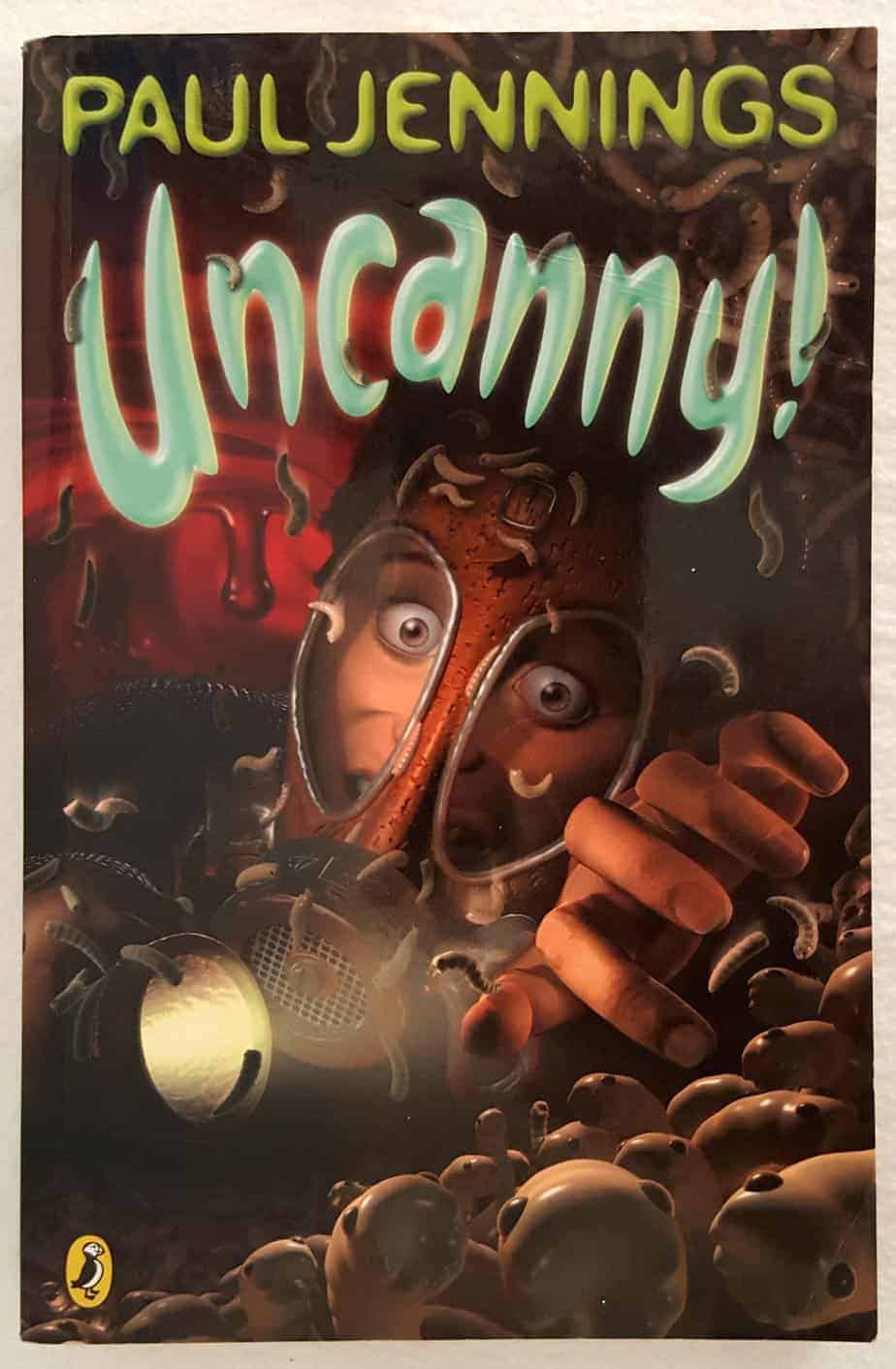

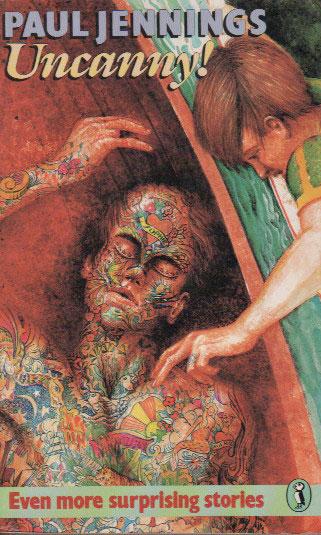

Uncanny is a hi-lo short story collection by Australian author Paul Jennings, first published 1988.

