised slightly hoping to show the smallness of the community, but who were not going to appear again later on.

A critique partner questioned my decision to name these characters. Especially because I happened to name them early in the story, the reader was primed to try and remember them, expecting them to pop up later. I removed the characters altogether rather than face the dilemma of how to introduce community characters without also accidentally giving the impression the reader is meant to remember who they are.

In short, readers intuit they won’t have to remember the kettle is ‘blue’, and will happily accept that kind of detail as background. A blue kettle may be symbolically significant but nothing more. It is more problematic to name background characters hoping a reader to do the same. We are naturally sentiocentric.

In “The Little Governess” Mansfield doesn’t name the porter, the waiter, either. This is more expected. They’re minor characters, and she interacts with these men as their work roles.

When re-visioning old tales, writers often give names to previously unnamed characters.

Stories can end up with too many characters for all sorts of reasons, but new authors are especially drawn to adding characters to represent the protagonist’s social and familial circles. When these characters don’t have distinct roles in the plot, they blur together and get harder to remember while still taking up some of the audience’s precious attention span.

Five Tropes That Sound Cool but Rarely Work from Mythcreants

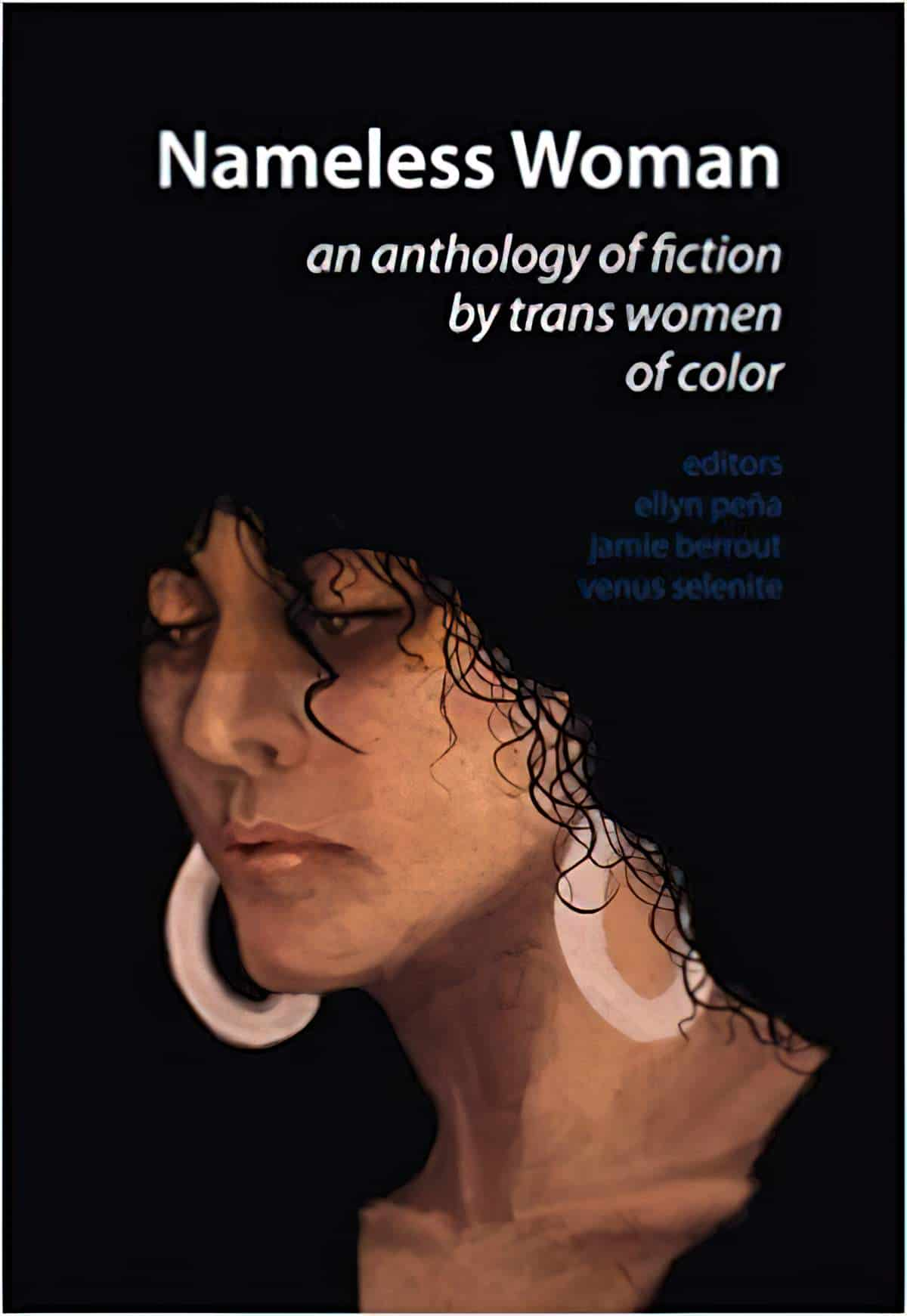

Accidental Symbolic Annihilation

Some years ago I wrote a story in which I named the main male character but didn’t name his wife. The storytelling reason for this: I wanted to keep the wife from seeming important to the plot. To give her name would be asking the reader to remember yet another name. But when I put it through critique, a (fellow) feminist critique partner was insulted that I had not named the wife and refused to read further. She had grown sick and tired of reading stories about men. An unnamed wife was a bridge too far.

This brings up an interesting point. Throughout history, certain demographics have been left out of stories, and not just fictional ones. This is part of a (mostly) subconscious ploy to uphold white patriarchy. Women’s scientific breakthroughs have often been attributed to adjacent men, oftentimes in a variation on the Pygmalion story, in which a successful woman must be the product of a man.

