Considering how similar cats look in reality, breeding and colour differences aside, it’s surprising how illustrators come up with so many ways of depicting cats in art. Like any other fashion, cat faces have also changed according to era, even though the faces of actual cats have remained… the exact same.

How Humans Created Cats: Following the invention of agriculture, one thing led to another, and ta da! the world’s most popular pet, from The Atlantic

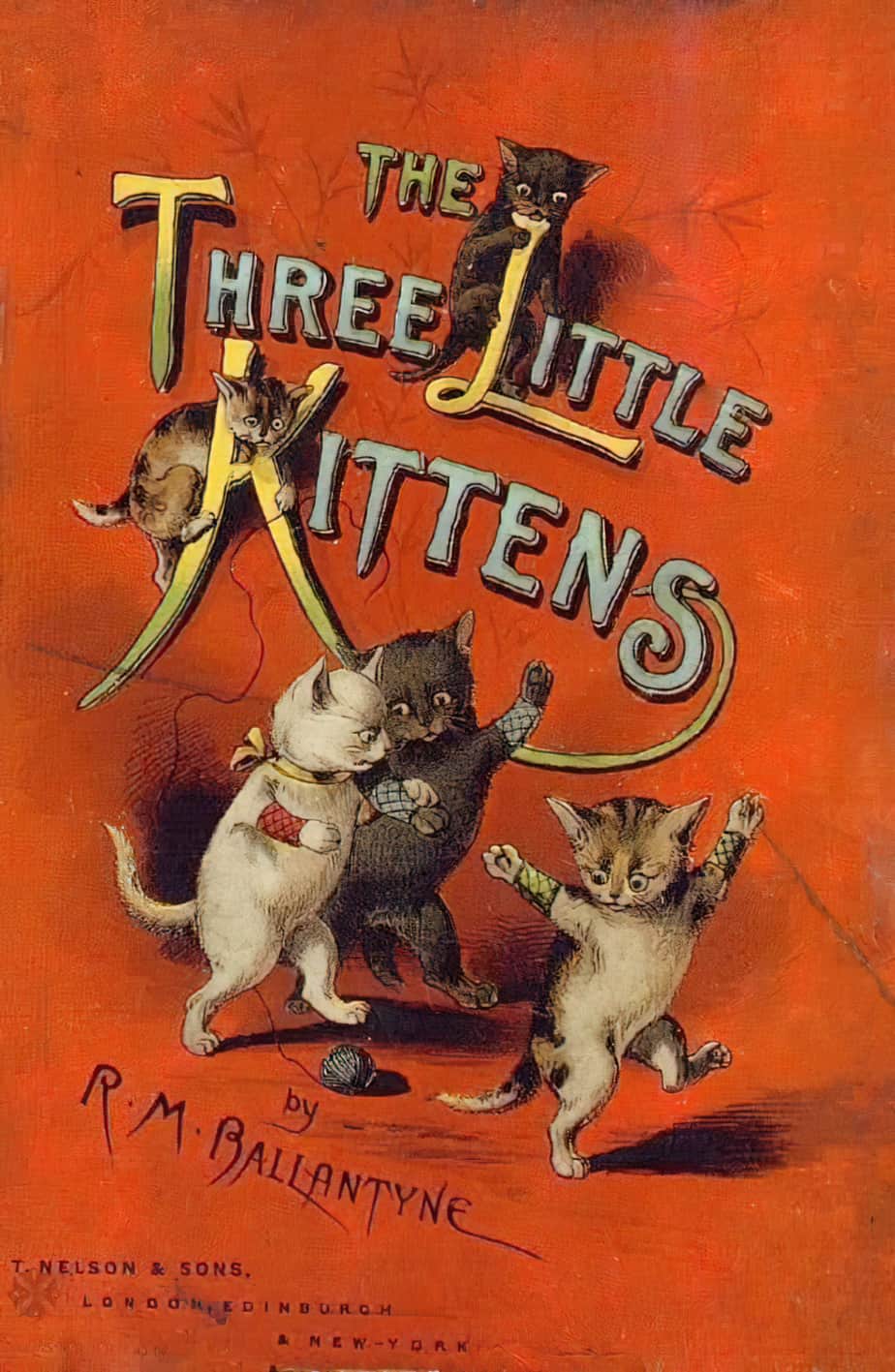

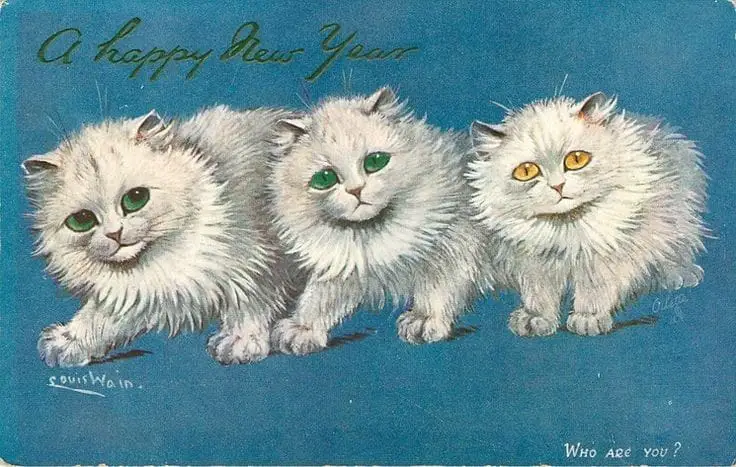

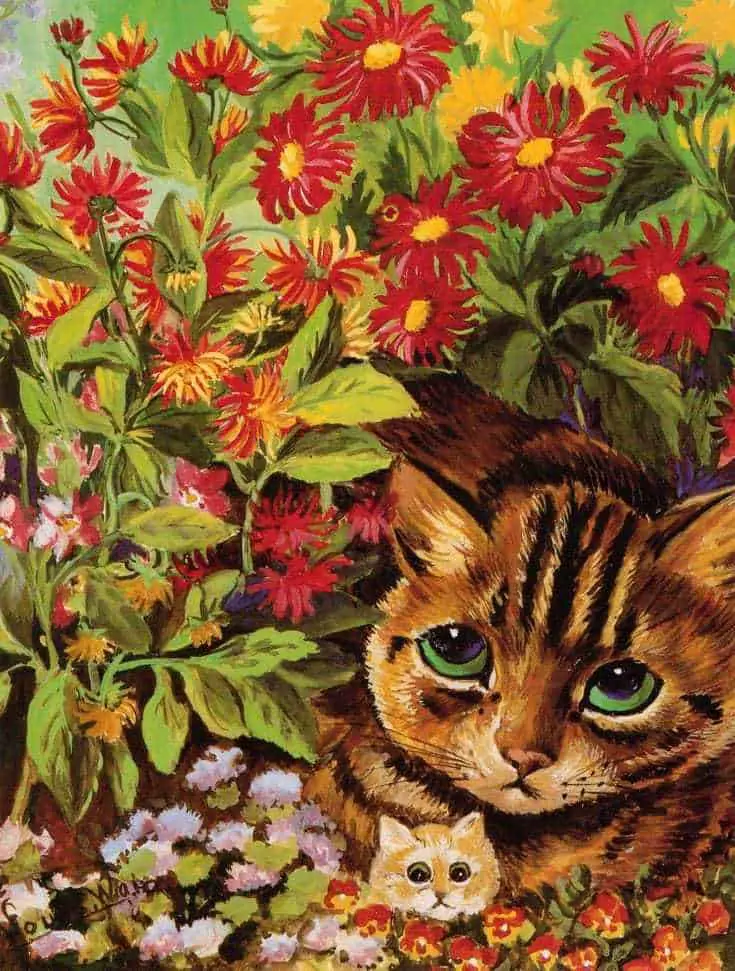

Cats can be rendered as very cute, though the concept of cute itself changes over time. I don’t find the big-eyed cats of Louis Wain appealing, for instance.