The original ‘uncanny’ stories were by British writer May Sinclair (1863 – 1946). I read a collection of Sinclair’s uncanny short stories (1923) a few years ago and wasn’t really moved by them. This is because so many writers have emulated Sinclair’s work that hers no longer feel all that original! Sinclair was a heavy influence on H.P. Lovecraft. Now, I wager you’ve heard of him, even if you haven’t heard of her.

Unfortunately, the influence of May Sinclair remains little known. Plus, her writing career was cut short with the onset of Parkinson’s disease in the late 1920s.

The Uncanny May Sinclair stories have plots like this:

- Two lovers are doomed to repeat their empty affair for the rest of eternity.

- A female telepath is forced to face the consequences of her actions.

- The victim of a violent murder has the last laugh on his assailant.

- An amateur philosopher discovers that there is more to Heaven than meets the eye.

Likewise, Jennings writes ‘circular’ stories in which stories end on the note that this weird thing will continue on forever. Characters in Paul Jennings stories are forced to face the consequences of their actions. Underdogs (victims) get the last laugh against their opponents. The stories are set in snail under the leaf settings, where there is more to ordinary life than meets the eye.

Whether directly or indirectly, May Sinclair had an impact on Paul Jennings, across all of his short fiction, and not just in this particular title.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “ON THE BOTTOM”

The twist of “On The Bottom” a real groaner. It ends with a dad-joke. It also has an ending typical of picture books, with the main character left with a souvenir from a highly improbable journey.

SHORTCOMING

Lucas has a father who doesn’t treat him like an adult. The father steps in to pull a fish in when Lucas is capable of doing it himself.

His problem is that after he finds the finger, he has a tattoo on his own finger. This means he’s in trouble.

DESIRE

Lucas wants to be a man and catch his own fish. This means preparing them as well.

OPPONENT

The mystery in a story is set up at the same time (or instead of) the opposition.

Lucas finds a finger inside the shark.

PLAN

Following directions from his bear tattoo, Lucas finds a tattooed man lying flat in his dinghy far out to sea, almost dead.

BIG STRUGGLE

The tattoos transfer to Lucas which means he is ostracised. He is in danger of being taken away from his father. He comes close to a psychological death when he becomes a hikikomori in his own house.

ANAGNORISIS

The tattooed guy turns up, reveals he’s from the circus, and with a handshake he can get his tattoos back.

NEW SITUATION

Lucas is now free of tattoos, except for one under his underpants. This is a trope used in plenty of fantasy picture books — the main character is left with a souvenir to prove it all really happened, should the reader ever ask. Chris Van Allsburgh uses this in The Polar Express when the boy comes back to his bedroom with a souvenir from his train journey. Margaret Wild also uses it in There’s A Sea In My Bedroom.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “A GOOD TIP FOR GHOSTS”

The ‘tip’ in “A Good Tip For Ghosts” refers to the local refuse station. I remember tip trips as a kid, and I’m familiar with the sort of person who loves fossicking around in them. There used to be a corner for stuff which other people might want. If it wasn’t entirely useless, you’d put it there. But our local tip has recently put up signs to say no one’s allowed to take anything away. Health and safety. But nobody listens. We live in a semi-rural area, so all sorts of farm castoffs can be found at the tip — trellises, chunks of scrap metal and the like. I know people who have designed their gardens with stuff from the local tip. The father in this story is that kind of guy.

SHORTCOMING

The narrator is embarrassed by his father’s rusty old car and how he fossicks around in the rubbish. He is humiliated by their own poverty, or the appearance thereof. This humiliation is never subverted, unfortunately.

DESIRE

The narrator wants to make a good impression at his new school, because the family has only just moved to this area.

OPPONENT

The father, who is embarrassing him in front of a rich kid.

