Unbelievable is a short story collection by Australian author Paul Jennings, copyrighted 1986. These are tall tales for eight-year-olds. Australia has a long history of tall tales, and Jennings very successfully adapted the techniques for a child audience. The 1980s was the decade of the irreverent male children’s author. Roald Dahl was the stand-out giant in this field, after starting out writing stories for adults. These days we have David Walliams and various other male authors. This genre of story continues to be a masculine domain, even though children’s literature is an industry full of women. This is carried over in Jennings’ stories for children.

In 1986 I was 8 years old, so the perfect age for Paul Jennings. When I look back on the creative writing myself around this age, they were very Paul Jennings-esque — usually written in the present tense, first person narrative, with a mischievous Every Boy as the main character, navigating his way through a perplexing suburban life, which would be boring and irritating if it weren’t for regular fantasy interruptions. So it’s very strange that I have no recollection of reading the work of Paul Jennings. Either I read them as a child and forgot that I did, or these stories were simply typical of the era. Roald Dahl is similar in many ways, and I certainly read Dahl’s entire oeuvre, numerous times over.

There are just nine short stories in the Unbelievable collection, which makes for a short book. ‘Reluctant’ readers could therefore enjoy the achievement of finishing an entire book without ploughing through a massive word count. (‘Reluctant’ often describes kids who haven’t yet learned to read fluently, which means reading itself is a lot of work. These kids are usually really up for a good story, if it’s accessible to them.)

Format

According to the Accelerated Reader website, another book in the Jennings’ ‘Un’ series has 32,000 words.

With about 9 stories to each collection, each story averages 3,555 words. That’s across 110 pages. In reality, the stories vary in length between about 1500 words to almost 6000.

These stories are not illustrated, which is slightly unusual for stories aimed at the emergent reader.

PINK BOW TIE

A boy gets his hands on a machine which allows you to alter your age.

SHORTCOMING

The main characters in Paul Jennings stories are the Every Boy. This boy is addressed as a ‘lad’ on the first page.

Because he is an Every Boy, we don’t know his specific psychological shortcomings and needs. We only know he is stuck in an external problematic situation. His problem is that he’s at a new school and has already found himself sitting outside the principal’s office.

Like all children everywhere, this Every Boy is lacking in autonomy and power, at the mercy of the adults around him.

But at the start of the second section, Jennings does give this particular Every Boy his own psychological shortcoming:

I am a very nervous person. Very sensitive. I get scared easily. I am scared of the dark. I am scared of ghost stories. I am even scared of the Cookie Monster on Sesame Street.

DESIRE

Jennings gives the boy a romantic desire, which turns out to be necessary to the plot.

Notice that the female characters in the stories are female archetypes: In this particular story we have the young sex object and her inverse in many ways, the horny old lady (who has the hots for John McEnroe). Was McEnroe a sex symbol of the era? I don’t remember, but I suspect Jennings chose him for the minor comic value.

Presumably, this boy also has the desire to get out of trouble. This is assumed.

OPPONENT

The reader relates to the boy because the boy makes a social faux pax, taking the piss out of the principal when he doesn’t have the information that this is the principal. (That’s why Jennings had to make him the new boy.)

The boy’s opponent is henceforth the principal, ‘Old Splodge’, who gives him the strap. This story was written just before laws were passed outlawing corporal punishment in schools. I remember a few kids (boys) getting the strap — one for pushing another kid off the top of the adventure playground, and another for giving a girl the brown-eye as the first of the girls’ cohort of cross-country runners caught up to the tail end of the boys. (The boys ran first.) He had the option of either the strap or a week of rubbish duty, so he chose the higher prestige option, after his mother gave the go-ahead.

This was in Year 8. The same boy, that same year, went on to sexually assault my friend in the back of a car full of kids being driven home from a birthday party. Nobody believed the girl… I had been picked up from the party earlier by my own mother, who didn’t feel comfortable leaving me there — so she related to me many years later. Her intuitions were right, because the party was badly supervised, by parents who scared me.

But I digress. Suffice to say, corporal punishment never worked. What that boy needed was intensive psychological intervention.

Notice how Jennings makes full use of descriptive nick names. We’re not told why the principal is called Old Splodge, but the ‘Old’ part is important.

Jennings is also making use of another subconscious bias — the bias against people who transgress gender rules. We are supposed to dislike the principal for wearing a pink bow tie, emphasis on pink. Pink is for girls and unattractively effeminate men. How is this boy supposed to respect a principal who has the outward appearance of a girly boy? He’s not supposed to, and neither are we.