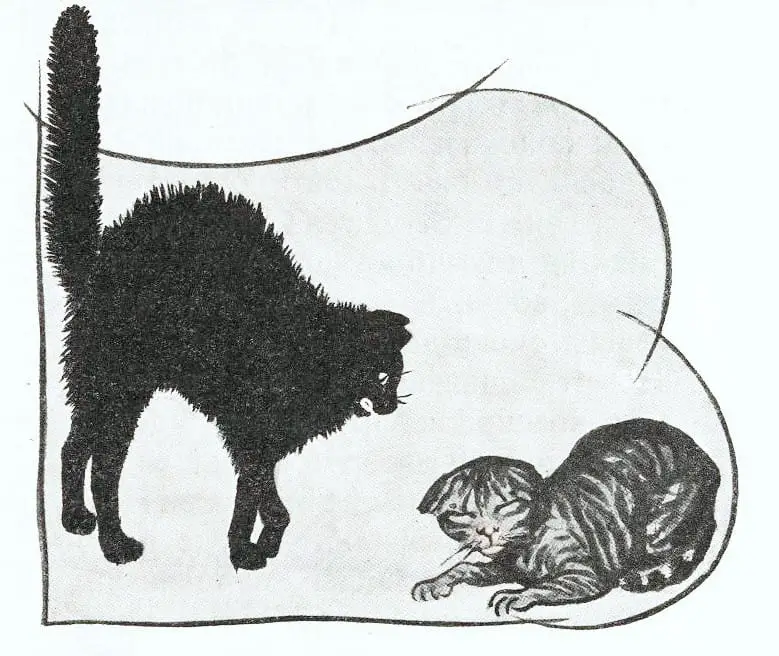

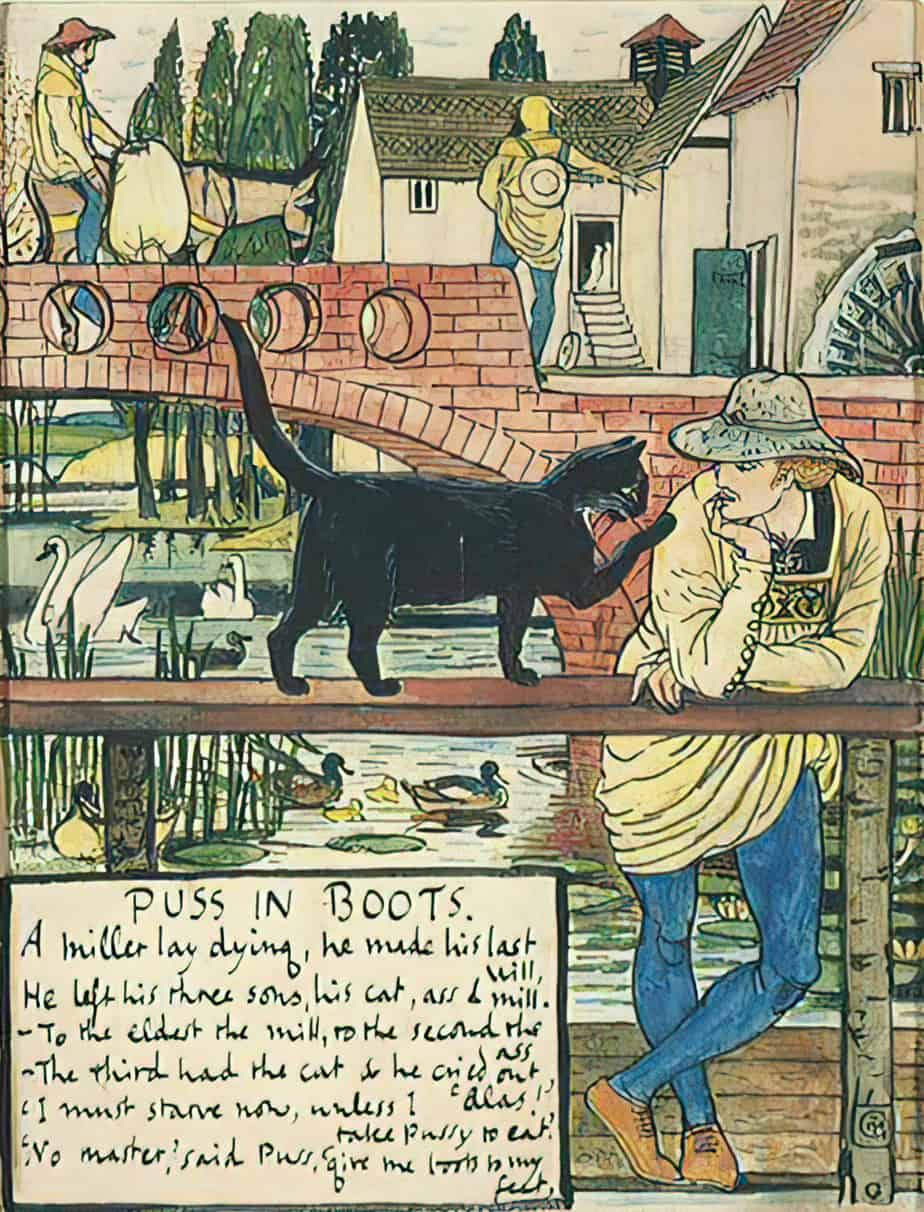

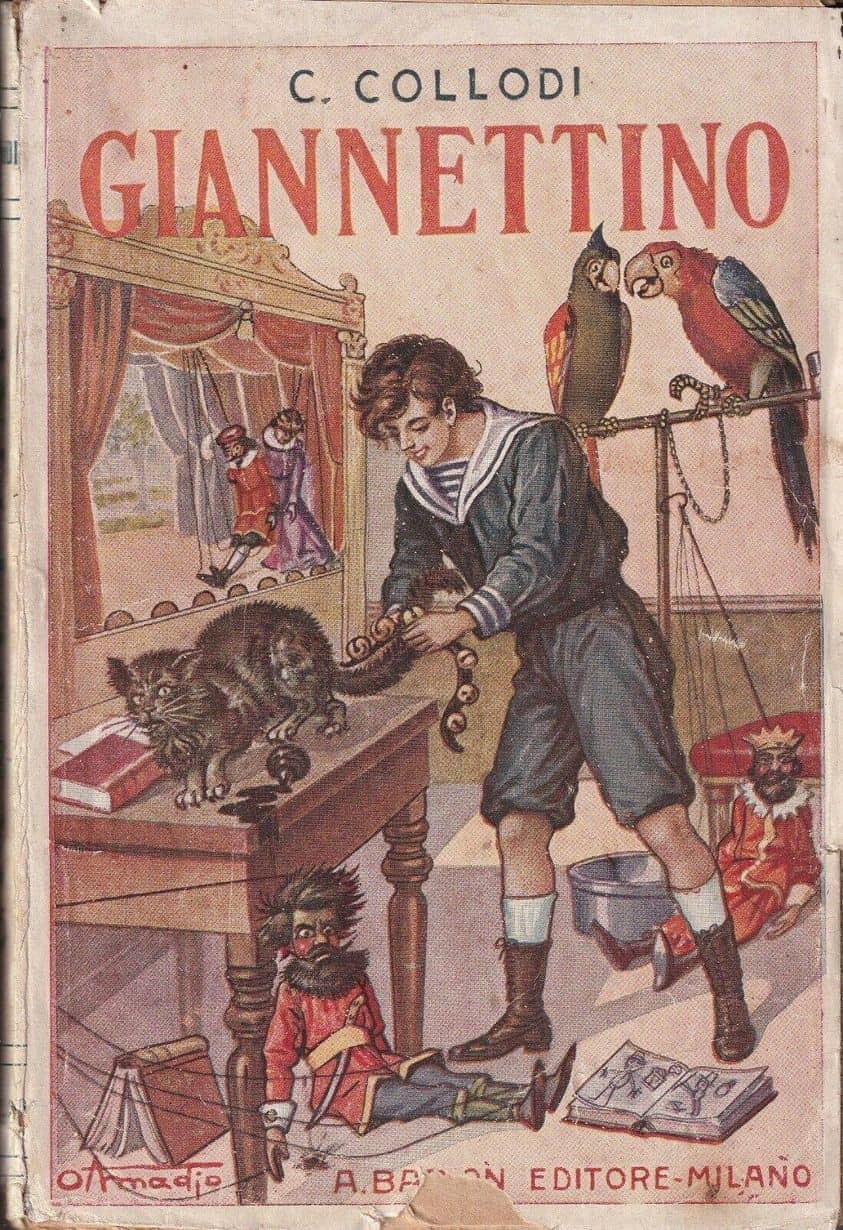

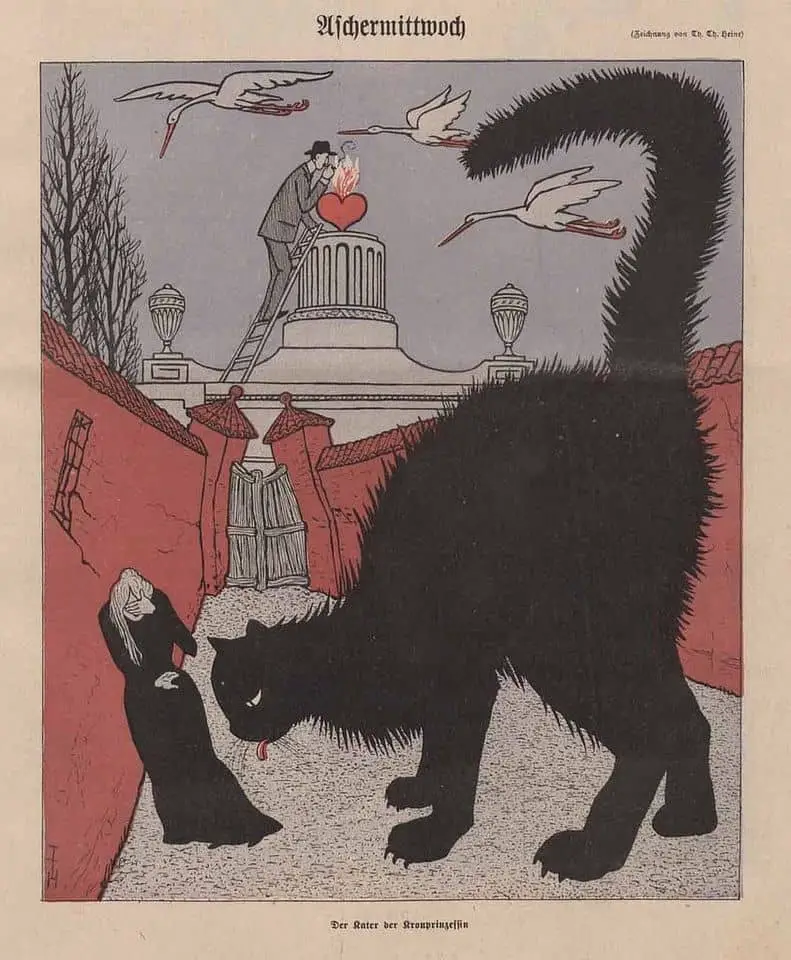

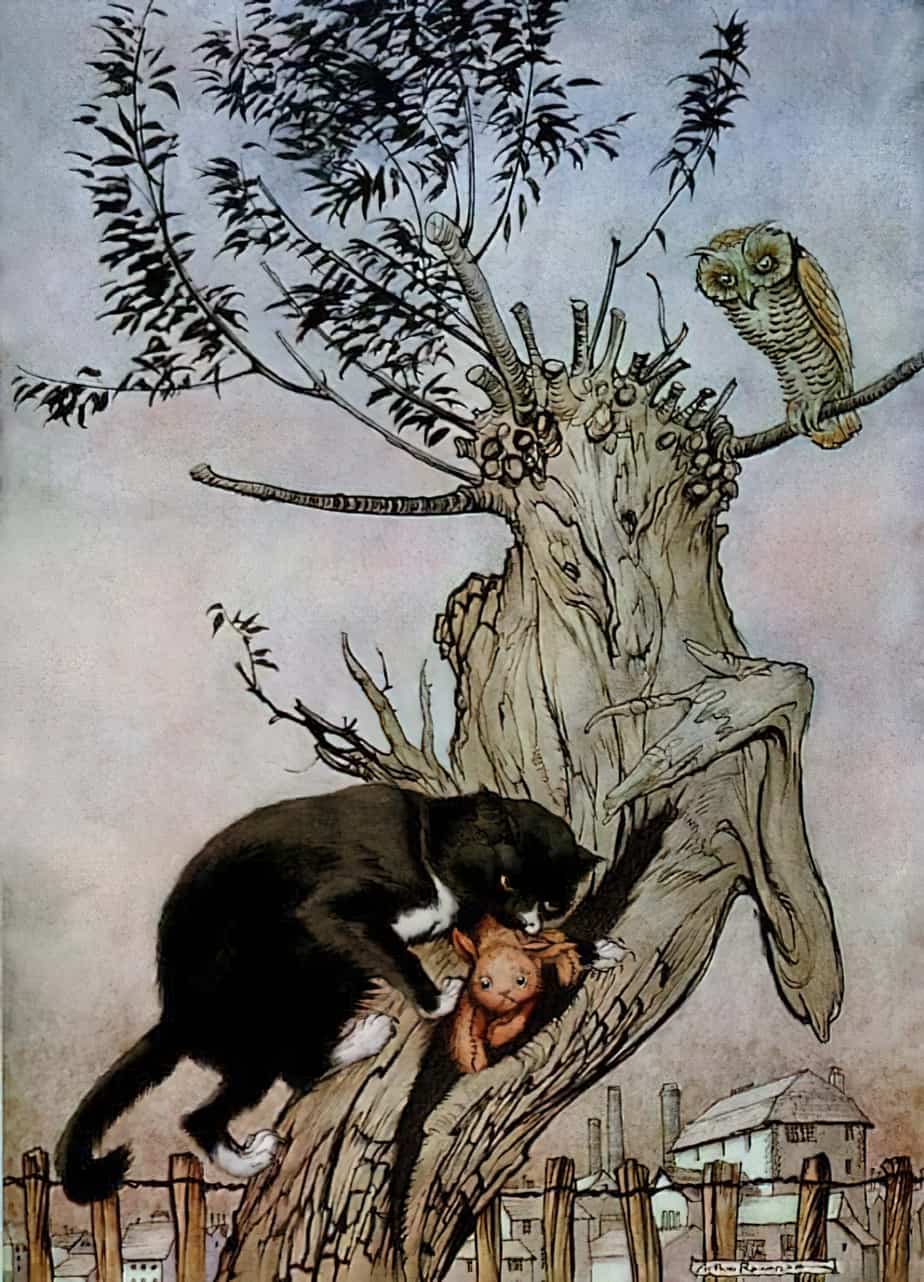

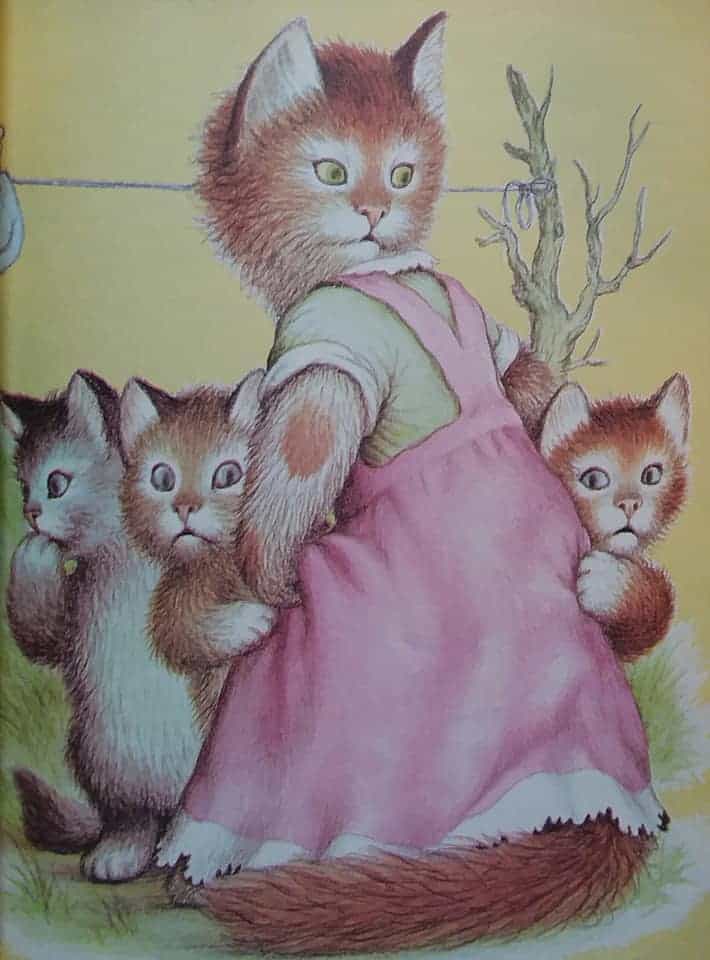

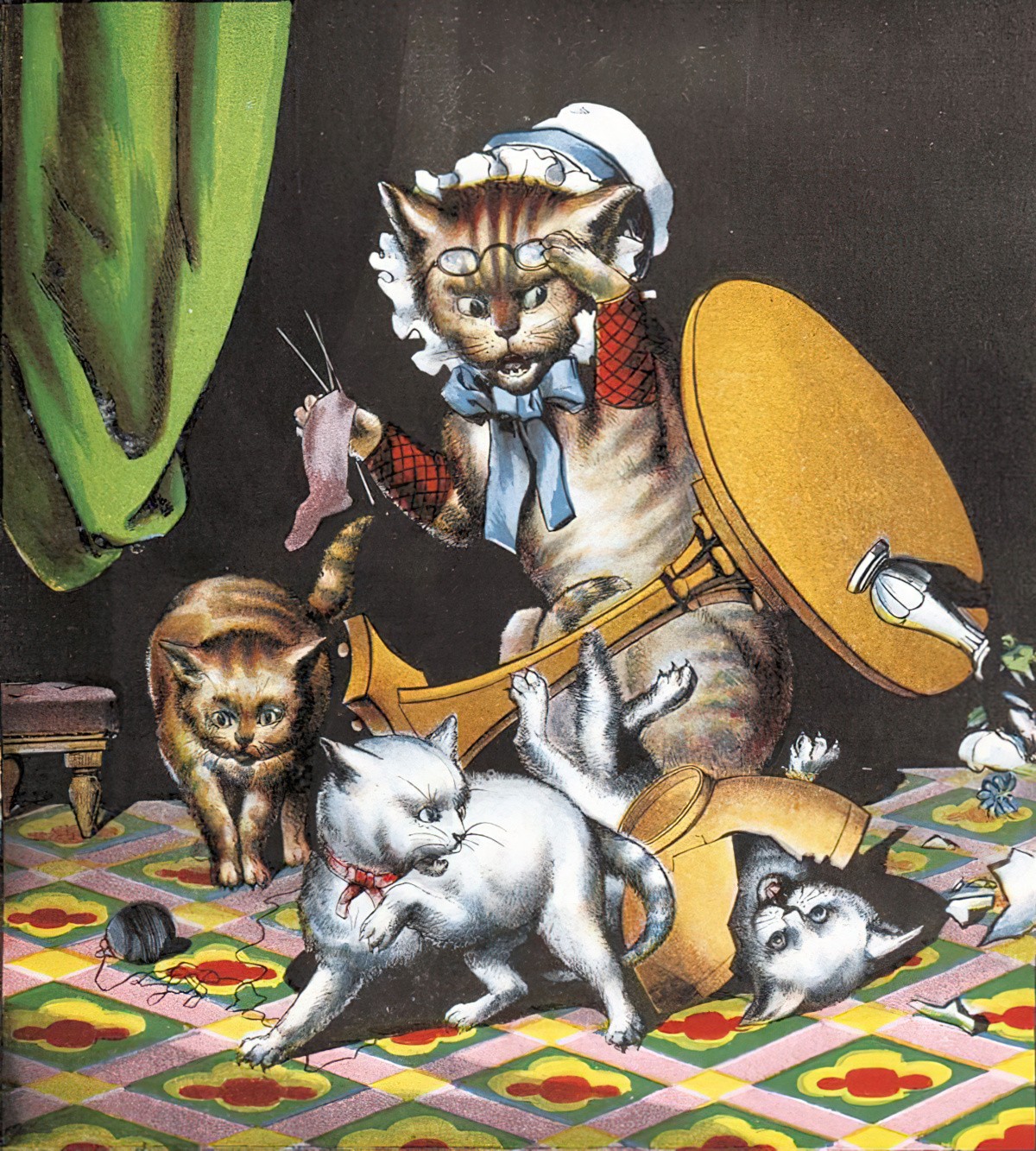

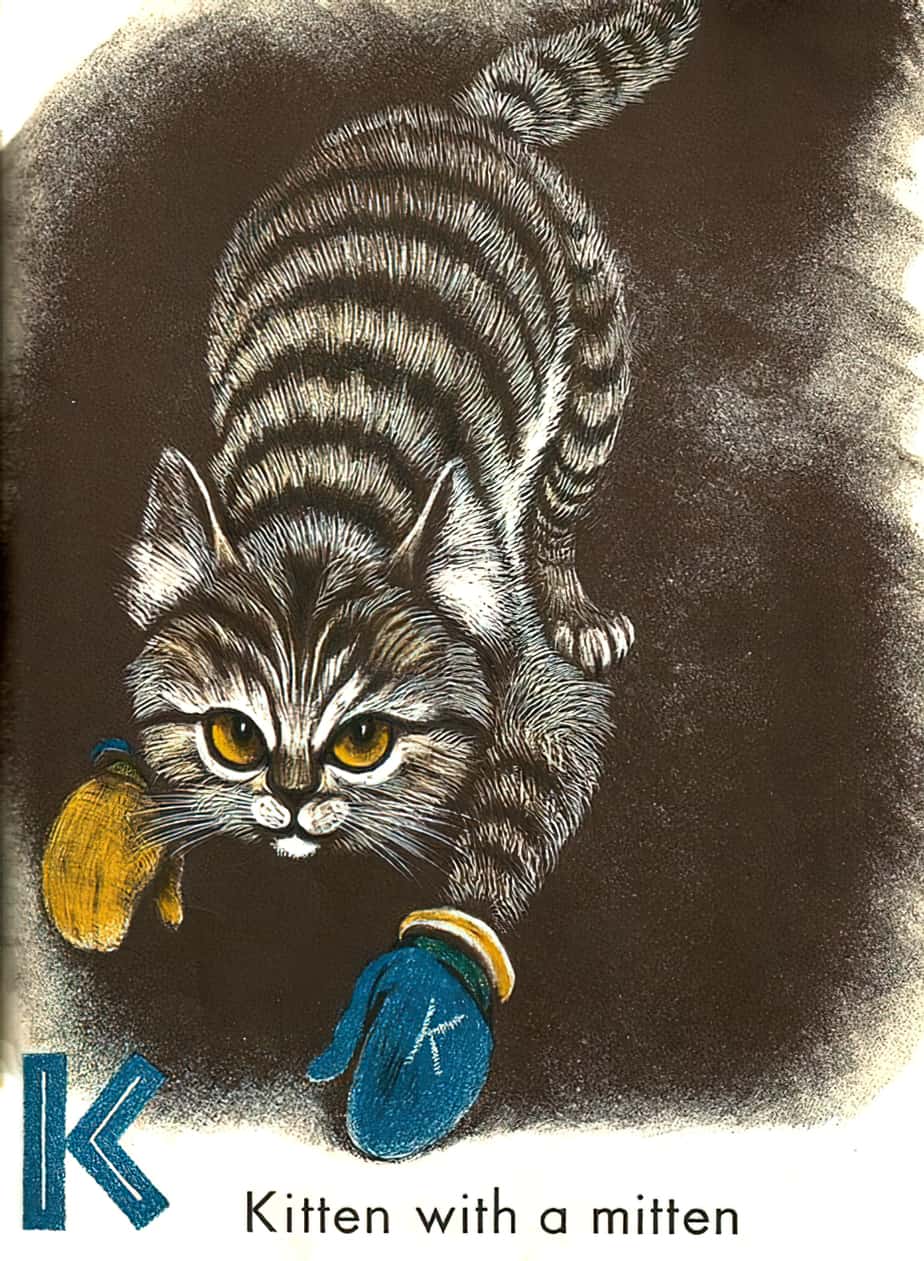

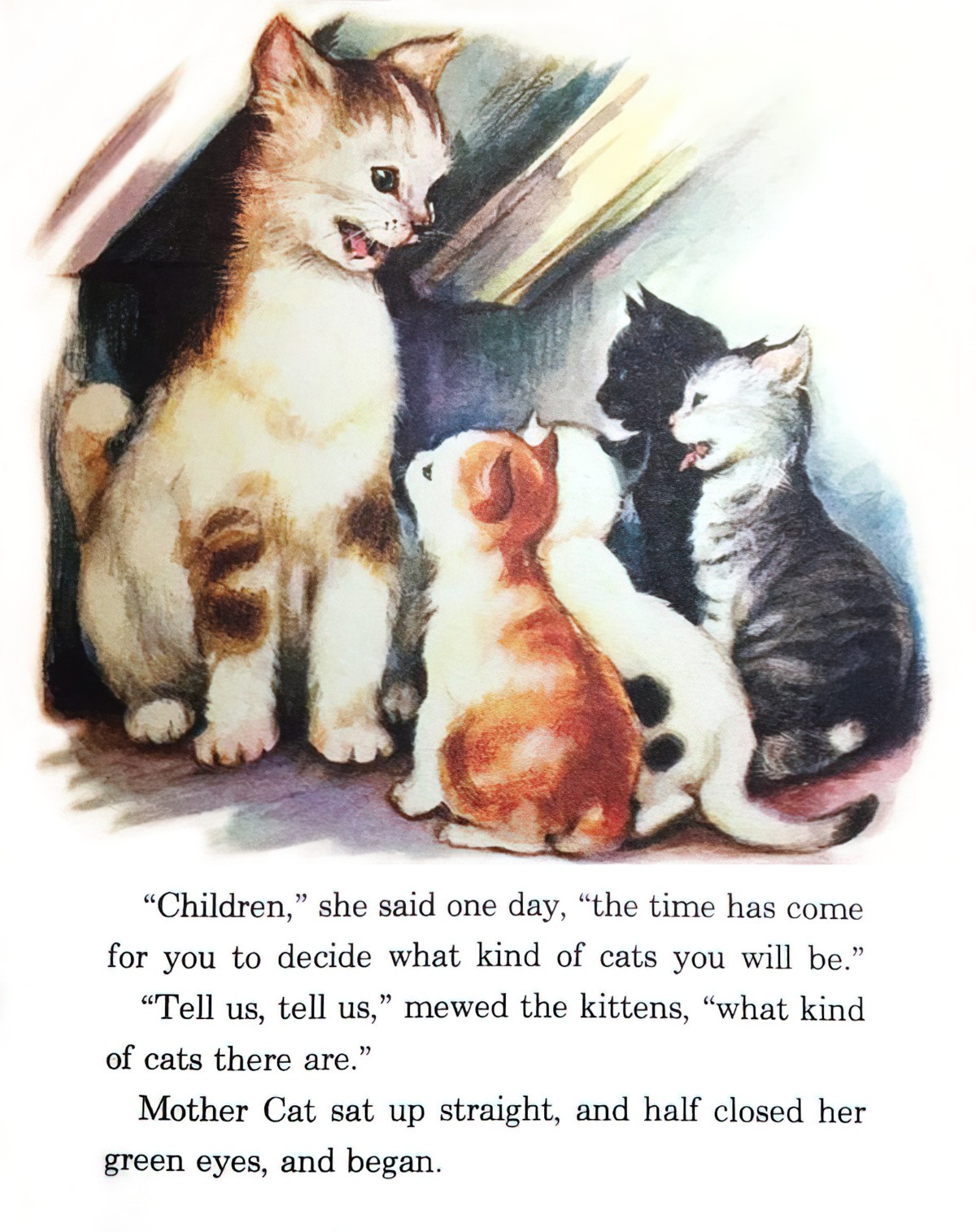

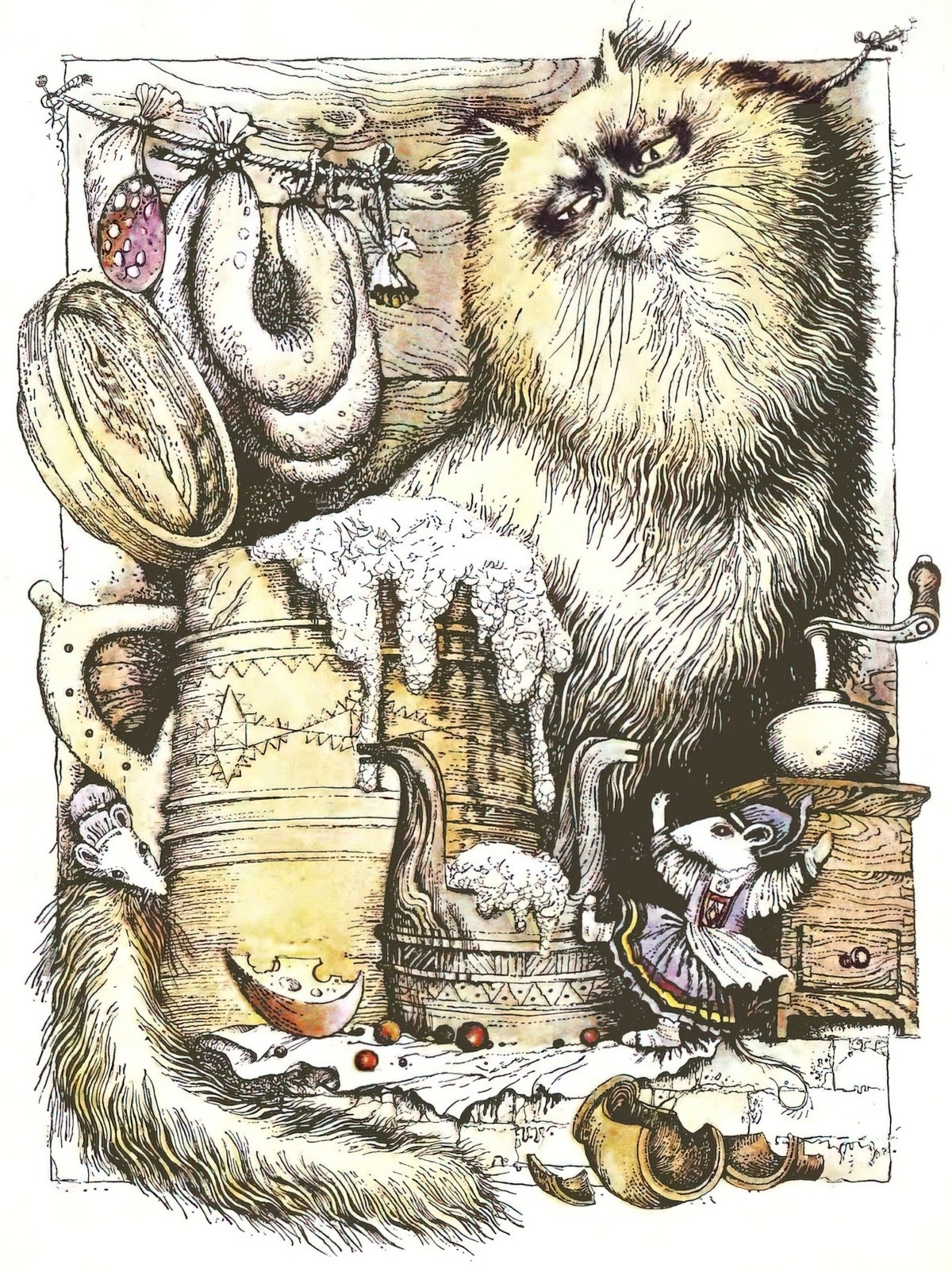

Despite being a cat lover, this is a collection of cat illustrations I personally feel unappealing. In some cases, the illustrator has deliberately gone for ‘unappealing’. In other cases, the lack of appeal is probably down to changes in aesthetics over time.

The change in cat illustration somewhat reflects the change in our attitudes towards cats, from familiars to loving pets.

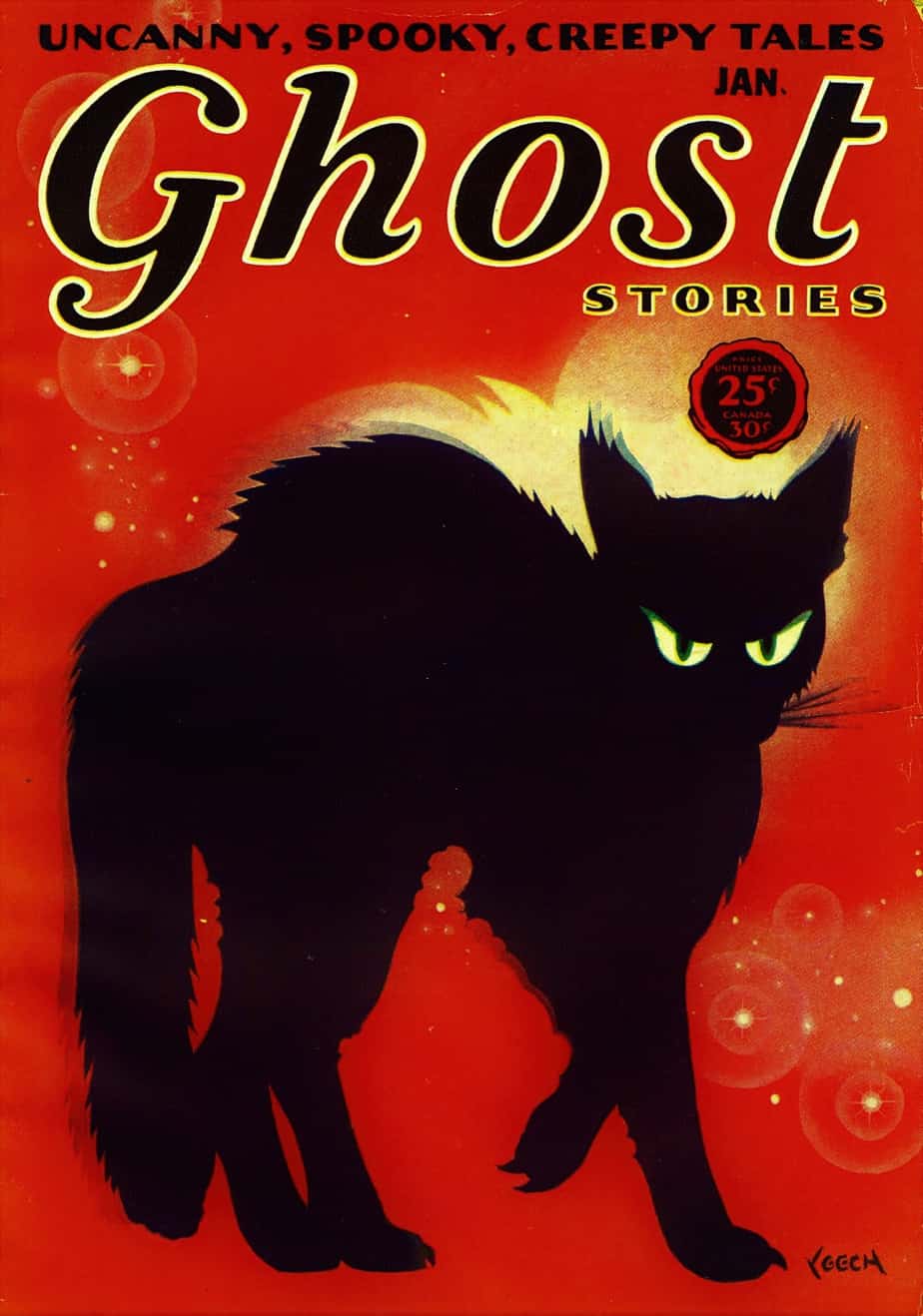

The view of cats as evil led to incredible cruelties toward them. During witch hunts, cats were burned together with their mistresses. At the same times, there is evidence of cats being put into walls of newly built houses to bring luck.