The policeman who pulls them over at first may function as an opponent but he turns out to be friendly. Jennings uses the policeman as a storyteller. This turns him into a false opponent ally, though it does turn out he’s got the story slightly wrong.

Gribble, the archetypal school bully who sets up an initiation challenge.

Old Chompers is the big bad supernatural opposition. We assume he ‘chomps’ children to death.

PLAN

The twins talk about ways to get out of doing the challenge. I believe this is the main reason Jennings chooses twins. As in “Birdscrap”, the boys talk through all the reasons why they’re going to have to go ahead with this challenge of a midnight trip to the tip.

BIG STRUGGLE

They meet Old Chompers and give him back the false teeth which Gribble gave them at school.

ANAGNORISIS

The twist is that Old Chompers is not searching the tip for his lost grandsons at all. He has been searching all this time for his false teeth.

NEW SITUATION

An epilogue section finishes off the school part of the plot, in which the narrator and his brother get their own back on the school bully and establish themselves as top of the social hierarchy.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “FROZEN STIFF”

“Frozen Stiff” is black humour, which revels in the death of animals, probably as a way of coping with the fact that animals (and people) do die. Animals especially die, and we eat them, or our pets eat them.

SHORTCOMING

The young narrator teams up with Old Jack Thaw, who is eccentric. The narrator therefore functions more as the viewpoint character. He’s helping Jack Thaw who can’t read, but nonetheless has a creepy hobby of freezing dead animals and arranging the bodies in alphabetical order according to species.

If you think about this too hard, why on earth would parents let their son hang out with a guy like this? This is the 1980s. You could ask the same of Marty McFly.

DESIRE

In a separate storyline, Jingle Bells is a cow locked up in inhumane conditions. The narrator feels like he has to save her.

OPPONENT

The man who locks up the cow is called Gravel. Because this is a Paul Jennings story, you will already know that Gravel will get his punishment.

PLAN

The narrator will pull the cow shed apart to let in some sunlight. Gravel appears and Jennings inserts a ticking clock — Jingle Bells is destined for the knackery.

BIG STRUGGLE

In a lengthy madcap scene, which I find distasteful for the female sexualisation of the cow in the train, the young ‘knight’ escapes with the saved ‘princess’ (my words, but this is a spin on that type of tale). The cow craps all over a lady on the train, because that’s how writers punish unlikeable women and girls in stories — by making them dirty.

The cow runs through central Melbourne and the juxtaposition of ‘country’ in the ‘city’ is the source of the humour. The picture book A Particular Cow by Mem Fox tells me that a cow running amok is an especially funny gag. False teeth, cows and — historically — bananas, these all seem to have inherent comic value.

In this big struggle, Jingle Bells ends up dead. Then there is a confrontation with Gravel, who wants the body to sell for pet food.

ANAGNORISIS

But when Jack and the narrator find a peaceful, countryside resting place for Jingle Bells, Paul Jennings reveals that the cow isn’t dead at all. While they slept, the ice melted and she walked off.

Jack also reveals that the water he used to thaw Jingle Bells was ‘different’ (magic). He was saving the magic water to bring someone special back to life.

Honestly, this feels like a bit of a hack.

NEW SITUATION

Finally, it is revealed that Gravel has become frozen. But they won’t bring him back to life. Being part of Old Jack Thaw’s collection is his punishment.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “UFD”

In “UFD”, a play on “UFO”, a trickster boy cracks on he’s seen a flying dog. Then he makes that happen. This is a classic fairytale structure.

SHORTCOMING

A boy narrator is in trouble for calling the police about an ‘unidentified flying dog’.

DESIRE

He wants to prove there really is a flying dog. The stakes are raised when he must prove it (and get $1000) or do the dishes every night for three years.

OPPONENT

The father and the air force guy who don’t believe the boy.

Then, the symbolically named dog who rips holes in pants.

PLAN

In a Paul Jennings story the next step isn’t necessarily an obvious step in the direction of fulfilling the main character’s desire. So it is here. The father suggests they go out and get ice cream. This seems kind of random, but Paul Jennings will turn this outing into an opportunity for the boy to vindicate himself (or whatever).

