“Uncle Einar” is a short story from Ray Bradbury’s well-known short story collection October Country (1955), but was first published in his Dark Carnival collection (1947).

We’ve already met Einar as Timothy’s uncle in “Homecoming“. Now we see the man at home, and learn more about the realities of living as a supernatural being in a world made for regular humans. Which of these stories to read first? It really doesn’t matter. In October Country “Uncle Einar” appears first. But in Bradbury’s Collected Stories Volume One, “Homecoming” appears first.

Below, I compare and contrast “Uncle Einar” with two stories from completely different eras: “Rip Van Winkle” (1819) and Pixar’s The Incredibles (2004).

SETTING OF “UNCLE EINAR”

The world of the story is simple: Somewhere in rural USA, mid 1940s. More interesting to consider for this story is the era in which Bradbury was writing, and that Bradbury was himself a man.

Ray Bradbury wrote this story in the wake of World War 2. There’s nothing like a war to bolster the image of men as strong, musclebound, emotionally tough. And there’s nothing like a post-war period to ram home an essentialist gender binary in which women are required to be strong on the home front, while men achieve self-actualisation by leaving the feminized space of home, and go out into the world to utilise and perform their masculine-coded traits.

In these environments, unless men get the opportunity to expend their masculine superpowers, they spend their lives in a depressive slump, like caged birds.

When analysing Homecoming, I noticed a link between Bradbury’s short story and the 2004 Pixar film The Incredibles. As in “Homecoming”, The Incredibles features an ensemble cast in which members of a family each have their own superpower.

In 2004, The Incredibles was widely lauded by reviewers for (shock!) being a mainstream film starring men and women, boys and girls. The phrase “great ensemble cast” was bandied about. Few reviews found anything wrong with the storyline at all.

Except this one, from The F-Word (in which the F stands for feminism). Read the following snippets about The Incredibles and map it onto Ray Bradbury’s “Uncle Einar”:

The message…appears to be that the secret to happy family life is for men to get more fulfilling jobs.

The statement ‘moms have to stretch in 100 different ways each day’ is of course often correct; the problem is that Bird seems to view this an as exemplary situation rather than an injustice to be rectified by forcing men to shoulder a greater share of childcare and housework.

The F-Word 2005 review of Pixar’s The Incredibles

Of course, Ray Bradbury was writing the hegemonic masculinity of his era. The Incredibles is far more recent. (A bunch of things have come to light about the Pixar men since then. Makes sense now, right?)

STORY STRUCTURE OF “UNCLE EINAR”

SHORTCOMING

There’s a good chance Ray Bradbury chose a symbolic name for Uncle Einar:

The name Einar is boy’s name meaning “bold warrior”.

With Norse (and pseudo-Norse) names such as Thor, Odin and Magnus growing in popularity, this one, which refers to warriors destined for Valhalla on account of their bravery, might have some appeal outside Scandinavia.

from a baby name website

Einar’s is presented as a natural brave warrior, yet his wife wants him to use his superpower to help dry the household washing. Einar, like any typical 1950s husband, considers all the washing his wife’s job: “I’ll not be pierced by lightning just to air your clothes.”

Bradbury’s “Uncle Einar” reminds me of “Rip Van Winkle“.

- The narrator knows how terrible the man is. Even so, he experiences no self-revelation which would make society better for everyone, and especially for women.

- Both do stupid things after drinking. (In “Rip Van Winkle” alcoholism is implied; here Bradbury notes ‘after too much crimson wine’.)

- The story-within-a-story format

- Dame Van Winkle is a renowned ‘nag’. Bradbury has much sympathy for Einar’s wife, but her request he help him with the washing is nonetheless a huge imposition.

- As in “Rip Van Winkle”, he falls asleep near a bush. (Here it is an apple tree.) Instead of small men, this is when Einar meets his wife, with magical witch healing skills.

- The man flying a kite and bonding with someone else’s kid (in this case it’s Timothy from “Homecoming”). Note that the story is titled “Uncle Einar”, not “My Dad With Wings” or something which would suggest Einar is a full and loving presence in the lives of his own children, despite occasional tales about his life of freedom before he was married.

DESIRE

The ability to fly is a very common wish fulfilment fantasy. Flight is generally a proxy for absolute freedom. It is cruel to keep a wild bird in a cage. Likewise we extrapolate a man with wings must be allowed to use them.

OPPONENT

Einar’s ‘sweet wife’, for wanting her husband to at least help with the housework. She clearly understands her husband’s weakness, and threatens to hang them about the house to dry them. Ray Bradbury puts Einar’s fragile masculinity right there on the page for us:

“So it’s come to this,” he muttered, bitterly. “To this, this…” […] That did it. Above all, he hated clothes flagged and festooned so a man had to creep under on the way across a room.

“Uncle Einar”

I believe the word ‘man’ is doing double duty there. Universally, ‘a man’ means ‘people’. It also refers to the particular humiliation experienced by men, as a gender, seeming smaller, lowering themselves to the height of women and children.