PLAN

The Every Boy in Paul Jennings tales tends to go along for the ride. Weird things happen, then more weird things happen and he finds himself out of his situation through sheer good luck, and sometimes a bit of cunning.

In this case, The Every Boy narrator happens to get into a train carriage with some very strange people. Turns out they have a machine that can increase and decrease their ages.

BIG STRUGGLE

It hasn’t been clear to me until I analyse the story for The Battle, but this is actually a story with two diegetic levels. There’s the Level 0 story of a boy who has been sent to the principal’s office, ostensibly for dying his hair blonde.

Then there’s the Level 1, metadiegetic story embedded in that, in which the Every Boy tells us about what happened on the train yesterday.

The Battle of the Level 0 story is the principal grilling him about dying his hair. Jennings has sectioned this off neatly by calling it Chapter 2.

The Battle of the Level 1 story is between a ‘principal stand-in’ — another, similar authority figure — the guy who checks tickets and, similarly, tries to make everyone follow the rules. And no one wants to follow them.

The authority figure on the train ‘runs off as fast as his legs can take him’, which could be a line straight out of a fairy tale. (Not the Grimm versions, which ended differently — but of various 20th century English retellings. I’m sure I have a retelling of Goldilocks which ends like that.)

Chapter 3 marks the return to the Level 0 story, happening in the principal’s office. The principal has heard the same story we’ve heard and exclaims, “What utter rubbish!”

This is basically a rule in children’s fiction, and even in adult fantasy — nobody believes the main character when they happen upon something amazing and, well, Unbelievable.

But here’s another rule: The main character will eventually be vindicated.

REVELATION

Sure enough the principal has his revelation, because he tries the Age Rager machine which can alter someone’s age.

It is revealed in the end that the principal has disappeared, and that the sexually attractive, 17-year-old school secretary has a new, 18-year-old boyfriend. In case we’re in any doubt about what happened, this new boyfriend wears a pink bow tie.

It’s not 100% clear that the narrator realises the boyfriend is the magically age-reduced principal, which is deliberate — connected these (very easy) dots makes the beginner reader feel smart — possibly smarter than the narrator.

Reading from this time in history, in the midst of a #metoo era, there is something supremely icky about this ‘twist’ ending. In a post hoc analysis of the situation, the seventeen-year-old girl — and she is a girl, not yet able to drink, gamble or vote — was employed — probably by the principal himself — to work closely with him, and he was sexually attracted to her all along. This is a man whose very job is work with… children.

How has Jennings achieved what feels like a ‘twist’ ending? I am rebelling against that word, for some reason, wanting to put it in rubber-glove quotation marks.

To put it in clearer terms, Jennings is using the trick of misdirection. He introduced the 17-year-old receptionist as if she’s a part of the landscape. At the beginning we think she’s a side-detail, similar to a pot-plant in the waiting room, but it’s only at the end we realise she’s the reason for the principal winding his age back. Jennings used a technique known as Chekhov’s gun, but instead of an object, he used a person.

Therein lies my problem with it, on the back of a long, long history of the sexual objectification of young women and predatory old men. For me, the ‘twist’ isn’t funny — it’s not even unexpected. It’s more of a disappointed groan.

There is usually an ironic or cynical tone to such [endings], as if they mean to say “Ha, fooled ya!” You are caught foolishly thinking that human beings are decent or that good does triumph over evil. A less sardonic version of a twist Return can be found in the work of writers like O. Henry, who sometimes used the twist to show the positive side of human nature, as in his short story “The Gift of the Magi”

The Writer’s Journey by Christopher Vogler

NEW SITUATION

So, the old principal is now the young boyfriend of the attractive 17-year-old girl, who is presumably either too stupid to realise who he is (despite the ostentatious pink bow tie) or too pressured by the hierarchy of the situation to resist his sexual advances.

Child readers don’t encode the narrative like that, of course, because all of this weirdness bubbles under the surface and is completely normalised. Normalisation is exactly the problem. Readers are not encouraged to question the girl’s autonomy in any of this. We assume that because ‘all the boys’ find Miss Newham sexually attractive that she feels the same way in return.

An older character in a young person’s body was roundly criticised as creepy and predatory when Stephenie Meyer used the trope in her Twilight series. An old man (Edward Cullen) stalks seventeen-year-old Bella Swan. The creepiness was mitigated for other readers because we saw Bella’s point of view, and knew she found him sexually attractive. Therefore we knew there was consent.

Consent is off the page in this story. Yet Paul Jennings appears to have gotten away with the device. Mainly, he was writing in an earlier era. Also, the storyline of the 17-year-old girl in “Pink Bowtie” is secondary — almost a MacGuffin, or so we’re led to believe. The viewpoint character is the boy. We worry about the emotional safety of the boy, with no thought to that of the girl. In contrast, the character of Bella Swan is the viewpoint character of Twilight, so some readers do worry about her.