BIG STRUGGLE

After getting rear-ended at the railway boom gate, father and son meet Mrs Jensen and her mean bull terrier, Ripper. Mrs Jensen can be the witness to the accident. There is also another (hugely coincidental incident) in which the father rams the back of a mean trucker. So they do need Mrs Jensen as witness testimony.

The boy acts as mediator and approaches Mrs Jensen for this role. She ties her dog to the boom gate.

ANAGNORISIS

The set-up leads to a comic payoff in a more classic comedy structure — the boom gate goes up and flings the dog in the air.

NEW SITUATION

The boy now has $1000 dollars because he has proven the existence of a flying dog.

It is never revealed to us why he called the authorities about a UFD in the first place, which I consider a huge hole in the story. I believe Hitchcock would call this a refrigerator moment. I’m not meant to be thinking about this. I’m meant to be just chuckling at the vision of a mean dog flying through the air and ending up in a swimming pool.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “CRACKING UP”

“Cracking Up” is an interesting set of symbols which are related in a Word Association kind of way but which never link in any coherent manner: The maidenhair fern links to the tickling of the ghost which links to the teacher’s wig. This symbol web creates a set of comical connections.

SHORTCOMING

Russell Dimsey is picked by the designated teacher’s pet to take home the mean teacher’s maiden hair plant. He doesn’t want this.

DESIRE

Russell wants to avoid being responsible for Mr Snapper’s precious maiden hair fern.

OPPONENT

Mr Snapper. I can’t understand why Mr Snapper would entrust care of his precious plant to students he teaches, but I don’t think Paul Jennings worries about lampshading things like that. The nasty characters in his work are nasty AND illogical.

Lucy Watkins (though it creeps me out that a male teacher has ‘chosen’ a girl in this way). My mind goes off the page.

Lucy waits for Russell outside his new house specifically to tell him that the place is haunted.

The ghost, Samuel. Paul Jennings is smart by writing the following sentences:

I now know that you can only see ghosts if they want you to see them. He wanted me to see him. But not Mum.

That tells us two things: Something Russell has realised and something about the opponent’s desire. (Interesting opponents need their own desire lines.)

PLAN

Russell has no choice but to go to school and admit to Snapper that Sad Samuel has broken the pot. (Well, I suppose he could have chosen to lie, but Russell chooses truth.)

BIG STRUGGLE

This story, written in parts, contains a sequence of big struggles rather than a single big one.

The Battle begins when Snapper grabs Russell by the shirt front.

He wags school and ends up laughing a funeral when Sad Samuel starts tickling him.

There’s a showdown between Russell and his mother.

Finally he is reprimanded and shamed in front of a large audience (assembly). Writers often place characters in front of many people if they want to emphasise the significance of a speech or the climax of a big struggle. We see it also in Pixar’s Brave, in Big Love, with the middle wife giving a speech from the rooftop, in Tootsie. Once you start noticing it, you see it everywhere.

ANAGNORISIS

This is a story in which the main character has worked something out earlier. Eventually the reader works it out, too.

Russell has discovered that Snapper’s smile has been taken. If he gives it back, he’ll have a nice teacher again.

NEW SITUATION

Snapper is now known as Smiley.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “GREENSLEEVES”

Greensleeves is a popular piece of classical music and I’ve wondered myself why it is called Greensleeves. Nobody knows. Paul Jennings must have wondered, too, and he uses it to gross-out effect in this short story. This is one of the more gross stories of his oeuvre and I had a hard time getting through it.

This story is probably inspired by the real life incident in which a 45-foot sperm whale washed up on the beach in Florence, Oregon on 9 November 1970. The council decided to blow it up. To save you from looking it up, the story ends in disaster.

SHORTCOMING

Father and son are dual main characters, and complete underdogs. They have no money, live in a caravan (what Americans might call a ‘trailer’ or a ‘mobile home’). They therefore need to earn money in any way they can.

The son is more of an underdog than the father because he has to do as his father tells him, without any choice.

DESIRE

Father and son want $5000, which is enough for a deposit for a house. (Oh, those were the days.)

OPPONENT

The mayor is the father’s equivalent opponent; the mayor’s son is our main character’s same-age opponent. Mayor and son are power hungry. They go back on their word. They blame others for their own mistakes.