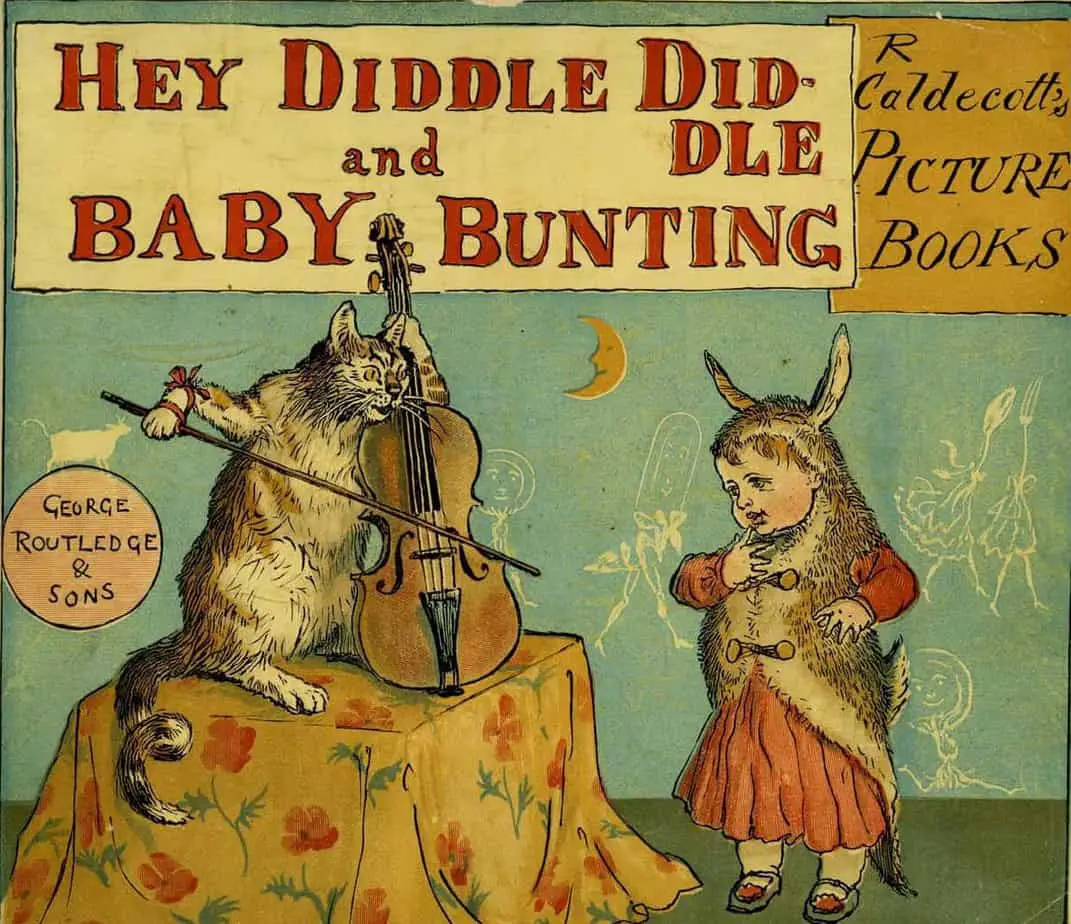

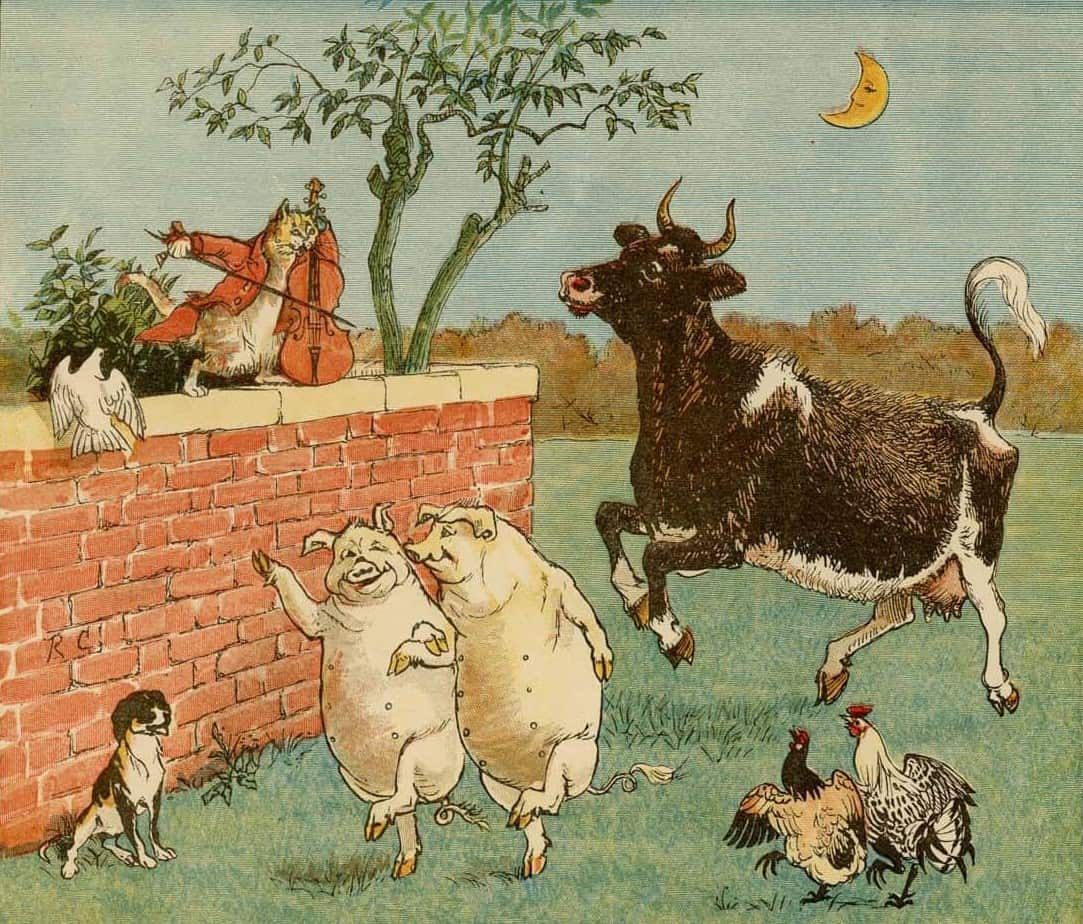

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the cat’s reputation was exculpated, and cats became popular pets in upper- and middle-class families, which is, among other things, reflected in numerous nursery rhymes, fables, cartoons, children’s stories and picturebooks. Cats became benign and often sweet characters, adapted to children’s and family reading. Most of modern cat stories are picturebooks portraying anthropomorphic cats, representing humans. The shape is, just as in George and Martha books, arbitrary and interchangeable. It is hardly worth mentioning the abundant felines rubbing against their owners’ feet or purring on their laps, merely to create an atmosphere. In hundreds of books, a child gets a kitten for pet. Occasionally, a black cat may prompt, most often erroneously, that its owner is a witch.