ONE SHOT TOOTHPASTE

A dentist spins a tall tale for a boy who is nervous about getting a filling. The story is the origin story of the massive tooth used as signage outside the window. This story has a more successful twist at the end.

“One Shot Toothpaste” is written in third-person. It seems Jennings has a natural preference for writing in first person, unless there’s a storytelling reason for writing in third. The reason here is because at the end, the young viewpoint character is not in the picture, because another child turns up and the repeating pattern continues.

Having recently visited the dentist myself, an early detail struck me as wrong: After getting the numbing needle, you are not required to spit. But maybe you were required to spit in the 80s. I don’t remember. (Numbing needles are still huge. Not the needle itself, mind, but the receptacle on the end of it. A perennial source of terror.)

As in “Pink Bow Tie”, this story is a story within a story — the Level 0 story is the boy in the dentist’s chair. The Level 1, metadiegetic story is the dentist telling the boy about how he always wanted to be a dustman.

There’s a comic irony embedded in the MacGuffin of “One Shot Toothpaste” — a high prestige dentist longed for (and still admires) the lowest prestige job out there — cleaning up after other people, behind the scenes. (It’s a MacGuffin because this desire gives the young dentist a reason for looking through bins, but his desire abruptly changes when he realises there is animal cruelty going on.)

PROBLEM

The main character of the Level Zero story is Antonio. His problem is revealed in the first sentence: He needs a filling, and he’s scared of the numbing needle.

His psychological shortcoming is that he is terrified, shown by the comical description of his knocking knees.

The main character of the Level 1 story is the dentist as a child. The dentist doesn’t have a problem but he has a mystery to solve. (The ‘problem’ is that he can’t rest until he finds out why his neighbour seems to go through so much toothpaste.) Because this is a tale told by an older man to a boy, this can be interpreted as a tall tale — the sort of story a dentist might spin to keep the boy’s mind off his fear. (It’s a masculine genre.)

DESIRE

The dentist wants to solve the mystery of Mr Monty’s toothpaste tubes.

OPPONENT

Mr Monty is presented as the likely opponent. The young dentist is going to peer into his ramshackle house.

Sure enough, it is revealed that Mr Monty is holding animals captive, testing foul-tasting toothpaste out on them, hoping to come up with a recipe that will make his fortune. Mr Monty is a Eustace Bagge character (from Courage the Cowardly Dog.) He has no power in real life, and dreams of riches. Eustace Bagge sometimes comes up with outlandish schemes to this end. (They never work.)

A cursory look at the list of fictional characters named Monty confirms for me that this name has become associated with powerful but defeatable villains. Montgomery (Monty) Burns of The Simpsons springs first to mind.

PLAN

So, we’re clearly given the opponent’s plan. (Jennings has him talk to himself, like a mad scientist type.)

The young dentist ambushes Mr Monty.

BIG STRUGGLE

The Battle of the Level 0 story is the psychological big struggle as the boy gets his tooth filled, despite his own terror.

The Battle of the Level 1 story begins with section three, in which Mr Monty tries to capture the young dentist to try out his ‘one shot toothpaste’ on a boy. At the end of section three, the young dentist has ‘won’.

Section four is a comical description of a fantasy scene. The tooth grows and grows and overtakes Mr Monty, consuming him as it grows bigger. Mr Monty’s own invention has consumed him. This is a horror trope from way back.

Jennings is making use of another trick here, common to children’s stories in particular — he’s playing with our sense of scale. Children’s humour is augmented by making tiny things massive and massive things tiny. The image of a rotten tooth turning into the villain is in itself comical to a young audience. This is a comical image of irony: A meaningful gap between audience expectation and outcome.

Expectation: A small tooth is small and needs looking after by its ‘owner’

Outcome: The tooth is actually the boss.

The wrapper story of a boy being at the dentist is therefore masterful on a psychological level, because when you’re at the dentist, enduring terror and perhaps pain, you realise, perhaps for the first time since your last visit, that your teeth are more important — more powerful — than you thought. For the first time, you’re centring your tooth in your own narrative.

A shift in psychic valence is another classic feature of horror. The ordinary becomes the terror.

Jennings ends the horror scene with a comical Rube Goldberg type device:

- Kangaroo tries to escape

- Knocks over candle

- Curtain catches alight

- House burns down

REVELATION

The final section (Chapter 5) of this story ends with a genuine, satisfying twist and it is achieved like this:

The dentist reveals that a massive tooth signage outside, advertising his business, is the real fusty tooth from his tall tale. Take note: This would not have worked if Jennings hadn’t mentioned its existence on the first page. But we weren’t meant to make special note of it.