In short, you will come under increased scrutiny if you avoid naming an historically marginalised character than to avoid naming a white male character. This holds true even if you can justify why you did what you did in storytelling terms.

To Highlight Problematic Invisibility

One good political reason not to name a character: To highlight to the reader that this character is ignored, downtrodden and marginalised in society.

An example of this can be seen in “The Home Girls“, a short story by Australian writer Olga Masters about two young girls who are shunted from foster home to foster home. Jarringly, Masters refers to the sisters as ‘the fat one’ and ‘the thin one’. An ungenerous reader might think the author’s fatphobia is revealed in this description.

My take: Masters is highlighting the tendency for people to regard these unknown girls only after the briefest, impressionistic glance: BMI is a shallow and offensive way to describe a girl, and Master’s narrative voice is The Village Voice.

We are now living in an era where commentary on other people’s weight is taboo. Masters published her short stories in the 1980s, and I wonder how many writers would be brave enough today to trust readers’ ability to separate narrative choice from author’s voice.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I also just found out that you actually did provide Offred’s name in [The Handmaid’s Tale]; I’m shocked. On social media —

ATWOOD: No, I didn’t.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: June isn’t her name?

ATWOOD: No. She doesn’t have a name in the book. The readers figured out what the name was, so I had to accept their verdict. They did a piece of reasoning which goes like this: There are a number of names mentioned in the first chapter, and of all of those names mentioned, only one of them isn’t mentioned again. So they figured it had to be her. But that was them; it wasn’t me.

However, the show adopted that, so it’s a question of readers adding in something that is in the book, but it wasn’t in the mind of the writer consciously. I’ve got nothing against that because it doesn’t contradict the text. It adds something in.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Yeah, I didn’t like that because I was like, no, the whole point is that she never gave her name and her daughter’s name.

ATWOOD: No, she doesn’t.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Yeah.

ATWOOD: She doesn’t in the book, but the readers decided that that must be her name. But they’re not in the book.