Einar’s wife is named Brunilla Wexley via the flashback; marriage has had an anonymising effect on her. In the present timeline, in which she is married, she is Einar’s ‘sweet wife’.

A strange arithmetic takes place when we think about the equality (or otherwise) in a narrative. Note that Brunilla is the one who saves Einar’s life, both literally (from the transmission tower), practically (by providing the housework and children which allow him to soar) and spiritually (implied by her standing on the ground, watching Einar in the air, not even from The Hill but from the domestic confines of their back yard). Bradbury’s wife is the perfect wife. Like flight itself, this woman is a hetero-masculine wish-fulfilment fantasy.

Does a wife saving her husband make this story feminist now? Nope.

- Brunilla is peak Female Maturity Formula (notoriously favored by Pixar)

- Brunilla exists without freedom, anonymised within matrimony. Einar’s freedom-entrapment narrative goes from Entrapment to Further Entrapment (via the flashback) to Freedom. Brunilla has no such arc: Entrapment, Entrapment, Entrapment. Moreover, the story does not acknowledge this. As in The Incredibles, the writer tries to Band-Aid over the misogyny by including a feminist line about women’s equality. At the start of Pixar, the wife scoffs at the idea of settling down (then settles down). In “Uncle Einar” Brunilla says, “But one day I’ll break out, spread wings as fine and handsome as you.” Einar tells her, “You broke out long ago,” meaning her identity is entirely wrapped up in existing as his wife.

- Bradbury tells us numerous times that Brunilla is ugly. Of course, Einar doesn’t find her so. (Now he’s been disabled after his accident he probably considers himself on the same level of the marriage market and is in need of a mothering type who’s grateful to have anyone at all.) But I’ll go with Brunilla’s own assessment of herself for the ‘reality’ of the situation. Brunilla feels keenly that her looks aren’t up to par. Bradbury encourages the reader to believe that Brunilla is ugly within the world of the story, but isn’t Einar grand for loving her regardless. What I prefer to see subverted in fiction and seldom do: The notion that women are not ornamental, and also acknowledgement that lookism is a real prejudice which has real consequences for people, especially women. (For men it’s mainly height.)

Society is the bigger opponent. Einar must keep his superpower hidden, yet it’s too dangerous to fly at night. He has previously almost killed himself flying into a high-tension tower (a.k.a. a transmission tower).

PLAN

The children happen to be flying kites one day. Their plan to have fun on a windy day will have unexpected results.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

This guy is a gigantic, sulking cry-baby. (Why on earth is he Timothy’s favourite uncle in “Homecoming”? My guess: the nephews love him because he played with them when they were little, Rip Van Winkle style. He whinges the entire time. Here he is, ‘festering under an apple tree’:

Was his only flight to be a drier of clothes for his wife, or a fanner of children on hot August noon?

“Uncle Einar”

The story-within-a-story contains the life-and-death struggle in which Einar’s wife saves him from death.

The climax is the local kite festival.

ANAGNORISIS

If Ray Bradbury thought Einar should pull his head in, confident in his stable sense of self, he’d show Einar making good with his wife.

But no. Einar is happy now because he has it all: the perfect wife who completes him, and also the ability to use his wings (proxy for any masculine power which takes place outside the home).

This completes him. Importantly, his children are proud of him now: “Our father made it!” cried Meg and Michael an Stephen and Ronald, in which ‘made it’ has three different meanings:

- Einar constructed the kite (not actually true, but this is how it’s taken by the others)

- Einar has used his own body as a kite (the fantasy, comical reading, specific to this story)

- Einar has ‘made it’ as a proper man.