PLAN

Father and son will remove the dead whale from the nearby beach, which is decomposing and stinking up the entire town of Port Niranda. Nobody has been able to remove it, but the father has a plan and it involves the son getting inside the whale to place dynamite inside it. He’ll wear a gas mask so he can stand it.

Unfortunately this plan explodes, badly, literally. The mayor’s son has tampered with the dynamite and bits of whale blow all over the town. It will cost $5000 to clean up, so they don’t get their reward.

Father and son do good by helping to clean up the town. As in a fairytale, they are rewarded by ‘the gods’ when the son discovers a lump of ambergris has landed on a pillow. Paul Jennings uses the appearance of a ‘little man’ who is after just this product, and will pay not $5000 but $10000. Unfortunately, Nick Steal (who ‘doesn’t steal’) takes it and throws it around like a ball.

The stakes are raised when the father confronts the mayor again about stolen ambergris. “We search the room, and if we don’t find anything we leave Port Niranda tomorrow.”

BIG STRUGGLE

The action scene where the whale blows up is a man versus nature type big struggle. The boy loses his precious watch. (Watches were expensive back in the 1980s.) As for the interpersonal big struggles:

First Battle: Father and son confront the mayor saying it was his boy’s fault but mayor does not believe this.

Second Battle: The confrontation in Nick Steal’s room.

ANAGNORISIS

Paul Jennings does not mind coincidence. The degree of coincidence is itself comical.

As they all stand in Nick Steal’s room, Greensleeves starts playing. This is the tune that plays on the missing watch. Nick has put it in a trapdoor under a rug in his room. The ambergris just happens to have the missing watch embedded in it. So Nick Steal’s cover is blown because of the tune.

NEW SITUATION

Father and son are richly rewarded. They don’t have to leave town and I imagine they used this money to buy a better house.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “MOUSECHAP”

“Mousechap” is a body swap story. Paul Jennings has written a few of these. In one of his Gizmo novellas a boy accidentally swaps bodies with a dog. In this case, an uncle swaps bodies with a mouse. It’s up to the boy to save his uncle from a domestic abuse situation.

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

Dung beetles a.k.a. scarab beetles have been associated with reincarnation for a long time, especially in places like Egypt. It’s thought that being a shit roller is the worst thing you could possibly be, but that doesn’t take into account the fact that dung beetles seem to enjoy it, because they are dung beetles… If you’ve ever seen dung beetles at work, they are fascinating creatures. And they seem quite happy to me.

Australia imported farm animals long before it successfully imported dung beetles (though they did try, as early as 1900). The Australian Dung Beetle Project was happening big time as Jennings conceived this story. I can tell you that around here, where we live, years with good dung beetle activity mean far fewer flies. Dung beetles mean I can go for a walk without a net over my hat in summer. So dung beetles are my favourite animal.

SHORTCOMING

Julian doesn’t have any choice, but each year he is sent to holiday at his Uncle Sid and Aunt Scrotch’s house. But Aunt Scrotch doesn’t even like him.

He is afraid of the dark, or of the eyes which shine at him through the darkness of the bedroom.

Julian’s dung beetle is set up as a Chehov’s gun. He puts it into a matchbox in his pocket.

DESIRE

When Julian works out that there’s cheese everywhere around the house, he wants to find out why. (Jennings introduces a mystery.)

The reader will make the connection that cheese attracts mice (even though real mice prefer other foodstuffs — mice and cheese are culturally connected). Mice prefer sweet foods, grains and especially peanut butter.

OPPONENT/MYSTERY

Just by the name we know Aunt Scrotch is an opponent, but Paul Jennings is very clear about it: We are told she doesn’t like boys. Yet Julian wants to take a dung beetle with him to stay at her house for the holidays. So we have the classic crotchety aunt type against the rough-and-tumble, innocently dirty boy type.

It is gradually revealed by the narrator that Uncle Sid is not around. Something has happened to him. The reader probably catches on — after the mouse walks on two legs and prays — that Uncle Sid has turned into a mouse. In chapter two we see Uncle Sid locked up as prisoner, and behaving like a mouse.

PLAN

Julian sets Uncle Sid free but this is a mistake because Aunt Scrotch has a cat.