Margaret Atwood in conversation with American economist Tyler Cowen (2019)

The stories in this anthology confront major themes and issues in the lives of trans women of color with profound honesty and attention toward helping one another heal. A story like “The Girl and the Apple,” by Jasmine Kabale Moore, not only unflinchingly describes the sense of ever-present danger that many of us feel in public spaces (including the hyper-vigilant condition of trauma that results from repeated exposure to intense scrutiny and violence) it also provides invaluable emotional support to other trans women of color by accurately reflecting, and therefore validating, our experiences and our perceptions of reality. A number of other stories explore their own kinds of traumas and begin to show us a way to survive them, a day at a time. In contrast, there are also stories in our anthology that take up a completely different subject matter – genre fantasies, memories and the past, self-acceptance, relationships with family and friends, romance and intimacy, and language itself – but they do so in the specific context of our lives as trans women of color.

No Name, Incomplete

In antiquity, to know someone’s name was to have some kind of power over them. This is seen very clearly in “Rumpelstiltskin“.

Toni Morrison utilised this universal mythology in her novel Beloved, drawing on ancient African and Indian mythologies about child-demons. In Beloved, Sethe murders her baby to prevent her from being taken by slave drivers. The ghost of this baby never goes away, interfering in every aspect of Sethe’s life. Significantly, the baby is never given her own name, known only as “Beloved”.

That’s because, in mythic stories, a character never named remains incomplete. Superstitiously, to be incomplete is terrible. And pretty much the worst thing you can be is an incomplete woman. Across mythology, an ‘incomplete’ woman includes a woman who hasn’t given birth. Maybe this is because she died a virgin without having babies of her own (e.g. the Greek ogre of Lesbos, Gello). In that case, she’ll come back to wreak havoc upon corporeal beings, killing other people’s babies, eating them up.

Honestly, what else is she meant to do? The incomplete woman doesn’t belong here, but nor does she belong in the world of the dead. According to The Odyssey, she’ll wander forever between both worlds.

This category of dead people was known as the aoroi.

Oh, the aoroi did have one use — for us, at least. Earthlings could summon these incomplete beings during rituals. The aoroi were useful as go-between messengers. In ancient Greece and Egypt it was thought that the underworld surrounded its inhabitants by walls, but these aoroi had no walls around them. Any decent magician could summon them back to Earth for a bit.

In Christianity it is also terrible to be incomplete (unbaptised). This will leave you vulnerable to evil. So it’s no accident that the baptism ceremony is also a kind of naming ceremony. There is generally a public naming of the child and a sprinkling of water over the babies forehead.

To be baptised is to be named; to be named is to be complete. As a general principle, naming equals completion.

The Name Is Gained As Part Of The Character Arc

A wonderful example is The Adventures of Beekle: The unimaginary friend by Dan Santat, about a creature who doesn’t fully exist in the world until he finds a real child to imagine him up. It is only then that Beekle gets his name. With his name comes identify, belonging and a sense of purpose.

THE “I KNOW YOUR TRUE NAME” TROPE

You will see this trope across fairytales. The stand-out example: Rumpelstiltskin. When the princess discovers the goblin’s name she has won the Big Struggle.

In the classic Rumpelstiltskin plot, the princess hasn’t simply learned the goblin’s name: She has learned how mean he really is. She’s got the measure of him. The name stands for True Self.

When you’re really, really bad, the act of being known is in itself a destructive act. Ironically, the really, really bad character puts up the challenge: See if you can work out who I really am. Bet you can’t. I’m smarter than you, after all.

The trope can also be seen in myths from antiquity, such as the story of Lilith, who had a number of secret names. When Elijah learned her names — and also the nature of her evil — he had the upper hand.

There’s a really old storytelling trope: A trickster girl — and it is usually a girl — overcomes an Opponent with word play rather than physical tousle. Oftentimes the ‘word play’ is simply guessing the opponent’s real name.