How does Jennings make sure we don’t make special note of it? By diverting our attention to the comically symbolic name written on the side: M.T. Bin. We are busy sniggering that M.T. Bin is pronounced ‘Empty Bin’.

That revelation belongs to the Level 1 story.

But there’s a second revelation which belongs to the Level 0 story: This has indeed been a tall tale invented wholly to keep the child’s mind off his filling. In a circular ending common also to fantasy picture books, another, similar story begins again, this time with a little girl. The dentist tells her that he, too, always wanted to be a ballerina when he was a boy. He launches into a tale and we the reader can only imagine what that might be.

NEW SITUATION

We extrapolate that the dentist spends all day spinning tall tales for his nervous patients.

But there’s always that little bit of doubt. Are any of them true? For all we know, the dentist wanted to be a dustman and then he also wanted to be a ballerina. This element of doubt is essential in providing that last ten percent of the frisson of delight in the twist ending.

THERE’S NO SUCH THING

A boy gets his grandfather out of a sanatorium by proving that he’s not imagining things — there really is a dragon down Donovan’s Drain.

This one is written in first person.

PROBLEM

Chris misses his grandfather, who has been locked up in a sanatorium. Although this is a modern 1980s setting, I do remember these really old-fashioned (and hugely damaging) institutions for the mentally ill population were closing down around this time. The example from my own home town was Sunnyside Hospital (formerly Sunnyside Lunatic Asylum), which didn’t fully close down until 1999, but which was roundly criticised from at least the 1980s onwards.

So it’s easy to forget that these places did exist in the 1980s. These days, the existence of a sanitarium as described in the story feels like a throwback to the 1960s, at least.

DESIRE

Chris wants to help his grandfather vindicate his own sanity by taking photographic evidence of a dragon that the grandfather has seen in a drain. I have a theory that Paul Jennings had just read Stephen King’s IT when he wrote this story. (IT was published in September of 1986.) Either that or monsters down drains were in the collective air.

OPPONENT

Normally in a story featuring a dragon, the dragon is the opponent. But in this story, the opponent is the authority figure at the sanatorium. Paul Jennings loves authority figures as opponents. Basically, he loves to exact revenge on characters who robotically do their jobs without letting their humanity shine through.

PLAN

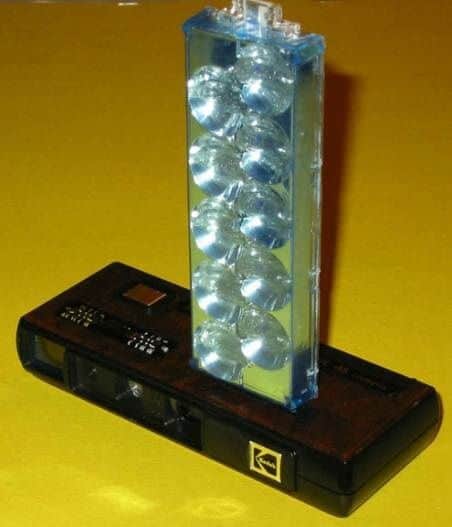

Chris visits the drain at midnight equipped with a flash camera (in those days cameras didn’t come with a flash — flashes were an add on, and I still remember the huge tower of little lights, which required a truckload of batteries to work), which was bigger by far than my father’s camera itself.

No word of a lie, it looked like this:

(ANTI-CLIMACTIC) BIG STRUGGLE

So Chris waits until midnight, because the dragon is only seen at midnight, and goes on this mythic journey into the underground. In more lofty stories, this journey into the underground would represent a journey into the main character’s psyche, symbolic of his deepest, darkest fears, but Jennings takes the structure of these serious stories and makes light of them. In fact, the journey itself feels like a necessary but not all that interesting sequence. (A young reader may differ.)

Jennings doesn’t linger down there — the anticlimax is that the dragon is asleep. Chris fails in his mission to collect photo evidence because of a calamity with the camera, but he does emerge from this fantasy world with a talisman — a red cube.

REVELATION

I have since looked up whether there is existing, well-known folklore about dragons and cube-shaped eggs, because the revelation is that Chris has come back to his grandfather with a dragon egg. (I wasn’t all that surprised — but I wasn’t supposed to be.)

Turns out the cube dragon egg is Jennings’ invention. He needed to invent his own folklore in order to surprise the reader with the revelation that he’s brought an egg back into the real world.