Maria Nikolajeva, Power, Voice and Subjectivity in Literature for Young Readers

Even in the 1870s, people were obsessed with ridiculous photos of cats, from io9

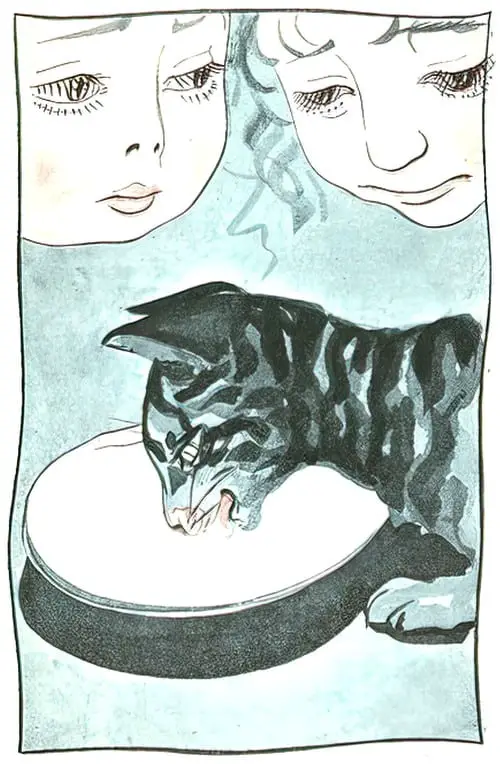

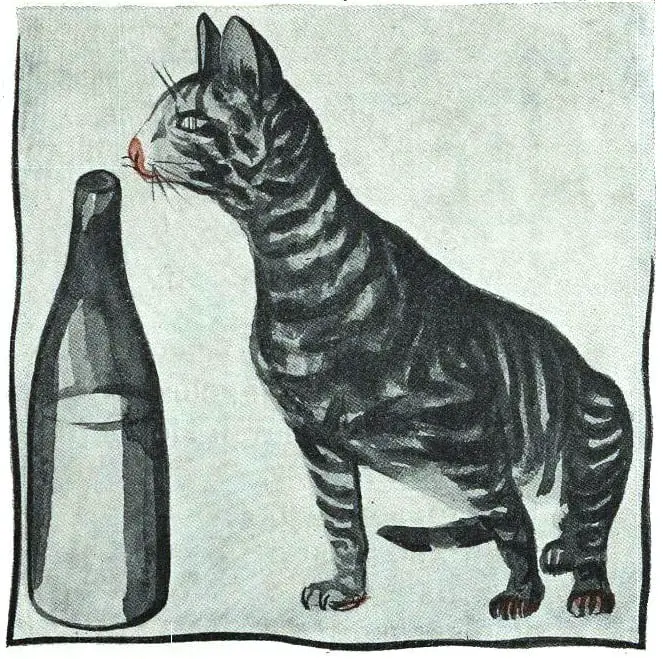

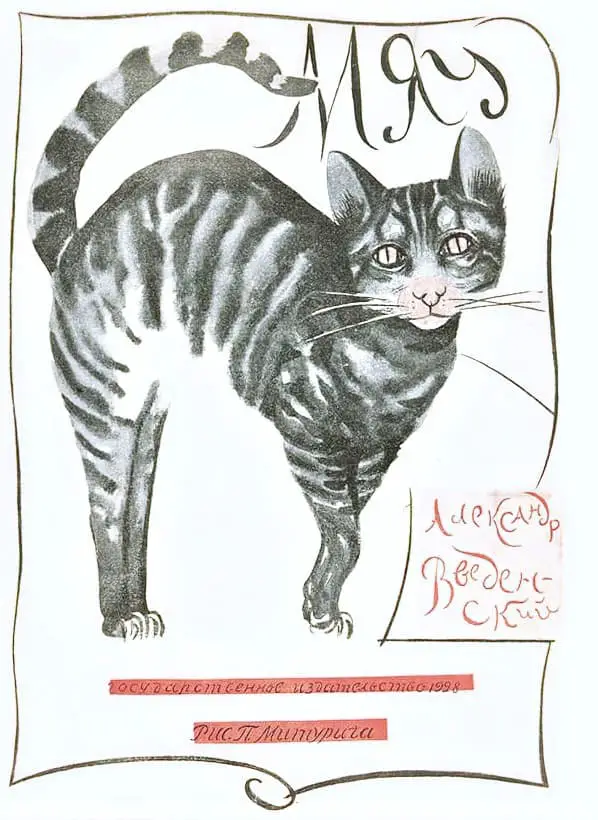

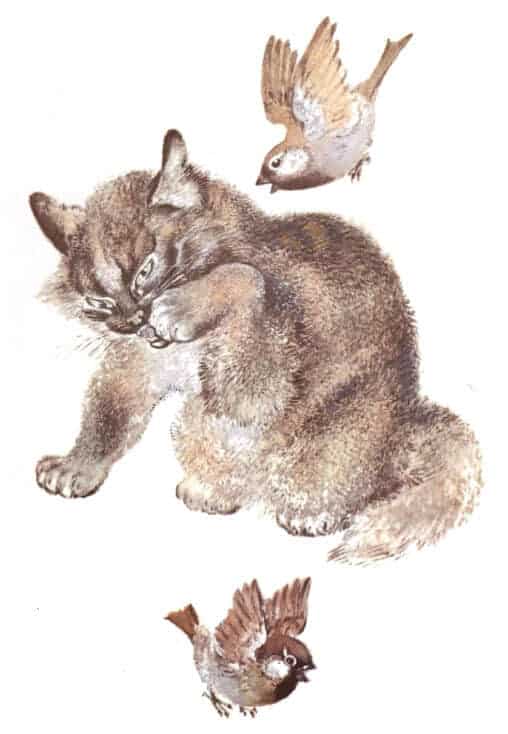

The following illustrations are from a 1928 Russian children’s picture book called Meow written by Aleksandr Vvedensky illustrated by Pyotr Miturich.

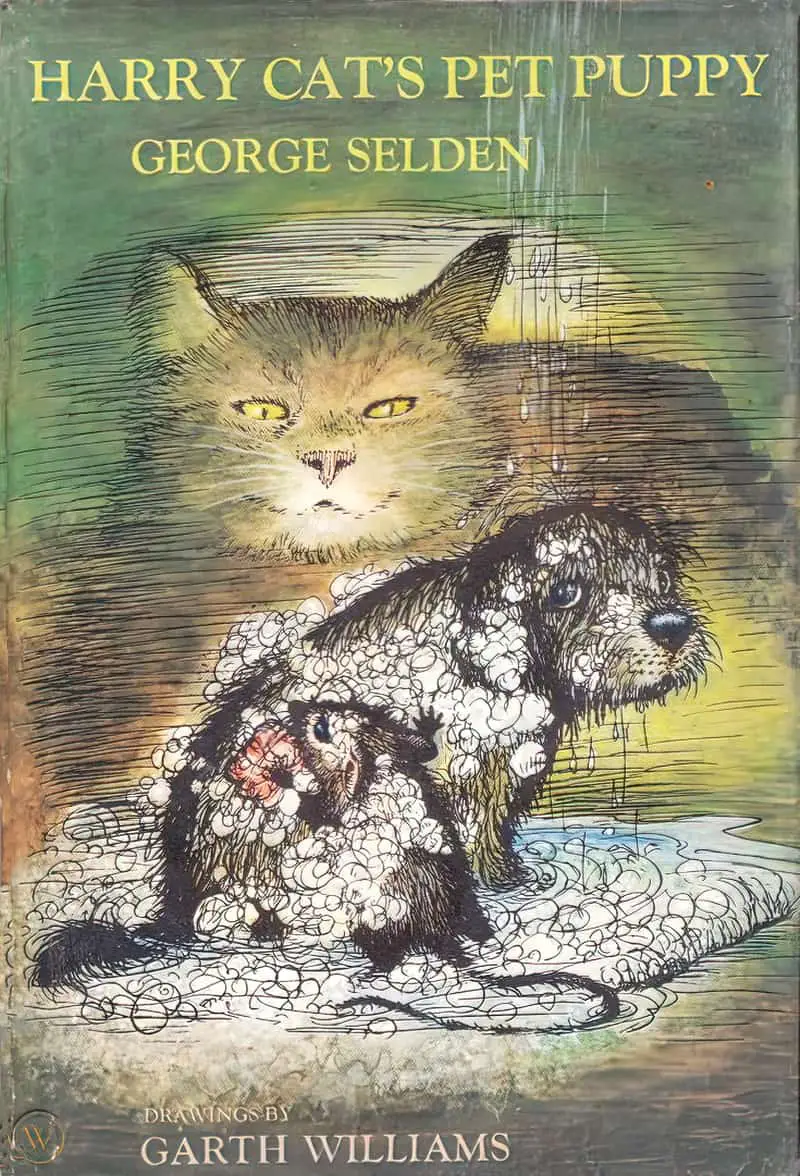

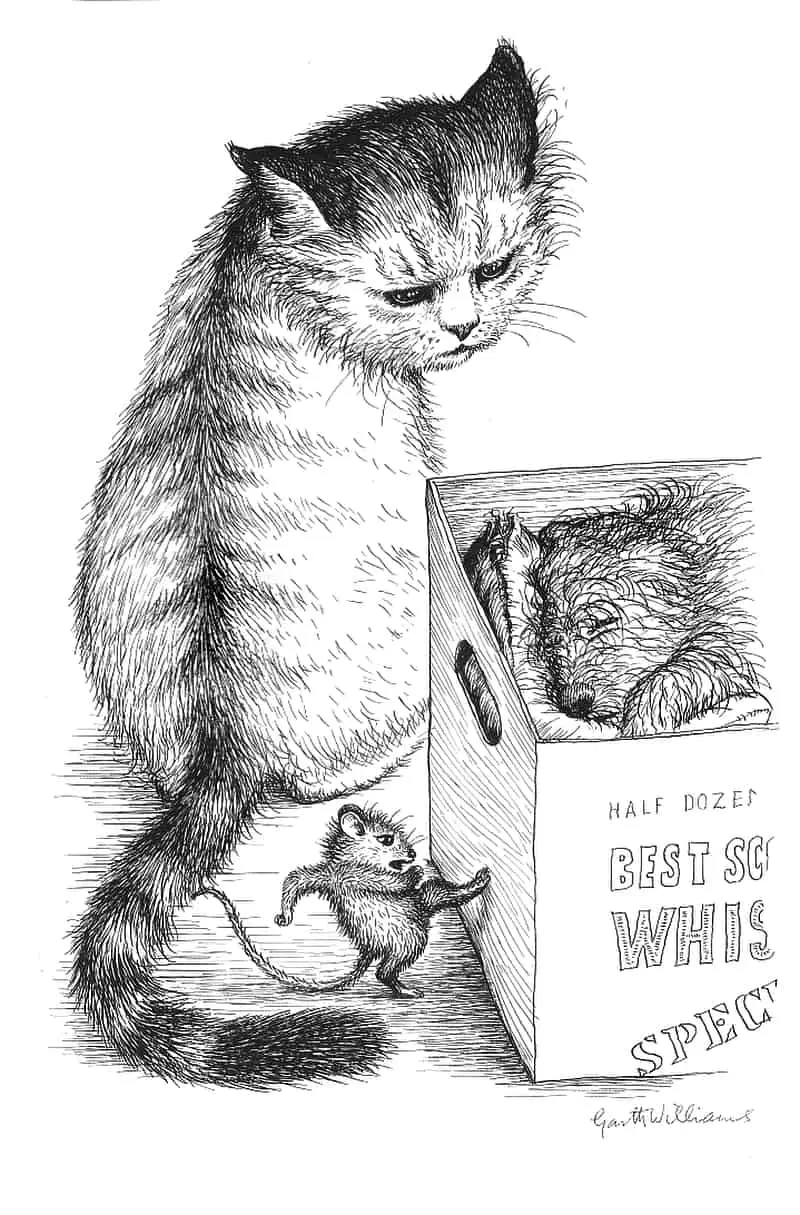

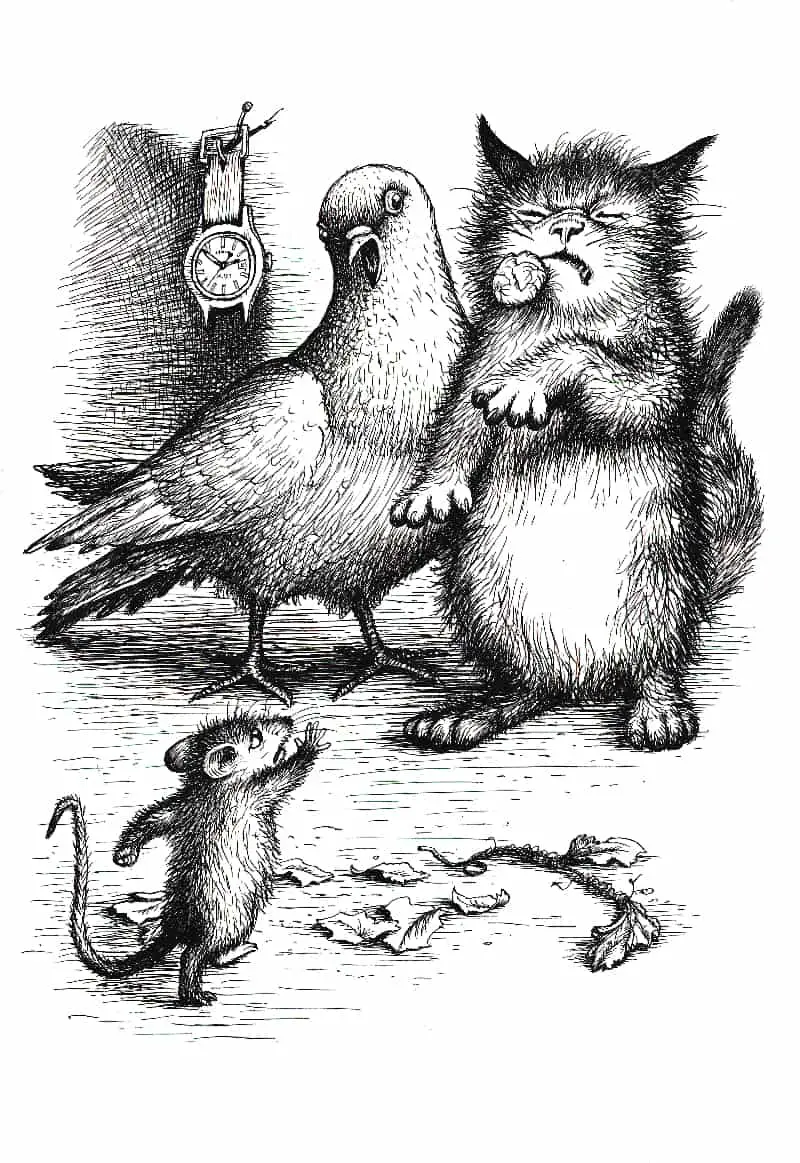

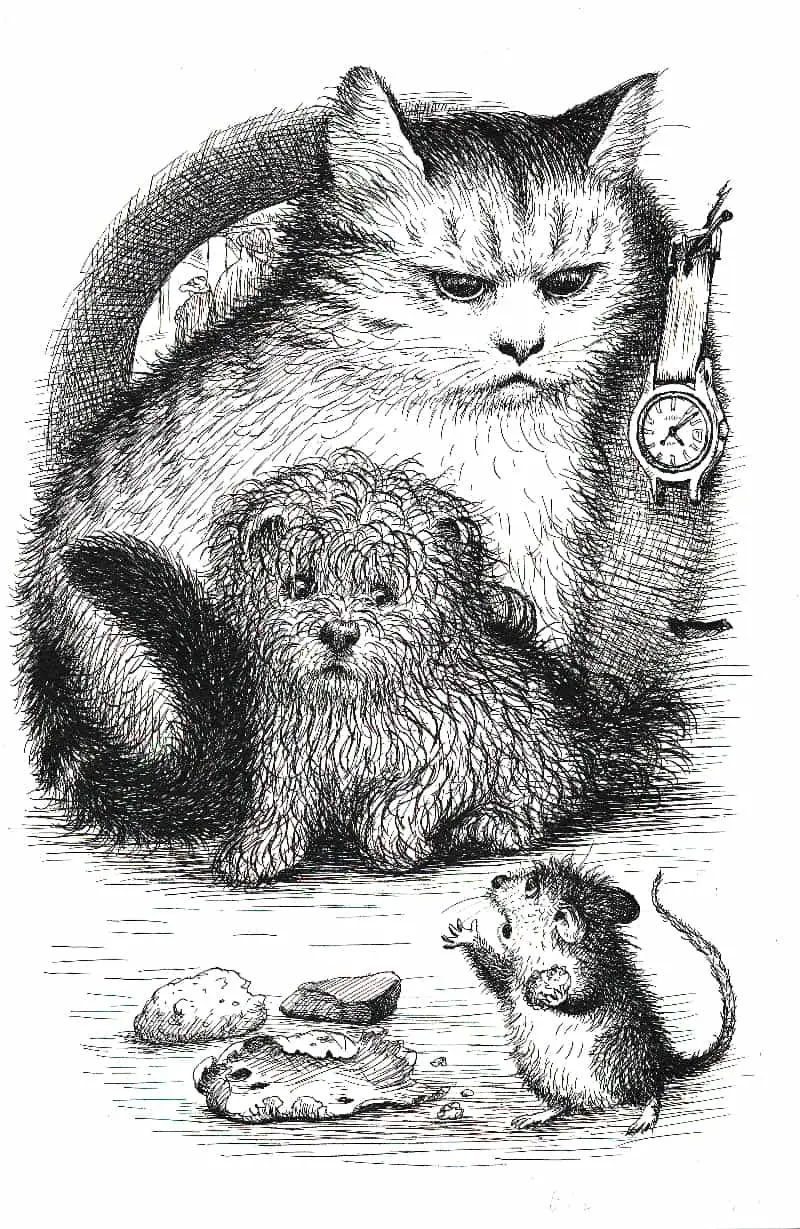

Harry Cat’s Pet Puppy 1973 Illustrated by Garth Williams (1912 – 1996). The dogs in these illustrations are far more appealing than the cat.