This post contains Breaking Bad spoilers. But hopefully you’ve already seen that if you wanted to.

In storytelling, to lose your name is one way of losing your identity. This is utilised by Hayao Miyazaki in Spirited Away when Chihiro becomes Sen when she starts working at the bathhouse. She will only get her name back after she proves her dedication to hard work as the salve to all of her problems.

There are other ways storytellers convey the idea that losing one’s identity is the worst. In Peter Pan and Wendy (and later in Hook) to grow up is to lose your identity. However, it’s interesting that the loss of name, or replacement of ‘real’ name with ‘nick name’ often happens in stories where your identity is more generally lost.

By the way, ‘nick name’ used to be ‘a name given in ridicule or contempt: from the French nom de nique. Nique is a movement of the head to mark a contempt for any person or thing. (From a 1703 dictionary of slang.)

The Say My Name Trope In Contemporary Storytelling

You’ll see the Say My Name trope in contemporary storytelling — not just in old fairytales.

It often goes hand in hand with shapeshifting: Once the hero(ine) says the opponent’s name, the opponent may change into something else.

SPLIT(2016)

Recently I watched Split (by M. Night Shyalaman) and noticed the initial Big Struggle scene was Rumpelstiltskin-esque. Spoiler (actually the film spoils itself — I have several issues with it, politically): the abducted surviving heroine finds a note from the baddy’s newly murdered psychologist instructing her to use the baddy’s real name in order to snap him out of his dissociative state.

Kevin Wendell Crumb!” she chants. “Kevin Wendell Crumb!” This sends the DID (dissociative identity disordered) opponent into a tailspin and precipitates a (long, drawn-out) big struggle between the forces of good and evil.

The baddie changes into The Beast. Shapeshifting.

Straight out of Rumpelstiltskin.

BREAKING BAD

“Say My Name” is the title of the seventh episode of Breaking Bad in its fifth season. So, Walter White is almost dead now.

The episode was originally titled something different, but the writers room must have intuited how great that quote is, and pulled it for the episode title.

“Say my name” refers to Walter’s demand for Declan to call him Heisenberg during their confrontation by urging him to “say my name”. Some viewers have called the Say My Name scene Walt’s ‘Icarus Moment’, when his ego is at its peak. (Icarus is more broadly about ego. I’m after a name more specific when referring to this trope.)

Walter White, like Rumpelstiltskin, is on a power trip. And like Rumpelstiltskin, he’s about to meet his maker. In many versions of the fairytale, Rumpelstiltskin dies after stomping in fire. (Nope, in fairytales stomping on fire does not put the fire out — it puts you out.) In Breaking Bad, Walter is also ‘put out’ in a blaze of fire (gun fire). So is Hank, his foil.

By the airing of the “Say My Name” episode, everyone (including me) was waiting with bated breath to find out how Breaking Bad was going to end. Only in hindsight, everything was right there for us, leading to exactly that ending. If I’d seen the Rumpelstiltskin connection, and how Walt was so insistent about people knowing and using his name, I’d have predicted his fate.

This is how writers make endings feel both surprising and inevitable. I wonder if even the writers made the Rumpelstiltskin connection, or if they were telling the story of Walter White at a deeply subconscious level.

(The Breaking Bad writers made use of many more fairytale tropes.)

For more examples, see the I Know Your True Name entry at TV Tropes.

Why is this trope so enduring?

Just guessing here, but maybe angry mothers have been calling children by their full-names literally since children EVEN HAD full names. When our mothers call us by our full names we don’t call that a trope, but in fiction it’s known as the Full Name Ultimatum. Full names are scary!

In her book From The Beast To The Blonde, Marina Warner has a more considered answer for us. First, she begins with by describing a main function of fairytales:

Fairy tales […] concern themselves with sexual distinctions, and with sexual transgression, with defining differences according to morals and mores. This interest forms part of the genre’s larger engagement with the marvellous, for the marvellous is understood to be impossible. The realms of wonder and impossibility converge, and fairy tales function to conjure the first in order to delineate the second: magic paradoxically defines normality. Hence the recurrence, in such stories, of metamorphoses, disguises and above all the impossible tasks—the adynata—of folk narrative.