(REAL) BIG STRUGGLE

Because Jennings has given the reader an anticlimax with the dead dragon mum proving a non-opponent, now we have the real Battle scene, in which a dragon hatches and immediately attacks the horrible nurse keeping the grandfather prisoner.

This is a vengeful scene — wish fulfilment to exact punishment upon a nurse for refusing to believe something which — let’s face it — no properly skeptical reader would ever believe, either.

NEW SITUATION

We extrapolate that with the nurse out of the way, granddad will return to his home as a free and sane man.

The truth of the setting has won out. The child hero has saved the day.

INSIDE OUT

Gordon is scared by nothing, unlike his sissy sister. Until he comes face to face with a ghost who wants to pass his spooking exams by turning him inside out, like a sausage.

SHORTCOMING

Gordon believes there’s nothing that can scare him. His fearlessness is established in opposition to the scaredy-cat nature of his sister, who wants to watch Love Story when Gordon wants to watch a slasher horror.

We know, therefore, that Gordon is going to come face-to-face with something really scary and get his comeuppance. Part of the pleasure of this tale is in waiting for that to happen.

The problem with this set-up is that it relies upon a system of misogyny, and unwittingly supports it. Gordon is our viewpoint character and he believes Love Story (ie. thinking, feeling, emoting stories) is girly, and because anything girly is inferior, he wants nothing to do with it.

Although Gordon’s bravado comes tumbling down, there’s nothing within the story itself to subvert the notion that girly = inferior. And that is the problem with stories like this.

There’s nothing 1980s about this, by the way. Middle grade authors (especially male authors) are still using girly as inferior to undercut their male main characters, while failing to dismantle the underlying misogyny.

I don’t think they even realise it’s there.

DESIRE

Gordon wants to watch a slasher movie.

When this proves impossible, he sets out into the world in search of something scary. Jennings doesn’t go out of his way to give Gordon a plausible motive. Rather, Gordon is the archetypal fairytale brother who sets out into the world ‘to seek his fortune’. He’s a lad in search of something, anything, to disrupt the utter monotony of his ordinary life. And the reader accepts that in a young man.

Note: Readers don’t tend to accept this motive in anyone other than a young man.

Ostensibly, Gordon leaves the house to teach Mary a lesson — she’ll be scared alone in the house without him, as the parents aren’t back until early the following morning.

OPPONENT

Gordon’s initial opponent is his girly sister, who initially tries to persuade him against the slasher movie, then steals the video tape.

The central gag is that Gordon comes face to face with a variety of horror tropes, but doesn’t really draw a distinction between movies and reality, so he isn’t scared by any of these scary things. At this point I wonder how the gag will end. I think the only way this could possibly end is by showing Gordon to be scared of something run-of-the-mill — something ordinary kids would NOT be scared of. Anything other than irony would fail to finish it off… that I can see. Then again, Jennings might have advanced tricks.

PLAN

Gordon’s subconscious plan is to run into something spooky.

But it’s the fake-opponent who has the more thought-out plan: To pass his spooking exams by scaring a boy half to death. Gordon becomes the target in this comedy thriller. (But comedy thriller is a very hard genre mix, and I don’t consider this story one of Jennings’ best.)

BIG STRUGGLE

The punk tries to scare Gordon by sprinkling pink powder on a sausage, then on a watermelon, before instructing them to explode.

Next he sprinkles the pink powder onto Gordon, and we worry he, too, is going to explode like a sausage. In the nick of time, the examiner ghost drops to the floor in fright, I assume at the prospect of seeing Gordon with his innards on the outside.

Gordon also faints too, and I wonder if he has turned into an exploded sausage. Honestly, I don’t really get this bit. Is he meant to be an exploded sausage ghost now?

ANAGNORISIS

Turns out I was right — Paul Jennings really had no choice but to end this story the way he did — by depicting Gordon as scared of things that aren’t scary. Gordon is revealed to find The Great Muppet Caper really ‘creepy’.

In any case, Gordon walked home with his knees knocking. After this experience he is finally scared of things now.

NEW SITUATION

From now on he knows to be scared of certain things.

THE BUSKER

A boy wants money to take the designated Hot Girl at school out on a date. She has told him she’ll only go out with him if he takes her by taxi. His father won’t give him money, so he goes to the beach in search of The Mahogany Ship. If he finds this, he reasons, he can make lots of money. But at the beach, a stranger emerges from the shadows…

WEAKNESS/PROBLEM

A boy is attracted to a girl who will only go out with him if he can afford to take her out by taxi.

He doesn’t have the money.

What he is wrong about in the beginning: He thinks as long as he has the money he’ll secure Tania as his girlfriend.