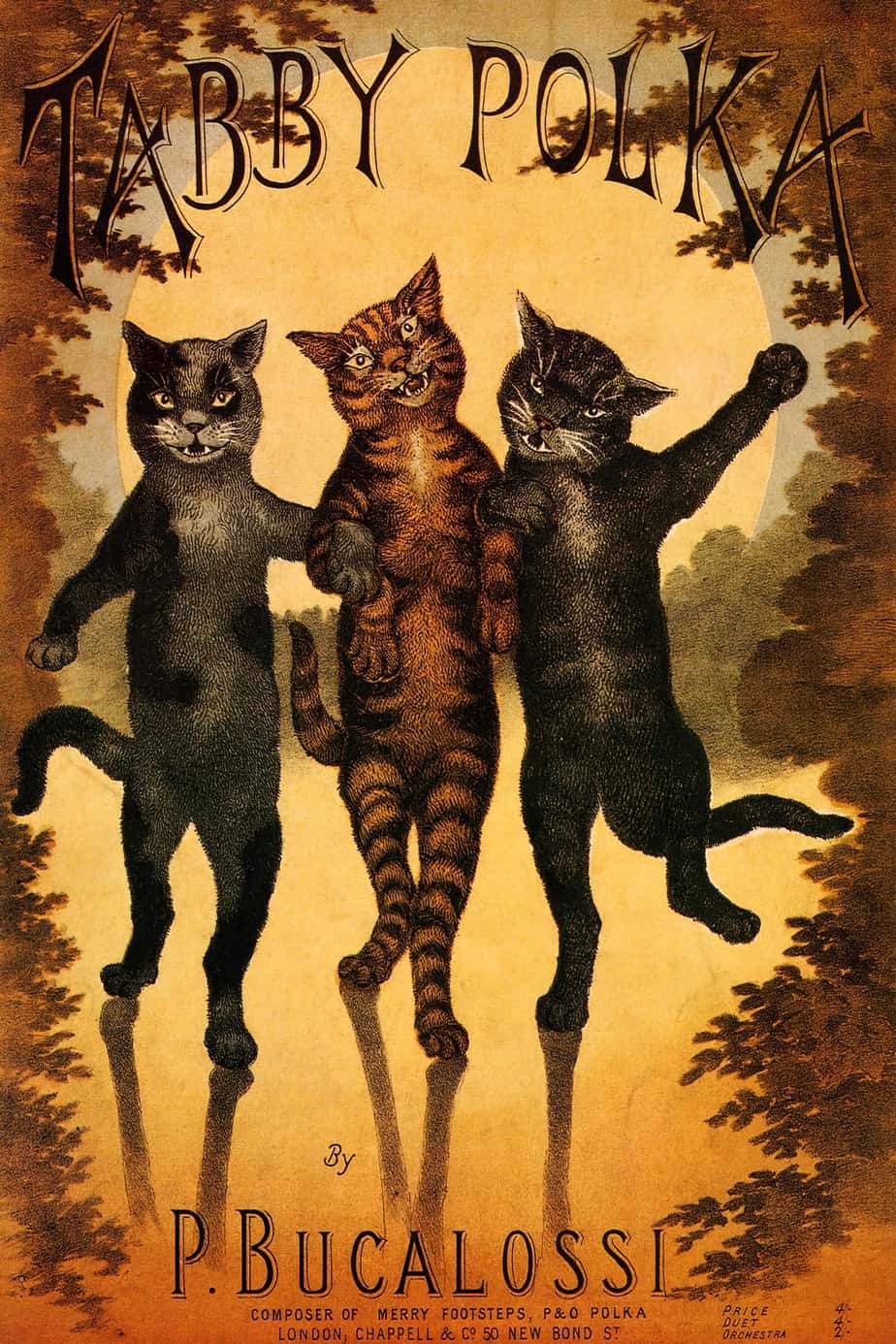

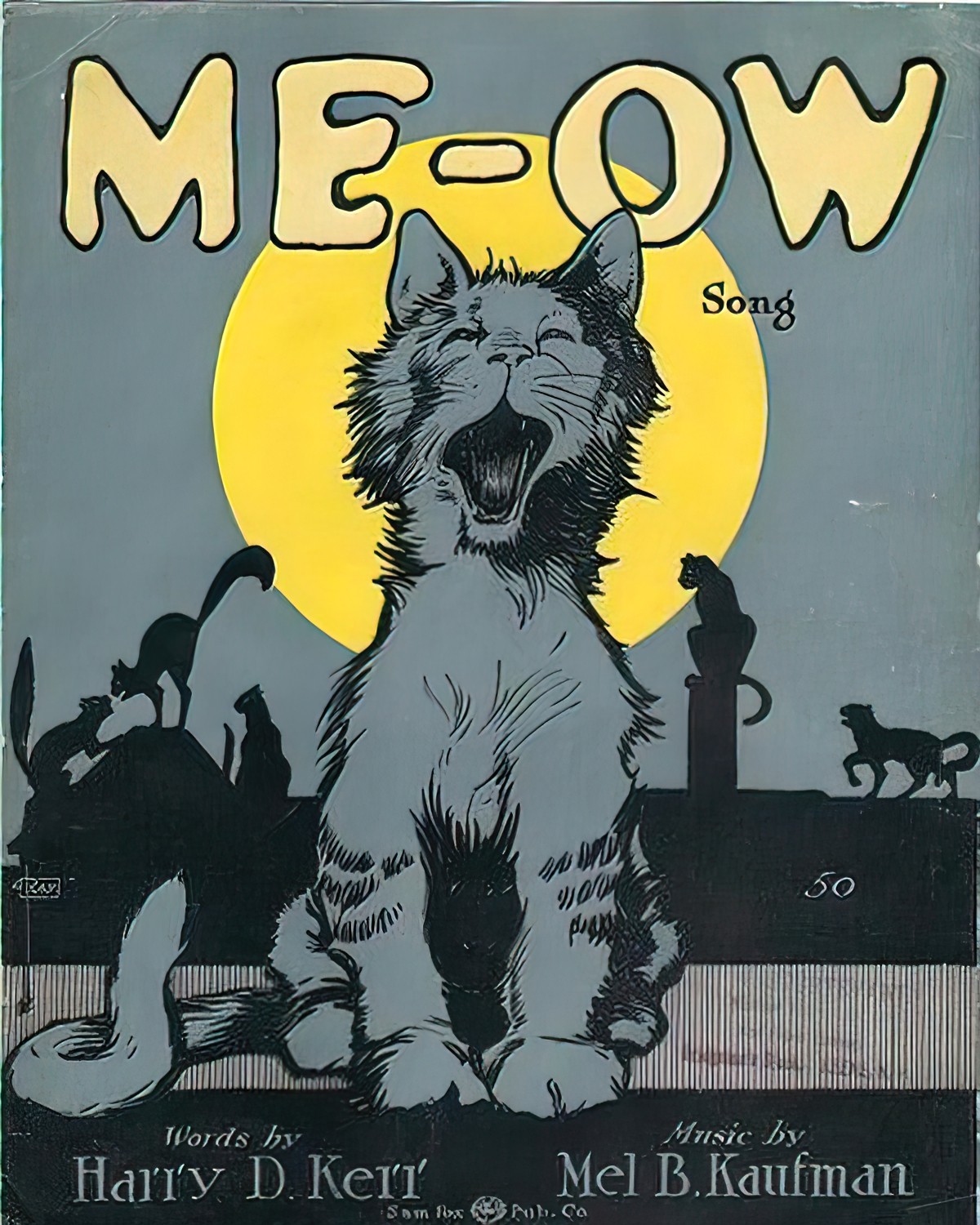

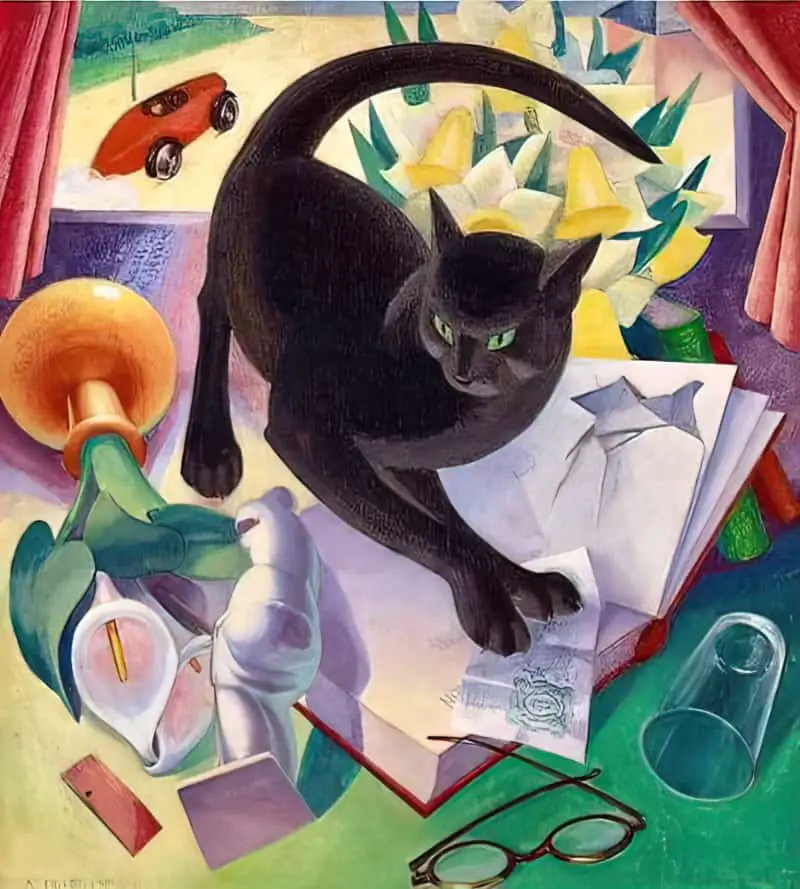

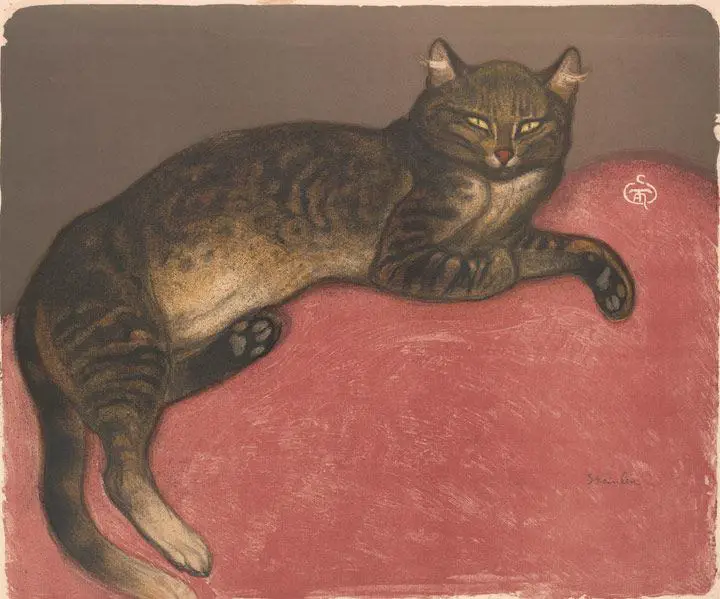

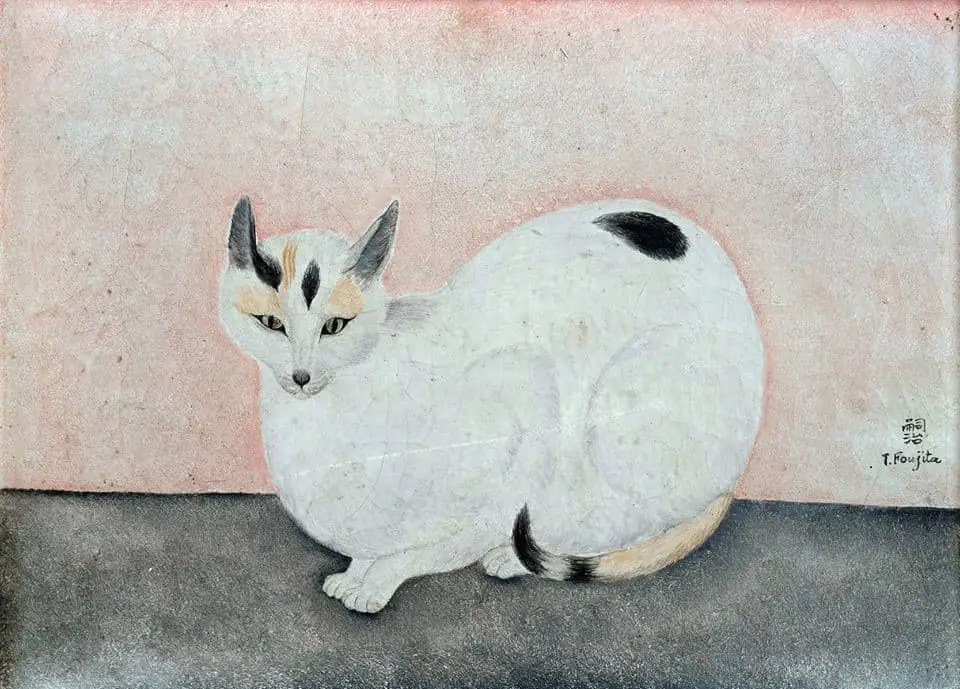

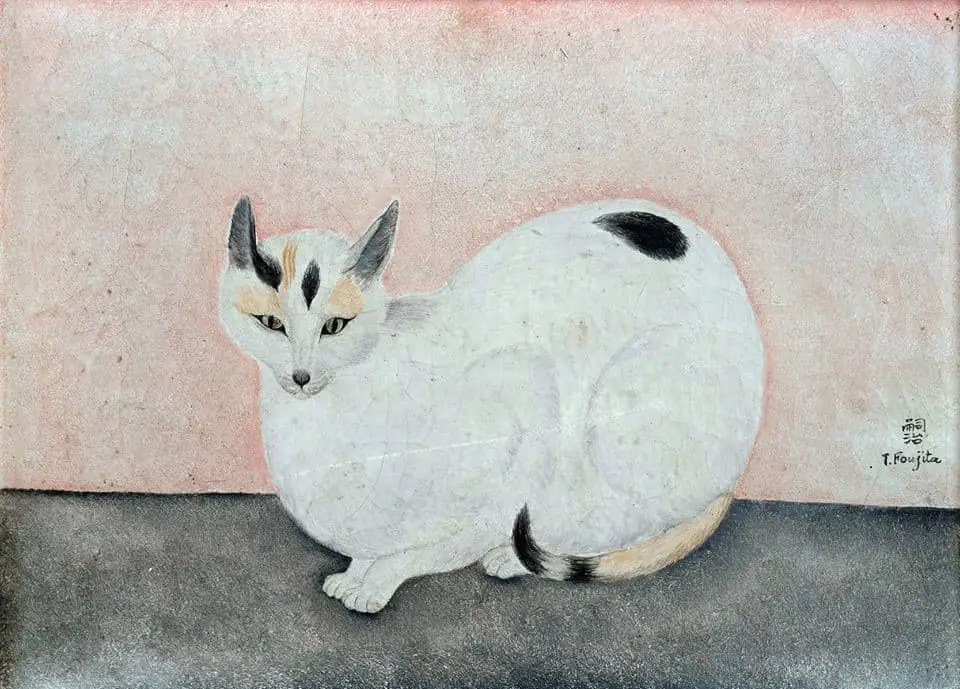

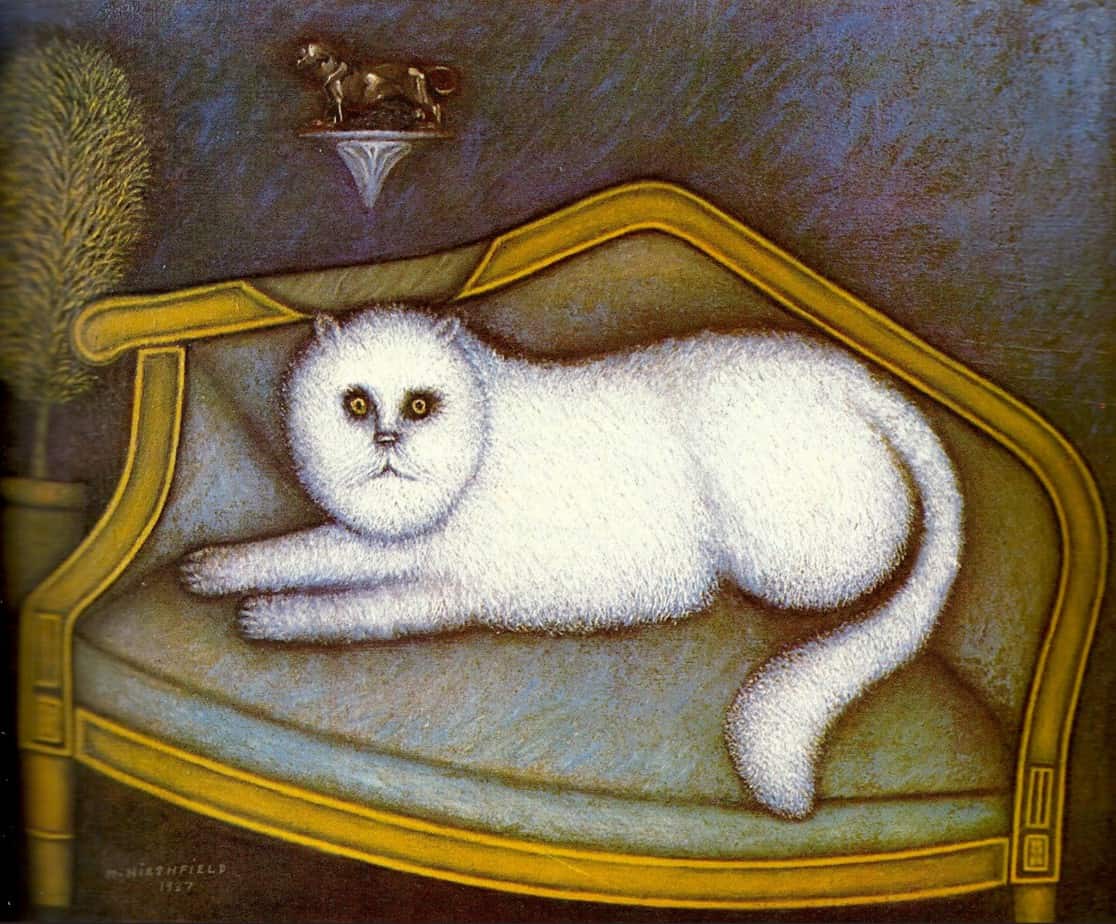

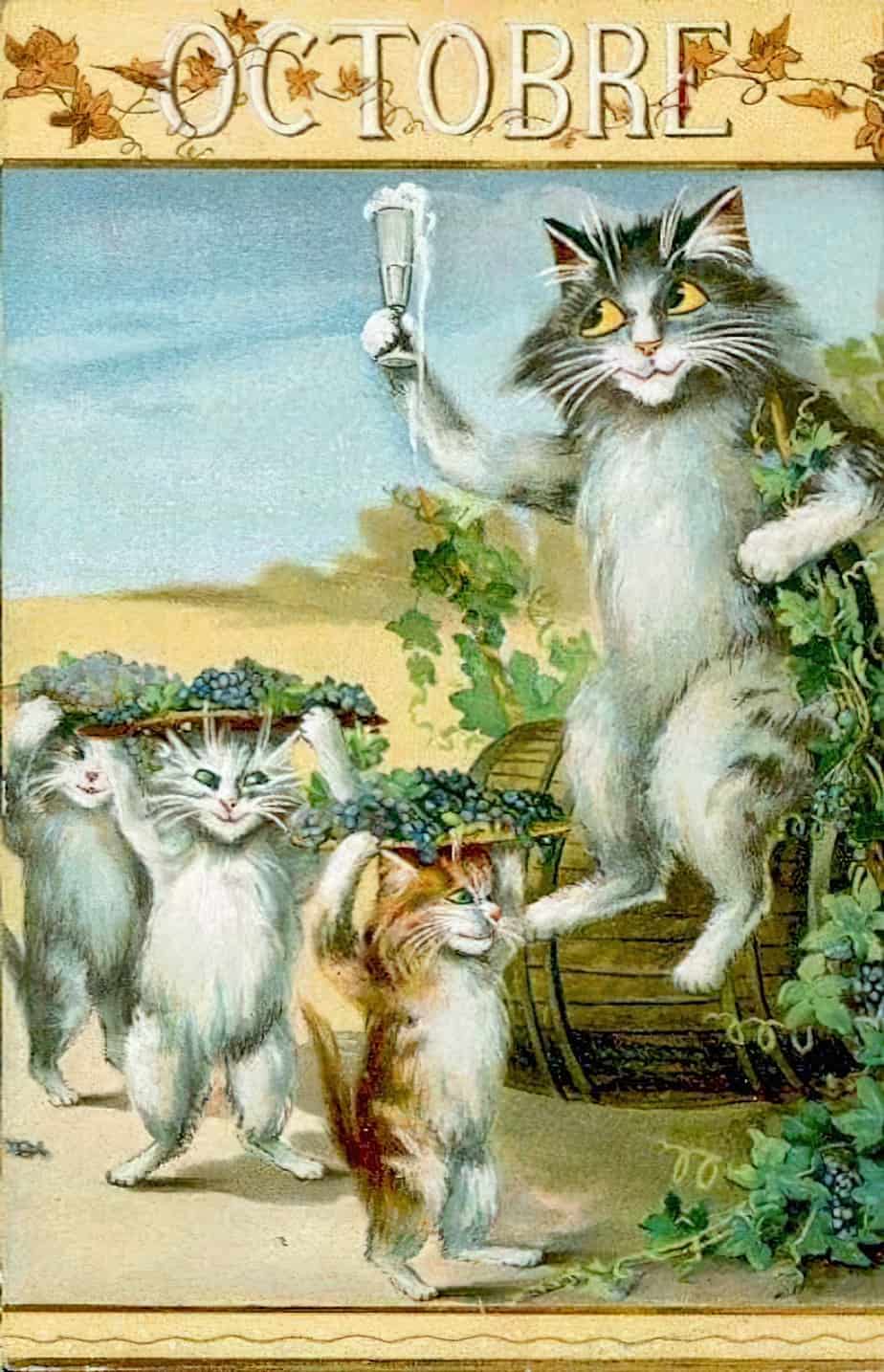

EARLY 20TH CENTURY CATS IN ART