After the first revelation Julian plans to save his uncle who is trapped in a mouse’s body. ‘Suddenly I knew what to do’. Julian puts his uncle in his pocket, and I’m remembering there’s a dung beetle also in there.

BIG STRUGGLE

There’s a chase scene around the house, which involves a near miss with a mouse trap.

The second Battle is where Aunt Scrotch tries to regain control of the body swap machine.

The third and final Battle involves Aunt Scrotch turning into a dung beetle.

ANAGNORISIS

The first revelation (from a ripped diary page) is that the uncle has been body swapped because the mouse-trap electric fence switches brains over if two creatures touch the wire at the same time.

Julian is much slower to catch on that the reader. But in case the reader hasn’t picked it up, we are told exactly what happened after this revelation.

NEW SITUATION

Uncle Sid is back to his normal human self and Aunt Scrotch has been turned into a dung beetle as punishment, in this Buddhism inspired tale.

Julian keeps Aunt Scrotch in his pocket but his cruelty is lesser — he gives it as many chocolate freckles as it wants (Aunt Scrotch’s favourite food).

STORY STRUCTURE OF “SPAGHETTI PIG-OUT”

Certain items are inherently comic. Marina Warner has written at length about the comedy value of bananas, for instance. And for kids, spaghetti is another funny item because it looks like worms. Pigs, at least in the West, are also inherently funny. Our idea of pigs (stupid and dirty) is quite different from how pigs actually are (intelligent and clean). Paul Jennings makes the most of spaghetti and pigs in this gross-out short story, though ‘pig’ only appears in the title. The character of Guts is therefore compared to a pig.

SHORTCOMING

Paul Jennings deftly paints a picture of how bullying works in the opening of “Spaghetti Pig-Out” by describing how certain individuals are chosen to be the designated outcast. People who talk to an outcast lose social status themselves. This is a more nuanced picture of bullying than most of his stories offer. The character of Shaun, introduced later, is also realistic: Neither a friend nor a foe — simply too scared to stand up against the established hierarchy.

The narrator is the designated outcast in this milieu. This is possibly because he is poor, though the direct link is never made.

Matthew has a cat called Bad Smell. She farts. If you’ve read a lot of Paul Jennings you’ll know by now that this will come in handy later: The farting cat is the Chekhov’s Gun.

See also: Walter The Farting Dog (a New Zealand picture book).

DESIRE

The narrator wants to avoid being targeted by Guts Garvey and also wants a friend or two of his own.

When it is revealed that the cat has been turned into a remote controlled cat, Matthew wants to learn how to use her. (This trope is also used in Wellington Paranormal Series 1, Episode 6, which concludes with the police officers realising the zombified victims are remote controlled.)

OPPONENT

Guts Garvey — a ‘real mean kid’.

PLAN

Matthew’s plan aligns with his desire — he discovers how the remote control works by using it, in typical kid fashion (playing around with it).

When he learns that he can control insects, I’m reminded of a scene out of a completely different story — Eye In The Sky — a war thriller film starring Helen Mirren and various others. (One of the most suspenseful films I’ve seen lately.) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zWmEZAl4sxc

Matthew continues in carnivalesque fashion, playing rather than planning. He discovers the remote control works on people — first on his father, next on strangers. To keep reader empathy with Matthew, Matthew discovers this by accident.

BIG STRUGGLE

When the bully and his sidekick get a hold of the magical remote control, Matthew becomes victim of it.

Adult readers might remember from the 1980s and 90s that VCRs only pause for a few minutes, to avoid pixel burnout, and this functionality saves Matthew from being paused permanently. So, Matthew is still not planning his way out of this predicament — he is a hapless character who responds to crises in the moment. He is a low-mimetic hero (by Northrop Frye’s classification).

Paul Jennings must have realised that this to-and-fro with the remote control alone doesn’t make for a big enough climax, so he introduces a spaghetti-eating competition in part 7.

Circumstances out of his own control lead Matthew to regain control of the magic remote. And because Matthew doesn’t ‘plan’ — he ‘reacts’, Paul Jennings ensures he can’t be held responsible for the bully character eating his own vomit. Because that would be mean, right? That would make him seem vindictive.

Yet the reader is fully encouraged to delight in this punishment.