DESIRE

He desires the girl, or the status that the girl will bring.

To get the girl, he needs money.

OPPONENT

The romantic opponent of the Level 0 story is Tania, described as an archetypal 1980s catch:

This wasn’t just any old date. This was a date with Tania. She was the best looking girl I had ever seen. She had long blonde hair, pearly teeth and a great figure. And she had class. Real class.

(White het men of Paul Jennings age overwhelmingly fetishise blonde women, having come of age in the Marilyn Monroe era.)

The boy narrator goes on to say:

She had already told me it was a taxi or nothing.

We don’t get to see Tania on the page, but my interpretation is that Tania does not want to go out with this boy. She wants to go out with Brad. Instead of risking backlash by turning him down flat, she has put the ridiculous condition of ‘only by taxi’ on her ‘yes’, knowing full well that he doesn’t have the money. Instead, he sees this as a challenge to overcome. The boy narrator sees it as a ‘yes’, because he hasn’t been told a direct and insistent ‘no’, and because he is not even listening for ‘no’.

This desire line is already creepy to me, then I notice something else.

Brad Bellamy is the guy Tania is really interested in, which is kind of prescient because Incels have since imbued their own meaning to the name ‘Brad’. A ‘Brad’ is a guy who supposedly gets all the attention from high status ‘Staceys’, while the low status men, involuntarily celibate, feel righteously aggrieved for missing out on sex they feel that they feel they are owed.

Why do they feel they are owed these ‘yes’s from Staceys, or Tanias? Because 1980s media told them that blonde girls with pearly teeth and great figures are their prize. I played a lot of arcade games on my Amstrad as a kid in the 1980s. The few times I clocked a game, it was a letdown to realise that the outro sequence often consisted of a pixellated but unmistakeable ‘Tania’ emerging from right of screen to plant a massive kiss on my — until this moment — genderless avatar. This phenomenon was critiqued brilliantly by Anita Sarkeesian back in 2013 in her Tropes vs. Women video series.

PLAN

Paul Jennings gives his main characters weird plans. There’s nothing sane that really leads this boy from

- Need ten bucks to

- Will go in search of long lost treasure on the beach

But that is the wacko nature of Paul Jennings stories and we accept that happily. There is the in-between step, in which the boy offers to mow the lawn for payment, and a funny anecdote backstory about how he’s not allowed to do that anymore after mowing over a whole row of plants. (I find this supremely irritating as a parent—it probably mildly funny to its young, target audience.)

Anyway, that’s why the father won’t just give the boy ten dollars. That’s why he goes in search of The Mahogany Ship. Non-Australian readers won’t necessarily know that The Mahogany Ship is thought to be a shipwreck buried under the sand on a beach in South West Victoria. There was much talk about this in the 1980s and 1990s because two writers documented all the reports. This explains why there’s no explanation in the story itself.

BIG STRUGGLE

Alongside this Level 0 story we’ve got the metadiegetic Level 1 story of the mysterious man on the beach who steps out of the shadows to tell a lengthy cautionary tale against trying to impress others by giving them money. The lesson is that the more you give, the more people take. And you can’t buy love anyway, no matter how much money you give someone.

This entire story has its own 7-step structure of course. The dog down the well reminds me of Silence of the Lambs, which was actually published 2 years AFTER this collection was copyrighted, so I guess people and little dogs in wells was in the collective narrative air.

The Battle of the story takes place within this metadiegetic story. In the end, the loyal little dog dies and teaches the busker narrator a lesson. It’s a real tearjerker—manipulatively so.

ANAGNORISIS

The plot reveal is that the busker is the star of the story. The misdirection (which probably works on a young audience) is that he was talking about himself in the third person.

The anagnorisis in the Level 1 story is that money doesn’t buy friends. Your friends simply are — as exemplified by the loyal little dog. As a message this doesn’t exactly work, because the little dog sacrificed all its own food and ultimately its own life to ‘buy’ the affection of the busker, but heigh ho.

As for the Level 0 story — the boy does not get the girl. He has his own epiphany prompted by the moral lesson: He does not even want a girl who requires an expensive mode of transport. She is suddenly disgusting to him. I’m sure Paul Jennings considered this a subversion of the trope that boys who behave ‘well’ always get ‘the girl’.

But it’s not a feminist subversion at all. The idea that boys deserve pretty girls instead gets an addendum: boys deserve pretty girls who are also nice. (And presumably self-sacrificing. No accident that the busker’s dog is small and female. Bear in mind the default gender for fictional dogs is male.)

The epiphany our boy narrator should have had: He should leave Tania the fuck alone, because Tania wants nothing to do with him in the first place.