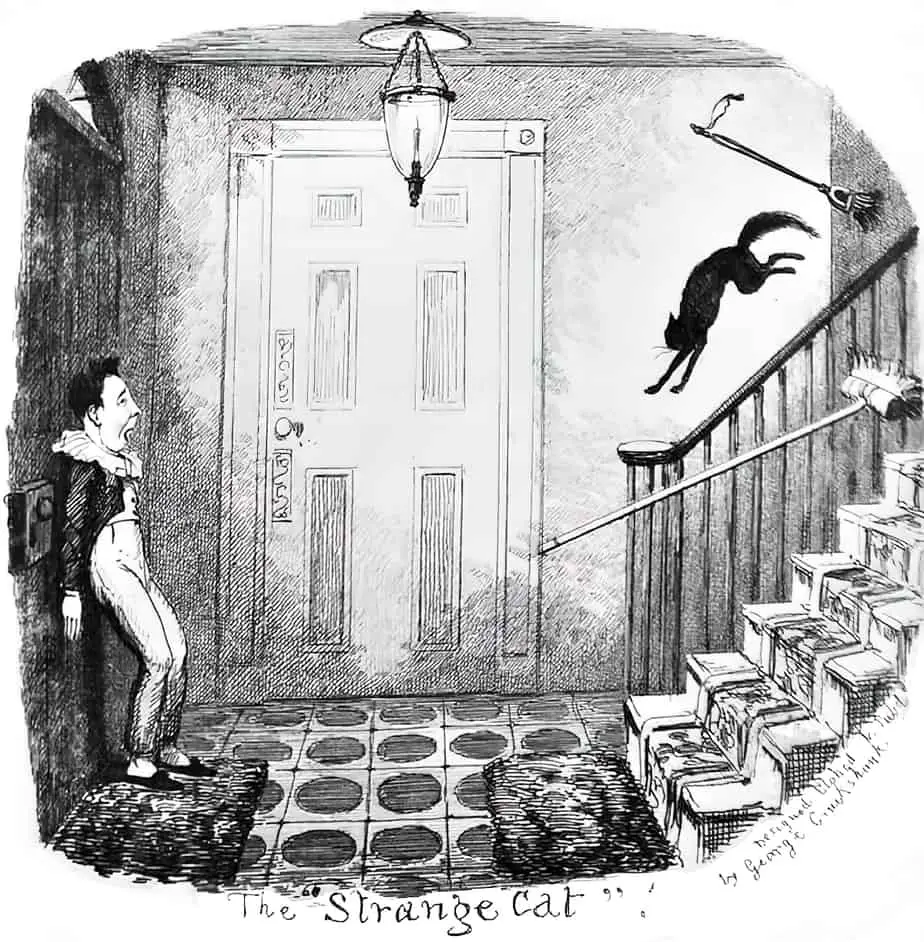

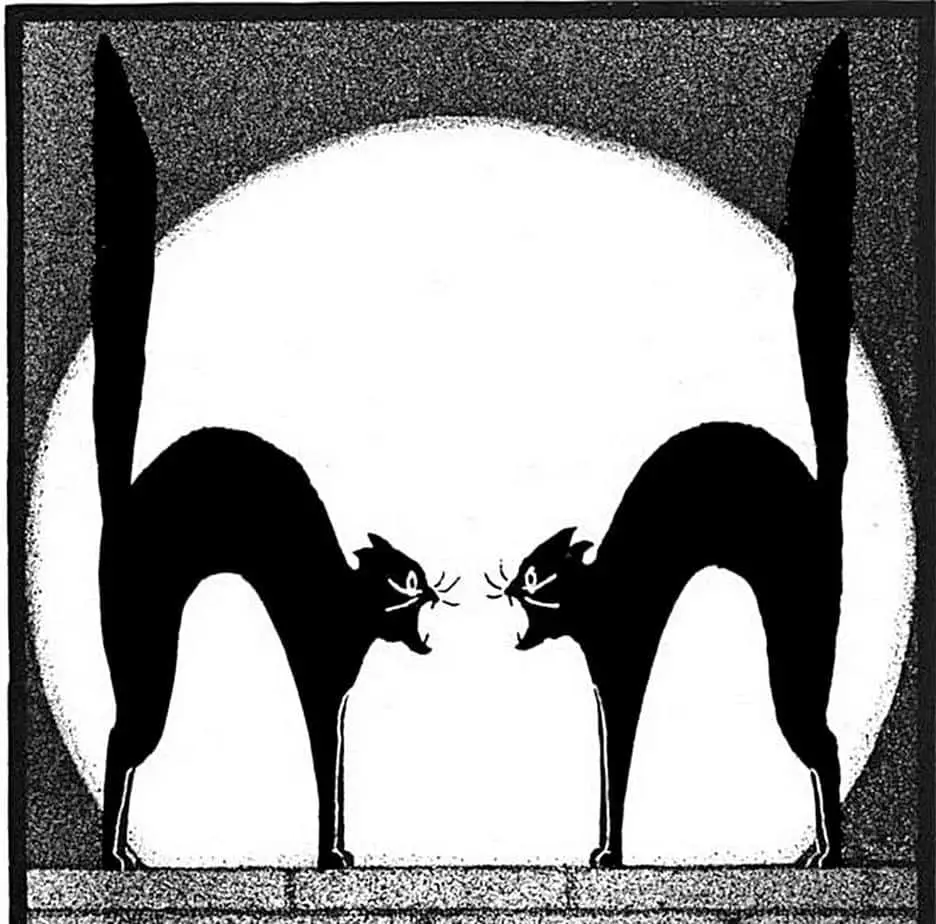

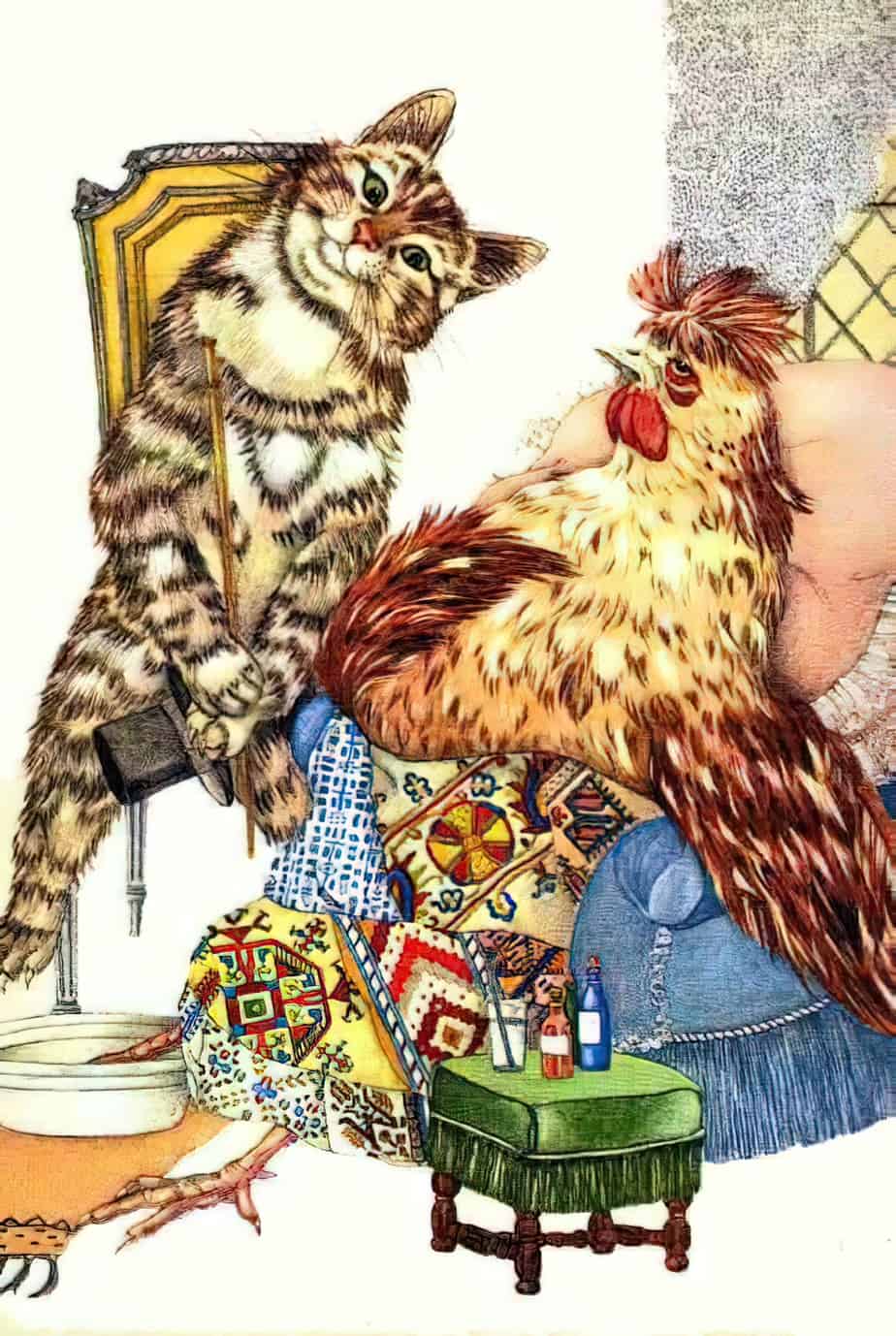

The early decades of the 20th century offer a cornucopia of sly, mean-looking cats. I’m not convinced all of them are meant to look mean. I think some of them are meant to look cute, or at least realistic. Others are clearly meant to convey exactly what they do.