Did you know what adynaton is, as literary technique? (Me neither.) Now we get examples:

These can take an active form: that the protagonist should fill a crippled pail with four-leaved clovers, as in Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy’s ‘Serpentin vert‘, or that the quester should come neither clothed nor naked, neither riding nor walking, neither bearing a gift nor not bearing one.

This is all part of a wider chapter about The Queen of Sheba, a character from the Bible.

This riddling demand, made in traditional tales in many different languages, was given to King Solomon and the Trickster Marcoulf in medieval texts, and to the poor peasant’s clever daughter in the Russian fairy tale, collected in the nineteenth century. Verbal riddles do not always invite performed solutions, but Sheba’s to Solomon do, and in her role in these stories she takes the place of the lowlife, cunning figure, like Marcolf, or the quick-witted peasant girl, as she tries to have the advantage over Solomon. This riddle is solved when the subject of the challenge rides on a goat (or a hare), with one shoe off and one shoe on, one leg on the ground, draped only in a net, and carrying a hare (or a quail) which springs to freedom as soon as he or she arrives.

The riddling story is found all over the place, Warner explains:

The riddles posed by Sheba relate to the matter and the manner of many fairy tales, which dramatise ‘witches’ duels‘: in these the heroine or hero confounds the powers of fairy evil by surpassing them in verbal adroitness, in tricksters.

The Devil is the ultimate trickster.

The Devil turns tricks, but those who elude him can outsmart him at his own game.

The Elfin-Knight is a famous Scottish ballad. (This trope seems especially popular in Scotland. The tale of Whuppity Stourie is the Scottish version of “Rumpelstiltskin”.)

In one of the highly popular ballad versions of ‘The Elfin-Knight’, for instance, a story which exists in different forms all over the world (the most famous being ‘Rumpelstiltskin’, hero of the Brothers Grimm’s popular tale of that name), the heroine wrestles with the Elfin-Knight, who would snatch her away to the underworld as his bride, by using her verbal wit against his power. The Devil who has come for her in marriage sets her ten riddling questions, and she replies staunchly to all of them. […]

This all relates back to a religious view of earlier times. People really did used to believe this, hence the entire concept of blasphemy:

Only God can remain the Unnameable: naming the Devil, knowing him for what he is, undoes his power.

Nickname Only, Individuality Denied

A variation on the decision to avoid naming a character is to give them only a nickname. This can also have the effect of removing power.

The Narration Stays Close To A Certain Character

And the character wouldn’t know the names, either, or may have forgotten them.

Talking about her short story Omakase, Weike Wang was asked this question:

These two characters are referred to in the story only as “the woman” and “the man.” Why did you choose not to name them?

and replied:

I am terrible at naming characters. But, in this case, I thought about the setting. The chef is unlikely to know the names of the customers. He might ask but then quickly forget. I also thought it would make for a nice contrast that the three of them have a friendly but somewhat abnormal conversation without knowing one another’s names.

FURTHER READING

For as long as ZJ can remember, his dad has been everyone’s hero. As a charming, talented pro football star, he’s as beloved to the neighborhood kids he plays with as he is to his millions of adoring sports fans. But lately life at ZJ’s house is anything but charming. His dad is having trouble remembering things and seems to be angry all the time. ZJ’s mom explains it’s because of all the head injuries his dad sustained during his career. ZJ can understand that–but it doesn’t make the sting any less real when his own father forgets his name. As ZJ contemplates his new reality, he has to figure out how to hold on tight to family traditions and recollections of the glory days, all the while wondering what their past amounts to if his father can’t remember it. And most importantly, can those happy feelings ever be reclaimed when they are all so busy aching for the past?SEE LESS

- Symbolic names are a common feature of fiction.