NEW SITUATION

I stuffed the ten dollars into my pocket. Then I went round to Tania’s house and told her to go jump in the lake.

The reader is meant to feel some catharsis at this final sentence.

Here’s what remains in the story: The old chestnut that pretty girls tend to ask for too much from men who chase them. They use their high beauty status for monetary gain.

The boy still doesn’t realise that Tania was never interested in him in the first place. He literally went round to her house—her safe space—to insult her.

SOUPERMAN

“Souperman” is set in the city — the natural arena for a superhero tale. Paul Jennings takes the classic super hero (the classical god) and strips him of power until he is a low mimetic human (according to Northrop Frye’s classification). Any boy can be Souperman, so long as he drinks the soup.

SHORTCOMING

Robert is obsessed with Superman comics to the point where it’s affecting his school work. His angry father insists he dispose of all his Superman paraphernalia.

DESIRE

Robert wants to be a super hero.

OPPONENT

His opponent is his father, who makes him get rid of all his Superman stuff. This makes him even less like a superhero than he was before.

He meets Souperman, who at first proves to be a fake-ally, teaching Robert how he, too, can have superpowers.

PLAN

Robert does as Souperman suggests and eats ‘raw’ soup from a can (canned soup is never raw, but ‘raw’ does sound better in a tall story).

BIG STRUGGLE

On the way back up from the skip he encounters ‘Souperman’ who tells him that if he eats certain flavours of canned soup he’ll be able to perform specific feats attached to the flavours. He tries out the theory and fails, but is left with the problem of indigestion.

Next he gets himself into a further scrape by falling into the council skip, which is then picked up by the rubbish truck. He’s about to be crushed.

The maybe-fake Souperman does save the day, by rushing downstairs to tell the rubbish truck driver to stop the crusher.

ANAGNORISIS

Souperman saves the day using only human abilities (he falls from the window rather than flying), and tells the driver to stop (rather than making it stop with superhuman strength). We conclude he’s just a guy playing at being a superhero.

But the plot twist is that Robert has inadvertenly taken off with the can opener, which means Souperman couldn’t eat the soup purported to imbue him with temporary superpowers. Souperman insists that he can fly, but only after eating soup.

In short: The twist ending is achieved by persuading the reader something fantasy is actually mundane, then adding extra detail to make us revise that view — that the mundane could still be fantasy.

NEW SITUATION

The reader is left with an intriguing question — this Souperman guy could still be a real superhero.

Ergo: Any guy dressed in a superhero costume could, just possibly, be a real super hero.

This ending fits well inside a collection called Unbelievable.

THE GUM LEAF WAR

A boy on a train knows that the other passengers are staring at his nose. He launches into backstory about how he got his nose stuck between two swinging doors. Now it is 7cm long. He can’t cope with the teasing at school so his parents send him on a country retreat.

Click Go The Shears is an Australian bush ballad. Unfortunately the most popular versions you’ll find on YouTube are by Rolf Harris, and Rolf Harris has since been found guilty of 12 counts of sexual assault. This was all going on in the 1980s, when this story was written. He abused children.

Here’s a version not by Rolf Harris

And here’s what a gum leaf tune sounds like, if you’re a pro:

WEAKNESS/PROBLEM

The boy is left with a massive nose after an accident. His shortcoming is that he can’t lead a good life without fitting in, looks-wise.

DESIRE

He wants his regular nose back again. In the meantime, he wants to get out of school to avoid the bullying.

OPPONENT

The kids at school are the narrator’s initial opponents, for making his regular life a misery.

Grandfather McFuddy at the farm is going to be either an opponent or an ally to his grandson. But the neighbour, Foxy, is quickly established as McFuddy’s ally.

Like Hatfields and McCoys, these two old men are at each other’s throats. The young narrator works out what’s going on without too much trouble. He summarises it for the reader:

This was the weirdest thing I had ever come across. These two old men seemed to be able to give each other their illnesses and cure themselves at the same time. By blowing a gumleaf where the other person could hear it.

PLAN

The boy goes exploring around the farm. Children in fiction are obliged to explore any new environment. Coraline does the same thing. Incurious children don’t seem to exist in books.

BIG STRUGGLE

The tree goes up in flames.

Neither of the old men, temporarily made friends through working together to fight the flames, realised the old twisted gum might be in danger. Though the reader has already deduced this, they realise the gum they’ve been weaponising is now a burnt and twisted corpse. Except for one leaf, which falls to the ground.

The boy transfers his long nose to the two old men, settling the rivalry between them by giving them both the same affliction, and also solving his own problem.

REVELATION

The old men have the revelation that once both of them are afflicted by the same thing, they are no longer automatic rivals.