Cats have one or two grooming habits which wouldn’t go down in polite human society, but we put up with this anyhow. A cat in the painting below grooms itselfl, another gets up to mischief with the candle and another stares into a mirror.

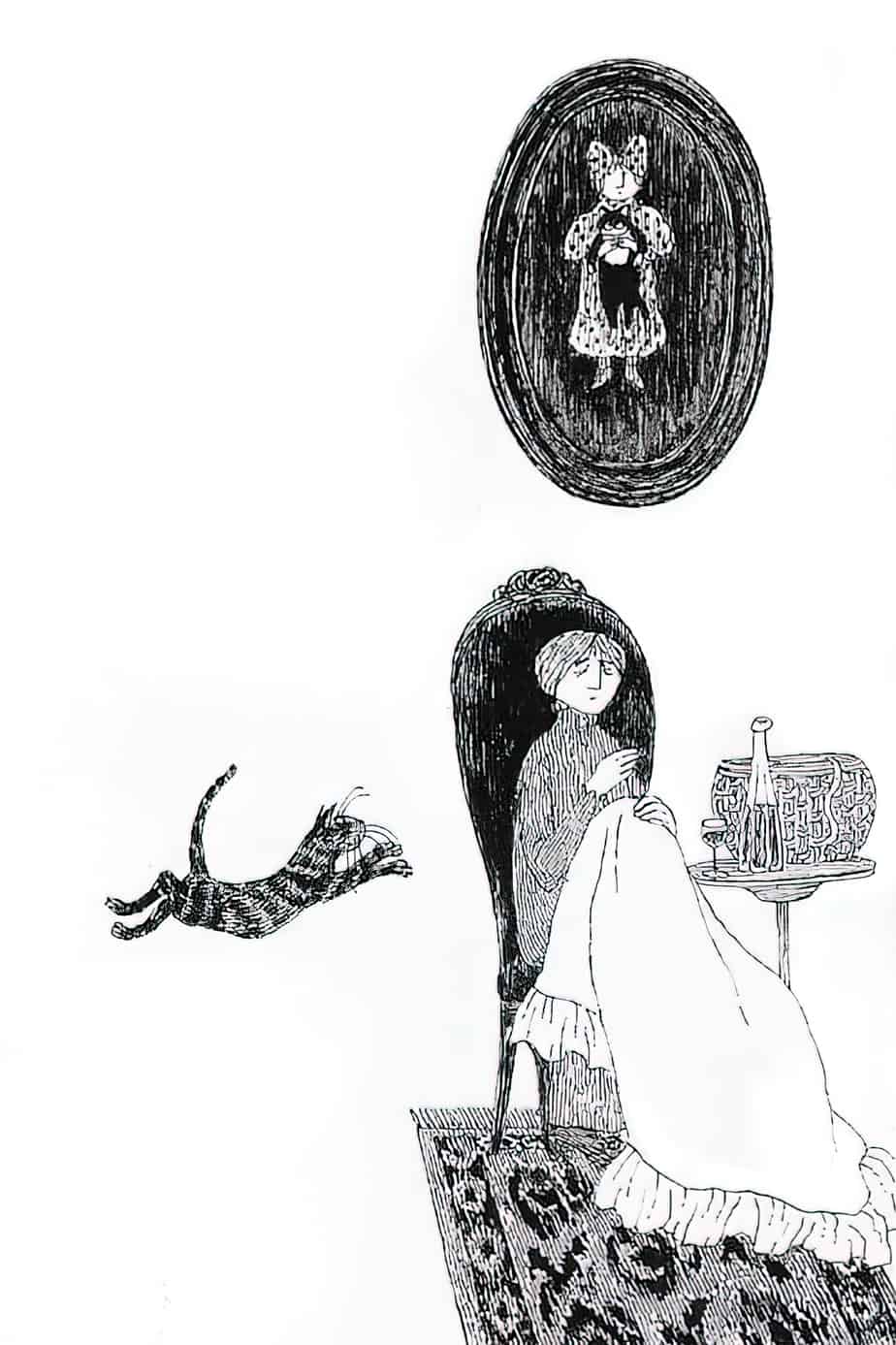

Mirrors, cats and various other items historically attract a disproportionate amount of superstition. Both mirrors and cats have come to be associated with witchcraft.

Perhaps this explains why I find the image below creepy.

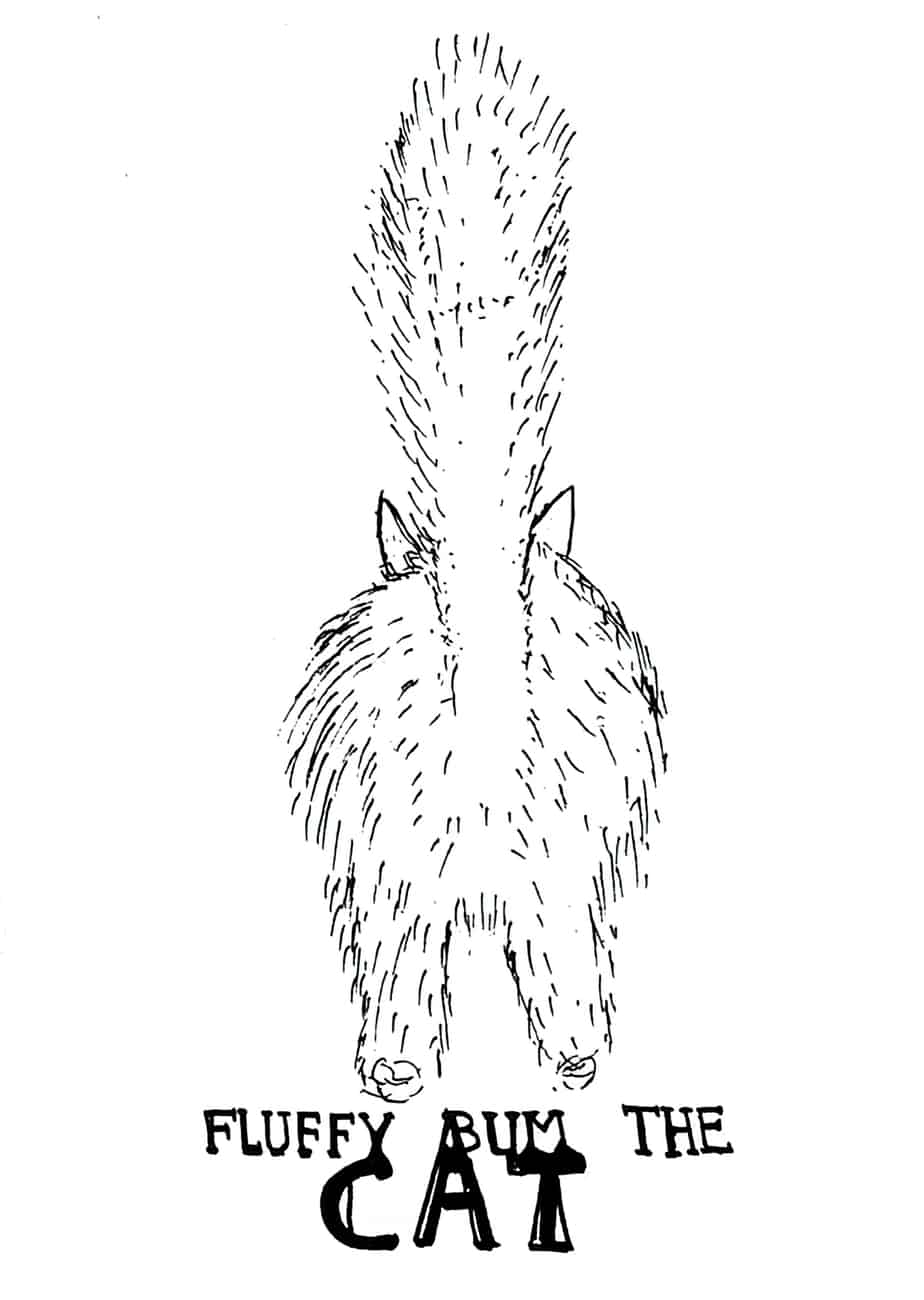

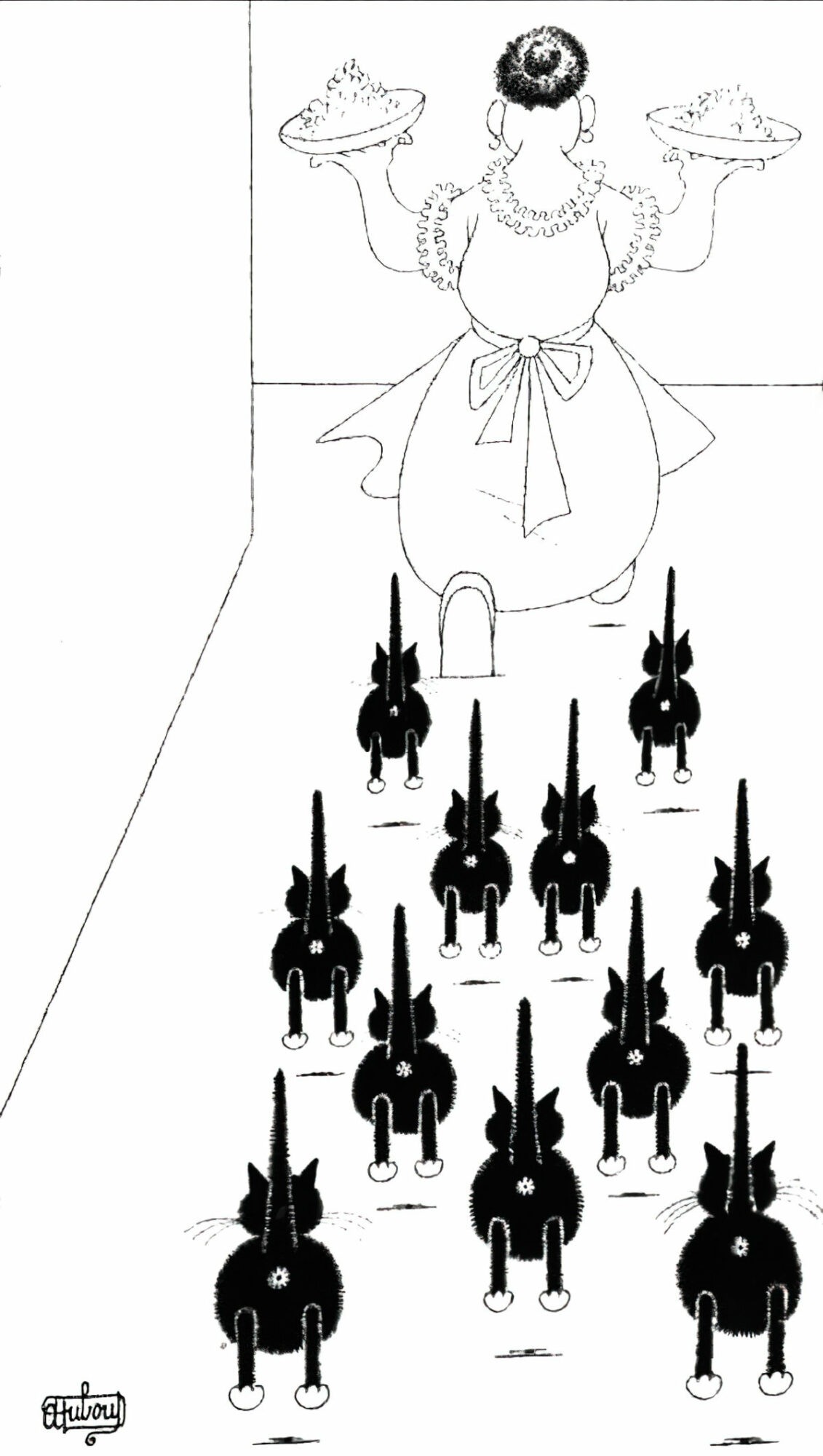

The illustrations below comically emphasise a part of cat anatomy which we see more of than we would like.

Medieval Paintings of Cats Licking Their Butts

The life and business of cats, Hermann van der Moolen, 1843 – c. 1920

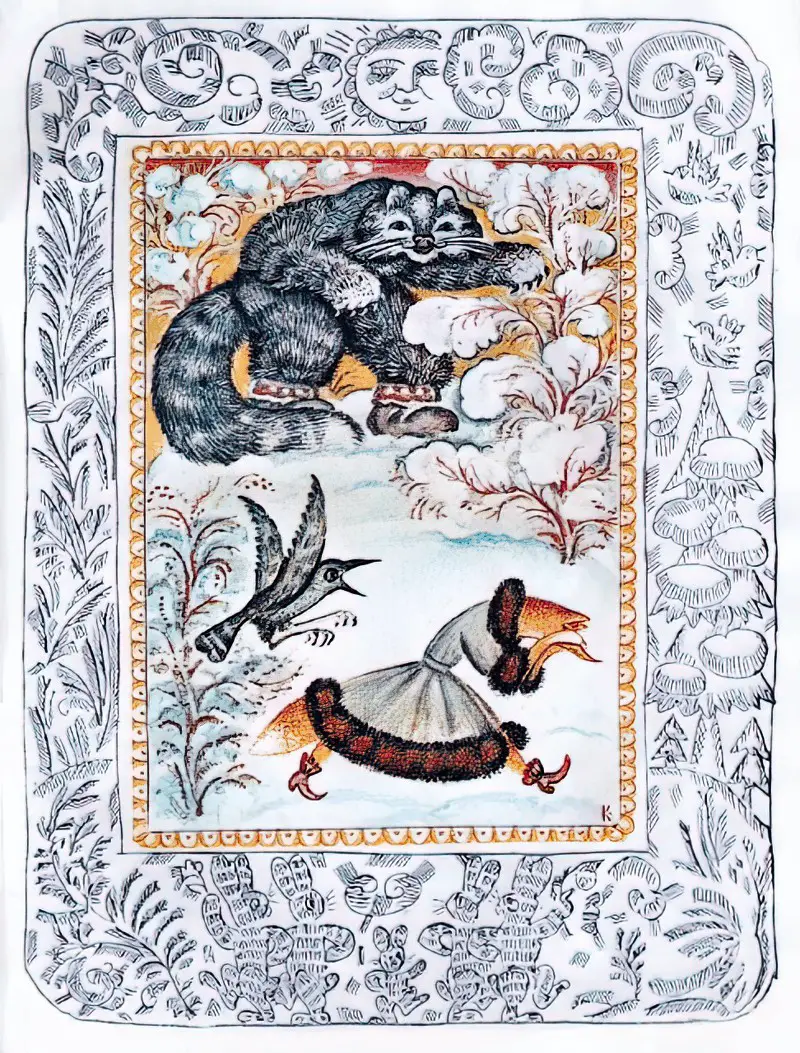

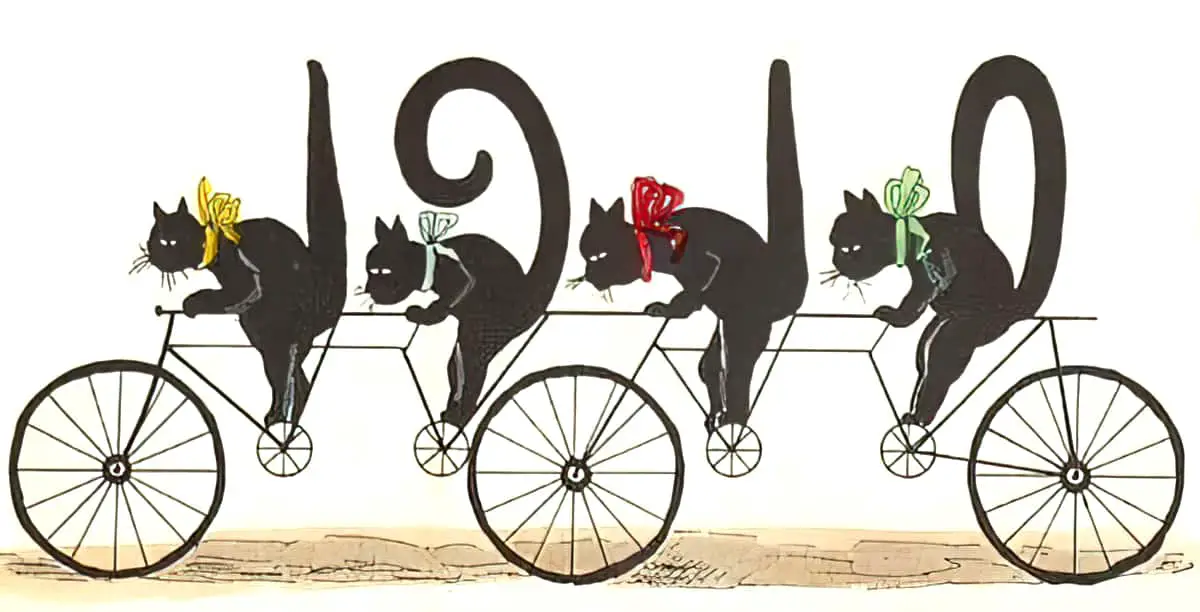

The cat below is from the 1970s, but harks back to an earlier age of cat illustration.