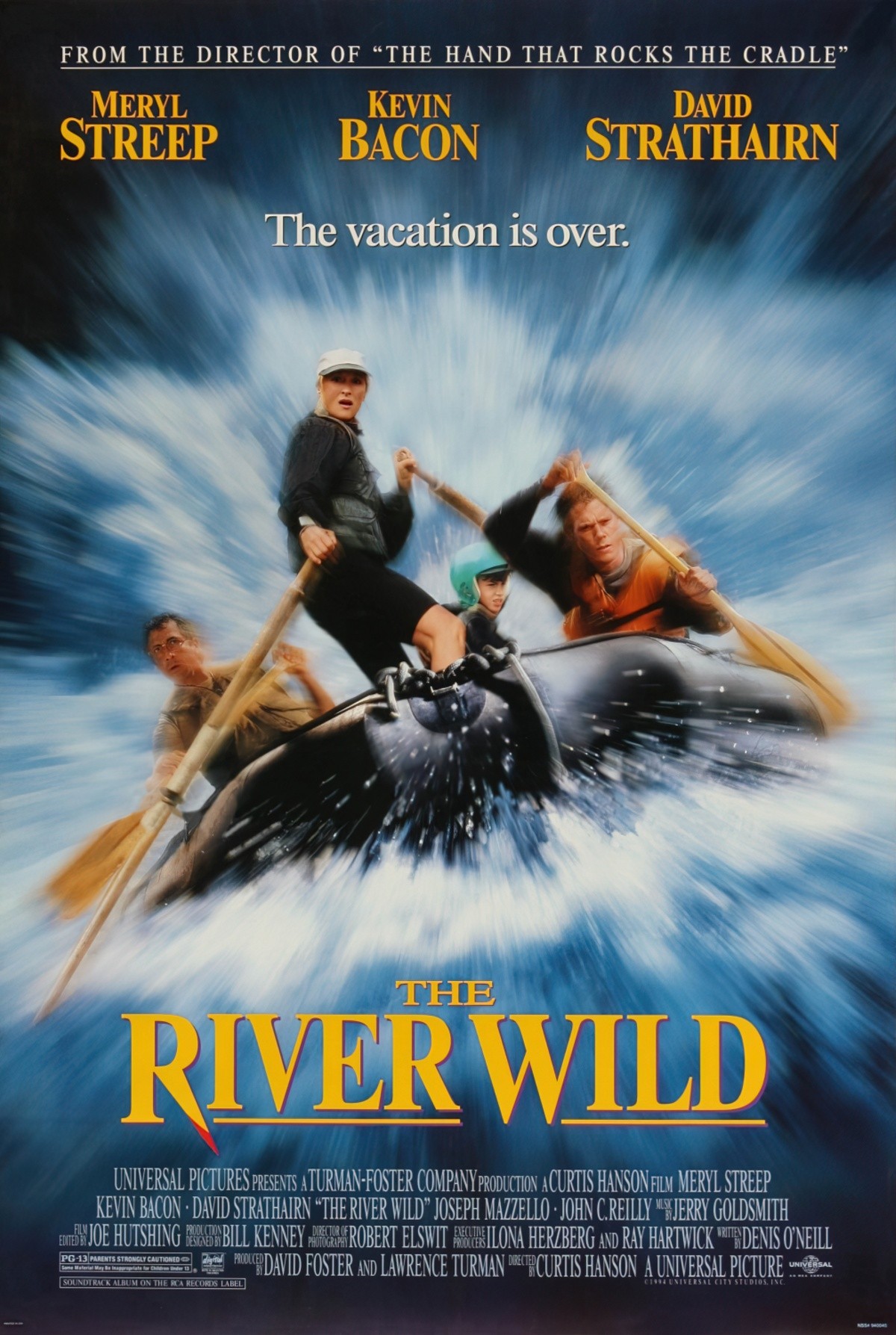

Reminds me of the end of The River Wild (1994). After Meryl Streep’s character demonstrates superhero strength, Hollywood must preserve masculinity at all costs. The father has turned up and eventually helped to set up a booby trap for the raft.

The son is asked by a reporter: “So were you scared, Rourke?”

Rouke says, “Only of Wade and Terry. But I wasn’t scared of the river. I knew my mom could handle the river.”

“And she brought you through the Gauntlet herself?”

“Yeah.”

“What about your father? What did he do?”

“My dad? He saved our lives.”

HIGHLY F*CKING DEBATABLE. If you haven’t seen that film, Meryl Streep almost drowned during filming, which is all you need to know about who saved the family. However, the film-makers gave the son and his daddy-idolisation the last word, hoping to leave audiences with the impression that the father was far more help than he actually was. By bringing the super-achiever mother down, the father can regain his rightful place as head-of-family. In that 1994 story as in Bradbury’s older one, a man is miserable, morose and of no help around the house until someone recognises superpowers supposedly associated with manhood.

NEW SITUATION

We are to believe the household has been restored to its natural and proper equilibrium with a wife in the home, happy children who like to fly kites and a husband who is emotionally and spiritually fulfilled. Discovering a way to fly without consequence is also gender affirming for Einar. (Not a phrase that existed in the mid 20th century, but feel free to apply it more broadly than to the trans community — cishets do gender affirming stuff all the damn time.)

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Do you think Einar’s masculinity is tough enough to withstand the odd spot of housework now? Or will he keep crying every time his wife asks him to shoulder just a tiny fraction of household tasks?

I know what I think, based on how women were forced out of the workforce and back into homes during the decade which followed.

RESONANCE

Well, I’d like to say stories like this died in the 20th century but the Pixar example is just one of many.

In DreamWork’s Shrek Forever After (2010), Shrek is another middle-aged male character who finds himself frustrated with his domesticated lifestyle as a husband and father of three. (The bit of good news here is that Mike Myers’ kids — the actor who voiced Shrek — can’t stand the Shrek films.)

Stories in which feminine coded tasks around the home hem men in continue to proliferate in tentpole, conservatively funded storytelling. Keep your eye out for it.

ILLUSTRATIONS OF KITE FLYING