NEW SITUATION

The ranger on the train on the way home notes that gum trees tend to spring back to life after bush fire. This produces more leaves. The rivalry is likely to start up again. This sets up expectation of a repeating story.

BIRDSCRAP

Birdscrap has a strong gross-out element. 15-year-old twins Gemma and Tracy are at the beach. They end up covered in seagull crap. But why? This one’s a ghost story.

Consider this the kiddie version of Daphne du Maurier’s The Birds, later adapted for film by Hitchcock.

This is the story in the book starring girl(s). It feels tokenistic. I’m a little creeped out by the gendering of it, but in order to understand why, you have to know some context: In middle grade fiction it’s always ‘funnier’ when girls get covered in dirt, or crap. The girlier they are, the more satisfying it’s meant to be. Usually it’s revenge for being too girly, but includes an easily milkable slapstick comedy element. The characters in “Birdscrap” could easily have been boys — indeed, Jennings’ default character is boy. Jennings chose to cover girls in shit, for a reason. A completely subconscious reason, I’d wager.

PROBLEM

“Birdscrap” is a Holy Grail type of quest to find hidden treasure, described only as ‘Dad’s rubies’. The problem is, they don’t know where to find them.

DESIRE

The twins want to find the rubies so they can ‘sell them for a lot of money, fix up Seagull Shack and give Grandma a bit of cash as well’. Because we’ve got two twin sisters talking to each other, this is revealed in dialogue, as they argue about whether this is an idea worth pursuing.

In general, Holy Grail plots have something really specific the character wants — probably something they can hold in their hand. But deep down the outer desire is different e.g. to be accepted, to make a friend, to get past a break up.

But the hi-lo fiction of Paul Jennings doesn’t have that kind of complexity. The rubies don’t stand metaphorically for any deep desire. These girls are cardboard cut outs — they could be anyone. The interest factor for young readers derives from:

- the gross-out spectacle of girls covered in poo, and a shack surrounded in poo

- the intrigue of an invisible bird

- the intrigue of a ghost who has come back for revenge

- the reveals

OPPONENT

An invisible seagull craps on the girls. Soon they’re bombarded, and absolutely covered in crap.

PLAN

The girls take refuge in Seagull Shack. One of them checks the inside of the bird for the missing rubies.

They put the creepy stuffed seagull on the windowsill.

BIG STRUGGLE

A ‘lonely darkness’ settles upon the shack and the night is one long psychological big struggle for the girls as the stuffed seagull stares at them from the windowsill where they released it back into the wild.

Once again, Jennings is making use of an exaggerated scene — most of us have the experience of being crapped on by a bird. This is that, taken to its extreme.

In the morning they realise the shack is surrounded by a huge volume of bird poo. No one knows they’re in the shack, so the twins consider themselves doomed.

ANAGNORISIS

They conclude the stuffed seagull is the body of the transparent seagull bombarding them, then plan to fix the problem by giving the ghost gull its body back.

The big reveal is that the eyes of the stuffed seagull are the rubies. It’s pretty unbelievable, on a narrative level, that the girls would rip the entire stuffing out of this bird and check it for rubies, yet wholly fail to notice that the creepy eyes staring at them all night are… rubies. This is the wrong kind of ‘Unbelievable’.

The ‘twist’ feeling in the end comes from the revelation that the bird is an ally opponent, not an outright villain. In its own way, the ghost seagull has ensured the girls would find the rubies. The ghost gull has a strong sense of reciprocity.

NEW SITUATION

The girls are left with the rubies and henceforth they’re rich. They will probably do as they discussed: fix up the shack and live there together.

The ghost gull disappears (presumably forever) with its band of shitting marauders.

SNOOKLE

This is the only story in this collection which made me LOL. Remember milk deliveries? They stopped sometime in the 80s, so I doubt young readers would even know what that’s about.

PROBLEM

A creature named Snookle arrives in the milk bottle. This creature wants to do everything for the child narrator, including picking his nose for him.

DESIRE

The narrator wants to continue doing things for himself, without being treated like a helpless baby.

OPPONENT

Snookle.

PLAN

The narrator tries to resist.

BIG STRUGGLE

There’s a big struggle for control.

I went back to the kitchen for my breakfast. Snookle beat me to the spoon.

ANAGNORISIS

Off-the-page, the narrator realises that there are people in life who do need this kind of personal care. So he rehomes Snookle with the elderly woman next door, who can barely go outside to pick up her milk bottles.

NEW SITUATION

The old lady now has someone to help her stay in her home. The lawns are mowed and she seems very happy. And the narrator is glad to be rid of Snookle.