Evgueny Charushin, Russian for ‘Little Sparrow’, 1974

Not all of Wain’s cats were as creepy as those ones. The cat below is a little cuter, in my opinion. The flowers help. The fact that it’s not staring at me also helps. What doesn’t help: the cat version of sanpaku.

Sanpaku (“three white”) is a Japanese word and describes eyes in which the iris shows white at the bottom. A few people have eyes which are naturally sanpaku. Like the hooked nose and widow’s peak hairline, sanpaku has become associated with villainy.

From celebrity world, Audrina Patridge from reality TV show The Hills has pretty consistent sanpaku, which gives her a villainous look although she’s not a villainous character.

It wasn’t just Louis Wain drawing cats’ eyes like this during the early part of the 20th century. The postcard below has a Louis Wain vibe to it. Actual cats don’t show the ‘whites’ of their eyes — cat eyes work very differently from ours. Their iris fills what their pupil does not. When the artist decides to repurpose the cat iris for a humanesque white, they are giving their cat a Louis Wain vibe.

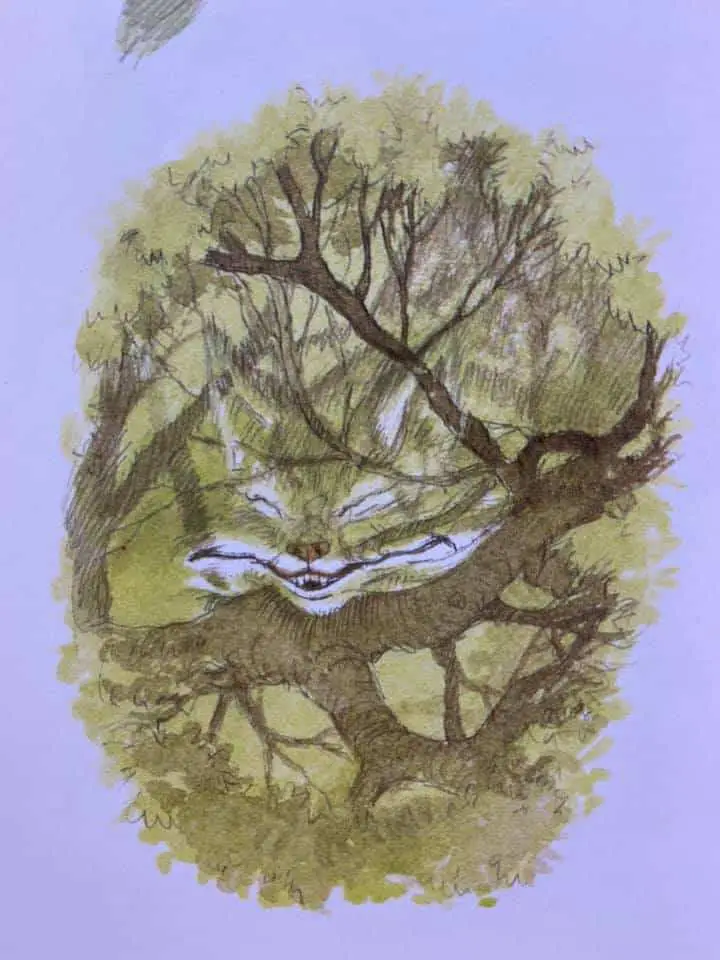

THE CREEPY SMILING CAT

As a little kid I had a stuffed cat which was basically flat in shape. Its sad little mouth had been sewn on, and this cat disturbed me because no matter how I played with it, it always looked sad. If you look at a cat from the front, it looks sad. But if you look at a cat from the side, it’s got a permanent ‘smile’.

This may contribute to the two-faced Janus associations we humans have developed for cats.

Cats aside, there is a long history of horror smiles in art and storytelling. The creepy smile is often associated not with cats but with clowns. Commentators speculate that the smile is multivalent because it is associated with the rictus of pain (especially the pain of childbirth, which is harrowing).

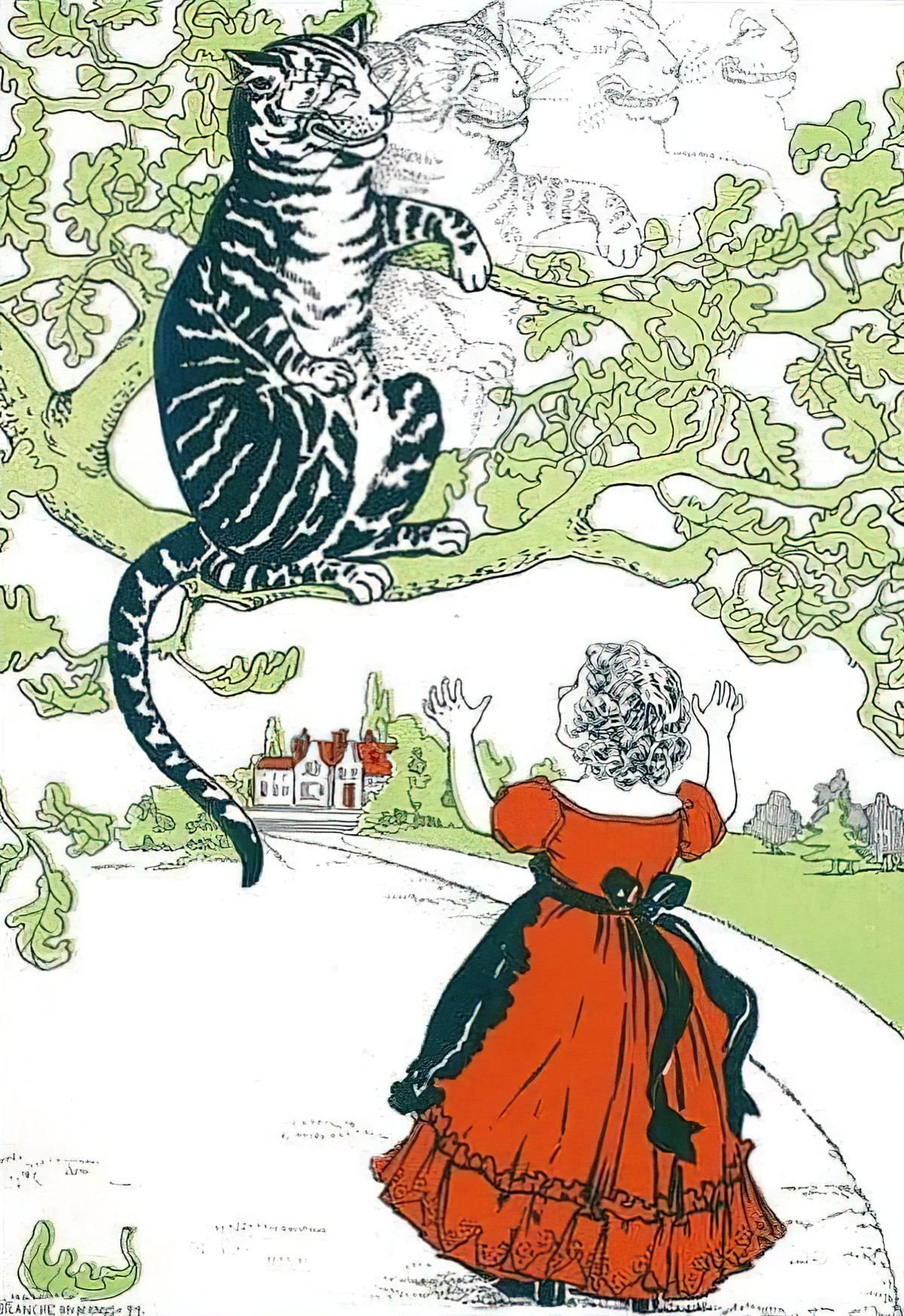

Until I read the description of the picture below, I thought I was looking at the famous Cheshire Cat created by Lewis Carroll. No, but Carroll’s Cheshire Cat has clearly been influential on subequent cat characterisations.

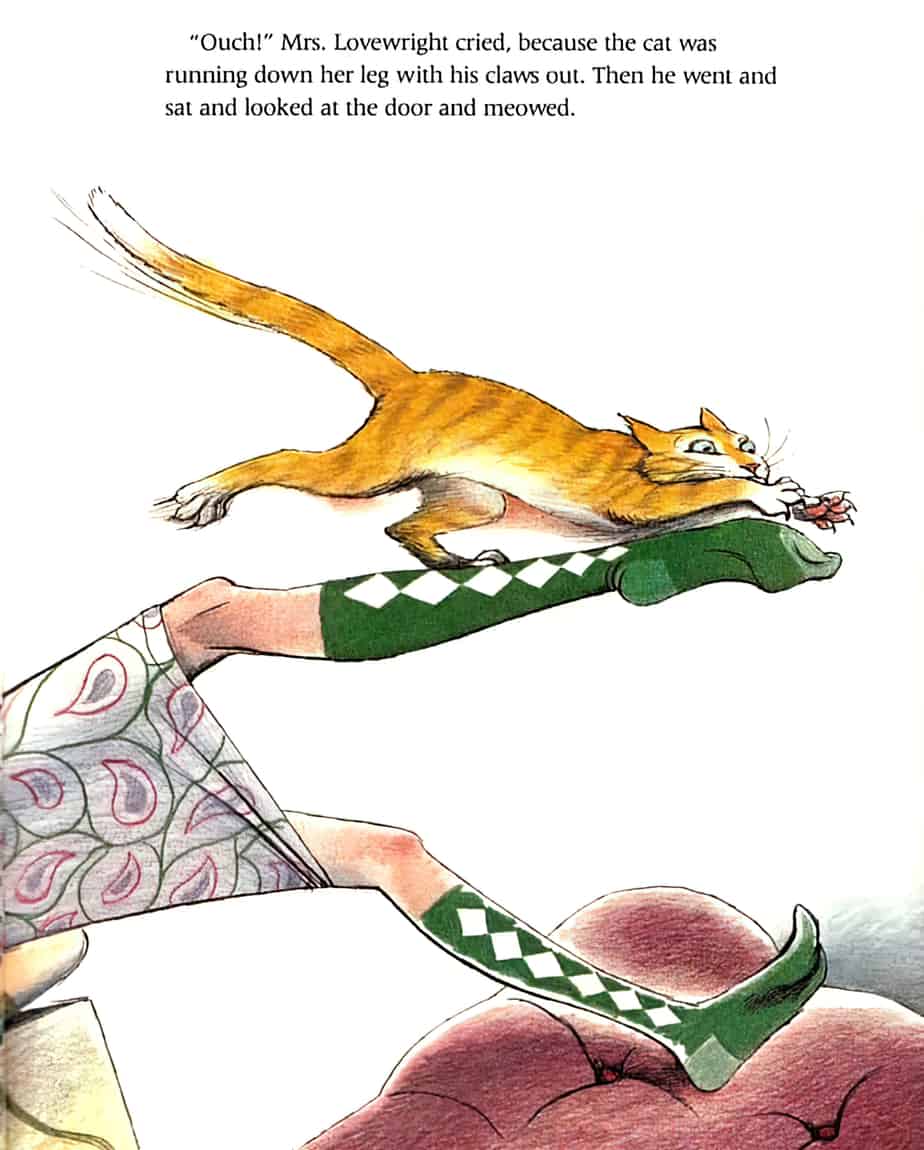

CATS AND THEIR CLAWS

Illustrator Edward Gorey is well-known for his art and also well-known for his house full of cats. He loved his cats and afforded them complete free will inside his apartment. His love for cats comes across in his work, though the illustration below makes me think the woman is about to get scratched up.

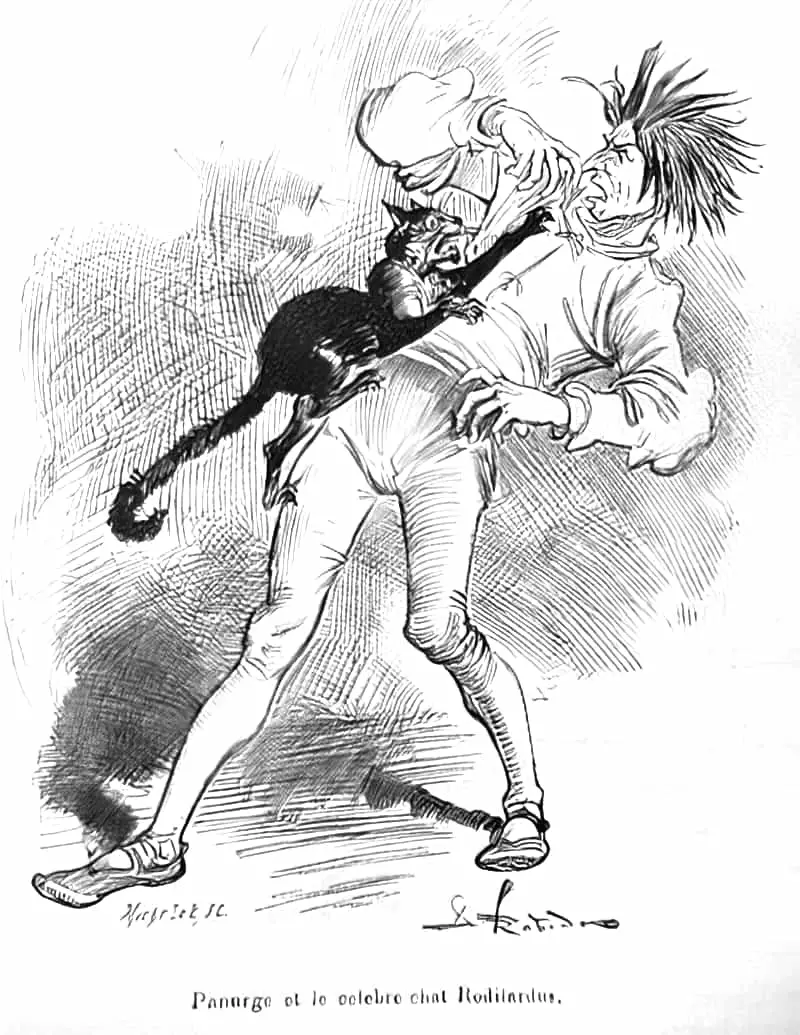

FAUSTIAN ASSOCIATIONS

In James Joyce’s The Cat and the Devil (1957), the cat seemingly plays a minor role. Yet on closer consideration, the story appears a parodic play with the Faust myth, where a cat rather than a woman is presented as sacrificial; besides the cat’s action is not voluntary and therefore less sublime. The Devil claims “the first person who crosses the bridge”, but, as in many folktales, he is outwitted. Had he said “the first human being”, the Lord Mayor would have to offer him one of his subjects. Instead, the cunning man sends a cat across the bridge, which presumably makes no difference, as cats are supposed to have no souls and thus have nothing to fear from the Devil. In the 1980 edition of the book, illustrated by Roger Blachon, the last doublespread shows the cat joyfully playing with the tip of the Devil’s tail, much to the latter’s annoyance. Yet the story certainly accentuates the association between the Devil and the cat, even though Blachon chooses to depict the cat white rather than black.

Maria Nikolajeva, Power, Voice and Subjectivity in Literature for Young Readers

The Man Who Disliked Cats by P.G. Wodehouse

Header illustration: Cat Hater’s Handbook (1963)