ANAGNORISIS

The reader realises that Matthew will no longer be at the very bottom of the social hierarchy because something really gross just happened to someone else.

NEW SITUATION

Guts Garvey is not unpopular and Matthew now has a lot of friends. In another (more didactic) story “The Busker”, Paul Jennings delivers a lecture about how you can’t buy friendship or romance.

But when it suits the story you can, and according to “Spaghetti Pig-out” you can buy friends with a magical device.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “KNOW ALL”

“Know All” stars a girl, because this is a take on the Greek tale of “Pandora’s Box”. In the myth, Pandora is created like a modern sex doll as the perfect specimen of womanhood and treated as a chattel. But there is one thing wrong with Pandora — she is too curious for her own good. The next part of the myth is like something out of a Jennings story — a massive stink comes out when she opens it. This stands for wickedness and evil. By my take, she finally realised she’s nothing more than a chattel and that misogyny exists. She’s now a woke feminist, and in this situation, this is a terrible realisation. But then she releases ‘hope’ from the box — the one good thing Zeus put inside it. The idea is that “sometimes you’re better off not knowing”. In modern speak, the power of positive thinking allows Pandora to exist within a misogynistic system of power.

What is Paul Jennings going to do with his Pandora character in “Know All?” Will he punish the girl main character for being a Know All? Or will her girly knowledge help her with a problem?

tl;dr: Kate is rewarded for her intellectual capacity, and I’m sure this story will be coded as feminist by many.

This is an outdated form of feminism, however, in which girls are viewpoint characters for the fun exploits of men and boys. The girls don’t undergo a character arc because they are already mature and sensible at the beginning of the story. This means Kate is not the main character. She doesn’t get a story of her own.

Do the boys in Paul Jennings stories get character arcs? Not exactly. These are comic stock characters. But they often rise in the social hierarchy, which is a Jennings stand-in for ‘character arc’. Kate does rise in the estimation of her own father, within the realm of the family rather than the realm of the outside world.

SHORTCOMING

Matthew is Kate’s brother, because as everyone knows, boys won’t read stories about girls. There needs to be an ensemble cast so boys can relate. (Insert irony punctuation.)

Matthew accuses Kate of being a Know All when Kate doesn’t want to open the box they find on the beach as buried treasure. We already know from the first sentence that opening the box was bad.

Kate is also accused of being a sad sack. Bear in mind, this is first person narration from Kate. She is mostly the viewpoint character and aligns with the audience, who shares her ‘intuition’ that the costumes inside the box are bad. The characters who get them all into trouble are the father and son, who don’t seem to possess intuition. The blunder forth and have fun.

DESIRE

Kate wants her family to put the costumes back in the box.

OPPONENT

They put the clothes on the scarecrow, which gives human form to the evil that comes out of the box. The scarecrow looks like superman, which is how most Greek gods are depicted (well, more like He-man actually).

PLAN

The father has a plan in which he decides to dress the Scarecrow in the clothes. But after that, the magic itself determines what happens.

BIG STRUGGLE

Most of this story is a harlequinesque caper as the clothes make its wearers perform like clowns.

The father accuses Kate of being a Know All. He doesn’t believe the clothes are magic. In an antifeminist move to keep her in check, he makes her cook tea for them both as punishment.

The life and death battle happens in video game fashion, atop a cliff with perilous holes in the ground. It’s a real action scene.

ANAGNORISIS

For no apparent reason, Kate is sure “there’s help in the box”. This is in line with the Greek myth. Why the hell does Pandora open that box a second time? No reason given. That’s how Greek mythology works. It’s impossible to work out from the Ancient Greeks why Pandora opened the box, whether she knew what was inside or anything else. It’s up to individual storytellers to paste motivation onto Pandora, in the rare cases she is afforded autonomy at all. In the Greek myth, ‘hope’ comes out last, so that is definitely the right thing to do. Perhaps Kate is familiar with the Greek myth.

Ultimately, Kate saves the day.

It is revealed that Kate knows exactly what to do because she put on the fortune teller’s costume.

NEW SITUATION

This twist at the end lampshades the fact that Kate has no reason to know all this stuff. It kind of subverts the Female Maturity Formula, but not really, because she was the designated mature female even before she put on the costume.