- Names are one thing — in children’s literature in particular the writer must also introduce the character’s age somehow.

- The Science of Baby Name Trends: What makes a name suddenly pop—and then die? Social scientists and historians have been puzzling over this for decades. From JStor Daily

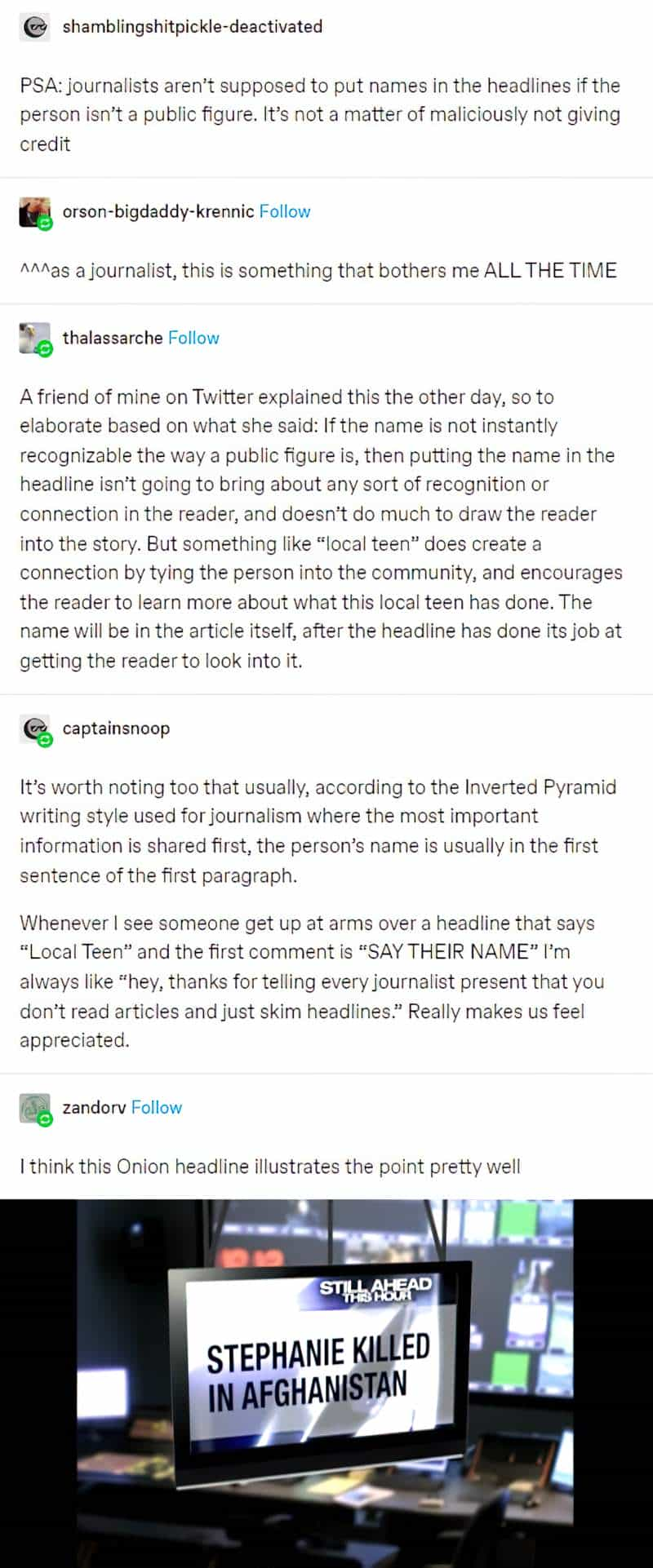

WHY JOURNALISTS LEAVE PEOPLE UNNAMED IN HEADLINES

Header: Rumpelstiltskin illustrated by Edward Gorey